Abstract

Aim:

During the last decades, number of food poisoning cases due to Campylobacter occurred, immensely. After poultry, raw milk acts as a second main source of Campylobacter. Therefore, the present study was undertaken to detect the prevalence of Campylobacters in milk and milk products and to know the antibiotic sensitivity and virulence gene profile of Campylobacter spp. in Anand city, Gujarat, India.

Material and Methods:

A total of 240 samples (85 buffalo milk, 65 cow milk, 30 cheese, 30 ice-cream and 30 paneer) were collected from the different collection points in Anand city. The samples were processed by microbiological culture method, and presumptive isolates were further confirmed by genus and species-specific polymerase chain reaction using previously reported primer. The isolates were further subjected to antibiotic susceptibility assay and virulence gene detection.

Result:

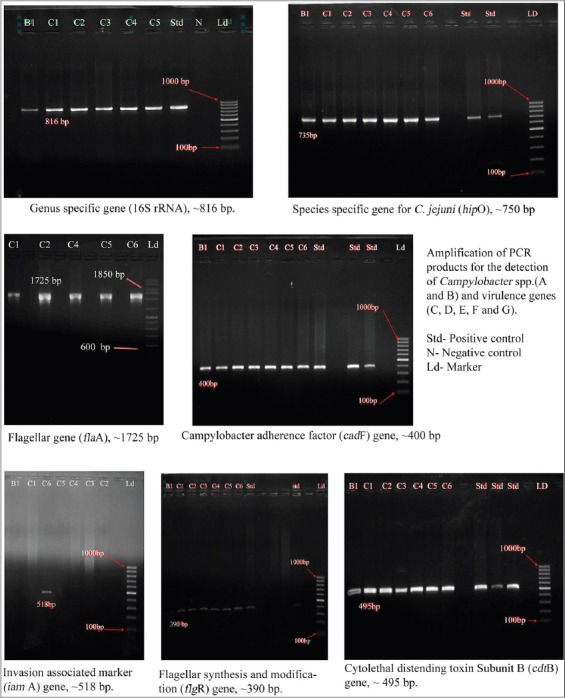

Campylobacter species were detected in 7 (2.91%) raw milk samples whereas none of the milk product was positive. All the isolate identified were Campylobacter jejuni. Most of the isolates showed resistance against nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, and tetracyclin. All the isolates have three virulence genes cadF, cdtB and flgR whereas only one isolate was positive for iamA gene and 6 isolates were positive for fla gene.

Conclusion:

The presence of Campylobacter in raw milk indicates that raw milk consumption is hazardous for human being and proper pasteurization of milk and adaptation of hygienic condition will be necessary to protect the consumer from this zoonotic pathogen.

Keywords: antibiotic susceptibility, Campylobacter jejuni, polymerase chain reaction, virulence gene

Introduction

An infection that occurs due to consumption of food of animal origin is an important public health problem in all over the world [1]. Animal products that are mainly used for human consumption are meat of different animal, milk and the products that are made from them. In all these, milk and milk products are mainly used as a dietary source by Indians [2]. Raw milk acts as the main source for various pathogens such as Escherichia coli, Mycobacterium bovis, Listeria monocytogenes, Campylobacter, Brucella and Salmonella [3]. In all these, Campylobacters the leading cause of zoonotic infections in many countries and the public health burden due to Campylobacteriosis is increasing day to day [4]. It is a gastrointestinal disorder that mainly affects infants, elderly people, patients with underlying disease and immunocompromised individuals. Campylobacteriosis is usually a self-limited disease, and antimicrobial therapy is not generally indicated [5,6].

The family Campylobacteraceae consists of four genera, comprising Campylobacter, Arcobacter, Dehalospirilum, and Sulfurospirilum. Under this genus campylobacter consists of 32 species and 13 subspecies [7]. They are motile, curved S- or spiral shaped Gram-negative rods, 0.2-0.8 μm wide and 0.5-5 μm long [7]. In all the species, Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli are most important from food safety point of view and causes enteritis in domestic animal and human being [4,6].

Campylobacters are inhabitants in the intestinal tract of a wide variety of wild and domestic animals, especially birds [8]. Inadequately cooked meat, particularly poultry, unpasteurized milk, contaminated drinking water, ready to eat food products, direct contact with animals, fecal runoff of domestic animals and birds contaminating surface water act as main source of organism [9-11]. Raw milk is primarily to be contaminated by bovine feces. However, direct contamination of milk as a consequence of mastitis also occurs [12].

It causes diarrhea and abortion in animals. In human being, the gastroenteritis due to Campylobacter ranges from mild to severe diarrheal disease. Instead of diarrhea (often bloody diarrhea), other symptoms are cramping, abdominal pain and fever within 2-5 days after exposure to the organism, with symptoms typically lasting 1 week [5]. Complications that occur due to Campylobacter are Guillain-Barre syndrome, reactive arthritis, hemolytic uraemic syndrome and meningitis, etc. [13]. Though infections due to C. jejuni are rare, and most patients do not need specific interventions. However, emergence of antimicrobial resistant Campylobacters had increased the chances of increased invasive illness [14]. The increased prevalence of this resistant campylobacter has been linked to the illegitimate use of antimicrobials in food animals, animal feeds and flock treatment of animals rather than the individual approach [15].

Despite the increased recovery of Campylobacters as a food borne pathogen, the specific virulence and pathogenic mechanisms by which microaerophilic Campylobacter species causes infection are still poorly understood [16]. The putative virulence factor for adhesion and invasion of epithelial cells, toxin production, and flagellar motility are thought to be important virulence mechanisms[17]. But, different studies have indicated that different virulence marker could play a role of colonization, adherence, and invasion of Campylobacter spp. in the animal and human being.

Campylobacter infection are sporadic in nature and have worldwide occurrence [18-23]. In UK, it is the principal cause of gastroenteritis while in United States; it is fifth domestically acquired foodborne infection [24]. It is the most common notifiable foodborne disease in Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Italy, Sweden, and Norway [25,26]. Due to less information about Campylobacter in milk and milk products in India, this study was projected to characterize the Campylobacter isolates from milk and milk products to know the prevalence and antibiotic resistance pattern of Campylobacter spp. in Anand city, Gujarat, India.

Material and Methods

Ethical approval

The study entailed the collection of milk samples from farmer’s cattle milk from collection points, retail shop and vendor. Ethical approval was obtained Ethical Review Committee, Veterinary Science College, AAU, Anand, Gujarat. Farmers, person in charge of units and shops were informed about study and verbal consent was taken before collection of samples.

Source of experimental samples

A total of 240 samples comprising raw milk (85 buffalo and 75 cow milk), cheese (30), ice-cream (30) and paneer (30) were collected from different collection points, retail shops and vendors in and around the Anand city in sterilized container in ice pack and processed within 2 h.

Enrichment and plating of milk and milk product samples

Samples were processed to isolate the Campylobacter spp. as per the method described by Salihu et al. [27]. In brief, pH of milk samples was adjusted at 7.5 and 20 ml of milk was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min. at 4°C. The pellet was suspended in 45 ml of Preston enrichment broth base containing Preston enrichment supplement, Campylobacter growth supplement (HiMedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India) and 5% (v/v) defibrinated sheep blood in 100 ml sterile screw cap flask. For dairy product samples, 25 g of samples were homogenized in normal saline and transferred to 225 ml of Preston enrichment broth base containing Campylobacter selective supplement IV (HiMedia Laboratories, Mumbai, India) and 5% (v/v) defibrinated sheep blood, mixed properly and incubated at microaerophilic environment (85% N2, 5%O2 and 10% CO2) in water jacketed CO2 incubator (NUAIRE, Polymouth, MN, USA) at 42°C for 42 h. After enrichment culture, a loopful of enriched culture was streaked on blood free charcoal cefoperazone deoxycholate agar medium plates [27]. For selective isolation typical due drop like colonies were isolated on blood agar with 5% defibrinated sheep blood to obtain pure cultures. The inoculated plates were incubated at microaerophilic environment (85% N2, 5%O2 and 10% CO2) at 42°C for 48 h.

Presumptive identification of isolates

Three or four Campylobacter-like colonies were picked from each plate and subjected to gram staining and oxidase, catalase, indoxyl acetate, hippurate hydrolysis test, H2S production and nitrate reduction test [21,28].

DNA extraction

The DNA was extracted by heat and snap chilling method. The two to three colonies of fresh bacterial growth on culture medium was collected, suspended in nuclease-free demonized water and heated at 95°C for 10 min. The samples were cooled immediately and centrifuge for 5 min at room temperature. The supernatant was separated, and 3 µl was used as DNA template.

Confirmation and species identification of isolates using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

The biochemically identified isolates were further employed for confirmation as genus Campylobacter and species C. jejuni and C. coli, by polymerase chain reaction amplifying specific target gene using genus and species-specific oligonucleotide primers. The primer sequence and size of target PCR product is shown in Table-1. The DNA amplification for each primer pair was carried out in a Applied Biosystems 2720 Thermal Cycler in 25 µl reaction containing 3 µl of DNA template, 12.5 µl mastermix (Thermo Scientific, USA) (containing 0.05 unit/µl Taq DNA Polymerase, reaction buffer, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM of each dNTP), 10 pmole of each forward and reverse primer (10 pmole/µl), and 7.5 ml nuclease free water with positive and negative control. The control strains of C. jejuni and C. coli isolates in our department were used for positive control whereas DNase free distilled water was used for negative control. The cycling protocol for the genus confirmation was standardized to set the PCR assay as initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles with denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 53°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 30 s and final extension at 72°C for 10 min. For hippuricase (hipO) gene of Campylobacter jejuni, cycling condition was optimized to initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles with denaturation at 95°C for 45 s, annealing at 51°C for 45 s and extension at 72°C for 45 s and final extension at 72°C for 7 min and for asperkinase A (askA) gene of C. coli cycling condition was optimized to initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles with denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 53°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 30 s and final extension at 72°C for 7 min. On completion of the reaction, the amplified products were held briefly at 4°C. Amplification of the PCR products were detected by electrophoresis in 1.5% agarose gel with ethidium bromide (10 µg/ml) in 0.5X TBE buffer (Sigma, USA) at 100 V for 40 min and documented in G: BOXF3 (SynGene, USA).

Table 1.

List of the genus and species specific primers.

| Gene name | Primer Sequence | Target gene | Amplicon size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C412F | GGATGACACTTTTCGGAGC | Campylobacter genus 16S rRNA | 816 | 78 |

| C1228R | CATTGTAGCACGTGTGTC | |||

| Hip O1 | AGCTAGCTTCGCATAATAACTTG | C. jejuni Hippurase Gene | 735 | 79 |

| Hip O2 | GAAGAGGGTTTGGGTGGT | |||

| CC1 | GGTATGATTTCTACAAAGCGAG | C. coli Asperkinase gene | 500 | 79 |

| CC2 | ATAAAAAGACTATCGTCGCGT |

C. coli=Campylobacter coli, C. jejuni=Campylobacter jejuni

In vitro antimicrobial drug resistance pattern

All the Campylobacter isolates were subjected for antibiotic susceptibility test by Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method according to the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [29] for seven antibiotics as ciprofloxacin (5 mcg), chloramphenicol (30 mcg), nalidixic acid (30 mcg), erythromycin (15 mcg), gentamicin (10 mcg), Streptomycin sulphate (30 mcg) and Tetracycline (30 mcg) as suggested by External Quality Assurance System [30]. Isolates were grown on nutrient broth No. 2 at 37°C for 24 h. The individual broth culture was then smeared on the surface of Mueller-Hinton agar (Hi Media) supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood with the help of sterile cotton swab. The plates were allowed to dry for few minutes. Antibiotic disc was placed on the agar surface within 15 min of inoculation of the plates. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C. Sensitivity or resistance of an isolate for a particular antibiotic was determined by measuring the diameter of the zone of growth inhibition. The result was interpreted as sensitive, intermediate or resistant by comparing with manufacturer’s instructions. Culture of ATCC 33560 was used to check the quality for antibiotic sensitivity test.

Virulence gene characterization of Campylobacter isolates

The confirmed isolates of Campylobacter species were characterized for in vitro detection of virulence genes by PCR for five well-known virulence gene encoding flagellin gene (flaA) [31], campylobacter adherence gene (cadF) [32,33], invasion associated marker, iamA [34], flagellar synthesis and modification, flgR [16] and cytolethal distending toxin subunit B gene (cdtB) [35]. The details of primers for target virulence genes and PCR conditions are described in Table-2 and 3, respectively. The DNA of virulence gene positive control strains available in our department was used in PCR for detection of virulence genes while for negative control DNA template was replaced with nuclease-free distilled water. The positive control PCR revealed PCR product of appropriate size and in a negative control, no product was amplified.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide sequence of virulence genes.

| Target gene | Primer | Primer Sequence (5’→3’) | Amplicon size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flagellin gene | fla 1 | GGATTTCGTATTAACACAAATGGTGC | 1725 | 80 |

| fla 2 | CTGTAGTAATCTTAAAACATTTTG | |||

| Campylobacter adherence gene | cad F | TTGAAGGTAATTTAGATATG | 400 | 66 |

| cad R | CTAATACCTAAAGTTGAAAC | |||

| Invasion associated marker | iam F | GCGCAAAATATTATCACCC | 518 | 34 |

| iam R | TTCACGACTACTATGCGG | |||

| Flagellar synthesis and modification, flgR | JL 1225 | GAGCGTTTAGAATGGGTGTG | 390 | 16 |

| JL 1226 | GCCAGGAATTGATGGCATAG | |||

| Cytolethal distending toxin SubunitB gene | CdtB-F | GTTGGCACTTGGAATTTGCAAGGC | 495 | 74 |

| CdtB-R | GTTAAAATCCCCTGCTATCAACCA |

Table 3.

PCR cyclic condition of virulence genes.

| Gene | Initial denaturation | 35 cycles | Final extension | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturation | Annealing | Extension | |||

| Flagellin gene | 94°C | 94°C | 52°C | 72°C | 72°C |

| 5 min | 45 s | 45 s | 1 min | 10 min | |

| Campylobacter adherence gene | 94°C | 94°C | 45°C | 72°C | 72°C |

| 5 min | 1 min | 45 s | 1 min | 8 min | |

| Invasion associated marker | 94°C | 94°C | 52°C | 72°C | 72°C |

| 5 min | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min | 5 min | |

| Flagellar synthesis and modification, flgR | 95°C | 95°C | 54°C | 72°C | 72°C |

| 5 min | 1 min | 1 min | 1 min | 5 min | |

| Cytolethal distending toxin subunit B gene | 95°C | 95°C | 57°C | 72°C | 72°C |

| 5 min | 30 s | 30 s | 30 s | 10 min | |

PCR=Polymerase chain reaction

Results and Discussion

Cultural plates that show typical dew drop like colonies were identified as Campylobacter. All the isolates were Gram-negative, spiral, curved or S-shaped rods, motile with characteristic darting screw type motility and showed oxidase and catalase positive reactions. All the isolates were positive for hippurate hydrolysis, indoxyl acetate, H2S production, nitrate reduction and growth were further confirmed by genus-specific PCR by generating 816 bp of amplicon 16S rRNA sequence and species specific PCR by targeting 735 bp and 500 bp amplicon of hippurase (hipO) and asperkinase (askA) gene for C. jejuni and C. coli, respectively.

The overall 2.91% prevalence of Campylobacter was observed in total of 240 samples processed comprising 150 raw milk, 30 cheese, 30 paneer and 30 ice-cream. All the positive samples were obtained from raw milk (4.66%), none of the milk product sample was found positive for Campylobacter. All the seven Campylobacter isolates were identified as C. jejuni (100%) by species-specific PCR indicating that this species is distributed widely in the study area. The findings of the present study is concurrent with reports of Kazemeini et al. [36], Wysok et al. [37] and Rahimi et al.[38] where they observed almost similar prevalence rate i.e. 2.5%, 4.6% and 2.32%, respectively. A lower prevalence rate of 1.5% and 1.41% was observed by Lovett et al. [39] in Cincinnati, Ohio, Canada and Elango et al. [40] in Chennai, India whereas some authors have not detected campylobacters in milk samples [41,42]. On the other hand, higher prevalence rate of 34%, 12.3%, 10.2%, 61%, 12.5%, 12.5%, 66.8%, 3.06% and 8.07% was observed by Wicker et al. [43], Jayarao et al. [44], Hussain et al. [10], Martin et al. [45], Khanzadi et al. [46], Giacometti et al. [47], Mabotel et al. [48], Serraino et al. [49] and Giacometti et al. [50], respectively.

In the case of milk products, we did not found any positive sample which was concurrent with the study of Singh et al. [42] who could not detect campylobacters in cheese. In contrast to this Giacometti et al. [50] and Jain and Shrivastava [51] found the prevalence rate of 5.0% and 18.33% from traditional cheese while Vaishnavi et al. [52] identified the prevalence of 17.2% from paneer.

Although there is significant variation of the presence of Campylobacter in different food products as reported by different workers, milk act as a second main source of Campylobacter. The present study revealed that Campylobacter could be mainly transmitted through milk in comparison to milk products. The possible reason behind this may be destruction of an organism during the processing of milk products. It is mainly destroyed during the boiling of milk, so there are less chances of contamination of this pathogen in milk products. Contamination of milk products is only possible because of unhygienic conditions during the preparation of milk products.

In the present study, all the Campylobacter isolates were resistant to Nalidixic acid (100%), whereas 6 (85.71%) and 1 (14.29%) isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin and tetracyclin, respectively. One isolate was intermediate while 5 (71.42%) isolates were sensitive to Tetracycline. All the isolates were sensitive for chloramphenicol, gentamicin, streptomycin sulfate and erythromycin. Only one isolates was sensitive for ciprofloxacin. The result is also in collaboration with Chatur et al. [53] who observed extremely high resistance of C. jejuni isolates to nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin in study area. The presence of quinolone resistant campylobacter strains in the study area indicates the mutation in the gyrase subunit A gene that could be caused due to the treatment of animal with quinolones or their use in animal feed. As environment and water could act as the main source of contamination of milk due to unhygienic conditions, the presence of Campylobacter spp. from other animal species cannot be overruled. Looking into the increasing importance of Campylobacter sporadic outbreaks, this study suggests regular surveillance program for the detection and understanding the behavior of campylobacters. In Poland, Wysok et al. [37] and in Iran, Rahimi et al. [38] also obtained the same resistance pattern in their study while Murphy et al. [54] and Bopp et al. [55] found higher resistance against tetracycline.

In vitro detection of virulence genes revealed presence of Cad, CdtB and flgR genes in all the isolates while only one isolate was positive for iamA gene and 6 isolates were positive for flaA gene (Figure-1). The Flagellin gene encodes for a flagella protein that is responsible for motility, colonization of gastrointestinal tract and invasion of host cells [31]. Wegmuller et al. [56] detected only 6 (6.5%) positive samples out of 93 samples in their study which was much lower in comparison to present study. This could be because of different primers used in this and present study. Campylobacter species are motile by means of a single polar, unsheathed flagellum at one or both ends of the organism. Two genes, flaA and flaB, that are involved in the expression of the flagellar filament have been identified in C. jejuni [57,58] and C. coli [59]. In both species, the two genes are arranged head-to-tail in the same direction, separated by 174 bp having separate promoter region. In strains like C. jejuni, 81116, only flaA is expressed [58], whereas in C. coli VC167, some flaB is also expressed [59]. The flaA mutant strains of C. jejuni has shown reduced motility and colonization [60,61]. The PCR can detect either one fla gene or two, depending on which primers are used. The primers are designed to bind strongly to conserved sequences, but the sequence in between the primers is highly variable and the primers were found to work for C. coli and C. upsaliensis as well [62]. Though, primer strongly binds in conserved sequences, we could not amplify the approximate 1725 bp PCR product of flaA gene using the cited primers in one isolate (C3) obtained from cow raw milk. The mutation could have occurred in primer binding site on flaA gene may be due to sub culturing, or already mutant C. jejuni isolate in milk sample.

Figure-1.

Amplification of PCR products for the detection of Campylobacter spp. and virulence genes

Presence of campylobacter adherence factor in all the isolates was in conformity with the report of Elango et al. [40] while it was higher as compared to the finding of Khanzadi et al. [46]. They observed the 15.5% occurrence of cadF gene among all Campylobacter isolates and only 8% in C. jejuni isolates. The results of present study agree with the data obtained by other authors, who examined and found 100% prevalence of Cad gene in Campylobacter isolates derived from different sources [63-66].

Among 7 isolates studied only one (14.28%) isolates were positive for the presence of iamA gene and yielded the DNA fragment of 518bp. There was no any previous study for the presence of iamA gene in Campylobacter isolates that were isolated from milk but this gene was reported by different authors in those Campylobacter isolates that were obtained from meat or other sources [67-70].

All the seven isolates were positive for the presence of flgR gene and yielded the DNA fragment of 390bp. No any study was conducted previously for the presence of flgR gene in Campylobacter isolates isolated from milk. This gene encodes the signal-transduction regulatory protein responsible for flagellar synthesis and modification as a gene in response regulator of a two component system (FlgR/S) and described by different authors responsible for phase variation is a mechanism whereby the bacteria can modify the antigenic make-up of its surface to evade the host immune system or adapt to new hosts or environments [71-73].

All the seven isolates were positive for the presence of cdtB gene and yielded the DNA fragment of 495bp. The absence of reports of screening of the Campylobacter isolates isolated from milk and milk products for the presence of cdtB gene was the limitation for us to compare the result of the occurrence of cdtB gene in this study. On the contrary, most of authors have detected this gene in Campylobacter isolates isolated from other food and clinical samples [74,75] whereas it has also been detected in cattle beef and fecal samples [74,76,77].

Conclusions

Considering the zoonotic potential of this organism, in this study, we conclude that the raw milk and milk products act as the main source of Campylobacter, which is the leading cause of gastroenteritis worldwide. Due to its thermophilic nature, potential pathogenic character and the capability to grow in milk, monitoring and surveillance of this pathogen in raw milk and milk product should be necessary. It has been necessary to increase the activities for development of the concept for production of safe milk; maintain the hygienic condition at farm and processing unit and pasteurization of milk to protect the consumer.

Author’s Contributions

SM supervised the overall research work. YAC and SM participated in sampling, analysis of samples and made available relevant literatures. MNB and JBN participated in draft and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We express sincere thanks to College of Veterinary Science and A. H., Anand Agricultural University for providing infrastructure and Government of Gujarat state for providing fund for the project.

Competing Interests

Authors declares that they don’t have any competing interests.

References

- 1.van de Venter T. Emerging food-borne diseases: A global responsibility. Food Nutr. Agric. 2000;26:4–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kishor S. B, Gabhane D. Study of Impact of food inflation on middle class consumer's household consumption of milk with reference to Thane city. Abhinav Natl. Mon. Refereed J. Res. Commer. Managg. 2012;1(4):54–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leedom J. M. Milk of non human origin and infectious diseases in humans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;43(5):610–615. doi: 10.1086/507035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for Diseases Control and Prevention. Preliminary foodnet data on the incidence of infection with pathogen transmitted commonly through food- 10 states, United State 2007. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2007;57:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray P. R, Baron E. J, Jorgensen J. H, Landry M. L, Pfaller M.A, editors. Manualof Clinical Microbiology. 9th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press, American Society of Microbiology; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nachamkin I, Szymanski C.M, Blaser M.J. Campylobacter. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press, American Society for Microbiology; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vandamme P, Debruyne L, De Brandt E, Falsen E. Reclassification of Bacteroidesureolyticus as Campylobacter ureolyticus comb. nov., and emended description of the genus Campylobacter. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010;60:2016–2022. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.017152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altekruse S, Perez-Perez G.I. Campylobacter jejuni and related organisms. In: Riemann H.P, Cliver D.O, editors. Foodborne Infections and Intoxications. 3rd ed. London: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 259–287. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humphrey T.J, Hart R.J.C. Campylobacter and Salmonella contamination of unpasteurised cow's milk on sale to the public. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1988;65:463–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1988.tb01918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussain I, Mahmood M.S, Akhtar M, Khan A. Prevalence of Campylobacter species in meat, milk and other food commodities in Pakistan. Food Microbiol. 2007;24:219–222. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whyte P, McGill K, Cowley D, Madden R. H, Moran L, Scates P, Carroll C, O'Leary A, Fanning S, Collins J. D, McNamara E, Moore J. E, Cormican M. Occurrence of Campylobacter in retail foods in Ireland. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004;95:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson P.J, Vogt R.L, Brondum T, Patton C.M. Isolation of Campylobacter jejuni from milk during an outbreak of. Campylobacteriosis. J. Infect. Dis. 1984;150:789–797. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.5.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kopyta I, Wardak S. Campylobacter jejuni infection in patient with Guillain Barre syndrome- Clinical case report. Med. Dosw. Microbiol. 2008;60(1):59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helms M, Simonsen J, Olsen K.E, Molbak K. Adverse health events associates with antimicrobial drug resistance in Campylobacter spp.: A registry based cohort study. J. Infect. Dis. 2005;191(7):1050–1055. doi: 10.1086/428453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall B.M, Levy S.B. Food Animals and Antimicrobials: Impacts on Human Health. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011;24(4):718–733. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson D.L, Rathinam V.A, Qi W, Wick L.M, Landgraf J, Bell J.A, Plovanich-Jones A, Parrish J, Finley R.L, Mansfield L.S, Linz J.E. Genetic diversity in Campylobacter jejuni is associated with differential colonization of broiler chickens and C57BL/6J IL10-deficient mice. Microbiology. 2010;156(7):2046–2057. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.035717-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young K.T, Davis L.M, DiRita V.J. Campylobacter jejuni: Molecular biology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbial. 2007;5:665–679. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alary M, Nadeau D. An outbreak of Campylobacter enteritis associated with a community water supply. Can. J. Public Health. 1990;81:268–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson Y, Dejong B, Studahl A. Waterborne Campylobacter in Sweden - the cost of an outbreak. Water Sci. Technol. 1997;35:11–14. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itoh T, Saito K, Maruyama T, Sakai S, Ohashi M, Oka A. An outbreak of acute enteritis due to Campylobacter fetus subspecies jejuni at a nursery school of Tokyo. Microbiol. Immunol. 1980;24:371–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1980.tb02841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzgerald C, Nachamkin I. Campylobacter and Arcobacter. In: Manualof Clinical Microbiology. Washington, DC: ASMPress; 2007. pp. 933–946. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millson M, Bokhout M, Carlson J, Spielberg L, Aldis R, Borczyk A, Lior H. An outbreak of Campylobacter jejuni gastroenteritis linked to melt water contamination of a municipal well. Can. J. Public Health. 1991;82:27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rautelin H, Hanninen M.L. Campylobacters: The most common bacterial enteropathogens in the Nordic countries. Ann. Med. 2000;32:440–445. doi: 10.3109/07853890009002018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CDC. CDC Estimates of Foodborne Illness in the United States. 2011. [Accessed on 30.09.2013]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/2011-foodborne-estimates.html .

- 25.Taylor D.E, Chang N. In vitro susceptibilities of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli to azithromycin and erythromycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1917–1918. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ikram R, Chambers S, Mitchell P, Brieseman M.A, Ikam O.H. A case control study to determine risk factor for Campylobacter infection in christchurch in the summer of 1992-93. N. Z. Med. J. 1994;107:430–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salihu M.D, Junaidu A.U, Magaji A.A, Rabiu Z.M. Study of Campylobacter in raw cow milk in Sokoto State, Nigeria. Br. J. Dairy Sci. 2010;1(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lastovica A.J, Allos M.B. Clinical significance of Campylobacter and related species other than Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. In: Nachamkin I, Szymanski C.M, Blaser M.J, editors. Campylobacter. 3rd Edn. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 2008. pp. 123–150. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for Antimicrobial Dilution and Disk Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or Fastidious Bacteria;Proposed Guideline. CLSI document M45-P. Wayne, Pennsylvania, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.External Quality Assurance System (EQAS) Protocol National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark (DTU Food), in Collaboration with Partners and Regional Sites in WHO GFN. 2013. [Accessed on 30.12.2013]. Available from: http://www.antimicrobialresistance.dk/data/images/eqas/who_2013-protocol-text.pdf .

- 31.Crushell E, Harty S, Sharif F, Bourke B. Enteric campylobacter: Purging its secrets? Pediatr. Res. 2004;55(1):3–12. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000099794.06260.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziprin R. L, Young C. R, Byrd J.A, Stanker L.H, Hume M.E, Gray S.A, Kim B. J, Kim M.E. Role of Campylobacter jejuni potential virulence genes in cecal colonization. Avian Dis. 2001;45:549–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziprin R. L, Young C.R, Stanker L.H, Hume M.E, Konkel M.E. The absence of cecal colonization of chicks by a mutant of Campylobacter jejuni not expressing bacterial fibronectin-binding protein. Avian Dis. 1999;43:586–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carvalho A.C, Ruiz-Palacios G.M, Ramos-Cervantes P, Cervantes L. E, Jian X, Pickering L. K. Molecular characterization of invasive and non-invasive Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001;39:1353–1359. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1353-1359.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poly F, Guerry P. Pathogenesis of Campylobacter. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2008;24(1):27–31. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282f1dcb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kazemeini H, Valizade Y, Parsaei P, Nozarpour N, Rahimi E. Prevalence of Campylobacter Species in Raw Bovine Milk in Isfahan, Iran. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2011;10(5):664–666. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wysok B, Wiszniewska A, Uradziński J, Szteyn J. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter in raw milk in the selected areas of Poland. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2011;14(3):473–477. doi: 10.2478/v10181-011-0070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rahimi E, Sepehri S, Momtaz H. Prevalence of Campylobacter species in milk and dairy products in Iran. Rev. Méd. Vét. 2013;164(5):283–288. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lovett J, Francis D.W, Hunt J.M. Isolation of Campylobacter jejuni from raw milk. Appl. Environm. Microbiol. 1983;46(2):459–462. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.2.459-462.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elango A, Dhamlakshmi B, Pugazhenthi T.R, Jayalalitha V, Kumar C.N, Doraisamy K.A. PCR- Restriction fragment length polymorphism of Campylobacter jejuni isolates. Egypt. J. Dairy Sci. 2009;37:169–173. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Italian Republic. Permanent Council State-Regions and Autonomous Provinces. AccordoStato - Regioni e Province Autonome 25-1-2007. Official Gazette No. 36 of 13rd of February 2007. Rome: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Singh H, Rathore R.S, Singh S, Cheema P. S. Comparative analysis of cultural isolation and PCR based assay for detection of Campylobacter jejuni in food and faecal samples. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2009;42(1):181–186. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822011000100022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wicker C, Giordano M, Rouger S, Sorin M. L, Arbault P. Campylobacter detection in food using an ELISA based method. Int J. Med. Microbiol. 2001;291(31):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jayarao B.M, Donaldson S.C, Straley B.A, Sawant A.A, Hegde N.V, Brown J. L. A survey of foodborne pathogens in bulk tank milk and raw milk consumption among farm families in Pennsylvania. J. Dairy Sci. 2006;89(7):2451–2458. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(06)72318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin T, Hulsey J, Basye D, Blush G, Anderson S, Neises D. Campylobacteriosis outbreak associated with unpasteurized milk- Reno county and Butler county. Kenvas Department of Health and Environment. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khanzadi S, Jamshidi A, Soltaninejad V, Khajenasiri S. Isolation and identification of Campylobacter jejuni from bulk tank milk in Mashhad- Iran. World Appl. Sci. J. 2010;9(6):638–643. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Giacometti F, Serraino A, Finazzi G, Daminelli P, Losio M.N, Arrigoni N, Piva S, Florio D, Riu R, Zanoni R. G. Sale of raw milk in Northern Italy: Safety implications and comparison of different analytical methodologies for detection of foodborne pathogens. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2012;9:293–297. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mabotel K.I, Mbewel M, Ateba C.N, Beighle D. Prevalence of Campylobacter contamination in fresh chicken, meat and milk obtained from markets in the North-West province, South Africa. J. Hum. Ecol. 2011;36(1):23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serraino A, Florio D, Giocometti F, Piva S, Mion D, Zanoni R.G. Presence of Campylobacter and Arcobacter species in in-line milk filters of farms authorized to produce and sell raw milk and of a water buffalo dairy farm in Italy. J. Dairy Sci. 2013;96(5):2801–2807. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-6249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giacometti F, Bonilauri P, Serraino A, Peli A, Amatiste S, Arrigoni N, Bianch M, Bilei S, Cascone G, Comin D, Daminelli P, Decastelli L, Fustini M, Mion R, Petruzzelli A, Rosmini R, Rugna G, Tamba M, Tonucci F, Bolzoni G. Four-Year monitoring of foodborne pathogens in raw milk sold by vending machines in Italy. J. Food Prot. 2013;11:1824–1993. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jain N, Shrivastava S. Study on bacteriological quality of marketed milk product (Indian Cheese) in Bhopal City, Madhya Pradesh, India. Sci. Secur. J. 2012;2:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vaishnavi C, Singh S, Grover R, Singh K. Bacteriological study of Indian cheese (paneer) sold in Chandigarh. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2001;19(4):224–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chatur Y.A, Brahmbhatt M.N, Modi S, Nayak J.B. Fluoroquinolone resistance and detection of topoisomerase gene mutation in Campylobacter jejuni. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014;3(6):773–783. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murphy G.J, Echeveria P, Jackson L, Arness M, Lebron C, Pitangrasi C. Ciprofloxacin - and azithromyan-resistant Campylobacter causing traveler's diarrhea in US troops deployed to Thailand on 1994. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1996;22(5):868–869. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.5.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bopp C.A, Birkness K.A, Wachsmuth I.K, Barrett T.J. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility, plasmid analysis, and serotyping of epidemic-associated Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1985;21:4–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.1.4-7.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wegmuller B, Lüthy J, Candrian U. Direct polymerase chain reaction detection of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in raw milk and dairy products. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993;59(7):2961–2965. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2161-2165.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fischer S.H, Nachamkin I. Common and variable domains of the flagellin gene, flaA, in Campylobacter jejuni. Mol. Microbiol. 1991;5(5):1151–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nuijten P.J, Asten F.J.V, Gaastra W, Van der Zeijst B.A. Structural and functional analysis of two Campylobacter jejuni. flagellin genes. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265(29):17798–17804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guerry P, Logan S.M, Thornton S, Trust T.J. Genomic organization and expression of Campylobacter flagellin genes. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172(4):1853–1860. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.1853-1860.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wassenaar T.M, Bleumink-Pluym N.M.C, Newell D.G, Nuijten P.J.M, Van Der Zeijst B.A.M. Differential flagellin expression in a flaAflaB +Mutant of Campylobacter jejuni. Infect. Immun. 1994;62(9):3901–3906. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3901-3906.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wassenaar T.M, Van Der Zeijst B.A.M, Ayling R, Newell D. G. Colonization of chicks by motility mutants of Campylobacter jejuni demonstrates the importance of flagellin A expression. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1993;139:1171–1175. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-6-1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wassenaar T.M. Molecular methods for detection, speciation and subtyping of Campylobacter spp. Lohmann inf. 2000;24:13–19. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Al-Amri A, Senok A.C, Ismaeel A.Y, Al-Mahmeed A.E, Botta G.A. Multiplex PCR for direct identification of Campylobacter spp. in human and chicken stools. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007;56(10):1350–1355. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47220-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cloak O.M, Fratamico P. M. A multiplex polymerase chain reaction for the differentiation of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli from a swine processing facility and characterization of isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and antibiotic resistance profiles. J. Food Protect. 2002;65(2):266–273. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-65.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nayak R, Stewart T.M, Nawaz M. S. PCR identification of Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter jejuni by partial sequencing of virulence genes. Mol. Cell Probes. 2005;19(3):187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Konkel M.E, Gray S.A, Kim B.J, Garvis S.G, Yoon J. Identification of the enteropathogens Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli based on the cad F virulence gene and its product. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999a;37(3):510–517. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.510-517.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Al-Mahmeed A, Senok A.C, Ismaeel A.V, Bindayna K.M, Tabbara K.S, Botta G.A. Clinical relevance of virulence genes in Campylobacter jejuni isolates in Bahrain. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006;55(7):839–843. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46500-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rizal A, Kumar A, Vidyarthi A.S. Prevalence of pathogenic genes in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from poultry and human. Internet J. Food Saf. 2010;12:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanad Y.M, Kassem I.I, Liu Z, Lin J, LeJeune J.T, Jeffrey T, Rajashekara G. Occurrence of the invasion associated marker (iam) in Campylobacter jejuni isolated from cattle. BMC Res. Notes. 2011;4:570. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wieczorek K, Osek J. Molecular characterization of Campylobacter spp. isolated from poultry faeces and carcasses in Poland. Acta Vet. Brno. 2010;80:019–027. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hendrixson D.R. A phase-variable mechanism controlling the Campylobacter jejuni FlgR response regulator influences commensalism. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61(6):1646–1659. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hendrixson D.R. Restoration of flagellar biosynthesis by varied mutational events in Campylobacter jejuni. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;70(2):519–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Karenlampi R, Rautelin H, Hanninen M.L. Evaluation of genetic markers and molecular typing methods for prediction of sources of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli infections. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73(5):1683–1685. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02338-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bang D.D, Nielsen E.M, Scheutz F, Pedersen K, Handberg K, Madsen M. PCR detection of seven virulence and toxin genes of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolates from Danish pigs and cattle and cytolethal distending toxin production of the isolates. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003;94(6):1003–1014. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Konkel M.E, Kim B.J, Rivera A.V, Garvis S.G. Bacterial secreted proteins are required for the internalization of Campylobacter jejuni into cultured mammalian cells. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32(4):691–701. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Acik M.N, Karahan M, Ongor H, Karagulle B, Cetinkaya B. Investigation of cytolethal distending toxin production and virulence genes in Campylobacter isolates from cattle. Rev. Méd. Vét. 2013;164(5):272–277. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khoshbakht R, Tabatabaei M, Shirzad A.H, Hosseinzadeh S. Occurrence of virulence genes and strain diversity of thermophilic campylobacters isolated from cattle and sheep faecal samples. Iran. J. Vet. Res., Shiraz Univ. 2014;15(2):138–144. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Linton D, Owen R.J, Stanley J. Rapid identification by PCR of the genus Campylobacter and of five Campylobacter species enteropathogenic for man and animals. Res. Microbiol. 1996;147(9):707–718. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(97)85118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Linton D, Lawson A.J, Owen R.J, Stanley J. PCR detection, identification to species level, and fingerprinting of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli direct from diarrheic samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997;35(10):2568–2572. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.10.2568-2572.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nachamkin I, Bohachick K, Patton C.M. Flagellin gene typing of Campylobacter jejuni by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993;31(6):1506–1531. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.6.1531-1536.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]