Abstract

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors represent today's treatment of choice in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is regarded as salvage therapy. This prospective randomized CML-study IIIA recruited 669 patients with newly diagnosed CML between July 1997 and January 2004 from 143 centers. Of these, 427 patients were considered eligible for HSCT and were randomized by availability of a matched family donor between primary HSCT (group A; N=166 patients) and best available drug treatment (group B; N=261). Primary end point was long-term survival. Survival probabilities were not different between groups A and B (10-year survival: 0.76 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.69–0.82) vs 0.69 (95% CI: 0.61–0.76)), but influenced by disease and transplant risk. Patients with a low transplant risk showed superior survival compared with patients with high- (P<0.001) and non-high-risk disease (P=0.047) in group B; after entering blast crisis, survival was not different with or without HSCT. Significantly more patients in group A were in molecular remission (56% vs 39% P=0.005) and free of drug treatment (56% vs 6% P<0.001). Differences in symptoms and Karnofsky score were not significant. In the era of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, HSCT remains a valid option when both disease and transplant risk are considered.

Introduction

The advent of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has profoundly changed the outlook for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). The majority of patients with this previously fatal disease achieve a long-lasting clinical, hematological, cytogenetic and, in a substantial proportion, molecular remission of their disease. Still, for most patients probably lifelong drug treatment is required.1, 2, 3 Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) from an allogeneic healthy donor achieves a consistent eradication of the malignant clone in the majority of patients. On the downside, HSCT is limited to patients with an available donor and remains associated with significant morbidity and mortality.4, 5 Hence, use of HSCT has changed over the past decade from an early intervention to a treatment that has been deferred in the lines of therapy.6, 7, 8

Current recommendations advise that HSCT should be reserved for patients who are resistant or intolerant to at least one second-generation TKI or for patients with blastic phase. HSCT is primarily considered as a salvage procedure.9, 10 There are no prospective randomized studies to prove this concept. The recommendations are based on the stunning early results of imatinib compared with interferon-α-based therapies.1, 3, 11 They are, in part, supported by an earlier prospective randomized study from our group where HSCT was associated with increased early mortality.12

This view might need to be modified. Transplant-related mortality has declined, standardization and accreditation have improved treatment and risk factors for transplant outcome have been defined.13, 14, 15 In a recent study with predetermined criteria, survival of carefully selected patients with low-risk scores and allogeneic HSCT was similar to a risk-matched group of patients treated with imatinib.16 HSCT offers a reasonable option for patients with advanced disease and low transplant risk, but outlook for patients transplanted with high transplant risk in advanced refractory disease remains limited.15, 17 With a better knowledge on risk factors as compared with CML-study III, this study aimed to look for clinically relevant differences between early allogeneic HSCT and best drug treatment in patients eligible for both strategies. Clinically relevant differences comprise higher probabilities of survival and molecular remission, of living without treatment, with less symptoms and a higher Karnofsky score. Supported by prognostic scores, risk groups with a particular benefit should be identified.

Patients and methods

Study design

This prospective randomized multicenter CML-study IIIA of the German CML-study group followed the previously published concept of CML-study III.12 Patients with newly diagnosed CML were assessed for eligibility to HSCT (for details see Supplementary eMethods). A suitable patient was genetically randomized to primary allogeneic HSCT (group A) if a matched family donor was reported to be available; if no matched family donor was identified, the patient was randomized to best available drug treatment (group B). As a key difference, risk factors associated with allogeneic HSCT were integrated.14 Teams were urged to perform HSCT within 1 year from diagnosis. They were instructed to refrain from interferon-α treatment within 90 days before HSCT to avoid an interferon-associated increase of non-relapse mortality.18 As a second difference, and according to some promising preliminary data, autologous SCT was added into the control arm in an attempt to improve best available drug treatment.19

Patients

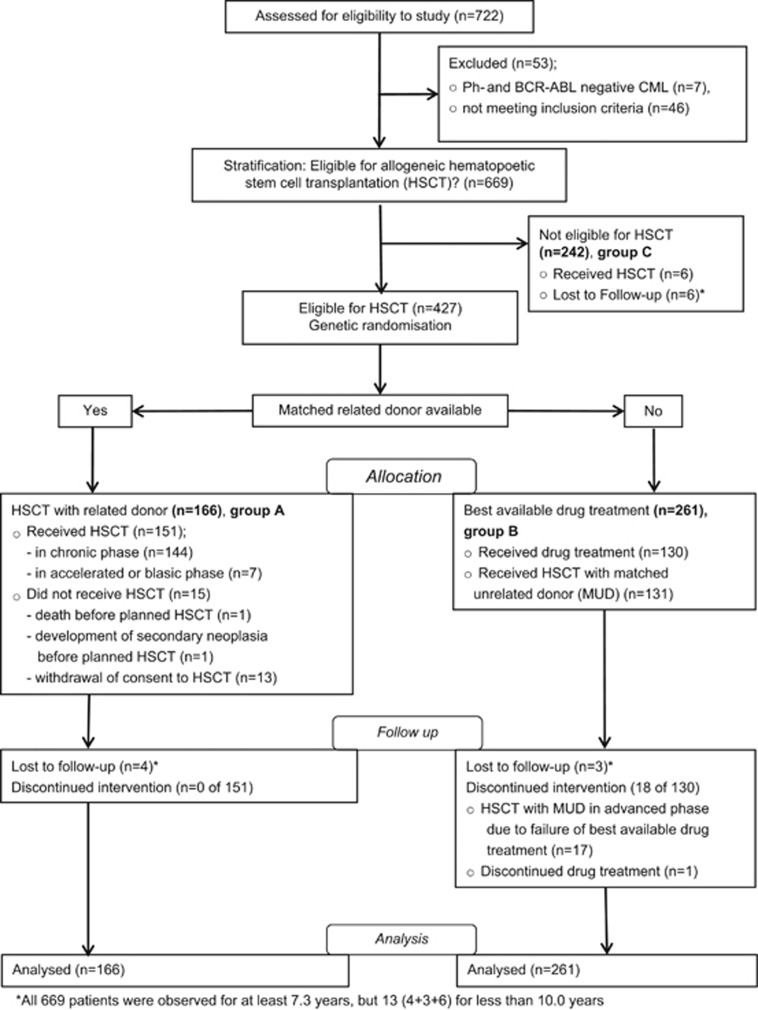

Between July 1997 and January 2004, a total of 722 patients were consecutively registered at the central data management office by 143 participating centers (35 university based, 72 municipal hospital based and 36 office based)20 (see Supplementary eAcknowledgements). Of these, 669 patients with BCR-ABL-positive CML fulfilled the inclusion criteria and entered the study. All patients considered eligible for transplantation (n=427) were randomized within 2 months from registration to group A (n=166) or best available drug treatment (group B; n=261) (Figure 1). Patients not eligible for HSCT were older and had a higher disease score compared with the eligible ones; patients in group A were significantly younger (38 vs 41 years; P=0.03) compared with those in group B; otherwise, no statistically significant differences between groups A and B were observed (Table 1). Patients were analyzed as of May 2014.

Figure 1.

Consort flow diagram of enrollment, allocation, follow-up and analysis of patients. In group B, all 261 patients started with best available drug treatment. During the course of disease, 131 patients received an allogeneic HSCT with an unrelated donor in first CP. Their survival time was censored at the day of transplant. Ph, Philadelphia.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics at diagnosis.

| Variable, number (n) of evaluable patients | Group A: Eligible for HSCT and related donor available | Group B: Eligible for HSCT and no related donor | Group C: Not eligible for HSCT | Total | Group A vs group B, P-value | Groups A and B vs group C, P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients eligible for analysis | 166 (25% of 669) | 261 (39% of 669) | 242 (36% of 669) | 669 | ||

| Median age (years) (range), n=669 | 38 (16–58) | 41 (13–64) | 62 (24–85) | 49 (13–85) | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Age group at diagnosis, n=669 | 0.17 | <0.001 | ||||

| % with age <20 years, n=14 (2% of 669) | 3.6 | 3.1 | 0 | 2.1 | ||

| % with age 20–40 years, n=218 (33% of 669) | 54.8 | 46.0 | 2.9 | 32.6 | ||

| % with age >40 years, n=437(65% of 669) | 41.6 | 51.0 | 97.1 | 65.3 | ||

| Euro score, risk group, n=605 | 0.34 | <0.001 | ||||

| % with low risk, n=263(43% of 605) | 59.5 | 56.1 | 19.4 | 43.5 | ||

| % with intermediate risk, n=260 (43% of 605) | 32.0 | 30.4 | 63.5 | 43.0 | ||

| % with high risk, n=82 (14% of 605) | 8.5 | 13.5 | 17.1 | 13.6 | ||

| % with male sex, n=669 | 59.0 | 65.9 | 61.2 | 62.5 | 0.18 | 0.62 |

| Median spleen size (cm) bcm (range), n=617 | 3 (0–25) | 2 (0–30) | 0 (0–28) | 1 (0–30) | 0.51 | <0.001 |

| Fatigue, n=656 | 48.2 | 48.8 | 47.0 | 48.0 | 0.92 | 0.74 |

| Symptoms due to organomegaly, n=651 | 25.5 | 21.3 | 14.7 | 20.0 | 0.34 | 0.01 |

| % with weight loss of more than 10%, n=651 | 19.6 | 18.0 | 15.5 | 17.5 | 0.70 | 0.33 |

| % with fever, n=651 | 6.8 | 9.7 | 3.4 | 6.8 | 0.37 | 0.01 |

| % with extramedullary manifestation, n=636 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 0.78 | 0.13 |

| Median hemoglobin (g/dl) (range), n=649 | 11.6 (5.7–16.4) | 11.9 (6.2–17.2) | 12.4 (6.4–17.7) | 12.2 (5.7–17.7) | 0.24 | <0.001 |

| Median WBC (countx109/l) (range), n=650 | 143 (13–436) | 112 (3–613) | 83 (8–594) | 102 (3–613) | 0.16 | <0.001 |

| Median PB eosinophils (%) (range), n=641 | 2 (0–17) | 2 (0–14) | 2 (0–12) | 2 (0–17) | 0.87 | 0.35 |

| Median PB basophils (%) (range), n=641 | 3(0–27) | 3 (0–32) | 3 (0–27) | 3 (0–32) | 0.60 | 0.20 |

| Median PB blasts (%) (range), n=643 | 2 (0–18) | 1 (0–25) | 1 (0–15) | 1 (0–25) | 0.23 | 0.04 |

| Median BM blasts (%) (range), n=426 | 3 (0–28) | 3 (0–30) | 3(0–29) | 3 (0–30) | 0.41 | 0.23 |

| Median platelet (countx109/l) (range), n=645 | 373 (46–1696) | 366 (76–2297) | 379 (38–4535) | 372 (38–4535) | 0.57 | 0.86 |

Abbreviations: bcm, Below costal margin; BM, bone marrow; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; PB, peripheral blood, WBC, white blood cell.

Allogeneic HSCT

A total of 305 patients received allogeneic HSCT, 151 patients (144 with a matched, 7 with a mismatched family donor) in group A, 148 patients in group B (all with an unrelated donor; 131 in first chronic phase (CP), 17 in advanced phase) and 6 originally non-eligible patients in group C (Figure 1 and Supplementary eTable 1). The median time from diagnosis to transplantation from a matched related donor was 7 months (range: 2–33 months). The recommended treatment before HSCT was hydroxyurea. The source of stem cells was bone marrow for 64 patients (42%) and peripheral blood for all others. In the 30 centers of four countries, preparative regimens were classified according to the CIBMTR (Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research) functional definitions.21 Standard conditioning was applied in 116 patients (77%). Graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis was primarily cyclosporine based (62%).

Drug treatment

At the time of recruitment to this study in the pretyrosine kinase inhibitor era, the recommended primary drug treatment consisted of interferon in combination with hydroxyurea and low-dose cytosine arabinoside as described before.12 With its availability, imatinib was offered in the case of interferon failure or upon request. Over time, a total of 183 patients received imatinib or a second-generation TKI, 47 in group A (28%) and 136 in group B (84% of 113 patients who did not undergo transplantation and 28% of 148 patients who underwent unrelated donor HSCT). After starting with imatinib (n=181), 16 patients switched to dasatinib and 12 patients to nilotinib.

A total of 44 patients in CP were randomized to autologous HSCT. There was no difference between autologous HSCT and drug treatment, hence they were analyzed as ‘drug treatment'.19

Molecular analysis

BCR-ABL transcript levels were determined every 3 months until year 3, then every 6 months as described previously.22 A major molecular response was defined by a BCR-ABL/ABL ratio of 0.1 or lower, and a complete molecular response, by undetectable BCR-ABL transcripts using total ABL as an internal sensitivity control.

Ethics

The protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty Mannheim of the University of Heidelberg and by the local ethics committees of participating centers. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before entering the study. The study protocol is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00025402).

Statistical analysis

Outcome of the groups A and B was analyzed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Primary end point was survival time from diagnosis. Secondary end points included ongoing CML therapy, absence of detectable BCR-ABL transcripts, presence of symptoms and Karnofsky performance score, all at 10 years after diagnosis. Survival times of patients in group B who received an unrelated donor HSCT in first CP were censored at the day of transplantation as these transplantations were performed independent of prior treatment success and early transplant-related mortality cannot be linked to survival probabilities with best available drug treatment. Patients undergoing transplantation in accelerated phase or blast crisis were not censored, as drug treatment had failed before. Survival probabilities were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Assuming a late crossing of survival curves for the main comparison between groups A and B,23 overall survival and survival after the crossing were compared with the Wilcoxon–Gehan test. The influence of HSCT as salvage treatment in blast crisis was analyzed by Simon–Makuch curves24 and Mantel–Byar test.25 Patients were stratified for disease risk by the Euro score26 calculated at diagnosis and for transplant risk by the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) score, calculated at the time of allogeneic HSCT.14 To be able to compare survival probabilities from diagnosis and to avoid time-to-transplantation bias, adapted EBMT scores were computed for all 427 patients eligible for HSCT. The algorithm for calculation and the determination of median P-values is given in the Supplementary eMethods.

The significance level α was chosen to be 0.05 two-sided. All survival comparisons within subgroups are understood as explorative analyses; adjustments for multiple comparisons were not performed. Patients' characteristics at baseline were descriptively compared using Fisher's test or Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney U-test, as appropriate.

Code availability

All analyses were performed with the program package SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Survival

Median survival of all 669 patients was not reached. Ten-year survival probability was 0.61 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.57–0.65). Median observation time for living patients was 12.1 years (range, 7.3–16.1 years). Survival probabilities were better for the 427 patients eligible for HSCT than for the 242 non-eligible patients (Supplementary eFigure 1a).

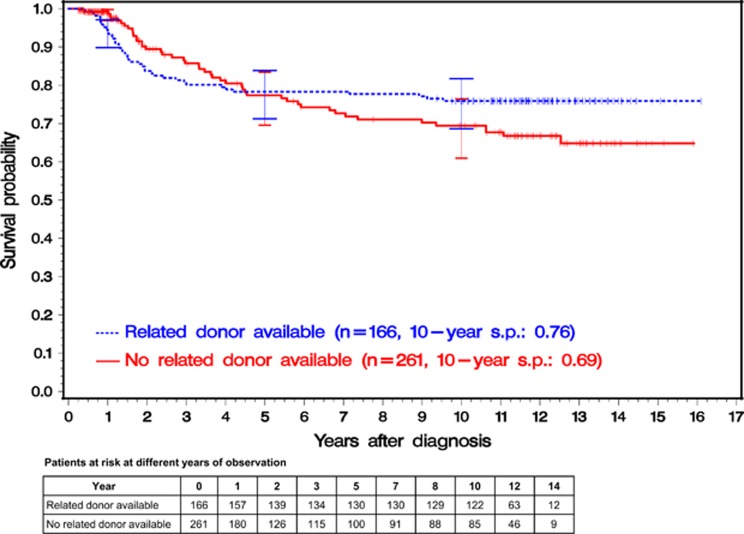

Overall and before the crossing of the survival curves at 4.5 years, survival was not significantly different between groups A and B. Before the crossing, 36 patients (22% of 166) in group A (primary HSCT) died, whereas in group B (best available drug treatment), 31 (12% of 261) died and 128 (49%) were censored because of allogeneic HSCT with an unrelated donor in first CP (Figure 2). From 4.5 years on, survival probabilities in group A were significantly higher (Wilcoxon–Gehan test: P<0.001). Ten-year survival probabilities were 0.76 (95% CI: 0.69–0.82) in group A and 0.69 (95% CI: 0.61–0.76) in group B.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival of the 427 patients stratified according to genetic randomization. Of 427 patients, 166 were randomized to early allogeneic HSCT (group A) and 261 patients to best available drug treatment (group B). Analysis was performed by intention to treat. In group B, the survival time of patients receiving an allogeneic HSCT with an unrelated donor was censored at the day of transplant. The overall survival differences between the two curves were not significant (Wilcoxon–Gehan test). At 1, 5 and 10 years, horizontal crossbars indicate the upper and lower limits of the 95% CIs for the estimated survival probabilities (s.p.).

Euro score, EBMT risk score, adapted EBMT risk score and outcome

The Euro score was an appropriate prognostic system for the 261 patients with drug treatment. Patients with low, intermediate or non-evaluable risk had a significantly better survival compared with the high-risk group (P=0.002; Supplementary eFigure 1b) with no significant difference between the former groups. The EBMT risk score was able to discriminate survival within the 151 patients actually transplanted in group A (overall P=0.002; Supplementary eFigure 1c) as well as between all 305 patients transplanted within the whole patient population (Supplementary eFigure 1d).

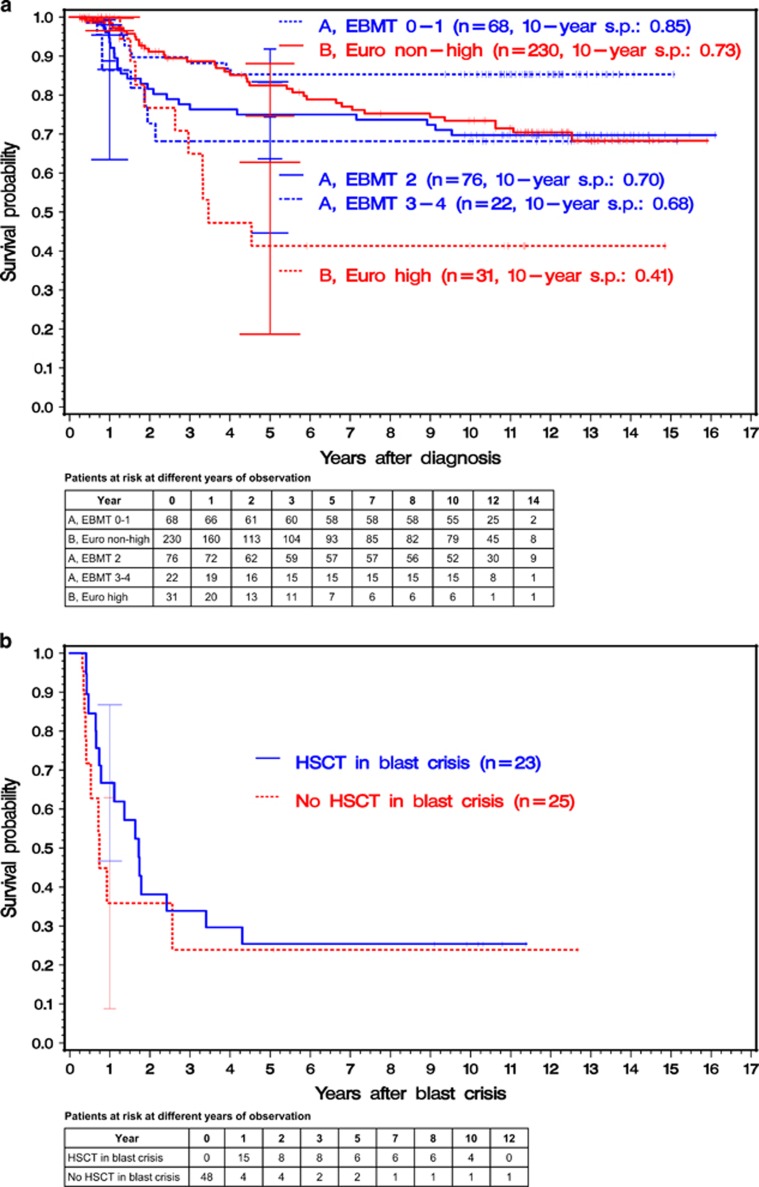

As expected, the adapted EBMT risk score at diagnosis had a prognostic impact on outcome in group A (Supplementary eFigure 2a) but not in group B (Supplementary eFigure 2b). Hence, five prognostic groups at diagnosis could be differentiated: three risk groups defined by the adapted EBMT score from diagnosis for group A and two risk groups defined by the Euro score in group B (Figure 3a). Patients of group A with adapted EBMT scores 0–1 (10-year survival probability 0.85 (95% CI: 0.74–0.92) had significantly higher survival probabilities (median P<0.001) as compared with patients with high-risk Euro score of group B (10-year survival probability: 0.41 (95% CI: 0.19–0.63)) and also as compared with the 230 non-high-risk patients (median P=0.047; 10-year survival probability: 0.73 (95% CI: 0.65–0.80)). In contrast, there were no statistically significant survival differences of patients in group A with adapted EBMT score 2 (10-year survival probability: 0.70 (95% CI: 0.58–0.79)) or scores 3–4 (10-year survival probability: 0.68 (95% CI: 0.45–0.83)) when compared either with the non-high-risk or the high-risk patients of group B.

Figure 3.

(a) Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival since diagnosis of the 427 patients eligible for allogeneic HSCT with a related donor. At diagnosis, all 166 patients randomized to group A were stratified according to the adapted EBMT risk score at diagnosis and all 261 patients randomized to group B were stratified according to disease risk (Euro score) at diagnosis. Analysis was performed by intention to treat. In group B, the survival time of patients receiving an allogeneic HSCT with an unrelated donor was censored at the day of transplant. With EBMT score 0 or 1 in group A, survival probabilities were significantly higher compared with the survival probabilities of Euro high- (log-rank test: median P<0.001) and Euro non-high-risk patients (log-rank test: median P=0.047) in group B. At 1 and 5 years, horizontal crossbars indicate the upper and lower limits of the 95% CIs for the estimated survival probabilities. The abbreviation ‘s.p.' stands for 'survival probability'. (b) Simon–Makuch estimates of overall survival of 48 patients with blast crisis. Patients were stratified according to the reception of allogeneic HSCT as salvage therapy. All patients started in the non-transplant group. If transplanted, patients changed to the HSCT group at the time of transplant (finally, 23 were transplanted). Survival differences were not significant (Mantel–Byar test). At 1 year, horizontal crossbars indicate the upper and lower limits of the 95% CIs for the estimated survival probabilities.

Blast crisis occurred in 48 (11%) of the 427 eligible patients. Of these, 23 received HSCT for treatment of blast crisis. Median time to transplantation after beginning of blast crisis was 3.6 months. Thirteen of the 23 patients started with imatinib therapy before HSCT. Regarding the 25 patients without HSCT in blast crisis, 15 had started imatinib treatment before blast crisis, 6 started imatinib treatment after blast crisis and 4 have neither received imatinib nor HSCT. Survival probabilities were not significantly different between patients treated or not with HSCT (Mantel–Byar test; Figure 3b).

Causes of death

The causes of death differed between groups A and B (P<0.001; Supplementary eTable 2). Transplant-related mortality was the most frequent cause of death with 63% of all causes in group A. Disease progression was the most frequent cause of death in group B (60% not considering causes of death if transplanted with an unrelated donor in first CP). Ten percent (group A) and 23% (group B) of causes of death were reported as not directly related to the disease or the transplant.

Patient status at 10 years

Concerning all comparative analyses on patient status at 10 years, the 131 recipients of unrelated donor HSCT in first CP were not considered. Reporting on the 296 remaining patients according to the intention-to-treat principle, 291 patients (98%) had sufficient follow-up. At 10 years, 122 (75%) of the 162 patients with a related donor and 86 (67%) of the 129 patients without related donor were still alive (Table 2).

Table 2. Status at 10.0 years after diagnosis for 296 patients eligible for allogeneic HSCT.

| Group A | Group B | Total A vs B P-value | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

With HSCT |

Without HSCT | Total A | With HSCT Not in CP | Without HSCT | Total B | ||||

| In CP | Not in CP | ||||||||

| Number at entry | 141 | 6 | 15 | 162 | 17 | 112 | 129 | — | 291a |

| n alive at 10 years | 109/141 | 2/6 | 11/15 | 122/162 | 4/17 | 82/112 | 86/129 | — | 208/291 |

| % | 77 | 33 | 73 | 75 | 24 | 73 | 67 | 71 | |

| n without CML drug treatment | 86/136 | 1/6 | 1/15 | 88/157 | 4/17 | 3/110 | 7/127 | <0.001 | 95/284b |

| % | 63 | 17 | 7 | 56 | 24 | 3 | 6 | 33 | |

| n with molecularly undetectable BCR/ABL | 71/120 | 2/6 | 6/14 | 79/140 | 3/17 | 46/109 | 49/126 | 0.005 | 128/266c |

| % | 59 | 33 | 43 | 56 | 18 | 42 | 39 | 48 | |

| n with Karnofsky score > 80 | 85/122 | 1/5 | 8/14 | 94/141 | 3/17 | 60/96 | 63/113 | 0.09 | 157/254d |

| % | 70 | 20 | 57 | 67 | 18 | 63 | 56 | 62 | |

| n without symptoms | 70/121 | 1/5 | 5/14 | 76/140 | 1/17 | 56/98 | 57/115 | 0.53 | 133/255e |

| % | 58 | 20 | 36 | 54 | 6 | 57 | 50 | 52 | |

Abbreviations: CP, chronic phase; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Of 296 patients eligible for allogeneic HSCT, 291 patients were either observed for at least 10.0 years or died before.

Data were missing for 7 patients who were alive at 10 years.

Data were missing for 25 patients who were alive at 10 years.

Data were missing for 37patients who were alive at 10 years.

Data were available for 36 patients who were alive at 10 years.

At the time of analysis, significantly more patients in group A (56% of 157, (95% CI: 48–64%)) were alive and without CML treatment than in group B (6% of 127, (95% CI: 2–11%); P<0.001) and significantly more patients in group A (56% of 140, (95% CI: 48–65%)) than in group B (39% of 126, (95% CI: 30–48%); P=0.005) were in molecular remission. Details on the kind of treatment given at 10 years are provided by Supplementary eTable 3.

There were no significant differences between groups A and B regarding the number of patients with a Karnofsky score below 80% or reporting symptoms.

Patients transplanted in first CP with an unrelated donor

In group B, 131 patients were transplanted in first CP with an unrelated donor. Owing to unknown reasons why patients were selected, the immanent selection of 131 less frail patients surviving up to the day of transplantation, and ‘guaranteed' survival between diagnosis and the day of transplantation, an unbiased comparative analysis between these patients and either the patients of group A or the 130 patients of group B not transplanted in first CP was not possible. Interpreting their outcome with this in mind, 10 years after transplantation, 118 of the 131 patients had either died (n=54) or were still alive (n=64, 54%). Fifty percent patients of the 118 patients were without therapy, 45% with undetectable BCR/ABL, 45% with a Karnofsky score >80 and 36% without symptoms. Thirteen patients were alive but not observed for 10 years.

Discussion

Long-term overall survival in this multicenter prospective randomized CML-study IIIA was not different whether patients were randomized to primary HSCT or to best available drug treatment. There was no difference in performance status and symptom reporting between the groups at time of the analysis. However, significantly more patients assigned to early transplant were in complete molecular remission at 10 years and free of CML treatment. Outcome was determined by three key factors: disease risk, transplant risk and treatment allocation. Integrating these predetermined factors at diagnosis into the intention-to-treat analysis, patients with HSCT and a low EBMT risk score (0–1) showed no excess mortality and fared significantly better than patients with no donor. In contrast, the concept of salvage HSCT in advanced disease despite a high EBMT score failed.

The present data contradict some previous findings and current concepts.1, 2, 9, 10 They can be criticized for their relevance in the times of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, of high-resolution molecular HLA typing and of availability of more than 20 million typed unrelated volunteer donors worldwide when outcome after a well-matched unrelated donor HSCT might be even better than after a sibling donor transplant.1, 27, 28, 29 And, the present results are derived from a study designed 20 years ago in the preimatinib era. Nevertheless, we consider the main findings as valid. Outcome after HSCT can be predicted as has been repeatedly validated. Risks are approximately additive; outcome is substantially better for young patients with early disease, a short time interval from diagnosis and a well-matched, gender identical donor than for older patients with more advanced disease, a longer time interval from diagnosis, a mismatched female donor for a male recipient, independent of stem cell source or transplant technique.14

There are some notes of caution. The results differ substantially from those of the previous CML-study III.12 This could be explained by differences in the risk profile of the patients transplanted with a related donor in first CP in group A (144 of 166 patients in CML-study IIIA).23 Significantly improved survival results for these patients led to a different outcome in the comparison between groups A and B and thus to different conclusions. In the CML-study IIIA, transplants had to be performed whenever possible within 1 year from diagnosis. In addition, outcome of HSCT has significantly improved over the past decade. The majority of the patients (51%) received imatinib or a second-generation TKI before transplantation or in the later course of their disease. In a complex multicenter study involving many participants, patients and donors, local physicians, CML-study centers and transplant teams, different opinions prevail. The impact of standardized strategies in qualified centers has only recently been recognized.15, 20 Timing was not always consistent, transplant protocols or drug treatment schedules could have been modified. A statistical model can neither adjust for all variables nor consider a subjective decision for HSCT with an unrelated donor transplant in first CP. However, randomization of patients with a related donor, analysis in accordance with intention to treat and the use of an adapted EBMT score at time of diagnosis considerably reduced the selection and the time-to-transplant bias. Reducing this bias, results showed no early excess mortality for the HSCT group.

Outcome of HSCT with high transplant risk score has not improved over the past decade.15 In our series, the comparative analysis of the salvage treatment after start of blast crisis was limited by the small patient number (n=48) and the unknown reasons why some patients were selected for HSCT. Independent of that, no patient with EBMT risk score 6 or 7 survived long term.

Although the best available drug treatment has meanwhile considerably improved and a significant survival difference with Euro non-high-risk patients are less likely, the favorable survival results of the patients with low EBMT score are noteworthy on their own; in particular, as the results are based on an intention-to-treat analysis and on a median observation time beyond 10 years. Without the expense of early excess mortality, patients with newly diagnosed high-risk CML and non-responders to first-line TKI can benefit from an early low-risk HSCT through improved long-term survival, shorter time of treatment, a higher rate of molecular remissions and lower health-care costs. Our data fit with a recent comparison in the imatinib era. Patients with an early low-risk HSCT showed no early excess mortality but a significantly higher rate of molecular remissions as compared with those on imatinib treatment.16 Taken together, these recent data and the results from this long-term study indicate that patients with a low transplant score who failed initial tyrosine kinase inhibitors might be considered for an early HSCT rather than rescue drug treatment. Assessment of donor availability will be a prerequisite to achieve this goal; renouncement for HSCT in the absence of a low-risk donor as well. HSCT for advanced disease with a high transplant risk should not be advocated; ongoing drug treatment or best supportive care might be the better option and will also save costs.30, 31 The overall strategy should involve close cooperation between local physicians, treatment centers and transplant teams. The concept of donor versus no donor should probably change to a risk-adapted strategy, defined by disease and transplant risk for acquired hematological disorders in general.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), Grant 01G 19980/6 (Kompetenznetz Akute und Chronische Leukämien) and by grants from Hoffmann-La Roche, Essex Pharma and Amgen. Arthur Gil (BSc, IBE, LMU München) supported the preparation of the data for the analysis and provided the tables and their results. A list of all participating centers and all transplantation centers is attached to the online-only supplement (Supplementary eAcknowledgements). Including also the patients who received autologous transplantation, 33 centers transplanted 348 patients. Quality control of documentation forms and technical support was provided by Inge Stalljann, Matthias Dumke, Gabriele Bartsch, Gabriele Lalla, Christiane Folz, Regina Pleil-Lösch, Elke Matzat, Hannelore Ihrig, Andrea Elett, Maike Haas and Rosi Leichtle. Quality control of documentation forms and technical support was provided by Inge Stalljann, Matthias Dumke, Gabriele Bartsch, Gabriele Lalla, Christiane Folz, Regina Pleil-Lösch, Elke Matzat, Hannelore Ihrig, Andrea Elett, Maike Haas and Rosi Leichtle.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Leukemia website (http://www.nature.com/leu)

Dr Pfirrmann reports personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, outside the submitted work; Dr Scheid reports personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, personal fees from Pfizer, outside the submitted work; Dr Mayer reports other from German CML Study Group, during the conduct of the study; grants and non-financial support from BMS, grants and non-financial support from Novartis, outside the submitted work; Dr Haferlach and Dr Schnittger report other from MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory, outside the submitted work; and Dr Susanne Schnittger is employed by and partly owns the MLL Munich Leukemia Laboratory; Dr Reiter reports personal fees and other from Novartis, outside the submitted work; Dr Saußele reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Novartis, personal fees and non-financial support from Pfizer, personal fees from ARIAD, outside the submitted work; Dr Hochhaus reports grants from Novartis, BMS, ARIAD, Pfizer, outside the submitted work; Dr Hehlmann reports grants from Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Kompetenznetz Akute und Chronische Leukämien, Grant No. 01G 19980/6), grants from Hoffmann-La Roche, grants from Essex Pharma, grants from AMGEN, during the conduct of the study; grants from Novartis, grants and personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, outside the submitted work. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Apperley JF. Chronic myeloid leukaemia. Lancet 2015; 385: 1447–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehlmann R. A chance of cure for every patient with chronic myeloid leukemia? N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 980–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien S, Guilhot F, Larson RA, Gathmann I, Baccarani M, Cervantes F et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 994–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speck B, Bortin MM, Champlin R, Goldman JM, Herzig RH, McGlave PB et al. Allogeneic bone-marrow transplantation for chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Lancet 1984; 1: 665–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 1813–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fefer A, Einstein AB, Thomas ED, Buckner CD, Clift RA, Glucksberg H et al. Bone-marrow transplantation for hematologic neoplasia in 16 patients with identical twins. N Engl J Med 1974; 290: 1389–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passweg JR, Baldomero H, Bader P, Bonini C, Cesaro S, Dreger P et al. Hematopoietic SCT in Europe 2013: recent trends in the use of alternative donors showing more haploidentical donors but fewer cord blood transplants. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015; 50: 476–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratwohl A, Baldomero H, Gratwohl M, Aljurf M, Bouzas LF, Horowitz M et al. Quantitative and qualitative differences in use and trends of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a Global Observational Study. Haematologica 2013; 98: 1282–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Rosti G, Hochhaus A, Soverini S, Apperley JF et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood 2013; 122: 872–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. Treatment options for chronic-phase CML. High-dose therapy followed by allogeneic BMT or SCT. Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/CML/HealthProfessional/Page4#Section_271 (last assessed 21 February 2015).

- Hughes TP, Hochhaus A, Branford S, Müller MC, Kaeda JS, Foroni L et al. Long-term prognostic significance of early molecular response to imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia: an analysis from the International Randomized Study of Interferon and STI571 (IRIS). Blood 2010; 116: 3758–3765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehlmann R, Berger U, Pfirrmann M, Heimpel H, Hochhaus A, Hasford J et al. Drug treatment is superior to allografting as first-line therapy in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 2007; 109: 4686–4692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooley TA, Chien JW, Pergam SA, Hingorani S, Sorror ML, Boeckh M et al. Reduced mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 2091–2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratwohl A, Hermans J, Goldman JM, Arcese W, Carreras E, Devergie A et al. Risk assessment for patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia before allogeneic blood or marrow transplantation. Chronic Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Lancet 1998; 352: 1087–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratwohl A, Brand R, Niederwieser D, Baldomero H, Chabannon C, Cornelissen J et al. Introduction of a quality management system and outcome after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 1980–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saussele S, Lauseker M, Gratwohl A, Beelen DW, Bunjes D, Schwerdtfeger R et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo SCT) for chronic myeloid leukemia in the imatinib era: evaluation of its impact within a subgroup of the randomized German CML Study IV. Blood 2010; 115: 1880–1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyekunle A, Zander AR, Binder M, Ayuk F, Zabelina T, Christopeit M et al. Outcome of allogeneic SCT in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in the era of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Ann Hematol 2013; 92: 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehlmann R, Hochhaus A, Kolb HJ, Hasford J, Gratwohl A, Heimpel H et al. Interferon-alpha before allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in chronic myelogenous leukemia does not affect outcome adversely, provided it is discontinued at least 90 days before the procedure. Blood 1999; 94: 3668–3677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CML Autograft Trials Collaboration. Autologous stem cell transplantation in chronic myeloid leukaemia: a meta-analysis of six randomized trials. Cancer Treat Rev 2007; 33: 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauseker M, Hasford J, Pfirrmann M, Hehlmann R, , German CMLSG. The impact of health care settings on survival time of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 2014; 123: 2494–2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warlick E, Ahn KW, Pedersen TL, Artz A, de Lima M, Pulsipher M et al. Reduced intensity conditioning is superior to nonmyeloablative conditioning for older chronic myelogenous leukemia patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplant during the tyrosine kinase inhibitor era. Blood 2012; 119: 4083–4090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soverini S, Hochhaus A, Nicolini FE, Gruber F, Lange T, Saglio G et al. BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation analysis in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of European LeukemiaNet. Blood 2011; 118: 1208–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfirrmann M, Saussele S, Hochhaus A, Reiter A, Berger U, Hossfeld DK et al. Explaining survival differences between two consecutive studies with allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2014; 140: 1367–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon R, Makuch RW. A non-parametric graphical representation of the relationship between survival and the occurence of an event: application to responder versus non-responder bias. StatMed 1984; 3: 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N, Byar DP. Evaluation of response-time data involving transient states: an illustration using heart-transplant data. J Am Stat Assoc 1974; 69: 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hasford J, Pfirrmann M, Hehlmann R, Allan NC, Baccarani M, Kluin-Nelemans JC et al. A new prognostic score for survival of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with interferon alfa. Writing Committee for the Collaborative CML Prognostic Factors Project Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998; 90: 850–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innes AJ, Apperley JF. Chronic myeloid leukemia-transplantation in the tyrosine kinase era. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am 2014; 28: 1037–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehlmann R, Muller MC, Lauseker M, Hanfstein B, Fabarius A, Schreiber A et al. Deep molecular response is reached by the majority of patients treated with imatinib, predicts survival, and is achieved more quickly by optimized high-dose imatinib: results from the randomized CML-study IV. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gragert L, Eapen M, Williams E, Freeman J, Spellman S, Baitty R et al. HLA match likelihoods for hematopoietic stem-cell grafts in the U.S. registry. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 339–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavey T, Hoyle M, Ciani O, Crathorne L, Jones-Hughes T, Cooper C et al. Dasatinib, nilotinib and standard-dose imatinib for the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia: systematic reviews and economic analyses. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England) 2012; 16, iii-iv, 1–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo XD, Jiang Q, Xu LP, Liu DH, Liu KY, Jiang B et al. Health-related quality of life of patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia treated with allogeneic hematopoietic SCT versus imatinib. Bone Marrow Transplant 2014; 49: 576–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.