Abstract

Atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration has increased significantly and is projected to double by 2100. To increase current food production levels, understanding how pests and diseases respond to future climate driven by increasing CO2 is imperative. We investigated the effects of elevated CO2 (eCO2) on the interactions among wheat (cv. Yitpi), Barley yellow dwarf virus and an important pest and virus vector, the bird cherry-oat aphid (Rhopalosiphum padi), by examining aphid life history, feeding behavior and plant physiology and biochemistry. Our results showed for the first time that virus infection can mediate effects of eCO2 on plants and pathogen vectors. Changes in plant N concentration influenced aphid life history and behavior, and N concentration was affected by virus infection under eCO2. We observed a reduction in aphid population size and increased feeding damage on noninfected plants under eCO2 but no changes to population and feeding on virus-infected plants irrespective of CO2 treatment. We expect potentially lower future aphid populations on noninfected plants but no change or increased aphid populations on virus-infected plants therefore subsequent virus spread. Our findings underscore the complexity of interactions between plants, insects and viruses under future climate with implications for plant disease epidemiology and crop production.

Climate change is of global concern due to its predicted impacts on the environment and agriculture. Several atmospheric gases contribute to climate change including carbon dioxide (CO2). Since the beginning of the industrial revolution, the concentration of atmospheric CO2 has increased markedly and may more than double from its current level of about 400 μmol mol−1 to over 800 μmol mol−1 by the end of this century1. Numerous studies have addressed the different aspects of climate change in relation to plant physiology2. For example, elevated CO2 (eCO2) has positive effects on plant growth, expressed as higher yield, biomass, greater water-use efficiency, stimulation of higher rates of photosynthesis, changes to C:N ratios and improved light-use efficiency3,4,5.

Physiochemical changes to plants, mediated by eCO2 might have both direct and indirect effects on insect herbivores and on the epidemiology of pathogens transmitted by insects6,7. Studies that have investigated the influence of climate change on plant disease epidemiology indicate positive, negative or neutral effects8,9. Different climate factors including changes to temperature and CO2, drought, storm severity and rainfall, might affect the life cycle of plants, pathogens, and insect vectors and their dispersal as well as their interactions, and thus have the potential to alter the rate of infestation and pathogen spread10,11,12,13,14.

Changes to plant biochemistry occur when plants are exposed to higher CO2 levels, with a reduction of foliar nitrogen (N) concentration and a relative increase of carbon (C) (higher C:N ratios) due to the higher photosynthetic rates and growth3. Generally, many plant-chewing insects increase their feeding rates on plants grown under eCO2 to compensate for lower N levels in their host plant food source, but in many cases, the impact on insect growth and development is neutral or negligible and can be host plant specific15,16,17,18. Within the order Hemiptera, including aphids, there are reports suggesting an increase, decrease or no change to insect population levels when reared on plants subjected to eCO25,19,20,21. Aphids are among the most important agricultural pests worldwide and are major vectors of plant viruses; therefore, understanding the impact of eCO2 on aphid population dynamics and interactions with pathogens is essential in order to predict epidemiology of plant diseases under future climate6.

According to models, cereal aphid populations are likely to be larger with increased CO2 concentration if N levels are high, but if higher temperature and eCO2 are combined, aphid populations may remain at levels similar to current ones21,22. Research investigating the bird cherry-oat aphid (Rhopalosiphum padi) using open top chambers suggests larger population size and fecundity under increased CO2 concentration23. In another study, R. padi abundance increased with higher CO2 concentration when reared independently, but decreased in the presence of the grain aphid Sitobion avenae24. Studies on five plant-aphid combinations revealed species-specific responses with, for example, Myzus persicae increasing and Acyrthosiphon pisum decreasing in population size when exposed to eCO2, and concluded that phloem-feeders may not be negatively affected by higher CO2 levels20.

Rhopalosiphum padi is one of the most economically important insect pests of wheat (Triticum aestivum), and is the main vector of Barley yellow dwarf virus (BYDV) which causes a disease that can reduce cereal grain quality and yield by over 70%25. Aphids exclusively transmit this virus during feeding26,27 and feeding time and virus concentration can affect transmission efficiency28,29,30. To date, there is a paucity of research addressing aphid/plant/pathogen interactions under eCO2, and in particular, limited research has been done on the impacts of eCO2 on virus-infected plants. Malmstrom and Field31 reported that growth of BYDV-infected oats (Avena sativa) under eCO2 can lead to an increase in biomass, potentially allowing an increase in aphid population size and reservoir for the virus. Trębicki et al.13 documented an increase of over 36% of BYDV titer in wheat plants grown under eCO2 compared to aCO2, and Nancarrow et al.32 showed that increased temperature resulted in an earlier and higher peak of BYDV titer in wheat.

There is considerable evidence showing that vector-borne pathogens (including BYDV) can modify their hosts making them more suitable to the insect vector, thus promoting acquisition, transmission and spread of the virus30,33,34,35. Additionally, pathogen-induced changes in infected insect vectors alters their behavior which can facilitate pathogen spread36,37,38,39.

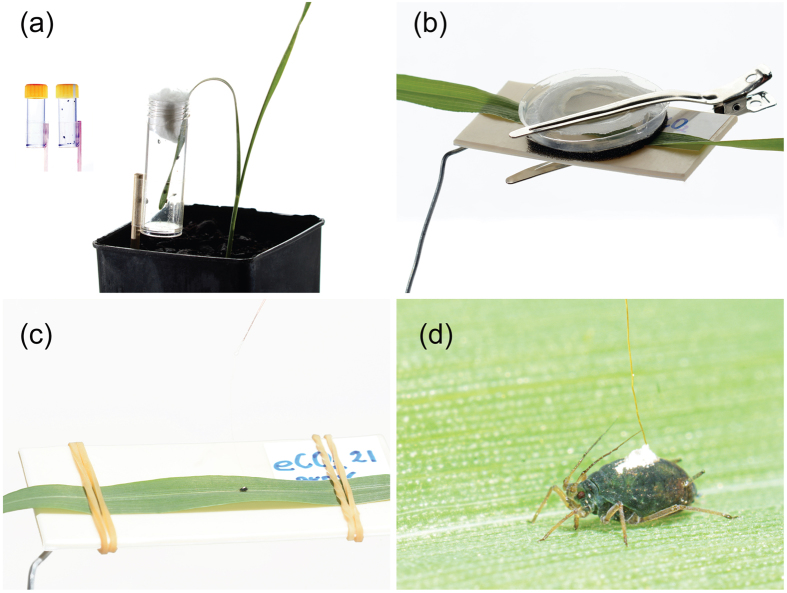

The main objective of this study was to investigate the interactions between R. padi, BYDV and wheat (cv. Yitpi) under a future climate, taking into consideration current ambient and predicted elevated CO2 levels (aCO2 = 385 μmol mol−1 and eCO2 = 650 μmol mol−1). The development, fecundity and feeding behavior of R. padi (Fig. 1) on BYDV-infected and noninfected plants were examined under both ambient and elevated CO2 using controlled environment chambers. The effects of aCO2 and eCO2 on plant growth and biochemistry were also examined.

Figure 1.

Illustration of (a) wheat inoculation with Barley yellow dwarf virus, where the tip of a leaf is inserted into a small tube containing 10 viruliferous adult R. padi and secured at the top with cotton wool to prevent aphid escape. All BYDV inoculations were performed using this method. (b) Clip cage used to study R. padi development and fecundity on noninfected and BYDV-infected plants under two CO2 levels. (c) During EPG, a leaf was placed on the support and secured with rubber bands to prevent plant movement. (d) Close up of R. padi probing on wheat, connected via silver glue and gold wire to the EPG insect electrode to record feeding behavior.

Results

R. padi development and fecundity

Two separate experiments were performed to study the development and fecundity of R. padi under ambient and eCO2. In the first experiment, we used noninfected plants, while BYDV-PAV-infected plants were used in the second experiment. R. padi development was unaffected by increased CO2 concentration on both noninfected and BYDV-infected wheat. The time between each instar, mean generation time and the period until R. padi reached maturity was similar for both CO2 treatments in each experiment (Table 1).

Table 1. R. padi performance on noninfected and BYDV-infected wheat under ambient (aCO2; 385 μmol mol−1) or elevated CO2 (eCO2; 650 μmol mol−1).

|

Noninfected plants |

BYDV-infected plants |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aCO2 | eCO2 | P value | aCO2 | eCO2 | P value | |

| d | 7.06 ± 0.17 | 7.05 ± 0.15 | 0.57 | 8.7 ± 0.25 | 8.7 ± 0.20 | 0.96 |

| Md | 45.9 ± 2.2 | 34.1 ± 4.5 | 0.0002 | 42.4 ± 3.6 | 42.6 ± 3.0 | 0.95 |

| M12 | 65.8 ± 3.4 | 43.7 ± 3.1 | 0.0002 | 49.6 ± 3.9 | 51.2 ± 3.7 | 0.76 |

| Td | 9.3 ± 0.22 | 9.5 ± 0.57 | 0.57 | 11.2 ± 0.7 | 11.8 ± 0.3 | 0.43 |

| rm | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.85 |

| RGR | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.85 |

d is the time (days) from birth to the onset of reproduction, Md is the reproductive output per aphid that represents the duration of d; M12 is the mean offspring number per female over the 12 day period; Td is the mean generation time; rm is the intrinsic rate of natural increase and RGR is the mean relative growth rate. ± sign indicates standard error of mean (SEM). N = 17.

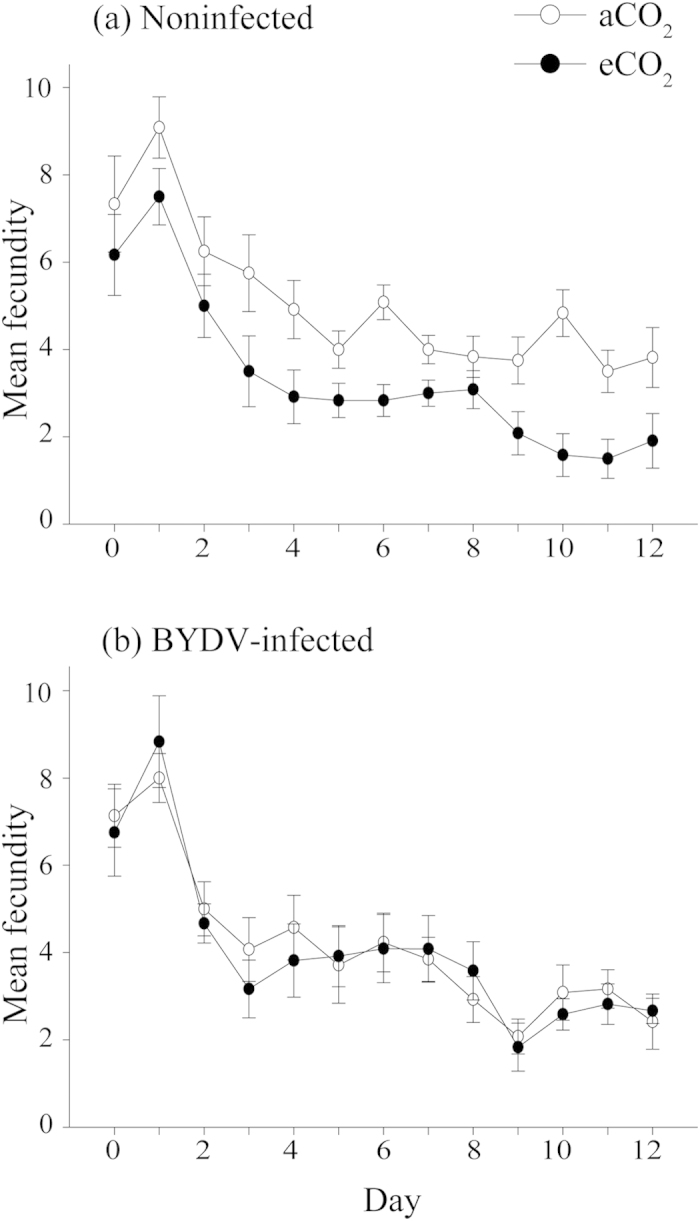

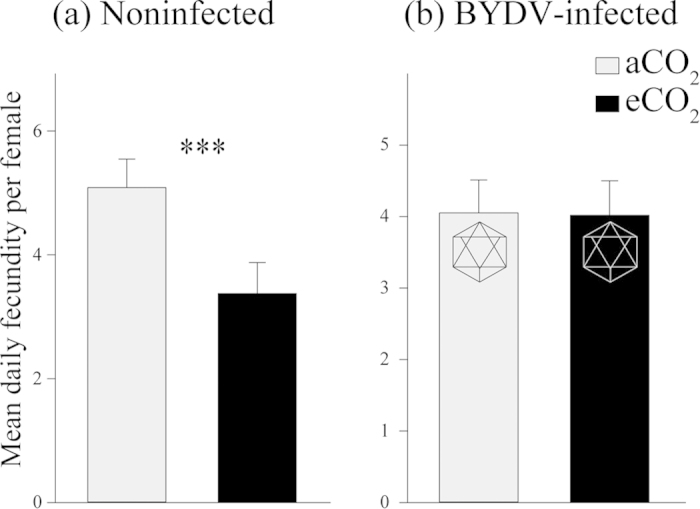

On noninfected plants, there was a significant negative effect of eCO2 on R. padi fecundity (Fig. 2a), which decreased by over 33% in average daily production of nymphs per adult compared to aCO2 (aCO2 = 5.08 and eCO2 = 3.37 nymphs, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3a). The average number of nymphs per adult within the time from birth to the onset of reproduction (Md) decreased by 26% under eCO2 and by 34% during the whole experimental period (M12) (Table 1). The intrinsic rate of natural increase (rm) and mean relative growth rate (RGR) also significantly decreased under eCO2 by around 10% (Table 1). Regardless of CO2 treatment, BYDV-infected wheat had no significant effect on aphid fecundity (Table 1, Figs 2b and 3b).

Figure 2.

R. padi fecundity on (a) noninfected and (b) BYDV-infected wheat plants grown under ambient (aCO2; 385 μmol mol−1) or elevated CO2 (eCO2; 650 μmol mol−1). Measured by the daily count of newly emerged nymphs, where day 0 indicates the point when aphids first reached maturity. Error bars represent standard error (SEM). N = 17.

Figure 3.

Mean daily fecundity per female recorded on wheat (a) noninfected and (b) BYDV-infected plants grown at ambient (385 μmol mol−1) or elevated (650 μmol mol−1) CO2 concentrations; * * * indicates significant difference at P < 0.001. Error bars represent standard error (SEM). Hexagon symbol indicates virus presence. N = 17.

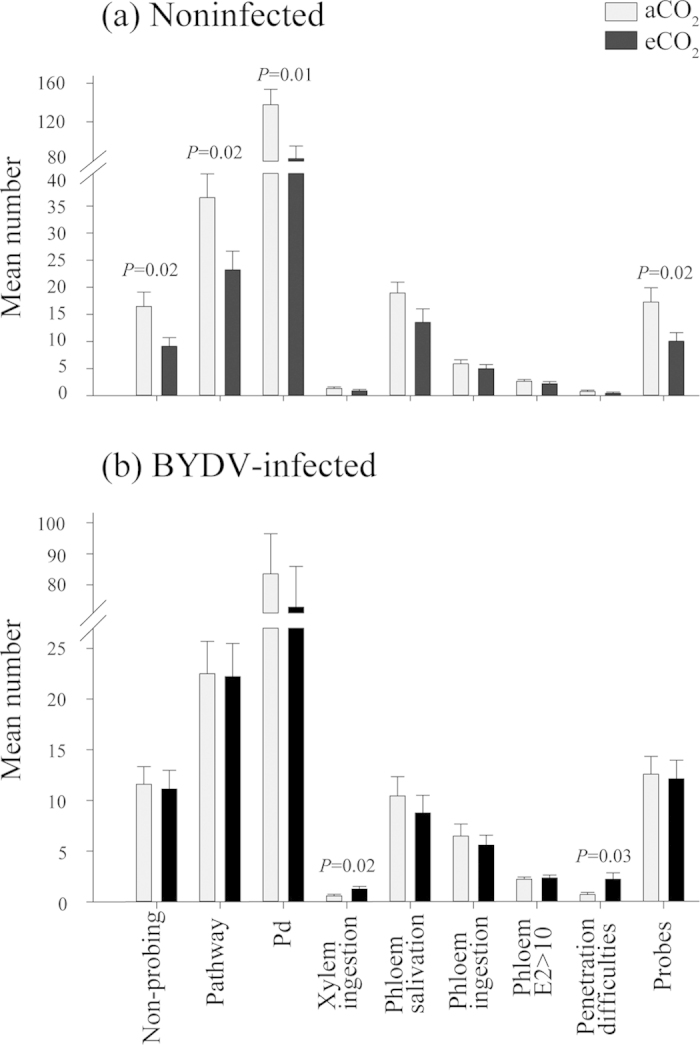

R. padi probing behavior

To study R. padi feeding behaviour, we implemented the electrical penetration graph (EPG) system, a tool commonly used to determine the plant penetration activities by sup-sacking insects. Several measured parameters of R. padi probing behavior, recorded using the EPG system, were significantly affected when aphids were exposed to plants grown under eCO2 levels. In the first feeding behavior experiment on noninfected plants, a number of non-probing events, pathways, potential drops (cell punctures) and probes (C phases) significantly decreased (P < 0.05) for aphids reared on eCO2-grown wheat plants compared to plants grown at aCO2 (Fig. 4a and Table S1). The mean number of pathways decreased significantly by 36% under eCO2, while other probing activities (as listed above and in Fig. 4a) decreased between 41–44% (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Number of R. padi probing activities on (a) noninfected plants and (b) BYDV-infected plants grown at ambient (385 μmol mol−1) or elevated (650 μmol mol−1) CO2 concentrations. Potential drop (Pd or intracellular penetration) indicates plant cell puncture, and Phloem E2 > 10 sustained phloem ingestion refers to phloem ingestion of ≥10 min. Where statistically significant, P values for each pair (aCO2, eCO2 treatments) are noted above the bars. Error bars represent standard error (SEM). Noninfected wheat N = 18, BYDV-infected wheat N = 22.

In the second feeding behavior experiment, BYDV-infected wheat plants were grown under aCO2 or eCO2 conditions and R. padi probing behavior was monitored. Parameters that were significantly higher in the noninfected plant experiment were, statistically non-significant on BYDV-infected plants regardless of CO2 levels(Fig. 4b and Table S2). However, xylem ingestion and penetration difficulties significantly increased on BYDV-infected plants grown under eCO2 (Fig. 4b, P < 0.05).

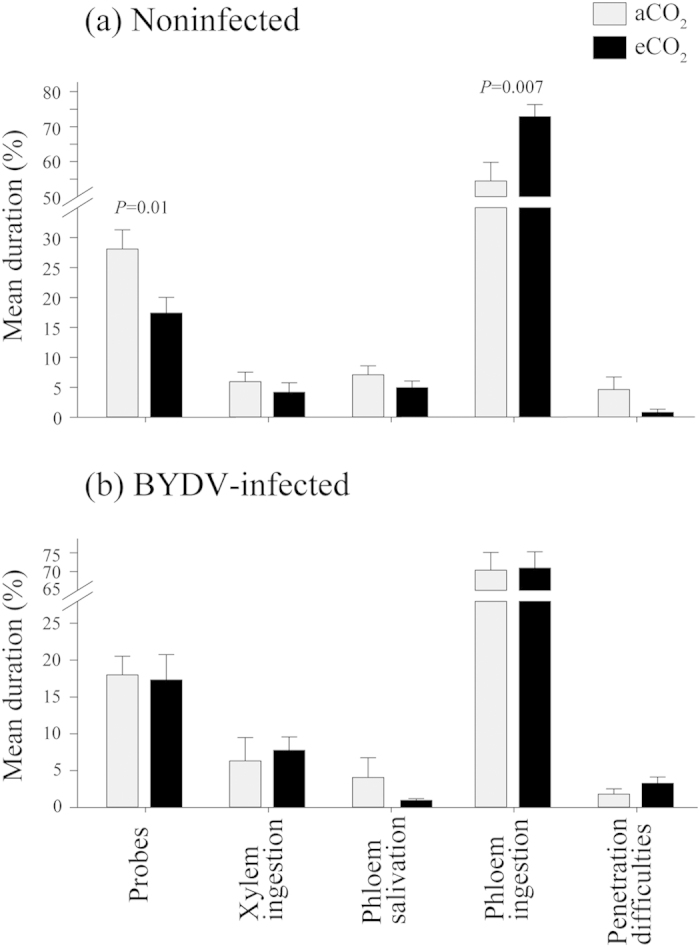

BYDV is a phloem-restricted virus, which requires aphid salivation into the phloem for transmission and phloem ingestion for acquisition. The duration of phloem ingestion (aphid feeding) on noninfected plants significantly increased by 34% (P = 0.007) under eCO2 compared to aCO2 conditions (Fig. 5a), but was unaffected on BYDV-infected plants (Fig. 5b). The mean duration (percentage of time) of R. padi probing activities devoted to phloem ingestion on eCO2-grown noninfected plants was 72%, compared to 54% on aCO2-grown plants. Additionally, on noninfected plants grown under eCO2, the duration of probes was significantly reduced by 38% (P = 0.01). No significant changes in the duration of xylem ingestion, phloem salivation or penetration difficulties were observed on noninfected plants grown under aCO2 and eCO2 (Fig. 5a). There was no significant difference between the time from first probe to phloem salivation between noninfected aCO2- and eCO2-grown wheat (aCO2 = 3433 s ± 364 SEM, eCO2 = 4516 s ± 596 SEM, P = 0.13) as well as other feeding parameters (Tables S1 and S2), suggesting a similar efficiency of BYDV transmission by aphids regardless of CO2 concentration. Similar to phloem ingestion, and in contrast to noninfected plants, other feeding behavior parameters were not significantly different in BYDV-infected plants grown under ambient and eCO2 (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Percentage duration (time) of R. padi probing activities on (a) noninfected and (b) BYDV-infected wheat plants grown at ambient (385 μmol mol−1) or elevated (650 μmol mol−1) CO2 concentrations. Where statistically significant, P values for each pair (aCO2, eCO2 treatments) are noted above the bars. Error bars represent standard error (SEM). Noninfected wheat N = 18, BYDV-infected wheat N = 22.

EPG analysis can also reveal plant suitability and resistance mechanisms, either physical or biochemical. EPG variables including the time from the beginning of the recording to the first phloem feeding activity (E), time from the first probe to the first phloem feeding activity and number of probes before the first phloem feeding activity, might indicate increased plant resistance and aphid difficulties locating the phloem. During both experiments on noninfected and BYDV-infected plants, none of these variables were significantly different with increased CO2 (Tables S1 and S2). Increased plant resistance at the phloem level can manifest by an increased period of aphid salivation (total or mean duration of E1) or a number of single phloem salivation periods (E1). Again, none of these variables were significantly different in either experiment (Tables S1 and S2).

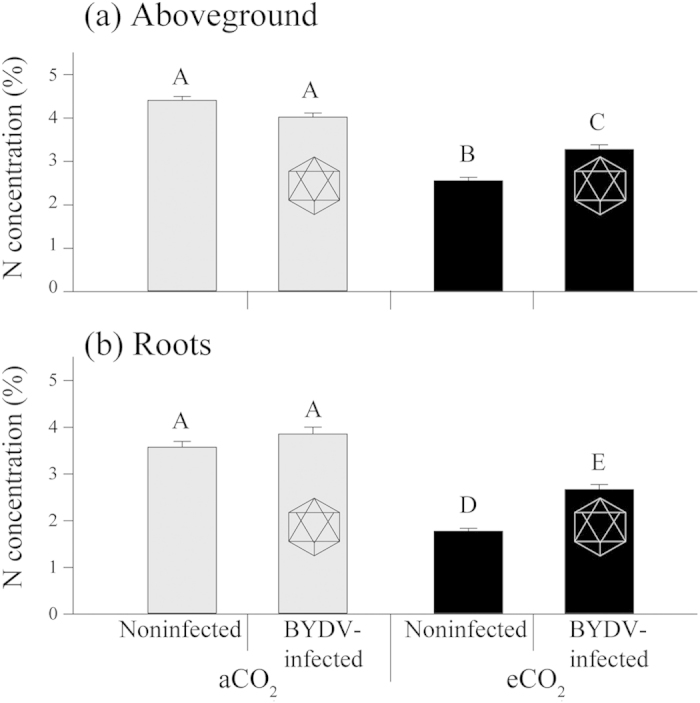

Plant N concentration

To determine changes in N concentration (%), analysis was done on noninfected and BYDV-infected plants that were equivalent in terms of growing conditions, virus status and collection time to plants utilized on both the aphid performance and feeding behavior experiments. Elevated CO2 had a significant negative effect on the concentration of N and C:N ratio in above-ground biomass (leaves and stems combined) and roots of both noninfected and BYDV-infected plants (Fig. 6a,b and Fig. S3a,b). Under eCO2, N concentration of noninfected plants decreased by 42% in aboveground tissue (Fig. 6a, P < 0.001) and by 50% in roots (P < 0.001, Fig. 6b). For BYDV-infected plants, a decrease in N concentration was also recorded from plants grown under eCO2 (aboveground P < 0.001, roots P < 0.001) but the decrease was less pronounced than in noninfected plants. BYDV-infected plants had a 19% (P < 0.001) and a 31% (P < 0.001) decrease in N in aboveground plant parts and roots, respectively, when grown under eCO2, compared to aCO2-grown BYDV-infected plants (Fig. 6a,b). Under aCO2, virus status (i.e., presence or absence) did not affect the % N in aboveground or roots. However, under eCO2 conditions BYDV infection significantly increased N concentration by 28% (P < 0.001) in aboveground tissue and by 50% (P < 0.001) in roots, compared to noninfected plants. Increased CO2 concentration had a positive effect on growth of both noninfected and BYDV-infected plants (Fig. S4).

Figure 6.

Nitrogen (N) concentration (%) of (a) aboveground plant parts and (b) roots of noninfected and BYDV-infected wheat plants grown under ambient (aCO2; 385 μmol mol−1) or elevated CO2 (eCO2; 650 μmol mol−1). Error bars represent standard error (SEM); different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between plant parts (aboveground and roots) and treatments (Tukey’s multiple range test, P < 0.05). Hexagon symbol indicates virus presence.

Discussion

This is the first report that demonstrates that plant virus infection can mediate the effects of elevated CO2 on plants and insect vectors of pathogens. BYDV-infected plants from the eCO2 treatment contained significantly less N aboveground than both noninfected and infected plants from the aCO2 treatment but had 28% more N than noninfected plants from the eCO2 treatment. The fact that BYDV infection increased the relative aboveground N plant concentration under eCO2 (Fig. 6) (reducing the gap in N content relative to noninfected and BYDV-infected plants grown under aCO2), and that no negative effect of BYDV infection was observed on aphid performance and phloem ingestion (Table 1, Figs 2, 3, 4, 5), indicate that a major factor influencing aphids under eCO2 is plant nitrogen content. This indicates that virus infection can mediate the effects of eCO2 on wheat (cv. Yitpi) and as a consequence can improve plant suitability for the vector.

A decrease in plant N concentration may negatively influence the performance of R. padi, as shown by reduced fecundity and increased phloem ingestion in eCO2-grown noninfected plants (Table 1, Figs 2, 3, 4, 5), as it may be linked to changes in concentration of amino acids (N-containing compounds) that are essential for aphid nutrition40. Amino acid concentrations (absolute and relative to specific carbohydrates such as sucrose) are commonly reduced under eCO2, which may in turn influence aphid performance24,41. The use of leaf N as a proxy for nutritional quality for phloem-feeding insects is not as ideal as using phloem sucrose:amino acid ratios, and therefore, a more detailed analysis of phloem biochemistry of wheat under eCO2 would be justified42. However, aphids are known to exhibit a strong response to host plants with different nitrogen levels. For example, two cereal aphids, R. padi and S. avenae reared on four wheat cultivars at different N regimes, increased in adult weight, fecundity and longevity with increased N treatments43. Cotton aphid (Aphis gossypii) abundance was also positively correlated with plant nitrogen content44. In our study, the intrinsic rate of increase of R. padi on noninfected plants was significantly reduced under eCO2 by around 10%, which potentially can be attributed to N reduction in those plants. In another study, R. padi’s intrinsic rate of increase also decreased on nitrogen deficient seedlings45.

Generally, herbivorous insects will be worse off under future predicted CO2 concentrations, as lower nutritional plant quality will have an impact on the development of immature stages and result in increased mortality16. Although many sap-sucking insects have been shown to respond differently in their population levels under eCO2, and the range of responses can be attributed to host specificity and feeding requirements, no single factor so far influencing the response to eCO2 has been identified15,16,17,18,19,20 and it is very likely that diverse factors will influence the interactions differently. In our study, R. padi development time was not affected by increased CO2 concentration, but reduced fecundity and increased feeding rates were recorded on noninfected plants. We also showed a 42% reduction in N content in aboveground tissue in noninfected plants under eCO2 (Fig. 6a). Using open top chambers and three CO2 levels, population size and fecundity of R. padi were shown to increase under eCO2 but not nymphal development23. In another open top chamber experiment using double the ambient CO2 concentration, R. padi increased in abundance, when reared independently, but decreased in the presence of S. avenae24. In a greenhouse experiment, R. padi abundance increased on barley under elevated CO2 concentration but development and fecundity remained unchanged; additionally no significant changes to phloem amino acids were recorded46. Using growth chambers and pepper plants grown under ambient or eCO2, Dader et al.5, recorded 37% reduction in fecundity and 11% longer pre-reproductive period of M. persicae under eCO2. Additionally, significantly lower N content was recorded in pepper plants under eCO2, which was attributed to the reduced fecundity and increased pre-reproductive period of M. persicae5. Potential differences between our and other experiments might be attributed to the growing conditions, CO2 levels, fertilizer application, plant cultivar and age, aphid genotype among other factors.

To our knowledge, no previous study has examined the effect of eCO2 on virus-infected plants in relation to nitrogen concentration, and also examined nitrogen concentration thresholds within the plant tissue and their effect on aphid performance. Although eCO2 reduced the N concentration of BYDV-infected plants, the N concentration gap between BYDV-infected plants was less than the N concentration gap between noninfected plants (Fig. 6). No differences were seen in R. padi performance and feeding on BYDV-infected plants between the ambient and eCO2 treatments and this can be attributed to increased N content under eCO2 due to the virus presence.

Concentration and composition of free amino acids or other components can influence insect performance as shown in artificial diets47. Alternatively, it could be argued that reduced performance of R. padi on eCO2-grown plants could be affected by associated changes to plant resistance or to plant structure, such as an increase in cell wall thickness, which could contribute to insect feeding difficulties, reflected by a decrease in probing activity. However, with increased CO2, while significant changes to cell wall thickness have been recorded in rice, such changes have not been observed in wheat48. Different EPG variables can provide mechanistic explanations of the interactions between aphid and the plant and can highlight host plant suitability or resistance mechanisms49. The duration of aphid probing and other activities before the insect can locate the phloem, which is its main feeding source, can indicate increased or reduced plant resistance, which can be attributed to plant morphological or structural changes. Our study showed that the time from the beginning of the recording to the first phloem feeding, the time from the first probe to the first phloem feeding, and number of probes before the first phloem feeding were not different in both experiments (noninfected and BYDV-infected plants) (Tables S1 and S2). Therefore, despite the CO2 levels, the similar effectiveness in locating the phloem indicates that if any changes to plant morphology and structure took place, they were not a barrier-affecting aphid probing. Additionally, after locating the phloem (sieve elements) and prior to ingestion, sap-sucking insects including aphids, inject saliva (E1 waveform) to overcome potential plant resistance factors at the phloem level. The duration and frequency of the saliva secretion can indicate host plant suitability and it can define hosts and non-host plants49. Hence, we measured these variables but no significant differences were observed among treatments (Tables S1 and S2). As result, there was no indication of increased plant resistance to R. padi feeding on wheat grown under eCO2 (Figs 4 and 5, Tables S1 and S2). This suggests that the observed changes in aphid performance and feeding behavior are not caused by structural changes of plants but are more likely linked to plant biochemistry and nutritional quality (Fig. 6, Fig. S1).

Under ambient CO2 conditions, it has been shown that vector-borne plant pathogens can modify host phenotype and vector behavior aiding disease spread by increasing nutritional quality or attractiveness of infected plants to their vectors33,36,38,50,51. This is true for many persistently transmitted viruses including BYDV, but is also specific to particular aphid species, plant (including cultivars) and virus combinations, and severity of virus infection. Under aCO2 levels, when reared on plants infected with BYDV, aphids had a significantly shorter developmental time and/or increased fecundity compared to noninfected plants35,50,52. This may be caused by the increase in total amino acid content of plant tissue associated with BYDV infection53, but no conclusive studies have demonstrated this to be the case. We did not observe a shorter developmental period and increased fecundity of R. padi in BYDV-infected plants under aCO2 (Figs 2b and 3b). Differences between our findings and previous studies might be related to the experimental protocol or wheat variety utilized for the studies among other factors. In our study, C:N ratio decreased (Fig. S3) and N concentration increased (Fig. 6) in the eCO2-grown BYDV-infected plants, which might be associated with an increased level of amino acids, but additional studies would be required to assess this. Apart from the suggested alteration of nutritional quality of wheat, BYDV infection modifies the relative concentration of volatile organic compounds emitted by the plant, eliciting an aphid response, and increasing attractiveness and settling of nonviruliferous aphids51,54. Changes to R. padi behavior are also attributed to the presence or absence of BYDV within the vector. The ‘Vector Manipulation Hypothesis’ (VMH) by Ingwell et al.36, proposes that attraction of R. padi to either BYDV infected or noninfected wheat plants depends on whether the vector is carrying the virus, adding another layer to the already complex relationship between R. padi, wheat and BYDV, which can be further influenced by eCO2 or increased temperature. This complex interaction, which is often host, vector and virus-specific, has important implications for epidemiology and disease spread. Behavioral studies of virus-infected insects as influenced by CO2 levels are merited to determine if and how vector manipulation occurs under eCO2. Additionally, the effects of eCO2 on plant volatile organic compound profiles need to be assessed to understand the full impact of future climate on vector behavior.

As no evidence of increased plant resistance under eCO2 could be identified in this study, we predict that an eCO2 environment will not delay or reduce virus spread (Figs 4 and 5, Table S1 and S2). Additionally, under eCO2, no decrease in development and fecundity of R. padi on BYDV-infected plants was recorded, hence it is likely that eCO2 will not reduce the current levels of viruliferous aphids and virus spread. Moreover, increases in BYDV titer in wheat with increased temperature32 and CO213 might intensify disease spread by increasing virus transmission and acquisition efficiency. Using oats and the BYDV pathosystem under aCO2 and eCO2, Malmstrom and Field31 concluded that increased persistence of BYDV-infected plants under eCO2 may alter disease epidemiology. Since the response of aphids to plants is species-specific and can be influenced differently by eCO2, the significance of non-crop hosts is also important if we are to understand aphid population dynamics and the initial introduction of the viruses into a crop.

Although other studies have investigated the effect of eCO2 on noninfected plant physiology and biochemistry to identify potential yield impacts, studies of interactions between eCO2 and virus-infected plants are scarce. Thus, understanding of these interactions and accurate predictions of virus epidemiology are required, and only then can we predict more realistic impacts on crop physiology and yield. In this first study, we move a step further, by including insect interactions, which are a vital component of virus epidemiology. Using noninfected, BYDV-infected wheat and coupling aphid performance with feeding behaviour studies (EPG) and plant biochemistry, provides mechanistic explanations of the interactions and their complexity. Further research is needed to understand the impact of a changing climate on the yield and quality of wheat cultivars overlayed by pests and diseases, which are important factors in agricultural production.

Methods

Insect and plant material

All R. padi used in this study were derived from a single parthenogenetic female obtained from vegetation located at the Grains Innovation Park (GIP) facility in Horsham, Australia. The clonal lineage was reared, in a constant-temperature growth chamber at 20 °C 14:10 D:L, for over 15 generations on wheat (cv. Yitpi) prior to the experiment. Five-week old wheat plants (cv. Yitpi) were used in all experiments. Plants were grown in 0.68 L plastic pots filled with potting mix containing slow release fertilizer, additional trace elements of iron and lime in temperature and CO2-controlled plant growth cabinets at 20 °C, and 14:10 D:L photoperiod (light intensity ca. 1000 μmol m−2 s−1 at the top of the plant canopy, generated within each chamber by five 400 W high-pressure sodium and four 70 W incandescent globes) (Thermoline Scientific, TPG-1260). Potted plants were placed in trays and basal watered to maintain a standardised watering regime across all treatments. Growth cabinets were set at one of two CO2 levels (ambient: aCO2 = 385 μmol mol−1; or elevated: eCO2 = 650 μmol mol−1). On a weekly basis, CO2 concentrations and plants were alternated between the chambers to minimise any potential chamber effect.

Virus source and inoculation

Barley yellow dwarf virus, PAV (BYDV-PAV) was used for all experiments to inoculate wheat plants in the virus positive treatment group. The PAV serotype was originally collected in Horsham, Australia from A. sativa plants located near the GIP Horsham premises. The virus was confirmed by PCR using PAV-specific primers and Tissue Blot Immunoassay (TBIA) methods13. To rule out multiple infection, PCR and TBIA tests for other species of BYDV or Cereal yellow dwarf virus (CYDV) were performed and found to be negative. BYDV-PAV was maintained at the DEPI facility on wheat (cv. Yitpi) in plant growth chambers (20 °C; 14D:10L). Subsequently, all experimental plants were also tested to confirm presence or absence of the virus using the TBIA method. Across all experiments, virus inoculation was standardised, using the same age source plants and aphid vectors. Eight to ten days after sowing, at the two-leaf stage, plants were inoculated with virus by exposure to 10 viruliferous aphids per plant. The tip of the leaf (approximately 4 cm long) of each plant was inserted into a small clear plastic tube containing the infected aphids and sealed with cotton wool (Fig. 1a). After 72 hours, all aphids were carefully removed.

R. padi development and fecundity

To understand the effect of elevated CO2 on R. padi performance, two experiments were designed. In the first, we monitored the nymphal development and fecundity of R. padi on noninfected wheat plants grown under two CO2 conditions. In the second experiment, we used BYDV-infected plants, but otherwise all of the experimental conditions remained the same as in the first experiment. Both experiments were conducted in growth chambers, using the variety and growth conditions described above. A single young adult female was placed on the 3rd leaf of the main stem and housed in an individual clip cage (Fig. 1b). After four hours, the adult aphid was removed and all but one newly emerged nymph was left. To measure development, 17 insect replicates were assessed every 24 hours until adulthood. During each assessment, instar number were recorded and shed exuvia were removed. Once aphids reached adulthood, fecundity was monitored on 17 biological replicates (one plant and one insect each) by counting and removing nymphs every 24 hours for 12 days.

R. padi feeding behavior

To understand the effect of elevated CO2 on aphid feeding behavior the electrical penetration graph (EPG)55,56 method was used. EPG is a commonly used method to study feeding behavior on many sap-sucking insects38,49,57,58. R. padi (1–4 day-old adults) was monitored first on noninfected wheat plants grown under elevated or ambient CO2 conditions (18 biological replicates, 16 h duration of each recording). Then feeding behavior was assessed on BYDV-infected plants grown under elevated or ambient CO2 conditions (22 biological replicates, 14 h duration of each recording). All experimental conditions remained the same across both experiments. EPG recordings were performed using the same settings, with plant voltage adjusted for each channel to ensure the first insect probe was always positive with a maximum amplitude of around +4 V. For each recording, the quality of silver glue connection between aphid and insect electrode was tested by using a calibration pulse after the first probe was initiated, and a good contact was determined by an output signal in the form of a square pulse. Probing by R. padi was monitored using an EPG Giga-8 amplifier (EPG-Systems, Wageningen, The Netherlands). All recordings were conducted within a Faraday cage housed inside a climate-controlled laboratory room (22 + 3 °C). EPG output was set to 50x gain and data was acquired at 100 Hz using a DATAQ Di710 A/D data acquisition USB device card (Dataq® instruments, Ohio, USA). EPG waveforms, which represent specific probing activity, were (Figs S1 and S2) analysed using Stylet+a software (EPG systems, Wageningen, The Netherlands). Since aphids are active when disturbed, each insect was transferred onto a vacuum device platform for tethering. Insects were attached to the electrode using a small droplet of water-based silver glue (EPG-Systems, Wageningen, The Netherlands) placed on the abdomen using a fine entomological pin (Fig. 1c,d). After 20 s, a second droplet of silver glue was added and a gold wire (12.5 μm diameter, 2 cm length) was placed in the glue and allowed to dry. The gold wire was attached by silver glue to a 0.2 mm diameter copper wire attached to a brass pin that was inserted into the input connector of the first-stage amplifier. Each wired aphid was left tethered for 1 h and then placed in the centre of the probing substrate.

N analysis of plant tissue

To quantify potential effects of eCO2 on plant growth and biochemistry and the subsequent impacts on aphid performance and feeding behavior, another set of noninfected and BYDV-infected plants were grown at elevated or ambient CO2 conditions and analysed for total carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) concentration (%). Virus inoculation, growing medium, temperature and CO2 concentration were identical as for both previous experiments. Ten biological replicates each of five–week-old plants were harvested and the above-ground biomass (leaves and stems) and roots were dried at 65 °C for 48 h then finely ground (<0.5 mm) using a ball mill (Retsch MM 300). The percent of N and C concentration of aboveground biomass and roots was determined by the Dumas combustion method using a CHN analyser (CHN 2000; LECO, St Joseph, MI, USA) at the University of Melbourne, Creswick. The C:N ratio was calculated by dividing % C by % N for each plant tissue.

Data analysis

To assess R. padi performance the intrinsic rate of natural increase (rm) was calculated59, using the equation rm = 0.748* (ln Md)/d, where 0.748 is a correction factor, d is the time from birth to the onset of reproduction and the Md is the reproductive output per aphid that represents the duration of d that was used. Additionally, we calculated mean relative growth rate (RGR = rm/0.86), mean generation time (Td = d/0.738) and mean offspring number per female over the 12-day period (M12). Statistical analysis was performed on each individual insect EPG recording as well as on combined recordings for each treatment. Online resources were used to calculate EPG parameters (Tables S1 and S2)60. For aphids performance and feeding behaviour experiments, summary statistics and t-tests were performed using Microsoft excel and R statistical software, analysis of variance and Tukey’s HSD for multiple comparisons test was done using R statistical software for C and N between the treatments.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Trębicki, P. et al. Virus infection mediates the effects of elevated CO2 on plants and vectors. Sci. Rep. 6, 22785; doi: 10.1038/srep22785 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Agriculture Victoria, Department of Economic Development, Bioscience Research and the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC), Australia. We thank Audrey Delahunty, Simone Dalton, Narelle Nancarrow and Mohammad Aftab for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Author Contributions P.T., J.E.L., N.B.-P. and A.J.F. designed the experiments; P.T. and R.V. conducted the experiments; P.T. and R.V. analysed the results; P.T., R.K.V., N.B.-P., K.S.P., B.D., A.J.F., A.L.Y., G.J.F., J.E.L. wrote the main manuscript text; P.T. prepared figures and took the photographs; all authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth E. A. & Long S. P. What have we learned from 15 years of free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE)? A meta-analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy properties and plant production to rising CO2. New Phytol. 165, 351–372, doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01224.x (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball B. A., Kobayashi K. & Bindi M. In Advances in Agronomy Vol. 77 (ed Donald L. Sparks) 293–368 (Academic Press, 2002).

- Drake B. G., Gonzàlez-Meler M. A. & Long S. P. More efficient plants: a consequence of rising atmospheric CO2? Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 48, 609–639 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dáder B., Fereres A., Moreno A. & Trębicki P. Elevated CO2 impacts bell pepper growth with consequences to Myzus persicae life history, feeding behaviour and virus transmission ability. Sci. Rep. 6, 19120; doi: 10.1038/srep19120 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canto T., Aranda M. A. & Fereres A. Climate change effects on physiology and population processes of hosts and vectors that influence the spread of hemipteran-borne plant viruses. Glob. Chang. Biol . 15, 1884–1894 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Garrett K., Dendy S., Frank E., Rouse M. & Travers S. Climate change effects on plant disease: genomes to ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44, 489–509 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coakley S. M., Scherm H. & Chakraborty S. Climate change and plant disease management. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 37, 399–426 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck J. et al. Climate change and diseases of food crops. Plant Pathol. 60, 113–121, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02414.x (2011). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P. K. et al. Emerging infectious diseases of plants: pathogen pollution, climate change and agrotechnology drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 535–544, doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.07.021 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S., Tiedemann A. & Teng P. Climate change: potential impact on plant diseases. Environ. Pollut. 108, 317–326 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig C., Iglesias A., Yang X., Epstein P. R. & Chivian E. Climate change and extreme weather events; implications for food production, plant diseases, and pests. Global Change & Human Health 2, 90–104 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Trębicki P. et al. Virus disease in wheat predicted to increase with a changing climate. Glob. Chang. Biol. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12941 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T. S., Bosque-Pérez N. A., Foote N. E., Magney T. & Eigenbrode S. D. Environmentally dependent host–pathogen and vector–pathogen interactions in the Barley yellow dwarf virus pathosystem. J. Appl. Ecol. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12484 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bezemer T. M. & Jones T. H. Plant-insect herbivore interactions in elevated atmospheric CO2: quantitative analyses and guild effects. Oikos 82, 212–222 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Coviella C. E. & Trumble J. T. Effects of elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide on insect-plant interactions. Conserv. Biol. 13, 700–712 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Traw M., Lindroth R. & Bazzaz F. Decline in gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) performance in an elevated CO2 atmosphere depends upon host plant species. Oecologia 108, 113–120 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson E. A., Ryan G. D. & Newman J. A. A meta-analytical review of the effects of elevated CO2 on plant–arthropod interactions highlights the importance of interacting environmental and biological variables. New Phytol. 194, 321–336, doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04074.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn D. F., Sudderth E. A. & Bazzaz F. Effects of aphid herbivory on biomass and leaf-level physiology of Solanum dulcamara under elevated temperature and CO2. Environ. Exp. Bot. 56, 10–18 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Hughes L. & Bazzaz F. A. Effects of elevated CO2 on five plant-aphid interactions. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 99, 87–96 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Newman J. A. Climate change and cereal aphids: the relative effects of increasing CO2 and temperature on aphid population dynamics. Glob. Chang. Biol . 10, 5–15 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Newman J. A. Climate change and the fate of cereal aphids in Southern Britain. Glob. Chang. Biol . 11, 940–944, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.00946.x (2005). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xing G. et al. Impacts of atmospheric CO2 concentrations and soil water on the population dynamics, fecundity and development of the bird cherry-oat aphid Rhopalosiphum padi. Phytoparasitica 31, 499–514 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. C., Chen F. J. & Ge F. Elevated CO2 changes interspecific competition among three species of wheat aphids: Sitobion avenae, Rhopalosiphum padi, and Schizaphis graminum. Environ. Entomol. 38, 26–34 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. R. & Sward R. J. Crop loss assessment studies on the effects of Barley yellow dwarf virus in wheat in Victoria. Aust. J. Agric. Res . 33, 179–185 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. M. & Gildow F. E. Luteovirus-aphid interactions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 41, 539–566 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M. E. & Thresh J. M. Epidemiology of barley yellow dwarf: A Study in ecological complexity. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 28, 393–424, doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.28.090190.002141 (1990). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. M., Power A. G., Smith D. M., Seaman A. J. & Altman N. S. Aphid transmission of Barley yellow dwarf virus: Acquisition access periods and virus concentration requirements. Phytopathology 81, 539–545 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. M., Smith D. & Sorrells M. Reduction of disease incidence in small field plots by isolate-specific resistance to Barley yellow dwarf virus. Phytopathology 84, 713–718 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Martínez E. S. & Bosque-Pérez N. A. Variation in Barley yellow dwarf virus transmission efficiency by Rhopalosiphum padi (Homoptera: Aphididae) after acquisition from transgenic and nontransformed wheat genotypes. J. Econ. Entomol. 97, 1790–1796, doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-97.6.1790 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmstrom C. M. & Field C. B. Virus-induced differences in the response of oat plants to elevated carbon dioxide. Plant Cell Environ. 20, 178–188, doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1997.d01-63.x (1997). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nancarrow N. et al. The effect of elevated temperature on Barley yellow dwarf virus-PAV in wheat. Virus Res. 186, 97–103, doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.12.023 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereres A. & Moreno A. Behavioural aspects influencing plant virus transmission by homopteran insects. Virus Res. 141, 158–168 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauck K. E., De Moraes C. M. & Mescher M. C. Deceptive chemical signals induced by a plant virus attract insect vectors to inferior hosts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci . 107, 3600–3605, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907191107 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereres A., Lister R., Araya J. & Foster J. Development and reproduction of the English grain aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae) on wheat cultivars infected with Barley yellow dwarf virus. Environ. Entomol. 18, 388–393 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- Ingwell L. L., Eigenbrode S. D. & Bosque-Pérez N. A. Plant viruses alter insect behavior to enhance their spread. Sci. Rep . 2, 1–6, doi: 10.1038/srep00578 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini X., Hoffmann M., Coy M. R., Stelinski L. L. & Pelz-Stelinski K. S. Infection of an insect vector with a bacterial plant pathogen increases its propensity for dispersal. PLoS ONE 10, e0129373, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129373 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford C. A., Walker G. P. & Ullman D. E. Infection with a plant virus modifies vector feeding behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 9350–9355, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100773108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casteel C. L. et al. The NIa-Pro protein of Turnip mosaic virus improves growth and reproduction of the aphid vector, Myzus persicae (green peach aphid). Plant J. 77, 653–663 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas A. Phloem-sap feeding by animals: problems and solutions. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 747–754 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Högy P. et al. Effects of elevated CO2 on grain yield and quality of wheat: results from a 3-year free-air CO2 enrichment experiment. Plant Biol. 11, 60–69 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karley A. J., Douglas A. E. & Parker W. E. Amino acid composition and nutritional quality of potato leaf phloem sap for aphids. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 3009–3018 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aqueel M. & Leather, S. Effect of nitrogen fertilizer on the growth and survival of Rhopalosiphum padi (L.) and Sitobion avenae (F.)(Homoptera: Aphididae) on different wheat cultivars. Crop Prot. 30, 216–221 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Cisneros J. J. & Godfrey L. D. Midseason pest status of the cotton aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae) in California cotton - is nitrogen a key factor? Environ. Entomol. 30, 501–510, doi: 10.1603/0046-225x-30.3.501 (2001). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ponder K., Pritchard J., Harrington R. & Bale J. Difficulties in location and acceptance of phloem sap combined with reduced concentration of phloem amino acids explain lowered performance of the aphid Rhopalosiphum padi on nitrogen deficient barley (Hordeum vulgare) seedlings. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 97, 203–210 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Ryan G. D., Sylvester E. V., Shelp B. J. & Newman J. A. Towards an understanding of how phloem amino acid composition shapes elevated CO2-induced changes in aphid population dynamics. Ecol. Entomol. 40, 247–257 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Trębicki P., Harding R. M. & Powell K. S. Anti-metabolic effects of Galanthus nivalis agglutinin and wheat germ agglutinin on nymphal stages of the common brown leafhopper using a novel artificial diet system. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 131, 99–105 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C. et al. The temporal and species dynamics of photosynthetic acclimation in flag leaves of rice (Oryza sativa) and wheat (Triticum aestivum) under elevated carbon dioxide. Physiol. Plant. 145, 395–405, doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01581.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trębicki P., Tjallingii W. F., Harding R. M., Rodoni B. C. & Powell K. S. EPG monitoring of the probing behaviour of the common brown leafhopper Orosius orientalis on artificial diet and selected host plants. Arthropod Plant Interact . 6, 405–415 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Bosque-Pérez N. A. & Eigenbrode S. D. The influence of virus-induced changes in plants on aphid vectors: Insights from luteovirus pathosystems. Virus Res. 159, 201–205 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Martínez E. S. et al. Volatile cues influence the response of Rhopalosiphum padi (Homoptera: Aphididae) to Barley yellow dwarf virus-infected transgenic and untransformed wheat. Environ. Entomol. 33, 1207–1216 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Martínez E. S., Bosque-Pérez N. A., Berger P. H. & Zemetra R. S. Life history of the bird cherry-oat aphid, Rhopalosiphum padi (Homoptera: Aphididae), on transgenic and untransformed wheat challenged with Barley yellow dwarf virus. J. Econ. Entomol. 97, 203–212 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi O. The effect of Barley yellow dwarf virus on the amino acid composition of spring wheat. Ann. Appl. Biol. 108, 145–149 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Ortega K. J., Bosque-Pérez N. A., Ngumbi E., Jiménez-Martínez E. S. & Eigenbrode S. D. Rhopalosiphum padi (Hemiptera: Aphididae) responses to volatile cues from Barley yellow dwarf virus-infected wheat. Environ. Entomol. 38, 836–845 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjallingii W. F. In Aphids, Their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control (eds Minks A. K. & Harrewijn P.) 95–108 (Elsevier, 1988). [Google Scholar]

- Tjallingii W. Electronic recording of penetration behaviour by aphids. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 24, 721–730 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Backus E. A., Holmes W. J., Schreiber F., Reardon B. J. & Walker G. P. Sharpshooter X wave: correlation of an electrical penetration graph waveform with xylem penetration supports a hypothesized mechanism for Xylella fastidiosa inoculation. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 102, 847–867 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Walker G. P. In Principles and applications of electronic monitoring and other techniques in the study of Homopteran feeding behavior (eds Walker G. P. & Backus E. A.) 14–40 (Entomological Society of America, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt I. & White P. Simple estimation of intrinsic increase rates for aphids and tetranychid mites. J. Appl. Ecol. 757–766 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Sarria E., Cid M., Garzo E. & Fereres A. Excel workbook for automatic parameter calculation of EPG data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 67, 35–42 (2009). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.