Abstract

Patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) often develop extrapyramidal signs (EPS), which increase in frequency as the disease progresses. We aimed to investigate the patterns of presentation of EPS in AD and their correlation with clinical and neuropathological features. 4284 subjects diagnosed with AD from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database with at least one abnormal Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) assessment were included. Individuals were assigned to a discovery sample and a sensitivity analysis sample (moderate and mild dementia, respectively) and a subset of subjects provided neuropathological data (n = 284). Individuals from the Washington Heights and Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP) served as validation sample. Patterns of presentation of EPS were identified employing categorical principal component analysis (CATPCA). Six principal components were identified in both mild and moderate AD samples: (I) hand movements, alternating movements, finger tapping, leg agility (“limbs bradykinesia”); (II) posture, postural instability, arising from chair, gait and body bradykinesia/hypokinesia (“axial”); (III) limb rigidity (“rigidity”); (IV) postural tremor; (V) resting tremor; (VI) speech and facial expression. Similar results were obtained in the WHICAP cohort. Individuals with hallucinations, apathy, aberrant night behaviors and more severe dementia showed higher axial and limb bradykinesia scores. “Limb bradykinesia” component was associated with a neuropathological diagnosis of Lewy body disease and “axial” component with reduced AD-type pathology. Patterns of EPS in AD show distinct clinical and neuropathological correlates; they share a pattern of presentation similar to that seen in Parkinson’s disease, suggesting common pathogenic mechanisms across neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Extrapyramidal signs, CATPCA, Lewy bodies

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia in the elderly [1]. Although cognitive impairment is a signature feature of the disease, psychiatric manifestations and extrapyramidal signs (EPS) are extremely common with the latter prevalence ranging from 12 % in mild stages [2] up to 92 % in severe stages of the disease [3]. In addition, the presence of EPS is associated with faster rates of cognitive decline in AD [4].

The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS [5]), the main tool to assess EPS in Parkinson’s disease (PD), has been extensively employed to rate the severity of movement disorders in other neurodegenerative diseases, including AD [6]. Several studies have explored the structure of the scale in PD samples, utilizing a variety of statistical approaches and producing conflicting results.

We employed a nonlinear principal component analysis (CATPCA [7]) to explore patterns of extrapyramidal signs in individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The analysis was first carried out in a discovery data set composed of subjects diagnosed with moderate AD dementia who were in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set (NACC UDS) database. Subsequently, sensitivity analyses employed an independent data set of UDS subjects diagnosed with mild AD dementia. Finally, a third independent multi-ethnic data set was used to provide further confirmation. Computed components were examined for potential association with cognitive and neuropsychiatric features and ultimately neuropathological manifestations. In addition, results were compared with previous studies, in particular those in PD.

Methods

Study data sets

The NACCUDS: the discovery study population consisted of patients enrolled in the NACC UDS [8] between September 2005 and September 2013. Patients were seen regularly at 1 of 34 current and past Alzheimer’s disease centers (ADCs). The Uniform Data Set (UDS) includes standardized data collection forms capturing information on demographic and clinical characteristics. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their study partners. Research using the NACC database was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington. More detailed information on the NACC database can be found online (http://www.alz.washington.edu/).

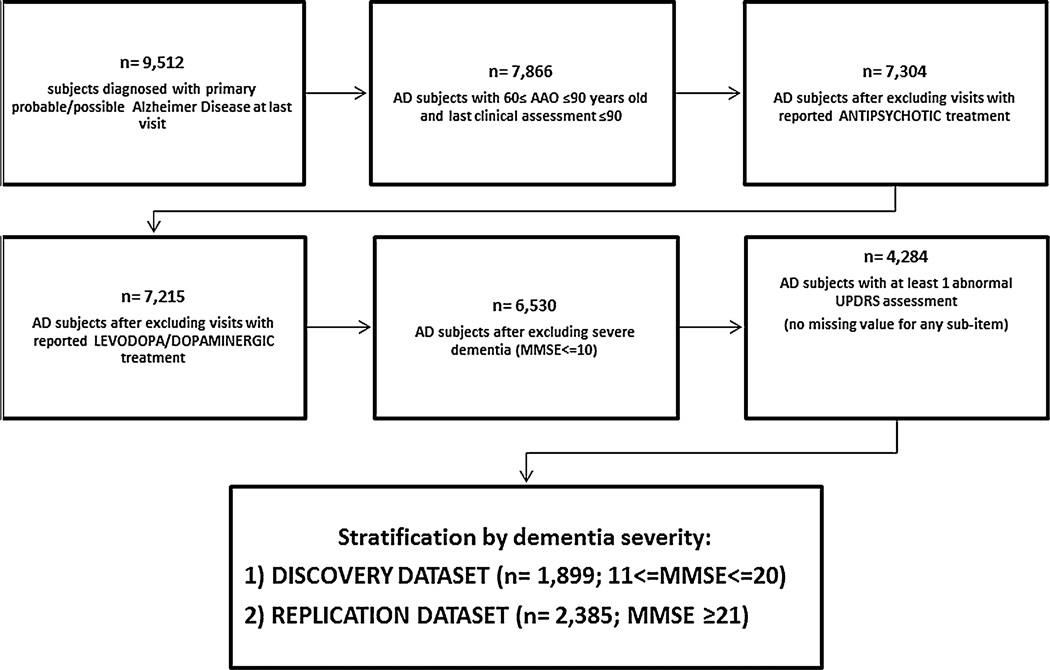

For this study, subjects (1) were 60–90 years old at the last UDS visit; (2) had a diagnosis of probable or possible AD according to the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria [9] at the last UDS visit; (3) had an abnormal Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) score (mild to severe impairment) with no missing scores in any sub-item at the last visit; and (4) had mild or moderate AD dementia. Moderate dementia was defined as a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score between 10 and 20, and mild dementia was defined as an MMSE equal to or greater than 21. The main sample comprised subjects with moderate AD dementia, and a sensitivity analysis was performed on subjects with mild AD dementia. Individuals that reported antipsychotic medication use at any time were excluded from the analyses. Patients treated with anti-Parkinson agents (levodopa and/or dopaminergic agents) were also excluded. Subject selection flowchart is reported in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart shows selection criteria and resulting sample sizes at each step

WHICAP data set: the Washington Heights and Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP) is a prospective, population-based study of aging and dementia in Medicare recipients aged 65 years and older residing in northern Manhattan (Washington Heights, Hamilton Heights and Inwood), described previously [10]. The diagnoses of probable or possible AD were defined using NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. The population from which participants were drawn represents three defined ethnic categories (Caribbean Hispanic, African American and European Caucasian ancestry; n = 633, n = 280 and n = 115 cases, respectively) and inclusion/exclusion criteria mirrors those described for the NACC study sample. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants using procedures approved by the institutional review board.

Variables

The motor UPDRS examination includes 27 rated items each scored on a 0 (no impairment) to 4 (severe impairment) ordinal scale. The total motor UPDRS scores range from 0 to 108. The Modified Columbia UPDRS (MC-UPDRS) comprises 11 out of the original 27 items: speech, facial expression, tremor at rest in any limb (one single item instead of the standard four items), neck rigidity, right arm rigidity, left arm rigidity, right leg rigidity, left leg rigidity, posture (one item), gait, body bradykinesia and hypokinesia. Each feature in this modified instrument is also rated on a scale of 0–4 (max total score is 44). The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) was used to collect information regarding the presence and severity (range 0–4, with 4 indicating severe impairment) of depression, hallucinations, delusions and nighttime behaviors, among others. Global cognitive function was measured by the MMSE [11] and the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes score (CDR-SB) [12].

Additional clinical characteristics of interest were sex, age at evaluation and age at onset of cognitive decline. Age at onset was assessed from direct observation or subject and/or informant report.

Neuropathological (NP) data were available for a subset of UDS subjects who died and had consented for autopsy. For these subjects, data on (1) the primary NP diagnosis [13], (2) Braak stage, (3) neuritic and diffuse plaque frequency and (4) Lewy body pathology [14] were available. Criteria applied by the neuropathologist to determine the described features are in the NACC Neuropathology Guidebook (https://www.alz.washington.edu/NONMEMBER/NP/npguide9.pdf). For most analyses, NP categories were collapsed, e.g., categories were created for Braak stage: no pathology detected (0), lesser stages (I through II), intermediate stages (III and IV) and two higher stages categories (V and VI, respectively, representing extensive neurofibrillary tangles in association cortices and in primary sensory cortex).

Statistical analysis

Nonlinear PCA (also known as “categorical principal component analysis”—CATPCA) has been developed as an alternative to standard PCA [7, 15] to analyze categorical data, which have a nonlinear relationship with study variables. Briefly, CATPCA transforms categorical/ordinal/continuous variables into quantitative variables (through a technique called “optimal scaling”), such that as much as possible of the variance is accounted for in the analysis (“VAF”, i.e., PC’s eigenvalues divided by the number of the original variables). Because there are no distributional assumptions, skewed distributions are allowed. Analyses were conducted using polychoric correlation [16] (polychoric and polyserial correlations, R package version 0.7–7, http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=polycor). Categories with very low frequencies can cause model instability; thus, categories with low frequency (≤8) were merged in all analyses [17].

The Kaiser criterion (selecting of PC based on eigenvalue ≥1), scree plot inspection [18] and parallel analysis [19] were used to choose the optimal model in terms of number of components to retain. Variables were selected if VAF ≥0.3, traditionally considered the threshold [20] to prune items with little contribution to the final model. Ultimately, we identified outliers, defined as individuals with aberrant loadings, i.e., exceeding ±4 standard deviation for one or more PCs. After variable and subject pruning based on VAF and outliers, respectively, CATPCA was repeated. Cronbach’s α, a measure of internal consistency [21], is also provided for the combination of PCs retained in the final model; a level of alpha that indicates an “acceptable” level of reliability has traditionally been 0.70 or higher. Transformed variables were then subjected to varimax rotation [22] for more a readable interpretation of the results.

Study demographics were explored through χ2 statistics, Kruskal–Wallis test (KW) or analysis of variance, depending on the nature of the variable examined. The scores of the obtained components were also used as main predictors, and the associations with neuropathological diagnosis were studied in ordinal logistic regression models. Primary diagnosis at autopsy served as the main outcome, with AD as the reference category, and excluding those individuals with rare or mixed diagnoses. Analyses were adjusted for sex, age at death and age at dementia onset as covariates. We also computed the association between components and (1) neuropsychiatric/cognitive measures and (2) neuropathological manifestations (Braak stage, LB presence and distribution) using a KW test or the Jonckheere trend test.

Monte Carlo methods reporting 99 % confidence intervals and utilizing 10,000 samples were employed when data were too sparse or unbalanced to meet the assumptions of asymptotic methods. False discovery rate (FDR) [23] control was used to correct for multiple testing. Analyses were performed using R version 3.0.2 and SPSS version 22.

Results

Age at last evaluation was similar between moderate and mild demented groups (79.4 vs. 79.0; ANOVA, p = 0.09). There were more women with moderate dementia (χ2: p < 0.001), a younger age at onset of dementia (ANOVA: p < 0.001) and a younger age at death (ANOVA, p = 0.05) (see Table 1). Finally, those with moderate dementia had a higher UPDRS median score (KW test, p < 0.001) compared to those with mild dementia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of NACC and WHICAP subjects

| NACC | WHICAP N = 1028 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate dementia N = 1899 | Mild dementia N = 2385 | Autopsy data set N = 284 | ||

| Women (%) | 57.1 | 51.1 | 38.0 | 69.1 |

| Mean age at last evaluation (SD) | 79.4 (6.4) | 79.0 (6.4) | 82.8 (6.0) | 83 (5.4) |

| Age at onset (SD) | 73.5 (6.4) | 74.4 (6.7) | 75.7 (6.0) | 81 (6.0) |

| Education (SD) | 13.6 (4.0) | 14.8 (3.4) | 15.3 (3.0) | 7 (5.0) |

| Median UPDRS (IQR) | 9 (11) | 6 (9) | 11 (12) | 1 (4)a |

| Number of subjects with autopsy data | 182 | 102 | – | NA |

| Mean age at death (SD) | 83.6 (6.1) | 84.7 (6.3) | 84.0 (6.0) | NA |

NACC National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center, WHICAP Washington Heights and Inwood Columbia Aging Project, IQR interquartile range

Total score computed using the Modified Columbia UPDRS (11 items)

CATPCA in NACC—moderate AD individuals

First, several models were explored: scree plot inspection, Kaiser criterion and parallel analysis converged toward seven PCs as the optimal solution. Examination of each of the 27 item’s VAF showed high value for all, but the “face/lips/chin resting tremor” item (VAF <0.3). This item was then excluded and CATPCA repeated with the remaining 26 items.

Analyses again retrieved seven PCs (total VAF = 73.2 %; Cronbach’s α = 0.985). Outlier detection for one or more PCs identified 36 individuals (23 outliers on a single PC, five on two PCs, six on three PCs and two on four PCs). The outliers were mostly patients with resting tremor in the feet. Their exclusion resulted in no remaining VAF for those two variables, which were excluded from further analyses.

Final analyses comprised 1861 remaining individuals and 24 items. Scree plot inspection, Kaiser criterion and parallel analysis indicated an optimal model with six PCs: total VAF accounted for 70.9 %, Cronbach’s α was 0.98 and all 24 remaining items showed a VAF >0.5. Items measuring hands movement, alternate movements, finger tapping and leg agility loaded on the first PC (“limb bradykinesia” component); posture, postural instability, arising from chair, gait and body bradykinesia and hypokinesia loaded on the second component (“axial” component). The third PC included neck, and upper and lower limbs rigidity items (“rigidity” component). The fourth and fifth PCs comprised postural and resting tremor items, respectively (“postural tremor” and “resting tremor” components). Finally, speech and facial expression items loaded on the sixth PC (“speech/facial” component). The CATPCA plot shown in Fig. 2 depicts the relationship between the UPDRS items included in the analysis: each item is represented by a vector, the length of which accounts for the magnitude of its loading on the selected component and the angles between vectors represent the strength of their association. The item’s loadings (after VARIMAX rotation) are reported in Table 2.

Fig. 2.

Biplot of the third and fourth component derived from the NACC sample (moderate AD). The length of the vectors in the two-dimension plot indicates the magnitude of the loadings, while cosines of the angles between the vectors indicate the strength of their correlations

Table 2.

Rotated loadings (i.e., each variable’s correlation with the components) for the NACC and WHICAP data sets. Only loadings ≥0.4 are shown

| PCs | NACC study | WHICAP study | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate dementia | Mild dementia | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Speech | 0.821 | 0.822 | 0.874 | ||||||||||||

| Facial expression | 0.850 | 0.852 | 0.850 | ||||||||||||

| Tremor at rest—RH | 0.903 | 0.898 | Excluded due to low correlation with other itemsa | ||||||||||||

| Tremor at rest—LH | 0.903 | 0.899 | |||||||||||||

| Action tremor—RH | 0.953 | 0.945 | NAb | ||||||||||||

| Action tremor—LH | 0.956 | 0.948 | |||||||||||||

| Rigidity—neck | 0.630 | 0.586 | 0.733 | ||||||||||||

| Rigidity—upper right limb | 0.806 | 0.825 | 0.831 | ||||||||||||

| Rigidity—upper left limb | 0.824 | 0.822 | 0.863 | ||||||||||||

| Rigidity—lower right limb | 0.816 | 0.820 | 0.869 | ||||||||||||

| Rigidity—lower left limb | 0.826 | 0.819 | 0.865 | ||||||||||||

| Finger taps—RH | 0.820 | 0.801 | NAb | ||||||||||||

| Finger taps—LH | 0.807 | 0.811 | |||||||||||||

| Hand movements—RH | 0.839 | 0.828 | |||||||||||||

| Hand movements—LH | 0.832 | 0.826 | |||||||||||||

| Alternating movement—RH | 0.812 | 0.777 | |||||||||||||

| Alternating movement—LH | 0.801 | 0.779 | |||||||||||||

| Leg agility—RL | 0.670 | 0.658 | |||||||||||||

| Leg agility—LL | 0.649 | 0.667 | |||||||||||||

| Posture stability | 0.825 | 0.771 | |||||||||||||

| Arising from chair | 0.703 | 0.728 | |||||||||||||

| Posture | 0.823 | 0.807 | 0.788 | ||||||||||||

| Gait | 0.791 | 0.656 | 0.856 | ||||||||||||

| Body bradykinesia/hypokinesia | 0.613 | 0.606 | 0.818 | ||||||||||||

RH right hand, LH left hand, RL right limb, LL left limb

Present as a single item in the WHICAP data set

Items not available in the WHICAP data set

CATPCA in NACC—mild AD individuals

Identical procedures were applied to the replication data set (mild AD) and only the final model is discussed here. Again, a six PCs solution was found to be the best model, with 2295 individuals and 24 items grouped in the same fashion as described in the moderate dementia sample (“limb bradykinesia”, “axial”, “rigidity”, “postural tremor”, “resting tremor” and “speech/facial” components). Total VAF was 67.8 % with Cronbach’s α of 0.98. Rotated components are also shown in Table 2.

CATPCA in WHICAP data set

CATPCA performed on the MC-UPDRS 11 items in the WHICAP data set yielded three PCs; resting tremor (which is represented by a single item) was excluded due to its low VAF (<0.3), along with 33 outliers. The final model had 10 items and 995 remaining individuals (total VAF = 72.7 %, Cronbach’s α = 0.96). The first PC was made up of the five rigidity items (“rigidity” component), while the second PC comprised posture, gait, body bradykinesia and hypokinesia (“axial” component). The third PC comprised speech and facial expression (“speech/facial”).

Component scores and clinical features

NACC mild and moderate AD subjects were then merged into a single data set and CATPCA re-run on the combined sample with identical methods as discussed above. The six components were correlated to cognitive and neuropsychiatric features assessed at the same visit: individuals with reported hallucinations at the NPI showed higher “limb bradykinesia” and “axial” scores (KW test: p < 0.001 and p = 0.003, respectively), as well as those with apathy (KW test: p < 0.001 and p = 0.002, respectively) and night aberrant behaviors (KW test: p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively). In addition, those with delusions showed higher “axial” score (KW test: p < 0.001), while higher “limb bradykinesia” scores were associated with reported cognitive fluctuations. Ultimately, “limb bradykinesia” and “axial” components were correlated with dementia severity as measured by the CDR-SB (trend test: p < 0.001 for both PCs).

Component scores and NP features

A subset of the patients included in this report died and were autopsied providing in the availability of NP data. These individuals were included if they had a clinical evaluation within 2 years prior to death (N = 284). AD was reported as the primary NP diagnosis for 189 individuals (68 %). Other primary diagnoses were as follows: 16 vascular dementia (6 %), 9 frontotemporal dementia (3 %), and 5 hippocampal sclerosis (2 %). Twenty-two individuals had a “high likelihood” of Lewy body disease (LBD) according to the 2005 Consensus criteria. Ten individuals, despite being diagnosed with dementia, did not have substantial pathology to explain their cognitive symptoms, i.e., normal brains (3 %). Finally, 27 subjects had very rare diagnoses (one individual per category, <1 %) or had multiple coexisting pathologies, such as no diagnosis could be assigned as a predominant cause of dementia.

The “limb bradykinesia” component was associated with receiving an LBD diagnosis at autopsy (LBD vs. AD: OR = 1.89, CI = 1.25–2.87, p = 0.003). No significant results were found for the other diagnoses after correction for multiple comparisons.

Restricting analyses to individuals with AD as the primary diagnosis, only Braak stage for neurofibrillary degeneration was significantly associated with computed components after multiple testing correction: higher Braak stages were associated with lower “axial” impairment (trend test, p = 0.003).

Discussion

Based on the presence or absence of EPS, two AD sub-phenotypes can be identified:”cognitive/pure” and “cognitive and motor”, mirroring the classification of PD into “motor” and “motor and cognitive” forms [24]. Such distinction is extremely important, as individuals with AD and EPS show a faster course of the disease [4]. Knowing this information could guide clinicians and families in planning the course of the disease.

We investigated patterns of EPS in three different sets of individuals diagnosed with AD. Contrary to previous studies which grouped the UPDRS items into distinct domains, either arbitrarily or by applying classifications derived from PD studies, we employed specific statistical tools that took into account the nature of the scale and carefully classified subjects according to their phenotypic profiles. CATPCA reduced the 27-item scale to six components, and results found in the discovery sample were confirmed by two independent data sets which differed in terms of disease severity (the NACC mild dementia data set) or materials and methods adopted (the WHICAP study). The latter employs a shorter version of the UPDRS (MC-UPDRS) that mostly relies on observation/passive exploration of the patient, in contrast to the standard UPDRS, which contains tasks demanding a fairly good comprehension of commands (e.g., hand movement, alternate movements, etc.). The MC-UPDRS allowed us to analyze a mixed sample of individuals in terms of disease severity (ranging from mild to severe AD). Nevertheless, results from the WHICAP sample closely resembled those observed in the two NACC samples.

We stratified the NACC sample by severity of dementia, because we did not assume a priori that EPS patterns would be identical across different disease stages. Still, severely demented patients were excluded to avoid biased analyses, as several items (especially, items loading on the “bradykinesia limbs” component) could be affected by apraxia impairment, a common condition of disease’s severe stages [25]. Mild and moderate dementia revealed nearly identical patterns, adding strength to our findings. However, compared to the moderate AD group, the mild AD group had a slightly higher variance for the “resting tremor” component, which in turn corresponded with a lower variance for the “axial” component. Although differences were minimal, this discrepancy suggests that tremor tended to be associated with a more benign profile of the disease, whereas axial features may be linked to a more aggressive course. This notion has been observed extensively in PD [26]: tremor is absent in 25 % of PD cases, and disease sub-types characterized by tremor features show a more benign course compared to non-tremor forms.

In PD, tremor has a low correlation and a different progression rate compared to the other EPS, suggesting that it may be linked to independent pathophysiological processes [26]. The independent nature of tremor was confirmed in the WHICAP study, where tremor, represented by a single item, was indeed excluded from the analysis because of its low correlation with the other items.

Previous studies on idiopathic PD showed “limbs bradykinesia” items clustering along with rigidity items in early disease stages. Results were inconsistent across studies [27–29], possibly due to different analytic methods, disease stages at enrollment or sample sizes. Nevertheless, a recent study [30] showed that, although lateralization dominates early stages, as disease progresses, the model veers toward resembling our results more closely. In addition, Evans and colleagues [31] studied UPDRS score change over time in a cohort of PD cases. The authors found that axial features had the highest variation in the rate of progression, proving to be the major contributor to heterogeneity in the longitudinal evolution of PD. Again, this observation is somewhat consistent with our results, where the “axial” component shows higher variance in the moderate AD sample compared to mild AD.

Patterns of EPS were also associated with distinct neuropathological profiles. Higher “limb bradykinesia” component scores were correlated with receiving a primary neuropathologic diagnosis of LBD; on the contrary, crude observation of LB presence was not related to any component, which ultimately underlines the importance of AD type and LB pathology co-expression [32] as recognized by the latest DLB diagnostic criteria [14]. In subjects with AD as a primary diagnosis, AD pathology, as measured by Braak staging, was associated with lower “axial” impairment. Therefore, these two components point to non-AD pathology, and, at the same time, to more severe cognitive impairment, since they both also correlate with higher CDR scores. Similar conclusions were reported by Selikhova and colleagues [33] in a series of autopsies of PD patients, although subjects were categorized by the investigator in a different fashion: non-tremor disease’s sub-type was associated with neocortical Lewy bodies, the latter being more common (along with AD-type pathology) in demented subjects. Although LB and AD-type pathology co-expression was not investigated, their conclusions match ours to some extent: in our analyses “limb bradykinesia” and “axial” components were clearly independent of tremor and associated with non-AD pathology and primary diagnosis.

Ultimately, several neuropsychiatric features strongly correlated with “limb bradykinesia”, which is in line with previous reports showing an association between hallucinations and LB pathology at autopsy in those with clinical AD [34].

This investigation has limitations. First, exclusion of visits with reported antipsychotic and antiparkinsonian agents, although limiting bias for drug-induced events, does not rule out that EPS or hallucinations were independently present. Second, although we stratified by disease severity, other sample’s heterogeneity were not fully investigated, e.g., disease duration which would point to other important aspects such as rapidity of the disease’s course; in addition, we included both probable and possible AD diagnosis to maximize our sample size but, at the same time, this increased the heterogeneity of our sample. Third, 90 % of the patients reported using one or more available treatments (including acetylcholinesterase inhibitors). This may have limited our ability to disentangle the potential effects of these medications on EPS and the generalizability of our findings to untreated individuals. Finally, the NACC database collects data from AD research centers and is not population based. Additionally, patients who are followed up and provide consent for brain autopsy may not be typical of any population and represent only a small portion of the initial clinical sample. NP data respond to standardized and fixed variables disclosed by the NACC study: more specific measures would be need for a better insight into the underlying neuropathological profiles of the described EPS patterns.

Our analyses in mild and moderate AD confirm several notions previously observed in PD, thus corroborating the view that common pathophysiological processes might be shared across different neurodegenerative diseases. These findings could potentially drive novel unifying experimental settings in terms of diagnostic tools and new treatments.

Acknowledgments

The NACC database is funded by the NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data were contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI David Teplow, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP) and P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD). Dr. Tosto was supported by the DoD Grant W81XWH-12-1-0013. Dr. Tosto had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Tosto, Ms. Monsell, Dr. Hawes and Dr. Mayeux report no disclosures.

Abbreviations

- TRACTRHD/LHD

Postural tremor of right and left hand

- TRESRHD/LHD

Resting tremor of right and left hand

- TAPSRT/LF

Finger tapping of right and left hand

- HANDMOVR/L

Hand movements of right and left hand

- LEGRT/LF

Leg agility of right and left leg

- RIG-NECK/DLORT/DLOLF/DUPRT/DUPLF

Rigidity of neck, right leg, left leg, right arm and left arm

- FACEXP

Face expression

- BRADYKIN

Body bradykinesia and hypokinesia

- ARISING

Arising from chair

- POSSTAB

Postural stability

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical standards Studies have been approved by the Institutional Review Boards and have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflicts of interest None.

References

- 1.Tosto G, Reitz C. Genome-wide association studies in Alzheimer’s disease: a review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2013;13:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11910-013-0381-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portet F, Scarmeas N, Cosentino S, Helzner EP, Stern Y. Extrapyramidal signs before and after diagnosis of incident Alzheimer disease in a prospective population study. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1120–1126. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell SL. Extrapyramidal features in Alzheimer’s disease. Age Ageing. 1999;28:401–409. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scarmeas N, Albert M, Brandt J, Blacker D, Hadjigeorgiou G, Papadimitriou A, Dubois B, Sarazin M, Wegesin D, Marder K, Bell K, Honig L, Stern Y. Motor signs predict poor outcomes in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;64:1696–1703. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000162054.15428.E9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fahn S, ERM of the UDC . Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Florham Park: Macmillan Health Care Information, NJ; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richards M, Marder K, Bell K, Dooneief G, Mayeux R, Stern Y. Interrater reliability of extrapyramidal signs in a group assessed for dementia. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:1147–1149. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530230055021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linting M, Meulman JJ, Groenen PJ, van der Koojj AJ. Nonlinear principal components analysis: introduction and application. Psychol Methods. 2007;12:336–358. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, Deitrich WD, Jacka ME, Wu J, Hubbard JL, Koepsell TD, Morris JC, Kukull WA, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the uniform data set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21:249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group* under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–940. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Cheng R, Barral S, Reitz C, Medrano M, Lantigua R, Jiménez-Velazquez IZ, Rogaeva E, St George-Hyslop PH, Mayeux R. Identification of novel loci for Alzheimer disease and replication of CLU, PICALM, and BIN1 in Caribbean Hispanic individuals. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:320–328. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyman BT, Trojanowski JQ. Editorial on consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer disease from the National Institute on Aging and the Reagan Institute Working Group on diagnostic criteria for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:1095–1097. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199710000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKeith I, Dickson D, Lowe J, Emre M, O’brien J, Feldman H, Cummings J, Duda J, Lippa C, Perry E, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies Third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linting M, van der Kooij A. Nonlinear principal components analysis with CATPCA: a tutorial. J Pers Assess. 2012;94:12–25. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2011.627965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muthén B, Kaplan D. A comparison of some methodologies for the factor analysis of non-normal Likert variables. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1985;38:171–189. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markus MT. Bootstrap confidence regions in nonlinear multivariate analysis. DSWO Press, Leiden University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cattell RB. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivar Behav Res. 1966;1:245–276. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cota AA, Longman RS, Holden RR, Fekken GC. Comparing different methods for implementing parallel analysis: a practical index of accuracy. Educ Psychol Measur. 1993;53:865–876. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Comrey AL, Lee HB. A first course in factor analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaiser HF. The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1958;23:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benjamini Y, Drai D, Elmer G, Kafkafi N, Golani I. Controlling the false discovery rate in behavior genetics research. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graham JM, Sagar HJ. A data-driven approach to the study of heterogeneity in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: identification of three distinct subtypes. Mov Disord. 1999;14:10–20. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199901)14:1<10::aid-mds1005>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Della Sala S, Lucchelli F, Spinnler H. Ideomotor apraxia in patients with dementia of Alzheimer type. J Neurol. 1987;234:91–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00314108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helmich RC, Hallett M, Deuschl G, Toni I, Bloem BR. Cerebral causes and consequences of parkinsonian resting tremor: a tale of two circuits? Brain. 2012;135:3206–3226. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stebbins GT, Goetz CG. Factor structure of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale: motor examination section. Mov Disord. 1998;13:633–636. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vassar SD, Bordelon YM, Hays RD, Diaz N, Rausch R, Mao C, Vickrey BG. Confirmatory factor analysis of the motor unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. Parkinson’s Dis. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/719167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stochl J, Boomsma A, Ruzicka E, Brozova H, Blahus P. On the structure of motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:1307–1312. doi: 10.1002/mds.22029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brakedal B, Tysnes O-B, Skeie GO, Larsen JP, Müller B. The factor structure of the UPDRS motor scores changes during early Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:617–621. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans JR, Mason SL, Williams-Gray CH, Foltynie T, Trotter M, Barker RA. The factor structure of the UPDRS as an index of disease progression in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinson’s Dis. 2011;1:75–82. doi: 10.3233/JPD-2011-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colom-Cadena M, Gelpi E, Charif S, Belbin O, Blesa R, Marti MJ, Clarimón J, Lleó A. Confluence of alpha-synuclein tau, and beta-amyloid pathologies in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72:1203–1212. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selikhova M, Williams D, Kempster P, Holton J, Revesz T, Lees A. A clinico-pathological study of subtypes in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2009;132:2947–2957. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toledo JB, Cairns NJ, Da X, Chen K, Carter D, Fleisher A, Householder E, Ayutyanont N, Roontiva A, Bauer RJ, et al. Clinical and multimodal biomarker correlates of ADNI neuropathological findings. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2013;1:65. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]