Abstract

In recent decades, outpatient commitment orders have been increasingly used in the follow-up of persons with serious mental disorders. Most studies on outpatient commitment orders have focused on compliance and consumption of health care services; there is little research on the content of outpatient commitment orders from a patient perspective. The aim of this study is to examine patients’ experiences of living with outpatient commitment orders, and is based on qualitative interviews with 16 persons in two Norwegian counties. The data were analysed using a constructivist, interpretive approach to the grounded theory method. The main finding was that patients with outpatient commitment orders felt that their lives were on hold. The feeling of being seen only as patients prevented them from taking responsibility for their own lives. The medical context was perceived as an obstacle to recovery and transition to a more normal life. Patients’ daily lives were dominated by the agenda set by health care providers and many said they were subjected to control measures that resulted in a reduced quality of life. However, informants also spoke of positive experiences as outpatient commitment order patients, such as feeling safe and secure and having easy access to health care staff and services.

In recent decades, outpatient commitment (OC) orders have been introduced in an increasing number of jurisdictions worldwide (Rugkåsa, 2011). OC orders are legal regimes that give clinicians the authority to supervise patients discharged from mental hospitals. The core elements are medication and clinical judgment calls (O'Reilly, Dawson, & Burns, 2012). The content and criteria of national laws vary with regard to coercive powers and the criteria for imposing OC (Høyer & Ferris, 2001). Common to all schemes is that discharged patients who still need treatment will receive it even if it is not voluntary. OC is intended to be an alternative to compulsory hospitalization, giving patients greater freedom while maintaining their mental stability with continued treatment. The use of OC is increasing, despite a lack of certain knowledge about the effect of coercion in mental health treatment (Høyer, 2009). Proponents argue that OC reduces the need for hospitalization, facilitates patient follow-up, and is less restrictive than hospitalization. Critics argue that OC threatens basic human rights by stigmatizing and preventing people from living their lives as they wish (Sjostrom, Zetterberg, & Markstrom, 2011). Different uses of OC in different countries have led to the criticism that the scheme is based more on the various needs of social control than the patients’ actual treatment needs (Burns & Dawson, 2009).

In Norway, a compulsory mental health care order is subject to the same regulations for both in- and outpatients (Psykisk helsevernloven [Norwegian Mental Health Act], 1990). One stipulation is that the patient has a place to live. OC requires that patients who do not show up for their treatment appointments can be forced to come. If a patient refuses treatment, a separate compulsory treatment decision is necessary. Re-hospitalization from OC requires a simple procedure: the clinician responsible for the patient can readmit the patient without the need for any new independent assessment. The extent of OC in Norway is unclear, but existing data suggest an increase in its use (Bremnes, Hatling, & Bjørngaard, 2008). Estimates suggest that about one-third of the decisions on compulsory inpatient admissions are followed by an OC decision (Bremnes, Pedersen, & Hellevik, 2010).

There are an increasing number of quantitative studies examining the consumption of health care for patients under OC (Burns et al., 2013). Systematic literature reviews conclude that there is no scientific evidence for claiming that OC reduces health care consumption or improves patients’ treatment compliance (Churchill, Owen, Singh, & Hotopf, 2007; Maughan, Molodynski, Rugkasa, & Burns, 2013). There is less research on the content of OC from a patient perspective. The relatively few qualitative studies point in different directions. A study by Sjöström (2012) shows that many patients feel they lack knowledge of the scheme. Other studies show that patients experience greater autonomy and appreciate the structure, support, and follow-up, but experience little influence on their treatment, reduced choices in housing, and restrictions on travel (Gibbs, Dawson, Ansley, & Mullen, 2005; O'Reilly, Keegan, Corring, Shrikhande, & Natarajan, 2006; Ridley & Hunter, 2013). Riley, Høyer, and Lorem (2014) showed that patients feel that their freedom is restricted, and that they only agree to OC because they consider it better than compulsory hospitalization. Both Gault, Gallagher, and Chambers (2013) and Hughes, Hayward, and Finlay (2009) found that a caring, supportive relationship reduced patients’ feeling of coercion under OC.

Further studies are needed to improve the knowledge base for an overall understanding of OC. The aim of this study was to examine patients’ experiences of living with OC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a qualitative interview study with a constructivist, interpretive approach to the grounded theory method (Charmaz, 2006). Living with an OC order affects patients’ self-understanding and, thereby, their relationships to others. Grounded theory method was selected because it examines the relationship between individuals and their social environment in an interactional perspective.

Recruitment and Setting

The study was conducted in two counties in Eastern Norway with a population of 383,000. The sampling was selective and aimed to achieve a variety of characteristics expected to reflect patients’ experiences of living with OC. Inclusion criteria were being under an OC order, having at least six months’ experience of OC, living in one of the counties, being 18–67 years of age, speaking Norwegian, and being competent to provide consent. The initial recruitment was based on a survey from the hospitals showing that 33 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The number on OC varied during the interview period as new patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria and others discontinued the OC. During the period December 2012 to October 2013, 16 participants were recruited. Additional interviews, after the sixteenth, were not conducted as our experience was that the last interviews confirmed previous themes and did not provide new perspectives. The invitation to participate was given by the psychiatrist treating the patients. No explanation was required from those who refused to participate, but several mentioned the uncertainty of the interview situation and further use of the material.

Participants

The sample consisted of eight women and eight men. The age range was 26–66 with a median of 43 years. All patients lived alone in a flat with practical assistance and support from social services and staff provided by the local municipality. Six of the flats were part of a council care home with 24-hour staffing. There were fixed agreements for contact with health care professionals, while the care home residents had access to clinicians beyond the agreements. All patients had some contact with their families, but with varying frequency and content. Twelve patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia, three with affective disorder, and one with another psychotic disorder. The duration of their contact with mental health services varied from 3 to 26 years, with a median of 11.5 years. Nine participants had less than one year's experience of OC, three between one and four years, and four participants had over four years of OC experience. Five patients reported previous, and four current, periods of substance abuse. Four of the previous substance abusers had regular, mandatory, urine tests. All participants were receiving social welfare benefits. Five were engaged in educational or work-related activities, while another five had regular leisure activities.

Data Collection

The data collection consisted of one interview with each of the 16 participants. The interviews started by asking the participant to share his or her experience of living with OC. The patient's story was followed by more specific questions from the researcher to elaborate on key topics related to OC. The collection and analysis of data was carried out in a parallel process where each interview was coded and analysed before the next took place. The first interview used a theme-based interview guide, based on the research team's pre-understandings and on a pilot interview with a client representative with experience of OC. In later interviews, this guide was modified based on the interpretation of the findings. In this way emerging themes were illuminated in subsequent interviews. Fourteen of the interviews took place in the participants’ flats, and two were conducted in the hospital. All interviews were conducted by the first author and lasted from 35 to 70 minutes. Thirteen participants consented to digital recording. Each interview was transcribed verbatim; notes were taken during the unrecorded interviews, and are available on request.

Analysis

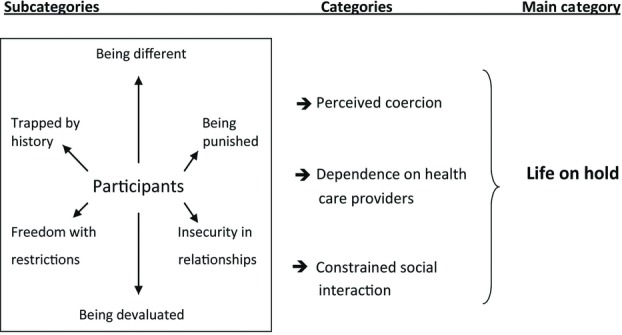

The analysis was performed in steps, using initial, focused, and theoretical coding as described by Charmaz (2006). The participants’ experiences, coping strategies, and consequences of selected strategies were emphasized (Creswell, 2013). The initial coding identified meaning units in the transcribed text. The most important and most frequent codes were used to identify key trends in the material (focused coding). The theoretical coding examined patterns and relationships as well as the hierarchy between the categories. Figure 1 shows that the analysis led to six subcategories. These subcategories describe different experiences of living with OC that affected the participants’ relationships to others leading to the development of the main category (Glaser, 1978).

FIGURE 1. .

Patients subjected to OC experience that the scheme affects them in different ways. These experiences affects relationship with others and lead to the feeling that life is on hold.

In the analysis, the categories were continuously assessed in light of the interview material to ensure a good grounding in the data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The development of categories was performed manually. The interview data were then sorted into categories using NVivo 10 (Alfasoft, Sweden) to ensure that the categories covered the content of the material.

Ethical Considerations

The participants were informed verbally and in writing about the study before signing a written consent form. They were told that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw consent at any time without therapeutic consequences. The information emphasized that the interview was for research, not clinical, purposes. It was considered that there was a small risk of the interviews raising difficult topics, and was therefore agreed that participants could contact a psychiatrist as needed. All data were treated confidentially and stored in de-identified form. No names are used in the presentation. The study was approved by the Data Protection Officer and the guidelines of the World Medical Association (2013) were followed.

RESULTS

Life on Hold

The main study finding, Life on Hold, reflects participants’ perceptions that OC prevented them from taking control of their own lives. The main finding is based on the participants’ experiences of OC according to the categories Perceived Coercion, Dependence on Health Care Providers, and Constrained Social Interactions (Figure 1). The findings are presented in terms of these categories.

Perceived Coercion

A key finding was that participants understood the use of medication as the dominant instrument in OC, and that it would be administered by force if they resisted. The participants felt that their opinions about treatment were not recognized, and that treatment considerations were based solely on diagnosis and medical history:

Yes, it's forced follow-up. I need a Trilafon injection every fortnight because the psychiatrist thinks I have a mental illness. I reckon I don't. I asked the doctor to stop Trilafon, but he wouldn't. So, I'll just have to continue. And then it's forced. (Participant 54)

The participants found that the medications had side effects, such as lethargy, lack of creativity, and reduced happiness. They wanted a reduction in medication to mobilize their own resources. Several accepted the use of medicines in situations they described as crises. Otherwise, they preferred to live without medication even if it meant a risk of relapse. They did not experience a dynamic that linked medication dosages to changes in their symptoms and functioning. Instead, they experienced long-term compulsory medical treatment:

If you go crazy, they can hold you and maybe drug you for a short period. I agree with that. But having the power to say: “No, you have a diagnosis so we must drug you your whole life,” I think that's abuse. It's quite simply evil and stupid to think like that. (Participant 36)

Participants were very concerned about medication, and many questioned whether it had any positive effect on their problems:

No, I wouldn't exactly say the medicines have helped. But I just have to put up with the medicines I get. It's not my choice, I just have to. But I don't have good experience with medicines, because I don't think they work. But they think they do, so I just have to put up with them. (Participant 50)

Seven of the participants were highly critical of OC, six were ambivalent, and three participants were mostly positive. The main issue for most was the lack of collaboration on medication. All perceived being subject to forced medication, however the hospitals’ records showed that only two participants had a current forced medication order. Another seven participants had a previous experience of such a decision. Only two participants related experiences of physical force where the police took them to the hospital. Many more had experienced clinicians threatening to use force or readmission if they opposed the medication:

After 1½ years I was told that either I agree to be medicated or I'll be put in a closed ward and be medicated by force. Then I said, “You'd better put me in a closed ward and force me because I don't agree either way.” (Participant 36)

Many of the participants’ stories revealed that they opposed OC verbally, but complied in practice. This may be due to past experiences:

I haven't resisted because I know if I do, well—I've seen other patients being forced, they're held by their arms and forced to have injections, almost with some violence. The worst thing for me is thinking of the shock I'd get if someone grabbed my arms and held me down. It hasn't happened to me, but I know the forcing exists and I know I couldn't escape it. (Participant 66)

Many participants reported that they were used to close follow-up contact and did not normally think much about OC. Yet, most said that they felt different because they were under an involuntary scheme. The coercion would emerge if they resisted the content of the OC. Several participants felt misunderstood when clinicians lacked contextual understanding or when the participants’ record described events differently from how the participants experienced them. The participants reported different reactions to this; some protested, many adapted. Several felt that they were being punished:

There's one thing I'm waiting for. That's a recommendation for a driving licence. I'm waiting for the doctor to give me that statement and he wants to wait a few months to see if I'm stable. I don't know if I like being under OC, it's a bit too much of a punishment. Like the licence, I feel that's a punishment. I can drive, but I'm not allowed to. (Participant 45)

Dependence on Health Care Providers

Participants’ narratives revealed a dependence on clinicians’ assessments. They experienced a lack of information about the OC order, and were continuously unsure about the borderline between what they could decide themselves and what staff decided. Their uncertainty also included how they had to function in order to get the OC terminated. This gave them a sense of reduced control over their lives:

No, it's never been explained to me. For some periods, I didn't have it [OC], but then they start it, then it finishes, and then it starts again. They've never kind of explained about my illness and medicines. What is it really? (Participant 61)

The participants felt that the psychiatrist had a key role in the decision and implementation of the OC order. Most participants rarely met with the psychiatrist, some only 1–4 times a year. Such infrequent contact provided limited opportunities to discuss OC. The participants wanted to talk about medications and try reduced doses and medication-free periods. Several participants revealed a wish for their general practitioner (GP) to follow-up with the OC order, because GPs were felt to be more open to an ongoing dialogue.

Contact with care providers varied from once a week to several times a day and consisted of talks, practical assistance, and help with developing a social life. The participants believed that staff also were obligated to comply with the OC order and had little authority to make changes. Participants experienced reduced trust in care providers who supported the medical treatment without personal experience of the effects of the medications.

The participants described a world where they felt that staff interpreted their behaviour in terms of a clinical picture, that is, behaviour was assessed according to symptoms of mental illness. Patients felt a lack of appreciation for their lives before the illness and for areas they had mastered. Many acknowledged difficulties, but were less concerned with mental illness and more with everyday functioning. Several described their lives as normal for them, and felt uncertain about their coping ability when others laid the framework for their lives, making it more important to adapt to others’ expectations than to find one's own solutions:

I think they maybe thought I got a bit worse when I came back, so they were very worried. So they told the doctor at the hospital and she gave me an ultimatum. If I forgot the medicines, and they couldn't get hold of me, that would be the last time I could get leave. What worries me a bit is that there can easily be misunderstandings if it's very rigid. What if I'm really trying hard to stick to their rules and something happens beyond my control? (Participant 29)

Similar experiences were found in many participants’ interviews, illustrating how the participants under OC felt controlled and categorized as ill. The experience of coercion and control was, thus, not only linked to specific medication situations, but permeated their whole world. When others define one's scope of action, life becomes tentative. This is essentially a negative experience, but some participants also emphasized the positive aspects OC, such as the feeling of security, protection, and access to help. They found it easier to function in everyday life within a clear framework, without having to make choices.

Constrained Social Interactions

Participants’ narratives indicated the central role of health care providers in their social networks. The participants expressed a desire for contact with other people, but had few close relationships; many felt lonely. The professional network and other patients became a substitute for family and especially friends:

I'd rather be with healthy people, to put it that way. In periods I've been with other people, partied a bit, had fun. But now I haven't got anyone, so then it's OK when the nurse comes. But it doesn't really mean as much as having a good friend. You maybe feel afraid to say private things, but when you're all alone, it's nice if someone comes. (Participant 61)

The contact with care providers is important because the participants had few social relationships. The health professionals were described as a mixture of helpers, friends, and inspectors. Several participants thought they would lose this contact if OC ended. The lack of integration into the local community was revealed through descriptions of everyday life. Activities were mainly organized by staff, and were often linked to the participants’ homes. Even though the participants all found that their living arrangements enabled more freedom compared to inpatient care, they felt that they were expected to open their homes to health care staff. The home is, thus, not just a private arena, but also a venue for the activities of the staff. Participants living in a care home perceived the close contact with staff as negative in relation to living a normal life:

I don't like it here, I really don't. You're just too close to the nursing staff. Yes, it's just too close up; I've been here since May, and I haven't liked it a single day. (Participant 26)

The residential structure means that visitors must also relate to the staff. Some participants compared the care home with previous stays in institutions, and found they were labelled mentally ill because the accommodation was known locally as a psychiatric home.

Several participants referred to their everyday life as consisting of fixed times for talks, medication, and urine tests and restrictions on going where they wanted. They felt locked into a structure with a negative effect on social integration:

My friends are really annoyed with the whole arrangement. I go fishing a lot in the summer. At five o'clock I have to come and take tablets. I can't spend the night anywhere, because at seven a.m. they bring the tablets to my home. Three days a week I have to take a urine test at the doctor's. So everything's split up all the time, I never kind of get a whole day. (Participant 34)

The restrictions were perceived as part of the OC. Some participants with extensive experience of OC seemed to have adapted to the framework and were less concerned about the reduced freedom. Although they said they did not like coercion, their attention was more directed toward mastering their illness:

I think it's OK because you're first in the queue again if you get ill. And you get free medicine and dentist. I think that's great. That's quite all right by me, in practice there's no difference except you get in faster if you're ill. It sounds really weird, compulsory mental health care, but it works OK. (Participant 47)

Other participants, who had been under OC orders for a shorter time, related different experiences:

As for OC, I'm not happy at all. I was supposed to go to a concert on Saturday, but nobody could go with me even though I'd asked three weeks before. And it's been decided that I can't drink light beer, not even non-alcoholic beer. If I'm going to a concert, it's OK to drink non-alcoholic beer, at least. It's like I've done something really bad, so I'm being punished. But I haven't. (Participant 26)

A number of participants discussed becoming defensive when family and friends ask about OC. Participants found OC difficult to explain because it would expose problem areas and reveal to others their lack of autonomy. Several said that they chose to remain silent even though they had experienced that silence could be misinterpreted as a lack of interest. Many experienced a negative focus in society, making it harder to live with their mental disorder:

It says the diagnoses are so bad that I don't even dare mention it. Based on those diagnoses, I'm supposed to be an insane person who can actually attack people and beat them to death and shoot and kill people. That's how bad the diagnoses are. But I'm not that kind of person. (Participant 66)

Media linkage of crimes to mental illness was perceived as stigmatizing. Several believed that others considered them dangerous because they were under OC orders. In everyday life, they lacked someone who unconditionally supported their situation. The health care personnel had their professional point of view. Their families were supportive, but also posed a dilemma in that the participants were uncertain whether their family would support them or the clinicians if and when a choice had to be made. Several participants believed friends or acquaintances would drop them if they found out that they were under OC orders.

DISCUSSION

The main study finding was that OC gave participants the feeling of still being patients because they felt that staff treated them as if they were sick. In the patient role, they were in limbo and dependent on others’ assessments of their psychological difficulties. They could not start to shape their everyday lives using their own resources. They experienced life as on hold. The treatment of severe mental illness is based on pharmacological, psychological, and social approaches (Helsedirektoratet [Norwegian Directorate of Health], 2013). User participation is particularly emphasized and is a statutory right (Pasient-og brukerrettighetsloven [The Patients Rights Act], 1999). Participants in this study experienced that clinicians had a one-sided emphasis on medication. Conrad (2007) shows how problems are often considered in medical terms and described in medical terminology. Health care workers were felt to be experts with an illness focus that prolonged the participants’ dependency and did not allow for independent coping. The participants wanted help, but did not feel that medication solved their problems. This finding is similar to those of Canvin, Bartlett, and Pinfold (2002) and Gault (2009) who found that clinicians were more focused on social control than on a holistic approach for treatment. Patients missed a sympathetic response when clinicians emphasized symptom treatment and social adjustment more than finding out how the patients were really getting on (Eisenberg, 1977). This challenges cooperation, in general, and cooperation regarding medication, in particular (Gault et al., 2013). Foucault (2001) shows how a psychiatric discourse has evolved where medical treatment based on a scientific approach has taken over society's task of treating the mentally ill. Psychiatry has thus taken on a societal role of social control of people who appear irrational (Roberts, 2005). Such a model alienates patients from their problems and hands responsibility for treatment to health professionals. Patients are disciplined into a social role where they are expected to act according to society's expectations (Foucault, 1995). The present study illustrates how this takes place for OC patients.

Coercive treatment is formally linked to provisions of mental health legislation, but also will take place informally through the practices developed (Hatling, 2013). Participants’ narratives contained little formal coercion. More common was the feeling of being subjected to informal coercion, where clinicians had the power and where deviations were met by threats of coercive measures or hospitalization. OC practice seems to have evolved toward control of more aspects of life than permitted in formal legislation (Vatne, 2006). This occurs when patients are subject to control regimes, excluded from discussions, and lack information on how the scheme works. The lack of understanding of OC creates a grey area between free choice and coercion that health professionals should, but often do not, unambiguously explain. Patients thus comply with OC orders because they are uncertain about the terms. These results also were found in studies by Stroud, Doughty, and Banks (2013) and Sjöström (2012), and were supported by Brophy and Ring (2004) who showed that OC patients lack knowledge of the purpose of the scheme and their rights. Ridley and Hunter (2013) showed that patients are listened to, but participate little in decisions, particularly in relation to medication.

OC patients’ relationships with health professionals is important because, for many patients, it constitutes most of their social network. However, the dependency on a professional network hinders social contact with others (Eriksson & Hummelvoll, 2012). The mental disorder may affect people's social identity and deter social participation. This is reinforced by a lack of employment (Davis & Rinaldi, 2004). The study participants experienced checks and controls that impeded social interaction. When their homes were also a venue for treatment, they had nothing left to call their own. Everyone needs a place where he or she can set limits and interact with others on his or her own terms. Lack of privacy thus hinders social integration (Allen, 2003).

These participants found that OC limited their natural interaction with society, just as in the study by Gibbs, Dawson, Ansley, and Mullen (2005). O'Reilly et al. (2006) found that patients felt that OC lasted too long and were worried about the side effects of medications. Yet, both studies showed that most patients were positive about their OC order, because the OC structure allowed them to develop. Riley et al. (2014) found that patients adapted to OC even though they did not want the scheme. In the studies by Gibbs et al. (2005), O'Reilly et al. (2006), and Riley et al. (2014), patients compared OC to previous compulsory hospitalization and thus experienced greater autonomy. In the present study, most of the participants were negative about being on an OC order. They compared everyday life under OC with an independent life in society. From this perspective, they experienced reduced autonomy and faced obstacles to using their own resources, resulting in a lack of control over their lives. They felt devalued and different. Drevdahl (2002) showed how this can lead to individuals being marginalized in society.

Participants in this study saw OC as a barrier to their recovery. They felt stuck in a patient role with little genuine participation. A recovery-oriented practice focuses on individuals’ experiences of what helps and how they can benefit from these experiences (Anthony, 1993). Recovery is both a personal and social process where patients work on improvement, based on their own resources. Environment and social conditions are important. If OC is to aim at patients’ recovery, it must acknowledge patients’ experiences and base its approach on each individual's functioning. A medical approach may be included, but recovery has a broader perspective, embracing self-understanding and social interaction (Borg, Karlsson, & Stenhammer, 2013). Hughes et al. (2009) found that OC inhibited patients’ recovery and emphasized particularly negative experiences with medication. This supports the findings of the present study, emphasizing that OC should be understood in light of how it is experienced in practice and not merely in relation to the intentions of the legislation. The content and practice of OC must be better adjusted to patients’ overall needs. The present study suggests that improved information, especially regarding medical treatment, is needed. The participants are basically neither for nor against medication, but need information about advantages, disadvantages, and treatment alternatives and to have their experiences count in the decision-making process. This finding is supported by Lorem, Frafjord, Steffensen, and Wang (2014) and indicates a need for more dialogue around various alternatives in the follow-up phase. Respect and user participation decrease patients’ feelings of coercion and improve treatment cooperation (Gault, 2009). Clinicians should, therefore, aim for fair, inclusive, and individualized treatment (Galon & Wineman, 2010). OC should enhance coping, self-understanding, and everyday functioning despite the limitations imposed by the mental disorder (Davidson & Roe, 2007). The present study indicates that patients’ mere adaptation to the treatment must be replaced by patient-clinician cooperation on treatment alternatives.

Limitations

This study was conducted in a limited geographical area. There is a risk that the study has captured a local practice that differs from the totality. A characteristic of grounded theory is to follow previous themes in later interviews, therefore, shared experiences from the first participants may have affected subsequent interviews. In the sample, a majority of the participants were critical of the use of OC. Those with negative experiences may have been more willing to communicate their experiences than those with positive experiences. Negative patients may experience fewer symptoms and find OC more constraining. The inclusion criteria of patients having the capacity to consent may have excluded the most seriously ill patients who receive the greatest benefit from OC. The interviews reveal the participants’ subjective assessments of their own lives. Further interviews might have provided additional perspectives. Nevertheless, our experience was that the later interviews confirmed previous themes and did not provide new perspectives. The objective of the study was not to generalize, but to use a qualitative approach to describe key experiences in OC patients’ lives (Creswell, 2013). The findings are supported by other studies, suggesting validity beyond the participants in the present study.

Conclusion and Clinical Implications

The main finding in this study was that patients with OC orders experienced their lives as being on hold. Their understanding was that OC kept them in a role as patients and made them hesitant and dependent on health professionals’ decisions. The medical context was perceived as an obstacle both to recovery and to a transition to a more normal life. Few patients had experienced concrete physical coercion, but all felt subject to a coercive regime. Inadequate information and poor understanding of the boundary between personal autonomy and clinical decisions gave patients a sense of lacking control over their own lives. The feeling of coercion was, thus, not only linked to specific situations but it also coloured their whole world. This prevented the patients from developing normal relations with friends and civil society. Despite the very limited coercive powers of OC orders and their infrequent application in practice, all patients reported a high level of perceived coercion in their daily lives as OC patients. Clinicians involved in OC procedures and implementation need to be aware of this phenomenon so they can enhance the autonomy of patients with OC orders.

Declaration of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. The study was funded by the ExtraFoundation for Health and Rehabilitation, Innlandet Hospital Trust and the Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Concurrent Substance Abuse and Mental Health Disorders.

REFERENCES

- Allen M. Waking Rip van Winkle: Why developments in the last 20 years should teach the mental health system not to use housing as a tool of coercion. Behavioral Sciences and the Law. 2003;(4):503–521. doi: 10.1002/bsl.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony W. A. The decade of recovery. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal. 1993;(4):1. [Google Scholar]

- Borg M., Karlsson B., Stenhammer A. Trondheim, Norway: NAPHA, Nasjonalt Kompetansesenter for Psykisk Helsearbeid; 2013. Recoveryorienterte praksiser: En systematisk kunnskapssammenstilling [Recovery oriented practices: A systematic knowledge compilation] Vol. nr. 4/2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bremnes R., Hatling T., Bjørngaard J. H. SINTEF rapport A8237 (SINTEF. Helse. Helsetjenesteforskning: trykt utg. Oslo, Norway: SINTEF Helse; 2008. Bruk av tvungent psykisk helsevern uten døgnomsorg i 2007. Bruk av legemidler uten samtykke utenfor institusjon i 2007 [The use of involuntary psychiatric outpatient care in 2007. The use of medication without consent outside institutions in 2007] pp. 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bremnes R., Pedersen P. B., Hellevik V. Oslo, Norway: Helsedirektoratet; 2010. Bruk av tvang i psykisk helsevern for voksne 2009 [The use of coercion in mental health care for adults in 2009] Rapport (IS-1861) [Google Scholar]

- Brophy L., Ring D. The efficacy of involuntary treatment in the community: Consumer and service provider perspectives. Social Work in Mental Health. 2004;(2/3):157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Burns T., Dawson J. Community treatment orders: How ethical without experimental evidence. Psychological Medicine. 2009;(10):1583–1586. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T., Rugkasa J., Molodynski A., Dawson J., Yeeles K., Vazquez-Montes M. Priebe S. Community treatment orders for patients with psychosis (OCTET): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013:1627–1633. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canvin K., Bartlett A., Pinfold V. A “bittersweet pill to swallow”: Learning from mental health service users’ responses to compulsory community care in England. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2002;(5):361–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2002.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London, UK: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill R., Owen G., Singh S., Hotopf M. International experiences of using community treatment orders. London, UK: Institute of Psychiatry, Kings College London; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad P. The medicalization of society: On the transformation of human conditions into treatable disorders. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L., Roe D. Recovery from versus recovery in serious mental illness: One strategy for lessening confusion plaguing recovery. Journal of Mental Health. 2007;(4):459–470. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M., Rinaldi M. Using an evidence-based approach to enable people with mental health problems to gain and retain employment, education and voluntary work. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;(7):319–322. [Google Scholar]

- Drevdahl D. J. Home and border: The contradictions of community. Advances in Nursing Science. 2002:8–20. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg L. Disease and illness: Distinctions between professional and popular ideas of sickness. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 1977;(1):9–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00114808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson B. G., Hummelvoll J. K. To live as mentally disabled in the risk society. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2012;(7):594–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York, NY: Vintage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M. Madness and civilization: A history of insanity in the age of reason. London, UK: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Galon P. A., Wineman N. M. Coercion and procedural justice in psychiatric care: State of the science and implications for nursing. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2010;(5):307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gault I. Service-user and carer perspectives on compliance and compulsory treatment in community mental health services. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2009;(5):504–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gault I., Gallagher A., Chambers M. Perspectives on medicine adherence in service users and carers with experience of legally sanctioned detention and medication: A qualitative study. Patient Preference and Adherence. 2013:787–799. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S44894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs A., Dawson J., Ansley C., Mullen R. How patients in New Zealand view community treatment orders. Journal of Mental Health. 2005;(4):357–368. doi: 10.1080/09638230500229541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G. Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G., Strauss A. L. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hatling T. Bruk av tvang i psykiske helsetjenester [The use of coercion in mental health care] In: Norvoll R., editor. Samfunn og psykisk helse: Samfunnsvitenskapelige perspektiver [Society and mental health: Social science perspectives]. Oslo, Norway: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2013. pp. 243–284. [Google Scholar]

- Helsedirektoratet [Norwegian Directorate of Health]. Utredning, behandling og oppfølging av personer med psykoselidelser. Nasjonale faglige retningslinjer. Oslo, Norway: Author; 2013. [Assessment, treatment and monitoring of people with psychotic disorders. National guidelines]. (IS-1957) [Google Scholar]

- Høyer G. Kunnskapsgrunnlaget i forhold til bruk av tvang i det psykiske helsevern. Vurdering av behandlingsvilkåret i psykisk helsevernloven. Oslo, Norway: Helsedirektoratet; 2009. [The knowledge base in relation to the use of coercion in mental health care. Assessment of the treatment condition in the Mental Health Act] (IS-1370) [Google Scholar]

- Høyer G., Ferris R. J. Outpatient commitment. Some reflections on ideology, practice and implications for research. Journal of Mental Health Law. 2001:56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R., Hayward M., Finlay W. M. L. Patients’ perceptions of the impact of involuntary inpatient care on self, relationships, and recovery. Journal of Mental Health. 2009;(2):152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Lorem G. F., Frafjord J. S., Steffensen M., Wang C. E. Medication and participation: A qualitative study of patient experiences with antipsychotic drugs. Nursing Ethics. 2014:347–358. doi: 10.1177/0969733013498528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan D., Molodynski A., Rugkasa J., Burns T. A systematic review of the effect of community treatment orders on service use. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2013:651–663. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0781-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly R., Dawson J., Burns T. Best practices: Best practices in the use of involuntary outpatient treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2012;(5):421–423. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.20120p421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly R. L., Keegan D. L., Corring D., Shrikhande S., Natarajan D. A qualitative analysis of the use of community treatment orders in Saskatchewan. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2006;(6):516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasient-og brukerrettighetsloven [The Patient Rights Act]. Pasient-og brukerrettigheter. 1999, July Retrieved from http: //lovdata.no/dokument/ NL/lov/1999-07-02-63?q=pasientrettighetsloven. [Google Scholar]

- Psykisk helsevernloven [The Mental Health Act] Psykisk helsevern. 1999, July Retrieved from http: //lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1999-07-02-62?q=psykisk+helsevern. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley J., Hunter S. Subjective experiences of compulsory treatment from a qualitative study of early implementation of the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2013:509–518. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley H., Høyer G., Lorem G. F. When coercion moves into your home”—A qualitative study of patient experiences with outpatient commitment in Norway. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2014 doi: 10.1111/hsc.12107. Epub 2014 Apr 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M. The production of the psychiatric subject: Power, knowledge and Michel Foucault. Nursing Philosophy. 2005;(1):33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-769X.2004.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugkåsa J. Compulsion in the community. An overview of legal regimes and current evidence. Impuls Tidsskrift for Psykologi. 2011:56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström S. Stockholm, Sweden: Socialstyrelsen; 2012. Det diffusa tvånget—Patienters upplevelser av öppen tvångsvård [Diffuse coercion. Patient experiences of open coercive care] Socialstyrelsen 2012; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrom S., Zetterberg L., Markstrom U. Why community compulsion became the solution—Reforming mental health law in Sweden. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 2011;(6):419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud J., Doughty K., Banks L. An exploration of service user and practitioner experiences of community treatment orders. London, UK: National Institute for Health Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vatne S. Oslo, Sweden: Gyldendal Akademisk; 2006. Korrigere og anerkjenne: relasjonens betydning i miljøterapi [To correct and to acknowledge. The importance of relationships in milieu therapy] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. Retrieved from http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]