Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cryptococcal meningitis associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection causes more than 600,000 deaths each year worldwide. Treatment has changed little in 20 years, and there are no imminent new anticryptococcal agents. The use of adjuvant glucocorticoids reduces mortality among patients with other forms of meningitis in some populations, but their use is untested in patients with cryptococcal meningitis.

METHODS

In this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, we recruited adult patients with HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis in Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, Laos, Uganda, and Malawi. All the patients received either dexamethasone or placebo for 6 weeks, along with combination antifungal therapy with amphotericin B and fluconazole.

RESULTS

The trial was stopped for safety reasons after the enrollment of 451 patients. Mortality was 47% in the dexamethasone group and 41% in the placebo group by 10 weeks (hazard ratio in the dexamethasone group, 1.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.84 to 1.47; P = 0.45) and 57% and 49%, respectively, by 6 months (hazard ratio, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.91 to 1.53; P = 0.20). The percentage of patients with disability at 10 weeks was higher in the dexamethasone group than in the placebo group, with 13% versus 25% having a prespecified good outcome (odds ratio, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.69; P<0.001). Clinical adverse events were more common in the dexamethasone group than in the placebo group (667 vs. 494 events, P = 0.01), with more patients in the dexamethasone group having grade 3 or 4 infection (48 vs. 25 patients, P = 0.003), renal events (22 vs. 7, P = 0.004), and cardiac events (8 vs. 0, P = 0.004). Fungal clearance in cerebrospinal fluid was slower in the dexamethasone group. Results were consistent across Asian and African sites.

CONCLUSIONS

Dexamethasone did not reduce mortality among patients with HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis and was associated with more adverse events and disability than was placebo. (Funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development and others through the Joint Global Health Trials program; Current Controlled Trials number, ISRCTN59144167.)

Cryptococcal meningitis associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is estimated to cause more than 600,000 deaths each year, the vast majority in sub-Saharan Africa and in South and Southeast Asia.1 Among patients receiving combination antifungal therapy with amphotericin B and either flucytosine or fluconazole, mortality remains more than 30% at 10 weeks, and survivors often have substantial disability.2,3 There is a pressing need to improve outcomes. However, no new anticryptococcal agents are currently close to approval for clinical use, so innovative strategies are needed.

Adjunctive treatments, such as glucocorticoids, have shown some benefit in central nervous system (CNS) infections in certain settings. For example, dexamethasone reduced mortality from acute bacterial meningitis among adults in Europe and those with microbiologically confirmed disease in Vietnam.4,5 Dexamethasone reduced mortality in a mixed cohort of HIV-infected and uninfected adults with tuberculous meningitis in Vietnam, but the study was not powered to show an effect in the subgroup of patients with HIV infection.6 Cryptococcal meningitis shares pathophysiological features with tuberculous meningitis, including vasculitis, cerebral edema, and raised intracranial pressure,7 all of which may be modified by glucocorticoids.

Glucocorticoids are inexpensive and readily available in regions in which the burden of cryptococcal meningitis is highest; low rates of adverse events have been observed among patients with CNS infections.5,6,8 Retrospective data suggest that glucocorticoids may reduce the risk of blindness in HIV-uninfected patients with cryptococcal meningitis,9 and studies in animals suggest that the use of such drugs does not reduce the sterilizing power of amphotericin or fluconazole and improves survival even in the absence of antifungal therapy.10,11 Glucocorticoids are widely used in clinical practice for cryptococcal meningitis in high-burden settings, particularly in Asia, and international guidelines recommend their use in some circumstances.12 However, data from controlled trials are lacking. We conducted a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to determine whether adjunctive treatment with dexamethasone would improve survival among adults with HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis.13

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

The full details regarding the enrollment procedures have been described previously13 and are provided in the study protocol (available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org), with study-site information provided in Section 1 in the Supplementary Appendix, also available at NEJM.org. In brief, we recruited adult patients (≥18 years of age) in 13 hospitals in Indonesia, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, Malawi, and Uganda. Eligible patients had HIV infection, a clinical syndrome consistent with cryptococcal meningitis, and microbiologic confirmation of disease, as indicated by one or more of the following test results: positive India ink staining of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), culture of cryptococcus species from CSF or blood, or cryptococcal antigen detected in CSF on cryptococcal antigen lateral flow assay (IMMY). We excluded patients who were pregnant, had renal failure, had gastrointestinal bleeding, had received more than 7 days of anticryptococcal antifungal therapy, were already taking glucocorticoids, or required glucocorticoid therapy for coexisting conditions. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients or their representatives.

RANDOMIZATION, TREATMENT CONCEALMENT, AND BLINDING

Randomization in a 1:1 ratio was performed with variable block sizes of 4 and 6, with stratification according to site. The computer-generated randomization list was accessible only to the central study pharmacists in Vietnam, who used it to prepare blinded, sealed treatment packs containing dexamethasone or identical placebo, which were distributed to the sites. We used site-specific enrollment logs to assign patients to the next available sequential patient number and corresponding treatment pack.

LABORATORY INVESTIGATIONS

Lumbar punctures were performed on study days 1, 3, 7, and 14 and more frequently if clinically indicated; quantitative fungal counts14 and CSF opening pressures were determined at every sampling. The laboratory investigation schedule is provided in Section 2 in the Supplementary Appendix.

TREATMENT

Patients received either dexamethasone or identical placebo for 6 weeks as follows: intravenous administration of 0.3 mg per kilogram of body weight per day during the first week and 0.2 mg per kilogram per day during the second week, followed by oral administration of 0.1 mg per kilogram per day during the third week, 3 mg per day during the fourth week, 2 mg per day during the fifth week, and 1 mg per day during the sixth week. Patients received antifungal therapy according to international guidelines for regions in which flucytosine is unavailable.12 Induction therapy consisted of amphotericin B deoxycholate (Bharat Pharmaceuticals) at a dose of 1 mg per kilogram per day and fluconazole (Ranbaxy) at a dose of 800 mg per day for 2 weeks, followed by consolidation therapy (800 mg of fluconazole per day for 8 weeks) and then maintenance therapy (200 mg of fluconazole per day). The protocol initially recommended starting antiretroviral therapy 2 to 4 weeks after the initiation of antifungal treatment; this recommendation was updated to 5 weeks after the initiation of antifungal treatment after the publication of the results of the Cryptococcal Optimal ART (Antiretroviral Therapy) Timing (COAT) trial.15 All the patients received daily pneumocystis prophylaxis with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole.

ASSESSMENT OF OUTCOMES

The primary outcome was survival until 10 weeks after randomization. Secondary outcomes were survival until 6 months; the level of disability at 10 weeks and 6 months, with the outcome classified as good, intermediate, poor, or death6 (see Section 3 in the Supplementary Appendix); visual acuity at 10 weeks; the rate of decrease in cryptococcal counts in CSF; and the change in opening pressure during the first 2 weeks. We compared the incidence of new neurologic events, new acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)–defining illness, the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS), and any other grade 3 or 4 adverse event in the two study groups. Adverse events were assessed according to definitions in the protocol13 and categorized according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities system organ class.16

ETHICS AND STUDY OVERSIGHT

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and regulatory authority at each site and by the Oxford University tropical research ethics committee. An independent data and safety monitoring committee oversaw trial safety and analyzed unblinded data after every 50 deaths, according to its charter (Section 5 in the Supplementary Appendix). A trial steering committee consisting of three independent members, two study investigators, and an observer provided advice on the conduct of the trial. The funding bodies and drug manufacturers played no part in the study design, implementation, analysis, or manuscript preparation. All the authors made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication and vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and analyses presented.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Assuming an overall 10-week mortality of at least 30%, we determined that we would need to enroll at least 880 patients for the trial to have 80% power to detect a hazard ratio of 0.70 in favor of dexamethasone for the primary outcome, at a two-sided 5% significance level.13 All analyses were specified before unblinding, as detailed in the protocol13 and the statistical analysis plan (Section 4 in the Supplementary Appendix). In brief, we used a Cox proportional-hazards model with stratification according to continent to analyze survival in the intention-to-treat population and prespecified subgroups. Since testing on the basis of weighted Schoenfeld residuals provided clear evidence of nonproportional hazards, we also formally compared 10-week and 6-month survival probabilities between the two groups on the basis of Kaplan–Meier estimation and Greenwood’s formula to approximate variance. We used a logistic-regression model with the study group as the main covariate and with adjustment for continent to perform a between-group comparison of the probability of a good outcome with respect to disability status. Log10-transformed longitudinal quantitative measurements of fungal counts were modeled by means of a linear mixed-effects model, which treated undetectable measurements as left-censored. Statistical analyses were performed with the use of R software, version 3.1.2.17

RESULTS

TRIAL SUSPENSION

Recruitment began in February 2013. In August 2014, the data and safety monitoring committee recommended that the trial be stopped, a decision that was based on clinical judgment that dexamethasone was causing harm across key outcomes, including fungal clearance, adverse events, and disability outcomes, rather than on the basis of a prespecified stopping boundary having been crossed with respect to the primary outcome. We immediately suspended recruitment, and the trial was formally stopped in September 2014. All the patients completed 6 months of follow-up as planned.

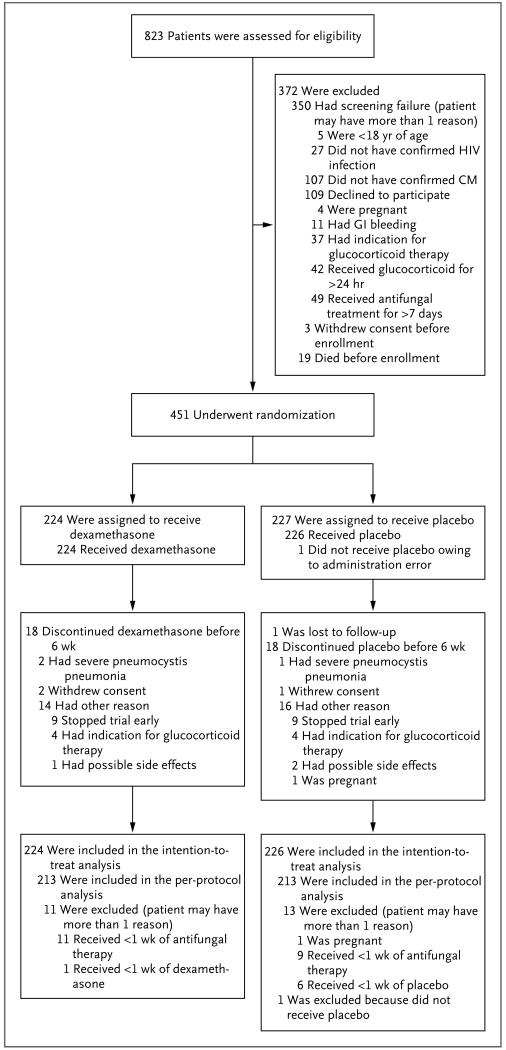

At the time of the suspension of the trial, we had screened 823 patients and enrolled 451, with 224 patients assigned to the dexamethasone group and 227 assigned to the placebo group (Fig. 1). During screening, 42 patients (including 41 in Asia) had already received more than 24 hours of glucocorticoid therapy and thus were not enrolled. In the intention-to-treat analysis, we excluded 1 patient in the placebo group who did not receive the assigned intervention because of a drug-administration error. We excluded 24 patients from the per-protocol analysis (Fig. 1). All the patients who were enrolled in the study received directly observed therapy for at least the first 2 weeks of treatment and while they were hospitalized. At discharge, all the patients received counseling and written instructions on the importance of completing dexamethasone therapy as prescribed. Out-patient assessments with medication review were performed weekly until 4 weeks and then at the completion of week 6 and week 10, unless more frequent review was indicated clinically. More than 99% of the planned dexamethasone doses were taken, according to this review.

Figure 1. Enrollment, Randomization, and Follow-up.

CM denotes cryptococcal meningitis, GI gastrointestinal, and HIV human immunodeficiency virus.

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

The characteristics of the patients at baseline were well balanced between the two study groups (Table 1). The Asian and African patients differed significantly with respect to some characteristics, including the prevalence of intravenous drug use (18% vs. 0%, P<0.001), cranial-nerve palsies (19% vs. 6%, P<0.001), visual impairment (21% vs. 12%, P = 0.02), the median CSF fungal load (4.80 vs. 3.83 log10 colony-forming units per milliliter, P<0.001), and the median CD4+ count (16 vs. 26 cells per cubic millimeter, P = 0.04). At baseline, Asian patients were less likely than African patients to have received previous antiretroviral therapy (23% vs. 55%, P<0.001).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline.*.

| Characteristic | Dexamethasone (N = 224) |

Placebo (N = 226) |

Residence in Africa (N = 246) |

Residence in Asia (N = 204) |

P Value for Comparison between Continents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence — no. (%) | |||||

| Africa | 122 (54) | 124 (55) | NA | NA | NA |

| Asia | 102 (46) | 102 (45) | NA | NA | NA |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 147 (66) | 132 (58) | 144 (59) | 135 (66) | 0.10 |

| Median age (IQR) — yr | 35 (31–41) | 35 (30–40) | 35 (30–41) | 35 (31–40) | 0.81 |

| History of intravenous drug use — no./total no. (%) | 17/215 (8) | 18/215 (8) | 0 | 35/196 (18) | <0.001 |

| Current antiretroviral-therapy status — no. (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| None | 135 (60) | 133 (59) | 111 (45) | 157 (77) | |

| ≤3 mo duration | 41 (18) | 46 (20) | 54 (22) | 33 (16) | |

| >3 mo duration | 48 (21) | 47 (21) | 81 (33) | 14 (7) | |

| Median illness duration (IQR) — days | 14 (7–21) | 14 (7–28) | 14 (7–30) | 13 (7–21) | 0.01 |

| Symptoms — no./total no. (%) | |||||

| Headache | 217/224 (97) | 212/226 (94) | 230/246 (93) | 199/204 (98) | 0.05 |

| Fever | 147/222 (66) | 134/223 (60) | 127/244 (52) | 154/201 (77) | <0.001 |

| Neck stiffness | 106/222 (48) | 103/219 (47) | 90/244 (37) | 119/197 (60) | <0.001 |

| Seizures | 35/223 (16) | 43/225 (19) | 33/245 (13) | 45/203 (22) | 0.02 |

| Abnormal visual acuity | 34/208 (16) | 32/205 (16) | 26/220 (12) | 40/193 (21) | 0.02 |

| Papilledema | 26/195 (13) | 23/195 (12) | 28/233 (12) | 21/157 (13) | 0.76 |

| Score on Glasgow Coma Scale — no./total no. (%)† | 0.21 | ||||

| ≤10 | 5/223 (2) | 9/226 (4) | 10/246 (4) | 4/203 (2) | |

| 11–14 | 31/223 (14) | 41/226 (18) | 44/246 (18) | 28/203 (14) | |

| 15 | 187/223 (84) | 176/226 (78) | 192/246 (78) | 171/203 (84) | |

| Cranial nerve palsy — no./total no. (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| None | 199/221 (90) | 185/215 (86) | 222/237 (94) | 162/199 (81) | |

| Cranial nerve VI | 10/221 (5) | 11/215 (5) | 3/237 (1) | 18/199 (9) | |

| Other cranial nerve | 12/221 (5) | 19/215 (9) | 12/237 (5) | 19/199 (10) | |

| Laboratory measures | |||||

| CSF opening pressure | |||||

| Median (IQR) — cm of CSF | 22 (15–32) | 24 (16–35) | 21 (16–31) | 25 (15–35) | 0.28 |

| >18 cm — no./total no. (%) | 129/200 (64) | 135/203 (67) | 139/213 (65) | 125/190 (66) | 0.92 |

| Median CSF white-cell count (IQR) — cells/mm3 | 20 (5–60) | 19 (5–55) | 15 (5–40) | 30 (8–92) | <0.001 |

| Median CSF glucose (IQR) — mmol/liter | 2.27 (1.54–2.87) | 2.34 (1.57–2.93) | 2.43 (1.75–2.96) | 2.11 (1.39–2.82) | 0.01 |

| Median blood glucose (IQR) — mmol/liter | 5.70 (4.99–6.60) | 5.60 (4.92–6.76) | 5.50 (4.80–6.27) | 6.05 (5.09–7.12) | <0.001 |

| Median CSF:blood glucose ratio (IQR) | 0.37 (0.24–0.48) | 0.39 (0.27–0.50) | 0.42 (0.27–0.52) | 0.34 (0.24–0.44) | <0.001 |

| Median CSF fungal count (IQR) — log10 CFU/ml | 4.25 (2.07–5.36) | 4.37 (2.56–5.55) | 3.83 (1.60–5.04) | 4.80 (3.16–5.78) | <0.001 |

| Median CD4+ count (IQR) — cells/mm3 | 18 (7–52) | 20 (7–52) | 26 (7–71) | 16 (8–40) | 0.04 |

| Median creatinine (IQR) — mg/dl | 0.72 (0.59–0.88) | 0.73 (0.58–0.92) | 0.70 (0.57–0.92) | 0.74 (0.60–0.89) | 0.41 |

There were no significant between-group differences at baseline (all P>0.10) according to Fisher’s exact test for categorical data or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous data. To convert the values for glucose to milligrams per deciliter, divide by 0.05551. To convert the values for creatinine to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4. CFU denotes colony-forming units, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, IQR interquartile range, and NA not applicable.

Scores on the Glascow Coma Scale range from 3 (deep coma) to 15 (normal consciousness).

PRIMARY OUTCOME

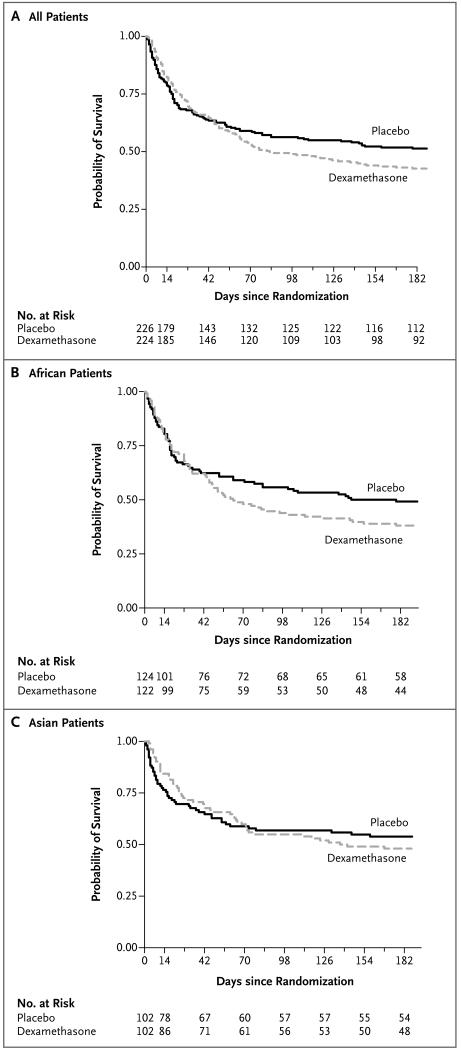

The key study outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Kaplan–Meier curves for survival up to 6 months for the whole study population and according to continent are shown in Figure 2. By 10 weeks (the cutoff time for the primary outcome), 106 of 224 patients (47%) in the dexamethasone group and 93 of 226 (41%) in the placebo group had died. The intention-to-treat analysis showed no significant between-group difference in survival at 10 weeks (hazard ratio for death in the dexamethasone group, 1.11; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.84 to 1.47; P = 0.45). However, tests for nonproportional hazards were highly significant, which suggested that the effect of dexamethasone changed over time. Therefore, we performed an exploratory analysis to determine hazard ratios at three discrete periods after randomization. The hazard ratios for death were 0.77 (95% CI, 0.54 to 1.09; P = 0.14) for days 1 to 22, 1.94 (95% CI, 0.97 to 3.88; P = 0.06) for days 23 through 43, and 2.50 (95% CI, 1.23 to 5.05; P = 0.01) for days 44 to 71 (Section 6 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 2. Primary and Key Secondary Outcomes.*.

| Outcome and Analysis Population | Dexamethasone (N = 224) |

Placebo (N = 226) |

Hazard Ratio or Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death by week 10: primary outcome — no./total no. (%)† | ||||

| Intention-to-treat population | 106/224 (47) | 93/226 (41) | 1.11 (0.84–1.47) | 0.45‡ |

| Per-protocol population | 103/213 (49) | 87/213 (41) | 1.16 (0.87–1.54) | 0.31§ |

| African patients | 63/122 (52) | 51/124 (42) | 1.26 (0.87–1.82) | 0.23¶ |

| Asian patients | 43/102 (42) | 42/102 (41) | 0.95 (0.62–1.45) | 0.80∥ |

| Score on Glasgow Coma Scale | ||||

| <15 | 23/36 (64) | 33/50 (66) | 0.86 (0.51–1.48) | 0.60 |

| 15 | 82/187 (44) | 60/176 (34) | 1.29 (0.93–1.80) | 0.13 |

| Antiretroviral therapy status at baseline | ||||

| None | 68/135 (50) | 57/133 (43) | 1.15 (0.81–1.63) | 0.45 |

| Duration ≤3 mo | 21/41 (51) | 16/46 (35) | 1.49 (0.77–2.87) | 0.23 |

| Duration >3 mo | 17/48 (36) | 20/47 (43) | 0.77 (0.40–1.47) | 0.43 |

| Quantitative fungal count | ||||

| ≤105 CFU/ml | 63/141 (45) | 47/131 (36) | 1.24 (0.85–1.81) | 0.26 |

| >105 CFU/ml | 35/63 (56) | 42/81 (53) | 0.99 (0.63–1.56) | 0.98 |

| CSF opening pressure >18 cm | 64/129 (50) | 57/135 (43) | 1.14 (0.80–1.63) | 0.47 |

| CSF white-cell count <5 cells/mm3 | 11/25 (44) | 12/17 (71) | 0.53 (0.23–1.21) | 0.13 |

| Death by 6 mo — no./total no. (%)† | ||||

| Intention-to-treat population | 128/224 (57) | 109/226 (49) | 1.18 (0.91–1.53) | 0.20‡ |

| Per-protocol population | 125/213 (59) | 103/213 (48) | 1.23 (0.95–1.60) | 0.12§ |

| African patients | 75/122 (62) | 62/124 (51) | 1.28 (0.91–1.79) | 0.16¶ |

| Asian patients | 53/102 (52) | 47/102 (46) | 1.06 (0.72–1.58) | 0.76∥ |

| Disability at 10 wk in intention-to-treat population — no./total no. (%) | ||||

| Good outcome** | 28/222 (13) | 55/220 (25) | 0.42 (0.25–0.69) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate outcome | 53/222 (24) | 46/220 (21) | ||

| Severe disability | 35/222 (16) | 26/220 (12) | ||

| Death | 106/222 (48) | 93/220 (42) | ||

| Disability at 6 mo in intention-to-treat population — no./total no. (%) | ||||

| Good outcome†† | 40/223 (18) | 68/223 (30) | 0.49 (0.31–0.77) | 0.002 |

| Intermediate outcome | 40/223 (18) | 34/223 (15) | ||

| Severe disability | 15/223 (7) | 12/223 (5) | ||

| Death | 128/223 (57) | 109/223 (49) | ||

| Difference in Estimated Change (95% CI) | ||||

| Estimated decrease in CSF fungal count during first 14 days (95% CI) — log10 CFU/ml per day | ||||

| Intention-to-treat population | −0.21 (−0.24 to −0.19) | −0.31 (−0.34 to −0.28) | 0.09 (0.06 to 0.13) | <0.001 |

| African patients | −0.20 (−0.24 to −0.17) | −0.28 (−0.32 to −0.24) | 0.07 (0.03 to 0.12) | 0.002 |

| Asian patients | −0.22 (−0.26 to −0.19) | −0.35 (−0.39 to −0.30) | 0.12 (0.07 to 0.18) | <0.001 |

| Absolute decrease in CSF opening pressure during first 14 days (95% CI) — cm of CSF | ||||

| Intention-to-treat population | −9.2 (−11.9 to −6.5) | −3.2 (−5.8 to −0.5) | −6.1 (−9.4 to −2.7) | <0.001 |

| African patients | −10.7 (−14.3 to −7.0) | −5.5 (−9.0 to −2.1) | −5.1 (−9.4 to −0.8) | 0.02 |

| Asian patients | −7.7 (−11.7 to −3.8) | 0.1 (−4.1 to 4.2) | −7.8 (−12.9 to −2.6) | 0.003 |

Hazard ratios were calculated for death, and odds ratios for disability. CI denotes confidence interval.

Risks were estimated by means of the Kaplan–Meier method, so percentages may not calculate mathematically.

According to the test for proportional hazards, P<0.001 by 10 weeks and P = 0.001 by 6 months. The estimated absolute difference in the risk of death was 6.01 percentage points (95% CI, −3.19 to 15.20; P = 0.20) at 10 weeks and 8.68 percentage points (95% CI, −0.54 to 17.90; P = 0.07) at 6 months.

According to the test for proportional hazards, P<0.001 by 10 weeks and by 6 months. The estimated absolute difference in the risk of death was 7.61 percentage points (95% CI, −1.82 to 17.05; P = 0.11) at 10 weeks and 10.50 percentage points (95% CI, 1.07 to 19.94; P = 0.03) at 6 months.

According to the test for proportional hazards, P = 0.03 by 10 weeks and P = 0.08 by 6 months. The estimated absolute difference in the risk of death was 10.23 percentage points (95% CI, −2.25 to 22.71; P = 0.11) at 10 weeks and 11.13 percentage points (95% CI, −1.27 to 23.52; P = 0.08) at 6 months.

According to the test for proportional hazards, P = 0.01 by 10 weeks and P = 0.004 by 6 months. The estimated absolute difference in the risk of death was 0.98 percentage points (95% CI, −12.55 to 14.51; P = 0.89) at 10 weeks and 5.80 percentage points (95% CI, −7.91 to 19.51; P = 0.41) at 6 months.

At 10 weeks, the odds ratios for a good outcome were 0.43 (95% CI, 0.18 to 0.97; P = 0.04) for African patients and 0.41 (95% CI, 0.21 to 0.77; P = 0.005) for Asian patients.

At 6 months, the odds ratios for a good outcome were 0.63 (95% CI, 0.32 to 1.19; P = 0.15) for African patients and 0.40 (95% CI, 0.21 to 0.73; P = 0.003) for Asian patients.

Figure 2. Survival among All Patients and According to Continent.

Shown are Kaplan–Meier survival estimates for all patients (Panel A) and for those in Africa (Panel B) and Asia (Panel C) during the 6 months of follow-up. By 10 weeks (the cutoff for the primary outcome), 106 of 224 patients (47%) in the dexamethasone group and 93 of 226 (41%) in the placebo group had died. At 6 months, the estimated risks of death were 57% and 49%, respectively.

MORTALITY BY 6 MONTHS

By 6 months, 128 of 224 patients in the dexamethasone group, as compared with 109 of 226 patients in the placebo group, had died; the associated Kaplan–Meier mortality estimates were 57% and 49%, respectively. The prespecified Cox regression time-to-event analysis of mortality did not show a significant between-group difference (hazard ratio, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.91 to 1.53; P = 0.20). However, a formal comparison of the risk of death at 6 months showed a trend toward harm in the dexamethasone group, with an absolute increase in risk of 9 percentage points (95% CI, −1 to 18; P = 0.07) in the intention-to-treat population and of 11 percentage points (95% CI, 1 to 20; P = 0.03) in the per-protocol population.

DISABILITY

Dexamethasone was associated with a significantly higher risk of death or disability than was placebo at both 10 weeks and 6 months, with odds ratios for a good outcome of 0.42 (95% CI, 0.25 to 0.69; P<0.001) at 10 weeks and 0.49 (95% CI, 0.31 to 0.77; P = 0.002) at 6 months. Results were consistent across continents (Table 2). The prespecified analyses of visual impairment among 234 survivors at 10 weeks indicated that normal visual acuity was less common among those receiving dexamethasone than among those receiving placebo (88% [94 of 107 patients] vs. 96% [122 of 127 patients]; odds ratio, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.09 to 0.84; P = 0.02). However, an exploratory analysis that excluded the 37 survivors who had visual abnormalities at baseline showed no significant between-group difference (odds ratio, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.10 to 2.20; P = 0.37).

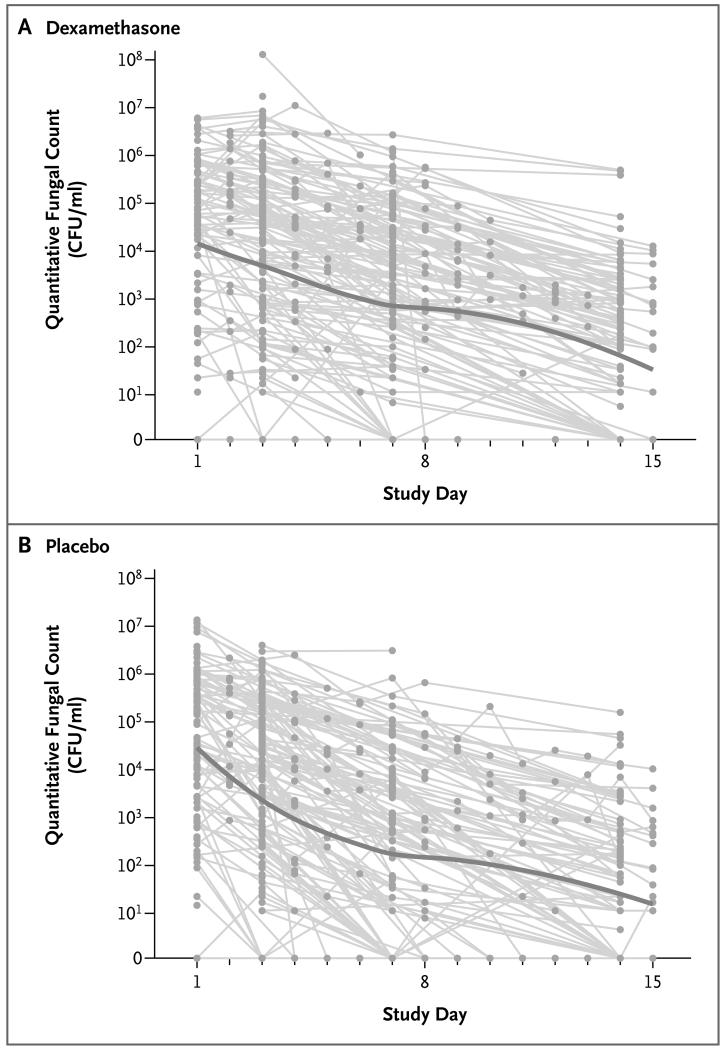

EARLY FUNGICIDAL ACTIVITY

Dexamethasone was associated with significantly slower rates of decline in the number of cryptococcal colony-forming units in CSF than was placebo during the first 2 weeks of treatment (Fig. 3). The rate of decline per day was −0.21 log10 colony-forming units per milliliter (95% CI, −0.24 to −0.19) in the dexamethasone group versus −0.31 log10 colony-forming units per milliliter (95% CI, −0.34 to −0.28) in the placebo group (P<0.001) (Table 2). The numbers of patients with relapse were similar in the two groups (5 in the dexamethasone group and 7 in the placebo group). A detailed definition of relapse is provided in Section 7 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Figure 3. Quantitative Fungal Counts in Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF).

Shown are the CSF quantitative fungal counts in the dexamethasone group (Panel A) and placebo group (Panel B). Study day 1 corresponds to the day of randomization. All recorded CSF quantitative counts are shown, including those in patients who subsequently died. The gray lines indicate data for individual patients, and the solid line shows scatterplot smoothing based on local regression. The decrease in CSF fungal counts, as measured in colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter, during the first 14 days was significantly slower among patients in the dexamethasone group than among those in the placebo group.

CLINICAL ADVERSE EVENTS

By 6 months, there were 667 clinical adverse events in the dexamethasone group and 494 in the placebo group (P = 0.01). A summary of adverse events is provided in Table 3, and a detailed listing is provided in Section 8 in the Supplementary Appendix.

Table 3.

Adverse Events by 6 Months.*

| Event | Dexamethasone (N = 224) | Placebo (N = 226) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| no. of patients (%) | |||

| Clinical adverse events | |||

| At least one event† | 193 (86) | 191 (85) | 0.69 |

| New neurologic event | 61 (27) | 59 (26) | 0.83 |

| New AIDS-defining illness | 87 (39) | 87 (38) | 1.00 |

| Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome | 7 (3) | 6 (3) | 0.79 |

| Metabolism or nutrition disorder | 78 (35) | 85 (38) | 0.56 |

| Blood or lymphatic system disorder | 96 (43) | 83 (37) | 0.21 |

| Infection or infestation | 48 (21) | 25 (11) | 0.003 |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 29 (13) | 16 (7) | 0.04 |

| Renal or urinary disorder | 22 (10) | 7 (3) | 0.004 |

| Respiratory, thoracic, or mediastinal disorder | 9 (4) | 14 (6) | 0.39 |

| Hepatobiliary disorder | 10 (4) | 3 (1) | 0.05 |

| Vascular disorder | 9 (4) | 4 (2) | 0.17 |

| Skin or subcutaneous-tissue disorder | 6 (3) | 3 (1) | 0.34 |

| Cardiac disorder | 8 (4) | 0 | 0.004 |

| Endocrine disorder | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 1.00 |

| Psychiatric disorder | 3 (1) | 1 (<1) | 0.37 |

| Immune system disorder | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 1.00 |

| Injury, poisoning, or procedural complication | 2 (1) | 1 (<1) | 0.62 |

| Reproductive system or breast disorder | 1 (<1) | 0 | 0.50 |

| Pregnancy, puerperium, or perinatal condition | 0 | 1 (<1) | 1.00 |

| Systemic disorder | 0 | 1 (<1) | 1.00 |

| Grade 3 or 4 laboratory adverse events | |||

| Any event‡ | 202 (90) | 192 (85) | 0.12 |

| Anemia | 120 (54) | 112 (50) | 0.40 |

| Leukocytopenia | 36 (16) | 41 (18) | 0.62 |

| Neutropenia | 42 (19) | 59 (26) | 0.07 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 33 (15) | 25 (11) | 0.26 |

| Elevated alanine aminotransferase | 10 (4) | 3 (1) | 0.05 |

| Elevated aspartate aminotransferase | 14 (6) | 11 (5) | 0.54 |

| Hyperglycemia | 32 (14) | 6 (3) | <0.001 |

| Hypoglycemia | 5 (2) | 6 (3) | 1.00 |

| Hypercreatinemia | 79 (35) | 50 (22) | 0.002 |

| Hyperkalemia | 52 (23) | 19 (8) | <0.001 |

| Hypokalemia | 108 (48) | 132 (58) | 0.04 |

| Hypernatremia | 2 (1) | 7 (3) | 0.18 |

| Hyponatremia | 114 (51) | 75 (33) | <0.001 |

Listed are the numbers of patients who had at least one adverse event of the respective type. All comparisons are based on Fisher’s exact test, except for comparisons of the total number of adverse events, for which the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the number of events per patient. AIDS denotes acquired immunodeficiency syn drome.

The total number of clinical events was 667 in the dexamethasone group and 494 in the placebo group (P = 0.01).

The total number of grade 3 or 4 laboratory events was 1023 in the dexamethasone group and 835 in the placebo group (P = 0.02).

A total of 87 patients in each group had a new AIDS-defining illness. However, the rate of the combined outcome of a new AIDS-defining illness or death by 6 months was higher in the dexamethasone group than in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.58; P = 0.05). Adverse events that were categorized as infections or infestations occurred in 48 patients (21%) in the dexamethasone group and in 25 (11%) in the placebo group (P = 0.003). Patients in the dexamethasone group had more adverse events than those in the placebo group with respect to gastrointestinal disorders (29 [13%] vs. 16 [7%], P = 0.04), renal or urinary disorders (22 [10%] vs. 7 [3%], P = 0.004), and cardiac disorders (8 [4%] vs. 0, P = 0.004). Gastrointestinal bleeding was uncommon, and rates were similar in the two groups. There were 19 cases of acute renal failure in the dexamethasone group and 7 in the placebo group; in the dexamethasone group, 15 of the 19 cases (79%) occurred during an infectious episode. The rates of paradoxical IRIS (i.e., clinical deterioration that occurs after the initiation of antiretroviral therapy despite a microbiologic response to antifungal therapy) at 10 weeks and 6 months were similar in the two study groups. The median time from study entry until the initiation of antiretroviral therapy was 46 days in the dexamethasone group and 42 days in the placebo group.

LABORATORY ADVERSE EVENTS

By 6 months, there were 1023 grade 3 or 4 laboratory adverse events in the dexamethasone group and 835 in the placebo group (P = 0.02) (Table 3). Hyperglycemia, hypercreatinemia, hyperkalemia, and hyponatremia all occurred significantly more frequently among patients receiving dexamethasone than among those receiving placebo.

CSF OPENING PRESSURE

Dexamethasone was associated with a larger reduction in CSF opening pressure during the first 2 weeks than was placebo. The estimated change was −9.2 cm of CSF (95% CI, −11.9 to −6.5) in the dexamethasone group and −3.2 cm of CSF (95% CI, −5.8 to −0.5) in the placebo group (P<0.001) (Table 2).

SUBGROUP ANALYSES

Prespecified subgroup analyses showed no significant between-group differences in 10-week mortality in any of the subgroups — those defined according to continent, country, sex, baseline score on the Glasgow Coma Scale, anti-retroviral-therapy status, age, fungal burden, CD4+ count, baseline CSF opening pressure, and CSF white-cell count. No evidence of heterogeneity of effect was seen (Section 9 in the Supplementary Appendix).

DISCUSSION

We set out to test whether adjunctive treatment with dexamethasone, initiated at the time of diagnosis, would be beneficial for all patients with HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. We found compelling evidence that at the dose and regimen used in the study such use was harmful, with significantly increased rates of disability and excess severe adverse events, including infectious episodes and renal, gastrointestinal, and cardiac disorders. The study was stopped early because of consistent evidence of harm across several outcomes. Consequently, the study did not have the statistical power to show an effect of dexamethasone on the primary outcome of mortality at 10 weeks. However, consistent with the evidence of harm, the hazard ratios for survival at 10 weeks and 6 months did not favor dexamethasone, and a formal between-group comparison of the risk of death at 6 months was suggestive of harm (P = 0.07) and reached significance in the per-protocol analysis (P = 0.03). Therefore, it is highly unlikely that dexamethasone benefits survival in such patients. The consistency of findings across Asian and African populations and all prespecified subgroups strengthens this conclusion.

We had hypothesized that dexamethasone would improve outcomes by reducing intracranial pressure and inflammatory complications and by decreasing the incidence of IRIS. The CSF opening pressure decreased more rapidly in patients receiving dexamethasone, but no survival benefit was seen, even among patients with increased pressures at baseline. Tests for proportional hazards suggested that the effect of dexamethasone may be time-dependent, and our exploratory analysis suggested that dexamethasone may have benefit during the first 3 weeks of treatment — a possible reflection of modulation of pressure. A shorter duration of dexamethasone might have resulted in a different outcome. However, overall, the effects of dexamethasone are negative.

IRIS is a difficult management problem in cryptococcal meningitis. Current guidelines suggest that the use of glucocorticoids may be beneficial.12,18 Almost 20% of the patients had initiated antiretroviral therapy in the 3 months before study entry. It is likely that these patients had occult cryptococcal infection that was revealed and worsened by immune reconstitution induced by antiretroviral therapy (so-called unmasking IRIS).19 Even in this subgroup, we found no suggestion of benefit with dexamethasone therapy. Paradoxical IRIS occurred in 13 patients, and the study did not have the power to detect any effect of dexamethasone on this outcome. However, prespecified subgroup analyses for factors that have been associated with an increased risk of paradoxical IRIS (low CD4+ count, low CSF cellularity, and high CSF fungal burden18,20) did not identify a beneficial effect of dexamethasone.

It is not clear why dexamethasone was harmful. We chose an administration schedule that is routinely used among similarly immunosuppressed patients with HIV infection and tuberculous meningitis in Vietnam. Among patients with tuberculous meningitis, this administration schedule is associated with a lower risk of adverse events than that among patients receiving placebo.6,21,22 In our study, the dexamethasone group had slower rates of decline in cryptococcus counts in CSF than the placebo group, and a slower rate of decline has been associated with worse outcomes.23 Increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines at baseline have been associated with faster clearance of CSF cryptococcus and improved survival. It might be expected that cytokine levels would be attenuated by dexamethasone.24-26 However, in the dexamethasone trial involving patients with tuberculous meningitis, no effect on cytokine levels was seen.27 In our study, the increased risk of other acute infections in the dexamethasone group may have contributed to the harm that was observed. Most cases of acute renal failure in this group were associated with severe infections and were probably a consequence of sepsis rather than the use of dexamethasone.

In conclusion, we tested an adjunctive immune-modulating treatment for cryptococcal meningitis because of a lack of new antifungal agents and the poor performance of those currently available. This pragmatic trial was designed to determine whether treatment with adjuvant glucocorticoids, started at the point of diagnosis, would improve survival among patients with HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. We found that it did not. However, even though we have shown that a universal approach to the use of dexamethasone in patients with HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis is harmful, there may still be a role for glucocorticoids in such patients. Current guidelines recommend the use of glucocorticoids among patients who have cryptococcomas with mass effect, the acute respiratory distress syndrome, or IRIS. These events were infrequent in our study. Therefore, our study did not have the power to test these particular indications, and generating high-quality evidence to test these indications will be difficult. It should be noted that 11% of all the patients who were excluded from the study did not participate because they had received glucocorticoids for CNS disease. Here, we have shown that such use is not justified. With no effective adjunctive therapy yet identified, improving access to the most effective antifungal treatments, including flucytosine, must remain a global priority.2,3,28,29

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the United Kingdom Department for International Development, the Wellcome Trust, and the Medical Research Council through a grant (G1100684/1) from the Joint Global Health Trials program, which is part of the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership, supported by the European Union; and by an intermediate fellowship (through grant no. WT097147MA, to Dr. Day) from the Wellcome Trust.

We thank the trial participants and the clinical, administrative, and laboratory staff members at all sites; the members of the data and safety monitoring committee (Diederik van de Beek, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam; Janet Derbyshire, University College London, London; Ronald Geskus, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam; Andrew Kambugu, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda; and David Mabey, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London); and the independent members of the trial steering committee (David Cooper, University of New South Wales, Sydney; Robin Bailey, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London; Robin Grant, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh; and Jimmy Whitworth, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London) for their advice and support.

APPENDIX

The authors’ full names and academic degrees are as follows: Justin Beardsley, M.B., Ch.B., Marcel Wolbers, Ph.D., Freddie M. Kibengo, M.Med., Abu-Baker M. Ggayi, M.Sc., Anatoli Kamali, Ph.D., Ngo Thi Kim Cuc, M.D., Tran Quang Binh, M.D., Ph.D., Nguyen Van Vinh Chau, M.D., Ph.D., Jeremy Farrar, D.Phil., Laura Merson, B.Sc., Lan Phuong, M.D., Ph.D., Guy Thwaites, Ph.D., Nguyen Van Kinh, M.D., Ph.D., Pham Thanh Thuy, M.D., Ph.D., Wirongrong Chierakul, M.D., Ph.D., Suwatthiya Siriboon, M.D., Ekkachai Thiansukhon, M.D., Satrirat Onsanit, M.D., Watthanapong Supphamongkholchaikul, M.D., Adrienne K. Chan, M.D., Robert Heyderman, Ph.D., Edson Mwinjiwa, C.O., Joep J. van Oosterhout, M.D., Ph.D., Darma Imran, M.D., Hasan Basri, M.D., Mayfong Mayxay, M.D., David Dance, F.R.C.Path., Prasith Phimmasone, M.D., Sayaphet Rattanavong, M.D., David G. Lalloo, M.D., and Jeremy N. Day, Ph.D., for the CryptoDex Investigators

The authors’ affiliations are as follows: the Oxford University Clinical Research Unit, Wellcome Trust Major Overseas Programme Vietnam (J.B., M.W., J.F., L.M., G.T., J.N.D.), Hospital for Tropical Diseases (N.T.K.C., N.V.V.C.), Cho Ray Hospital (T.Q.B., L.P.), Ho Chi Minh City, and the National Hospital for Tropical Diseases (N.V.K.) and Bach Mai Hospital (P.T.T.), Hanoi — all in Vietnam; Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, University of Oxford, Oxford (J.B., M.W., J.F., L.M., G.T., M.M., D.D., J.N.D.), University College London, London (R.H.), and Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool (D.G.L.) — all in the United Kingdom; MRC/UVRI Uganda Research Unit on AIDS, Entebbe, Uganda (F.M.K., A.-B.M.G., A.K.); Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, Mahidol University, Bangkok (W.C.), Ubon Sappasithiprasong Hospital, Ubon (S.S., W.S.), and Udon Thani Hospital, Udon Thani (E.T., S.O.) — all in Thailand; Dignitas International, Zomba (A.K.C., E.M., J.J.O.), and Malawi–Liverpool–Wellcome Trust, Clinical Research Programme (R.H., D.G.L.), and University of Malawi College of Medicine (R.H., J.J.O.), Blantyre — all in Malawi; Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, University of Toronto, Toronto (A.K.C.); Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital (D.I.) and Eijkman Oxford Clinical Research Unit (H.B.) — both in Jakarta, Indonesia; and Lao–Oxford–Mahosot Hospital–Wellcome Trust Research Unit, Mahosot Hospital (M.M., D.D., P.P., S.R.), and University of Health Sciences (M.M.) — both in Vientiane, Laos.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, Chiller TM. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2009;23:525–30. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Horst CM, Saag MS, Cloud GA, et al. Treatment of cryptococcal meningitis associated with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:15–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707033370103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Day JN, Chau TTH, Wolbers M, et al. Combination antifungal therapy for cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1291–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Gans J, van de Beek D. Dexamethasone in adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1549–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen THM, Tran THC, Thwaites G, et al. Dexamethasone in Vietnamese adolescents and adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2431–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thwaites GE, Nguyen DB, Nguyen HD, et al. Dexamethasone for the treatment of tuberculous meningitis in adolescents and adults. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1741–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casadevall A, Perfect JJR. Cryptococcus neoformans. American Society for Microbiology; Washington, DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scarborough M, Gordon SB, Whitty CJM, et al. Corticosteroids for bacterial meningitis in adults in sub-Saharan Africa. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2441–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seaton RA, Verma N, Naraqi S, Wembri JP, Warrell DA. The effect of corticosteroids on visual loss in Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii meningitis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:50–2. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90393-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Soto-Hernandez JL, Angeles-Morales V, et al. Effects of pentoxifylline or dexamethasone in combination with amphotericin B in experimental murine cerebral cryptococcosis: evidence of neuroexcitatory pathogenic mechanisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1194–7. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lortholary O, Nicolas M, Soreda S, et al. Fluconazole, with or without dexamethasone for experimental cryptococcosis: impact of treatment timing. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:817–24. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.6.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291–322. doi: 10.1086/649858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Day J, Imran D, Ganiem AR, et al. CryptoDex: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of adjunctive dexamethasone in HIV-infected adults with cryptococcal meningitis: study protocol for a randomised control trial. Trials. 2014;15:441. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brouwer AE, Rajanuwong A, Chierakul W, et al. Combination antifungal therapies for HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1764–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulware DR, Meya DB, Muzoora C, et al. Timing of antiretroviral therapy after diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2487–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use; MedDRA; http://www.meddra.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2014. http://www.r-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sungkanuparph S, Filler SG, Chetchotisakd P, et al. Cryptococcal immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome after antiretroviral therapy in AIDS patients with cryptococcal meningitis: a prospective multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:931–4. doi: 10.1086/605497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haddow LJ, Colebunders R, Meintjes G, et al. Cryptococcal immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-1-infected individuals: proposed clinical case definitions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:791–802. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70170-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lortholary O, Fontanet A, Mémain N, Martin A, Sitbon K, Dromer F. Incidence and risk factors of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome complicating HIV-associated cryptococcosis in France. AIDS. 2005;19:1043–9. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000174450.70874.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Török ME, Yen NTB, Chau TTH, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) — associated tuberculous meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1374–83. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heemskerk D, Day J, Chau TTH, et al. Intensified treatment with high dose rifampicin and levofloxacin compared to standard treatment for adult patients with tuberculous meningitis (TBM-IT): protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12:25. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bicanic T, Muzoora C, Brouwer AE, et al. Independent association between rate of clearance of infection and clinical outcome of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: analysis of a combined cohort of 262 patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:702–9. doi: 10.1086/604716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarvis JN, Meintjes G, Rebe K, et al. Adjunctive interferon-γ immunotherapy for the treatment of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS. 2012;26:1105–13. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283536a93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarvis JN, Meintjes G, Bicanic T, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid cytokine profiles predict risk of early mortality and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(4):e1004754. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elenkov IJ. Glucocorticoids and the Th1/Th2 balance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1024:138–46. doi: 10.1196/annals.1321.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simmons CP, Thwaites GE, Quyen NTH, et al. The clinical benefit of adjunctive dexamethasone in tuberculous meningitis is not associated with measurable attenuation of peripheral or local immune responses. J Immunol. 2005;175:579–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loyse A, Thangaraj H, Easterbrook P, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: improving access to essential antifungal medicines in resource-poor countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:629–37. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loyse A, Dromer F, Day J, Lortholary O, Harrison TS. Flucytosine and cryptococcosis: time to urgently address the worldwide accessibility of a 50-year-old antifungal. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:2435–44. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.