Interviews with 26 DRSs identified barriers to the development of an effective system for older driver evaluations.

MeSH TERMS: age factors; automobile driving; geriatric assessment; health knowledge, attitudes, practice; rehabilitation

Abstract

OBJECTIVE. We explored driving rehabilitation specialists’ (DRSs’) perspectives on older driver evaluations.

METHOD. We conducted interviews with 26 DRSs across the United States who evaluate older drivers. Transcript analysis followed general inductive techniques to identify themes related to current systems and barriers to use.

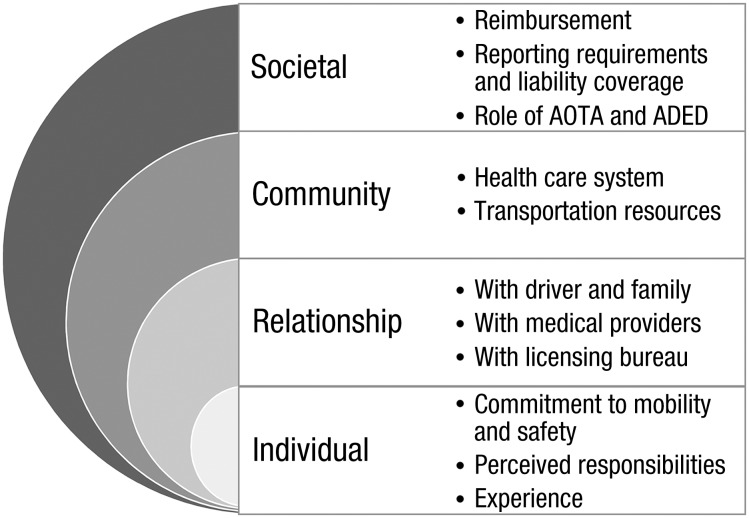

RESULTS. Themes, by Social–Ecological Model level, were as follows: (1) individual occupational therapists’ commitment to mobility and safety, perceived responsibilities, and experience; (2) DRSs’ relationships with drivers, medical providers, and licensing bureaus; (3) the community surrounding the DRSs, including the health care system and transportation resources; and (4) societal factors, including DRS reimbursement, reporting requirements and liability coverage, and role of national organizations.

CONCLUSIONS. This qualitative study identified barriers to the development of an effective system for older driver evaluations. Future work should verify, refine, and expand these findings by targeting other stakeholder groups.

Occupational therapists, especially those with advanced training, have the knowledge and skills to understand progressive conditions and aging-associated changes that affect driving. Indeed, driving rehabilitation specialists (DRSs)—most of whom are occupational therapists (Dickerson, 2013)—have been recognized as the experts best equipped to evaluate older adults’ driving ability.

A comprehensive driving evaluation commonly includes both off-road clinical and on-road behind-the-wheel portions (Dickerson, 2013; Korner-Bitensky, Toal-Sullivan, & Von Zweck, 2007). Driving rehabilitation programs (DRPs) generally offer both driving skills assessments and training in adaptive driving equipment, but wide variability exists, and efforts have been made to standardize practices (Dickerson & Schold Davis, 2014). In a national survey of DRSs regarding older drivers’ use of their services, Betz et al. (2014) identified issues that included cost of and reimbursement for evaluations, the DRS workforce, and awareness of program availability and benefits.

We used qualitative methods to more deeply explore DRSs’ perspectives on older driver evaluations, including current systems and barriers to and facilitators of use. A better understanding of the issues facing DRSs should allow stakeholders to take action to improve current systems and thereby better support older adults’ health and safe mobility.

Method

Eligible participants were English-speaking evaluators in the publicly available databases of the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA; 2013) or the Association for Driver Rehabilitation Specialists (ADED; 2013) who reported that they provided evaluations to older drivers. Initial invitation emails were sent to evaluators who had completed our previous survey on this topic (Betz et al., 2014). We also used snowball sampling to target evaluators identified by participants as having leadership positions or unique views. Recruitment ended when no new themes emerged (Creswell, 2013).

Following a qualitative descriptive study design (Sandelowski, 2010), we used semistructured interviews to explore barriers to and facilitators of older adults’ use of DRPs. All interviews followed a guide with open-ended questions (Figure 1), lasted 45–60 min, and were conducted by author Betz from February to June 2014. The guide was developed from previous research findings; after it was pilot tested in three interviews, we further refined the questions and flow on the basis of feedback. We also modified the approach to discuss emergent findings with later interviewees. All participants completed the interview. One interview was in person at the evaluator’s office, and the remainder were conducted by telephone. Sessions were recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist. Participants received $15 gift cards; the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Figure 1.

Interview topics.

Within a framework of applied thematic analysis (Guest, MacQueen, & Namey, 2012), we used team-based deductive and inductive techniques. Analyzed material included transcripts (499 pages) and field notes (40 pages). We followed a multistep approach suggested by Thomas (2006) to move from the micro level (text data) to the macro level (data interpretation): After team discussions about initial text review, authors Flaten and Belmashkan independently performed line-by-line readings for pertinent text segments, supported by Atlas.ti (Version 7.1.5; Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany), with 95% consensus.

Our multidisciplinary, experienced analysis team (authors Jones, Flaten, Belmashkan, and Betz) developed a codebook through an iterative, team-consensus approach (Creswell, 2013; Thomas, 2006). We then identified core themes arising from the final set of codes and, in a second level of deductive analysis to enhance our inductive analysis, applied the Social–Ecological Model (SEM; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013) to the codes and initial themes to examine factors at all four system levels (individual, relationship, community, and societal). The SEM is a common framework that describes person–context interaction at different levels of a system, including the bidirectional influence across and between levels. Using our iterative approach, we checked findings in subsequent interviews and through short research presentations to groups of DRSs and generalist occupational therapists.

Results

We interviewed 26 evaluators in 16 states across all regions of the United States (Table 1). Emergent themes, organized according to the SEM, and subthemes were (1) individual occupational therapists’ commitment to mobility and safety, perceived responsibilities, and experience; (2) occupational therapists’ relationships with drivers, medical providers, and licensing bureaus; (3) the community surrounding the DRS, including the larger health care system and available transportation resources; and (4) societal factors, including DRP reimbursement, reporting requirements and liability coverage, and the role of AOTA and ADED (Figure 2). Table 2 provides representative quotes arranged according to SEM level and current and ideal states of practice.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 26)

| Characteristic | Mean (Range) or n (%) |

| Age, yr | 49 (26–67) |

| Time working as driver evaluator, yr | 15 (2–30) |

| Female | 25 (96) |

| U.S. Census region | |

| Northeast | 5 (19.2) |

| Midwest | 8 (30.8) |

| South | 6 (23.1) |

| West | 7 (26.9) |

| Type of practice | |

| Private practice | 6 (23.1) |

| VA hospital | 1 (3.8) |

| Non-VA health care facility | 19 (73.1) |

| Professional background | |

| Occupational therapy | 25 (96.2) |

| Psychology | 1 (3.8) |

| Certified driver rehabilitation specialist | 20 (76.9) |

Note. VA = Veterans Affairs.

Figure 2.

Emergent themes, by Social–Ecological Model level.

Note. ADED = Association for Driver Rehabilitation Specialists; AOTA = American Occupational Therapy Association.

Table 2.

Representative Quotes by Social–Ecological Model Level and State of Clinical Practice

| SEM Level | State of Clinical Practice | |

| Current | Ideal | |

| Individual | “It really does take a significant amount [of] more time to be trained. . . . It is frustrating for people, ’cause there is such a need to do this. And we want to grow the amount of OTs in there.” | “It would be nice to not have to spend 1,600 hours to take [the CDRS] exam. I think there should be some way of proving you are ready without needing that many hours.” |

| Relationship | “I give the information to the doctor that I recommend they retire from driving. I give them resources for options.” | “We really need to train physicians and nurse practitioners on what to screen for.” |

| Community | “We don’t have public transportation in certain areas. In most areas. There are no taxis. There are no buses.” | “If we could have some help to coordinate and to put in place some of these [transportation] alternatives, it [might] help the transition go much more successfully.” |

| Societal | “I definitely have concerns about what it looks like from the client’s perspective to have multiple venues of entry into services. Because I think it is confusing. . . . I wish we had a more organized standard of care.” | “In an ideal world . . . there is a ‘best-practice standard.’ That we are held to that standard to be able to provide these services.” |

Note. CDRS = certified driver rehabilitation specialist; OTs = occupational therapists; SEM = Social–Ecological Model.

Individual-Level Factors

A primary finding on the individual level was DRSs’ passion for their work and strong commitment to the well-being of older adults and to community safety: “I feel it is my job to help a person . . . understand why [he or she is] having this problem with driving.” Although most DRSs conducted evaluations at a central site because of logistical concerns, some went to patients’ neighborhood, demonstrating their commitment to individualized attention: “I don’t want them to come to the hospital, where it is a new area for them, because then they don’t do well.”

The second individual-level finding was the variability in perceived professional responsibilities regarding reporting of potentially unsafe drivers. Some DRSs said they did not report clients’ results to the state (“It’s not really my responsibility”) and felt doctors should do it: “The physician knows the patient overall much better [and has] a much more comprehensive and long-term relationship with [the patient].” Other DRSs felt that they, as experts, had a personal responsibility, as well as more familiarity with the reporting process: “I don’t mind reporting, because sometimes I don’t trust . . . that [physicians] will follow through. Sometimes the doctors don’t want to be the bad guys.” Another participant said, “It is my philosophy to report everyone who is unsafe.” Although reporting requirements vary significantly from state to state, it was most typical for DRSs to report to their referral source, including physicians.

Participants expressed concerns over the training required to be an effective and competent evaluator. These concerns included the cost and time to achieve and maintain ADED’s certification (i.e., passing an initial certification exam and then maintaining continuing education credits), which was particularly problematic in areas in which there were low patient volumes, given the required hours of on-the-job training. Many DRSs cited these requirements as a barrier to expanding the pool of qualified DRSs. Most participants said they had stumbled into the field by chance while they were working as a generalist occupational therapist: “The opportunity was there, and I wanted another challenge.” Despite their frustrations with the training process and their own serendipitous histories, most DRSs felt that their work was not ideal for new graduates or people with limited training:

We need to somehow demystify what driver rehab is and make [people] feel like it’s doable. . . . [But driving rehabilitation] is not something that people right out of [occupational therapy] school can do right away. They need time to be able to work at their profession as it is, and learn how to work with people with disabilities and understand the disabilities more thoroughly[, and] then apply that to driver rehab.

Other DRSs echoed the sentiment of encouraging and supporting more professionals to work in driver rehabilitation.

Relationship-Level Factors

Participating DRSs discussed the importance of establishing a good relationship with older drivers and their family members, and they felt that DRSs had important skills and knowledge to help older drivers. The DRSs recognized that many older drivers want objective on-road evidence that they can no longer drive, even if their family or physician already has a high level of concern before any behind-the-wheel evaluation. One DRS remarked, “Once a patient comes to us . . . we have the ability to give them evidence that they are probably looking for, to sometimes help them accept it a little bit better.”

Although DRSs described good relationships and communication with patients, they called for better “collaboration between the licensing physician and the therapist.” Specifically, they spoke of both the need to educate physicians about available driver evaluations and the difficulty of accessing physician groups for education: “Well, the biggest thing I would improve, I would love to get in front of physicians to explain to them what I do on the driving test and that they [physicians] are mandated reporters.”

DRSs were also concerned about poor communication with state licensing bureaus. Although some spoke of being members of state coalitions or working groups with licensing officials, most said that they had little interaction other than when they received referrals or sent back driving reports. One DRS wished for enhanced communication: “being able to [have a] dialogue [with] some of these folks, and sit at the table together.” She continued, linking together both referring providers and licensing bureaus: “Make that a more fluid system . . . a portal that everybody would log in[to], and I could see physicians’ input regarding this issue, as well as the [Department of Motor Vehicles] medical record.”

Community-Level Factors

DRSs worked across the spectrum of settings, ranging from private practices to programs based within a large health care system, and they identified benefits to and drawbacks of the various settings. DRSs in a hospital-based program had access to patients’ electronic medical records; in other cases, doctors’ offices would send a partial medical record so that the DRS would have more background knowledge, but DRSs in private practice felt they did not always receive sufficient information. However, DRSs in private practice recognized that they had greater independence and possibly higher income than DRSs in hospital-based programs. This freedom was tempered by the challenges associated with running a small business, including uncertainty about program sustainability.

Referrals predominantly came from health care providers (“mostly from neurology, then internal medicine and geriatrics”), as well as from licensing bureaus and from individual patients. Regardless of where the referral originated, almost all DRSs said they required a physician’s order:

I will get a call from the older driver or from a family member and then explain to them that insurance doesn’t cover it, but we’re hospital based, so we still require a physician’s order. So they call their physician and have [the physician’s office] fax a script to us.

A recurring community-level theme was the need for transportation resources: “If a person has never used transportation alternatives[,] I may set a homework requirement: ‘Before you come in for the behind-the-wheel evaluation, you should try this.’” Alternative transportation was not limited to buses: “I’ll list family, friends. I’ll give them the option of calling a local college.” The available resources, however, were often seen as inadequate, especially in rural settings.

I deal with farmers. They all live on highways. . . . So I can’t say, well, “You can drive in town, but don’t go on highways.” . . . Plus, there is no assistive transportation out in the country. For those folks, it’s really hard. They have to rely on family and friends and church.

Participants in urban areas also complained about inadequate options: “We have no transportation resources in [southern state]. Except for taxis. . . . If we had better public transportation[,] I wouldn’t feel so guilty about telling somebody they can’t drive.” The issue is not just availability, but also ability; a person who can no longer drive because of cognitive or physical challenges often cannot use public transportation for the same reason.

Societal-Level Factors

A primary finding was concern over inadequate reimbursement for driver evaluations. Most DRSs said they do not pursue reimbursement from insurance companies because they found the claims process too onerous or the reimbursement too low: “I stopped doing [Medicare claims] years ago, because they gave me such a hard time for it, and they wouldn’t pay for the whole assessment.” Most programs were fee for service, and DRSs recognized that the cost may limit both patient evaluations and physician referrals: “We have had physicians say[,] ‘I can’t tell somebody that it is not going to be covered by insurance.’” Given the required equipment and liability coverage for the professional services associated with an evaluation, some DRSs spoke of the difficulty in maintaining programs in the face of poor reimbursement.

DRSs worked under a wide range of state laws related to reporting and liability coverage. In one state, “The onus of responsibility is on the individual [evaluator] to report”; in another, “physicians are mandated reporters, but occupational therapists are not.” In a third state, “it is not mandatory [to report]. The doctors, though . . . can’t be sued.” A fourth state extended liability protection to DRSs: “We are a self-reporting state. . . . we can report with immunity.”

Some DRSs spoke about the relationship between AOTA and ADED. DRSs described AOTA as a bigger organization with legislative abilities and ADED as a lesser known organization that has been “doing a wonderful, super, super job.” As 1 participant said, “Between those two [organizations], we have quite a bit of information and resources . . . coming out that are supported [by] evidence.” However, some DRSs discussed a “tension between ADED and AOTA” stemming from the varied backgrounds of its members. One DRS spoke of “the primary stumbling block”: “AOTA is focused on the generalist occupational therapist and ADED is a multi-disciplinary organization. . . . [ADED] must be very careful not to alienate . . . the nonclinicians within the group.” She felt, however, that the organizations were making steady gains in recognizing the complementary skills of members, including

the expertise of those with traffic safety and driver education backgrounds, because occupational therapists don’t come into this field knowing those two components. And driver educators and traffic safety professionals don’t come into this field knowing the diagnoses and medical side in terms of expertise.

DRSs stressed the “desire to bring the two organizations together, because they are really trying to accomplish the same thing.” Participants also recognized positive changes over the years: “There is more collaboration now between the two organizations.”

Discussion

In qualitative interviews with a sample of DRSs across the country, we identified their passionate commitment to helping older adults but also addressable barriers to the development of an ideal system for older driver evaluations. Exploration of these issues by SEM level identified perceived factors operating at the levels of individual DRSs, their interactions with other stakeholders, their surrounding communities, and the larger sociopolitical realm. To improve the system, it is useful to examine higher level issues that cross all SEM levels: issues related to the DRS workforce, to communication, and to state and national policies.

Ideally, DRSs would be part of a multidisciplinary team (with other health care providers, driving schools, family members, and regulatory agencies), and standardized screening would identify those at-risk older drivers who should be referred for an evaluation (Dickerson & Schold Davis, 2014). In this study, DRSs demonstrated a passionate commitment to their role in helping older adults maintain safe mobility. However, consistent with previous studies (Dickerson, 2013; Yanochko, 2005), workforce issues were a concern. The challenge is supporting the development of more DRSs while recognizing the experience needed for professional competence. To date, occupational therapist training has been “inconsistent and not sufficient” (Stav, 2014, p. 169) to meet growing needs. Recently, AOTA and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration implemented the Gaps and Pathways Project to increase generalist occupational therapists’ role in working with medically at-risk drivers and to strengthen relationships among settings (Lane et al., 2014). Bidirectional collaboration with organizations such as Area Agencies on Aging could also help when counseling older drivers about alternative transportation and driving retirement. Adding to the complexity of the issue is variation in the certification process: States generally require DRSs to be licensed as certified driving instructors; ADED has test-based certification open to multiple specialties; and AOTA has a portfolio-based specialty certification open to occupational therapists. Continued joint leadership by AOTA and ADED has the potential to facilitate further action on these issues.

Enhanced collaboration is an issue from the societal level down to the level of the individual DRS. Marketing or public education campaigns could increase the general public’s awareness of the availability and benefits of driver evaluation services (Betz et al., 2014). Consistent with findings in previous work (Betz et al., 2014; Dickerson, 2013; Korner-Bitensky, Bitensky, Sofer, Man-Son-Hing, & Gelinas, 2006), DRSs said most referrals came from physicians, and participants called for better communication systems (Korner-Bitensky, Menon, von Zweck, & Van Benthem, 2010; Yanochko, 2005). Better medical information would allow DRSs to tailor evaluations, and enhanced reporting systems could improve communication with licensing bureaus and with physicians.

The effect of driving-related policies was a third cross-cutting issue, especially as it related to reporting of unsafe drivers and to reimbursement. Regarding the responsibility to determine driver safety and report unsafe drivers to licensing authorities, DRSs in this study expressed a range of opinions. This variation may stem from differences in state laws concerning mandatory (vs. permissive) reporting and liability coverage for reporters (Korner-Bitensky et al., 2007). In some states, only physicians have liability coverage, yet they often look to occupational therapists for guidance. Given the recognized role of DRSs as experts in determining fitness to drive, states should consider expanding liability coverage to DRSs (Korner-Bitensky et al., 2007).

Appropriate reimbursement for professional driver evaluations has previously been recognized as an important issue (Betz et al., 2014; Yanochko, 2005). DRSs in this study spoke of various strategies, including billing Medicare and adjusting fees to be competitive in local markets. Medicare will reimburse for some services in certain cases (Stressel & Dickerson, 2014), although documentation requirements and low reimbursement levels have made this less attractive to some participants. Our results indicate some misperceptions about reimbursement; in reality, DRSs have successfully been reimbursed by Medicare, worker’s compensation, and state vocational rehabilitation programs (Stressel & Dickerson, 2014). In some states, the Hartford insurance company now reimburses up to $500 for a comprehensive driver evaluation but only after an accident with injury and when the evaluation is ordered by a physician and conducted by an occupational therapist (The Hartford, 2012). Additional avenues for reimbursement could include incentives provided directly to participants (Korner-Bitensky et al., 2010), similar to insurance discounts provided after driver education courses.

Limitations of this study include that the sample was taken from the AOTA and ADED databases, because some DRSs may not be registered. Our study included 26 DRSs located across the United States; as with any qualitative study, generalizability may be limited. Participants were similar in gender, age, and years of experience relative to a previous larger survey of DRSs (Dickerson, 2013), but viewpoints may have varied by these or other factors, such as geographic location. Participation was voluntary with a small incentive, so interviewees may have been particularly passionate about the subject; however, we used snowball sampling to contact additional DRSs identified by participants as having unique or leadership perspectives.

Implications for Occupational Therapy Practice

The results of this study suggest the following areas for action:

Research and policy changes (including continuation of the Gaps and Pathways project) to augment the DRS workforce, particularly through partnerships with general practice occupational therapists and driving schools

Continued efforts to inform and engage practicing DRSs in the Gaps and Pathways project, models of reimbursement, and other aspects of the changing practice landscape

Enhanced communication with and education of other health care providers and the general public

Development and implementation of models for sustainability, including usable strategies for reimbursement.

Conclusion

This qualitative study of a sample of DRSs across the United States revealed both great commitment to older adult safety and also barriers to building an ideal system for older driver assessment. Enhanced education for therapists, health care providers, and the general public, supported by collaboration among national organizations and insurers, has the potential to enhance older driver safety and ease the transition to other forms of transportation. Future research efforts are needed to refine and expand these findings by targeting particular stakeholder groups, including representatives of national organizations and insurers.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Paul Beeson Career Development Award Program (funded by the National Institute on Aging, American Federation for Aging Research, The John A. Hartford Foundation, and The Atlantic Philanthropies; Grant K23AG043123 to Marian E. Betz). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

References

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2013). Find a driving specialist. Retrieved from http://myaota.aota.org/driver_search/index.aspx

- Association for Driver Rehabilitation Specialists. (2013). Member directory. Retrieved from http://www.aded.net/?page=725

- Betz M. E., Dickerson A., Coolman T., Schold Davis E., Jones J., & Schwartz R. (2014). Driving rehabilitation programs for older drivers in the United States. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 28, 306–317. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2014.908336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). The Social–Ecological Model: A framework for prevention. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecologicalmodel.html

- Creswell J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson A. E. (2013). Driving assessment tools used by driver rehabilitation specialists: Survey of use and implications for practice. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67, 564–573. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2013.007823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson A. E., & Schold Davis E. (2014). Driving experts address expanding access through pathways to older driver rehabilitation services: Expert meeting results and implications. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 28, 122–126. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2014.901591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G., MacQueen K. M., & Namey E. E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781483384436 [Google Scholar]

- The Hartford. (2012). Agent eNewsletter: New comprehensive driving evaluation coverage helps drivers. Retrieved from http://pages.agent.thehartford.com/201210_PL_1

- Korner-Bitensky N., Bitensky J., Sofer S., Man-Son-Hing M., & Gelinas I. (2006). Driving evaluation practices of clinicians working in the United States and Canada. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60, 428–434. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.60.4.428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korner-Bitensky N., Menon A., von Zweck C., & Van Benthem K. (2010). A national survey of older driver refresher programs: Practice readiness for a rapidly growing need. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 28, 205–214. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/02703181.2010.491935 [Google Scholar]

- Korner-Bitensky N., Toal-Sullivan D., & Von Zweck C. (2007). Driving and older adults: Towards a national occupational therapy strategy for screening. Occupational Therapy Now, 9(4), 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lane A., Green E., Dickerson A. E., Davis E. S., Rolland B., & Stohler J. T. (2014). Driver rehabilitation programs: Defining program models, services, and expertise. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 28, 177–187. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2014.903582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. (2010). What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing and Health, 33, 77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stav W. B. (2014). Consensus statements on occupational therapy education and professional development related to driving and community mobility. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 28, 169–175. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2014.904536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stressel D., & Dickerson A. E. (2014). Documentation and reimbursable for driver rehabilitation services. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 28, 209–222. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/07380577.2014.904960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27, 237–246. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748 [Google Scholar]

- Yanochko P. (2005). Building a network of convenient, affordable and trustworthy driving assessment and evaluation programs. San Diego, CA: Center for Injury Prevention Policy and Practice, San Diego State University. [Google Scholar]