Abstract

Purpose

This study estimates the prevalence in US counties of opioid patients who use large numbers of prescribers, the amounts of opioids they obtain, and the extent to which their prevalence is predicted by ecological attributes of counties, including general medical exposure to opioids.

Methods

Finite mixture models were used to estimate the size of an outlier subpopulation of patients with suspiciously large numbers of prescribers (probable doctor shoppers), using a sample of 146 million opioid prescriptions dispensed during 2008. Ordinary least squares regression models of county-level shopper rates included independent variables measuring ecological attributes of counties, including rates of patients prescribed opioids, socioeconomic characteristics of the resident population, supply of physicians, and measures of healthcare service utilization.

Results

The prevalence of shoppers varied widely by county, with rates ranging between 0.6 and 2.5 per 1000 residents. Shopper prevalence was strongly correlated with opioid prescribing for the general population, accounting for 30% of observed county variation in shopper prevalence, after adjusting for physician supply, emergency department visits, in-patient hospital days, poverty rates, percent of county residents living in urban areas, and racial/ethnic composition of resident populations. Approximately 30% of shoppers obtained prescriptions in multiple states.

Conclusions

The correlation between prevalence of doctor shoppers and opioid patients in a county could indicate either that easy access to legitimate medical treatment raises the risk of abuse or that drug abusers take advantage of greater opportunities in places where access is easy. Approaches to preventing excessive use of different prescribers are discussed.

Keywords: opioids, abuse, diversion, multiple prescribers, geographic variation, pharmacoepidemiology

INTRODUCTION

The USA is experiencing what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention terms an “epidemic” of prescription opioid abuse.1,2 The annual death toll from prescription opioid overdoses rose fourfold between 1999 and 2011, from 4030 to 16 651; is now twice the number of heroin and cocaine overdose deaths combined; and is approaching the numbers of traffic accident deaths.3,4 An estimated half-million emergency department visits during 2011 resulted from nonmedical use of prescription opioids, about 10 times more than in 1995.5,6 Similar increases were seen in admissions to treatment for prescription opioid abuse.7,8

Like all epidemics, opioid abuse is not uniformly prevalent in all places at the same time, but little attention has been given to the ecology of opioid abuse.9 Studies have documented small-area “hot spots” of opioid overdose deaths in the USA, as well as regional variation in self-reported nonmedical use, in drug-related visits to sentinel emergency departments in 12 metropolitan areas, in surveys of arrestees’ drug use in five cities, and in calls to poison control centers that cover about one-third of the three-digit ZIP (3DZ) codes in the USA.10–14 However, most studies have focused on limited numbers of locations and have been descriptive rather than analytic and ecological.9,15,16 That is, few examined the extent to which the prevalence of opioid misuse is associated with characteristics of places.12,17,18 Some report finding urban and rural differences in abuse prevalence rates; one study found associations among prevalence of calls to poison control centers and proportion of White residents, of individuals age 18–24 years, and median household income.12,19–23

A widespread concern is that unlike the use of illicit drugs, the current epidemic is iatrogenic, the result of clinical treatment that escalates into abuse and addiction. But whereas nearly all opioids originate with physicians’ prescriptions, most of those abusing them report that they obtained them from friends, relatives, or dealers.24 This suggests that nonmedical use of opioids is concentrated in social networks of users and dealers, located in particular places, perhaps having distinctive socioeconomic characteristics, similar to patterns found for users of illicit drugs.25–30 Recent research shows large variation among counties in prevalence of overdose deaths but does not address differential exposure to opioid prescribing.11 Our earlier research finds wide geographic variation among counties in opioid-prescribing rates but does not examine how this is associated with rates of abuse.31 The present study examines whether and to what extent geographic variation in opioid abuse is predicted by exposure to prescribed opioids and by other ecological attributes of counties.

Opioid abuse is a covert activity that cannot be observed directly. One must therefore rely on various indicators of abuse, such as overdose deaths, treatment admissions, emergency department visits, and self-reports. We use another indicator—patients who obtain opioid prescriptions from large numbers of different prescribers, a risk factor for dependence, abuse, and overdose death.21,32–35

Research objective

This study has several aims. The first is to describe geographic variation in opioid misuse at national, state, and county levels using indicators that can be derived from prescription data: the prevalence of persons obtaining opioid prescriptions from large numbers of different doctors and the amounts of opioids so obtained. The second objective is to estimate the extent to which prevalence of using large numbers of prescribers varies according to several ecological attributes of counties, including the prevalence of prescribed opioids. Finally, we discuss the implications of our findings for research, practice, and policy.

METHODS

Data sources and sample

IMS Health, Inc. provided us the records of 146.1 million prescriptions for drugs dispensed during 2008 that contained all forms and dosages of opioids most often prescribed for analgesia: buprenorphine, codeine, dihydrocodeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, methadone, oxycodone, oxymorphone, propoxyphene, and tramadol. IMS purchased these prescription records for market research purposes from a nationwide network of approximately 37 000 retail pharmacies, specialty pharmacies, and mail services—comprising 76% of all such outlets in the USA in 2008. Participating pharmacies provided information about all opioid medications they dispensed that year (except antitussives), including drug amounts and strengths, prescribers, method of payment, third-party payers, and patient’s age and sex, but no clinical information. To provide a summary measure for analysis, we converted types and amounts of opioids dispensed to morphine equivalent grams.36,37

IMS Health, Inc. used a probabilistic matching procedure to link all prescriptions dispensed by different pharmacies to 48.4 million unique patients using encrypted information about patients’ date of birth, gender, name, and address, and third-party payer ID. We exploited these prescriptions linked to unique patients to count the number of different prescribers they used and to identify those obtaining prescriptions from large numbers of providers. Lacking patients’ addresses, we used the providers’ business address ZIP code to locate patients in counties. Patients obtaining prescriptions in multiple counties were counted as active in each county.

Several attributes of counties were measured for use as independent variables. Counts of persons prescribed opioids in each county were estimated using the IMS prescription data and converted to rates per 1000 residents using Bureau of Census population data. Socioeconomic characteristics of resident populations included percent urban; educational attainment; racial/ethnic composition; percent of residents under 65 years old who were Medicaid eligible and, separately, who lacked healthcare insurance; rates of persons living below federal poverty levels; and proportions receiving food stamps. Because food stamp use and poverty are highly correlated, we entered the food stamp rate in the equations as the ratio of persons in poverty to food stamp recipients. Measures of healthcare availability and utilization included numbers of physicians per 1000 residents (distinguishing emergency medicine, surgeons, pediatricians, psychiatrists, and all others); and rates per 1000 residents of in-patient days/year in short-term hospitals, of emergency department visits/year, and of surgeries per year. Residents’ race/ethnicity was self-identified in Bureau of Census data and included as a variable because it is associated with overdose death rates.38 All other measures except for opioid patients were extracted from the Area Resource File, a compilation of county-level population and health-related data from many sources.39 All county attributes are ecological characteristics of places and not of patients.

Statistical analysis

To derive total population estimates from this large non-random sample of 37 000 retail pharmacies, we used information acquired by IMS about total amounts of each specific opioid product sold to all retail pharmacies in each 3DZ code area by pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors. Amounts were distinguished by type of pharmacy: chain, independent, or other. We computed the ratio of the observed amounts dispensed by each type of pharmacy in the sample to amounts sold to all such pharmacies in each 3DZ. These ratios were used to calculate 3DZ-specific weights to inflate every record in the sample’s prescription data to estimate total numbers of opioid prescriptions dispensed in 2008 (223 million) by all retailers, assuming that quantities per prescription were the same in reporting and non-reporting pharmacies.

Estimating the number of unique patients required an additional step, because patients might make some purchases in sampled pharmacies and others in non-sampled pharmacies. We counted the number of observed pharmacies each patient in the sample used and assigned person weights that were the inverse of the probability that patients in the population with that number of pharmacies would be observed in the sample. State and nation-level estimates were developed independent of county-level estimates.

To count potential doctor shoppers, we developed a statistical model of the number of different prescribers used by patients, taking into account both random and systematic variation. We based the model on the 13.6 million unweighted patients in the sample (representing an estimated population of 19.0 million distinct weighted patients in the USA) who purchased at least one opioid prescription during the first 60 days of 2008. We then counted the number of different prescribers they used during the last 10 months of 2008.

We tested the hypothesis that the universe of patients with opioid prescriptions did not constitute a single population but rather a mixture of different subpopulations that differed in their needs for pain relief and their illicit/nonmedical use of opioids. Instead of defining in advance a threshold number of different prescribers and other indicators that distinguished probable diversion to nonmedical use from appropriate medical care, a strategy used in other studies 23,40–43, we used finite mixture modeling 44,45 (a statistical outlier detection technique) to identify different latent subpopulations of opioid purchasers who obtained prescriptions from differing numbers of prescribers. These models were used to fit a mixture of Poisson distributions with parameter λ where λ depended on the latent population, the age and gender of the patient, and whether any of the purchases involved cash. The fmm procedure in Stata statistical software was used for analysis.44

An outlying latent subpopulation having large numbers of different prescribers was assumed to comprise persons who acquired opioids for misuse, probably by “doctor shopping”—or obtaining prescriptions from different clinicians without revealing that they were doing the same with other prescribers. This analytic method and the nation-level estimates derived from them are described in greater detail in another paper available online.46

Identification of opioid abusers was only probabilistic, based upon the number of different prescribers they used. Diagnostic or other clinical information was not available to distinguish medically appropriate from suspicious patterns of opioid purchasing. Some patients with four prescribers, for example, had valid medical reasons; some may not have deceived their physicians but had badly coordinated care; and others were doctor shoppers obtaining opioids for their own misuse or for distributing to others. As the number of prescribers increased, so did the probability that the patient was a doctor shopper. For each county, we summed these estimated probabilities across all patients whose prescribers were in that county to estimate the number of doctor shoppers obtaining opioid prescriptions in that county. Because prescribed opioid use varied by age and gender, county and state rates were standardized by age and gender, based on Bureau of Census estimates of the nation’s population in 2008. Variation in estimated shoppers per 1000 standardized county residents and per 1000 standardized county opioid patients was expressed as the ratio of 25th to 75th quartiles and by the coefficient of variation (COV), a normalized measure of dispersion calculated as standard deviation divided by the mean. These statistics were computed separately for state rates per 1000 residents and per 1000 opioid patients. Ordinary least squares regression was used to identify ecological attributes of counties, including prevalence of patients treated with opioids, associated with higher rates of doctor shopping and to estimate the extent to which these attributes accounted for observed variation among counties in doctor shopping rates. In this study, we did not develop separate analyses for different types of opioids.

RESULTS

Testing models with differing numbers of latent populations, we determined that a model representing a mixture of three different latent populations most accurately predicted the observed distribution of the numbers of different prescribers used by patients. Including more populations did not further improve the fit. The largest latent population (83.8%) consisted of patients obtaining few opioid prescriptions during the last 10 months of 2008, seeing an average of 0.7 new prescribers. Another latent subpopulation of patients, comprising 15.5% of all opioid patients, obtained opioid prescriptions from an average of three new prescribers. A small outlier population, comprising 0.7% of all opioid patients, obtained an average of 32 opioid prescriptions from 9.3 new prescribers during the last 10 months of 2008, purchasing 4.2 million prescriptions or one of every 50 prescriptions dispensed. These contain 11.1 million grams of opioids or 5.4 million morphine equivalent grams—enough to supply each shopper with an average of 109 morphine equivalent mg per day all year. Forty percent of those we estimated to be probable doctor shoppers paid cash for at least one opioid purchase and obtained opioid prescriptions from an average of 15 different prescribers. The large numbers of prescriptions and prescribers suggest that most were probably doctor shoppers.

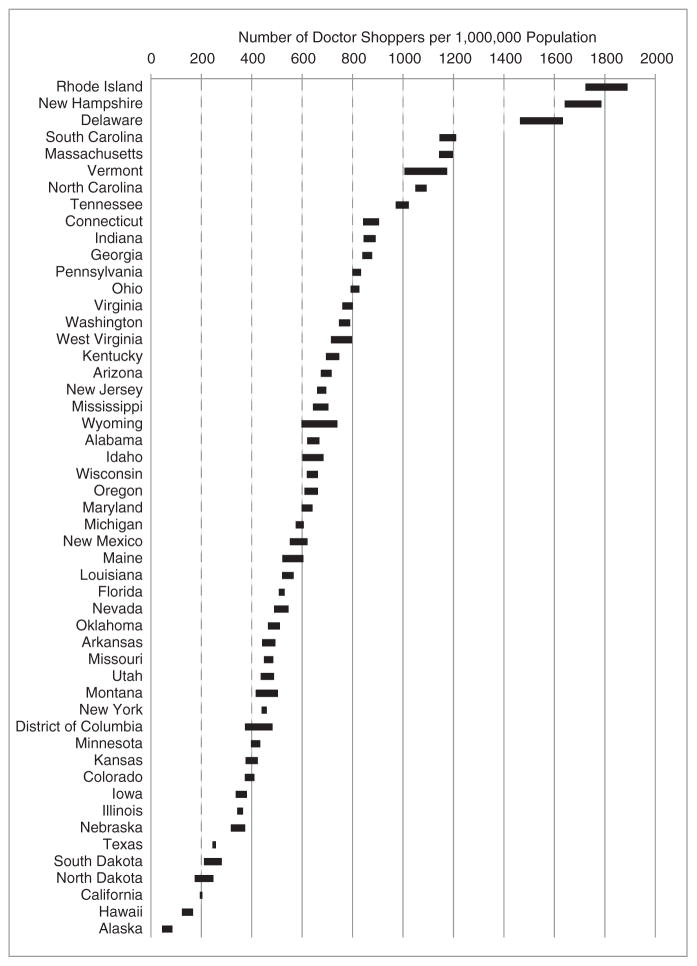

The prevalence of probable doctor shoppers per 1000 residents varied by state and geographic region, with the highest rates generally in the northeastern and southeastern states and the lowest in the Midwest (Figure 1). Among states arranged from lowest to highest rates, the rate in the 75th percentile was twice as high as the rate in the 25th percentile, and the COV = 0.55 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of doctor shoppers per 1 000 000 residents, by state, standardized by age and gender, 2008. Width of bars in figure indicates 95% confidence interval around point estimate

Table 1.

Variation in estimated doctor shopping prevalence among states and among counties, standardized by age and gender, 2008

| Number of doctor shoppers

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State-level prevalence

|

County-level prevalence*

|

|||

| Per 1000 residents | Per 1000 opioid patients | Per 1000 residents | Per 1000 opioid patients | |

| 25th percentile | 0.4 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 4.6 |

| Median | 0.6 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 7.9 |

| 75th percentile | 0.8 | 3.6 | 2.5 | 12.0 |

| Ratio of 75th to 25th percentile | 1.8 | 1.8 | 4.0 | 2.6 |

| Mean | 0.7 | 3.1 | 1.8 | 9.5 |

| Coefficient of variation | 0.55 | 0.58 | 1.06 | 1.36 |

Excludes 171 counties without physicians, according to the Area Resource File.

Source: Computed from LRx Data, 2008, obtained from IMS Health, Inc.

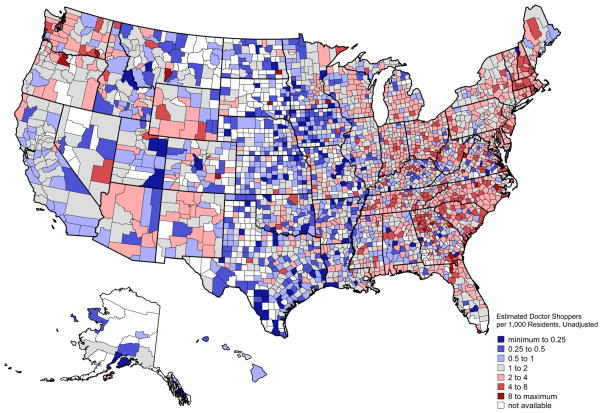

Variation among counties was significantly wider than among states, with rates differing from one county to another within a single state (Figure 2). In the bottom quarter of counties, 0.6 persons or fewer out of 1000 county residents were probable shoppers; in the top quartile, there were 2.5 or more—a fourfold difference (Table 1). Proportions of all opioid patients estimated to be shoppers also varied. In the average county, 1% of opioid patients was estimated to be a doctor shopper. Shopper prevalence in the bottom and top quartiles ranged from ≤4.6 to ≥12.0 per 1000 patients—a ratio of 2.6:1. The COV for county rates of doctor shoppers among opioid patients was large: 1.36.

Figure 2.

Prescription opioid doctor shoppers per 1000 residents, by county, standardized by age and gender, 2008

Table 2 shows an ordinary least squares regression model of county-level prevalence of doctor shoppers per 1000 residents and therapeutic exposure to opioids—measured as numbers of patients purchasing 1 or more prescriptions during 2008, per 1000 residents—as well as to other ecological attributes of counties. All variables in these equations are expressed as logarithms. As discussed earlier, only 0.7% of opioid patients were estimated to be probable doctor shoppers, so 99% are assumed to have been patients purchasing opioids for medical use. This variable measuring opioid exposure was excluded from model 1 and included in model 2.

Table 2.

Regression models of opioid doctor shoppers per 1000 residents in US counties, 2008: with and without covariates for opioid patients per 1000 residents

| Model 1

|

Model 2

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | p | b | SE | p | |

| Physicians per 1000 population | ||||||

| Pediatricians (a) | 0.1085 | 0.0363 | 0.003 | 0.0170 | 0.0283 | 0.55 |

| Emergency MDs (a) | 0.1739 | 0.0260 | p <0.001 | 0.1129 | 0.0202 | p <0.001 |

| Psychiatrists (a) | −0.0191 | 0.0323 | 0.55 | 0.0077 | 0.0251 | 0.76 |

| Surgeons (a) | 0.1234 | 0.0333 | p <0.001 | −0.0199 | 0.0261 | 0.45 |

| All other physicians (a) | 0.1975 | 0.0488 | p <0.001 | −0.0458 | 0.0383 | 0.23 |

| Medical utilization/1000 population | ||||||

| In-patient days/year in short-term hospitals (b) | −0.0515 | 0.0306 | 0.09 | −0.0666 | 0.0238 | 0.005 |

| Emergency dept visits/year (b) | 0.1570 | 0.0411 | p <0.001 | 0.1055 | 0.0319 | 0.001 |

| Surgeries/year (b) | −0.0192 | 0.0199 | 0.33 | −0.0342 | 0.0155 | 0.027 |

| Percent <65 years old without insurance, 2005 (c) | 0.0388 | 0.1101 | 0.72 | −0.1237 | 0.0857 | 0.15 |

| Percent Medicaid eligible <65 years old, 2004 (c) | 0.0771 | 0.1054 | 0.46 | 0.1964 | 0.0820 | 0.017 |

| Percent of county is urban (d) | 0.0591 | 0.0129 | p <0.001 | 0.0269 | 0.0100 | 0.007 |

| Percent completed high school but not college (d) | −0.7039 | 0.5048 | 0.16 | 0.3191 | 0.3931 | 0.42 |

| Percent college graduates (d) | −0.0271 | 0.1674 | 0.87 | −0.1176 | 0.1301 | 0.37 |

| Percent African-American (d) | 0.1272 | 0.0133 | p <0.001 | 0.0548 | 0.0105 | p <0.001 |

| Percent Hispanic (d) | −0.0201 | 0.0264 | 0.45 | −0.0118 | 0.0205 | 0.56 |

| Percent White non-Hispanic (d) | 0.8591 | 0.1020 | p <0.001 | 0.1461 | 0.0810 | 0.07 |

| Persons in poverty per 1000 (e) | −0.2010 | 0.1312 | 0.13 | −0.5253 | 0.1023 | p <0.001 |

| Disparity between poverty and food stamp rates (f) | −0.4275 | 0.0935 | p <0.001 | −0.2352 | 0.0728 | 0.001 |

| Opioid patients per 1000 (g) | 1.1666 | 0.0267 | p <0.001 | |||

| Constant | 0.8555 | 2.0404 | 0.68 | −4.8490 | 1.5912 | 0.002 |

| Model R2 | 0.3021 | 0.5786 | ||||

Excludes 171 counties without physicians, according to the Area Resource File.

Sources: Doctor shopper prevalence rates and (g) computed using LRx Data, 2008, obtained under license from IMS Health, Inc. Other data from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Area Resource File (ARF) Access System 2008. Original sources: (a) AMA Physician Master File, for year 2007; (b) American Hospital Association, Hospital Facilities Database, for year 2006; (c) Bureau of Census, Small Area Health Insurance Estimates; (d) Bureau of Census, extract, 2008; (e) Bureau of Census, Small Area Income Poverty Estimates, for year 2007; (f) Computed as the ratio of persons in poverty per 1000 (from (e)) to the number of food stamp recipients per 1000 (from Bureau of Census, County Level Food Stamp/SNAP Recipient File for year 2006).

In model 1, almost a third of the variation (R2 =30%) among counties in the prevalence of shoppers per 1000 residents was accounted for by ecological attributes other than opioid exposure (Table 2, model 1). These included county populations’ racial/ethnic composition, the ratio of food stamp use to persons in poverty, percent living in urban areas, rates of emergency department visits, and the supply of physicians in the counties (Table 2, model 1).

When the rate of opioid patients per 1000 residents was included (Table 1, model 2), the variation in doctor shopper prevalence accounted for by all measured attributes almost doubled (R2 = 0.58). This measure of therapeutic exposure to opioids in counties was therefore the strongest predictor of county doctor shopping rates (coefficient = 1.2). The correlation between supply of physicians and shopper prevalence was no longer statistically significant in model 2 (except for emergency department physicians) because the prevalence of opioid prescribing was strongly correlated with the number of prescribers in a county.31 Other ecological variables correlated with shopper prevalence in this second model included rates of in-patient hospitalization and emergency department visits, racial/ethnic composition of county residents, percent urban, and three measures related to income levels—percent of persons <65 years old who were Medicaid eligible, number of persons under federal poverty levels per 1000 residents, and the ratio of food stamp use to persons in poverty.

The small differences in shopper prevalence among larger US regions (e.g., Northeast, Southeast, Midwest, and West) became insignificant once differences in measured county attributes, including opioid exposure, were accounted for in regression models not shown here.

Patients obtaining opioid prescriptions in different locations were counted in each location. When we aggregated the numbers of shoppers in each state, the total exceeded the estimated number of unique shoppers by 30%, indicating that almost a third of doctor shoppers crossed state lines to obtain prescriptions. Cross-border doctor shopping accounts for some of the differences among state rates seen in Figure 1. Some states having the highest rates of shoppers per 1 000 000 residents (e.g., Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Delaware) had small resident populations and were near more populous states with larger numbers of doctor shoppers.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to develop national, state, and county estimates of patients using multiple prescribers to obtain opioids—a risk factor for opioid abuse and overdose death—and the first to explore ecological correlates of multiple prescribing beyond rural/urban locations. An estimated 0.7% of all opioid patients—or one in 145 patients—during 2008 obtained opioid prescriptions from a suspiciously large number of different prescribers, indicative of probable doctor shopping. The majority of patients (84%) saw one or two different physicians and obtained few prescriptions, probably for short-term treatment of pain; about 15% were in a subpopulation of patients who saw an average of three different prescribers during the year, which probably included patients with longer-term treatment needs and/or more complex conditions. We found wide variation among states and even wider variation among counties in prevalence of probable doctor shoppers, both as a percentage of all county residents and of all opioid patients. The prevalence of opioid patients in the county was the strongest predictor of shopper prevalence in counties, accounting for approximately 30% of the observed inter-county variation. Another 30% was accounted for by a small number of other ecological attributes, including measures of healthcare utilization, the racial/ethnic makeup of the counties’ resident population, and measures related to residents’ income and poverty levels.

These findings of shopper prevalence are generally consistent with other studies. Another study of the same large IMS sample, which did not attempt to derive national or subnational estimates, used a different method but estimated that 0.3% of opioid patients nationwide were doctor shoppers.43 Other studies limited to data from single state prescription monitoring systems have reported estimates of shoppers ranging from 0.2% to 12.8% of all opioid patients, depending upon the state and definition of shopping used.41,47 Most used professional judgment to define a threshold number of different physicians and/or pharmacies that seems excessive, and counted patients who exceeded that threshold. A systematic review of 67 studies of pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy—a small subset of all opioid patients who probably fall in the latent subpopulation comprising about 15% of all opioid patients—calculated that 0.2% abused opioids or became addicted and that 12% developed aberrant drug-related behaviors.48

We estimate that doctor shopper prevalence in a county was approximately proportional to the level of opioid prescribing for therapeutic use in that county, which is consistent with studies reporting strong correlations between opioid exposure and prevalence of abuse.49,50 However, we cannot infer from these data that any patient’s odds risk of beginning opioid therapy and escalating to doctor shopping is one in 143 because these rates are attributes of counties rather than of patients. Our findings could be produced if every patient having a legitimate need for opioid treatment did not abuse the drugs and a small number of persons seeking opioids for misuse simply turned to doctor shopping as a relatively low-risk method of obtaining them. Both legitimate opioid patients and doctor shoppers would be more prevalent in areas where physicians, hospitals, and emergency departments were more plentiful. Because we lacked patients’ addresses and located them according to their prescribers’ professional address, our count of opioid patients indicates where their prescribers were rather than where patients lived. This may account for the higher rates of opioid patients in urban areas if patients traveled to urban centers where physicians were more prevalent. Similarly, doctor shoppers may have been more prevalent in areas where physicians and healthcare facilities were more plentiful simply because the opportunities for obtaining multiple prescriptions were greater. We found that probable doctor shoppers did travel; an estimated 30% of them crossed state lines to purchase as least one of their prescribed opioids during 2008. Another study found that almost 20% of “heavy” doctor shoppers but only 4% of non-shoppers obtained prescriptions in more than one state, and that the median distance that heavy shoppers traveled between pharmacy locations was 200 miles, compared with 0 miles for non-shoppers.51

It is therefore important to recognize that our findings pertain to the ecology of the places where doctor shopping and prescribing occurred and not where patients and shoppers lived. If such a large proportion of shoppers crossed state lines to obtain prescriptions, an even larger proportion probably crossed county lines to obtain them. The attributes of their counties of residence may therefore differ greatly from the counties where they obtain their prescriptions.

Several matters deserve further examination. Our study finds that prevalence of both opioid prescribing and doctor shopping in counties is highly correlated, but the causal relationship is unclear. Does this reflect the escalation of opioid therapy into abuse for a small but predictable fraction of patients or the greater availability in certain places of prescribers to be deceived by persons who never needed treatment for pain but sought drugs for recreational or other nonmedical use? Both types of patients certainly exist, but we have no estimates of their relative prevalence in the USA or in different geographical locations. Clarifying this requires longitudinal analysis of patient-level prescription and/or medical records coupled with geographic analyses.

Nor do we know how many opioids are diverted to nonmedical use from each of the various sources. Doctor shopping is but one channel. Other means include obtaining prescriptions from unethical or negligent prescribers or pharmacists; forged prescriptions; theft from pharmacies, healthcare providers, or home medicine cabinets; smuggling; rogue Internet sites; and prescribing excessive amounts when patients need only short-term pain relief. Surveys of households find nonmedical users reporting that the majority of prescription drugs so used was provided by a friend or relative and was prescribed by one doctor; only about 3–4% reported getting them from more than one doctor.24 Users at the end of a distribution chain may not have accurate knowledge of the ultimate source of the drugs, however. Four-fifths of household survey respondents asked similar questions in 2003 about their source of marijuana reported getting it from a friend, but as there were no legal sources that year, all must have been obtained from illegal dealers.52 Although we do not know the relative contribution of doctor shopping to the illicit market, the estimated numbers of prescriptions and amounts of drugs so diverted were large: 4.3 million prescriptions in 2008 containing 11.2 million grams of opioids.

Preventing doctor shopping

Both doctor shopping and well-meaning but dangerously uncoordinated care by multiple prescribers exist in the USA for several reasons. Prescribers often lack adequate information about patients’ previous care and prescription histories. Absent universal electronic medical records, most physicians rely on the records of their own practice networks and what patients tell them about their care. Patients’ intent on obtaining drugs can exploit this situation by feigning conditions and not telling physicians that they have gotten similar prescriptions elsewhere. By going to different pharmacies to fill their prescriptions, they can avoid raising pharmacists’ suspicions. Insurers receive claims data from all pharmacies and can detect suspicious purchasing behavior, but patients can evade detection by paying both prescribers and pharmacies with cash. Forty percent of those we estimated to be probable doctor shoppers paid cash for at least one opioid purchase.

In the absence of universally available electronic medical records, most state governments have established prescription drug monitoring programs (PMPs) to support safe prescribing.53 Laws in these states require pharmacies to report all sales of specified scheduled drugs in the state, regardless of the method of payment, but not all states require reporting sales of all scheduled drugs. Moreover, PMPs only collect information about prescriptions dispensed in their states. Because shoppers are able to evade detection by PMPs in their state of residence by getting opioids in other states, initiatives are under way to develop data sharing among several state PMPs, and the American College of Physicians has called for the creation of a nationwide PMP.54,55

These PMPs enable registered physicians to check patient records, but this still requires time—a scarce resource for primary care and emergency department physicians, who are most likely to encounter shoppers. Few active prescribers were registered users as of 2010 —between 5% and 39%, depending upon the state.54 That such a small percentage of patients obtaining opioid prescriptions are shoppers may reinforce reluctance to spend time checking PMPs about their patients. Three states (Kentucky, Tennessee, and New York) now require prescribers to check the PMP database when initiating opioid treatment of patients and at various other points, which has dramatically increased the number of inquiries and decreased the numbers of patients receiving prescriptions from several different prescribers.56

Another strategy for curbing suspected shoppers is to search PMP prescription data to identify patients whose purchasing behavior suggests doctor shopping (or badly coordinated care) and then notifying all the patients’ prescribers and pharmacists. Insurers and pharmacy chains are also analyzing prescription data and instituting various procedures to alert providers, limit reimbursements, or to otherwise cause closer reviews of opioid prescribing.57–60

Ultimately, because doctors are the source of most diverted opioids, the most effective approach to preventing abuse will be to strengthen prescribing practices. This includes improving technologies to integrate reviews of prescription histories and alerts into physicians’ practices, and increased use of various tools by prescribers to minimize risks of abuse and maximize effective treatment. These include using addiction risk assessments, treatment agreements, referral criteria, and monitoring adherence to treatment by means of urine testing.61,62

Limitations of the study

There are several limitations to both our estimates of opioid prescribing and of doctor shoppers. (i) Although our sample is large, it is not a random representative sample of pharmacies. Some counties had no reporting pharmacies. Opioids dispensed by clinics, treatment facilities, hospitals, and nursing homes were not included (but these dispensed only 14% of all opioids that year63). (ii) Identification of probable shoppers turned on the numbers of different prescribers and may have misidentified some patients who saw different physicians in the same practice. (iii) Our estimates assumed that patients’ rates of using new physicians to obtain prescriptions were Poisson distributed. Under any other distribution, the estimated number of shoppers was smaller than we estimate here. Our estimates should be considered approximate upper bounds.

KEY POINTS.

An estimated 0.7% of opioid patients nationwide obtained an estimated 4.3 million prescriptions from large numbers of different prescribers, indicative of doctor shopping or dangerously uncoordinated care that puts patients at risk of abuse, dependence, and death.

Prevalence of probable doctor shopping varied widely among states and even more widely among counties.

County rates of probable doctor shopping were correlated strongly with rates of therapeutic use of opioids and with numbers of prescribers in counties.

Approximately 30% of doctor shoppers obtained prescriptions in multiple states, thereby reducing the surveillance capabilities of state monitoring programs.

More effective prevention of doctor shopping and uncoordinated care will require improved availability of patients’ prescription histories and more frequent use of practices to minimize risks of abuse, dependence, and death.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Izrael, Abt Associates, for his work to construct the analytic dataset. Sarah Shoemaker, Ph.D., Pharm.D., R.Ph, and Jessica Levin, both of Abt Associates, provided advice in classifying drugs for this dataset.

This study was supported by grant RC2 DA028920 awarded to Abt Associates Inc. by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIH/NIDA). NIH/NIDA had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or decision about publication. None of the authors has any institutional or personal conflicts of interest. Both authors had full access to the data in the study and are responsible for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. Abt Associates’ Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Prescription LRx Data, 2008, was obtained by Abt Associates under license from IMS Health, Inc.; all rights reserved. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views or policies of Abt Associates Inc., NIH, NIDA, or IMS Health, Inc. or any of its affiliated or subsidiary entities.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The Abt Associates Institutional Review Board approved this study. Consent of subjects was not required because the data obtained for analysis had been de-identified.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC grand rounds: prescription drug overdoses—a U.S. epidemic. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:10–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander GC, Kruszewski SP, Webster DW. Rethinking opioid prescribing to protect patient safety and public health. JAMA. 2012;308:1865–1866. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L-H, Hedegaard H, Warner M. QuickStats: number of deaths from poisoning, drug poisoning, and drug poisoning involving opioid analgesics—United States, 1999–2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:234. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM, Anderson RN, Miniño AM. NCHS data brief. Vol. 81. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2011. [accessed 10 November 2013]. Drug poisoning deaths in the United States, 1980–2008. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db81.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. DAWN Series: D-24. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2003. [12 November 2013]. Emergency department trends from the Drug Abuse Warning Network, final estimates 1995–2002. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/driverrprt/dawn2k2/edfinal2k2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The DAWN report: highlights of the 2011 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) findings on drug-related emergency department visits. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2013. [20 November 2013]. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DAWN127/sr127-DAWN-highlights.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) highlights—2007 National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2009. [13 November 2013]. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/TEDS2k7highlights/TEDSHigh2k7.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2000–2010. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. DASIS. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2012. [11 November 2013]. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k12/TEDS2010N/TEDS2010NWeb.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dijkstra A, Hak E, Janssen F. A systematic review of the application of spatial analysis in pharmacoepidemiologic research. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23:504–514. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.05.015. S1047-2797(13)00153-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The NSDUH report: state estimates of nonmedical use of prescription pain relievers. Rockville, MD: 2013. [May 5, 2013]. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k12/NSDUH115/sr115-nonmedical-use-pain-relievers.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossen LM, Khan D, Warner M. Hot spots in mortality from drug poisoning in the United States, 2007–2009. Health Place. 2014;26:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.11.005. S1353-8292(13)00155-X [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith MY, Irish W, Wang J, Haddox JD, Dart RC. Detecting signals of opioid analgesic abuse: application of a spatial mixed effect Poisson regression model using data from a network of poison control centers. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:1050–1059. doi: 10.1002/pds.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Rockville, MD: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office of National Drug Control Policy. ADAM II: 2011 annual report, Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring Program II. Office of National Drug Control Policy, Executive Office of the President; Washington, D.C: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brownstein JS, Green TC, Cassidy TA, Butler SF. Geographic information systems and pharmacoepidemiology: using spatial cluster detection to monitor local patterns of prescription opioid abuse. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 19:627–637. doi: 10.1002/pds.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cerda M, Ransome Y, Keyes KM, et al. Prescription opioid mortality trends in New York City, 1990–2006: examining the emergence of an epidemic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.027. S0376-8716(13)00003-3 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes T, Juurlink D, Moineddin R, et al. Geographical variation in opioid prescribing and opioid-related mortality in Ontario. Healthc Q. 2011;14:22–24. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2011.22153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keyes KM, Cerda M, Brady JE, Havens JR, Galea S. Understanding the rural–urban differences in nonmedical prescription opioid use and abuse in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e52–e59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Havens JR, Walker R, Leukefeld CG. Prevalence of opioid analgesic injection among rural nonmedical opioid analgesic users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.008. S0376-8716(06)00285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leukefeld CG, Narevic E, Hiller ML, et al. Alcohol and drug use among rural and urban incarcerated substance abusers. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol. 2002;46:715–728. doi: 10.1177/0306624X02238164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, et al. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008;300:2613–2620. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green TC, Grau LE, Carver HW, Kinzly M, Heimer R. Epidemiologic trends and geographic patterns of fatal opioid intoxications in Connecticut, USA: 1997–2007. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;115:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.007. S0376-8716(10)00382-0 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilsey BL, Fishman SM, Gilson AM, et al. An analysis of the number of multiple prescribers for opioids utilizing data from the California Prescription Monitoring Program. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:1262–1268. doi: 10.1002/pds.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: 2012. [20 November 2016]. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/2k11results/nsduhresults2011.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce TG. Gen-X junkie: ethnographic research with young White heroin users in Washington, DC. Subst Use Misuse. 1999;34:2095–2114. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rigg KK, Kurtz SP, Surratt HL. Patterns of prescription medication diversion among drug dealers. Drugs (Abingdon Engl) 2012;19:144–155. doi: 10.3109/09687637.2011.631197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattison AM, Ross MW, Wolfson T, Franklin D. Circuit party attendance, club drug use, and unsafe sex in gay men. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00060-8. S0899-3289(01)00060-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller M. History and epidemiology of amphetamine abuse in the United States. In: Klee H, editor. Amphetamine Misuse: International Perspectives on Current Trends. Harwood Academic Publishers; Amsterdam: 1997. pp. 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtis R. Crack, cocaine and heroin: drug eras in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, 1960–2000. Addiction Res Theor. 2003;11:47–63. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourgeois P. In search of Horatio Alger: culture and ideology in the crack economy. In: Reinarman C, Levine HG, editors. Crack in America. University of California Press; Berkeley, California: 1997. pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald DC, Carlson K, Izrael D. Geographic variation in opioid prescribing in the U. S J Pain. 2012;13:988–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White AG, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M, Tang J, Katz NP. Analytic models to identify patients at risk for prescription opioid abuse. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:897–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paulozzi LJ, Kilbourne EM, Shah NG, et al. A history of being prescribed controlled substances and risk of drug overdose death. Pain Med. 2012;13:87–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peirce GL, Smith MJ, Abate MA, Halverson J. Doctor and pharmacy shopping for controlled substances. Med Care. 2012;50:494–500. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824ebd81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baumblatt JAG, Wiedeman C, Dunn JR, Schaffner W, Paulozzi LJ, Jones TF. High-risk use by patients prescribed opioids for pain and its role in overdose deaths. JAMA Intern Med. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Von Korff M, Dunn KM. Chronic pain reconsidered. Pain. 2008;138:267–276. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.12.010. S0304-3959(07)00750-6 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eastern Metropolitan Region Palliative Care Consortium Clinical Working Party; Consortium EMRPC, editor. Opioid conversion ratios—guide to practice. Victoria, Australia: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paulozzi LJ, Jones CM, Mack KA, Rudd RA. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services. Area Resource File (ARF) Access System 2008. Health Resources and Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2008. http://arf.hrsa.gov/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katz N, Panas L, Kim M, et al. Usefulness of prescription monitoring programs for surveillance—analysis of Schedule II opioid prescription data in Massachusetts, 1996–2006. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:115–123. doi: 10.1002/pds.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilsey BL, Fishman SM, Gilson AM, et al. Profiling multiple provider prescribing of opioids, benzodiazepines, stimulants, and anorectics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cepeda M, Fife D, Mastrogiovanni G, Henderson CS. Assessing opioid shopping behaviour: a large cohort study from a medication dispensing database in the US. Drug Saf. 2012;35:325–334. doi: 10.2165/11596600-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cepeda M, Fife D, Mastrogiovanni G, Henderson CS. Opioid shopping behavior: how often, how soon, which drugs, and what payment method. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;53:112–117. doi: 10.1177/0091270012436561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deb PFMM. Stata module to estimate finite mixture models. [Accessed 10 February, 2012];Econ Papers. 2012 http://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s456895.htm.

- 45.McLachlan G, Peel D. Finite Mixture Models. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McDonald DC, Carlson KE. Estimating the prevalence of opioid diversion by “doctor shoppers” in the United States. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katz N, Panas L, Kim M, et al. Usefulness of prescription monitoring programs for surveillance—analysis of Schedule II opioid prescription data in Massachusetts, 1996–2006. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19:115–123. doi: 10.1002/pds.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis J, Rosomoff HL, Rosomoff RS. What percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med. 2008;9:444–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schneider MF, Bailey JE, Cicero TJ, et al. Integrating nine prescription opioid analgesics and/or four signal detection systems to summarize statewide prescription drug abuse in the United States in 2007. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:778–790. doi: 10.1002/pds.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cicero TJ, Surratt H, Inciardi JA, Munoz A. Relationship between therapeutic use and abuse of opioid analgesics in rural, suburban, and urban locations in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:827–840. doi: 10.1002/pds.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cepeda MS, Fife D, Yuan Y, Mastrogiovanni G. Distance traveled and frequency of interstate opioid dispensing in opioid shoppers and nonshoppers. J Pain. 2013;14:1158–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.04.014. S1526-5900(13)00992-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. NSDUH Series H-25. Rockville, MD: 2004. Results from the 2003 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alliance of States with Prescription Monitoring Programs. [Accessed 14 August 2013];Status of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) 2012 http://www.pmpalliance.org/pdf/pmp_status_map_2012.pdf.

- 54.The MITRE Corporation. Enhancing access to Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs using health information technology: work group recommendations. McLean, VA: The MITRE Corporation; Aug 17, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kirschner N, Ginsburg J, Sulmasy LS. Prescription drug abuse: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:198. doi: 10.7326/M13-2209. 1788221 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Center of Excellence. Mandating PDMP Participation by Medical Providers: Current Status and Experience in Selected States. Brandeis University; Waltham, MA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tudor CG. Memorandum: Medicare Part D Overutilization Monitoring System. Center for Medicare, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Department of Health & Human Services; Baltimore: Jul 5, 2013. [1 December 2013]. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/HPMS-memo-Medicare-Part-D-Overutilization-Monitoring-System-07-05-13-.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts. [Accessed May 3, 2014, 2014];New quality and safety measures in opioid management, Effective. 2012 Jul 1; https://www.bluecrossma.com/bluelinks-for-employers/whats-new/special-announcements/opioid-man-agement.html.

- 59.Trafton J, Martins S, Michel M, et al. Evaluation of the acceptability and usability of a decision support system to encourage safe and effective use of opioid therapy for chronic, noncancer pain by primary care providers. Pain Med. 2010;11:575–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00818.x. PME818 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wohl J. CVS cuts access to opioid pain-killers for suspect doctors. Reuters. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manchikanti L, Atluri S, Trescot AM, Giordano J. Monitoring opioid adherence in chronic pain patients: tools, techniques, and utility. Pain Physician. 2008;11:S155–S180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:38–47. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-160-1-201401070-00732. 1767856 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Drug Enforcement Administration. Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS) Retail Summary Reports. Office of Diversion Control; 2008–2011. [Google Scholar]