Abstract

Vascular inflammation is a common cause of renal impairment and a major cause of morbidity and mortality of patients with kidney disease. Current studies consistently show an increase of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in acute vasculitis and in patients with atherosclerosis. Recent research has elucidated mechanisms that mediate vascular wall leukocyte accumulation and differentiation. This review addresses the role of EVs in this process. Part one of this review addresses functional roles of EVs in renal vasculitis. Most published data address anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis and indicate that the number of EVs, mostly of platelet origin, is increased in active disease. EVs generated from neutrophils by activation by ANCA can contribute to vessel damage. While EVs are also elevated in other types of autoimmune vasculitis with renal involvement such as systemic lupus erythematodes, functional consequences beyond intravascular thrombosis remain to be established. In typical hemolytic uremic syndrome secondary to infection with shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli, EV numbers are elevated and contribute to toxin distribution into the vascular wall. Part two addresses mechanisms how EVs modulate vascular inflammation in atherosclerosis, a process that is aggravated in uremia. Elevated numbers of circulating endothelial EVs were associated with atherosclerotic complications in a number of studies in patients with and without kidney disease. Uremic endothelial EVs are defective in induction of vascular relaxation. Neutrophil adhesion and transmigration and intravascular thrombus formation are critically modulated by EVs, a process that is amenable to therapeutic interventions. EVs can enhance monocyte adhesion to the endothelium and modulate macrophage differentiation and cytokine production with major influence on the local inflammatory milieu in the plaque. They significantly influence lipid phagocytosis and antigen presentation by mononuclear phagocytes. Finally, platelet, erythrocyte and monocyte EVs cooperate in shaping adaptive T cell immunity. Future research is needed to define changes in uremic EVs and their differential effects on inflammatory leukocytes in the vessel wall.

Keywords: Extracellular vesicle, Atherosclerosis, Kidney disease, Glomerulonephritis, Macrophage

Core tip: This review addresses the role of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in vascular inflammation that can cause renal damage and is also shaped by uremic mediators. Vasculitides are common causes of renal damage. Functionally, neutrophil EVs induced by anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody contribute to endothelial damage. EVs are main distributors of shiga toxin in the circulation and into tissues in typical hemolytic uremic syndrome. In atherosclerosis in patients with and without kidney disease, endothelial EVs are elevated. Uremic EVs are deficient in mediating vascular relaxation. EVs modulate mononuclear phagocyte differentiation, cytokine production, lipid phagocytosis and antigen presentation, atherosclerotic inflammatory processes significantly altered in uremia.

INTRODUCTION

Subcellular membrane vesicles collectively termed extracellular vesicles (EVs) are a third pathway of intercellular communication between direct cell-to-cell contact and secretion of soluble signaling molecules[1]. EVs can be secreted by virtually all cell types and contain a variety of components[2,3]. They are already present under physiologic conditions in a variety of bodily fluids[4]. EVs critically modulate local and systemic inflammatory and immune processes[4-7]. How EVs affect leukocytes and their function in the arterial wall in patients with kidney disease will be discussed for both acute vasculitis and chronic vascular inflammation in atherosclerosis.

LEUKOCYTES IN THE VASCULAR WALL

Leukocytes are an integral part of the healthy vessel[8,9] and differentially increase in vascular inflammation[10]. The arterial wall is invaded by blood leukocytes in inflammation both directly across the main vascular endothelium and through vasa vasorum of larger vessels. This process is a tightly regulated cascade of leukocyte activation, rolling, adhesion and transmigration, to date studied mostly in neutrophilic granulocytes[11-13]. Vascular inflammation is mostly found in the arterial tree and microvessels including glomerular capillaries. Inflammation of the much thinner venous wall is rarely a clinical problem beyond reaction to intravascular thrombosis[10]. This is remarkable as most endothelial leukocyte adhesion and transendothelial migration is observed in venules[14]. Vascular inflammation is central in allo-immune processes such as transplant rejection. These have recently been reviewed (among others[15,16]). This review focuses on native arteries and glomerular capillaries.

Impaired renal function during both acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease significantly influences the structure of the arterial wall, affecting arterial endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells[17,18]. Structural changes are most obvious in enhanced atherosclerosis development[19-21]. A prominent feature in humans and mouse models with end stage kidney disease is extraosseous calcification of the arterial media[19,22]. Chronic inflammation in atherosclerosis occurs in normal and reduced kidney function, however, both innate and adaptive leukocytes are specifically altered by renal impairment[23-25].

CHARACTERIZATION OF EVS

Since the first description of “platelet-dust” in 1967[26], EVs were found in diverse biological fluids[27]. Important factors of EV characterization are size and surface markers indicating their cellular origin[5,28-30]. EVs are a very heterogeneous population as both characteristics additionally vary with mode of EV generation[31]. In addition, most of the currently used flow cytometry instruments are not optimal for detection of particles of submicrometer size[32,33]. Organizations such as the Society for Extracellular Vesicles, formed in 2011, and databases such as EVpedia (http://evpedia.org) are instrumental in establishing reliable standards, including specification of preanalytical procedures and basic clinical information[4,27,34].

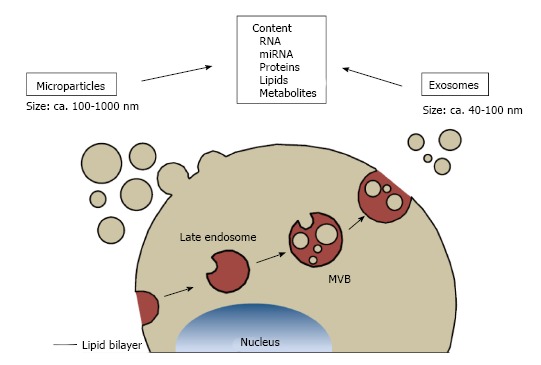

Currently, two main groups of EVs are distinguished by both size and mode of generation: Exosomes and microparticles[1,3,28,29] (Figure 1). Exosomes are small EVs, ranging from 30-100 nm. They originate from endosome-derived multivesicular bodies and are released to the extracellular space when the multivesicular bodies fuse with the plasma membrane[35,36]. Microparticles (also referred to as ectosomes, membrane vesicles, nanovesicles and shedding vesicles) measure 100-1000 nm[3,30,35,37]. They directly bud off from the plasma membrane[35,36]. Both types of vesicles are enclosed by a lipid bilayer, but due to the fact that microparticles directly bud from the plasma membrane, they have a more similar membrane composition to their parent cell than exosomes[28,35]. For example, leukocyte surface proteins such as CD14, CD36 and CD11c are found on leukocyte microparticles[38]. Phosphatidylserine was initially thought to be enriched on microparticles only, but was later also found on exosomes[3]. Exosomes display endosome-associated proteins like annexins, flotillins or CD63 on their surface[28]. However, the expression of these proteins on microparticles cannot be completely excluded[3]. In addition to a possible biological overlap, this also reflects the technical challenge of multicolor fluorescence analysis of small particles[32,33]. Principal intravesicular contents such as cytoplasmic proteins, metabolites, RNAs, microRNAs and lipids can be found in both, exosomes and microparticles, however, in different abundance[2,3,35]. In addition to exosomes and microparticles, apoptotic bodies have been described as a separate entity by some authors[35,36,39]. These have been defined as large (1-5 μm) vesicles generated during apoptosis. However, other EVs also express the inner membrane marker Annexin V on their surface.

Figure 1.

Classification of extracellular vesicles. Types of extracellular vesicles are distinguished by their mode of generation. Microparticles directly bud off the plasma membrane and measure approximately 100-1000 nm. Exosomes are released by fusion of multivesicular bodies with the plasma membrane and their sizes range between 40-100 nm. Both types of extracellular vesicles can contain RNA, microRNA, proteins, lipids and metabolites. MVBs: Multivesicular bodies.

Following current recommendations[29], the overarching term EV will be used for all secreted vesicles in this review and further characterization will be provided by naming specific surface markers.

EVS IN CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE

In end stage renal disease, both the uremic milieu and hemodynamic changes during the dialysis procedure can contribute to EV generation[40]. Uremic toxins such as p-cresol and enoxylsulfate induced EV shedding from HUVECs[41]. Hemoconcentration by dialysis increased blood viscosity, thereby decreasing shear stress and EV generation[42]. In addition, morphologically similar EVs may serve different functions is generated in an uremic milieu - for example, EVs from healthy controls, but not patients with end stage renal disease conferred endothelium mediated arterial relaxation in vitro[43].

Counts and provenience of circulating EVs have been characterized in patients with chronic renal impairment with and without renal replacement therapy. Some studies found elevated serum concentrations of total and CD42+ platelet EV[44-46], total, endothelial (CD31+, CD114+)[43,46], platelet (CD41+), and erythrocyte (CD235+) EVs[43] in patients with end stage renal disease, while in others, total plasma EV concentrations were unaltered[47,48] or only endothelial EVs were increased[41]. Also, the effect of the hemodialysis procedure is controversial with an increase in some[47] but not other studies[44,45]. The currently available studies included relatively small patient numbers and discrepancies that are at least partly explained by pre-analytical variables such as different modes of blood draw, storage and anticoagulation, flow cytometry equipment and surface markers used. However, addressing a possible pathophysiologic cause, a recent study further stratified patients with moderate kidney disease (mean GFR 39 mL/min) according to the presence of cardiovascular disease defined by significant stenosis on coronary angiography[49]. EVs of both platelet (CD42+) and endothelial (CD31+) origin were significantly higher in patients with coronary artery disease, irrespective of renal impairment. Indeed, a large number of observational studies report increased concentrations of circulating EVs in atherosclerosis[50-53]. Especially endothelial EV concentrations appear to be predictive for cardiovascular prognosis[54]. This was confirmed in a recent observation in a large group of 844 individuals from the Framingham offspring cohort. Endothelial EV counts (CD31+ or CD114+) correlated with hypertension, elevated triglycerides the metabolic syndrome and an overall higher Framingham in patients inversely correlated with brachial artery flow-induced dilatation and positively correlated with indices of arterial stiffening[43]. Endothelial (CD31+) EV concentration was associated with severe hypertension in a number of cohorts[55,56]. Concentrations significantly correlated with renal damage manifesting as micro- or macro-albuminuria in this condition[57].

The currently available data is also limited by a mostly cross-sectional study design that precludes detection of temporal changes in single patients[52]. Measurement of EV concentration is evaluated as a predictive factor in a number of ongoing prospective trials[58]. However, there are some longitudinal data for patients with end stage kidney disease. A follow up study of 81 hemodialysis patients for a mean of 50 mo revealed that endothelial (CD31+) EV concentration in serum obtained after the long interval was a significant predictor of all cause and cardiovascular mortality, an association that was not observed for CD41+ platelet, CD11b+ leukocyte or CD235+ erythrocyte EVs[59]. Another prospective study investigated endothelial EV counts (CD31+) in a cohort of 227 patients with end stage renal disease who were scheduled for kidney transplantation[48]. Endothelial EVs significantly decreased during 60 d of longitudinal follow up after kidney transplantation. However, they did not differ from healthy controls at start of the trial[48] which may reflect that these patients represent a subgroup with relatively few co-morbidities.

In summary, chronic elevation of endothelial EVs currently appears to be significantly associated with vascular dysfunction and atherosclerosis in renal disease.

THE ROLE OF EV IN RENAL VASCULITIS

Systemic inflammation is frequently associated with elevated EV concentrations. Pathophysiologically, monocytic and endothelial EVs can directly induce MCP1, interleukin (IL)-6 and VEGF production in human podocytes[60] thus enhancing glomerular injury. Investigations of EVs in systemic lupus erythematodes (SLE), ANCA vasculitis and typical hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) will be reviewed. It is also of note that our literature review revealed no information on EVs in either the pathogenesis or regarding the circulating EV counts in other common forms of renal vasculitis, including postinfectious glomerulonephritis, a historically common cause of renal vascular inflammation, and IgA nephropathy as the currently most common entity in the Western world.

RHEUMATIC DISEASE WITH RENAL INVOLVEMENT

EVs function has been studied in systemic rheumatic disease[61,62]. In SLE, a common rheumatic cause of glomerulonephritis, elevated levels of EVs, particularly of platelet origin, have consistently been detected in patients with active antiphospholipid syndrome[63-66], and also in Sjögrens syndrome[64] and closely been associated to intravascular thrombosis. Mechanisms of modification of inflammation of the vascular wall by EVs in SLE have not been reported to date. However, EVs in SLE display increased amounts of immunoglobulin and complement[67] and it is conceivable that they may contribute to deposition of these in the renal glomerulum. Furthermore, the proteome of these EVs in SLE appears to differ from healthy controls[68] and EVs constituents in SLE such as Galectin 3 binding protein have also been detected in glomerular deposits in individual patients with lupus-associated glomerulonephritis[69].

ANCA ASSOCIATED VASCULITIS

In anti-neutrophil-cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis, a number of studies have shown elevated serum EV concentrations during active disease[47,70-72]. Counts reverted normal during remission. In addition, counts were significantly higher than in patients with other glomerulonephritides such as IgA nephropathy, minimal change disease, diabetic nephropathy but also lupus nephropathy[47,71]. Most EVs in ANCA disease were of platelet origin, but leukocyte and endothelial derived EVs were also found[47,70-73]. Histologically, ANCA vasculitis presents as acute necrotizing vasculitis not only of the glomeruli, but arteries of all sizes with predilection of small vessels[74]. The most prominent infiltrating cell types are neutrophilic granulocytes and even more abundantly, monocytes[75]. However, most research on leukocyte function within the vascular wall has concentrated on neutrophils. ANCA can induce generation of EVs from pre-activated, e.g., tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α primed neutrophils[72,76,77]. These particles increased CD54 surface expression and IL-6 and IL-8 production from human vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in vitro, suggesting that they can promote inflammation of the vessel wall[72]. ANCA induced EVs also contained tissue factor and may thus promote hypercoagulability and the increased rates of thrombosis observed in patients with ANCA disease[76,77].

TYPICAL HUS

Typical HUS is a complication of enteral infection with shiga toxin producing strains of Escherichia coli (STEC). EVs are highly elevated in patients with active systemic disease and platelet EV attach to leukocytes, most abundantly monocytes in peripheral blood[78-80]. Recent research shows that EVs are also generated from erythrocytes in this condition[81], a type of EV that can activate monocytes to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines[82]. Platelet monocyte complexes and EV generation from both can be induced by shiga toxin. These EVs contain tissue factor and can thereby contribute to the microthromboses characteristic of the disease[80]. They also bore activated complement constituents, namely C3 and C9[78]. Neutrophils phagocytosed them, a process that may further contribute to their activation, adhesion and vascular inflammation[78]. Both leukocyte and platelet EVs contain shiga toxin and significantly contribute to its spreading into tissues including podocytes and tubular epithelium in the kidney[83] thus contributing to toxicity. Whether or not shiga toxin increases or diminishes leukocyte lifespan appears to depend on experimental conditions in vitro[84]. In vivo, increased rates of both monocyte and neutrophil cell death were observed during STEC-HUS[79]. It is conceivable that shiga toxin transferred into the vascular wall by EVs will also influence vascular resident leukocytes[83].

THE ROLE OF EVS IN VASCULAR INFLAMMATION IN ATHEROSCLEROSIS

EVs are abundant within the atherosclerotic wall which may enhance their biologic functions[6]. EVs from human endarterectomy specimens have been isolated by serial centrifugation and analyzed by flow cytometry in comparison to material from macroscopically unaffected arteries[85,86]. A detailed analysis determined that most plaque EVs are of leukocyte origin, including 29% macrophage (CD14+), 15% lymphocyte (CD4+), 8% granulocyte (CD66b+) provenience[86]. No platelet, but erythrocyte and smooth muscle cell markers were detected in EVs from the plaque lysate, recent in vitro data providing first evidence of EV generation from smooth muscle cells in contact with pro-atherogenic lipids[87]. The analysis of plaque EV provenience was confirmed by subsequent studies including proteome analysis[38,88].

Mechanistic roles of EV action in atherosclerotic inflammation have mostly been ascribed to their protein content[50,51] including large cytoplasmic protein structures such as proteasomes and inflammasomes[89,90]. In addition, other constituents such as nucleic acids, notably microRNA[91,92], glycosylation pattern[93] and lipids[94] critically contribute to EV function in atherosclerosis[6,90,91]. Elevated systemic lipid levels and local deposition in the plaque makes EV lipids likely candidates for modulation of plaque development[95]. High levels of free cholesterol induce generation of phosphatidylserine and tissue factor rich EVs from human monocyte-derived macrophages, partly induced by caspase-3 mediated apoptosis. Systemically, circulating EV concentrations, mostly of platelet origin (CD41+) were significantly decreased after lipid apheresis in humans[96]. In renal impairment, lipoprotein function is markedly changed and protective functions are lost[97,98] making it a possible mediator of the observed functional shift in uremic EVs.

Patients with chronic kidney disease from any cause are at a markedly elevated risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality[97,99-101]. Medial calcification is characteristic of end-stage kidney disease[99,100]. Atherosclerotic plaques in moderate renal impairment are mostly found in the arterial intima and are histologically similar to lesions in normal renal function[102], a phenotype that has been replicated in animal models of atherosclerosis[103,104]. Given the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease already in the general population, the role of inflammatory leukocytes in atherosclerotic plaque development has been explored in human samples and atherosclerotic animal models with a variety of methods including histology, flow cytometry and live cell imaging[105-107]. Numbers of both adaptive and innate leukocytes in the vessel wall markedly increase during atherogenesis. With specific regards to renal impairment, current data on EV effects on innate and adaptive leukocyte populations prominent in atherosclerotic lesion formation will be reviewed.

THE ROLE OF EVS IN LEUKOCYTE INTERACTION WITH THE ENDOTHELIUM

When entering the vascular wall and again with growing intimal plaques, leukocytes come into close contact with endothelial cells. As a possible mechanism of proatherogenic EV effects on endothelial cells, CD40 ligand on human carotid plaque EVs is required for endothelial cell activation and neoangiogenesis by promotion of endothelial cell proliferation[88]. EVs isolated from human atherosclerotic plaques can transfer ICAM-1 to endothelial cells, thus facilitating leukocyte, mainly monocyte adhesion and transmigration[108]. They also expressed TNFα converting enzyme and plaque EVs that increase shedding of both TNFα and activated protein C from activated HUVECs[109]. The fact that monocyte and T cell EVs induced matrix metalloproteinase in synovial fibrocytes in rheumatoid arthritis suggests that this is a general EV property[110]. Neutrophil EVs increased endothelial cell IL-6 release in vitro[111]. T cell EVs generated both in in vitro and in vivo and EVs from patients with myocardial infarction decreased flow induced endothelial relaxation and downregulate eNOS expression[112,113]. As a potential positive feedback loop, NOS inhibition induces L-selectin and PSGL-1 expressing EVs from neutrophilic granulocytes seeded to HUVECs in vitro, that in turn increasing neutrophil transmigration[114]. Given NO inhibition by a range of uremic toxins[115], it is conceivable that these processes cooperate in renal impairment to impair vascular function.

Circulating EV counts are highly elevated during acute arterial thrombosis in a large number of studies. These have recently been reviewed and will therefore only been referred to in relation to vascular leukocytes in this manuscript[116-119]. However, it is of note that EV phosphatidylserine surface expression as a pro-thrombotic mediator was significantly increased in patients with the nephrotic syndrome of different etiologies[120] and the in vitro pro-coagulant effect of EVs from both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients was enhanced[46].

GRANULOCYTES

Neutrophilic granulocyte concentrations in peripheral blood and even more so, the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, are well-documented predictors of cardiovascular mortality[121,122]. This relationship is also highly significant in patients with end stage renal disease[123]. Recent animal data suggest that neutrophils mechanistically promote hypertension associated vascular damage and endothelial dysfunction[124]. Neutrophils are essential in early atherosclerotic plaque development, probably by NET formation[125]. They also generate a variety of EVs with pro- and anti-inflammatory functions[111,126-128]. Acting directly on the parental cell type, Annexin A1 present in neutrophil EVs inhibits neutrophil rolling, adhesion and migration in mice[126]. Neutrophil extravasation is promoted by close neutrophil contact with platelets and platelet EVs[12,13] (Figure 2). Both platelets and neutrophils generate long tethers during adhesion, some of which remain as free vesicles in the environment[129,130]. The essential role of platelet particles for directed neutrophil migration through the vessel wall is under active in vivo investigation by advancing imaging techniques[11-13,131,132]. Thrombus formation after plaque rupture directly activates neutrophils[133], a process that continues to be mechanistically explored in experimental arterial lesions[134]. Antagonizing either glycoprotein Ib or IIb IIIA on platelet EV inhibited neutrophil activation[135,136]. This may be relevant beyond acute thrombosis, as enhanced platelet activation by junctional adhesion molecule A deficiency[137] increased while deletion of glycoprotein Ib decreased myeloid cell activation and atherosclerotic lesion size[138]. These data suggest that platelet and platelet EV interactions with granulocytes promote also chronic atherosclerosis, in the absence of plaque rupture or thrombosis.

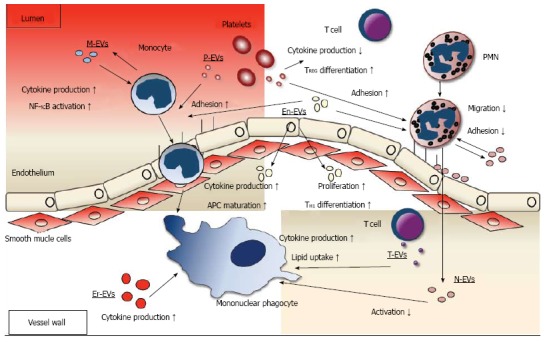

Figure 2.

Roles of extracellular vesicles in leukocyte function in the atherosclerotic plaque. Data on interaction of EVs with neutrophilic granulocytes, monocytes and mononuclear phagocytes and T lymphocytes is summarized. Regarding neutrophilic granuloctes (PMN), platelet EVs (P-EV) promote neutrophil (PMN) adhesion to the endothelium, neutrophil EVs (N-EV) mostly decrease adhesion and migration through the endothelium. Regarding monocytic cells, endothelial (En-EV) and P-EVs promote adhesion to the endothelium. Inside the plaque, En-EVs promote antigen presenting cell (APC) maturation and cytokine production and erythrocyte EVs (Er-EVs), monocyte EVs (M-EVs) and T cell EVs (T-EVs) increase cytokine production. T-EVs also increase lipid uptake. N-EVs suppress activation. Regarding T cells, P-EVs decrease cytokine production, En-EVs promote T cell proliferation and TH1 differentiation. EVs: Extracellular vesicles.

MONOCYTES AND MONONUCLEAR PHAGOCYTES

Myeloid phagocytes are central in atherosclerotic plaque development. They have a dual role with lipid uptake on the one hand, resulting in foam cell formation that can lead to cell death and thereby necrotic plaque cores and antigen presentation to cells of the adaptive system on the other hand[139-143]. In atherosclerosis enhanced by renal impairment, lesional macrophage content increased[104,144]. Angiotensin receptor I on myeloid cells[144-146] and IL-17[104] are instrumental in mediating this phenotype. Myeloid derived phagocytes in the atherosclerotic plaques differentiate from immigrating monocytes, but also proliferate locally, especially in mature plaques in which they are subject to the local milieu[147]. Both processes are influenced by EVs (Figure 2).

Monocyte adhesion to the endothelium in vitro was enhanced platelet EVs, induced by storage, thrombin or shear stress[148-150]. Platelet EVs also increased monocyte surface expression of adhesion molecules such as CD11a, CD11b integrins, platelet adhesion molecule 1 (CD31), CD33 lectin, and receptors such as CD14 and CD32 Fc receptor[148-150]. Endothelial EVs elicited by oxidized LDL or homocysteine from rat arterial endothelial cells contained high levels of heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) that increased monocyte adhesion in vitro[151]. In vivo in murine atherosclerosis, RANTES from platelet EVs coated the endothelium resulting in enhance monocyte adhesion[152].

Macrophage phenotype has a decisive role in plaque growth and stability of the lesion. In renal impairment, histologic analysis of the plaque showed that markers of M1 macrophage polarization were up-regulated with corresponding down-regulation of M2 markers[153]. Erythrocyte EVs that are found atherosclerotic plaques[86] induced TNFα production in monocytes in a CD40 ligand dependent fashion[82]. Platelet EVs induced secretion of cytokines that promote atherosclerotic plaque formation such as TNFα, IL-1β and IL-8 in a monocytic cell line in vitro[149]. IL-1β that is central atherogenesis[154] is itself contained in EVs released from platelets[155,156] and myeloid phagocytes[157-159]. However, cytokine induction by platelet EVs is not universal as small platelet EVs inhibited human monocyte-derived phagocyte TNFα and IL-10 secretion while TGFβ production was enhanced[160]. Human granulocyte EVs increased macrophage TGFβ1, but not IL-6 or IL-8 expression and blocked pro-inflammatory responses induced by zymosan or LPS. The authors also noted large donor variations in response to EVs suggesting that genetic factors may have a significant influence[127]. Annexin 1 is a potential mediator of the anti-inflammatory effects of granulocyte EVs[126]. Autocrine effects of monocytic EVs on monocyte differentiation and cytokine production varied with cell culture conditions. phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) elicited EVs from THP1 cells induced cell cycle arrest and macrophage differentiation TGFβ1 dependently[161] while human monocyte EVs increased TNFα and IL-6, release reactive oxygen species production and induced nuclear factor (NF)-κb activation[162]. Interestingly, NO, a pathway that is significantly inhibited in uremia, markedly enhanced EV release from RAW264 macrophages in vitro[163]. T lymphocyte EVs induced in both peripheral blood T lymphocytes and a human T cell line by phytohemagglutinin (PHA) and PMA increased TNFα, IL-1β and soluble IL-1 receptor a production in monocytes in a dose-dependent manner. This was not observed for EVs from unstimulated T cells[164,165]. Both TNFα and IL-1β generation were inhibited by HDL, connecting these studies directly to regulation of inflammation in the atherosclerotic plaque.

Regarding lipid phagocytosis, lipid and cholesterol content in peritoneal macrophages from atherosclerotic mice with renal impairment was significantly higher than in control animals[166] and the ability to take up labeled exogenous oxidized LDL particles significantly impaired in aortic macrophages[104]. This was attributed to decreased cholesterol efflux, mediated by decreased expression of the transporter ABCA1[166]. Platelet EVs increased uptake of oxidized LDL if present during macrophage differentiation in vitro. This protocol also increased CD14, CD36 and CD68 surface receptor expression[150]. In contrast, small platelet EVs with less than 50 nm diameter decreased lipid uptake via reduction of CD36 surface expression by enhanced ubiquitination[167] T lymphocyte EVs from PHA-activated human T lymphocytes increased cholesterol uptake in THP-1 cell and human monocyte derived macrophages[168].

Regarding antigen presentation, expression of the antigen presenting cell marker CD11c significantly increased in atherosclerotic aortas of mice with renal impairment[104]. T cell proliferation was significantly higher in their then aortas of atherosclerotic control mice. In addition, life cell imaging demonstrated that aortic T cell interactions with CD11c+ cells were significantly more frequent and longer in vessels from mice with renal impairment[104]. There is a large body of evidence for a role of EVs in antigen presenting cell function[6]. While many studies focused on tumor antigens, some may be directly relevant to atherosclerosis. Endothelial EVs from a human microvascular cell line induced by TNFα enhanced antigen presenting cell maturation, indicated by morphologic maturation, up-regulation of HLA-DR, CD83 and CCR7 and IL-6 secretion in a cell line and human plasmacytoid dendritic cell, but not in myeloid cells. While the stimulated cells were capable of inducing mixed lymphocyte reaction, interferon γ (IFNγ) was not induced by the co-incubation. Platelet and T cell EVs were used as controls and did not elicit this response[169]. Erythrocyte EVs enhanced T cell proliferation by modulation of monocyte maturation and induction of TNFα[82]. In a somewhat different setting, platelet EV recovered from thrombin-activated platelet supernatants induced HLA-DR expression in immature DCs during differentiation from human PBMC. This was mediated by CD40L[170], a protein that has been detected on human carotid plaque EVs[88]. Small EVs from resting platelets exerted a contrary effect and decreased HLA-DP, DQ, DR and CD80 expression during human PBMC differentiation[160]. While CD14 expression decreased similar to control cells, platelet EV also decreased endocytic capacity. Neutrophil EVs decreased immature dendritic cell phagocytic capacity and increased TGFβ release. Furthermore, LPS mediated maturation was severely impaired including surface marker expression, cytokine production and induction of T cell proliferation[171] extending the protective neutrophil effect from endothelium to monocyte derived phagocytes.

In summary, EVs of different cellular origins modulate mononuclear phagocyte functions that promote atherosclerosis in renal impairment.

LYMPHOCYTES

T cells are major modifiers of plaque formation among adaptive immune cells while the role for B cells is controversial[105-107]. B cell interaction with EVs can enhance or diminish B cell function[172,173], however, a link to atherosclerosis remains to be defined.

Among T helper cells, IFNγ-producing TH1 cells strongly promote atherosclerotic lesion formation. In the current experimental models, there appears to be no major role for TH2 cells in atherogenesis, while regulatory T cells and their marker cytokines such as IL-10 can attenuate lesion formation[105-107]. The impact of TH17 cells and their marker cytokine IL-17, which has a significant role in attraction of innate leukocytes such as neutrophilic granulocytes and monocytes[174], appears to be highly context-dependent[10,175]. Recent data show that proatherogenic lipoproteins can enhance TH17 polarization[176]. IL-17 production in T cells is markedly enhanced by environmental chemicals via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor[177-180]. Its ligands are well known uremic toxins[181,182]. Indeed, the IL-17 production was significantly increased in a cohort of patients with end stage renal disease[183]. Mechanistically, IL-17 was instrumental in increased myeloid cell accumulation and lesion burden in moderate renal impairment[104].

The effect of EVs on T cell function in vitro significantly varies depending on the cell of origin (Figure 2). Endothelial EVs enhanced CD4+ T cell proliferation in mixed lymphocyte reaction via modulation of dendritic cell maturation, resulting in enhanced TNFα and IFNγ secretion[169]. Similarly, EVs from TNFα-stimulated HUVECs induced TH1 differentiation in human PBMCs[184]. Erythrocyte EVs induced T cell proliferation indirectly via monocyte derived antigen presenting cell polarization. This stimulated the production of the pro-atherogenic cytokines IL-1β, IL-2, IL-7, IL-17 and IFNγ during co-culture of human PBMCs[82]. In contrast, small platelet EVs directly interacted with CD4+ T cells. They decreased IFNγ, TNFα and IL-6 production during polarization[185]. This was at least in part due to an increase in regulatory T cells induced by EV TGFβ. EVs from antigen presenting cells promote T cell priming[186,187]. In atherosclerosis, plasma and plaque EVs contain MHCI, MHCII and CD40L as EV surface antigens and it is therefore conceivable that these processes are also active during atherosclerosis in vivo[38,88].

CONCLUSION

Data on mechanisms how EVs modulate leukocyte adhesion, differentiation and vascular function in inflammation have greatly enhanced our understanding of these pathophysiologic processes. Experimental results suggest a number of mechanisms that enhance EV generation and modulate their function in renal patients. While analytic tools continue to be optimized and therapeutic options are limited to inhibition of platelet EVs at this point, EV counts start to serve as activity and prognostic markers in different conditions.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: We have no conflicts of interest regarding this work.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: September 2, 2015

First decision: November 27, 2015

Article in press: January 11, 2016

P- Reviewer: Fujigaki Y, Grignola JC, Paraskevas KI S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

References

- 1.Camussi G, Deregibus MC, Bruno S, Cantaluppi V, Biancone L. Exosomes/microvesicles as a mechanism of cell-to-cell communication. Kidney Int. 2010;78:838–848. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi DS, Kim DK, Kim YK, Gho YS. Proteomics, transcriptomics and lipidomics of exosomes and ectosomes. Proteomics. 2013;13:1554–1571. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colombo M, Raposo G, Théry C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, Zavec AB, Borràs FE, Buzas EI, Buzas K, Casal E, Cappello F, Carvalho J, et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27066. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.27066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Théry C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robbins PD, Morelli AE. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:195–208. doi: 10.1038/nri3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suades R, Padró T, Badimon L. The Role of Blood-Borne Microparticles in Inflammation and Hemostasis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015;41:590–606. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1556591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wick G, Romen M, Amberger A, Metzler B, Mayr M, Falkensammer G, Xu Q. Atherosclerosis, autoimmunity, and vascular-associated lymphoid tissue. FASEB J. 1997;11:1199–1207. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.13.9367355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bobryshev YV, Lord RS. Ultrastructural recognition of cells with dendritic cell morphology in human aortic intima. Contacting interactions of Vascular Dendritic Cells in athero-resistant and athero-prone areas of the normal aorta. Arch Histol Cytol. 1995;58:307–322. doi: 10.1679/aohc.58.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Vietinghoff S, Ley K. Interleukin 17 in vascular inflammation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:463–469. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt S, Moser M, Sperandio M. The molecular basis of leukocyte recruitment and its deficiencies. Mol Immunol. 2013;55:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marki A, Esko JD, Pries AR, Ley K. Role of the endothelial surface layer in neutrophil recruitment. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;98:503–515. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3MR0115-011R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams MR, Azcutia V, Newton G, Alcaide P, Luscinskas FW. Emerging mechanisms of neutrophil recruitment across endothelium. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Voisin MB, Nourshargh S. Neutrophil transmigration: emergence of an adhesive cascade within venular walls. J Innate Immun. 2013;5:336–347. doi: 10.1159/000346659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierson RN, Bromberg JS. Alloantibodies and Allograft Arteriosclerosis: Accelerated Adversity Ahead? Circ Res. 2015;117:398–400. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halloran PF, Reeve JP, Pereira AB, Hidalgo LG, Famulski KS. Antibody-mediated rejection, T cell-mediated rejection, and the injury-repair response: new insights from the Genome Canada studies of kidney transplant biopsies. Kidney Int. 2014;85:258–264. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Günthner T, Jankowski V, Kretschmer A, Nierhaus M, Van Der Giet M, Zidek W, Jankowski J. PROGRESS IN UREMIC TOXIN RESEARCH: Endothelium and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in the Context of Uremia. Semin Dial. 2009;22:428–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2009.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jourde-Chiche N, Dou L, Cerini C, Dignat-George F, Brunet P. Vascular incompetence in dialysis patients--protein-bound uremic toxins and endothelial dysfunction. Semin Dial. 2011;24:327–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2011.00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neven E, De Schutter TM, De Broe ME, D’Haese PC. Cell biological and physicochemical aspects of arterial calcification. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1166–1177. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stenvinkel P, Carrero JJ, Axelsson J, Lindholm B, Heimbürger O, Massy Z. Emerging biomarkers for evaluating cardiovascular risk in the chronic kidney disease patient: how do new pieces fit into the uremic puzzle? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:505–521. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03670807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amann K. Media calcification and intima calcification are distinct entities in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1599–1605. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02120508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlieper G, Schurgers L, Brandenburg V, Reutlingsperger C, Floege J. Vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease: an update. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:31–39. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Betjes MG. Immune cell dysfunction and inflammation in end-stage renal disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:255–265. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2013.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Druml W. Systemic consequences of acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014;20:613–619. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurts C, Panzer U, Anders HJ, Rees AJ. The immune system and kidney disease: basic concepts and clinical implications. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:738–753. doi: 10.1038/nri3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf P. The nature and significance of platelet products in human plasma. Br J Haematol. 1967;13:269–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1967.tb08741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim DK, Lee J, Kim SR, Choi DS, Yoon YJ, Kim JH, Go G, Nhung D, Hong K, Jang SC, et al. EVpedia: a community web portal for extracellular vesicles research. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:933–939. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gould SJ, Raposo G. As we wait: coping with an imperfect nomenclature for extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2013:2. doi: 10.3402/jev.v2i0.20389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi DS, Kim DK, Kim YK, Gho YS. Proteomics of extracellular vesicles: Exosomes and ectosomes. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2014;34:474–490. doi: 10.1002/mas.21420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pluskota E, Woody NM, Szpak D, Ballantyne CM, Soloviev DA, Simon DI, Plow EF. Expression, activation, and function of integrin alphaMbeta2 (Mac-1) on neutrophil-derived microparticles. Blood. 2008;112:2327–2335. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayers L, Kohler M, Harrison P, Sargent I, Dragovic R, Schaap M, Nieuwland R, Brooks SA, Ferry B. Measurement of circulating cell-derived microparticles by flow cytometry: sources of variability within the assay. Thromb Res. 2011;127:370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuana Y, Bertina RM, Osanto S. Pre-analytical and analytical issues in the analysis of blood microparticles. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105:396–408. doi: 10.1160/TH10-09-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Witwer KW, Buzás EI, Bemis LT, Bora A, Lässer C, Lötvall J, Nolte-’t Hoen EN, Piper MG, Sivaraman S, Skog J, et al. Standardization of sample collection, isolation and analysis methods in extracellular vesicle research. J Extracell Vesicles. 2013:2. doi: 10.3402/jev.v2i0.20360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN, Bobryshev YV. Extracellular vesicles and atherosclerotic disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:2697–2708. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1906-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaceb A, Martinez MC, Andriantsitohaina R. Extracellular vesicles: new players in cardiovascular diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;50:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Pol E, Böing AN, Harrison P, Sturk A, Nieuwland R. Classification, functions, and clinical relevance of extracellular vesicles. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:676–705. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.005983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayr M, Grainger D, Mayr U, Leroyer AS, Leseche G, Sidibe A, Herbin O, Yin X, Gomes A, Madhu B, et al. Proteomics, metabolomics, and immunomics on microparticles derived from human atherosclerotic plaques. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2009;2:379–388. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.108.842849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loyer X, Vion AC, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Microvesicles as cell-cell messengers in cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. 2014;114:345–353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erdbrügger U, Le TH. Extracellular Vesicles in Renal Diseases: More than Novel Biomarkers? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:12–26. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Faure V, Dou L, Sabatier F, Cerini C, Sampol J, Berland Y, Brunet P, Dignat-George F. Elevation of circulating endothelial microparticles in patients with chronic renal failure. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:566–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boulanger CM, Amabile N, Guérin AP, Pannier B, Leroyer AS, Mallat CN, Tedgui A, London GM. In vivo shear stress determines circulating levels of endothelial microparticles in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension. 2007;49:902–908. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000259667.22309.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amabile N, Guérin AP, Leroyer A, Mallat Z, Nguyen C, Boddaert J, London GM, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Circulating endothelial microparticles are associated with vascular dysfunction in patients with end-stage renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3381–3388. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ando M, Iwata A, Ozeki Y, Tsuchiya K, Akiba T, Nihei H. Circulating platelet-derived microparticles with procoagulant activity may be a potential cause of thrombosis in uremic patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1757–1763. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trappenburg MC, van Schilfgaarde M, Frerichs FC, Spronk HM, ten Cate H, de Fijter CW, Terpstra WE, Leyte A. Chronic renal failure is accompanied by endothelial activation and a large increase in microparticle numbers with reduced procoagulant capacity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1446–1453. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burton JO, Hamali HA, Singh R, Abbasian N, Parsons R, Patel AK, Goodall AH, Brunskill NJ. Elevated levels of procoagulant plasma microvesicles in dialysis patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daniel L, Fakhouri F, Joly D, Mouthon L, Nusbaum P, Grunfeld JP, Schifferli J, Guillevin L, Lesavre P, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L. Increase of circulating neutrophil and platelet microparticles during acute vasculitis and hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1416–1423. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qamri Z, Pelletier R, Foster J, Kumar S, Momani H, Ware K, Von Visger J, Satoskar A, Nadasdy T, Brodsky SV. Early posttransplant changes in circulating endothelial microparticles in patients with kidney transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2014;31:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen YL, Chen CH, Wallace CG, Wang HT, Yang CC, Yip HK. Levels of circulating microparticles in patients with chronic cardiorenal disease. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2015;22:247–256. doi: 10.5551/jat.26658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Angelillo-Scherrer A. Leukocyte-derived microparticles in vascular homeostasis. Circ Res. 2012;110:356–369. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.233403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morel O, Morel N, Jesel L, Freyssinet JM, Toti F. Microparticles: a critical component in the nexus between inflammation, immunity, and thrombosis. Semin Immunopathol. 2011;33:469–486. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Viera AJ, Mooberry M, Key NS. Microparticles in cardiovascular disease pathophysiology and outcomes. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2012;6:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amabile N, Rautou PE, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Microparticles: key protagonists in cardiovascular disorders. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2010;36:907–916. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arteaga RB, Chirinos JA, Soriano AO, Jy W, Horstman L, Jimenez JJ, Mendez A, Ferreira A, de Marchena E, Ahn YS. Endothelial microparticles and platelet and leukocyte activation in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nomura S, Inami N, Ozaki Y, Kagawa H, Fukuhara S. Significance of microparticles in progressive systemic sclerosis with interstitial pneumonia. Platelets. 2008;19:192–198. doi: 10.1080/09537100701882038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Preston RA, Jy W, Jimenez JJ, Mauro LM, Horstman LL, Valle M, Aime G, Ahn YS. Effects of severe hypertension on endothelial and platelet microparticles. Hypertension. 2003;41:211–217. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000049760.15764.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang PH, Huang SS, Chen YH, Lin CP, Chiang KH, Chen JS, Tsai HY, Lin FY, Chen JW, Lin SJ. Increased circulating CD31+/annexin V+ apoptotic microparticles and decreased circulating endothelial progenitor cell levels in hypertensive patients with microalbuminuria. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1655–1665. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833a4d0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martinez MC, Tual-Chalot S, Leonetti D, Andriantsitohaina R. Microparticles: targets and tools in cardiovascular disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Amabile N, Guérin AP, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM, London GM. Predictive value of circulating endothelial microparticles for cardiovascular mortality in end-stage renal failure: a pilot study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1873–1880. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eyre J, Burton JO, Saleem MA, Mathieson PW, Topham PS, Brunskill NJ. Monocyte- and endothelial-derived microparticles induce an inflammatory phenotype in human podocytes. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2011;119:e58–e66. doi: 10.1159/000329575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pisetsky DS, Ullal AJ, Gauley J, Ning TC. Microparticles as mediators and biomarkers of rheumatic disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:1737–1746. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Beyer C, Pisetsky DS. The role of microparticles in the pathogenesis of rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:21–29. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pereira J, Alfaro G, Goycoolea M, Quiroga T, Ocqueteau M, Massardo L, Pérez C, Sáez C, Panes O, Matus V, et al. Circulating platelet-derived microparticles in systemic lupus erythematosus. Association with increased thrombin generation and procoagulant state. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:94–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sellam J, Proulle V, Jüngel A, Ittah M, Miceli Richard C, Gottenberg JE, Toti F, Benessiano J, Gay S, Freyssinet JM, et al. Increased levels of circulating microparticles in primary Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis and relation with disease activity. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R156. doi: 10.1186/ar2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Willemze R, Bradford RL, Mooberry MJ, Roubey RA, Key NS. Plasma microparticle tissue factor activity in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies with and without clinical complications. Thromb Res. 2014;133:187–189. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Combes V, Simon AC, Grau GE, Arnoux D, Camoin L, Sabatier F, Mutin M, Sanmarco M, Sampol J, Dignat-George F. In vitro generation of endothelial microparticles and possible prothrombotic activity in patients with lupus anticoagulant. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:93–102. doi: 10.1172/JCI4985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nielsen CT, Østergaard O, Stener L, Iversen LV, Truedsson L, Gullstrand B, Jacobsen S, Heegaard NH. Increased IgG on cell-derived plasma microparticles in systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with autoantibodies and complement activation. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1227–1236. doi: 10.1002/art.34381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Østergaard O, Nielsen CT, Iversen LV, Tanassi JT, Knudsen S, Jacobsen S, Heegaard NH. Unique protein signature of circulating microparticles in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2680–2690. doi: 10.1002/art.38065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nielsen CT, Østergaard O, Rekvig OP, Sturfelt G, Jacobsen S, Heegaard NH. Galectin-3 binding protein links circulating microparticles with electron dense glomerular deposits in lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2015;24:1150–1160. doi: 10.1177/0961203315580146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brogan PA, Shah V, Brachet C, Harnden A, Mant D, Klein N, Dillon MJ. Endothelial and platelet microparticles in vasculitis of the young. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:927–936. doi: 10.1002/art.20199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Erdbruegger U, Grossheim M, Hertel B, Wyss K, Kirsch T, Woywodt A, Haller H, Haubitz M. Diagnostic role of endothelial microparticles in vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1820–1825. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hong Y, Eleftheriou D, Hussain AA, Price-Kuehne FE, Savage CO, Jayne D, Little MA, Salama AD, Klein NJ, Brogan PA. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies stimulate release of neutrophil microparticles. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:49–62. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011030298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bertram A, Lovric S, Engel A, Beese M, Wyss K, Hertel B, Park JK, Becker JU, Kegel J, Haller H, et al. Circulating ADAM17 Level Reflects Disease Activity in Proteinase-3 ANCA-Associated Vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2860–2870. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014050477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jennette JC, Falk RJ. Pathogenesis of antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-mediated disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10:463–473. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao L, David MZ, Hyjek E, Chang A, Meehan SM. M2 macrophage infiltrates in the early stages of ANCA-associated pauci-immune necrotizing GN. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:54–62. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03230314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Apostolidou E, Skendros P, Kambas K, Mitroulis I, Konstantinidis T, Chrysanthopoulou A, Nakos K, Tsironidou V, Koffa M, Boumpas DT, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps regulate IL-1β-mediated inflammation in familial Mediterranean fever. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:269–277. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Huang YM, Wang H, Wang C, Chen M, Zhao MH. C5a inducing tissue factor expressing microparticles and neutrophil extracellular traps promote hypercoagulability in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;10:2780–2790. doi: 10.1002/art.39239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ståhl AL, Sartz L, Karpman D. Complement activation on platelet-leukocyte complexes and microparticles in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli-induced hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood. 2011;117:5503–5513. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-309161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ge S, Hertel B, Emden SH, Beneke J, Menne J, Haller H, von Vietinghoff S. Microparticle generation and leucocyte death in Shiga toxin-mediated HUS. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2768–2775. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ståhl AL, Sartz L, Nelsson A, Békássy ZD, Karpman D. Shiga toxin and lipopolysaccharide induce platelet-leukocyte aggregates and tissue factor release, a thrombotic mechanism in hemolytic uremic syndrome. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arvidsson I, Ståhl AL, Hedström MM, Kristoffersson AC, Rylander C, Westman JS, Storry JR, Olsson ML, Karpman D. Shiga toxin-induced complement-mediated hemolysis and release of complement-coated red blood cell-derived microvesicles in hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Immunol. 2015;194:2309–2318. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Danesh A, Inglis HC, Jackman RP, Wu S, Deng X, Muench MO, Heitman JW, Norris PJ. Exosomes from red blood cell units bind to monocytes and induce proinflammatory cytokines, boosting T-cell responses in vitro. Blood. 2014;123:687–696. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-530469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ståhl AL, Arvidsson I, Johansson KE, Chromek M, Rebetz J, Loos S, Kristoffersson AC, Békássy ZD, Mörgelin M, Karpman D. A novel mechanism of bacterial toxin transfer within host blood cell-derived microvesicles. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004619. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tesh VL. The induction of apoptosis by Shiga toxins and ricin. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2012;357:137–178. doi: 10.1007/82_2011_155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mallat Z, Hugel B, Ohan J, Lesèche G, Freyssinet JM, Tedgui A. Shed membrane microparticles with procoagulant potential in human atherosclerotic plaques: a role for apoptosis in plaque thrombogenicity. Circulation. 1999;99:348–353. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.3.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Leroyer AS, Isobe H, Lesèche G, Castier Y, Wassef M, Mallat Z, Binder BR, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Cellular origins and thrombogenic activity of microparticles isolated from human atherosclerotic plaques. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:772–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Serrano-Pertierra E, Benavente L, Blanco-Gelaz MÁ, Fernández-Martín JL, Lahoz CH, Calleja S, López-Larrea C, Cernuda-Morollón E. Lysophosphatidylcholine Induces Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Membrane Vesiculation: Potential Role in Atherosclerosis through Caveolin-1 Regulation. JPB. 2014;7:332. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Leroyer AS, Rautou PE, Silvestre JS, Castier Y, Lesèche G, Devue C, Duriez M, Brandes RP, Lutgens E, Tedgui A, et al. CD40 ligand+ microparticles from human atherosclerotic plaques stimulate endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis a potential mechanism for intraplaque neovascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1302–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bochmann I, Ebstein F, Lehmann A, Wohlschlaeger J, Sixt SU, Kloetzel PM, Dahlmann B. T lymphocytes export proteasomes by way of microparticles: a possible mechanism for generation of extracellular proteasomes. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:59–68. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang JG, Williams JC, Davis BK, Jacobson K, Doerschuk CM, Ting JP, Mackman N. Monocytic microparticles activate endothelial cells in an IL-1β-dependent manner. Blood. 2011;118:2366–2374. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-330878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Noels H, Shagdarsuren E, Gan L, Denecke B, Hristov M, Köppel T, Jahantigh MN, Lutgens E, et al. Delivery of microRNA-126 by apoptotic bodies induces CXCL12-dependent vascular protection. Sci Signal. 2009;2:ra81. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ismail N, Wang Y, Dakhlallah D, Moldovan L, Agarwal K, Batte K, Shah P, Wisler J, Eubank TD, Tridandapani S, et al. Macrophage microvesicles induce macrophage differentiation and miR-223 transfer. Blood. 2013;121:984–995. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-374793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bilyy RO, Shkandina T, Tomin A, Muñoz LE, Franz S, Antonyuk V, Kit YY, Zirngibl M, Fürnrohr BG, Janko C, et al. Macrophages discriminate glycosylation patterns of apoptotic cell-derived microparticles. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:496–503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.273144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huber LC, Jüngel A, Distler JH, Moritz F, Gay RE, Michel BA, Pisetsky DS, Gay S, Distler O. The role of membrane lipids in the induction of macrophage apoptosis by microparticles. Apoptosis. 2007;12:363–374. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-0622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Miller YI, Choi SH, Fang L, Tsimikas S. Lipoprotein modification and macrophage uptake: role of pathologic cholesterol transport in atherogenesis. Subcell Biochem. 2010;51:229–251. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-8622-8_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Connolly KD, Willis GR, Datta DB, Ellins EA, Ladell K, Price DA, Guschina IA, Rees DA, James PE. Lipoprotein-apheresis reduces circulating microparticles in individuals with familial hypercholesterolemia. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:2064–2072. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M049726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kon V, Yang H, Fazio S. Residual Cardiovascular Risk in Chronic Kidney Disease: Role of High-density Lipoprotein. Arch Med Res. 2015;46:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pawlak K, Mysliwiec M, Pawlak D. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) plasma levels and oxLDL to LDL ratio - are they real oxidative stress markers in dialyzed patients? Life Sci. 2013;92:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kon V, Linton MF, Fazio S. Atherosclerosis in chronic kidney disease: the role of macrophages. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7:45–54. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2010.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schiffrin EL, Lipman ML, Mann JF. Chronic kidney disease: effects on the cardiovascular system. Circulation. 2007;116:85–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Campean V, Neureiter D, Varga I, Runk F, Reiman A, Garlichs C, Achenbach S, Nonnast-Daniel B, Amann K. Atherosclerosis and vascular calcification in chronic renal failure. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2005;28:280–289. doi: 10.1159/000090182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Buzello M, Törnig J, Faulhaber J, Ehmke H, Ritz E, Amann K. The apolipoprotein e knockout mouse: a model documenting accelerated atherogenesis in uremia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:311–316. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000045048.71975.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ge S, Hertel B, Koltsova EK, Sörensen-Zender I, Kielstein JT, Ley K, Haller H, von Vietinghoff S. Increased atherosclerotic lesion formation and vascular leukocyte accumulation in renal impairment are mediated by interleukin-17A. Circ Res. 2013;113:965–974. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Libby P, Lichtman AH, Hansson GK. Immune effector mechanisms implicated in atherosclerosis: from mice to humans. Immunity. 2013;38:1092–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sheedy FJ, Moore KJ. IL-1 signaling in atherosclerosis: sibling rivalry. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1030–1032. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Weber C, Noels H. Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med. 2011;17:1410–1422. doi: 10.1038/nm.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Rautou PE, Leroyer AS, Ramkhelawon B, Devue C, Duflaut D, Vion AC, Nalbone G, Castier Y, Leseche G, Lehoux S, et al. Microparticles from human atherosclerotic plaques promote endothelial ICAM-1-dependent monocyte adhesion and transendothelial migration. Circ Res. 2011;108:335–343. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Canault M, Leroyer AS, Peiretti F, Lesèche G, Tedgui A, Bonardo B, Alessi MC, Boulanger CM, Nalbone G. Microparticles of human atherosclerotic plaques enhance the shedding of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme/ADAM17 substrates, tumor necrosis factor and tumor necrosis factor receptor-1. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1713–1723. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Distler JH, Jüngel A, Huber LC, Seemayer CA, Reich CF, Gay RE, Michel BA, Fontana A, Gay S, Pisetsky DS, et al. The induction of matrix metalloproteinase and cytokine expression in synovial fibroblasts stimulated with immune cell microparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2892–2897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409781102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mesri M, Altieri DC. Endothelial cell activation by leukocyte microparticles. J Immunol. 1998;161:4382–4387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Martin S, Tesse A, Hugel B, Martínez MC, Morel O, Freyssinet JM, Andriantsitohaina R. Shed membrane particles from T lymphocytes impair endothelial function and regulate endothelial protein expression. Circulation. 2004;109:1653–1659. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124065.31211.6E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Boulanger CM, Scoazec A, Ebrahimian T, Henry P, Mathieu E, Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Circulating microparticles from patients with myocardial infarction cause endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2001;104:2649–2652. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.100516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nolan S, Dixon R, Norman K, Hellewell P, Ridger V. Nitric oxide regulates neutrophil migration through microparticle formation. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:265–273. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kielstein JT, Fliser D, Veldink H. PROGRESS IN UREMIC TOXIN RESEARCH: Asymmetric Dimethylarginine and Symmetric Dimethylarginine: Axis of Evil or Useful Alliance? Semin Dial. 2009;22:346–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2009.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lacroix R, Dubois C, Leroyer AS, Sabatier F, Dignat-George F. Revisited role of microparticles in arterial and venous thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11 Suppl 1:24–35. doi: 10.1111/jth.12268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shantsila E, Kamphuisen PW, Lip GY. Circulating microparticles in cardiovascular disease: implications for atherogenesis and atherothrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2358–2368. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Niccolai E, Emmi G, Squatrito D, Silvestri E, Emmi L, Amedei A, Prisco D. Microparticles: Bridging the Gap between Autoimmunity and Thrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015;41:413–422. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1549850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Vajen T, Mause SF, Koenen RR. Microvesicles from platelets: novel drivers of vascular inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114:228–236. doi: 10.1160/TH14-11-0962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Gao C, Xie R, Yu C, Wang Q, Shi F, Yao C, Xie R, Zhou J, Gilbert GE, Shi J. Procoagulant activity of erythrocytes and platelets through phosphatidylserine exposure and microparticles release in patients with nephrotic syndrome. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:681–689. doi: 10.1160/TH11-09-0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ruggiero C, Metter EJ, Cherubini A, Maggio M, Sen R, Najjar SS, Windham GB, Ble A, Senin U, Ferrucci L. White blood cell count and mortality in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1841–1850. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.von Vietinghoff S, Ley K. Homeostatic regulation of blood neutrophil counts. J Immunol. 2008;181:5183–5188. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Reddan DN, Klassen PS, Szczech LA, Coladonato JA, O’Shea S, Owen WF, Lowrie EG. White blood cells as a novel mortality predictor in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1167–1173. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Karbach S, Croxford AL, Oelze M, Schüler R, Minwegen D, Wegner J, Koukes L, Yogev N, Nikolaev A, Reißig S, et al. Interleukin 17 drives vascular inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and arterial hypertension in psoriasis-like skin disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2658–2668. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Warnatsch A, Ioannou M, Wang Q, Papayannopoulos V. Inflammation. Neutrophil extracellular traps license macrophages for cytokine production in atherosclerosis. Science. 2015;349:316–320. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Dalli J, Norling LV, Renshaw D, Cooper D, Leung KY, Perretti M. Annexin 1 mediates the rapid anti-inflammatory effects of neutrophil-derived microparticles. Blood. 2008;112:2512–2519. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gasser O, Schifferli JA. Activated polymorphonuclear neutrophils disseminate anti-inflammatory microparticles by ectocytosis. Blood. 2004;104:2543–2548. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Lőrincz ÁM, Schütte M, Timár CI, Veres DS, Kittel Á, McLeish KR, Merchant ML, Ligeti E. Functionally and morphologically distinct populations of extracellular vesicles produced by human neutrophilic granulocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;98:583–589. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3VMA1014-514R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sundd P, Gutierrez E, Koltsova EK, Kuwano Y, Fukuda S, Pospieszalska MK, Groisman A, Ley K. ‘Slings’ enable neutrophil rolling at high shear. Nature. 2012;488:399–403. doi: 10.1038/nature11248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Tersteeg C, Heijnen HF, Eckly A, Pasterkamp G, Urbanus RT, Maas C, Hoefer IE, Nieuwland R, Farndale RW, Gachet C, et al. FLow-induced PRotrusions (FLIPRs): a platelet-derived platform for the retrieval of microparticles by monocytes and neutrophils. Circ Res. 2014;114:780–791. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Hyun YM, Sumagin R, Sarangi PP, Lomakina E, Overstreet MG, Baker CM, Fowell DJ, Waugh RE, Sarelius IH, Kim M. Uropod elongation is a common final step in leukocyte extravasation through inflamed vessels. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1349–1362. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sreeramkumar V, Adrover JM, Ballesteros I, Cuartero MI, Rossaint J, Bilbao I, Nácher M, Pitaval C, Radovanovic I, Fukui Y, et al. Neutrophils scan for activated platelets to initiate inflammation. Science. 2014;346:1234–1238. doi: 10.1126/science.1256478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Döring Y, Drechsler M, Soehnlein O, Weber C. Neutrophils in atherosclerosis: from mice to man. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:288–295. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Totani L, Piccoli A, Dell’Elba G, Concetta A, Di Santo A, Martelli N, Federico L, Pamuklar Z, Smyth SS, Evangelista V. Phosphodiesterase type 4 blockade prevents platelet-mediated neutrophil recruitment at the site of vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1689–1696. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Lo SC, Hung CY, Lin DT, Peng HC, Huang TF. Involvement of platelet glycoprotein Ib in platelet microparticle mediated neutrophil activation. J Biomed Sci. 2006;13:787–796. doi: 10.1007/s11373-006-9107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Salanova B, Choi M, Rolle S, Wellner M, Luft FC, Kettritz R. Beta2-integrins and acquired glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa) receptors cooperate in NF-kappaB activation of human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27960–27969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704039200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Karshovska E, Zhao Z, Blanchet X, Schmitt MM, Bidzhekov K, Soehnlein O, von Hundelshausen P, Mattheij NJ, Cosemans JM, Megens RT, et al. Hyperreactivity of junctional adhesion molecule A-deficient platelets accelerates atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice. Circ Res. 2015;116:587–599. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Koltsova EK, Sundd P, Zarpellon A, Ouyang H, Mikulski Z, Zampolli A, Ruggeri ZM, Ley K. Genetic deletion of platelet glycoprotein Ib alpha but not its extracellular domain protects from atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 2014;112:1252–1263. doi: 10.1160/TH14-02-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Gautier EL, Jakubzick C, Randolph GJ. Regulation of the migration and survival of monocyte subsets by chemokine receptors and its relevance to atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1412–1418. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.180505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Packard RR, Maganto-García E, Gotsman I, Tabas I, Libby P, Lichtman AH. CD11c(+) dendritic cells maintain antigen processing, presentation capabilities, and CD4(+) T-cell priming efficacy under hypercholesterolemic conditions associated with atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2008;103:965–973. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.185793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Koltsova EK, Kim G, Lloyd KM, Saris CJ, von Vietinghoff S, Kronenberg M, Ley K. Interleukin-27 receptor limits atherosclerosis in Ldlr-/- mice. Circ Res. 2012;111:1274–1285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.277525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wu H, Gower RM, Wang H, Perrard XY, Ma R, Bullard DC, Burns AR, Paul A, Smith CW, Simon SI, et al. Functional role of CD11c+ monocytes in atherogenesis associated with hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2009;119:2708–2717. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.823740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Koltsova EK, Hedrick CC, Ley K. Myeloid cells in atherosclerosis: a delicate balance of anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory mechanisms. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24:371–380. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328363d298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Suganuma E, Zuo Y, Ayabe N, Ma J, Babaev VR, Linton MF, Fazio S, Ichikawa I, Fogo AB, Kon V. Antiatherogenic effects of angiotensin receptor antagonism in mild renal dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:433–441. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Yamamoto S, Kon V. Mechanisms for increased cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney dysfunction. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18:181–188. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328327b360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Yamamoto S, Yancey PG, Zuo Y, Ma LJ, Kaseda R, Fogo AB, Ichikawa I, Linton MF, Fazio S, Kon V. Macrophage polarization by angiotensin II-type 1 receptor aggravates renal injury-acceleration of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:2856–2864. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.237198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Robbins CS, Hilgendorf I, Weber GF, Theurl I, Iwamoto Y, Figueiredo JL, Gorbatov R, Sukhova GK, Gerhardt LM, Smyth D, et al. Local proliferation dominates lesional macrophage accumulation in atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1166–1172. doi: 10.1038/nm.3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Barry OP, Praticò D, Savani RC, FitzGerald GA. Modulation of monocyte-endothelial cell interactions by platelet microparticles. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:136–144. doi: 10.1172/JCI2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Nomura S, Tandon NN, Nakamura T, Cone J, Fukuhara S, Kambayashi J. High-shear-stress-induced activation of platelets and microparticles enhances expression of cell adhesion molecules in THP-1 and endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2001;158:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Vasina EM, Cauwenberghs S, Feijge MA, Heemskerk JW, Weber C, Koenen RR. Microparticles from apoptotic platelets promote resident macrophage differentiation. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e211. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2011.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Zhan R, Leng X, Liu X, Wang X, Gong J, Yan L, Wang L, Wang Y, Wang X, Qian LJ. Heat shock protein 70 is secreted from endothelial cells by a non-classical pathway involving exosomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;387:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Mause SF, von Hundelshausen P, Zernecke A, Koenen RR, Weber C. Platelet microparticles: a transcellular delivery system for RANTES promoting monocyte recruitment on endothelium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1512–1518. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000170133.43608.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Yamamoto S, Zhong J, Yancey PG, Zuo Y, Linton MF, Fazio S, Yang H, Narita I, Kon V. Atherosclerosis following renal injury is ameliorated by pioglitazone and losartan via macrophage phenotype. Atherosclerosis. 2015;242:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Zimmer S, Grebe A, Latz E. Danger signaling in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2015;116:323–340. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.301135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Brown GT, McIntyre TM. Lipopolysaccharide signaling without a nucleus: kinase cascades stimulate platelet shedding of proinflammatory IL-1β-rich microparticles. J Immunol. 2011;186:5489–5496. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Boilard E, Nigrovic PA, Larabee K, Watts GF, Coblyn JS, Weinblatt ME, Massarotti EM, Remold-O’Donnell E, Farndale RW, Ware J, et al. Platelets amplify inflammation in arthritis via collagen-dependent microparticle production. Science. 2010;327:580–583. doi: 10.1126/science.1181928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]