STRUCTURED ABSTRACT

Objective

To evaluate the impact of health insurance expansion on racial disparities in severity of peripheral arterial disease.

Summary Background Data

Lack of insurance and non-white race are associated with increased severity, increased amputation rates, and decreased revascularization rates in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD). Little is known about how expanded insurance coverage affects disparities in presentation with and management of PAD. The 2006 Massachusetts health reform expanded coverage to 98% of residents and provided the framework for the Affordable Care Act.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of non-elderly, white and non-white patients admitted with PAD in Massachusetts (MA) and four control states. Risk-adjusted difference-in-difference models were used to evaluate changes in probability of presenting with severe disease. Multivariable linear regression models evaluated disparities in disease severity before and after the 2006 health insurance expansion.

Results

Prior to the 2006 MA insurance expansion, non-white patients in both MA and control states had a 12–13 percentage-point higher probability of presenting with severe disease (P<0.001) than white patients. After the expansion, measured disparities in disease severity by patient race were no longer statistically significant in Massachusetts (+3.0 percentage-point difference, P=0.385) while disparities persisted in control states (+10.0 percentage-point difference, P<0.001). Overall, non-white patients in MA had an 11.2 percentage-point decreased probability of severe PAD (P=0.042) relative to concurrent trends in control states.

Conclusions

The 2006 Massachusetts insurance expansion was associated with a decreased probability of patients presenting with severe PAD and resolution of measured racial disparities in severe PAD in MA.

Introduction

Racial and socioeconomic disparities in treatment and outcomes persist across medical disciplines, including vascular disease. Lack of insurance coverage and non-white race have been shown to be associated with increased severity of peripheral artery disease, decreased rates of revascularization, and increased rates of amputation.1–6 Studies have suggested that lack of insurance and poor access to care contribute to delayed presentation with more advanced vascular disease and tissue loss, limiting opportunities for limb salvage. Despite two decades of improvement in severity of vascular disease and decreased utilization of amputation population-wide, disparities in presentation with and management of vascular pathology persist by both insurance status and patient race.7–10

Many have looked to inequities in insurance coverage as a key driver of racial disparities in health care. The 2006 Massachusetts health care reform provides a unique natural experiment to evaluate the impact of health insurance expansion on disparities in vascular surgery. Nearly all provisions within the legislation were aimed at increasing access to insurance coverage through mechanisms that included the expansion of Medicaid, creation of a new subsidized insurance program for those ineligible for Medicaid, and expanding young adult eligibility on parental plans until age 26.11 The law also provided the basic framework for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which has the potential of adding insurance coverage to more than 16-million Americans.12

Since implementation of the 2006 Reform, Massachusetts has seen increased insurance coverage to about 98% of its residents.13 Trends in insurance coverage for residents of Massachusetts throughout the study period can be found in the Supplement (eFigure1). Non-white residents saw particularly strong gains in insurance coverage with uninsurance rates decreasing in the years following reform by 44% and 77% for Hispanic and black citizens, respectively. However, questions remain as to whether increased insurance coverage will translate into increased access to or quality of medical care for non-white patients, especially given myriad of factors associated with racial disparities.14–17

Prior studies of racial disparities in vascular disease have speculated that uninsured patients – disproportionately minority – might delay seeking care out of financial concerns or disenfranchisement from the health system, only to present later with more advanced disease. If these assumptions about insurance coverage and access to care are true, the question remains whether increased coverage across populations actually decreases delays in seeking care for pathologies such as lower extremity limb ischemia.

With this study, we test the hypothesis that increased insurance coverage in Massachusetts would be associated with decreased probability of patient presentation with severe vascular disease, instead presenting with earlier symptoms of disease prior to progression to tissue loss. We also performed secondary analyses to evaluate for associated changes in revascularization procedures and lower extremity amputation after admission for PAD. Given significant gains in insurance coverage for minority residents, we hypothesized that racial disparities in disease severity and management would decrease after the 2006 health reform.

METHODS

Study Design & Data

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Hospital Cost and Utilization Project State Inpatient Databases (SID) for Massachusetts, New Jersey, Arizona, Florida, and Maryland spanning January 1, 2001 through December, 31 2010. Control states were selected based on completeness of data, similar availability of surgical services, and similar distribution of racial minorities within the government-subsidized/uninsured population.18,19 The SID are administrative data that capture approximately 98% of all discharges from all hospitals across respective states each year. Data are collected and maintained by public-private partnerships, supported by the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

We included all admissions of non-disabled, non-elderly, white and non-white (black and Hispanic) adult patients with no insurance, Medicaid coverage, or the newly created Commonwealth Care insurance, admitted with symptomatic lower extremity arterial disease (claudication, rest pain, ulcer, or gangrene). This cohort represents the primary population impacted by the 2006 health reform in Massachusetts that predominantly led to increased enrollment in either Medicaid or Commonwealth Care coverage.13 Public data suggest little change in the proportion of newly insured resident enrolling in either private insurance plans or Medicare.20 Therefore patients with private or Medicare insurance coverage were excluded from this evaluation. However, separate sensitivity analyses were also performed to evaluate for differential trends in outcomes prior to 2006 as well as racial disparities within the privately insured population between the ages of 18 and 65 years. Patients aged less than 18 years or greater than 65 years were also excluded as coverage for these individuals were largely not affected by the insurance expansion.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of interest was severity of disease at presentation. Using ICD-9 diagnosis codes, severe disease was defined as patient presentation with tissue loss, namely ulceration, tissue necrosis or gangrene (ICD-9-CM 44.23 and 44.24, respectively), while non-severe presentation was classified if the patient presented with claudication or rest pain (ICD-9-CM 44.21 and 44.22, respectively). These ICD-9 codes have been previously used to evaluate severity of lower extremity arterial disease.9,21 Secondary outcome measures included probability of receiving revascularization procedures and probability of amputation. The designation of revascularization included all open bypass procedures as well as endovascular interventions (ICD-9-CM 00.40–00.48, 00.60, 00.61, 38.00–38.18, 38.30, 38.40, 38.48, 39.25, 39.29, 39.56–39.59, 39.71, 39.78, 39.79, 39.90, 88.48). All amputations of bony structures from the level of hip disarticulation through toe amputation were considered an amputation (ICD-9-CM 84.10 – 84.18). Additional outcomes included length of inpatient hospitalization and cost of care. Length of inpatient hospitalization was also determined using pre-defined length of stay (LOS) variable within the SID. Costs were calculated using HCUP cost-to-charge ratios as previously described elsewhere with all costs inflation-adjusted to 2012 dollars.22–24

Risk Adjustments

Our analyses included adjustment for confounding factors at the patient, hospital, and state level. Multivariate models controlled for age, sex, comorbidities using the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index25, admission type, and patient’s home location, and hospital fixed effects. Admission type was broken down by emergent, urgent, routine, or other/not otherwise specified. Patient location was defined using the patient’s home Core Based Statistical Area (CBSA) as defined by the Office of Management and Budget 2003 Metropolitan definitions. Hospital level confounding was controlled for using hospital fixed effects by individual hospital identifiers. For each model, we used Stata’s cluster-correlated robust estimate of variance with the vce(cluster clustvar) option to account for clustering with hospitals.26 Secular trends were defined on a quarterly basis using a continuous time variable starting at the first quarter of 2001 and ending with the fourth quarter of 2010.

The primary factors examined included intervention group (Massachusetts vs. Control States), patient race (Non-White vs. White), and pre- or post-reform time of discharge. The pre-reform period was defined as any admission before the third quarter of 2006, the time the legislation was passed, and post-reform was defined as any discharge after the fourth quarter of 2007. The time period between 2006 quarter three and 2008 quarter one were excluded as this was the period of implementation spanning initial signing of legislation and full implementation of the individual mandate requiring all residents to carry insurance. Previous studies have also shown the most significant uptake in insurance coverage occurred after this mandate went into effect in January 2008.27 However, sensitivity analyses including this period between 2006 and 2008 did not change our results.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics between Massachusetts and control states were compared using student t-tests, chi-squared, and non-parametric tests. We used difference-in-differences models to evaluate the differential change in outcomes in MA after reform relative to concurrent trends in control states.28–31 These models identify differential changes in outcomes in groups exposed to a policy change as compared to the control group not exposed to the policy change. To evaluate for a differential change in outcomes for patients in MA after reform relative to control states, we used an interaction term between MA and the post-reform indicator variable. The subsequent coefficient (the difference-in-differences estimator) represents the independent change in the outcome associated with the 2006 intervention for all patients, controlling for patient race and other covariates. To look specifically at changes by patient race, we created a three-term interaction variable between MA, post-reform, and non-white race. This “triple-difference” estimator represents the independent impact of the 2006 Massachusetts reform on non-white patients in Massachusetts. In linear models, these coefficients represent the absolute change in the probability of outcomes attributable to the insurance expansion.

Multivariate Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression models were fit to evaluate for disparities by patient race before and after the 2006 reform in respective intervention groups. These models produce a difference in the probability of respective outcomes, representing an absolute difference in probability attributable to patient race. We chose to use linear models to predict absolute changes in the probability of the outcome variable associated with the insurance coverage expansion in Massachusetts. Unlike logit or probit models, linear models do not require transformation of the data along, for example, a logit distribution.32 In sensitivity analyses, however, we also fit the data to logistic models, which did not change the interpretation of our results. This study was deemed exempt from IRB review. Data were analyzed using Stata 12.1. Results were considered significant if P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

In total, we included 20,295 admissions of non-elderly white and non-white patients with no insurance or government subsidized coverage who were admitted with lower extremity PAD in Massachusetts (n= 3,239) and control states (n=17,056). Both Massachusetts and control states had similar rates of admissions for PAD throughout the study period, ranging from 2–3 admissions per 10,000 individuals with no differential change in rate of admissions after the 2006 insurance reform. Overall, Massachusetts admissions were more likely to be for male patients at a large, not-for-profit urban hospital. They were less likely to be non-white and admitted emergently. Patient age, comorbidity indices, and rates of routine admissions were comparable between the groups (Table 1). Breakdown of demographic variables by patient race can be seen in eTable 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Massachusetts N=3,239 |

Control States N=17,056 |

|

|---|---|---|

| State n (%) | ||

| Massachusetts | 3,239 (100) | --- |

| Arizona | --- | 2,537 (14.9) |

| Florida | --- | 9,170 (53.8) |

| Maryland | --- | 2,922 (17.1) |

| New Jersey | --- | 2,427 (14.2) |

|

| ||

| Age years (std) | 55.1 (6.8) | 54.7(7.1) |

|

| ||

| Male n (%) | 2,095 (64.7) | 10,150 (59.51) |

|

| ||

| Non-white n (%) | 807 (24.9) | 7,261 (42.6) |

|

| ||

| Insured Pre-Reform n (%) | 1,401 (87.5) | 5,762 (71.9) |

| Insured Post-Reform n (%) | 1,134 (95.7) | 4,616 (71.6) |

|

| ||

| Elixhauser Index mean score (std) | 2.9 (1.6) | 3.1 (1.6) |

|

| ||

| Patient Home Location n (%) | ||

| Non-CBSA Area | 17 (0.5) | 431 (2.5) |

| Micropolitan Area | 16 (0.5) | 703 (4.1) |

| Metropolitan Area | 2,919 (90.1) | 14,504 (85.0) |

| Other | 287 (8.9) | 1,418 (8.3) |

|

| ||

| Hospital Type n (%) | ||

| NFP, Urban, <100 | 43 (1.3) | 160 (0.9) |

| NFP, Urban 100–299 | 785 (24.2) | 3,697 (21.7) |

| NFP, Urban, ≥ 300 | 2,254 (69.6) | 9,567 (56.2) |

|

| ||

| Admission Type n (%) | ||

| Emergency | 1,261 (38.9) | 8,758 (51.4) |

| Urgent | 938 (29.0) | 2,713 (15.9) |

| Elective | 1,039 (32.1) | 5,525 (32.4) |

CBSA – Core Based Statistical Area

NFP – Not-for-profit hospital

Impact of Reform on All Uninsured/Government Subsidized Patients

Prior to the 2006 reform, 824 (51.1%) admissions in Massachusetts and 4,792 (59.8%) admissions in control states were admitted with severe disease. After the reform, 468 (39.5%) of admissions in Massachusetts and 3,454 (53.6%) of admissions in control states were admitted with severe disease. In adjusted analysis, Massachusetts patients had a 4.2 percentage-point decrease (95% CI −10.8 to 2.4, P=0.207) in the probability of admissions for severe disease after health care reform relative to control states (Table 2). Patients in Massachusetts underwent revascularization procedures during 815 (50.1%) admissions compared to 3,390 (42.3%) admissions within control states prior to 2006. Before expansion, 402 (24.9%) admissions in Massachusetts and 2,418 (30.2%) admissions control state were associated with an amputation during their admission.

Table 2.

Changes in presentation and management of all uninsured or government-subsidized patients after the 2006 Massachusetts Health Reform

| Massachusetts | Control | Difference-in-Difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Diff | Pre | Post | Diff | Unadjusted | Adjusted* (CI, P-value) | |

| Probability of Severe Disease at Presentation | 51.1 | 39.5 | −11.6 | 59.8 | 53.6 | −6.2 | −5.4 | −4.2 ( −10.8 – 2.4, P=0.207) |

|

| ||||||||

| Probability of Revascularization | 50.6 | 62.8 | + 12.2 | 42.3 | 54.2 | +11.9 | +0.3 | −1.6 (−6.2 – 3.0, P=0.504) |

|

| ||||||||

| Probability of Amputation | 24.9 | 14.0 | −10.9 | 30.2 | 23.8 | −6.4 | −4.5 | −4.7 (−8.4 – −1.1, P =0.011) |

Controlling for patient and hospital level confounders as well as secular trends. Sensitivity analysis showed no pre-intervention differential changes in probability of outcomes between respective groups.

While the overall rate of revascularization procedures increased in all states after reform, there was no differential change in revascularization rates during admissions in Massachusetts after expansion relative to control states. However, the 2006 insurance expansion was associated with a 4.7 percentage-point decreased probability (95% CI −8.4 to −1.1, P=0.011) of receiving an amputation in Massachusetts as compared with control states.

Sensitivity analyses prior to the 2006 reform revealed no differential trends in admissions with severe disease or receipt of revascularization or amputation within Massachusetts relative to control states. Additional sensitivity analyses of admissions of privately-insured patients in Massachusetts showed no differential changes in outcomes for non-white patients after reform relative to white patients, including in the probability of presenting with severe disease (−1.33 percentage-points, 95% CI −11.32 to 8.67, P=0.791), probability of receiving revascularization (−2.57 percentage-points, 95% CI −11.08 to 5.94, P=0.549), or probability of undergoing amputation during admission (−1.13 percentage-points, 95% CI −8.36 to 6.10, P=0.755).

Impact on Non-White Patients and Racial Disparities

Disease Severity

Prior to 2006, approximately 60–70% of all admissions of non-white patients in Massachusetts and control states were for severe diseases (Figure 1). Compared to white patients, non-white patients had a 13.0 percentage-point higher probability (95% CI 6.9 to 19.1, P<0.001) of admission with severe disease in Massachusetts and a 12.1 percentage-point higher probability (95% CI 9.4 to 14.8, P<0.001) in control states. After reform, non-white patients in Massachusetts had a smaller and statistically insignificant 3.0 percentage-point greater (95% CI −3.9 to 10.0, P=0.385) probability of admission with severe disease relative to white patients. Meanwhile, disparities by patient race persisted in control states with non-white patients having a 10.0 percentage-point greater (95% CI 6.6 to 13.4, P<0.001) likelihood of severe PAD at admission. Controlling for secular trends and interstate variability, the 2006 health reform was associated with an 11.1 percentage-point decrease (95% CI − 22.0 to − 0.4, P=0.042) in the probability of admission with severe disease for non-white patients in Massachusetts (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted trends in a) severe ischemia, b) revascularization procedures, and c) amputations for uninsured or government-subsidized non-white patients

* 2006 Massachusetts insurance expansion

Table 3.

Changes in presentation and management of non-white patients after the Massachusetts health reform

| Massachusetts | Control | Difference-in-Difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Diff | Pre | Post | Diff | Unadjusted | Adjusted* (CI, P -value) | |

| Probability of Severe Disease at Presentation | 67.7 | 45.2 | −22.5 | 70.8 | 61.7 | −9.1 | −13.4 | −11.2 (−22.0 – −0.4, P=0.042) |

|

| ||||||||

| Probability of Revascularization | 37.9 | 55.9 | +17.9 | 35.9 | 48.2 | 12.4 | +5.6 | +7.3 (−2.6 – 17.2, P=0.150) |

|

| ||||||||

| Probability of Amputation | 36.2 | 18.2 | −18.0 | 39.1 | 29.6 | −9.5 | −8.5 | −3.4 (−10.3 – 3.4, P=0.326) |

Controlling for patient and hospital level confounders as well as secular trends. Sensitivity analysis showed no pre-intervention differential changes in probability outcomes between respective groups.

Revascularization

Before Reform, 36–38% of admissions for non-white patients had an associated revascularization procedure. Non-white patients in Massachusetts had a 6.7 percentage-point lower probability (95% CI −13.4 to 0.0, P=0.051) of receiving a revascularization procedure compared to white patients. Non-white patients in control states were 6.0 percentage-points less likely (95% CI −8.5 to −3.4, P<0.001) to undergo a revascularization procedure compared to white patients. After reform, racial disparities in revascularization procedures were no longer statistically significant in Massachusetts with non-white patients having a 0.1 percentage point lower probability (95% CI −6.6 to 6.4, P=0.982) of revascularization. However, racial disparities persisted in control states where non-white patients still had a 6.0 percentage-point lower (95% CI −8.6 to −3.3, P<0.001) probability of receiving a revascularization procedure. The insurance expansion was associated with a 7.3 percentage-point increased probability (95% CI −2.6 to 17.2, P=0.150) of receiving a revascularization procedure for non-white patients in Massachusetts relative to control.

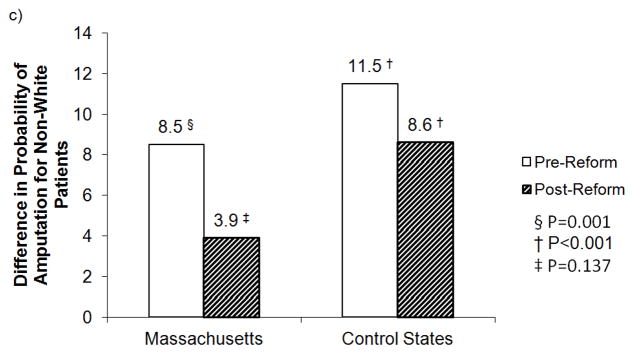

Amputation

Prior to Massachusetts insurance expansion, rates of amputation during admission of non-white patients were between 36% and 39%. Non-white patients in Massachusetts had an 8.5 percentage-point higher probability (95% CI 3.4 to 13.5, P=0.001) of undergoing amputation while non-white patients in control states had an 11.5 percentage-point greater probability (95% CI 9.0 to 14.0, P<0.001) of amputation. After 2006, non-white patients in Massachusetts had a smaller and statistically insignificant 3.9 percentage-point higher probability (95% CI −1.3 to 9.1, P=0.137) of undergoing amputation compared to white patients within MA. Within control states, non-white patients had an 8.6 percentage-point greater probability (P<0.001) of receiving an amputation. The insurance expansion was associated with a 3.4 percentage-point decrease (95% CI −10.3 to 3.4, P=0.326) in the probability of amputation for non-white patients in MA.

Length of Stay and Costs

The 2006 insurance expansion was associated with 1.24 day decreased length of stay (95% CI −2.01 to −0.47, P=0.002) for admissions in Massachusetts relative to control states. After reform in Massachusetts, admission with severe disease was associated with $US 5,099.90 (95% CI 2,096.59 to 8,103.22, P=0.001) added cost relative to patients without severe disease. The added cost associated with severe disease in control states after 2006 was $US 7,687.54 (95% CI 5,952.18 to 9,422.89, P<0.001). Adjusted analyses revealed no differential change in the mean cost of care for uninsured or government-subsidized patients in Massachusetts after the reform relative to control states ($US 229.74, 95% CI −1,703.96 to 2,163.44, P=0.815).

DISCUSSION

Disparities in access to and outcomes of care for lower extremity arterial disease have been well-documented for both non-white and uninsured patients. Here we present evidence that the expansion of insurance coverage in Massachusetts was associated with reduced racial disparities in presentation with severe lower-extremity arterial disease. Similarly, observed racial disparities in revascularization and amputation after admission with PAD were also no longer significant in Massachusetts after reform while they persisted in control states. Difference-indifference estimates revealed a statistically significant association between expanded insurance coverage in Massachusetts and reduced probability of non-white patients presenting with severe PAD.

With no measurable increase in the rates of inpatient surgical procedures for non-white patients, the decrease in disparities in amputation is mostly likely due to decreased severity of vascular disease at the time of presentation. Patients may be admitted with less severe disease because of either earlier presentation or better management of disease in the outpatient setting. Socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals might be more financially vulnerable or more reluctant to seek care without insurance as compared to uninsured white individuals.33

Our findings are consistent with prior studies from Massachusetts. Since the implementation of the Massachusetts reform, newly insured patients have reported improved access to primary care providers, decreased difficulties obtaining specialist care, increased utilization of preventative care, and better management of chronic comorbid conditions.34–38 Previous reports from the state also suggest that measured disparities in overall health status and severity of presentation may indeed decrease as newly insured patients gain access to health systems.39 Multiple studies have suggested increased surgical referrals and decreased disparities in the receipt of certain procedures after expanded insurance coverage.40–45 However, our data do contrast another recent study that found no change in disparities of coronary revascularization procedures after Massachusetts health care reform, although their analysis was limited by short follow-up data ending in September of 2008, only nine months after implementation of mandate requiring insurance coverage.46

The HCUP-SID capture nearly 100% of all inpatient admissions across states but are bound by the limitations of administrative data, including the possibility of coding discrepancies and limited clinical granularity better captured in clinical datasets. However, the ICD-9 codes and administrative datasets have been previously used to evaluate population-wide perspective on severity of vascular disease.9,17 Furthermore, it is unlikely that a sudden unrelated change in coding occurred only for a subset of the Massachusetts population (government-subsidized/self-pay non-white patients) after health reform. There were also considerable differences in baseline characteristics between Massachusetts and control states, including lower percentage of non-white patients and higher utilization of large volume hospitals in Massachusetts. Thus, the findings in Massachusetts may not be generalizable elsewhere in the country. We attempted to account for hospital- and patient-level factors in subsequent analyses, but our findings could represent uncontrolled changes within hospital systems or population dynamics independent of the insurance expansion. One might ask if rates of overall admission for PAD differentially changed in Massachusetts relative to control states, influencing our measured probability of presentation with severe disease. However, our data showed constant rates of admissions for PAD over the duration of our study period in Massachusetts and control states. Therefore the decreased probability of presentation with severe PAD is most likely not explained by increased (potentially unnecessary) admissions of healthier patients, but more likely by decreased severity of disease at the time of admissions. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses of primary outcomes showed no differential trend in outcomes prior to the 2006 reform. Similarly, the insurance expansion did not appear to influence racial disparities in the care of privately-insured patients suggesting against an alternative state-wide change in care delivery besides the reform. With fewer patients uninsured, however, the overall variation in patient care may decrease as patients become more homogeneous in terms of insurance coverage.

Another key limitation of the dataset is the inability to specifically identify the individuals who were uninsured prior to reform and gained insurance coverage with the expansion. We therefore chose to include all admissions before and after reform in which patients were either uninsured or carried a government-subsidized plan, either Medicaid or Commonwealth Care (in Massachusetts). This method provided the best available means to capture a cohort of patients that would be comparable in control states over the same time period. Our sample subsequently included a considerable portion of patients in Massachusetts who had Medicaid coverage both before and after the reform and whose insurance coverage was not explicitly influenced by the law. Yet, we would expect the inclusion of these individuals to attenuate the measured effect rather than amplify any changes associated with the insurance expansion. Given our inability to follow the patients over the study period, some admissions are therefore also likely to be for the same individuals. We were also unable to track long-term outcomes, readmissions, re-intervention, or survival of patients with PAD. Ongoing studies will be needed to assess longitudinal impact of expanded coverage on newly insured populations. However, given the lack of changes in the rates of admissions for patients with PAD, our findings nonetheless provide early, optimistic evidence for improvement in presentation with less severe vascular disease only three years after insurance expansion.

We must also acknowledge that other ecological factors unobserved in the data could have also contributed to these findings. It is reasonable to question whether the dramatic economic changes associated with the 2008 recession influenced our findings. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics suggest that there was not a differential trend in unemployment in Massachusetts compared to control states.47 While crude evaluation may suggest a trend break in patient presentation with severe disease and probability of undergoing amputation prior to full implementation of the legislation, to our knowledge no other broad population-level health policy change or system redesign occurred between 2005 and 2008. It is possible that population and/or provider behavior actually began changing prior to full enactment given considerable publicity and anticipation in the years preceding its implementation.48 Furthermore, all analyses accounted for secular trends in outcomes across the entire study period. Though our analysis does not establish causality, the results suggest a strong association between the 2006 coverage expansion and decreased disparities in PAD within Massachusetts.

In summary, the Massachusetts health reform was associated with decreased probability of non-white patients presenting with severe lower extremity vascular disease. Disparities in the outcomes we observed were no longer statistically significant in Massachusetts after reform while various disparities by patient race persisted in control states. Improvements were seen in outcomes within control states, but the insurance expansion appears to be independently associated with accelerated improvements in patient presentation and outcomes for patients, particularly non-white patients, in Massachusetts. Further data are needed to evaluate ongoing trends within Massachusetts and to assess how similar insurance expansions in other states may influence variation in clinical care for PAD.

Supplementary Material

eFigure 1. Trends in insurance coverage for non-elderly adults in Massachusetts by a) type of coverage and b) patient race

*2006 Massachusetts Health Reform

eTable 1. Patient Demographics by patient race

Figure 2.

Impact of Massachusetts health reform on racial disparities in a) disease severity, b) revascularization, and c) amputation during hospitalization

Acknowledgments

Financial Support

Study supported by Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Bureau of Economic Research (Cambridge, MA) through whom data were made available. Furthermore, databases are maintained through HCUP Data Partners including the Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis, the Arizona Department of Health Services, the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration, the Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission, and the New Jersey Department of Health. This work was also supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (F30-AG039175, to Dr. Song).

Footnotes

Disclosures

No disclosures to report

References

- 1.Giacovelli JK, Egorova N, Nowygrod R, et al. Insurance status predicts access to care and outcomes of vascular disease. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:905–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrissey NJ, Giacovelli J, Egorova N, et al. Disparities in the treatment and outcomes of vascular disease in Hispanic patients. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:971–978. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaranto DJ, Abbas F, Krantz S, et al. An evaluation of gender and racial disparity in the decision to treat surgically arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:1340–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Homan KH, Henke PK, Dimick JB, et al. Racial disparities in the use of revascularization before leg amputation in Medicare patients. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feinglass J, Rucker-Whitaker C, Lindquist L, et al. Racial differences in primary and repeat lower extremity amputation: results from a multihospital study. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:823–829. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams TK, Schneider EM, Black JH, 3rd, et al. Disparities in outcomes for Hispanic patients undergoing endovascular and open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Vasc Surg. 2013;27:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong MS, Beck AW, Nelson PR. Emerging national trends in the management and outcomes of lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feinglass J, Abadin S, Thompson J, et al. A census-based analysis of racial disparities in lower extremity amputation rates in Northern Illinois, 1987–2004. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowe VL, Weaver FA, Lane JS, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in patterns of treatment for acute peripheral arterial disease in the United States, 1998–2006. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:21S–26S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinglass J, Rucker-Whitaker C, Lindquist L, et al. Racial differences in primary and repeat lower extremity amputation: results from a multihospital study. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:823–829. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The General Court of Massachusetts; Apr 12, 2006. [Accessed on Feb 17, 2013]. CHAPTER 58 of the Acts of 2006, AN ACT PROVIDING ACCESS TO AFFORDABLE, QUALITY, ACCOUNTABLE HEALTH CARE. at : http://www.malegislature.gov/Laws/SessionLaws/Acts/2006/Chapter58. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long S. What is the evidence on Health Reform in Massachusetts and How Might the Lessons from Massachusetts Apply to National Health Reform? Urban Institute; Jun, 2010. [Accessed on 1 January 2013]. at: http://www.urban.org/uploadedpdf/412118-massachusetts-national-health-reform.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massachusetts Health Insurance Surveys. Division of Health Care Finance and Policy; Boston, MA: 2010. [Accessed on 1 January 2013]. Health Insurance Coverage in Massachusetts: Results from the 2008–2010. at: http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dhcfp/r/pubs/10/mhis-report-12-2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen LL, Henry AJ. Disparities in Vascular Surgery: Is it biology or Environment. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:36S–41S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henry AJ, Hevelone ND, Belkin M, et al. Socioeconomic and hospital-related predictors of amputation for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Regenbogen SE, Gawande AA, Lipsitz SR, et al. Do differences in hospital and surgeon quality explain racial disparities in lower-extremity vascular amputations? Ann Surg. 2009;250:424–431. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b41d53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng DK, Brotman DJ, Lau B, et al. Insurance status, not race, is associated with mortality after an acute cardiovascular event in Maryland. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1368–1376. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2147-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. [Accessed on 11 October 2012];Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/

- 19. [Accessed at on 1/11/213];US Census Bureau Historic Tables. http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/data/historical/HIB_tables.html.

- 20.Massachusetts household survey on health insurance status, 2007. Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance and Policy; Boston, MA: 2007. [Accessed on 12 December, 2012]. at: http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/researcher/physical-health/health-care-delivery/dhcfp-publications.html#insurance_surveys. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nowygrod R, Egorova N, Greco G, et al. Trends, complications, and mortality in peripheral vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:205–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Livingston EH. Hospital costs associated with bariatric procedures in the United States. Am J Surg. 2005;190:816–820. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fagenholz PJ, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Harris NS, et al. Direct medical costs of acute pancreatitis hospitalizations in the United States. Pancreas. 2007;35:302–307. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3180cac24b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Accessed 24 May 2014];Consumer Price Index Calculator. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

- 25.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers WH. Regress standard errors in clustered samples. Stata Technical Bulletin. 1993;13:19–23. Reprinted in Stata Technical Bulletin Reprints, vol3, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandra A, Gruber J, McKnight R. The importance of the individual mandate—Evidence from Massachusetts. N Eng J Med. 2011;364:293–295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1013067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wooldridge JM. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donald SG, Lang K. Inference with difference-in-differences and other panel data. Rev Econ Stat. 2007;89:221–233. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Athey S, Imbens GW. Identification and inference in nonlinear difference_in_differences models. Econometrica. 2006;74:431–497. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puhani PA. The treatment effect, the cross difference, and the interaction term in nonlinear “difference-in-differences” models. Economics Letters. 2012;115:85–87. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM. Too much ado about two-part models and transformation? Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ. 2004;23:525–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor P, Kochhar R, Fry R, et al. Wealth gaps rise to record highs between whites, blacks, and Hispanics. Pew Research Center; 2011. [Accessed on 11/9/2013]. at: http://ehub29.webhostinghub.com/~busine87/assignments/business_statistics_-_wealt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Long SK, Masi PB. Access and affordability: An update on health reform in Massachusetts, Fall 2008. Health Aff. 2009;28:w578–w587. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Long SK, Stockley K. Sustaining health reform in a recession: An update on Massachusetts as of fall 2009. Health Aff. 2010;29:1234–1241. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, et al. The Oregon health insurance experiment: evidence from the first year. NBER Working Paper No. 17190. Jul; doi: 10.1093/qje/qjs020. 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolstad JT, Kowalski AE. The impact of health care reform on hospital and preventative care: Evidence from Massachusetts. NBER Working Paper No. 16012. 2010 May; [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pande AH, Ross-Degnan D, Zaslavsky AM, Salomon JA. Effects of healthcare reforms on coverage, access, and disparities. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sommers BD, Long SK, Baicker K. Changes in mortality after Massachusetts health care reform: A quasi-experimental study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:585–93. doi: 10.7326/M13-2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Loehrer AP, Song Z, Auchincloss HG, et al. Massachusetts health care reform and reduced racial disparities in minimally invasive surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:1116–1122. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.2750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loehrer AP, Song Z, Auchincloss HG, et al. Influence of health insurance expansion on disparities in the treatment of acute cholecystitis. [Accessed on 03/23/2015];Ann Surg. Mar 18; doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000970. 2105. Epub ahead of print. Available at: http://journals.lww.com/annalsofsurgery/Abstract/publishahead/Influence_of_Health_Insurance_Expansion_on.97449.aspx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Hanchate AD, Lasser KE, Kapoor A, et al. Massachusetts reform and disparities in inpatient care utilization. Med Care. 2012;50:569–577. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824e319f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ellimoottil C, Miller S, Ayanian JZ, et al. Effect of insurance expansion on utiliization of inpatient surgery. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:829–836. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hanchate AD, Kapoor A, Katz JN. Massachusetts health reform and disparities in joint replacement use: difference in differences study. BMJ. 2015;350:h440. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giladi AM, Aliu O, Chung KC. The effect of Medicaid expansion in New York State on use of subspecialty surgical procedures by Medicaid beneficiaries and the uninsured. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:889–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albert MA, Ayanian JZ, Silbaugh TS, et al. Early results of Massachusetts healthcare reform on racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2014;129:2528–2538. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. [Accessed on 2/1/2013];Local Area Unemployment Statistics. at: http://www.bls.gov/lau/#tables.

- 48.Romney M. My plan for Massachusetts health insurance reform. [Accessed on 3/19/2015];The Boston Globe. 2004 Nov 21; at: http://www.bostonglobe.com/lifestyle/health-wellness/2004/11/24/plan-for-massachusetts-health-insurance-reform/d1I1xFpnfLcQ8Ipz4nCdpJ/story.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure 1. Trends in insurance coverage for non-elderly adults in Massachusetts by a) type of coverage and b) patient race

*2006 Massachusetts Health Reform

eTable 1. Patient Demographics by patient race