Abstract

Genes encoding human β-type globin undergo a developmental switch from embryonic to fetal to adult-type expression. Mutations in the adult form cause inherited hemoglobinopathies or globin disorders, including sickle cell disease and thalassemia. Some experimental results have suggested that these diseases could be treated by induction of fetal-type hemoglobin (HbF). However, the mechanisms that repress HbF in adults remain unclear. We found that the LRF/ZBTB7A transcription factor occupies fetal γ-globin genes and maintains the nucleosome density necessary for γ-globin gene silencing in adults, and that LRF confers its repressive activity through a NuRD repressor complex independent of the fetal globin repressor BCL11A. Our study may provide additional opportunities for therapeutic targeting in the treatment of hemoglobinopathies.

During human development, the site of erythropoiesis changes from the embryonic yolk sac to the fetal liver and then, in newborns, to the bone marrow, where it persists through adulthood. Coincidentally, there is a “globin switch” from embryonic to fetal globin genes in utero, and then a second switch from fetal to adult globin expression soon after birth. This process has been studied for more than 60 years (1). The latter transition from fetal to adult hemoglobin is marked by a switch from a fetal tetramer consisting of two α and two γ subunits (HbF: α2γ2) to an adult tetramer containing two α-like and two β-like globin subunits (HbA: α2β2).

Mutations in the adult globin gene cause hemoglobinopathies such as thalassemia and sickle cell disease (SCD). These diseases are among the most common monogenic inherited human disorders and represent emerging public health challenges (2). For example, the number of children born with SCD is expected to exceed 14 million worldwide in the next 40 years (3).

Molecular genetic and clinical evidence indicates that elevated levels of fetal-type hemoglobin (HbF) in adults ameliorate SCD and β-thalassemia pathogenesis (1, 4). Thus, a promising approach is to pharmacologically inactivate a silencer(s) of fetal globin expression in order to reactivate HbF production in adult erythroid cells. Nuclear factors that regulate globin switching have been identified, but how they function cooperatively or independently in fetal globin repression is not fully understood.

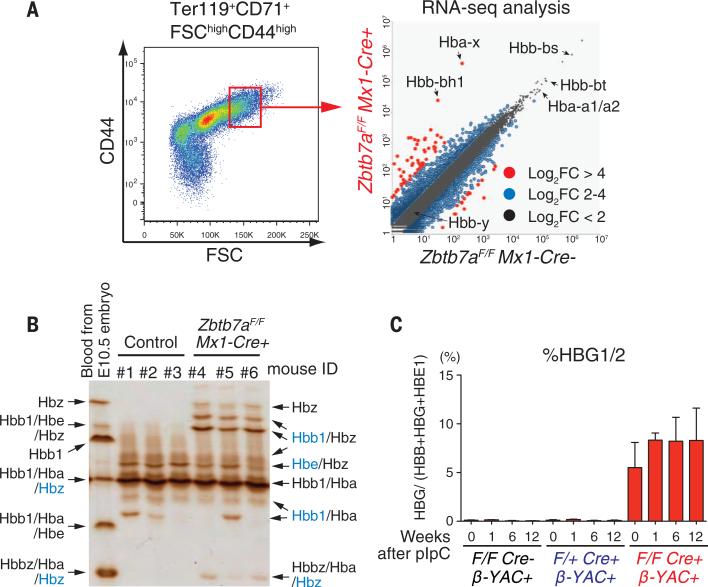

Leukemia/lymphoma-related factor (LRF), encoded by the ZBTB7A gene, is a ZBTB transcription factor that binds DNA through C-terminal C2H2-type zinc fingers and presumably recruits a transcriptional repressor complex through its N-terminal BTB domain (5). To assess the effects of LRF loss on the erythroid transcriptome, we inactivated the Zbtb7a gene in erythroid cells of adult mice (6). We then performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis using splenic erythroblasts from control and LRF conditional knockout (Zbtb7aF/F Mx1-Cre+) mice (LRF KO mice) (Fig. 1A). Efficient Zbtb7a deletion was confirmed by Western blot and RNA-Seq reads (fig. S1, A and B) (7). Wild-type mice express two embryonic β-like globin genes: Hbb-bh1 and Hbb-y (8, 9). Although both genes are expressed at early embryonic stages, Hbb-bh1 is the ortholog of human γ-globin (10, 11). LRF-deficient adult erythroblasts showed significant induction of Hbb-bh1, but not Hbb-y, with a moderate reduction in adult globin levels (fig. S2A). These results were validated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) (fig. S2B). Isoelectric focusing of peripheral blood hemolysates revealed unique bands corresponding to embryonic globin proteins in peripheral blood from LRF KO mice (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1. Induced Zbtb7a deletion reactivates embryonic/fetal globin expression in adult mice.

(A) RNA-seq analysis of splenic erythroblasts from control and LRF KO mice. Mice were injected with polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid, and splenic erythroblasts were harvested 2 months later. Each dot represents an individual gene; differentially expressed genes are depicted according to FPM (fragments per million mapped reads) values. (B) Isoelectric focusing of peripheral blood hemolysates and subsequent peptide mass fingerprinting with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). Embryonic globins (Hbz and Hbbz) are evident in samples from LRF KO mice. Globins shown in blue were detected at a much lower level. (C) Levels of human γ-globin (HBG) transcripts were monitored by qPCR before and after LRF depletion. Error bars denote SD. We observed a low level of γ-globin expression before induction of LRF KO, likely due to leaky Cre activity (24).

We used a humanized mouse model to investigate whether LRF loss would reactivate human fetal globin expression in vivo. To do so, we established LRF KO mice harboring the human β-globin gene cluster as a yeast artificial chromosome transgene (βYAC) (12) (fig. S2C). Human γ-globin transcripts, but not those of embryonic β-globin (HBE1), were significantly induced in LRF-deficient erythroblasts and constituted 6 to 12% of total human β-like globins in peripheral blood (Fig. 1C and fig. S2D). The magnitude of γ-globin induction in LRF/bYAC mice approximated that seen in BCL11A/βYAC mice (13).

We next determined whether LRF loss could induce HbF in human erythroid cells. To this end, we used human CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC)–derived primary erythroblasts and determined γ-globin expression levels upon short hairpin RNA (shRNA)–mediated LRF knockdown (LRF KD) (fig. S3A). LRF expression was markedly induced upon erythroid differentiation over a 2-week period (Fig. 2A). LRF KD significantly increased the percentage of γ-globin mRNA (Fig. 2B and fig. S3, B and C) and protein expression (fig. S3D) relative to adult globin. HbF levels in LRF KD cells were greater than those seen in parental or scrambled-shRNA transduced cells (Fig. 2C and fig. S3E). Because LRF KO mice exhibit a mild macrocytic anemia due to inefficient erythroid terminal differentiation (14), we assessed the effects of LRF deficiency on human erythroid differentiation. We observed a delay in differentiation upon LRF KD relative to controls (fig. S4A and supplementary text).

Fig. 2. ZBTB7A deletion reactivates γ-globin expression in human erythroblasts.

(A) Time course analysis of LRF and BCL11A protein levels by Western blot. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Bar graphs show proportions of γ-globin to total β-globin transcripts measured by qPCR on day 15. (C) Bar graphs show proportions of HbF relative to adult globin (HbA0) on day 15. Means of two independent samples per condition are shown. Error bars denote SD. (D) RNA-seq analysis of control and LRF KO HUDEP-2 cells. Differentially expressed genes are indicated according to FPM values. (E) Representative HPLC profiles of control and ZBTB7AΔ/Δ HUDEP-2 clones. Control: HUDEP-2_Cas9.

HSPC-derived erythroid cells tend to display relatively high basal levels of HbF (Fig. 2C). Moreover, it is difficult to exclude the possibility that the effects of LRF KD may be the result of a sub-population of cells expressing aberrantly high HbF levels. To circumvent these problems, we used a human immortalized erythroid line (HUDEP-2), which undergoes terminal differentiation upon doxycycline removal (fig. S5A) (15). This line possesses an advantage over lines currently used for globin switching studies because it expresses predominantly adult hemoglobin (HbA), with very low background HbF expression (15). Using CRISPR/cas9 gene modification, we knocked out ZBTB7A in HUDEP-2 cells (fig. S5B). We did not observe a significant difference in erythroid differentiation between control and ZBTB7A KO HUDEP-2 cells, as evidenced by morphologic and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses (fig. S5, C and D). To evaluate genome-wide gene expression changes promoted by ZBTB7A deletion, we performed RNA-seq analysis. Wild-type HUDEP-2 cells exhibited gene expression patterns similar to those of HSPC-derived basophilic erythroblasts (fig. S6). As expected, γ-globin transcripts, but not those of embryonic ε-globin, were markedly induced in ZBTB7A KO HUDEP-2 cells (Fig. 2D and fig. S7A). Levels of adult β-globin transcripts in ZBTB7A KO cells were approximately half those seen in control cells (fig. S7A); γ-globin transcripts constituted more than 60% of total β-like globins (fig. S7B). Induction of γ-globin was also validated at the protein level (fig. S7, C and D). We then established three independent ZBTB7A KO HUDEP-2 clones (fig. S7E) and determined HbF levels in each by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). All three clones exhibited HbF levels greater than 60%, whereas that of parental cells was less than 3% (Fig. 2E). Notably, the HbF reactivation occurred without changes in levels of transcripts encoding known HbF repressors, including BCL11A (fig. S7F). BCL11A protein levels were also unchanged in ZBTB7A KO cells (fig. S5B).

To determine LRF occupancy sites genome-wide, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation and sequencing (ChIP-seq) with an antibody to LRF, using HSPC-derived proerythroblasts and HUDEP-2 cells. These experiments exhibited strong correlations and concordance among the replicates (fig. S8A). We identified 5684 and 10,385 LRF binding sites in HSPC-derived proerythroblasts and HUDEP-2 cells, respectively (fig. S8B). The most enriched motif identified in either cell type was consistent with that previously identified in vitro using CAST (cyclic amplification and selection of targets) analysis (16), confirming antibody specificity (figs. S9 and S10). Genes differentially expressed in control and ZBTB7A KO cells were significantly enriched for LRF binding sites (Fisher's exact test, P < 1.6 × 10–5 and P < 8.3 × 10–13 for undifferentiated and differentiated conditions, respectively). It is also notable that LRF occupancy sites differ from those of the known γ-globin repressors SOX6 and BCL11A (17) (fig. S8C).

In support of a direct role of LRF at the β-globin cluster, we observed several significant LRF-ChIP binding signals at adult (HBB) and fetal (HBG1 and HBG2) globin genes and at upstream hypersensitivity (HS) sites within the locus control region (LCR) (Fig. 3 and supplementary text). To assess the local chromatin accessibility at the β-globin cluster in the presence or absence of LRF, we performed ATAC-seq [assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing (18)]. In control HUDEP-2 cells, the HBB gene and LCR HS sites, but not the γ-globin genes, exhibited ATAC-seq nucleosome-free signals (Fig. 3). In contrast, strong chromatin accessibility was evident at the γ-globin genes in ZBTB7AΔ/Δ cells before differentiation, and the signal was amplified upon differentiation. Strikingly, differential enrichment of ATAC signals in ZBTB7AΔ/Δ cells was evident only at the γ-globin genes (Fig. 3) but not at the HBB gene or HS sites, indicating that chromatin in the latter is accessible regardless of ZBTB7A genotype. Thus, although LRF binds to the HBB gene and HS sites as well as to the γ-globin genes, LRF depletion specifically opens chromatin at the γ-globin genes.

Fig. 3. LRF occupies the γ-globin gene and maintains local chromatin compaction.

LRF ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq signals at the β-globin cluster (HUDEP-2 cells) are shown, along with ChIP-seq enrichment for GATA1, KLF1, and TAL1 (25). Regions showing statistically significant ATAC-seq differences between LRF KO and wild-type HUDEP-2 cells are depicted in red. Because of high sequence similarity of HBG1 and HBG2, we analyzed LRFoccupancy sites at the γ-globin locus using two different mapping methods: one mapping all mappable fragments (“LRF all”) and the other mapping only uniquely mappable fragments (“LRF uniquely mapped”). In the “LRF all” track, fragments mappable to either HBG1 or HBG2 were randomly distributed between both genes (marked by asterisks).

To identify a repressor complex interacting with LRF in an unbiased fashion, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen with the human LRF-BTB domain as bait. A total of 360 positive clones were processed out of 52.1 million potential binding events. LRF-interacting proteins with high confidence included four ZBTB proteins, three NuRD/CHD family proteins, and two chromatin remodelers (fig. S11, A and B). Given their abundance in erythroid cells (fig. S12A) and their potential repressor function, we focused on three factors (GATAD2B, CHD3, and CHD8) for further validation. Interactions of LRF with each were validated by immunoprecipitation (fig. S12B). Because NuRD complex components are implicated in globin switching (17, 19, 20), we examined the LRF-GATAD2B interaction in more detail. Immunoprecipitation of human proerythroblast lysates with an antibody to LRF pulled down GATAD2B and other NuRD complex components (Fig. 4A). The interactions were also validated in mouse erythroid cells (fig. S10C). Although BCL11A reportedly interacts with NuRD components (21, 22), we did not detect BCL11A in the NuRD complexes containing LRF in either human or mouse erythroid cells (Fig. 4A and fig. S12C). For reciprocal validation, we performed immunoprecipitation in human erythroid cell lysates with antibodies to GATAD2B or MTA2; as expected, both antibodies pulled down LRF (Fig. 4B). BCL11A was readily detected in MTA2-containing protein complexes, as reported (22). Consistent with our findings, LRF was not identified as a BCL11A-interacting protein in proteomic affinity screens in erythroid cells (21, 22).

Fig. 4. LRF and BCL11A silence γ-globin expression through distinct mechanisms.

(A) Immunoprecipitation with antibody to LRF confirmed LRF-GATAD2B interaction in HSPC-derived erythroblasts. BCL11A was not detected in the LRF-containing NuRD complex. IP-sup denotes supernatant after immunoprecipitation (unbound fraction). (B) Reciprocal validation using antibodies to GATAD2B or MTA2. (C) Representative HPLC profiles of control (HUDEP-2_Cas9), ZBTB7A KO, BCL11A KO, and ZBTB7A/BCL11A DKO (clones 5 and 18) HUDEP-2 cells. (D) Bar graphs show proportions of HbF relative to adult globin (HbA0). Means of two independent samples per clone are shown. Error bars denote SD.

Finally, to determine whether LRF and BCL11A suppress γ-globin expression via distinct mechanisms, we established ZBTB7A/BCL11A double-knockout (DKO) HUDEP-2 cells (fig. S12D) and compared HbF in these cells to that in ZBTB7A or BCL11A single-KO HUDEP-2 cells. DKO cells exhibited a significantly greater fetal/adult β-globin ratio than did either ZBTB7A or BCL11A single-KO cells (fig. S12, E and F). The HbF levels of DKO cells were at 91 to 94% of total Hb (Fig. 4, C and D). These data suggest that LRF and BCL11A represent a primary fetal globin repressive activity in adult erythroid cells (fig. S13).

Our results show that LRF is a potent repressor of embryonic/fetal β-like globin expression in adult erythroid cells. We postulate that LRF depletion opens local chromatin at the γ-globin genes, thereby enabling erythroid transcriptional activators to induce γ-globin expression. Furthermore, we propose that LRF silences γ-globin expression independently of BCL11A, as implied by our observations that (i) LRF inactivation in mice specifically reactivates Hbb-bh1, but not Hbb-y, expression, whereas BCL11A depletion induces both of these embryonic globins (13); (ii) LRF directly binds to the HBG1 gene, whereas BCL11A reportedly targets intergenic region(s), the LCR, and sequences between HBG1 and HBD (17, 23); (iii) the LRF-NuRD complex in adult erythroid cells lacks BCL11A; and (iv) ZBTB7A/BCL11A DKO HUDEP-2 cells exhibit significantly greater γ-globin expression than do either ZBTB7A or BCL11A single-KO cells.

Our work suggests that the two NuRD-associated pathways, in which LRF and BCL11A are respectively involved, are responsible for turning off fetal globin expression in order to switch over to adult globin. These findings may enable the development of therapies to turn on fetal globin expression in individuals with human hemoglobinopathies displaying defective adult globin gene expression.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank P. Jarolim, D. Dorfman, and other members of BWH Hematology laboratory for help on HPLC analysis; J. Hughes, J. Eglinton, J. Sharp, C. Babbs, K. di Gleria, D. Chen, and P. Schupp for technical support and assistance; E. Lamar for critical reading of the manuscript; and S-U. Lee, H. Yi, Y. Ishikawa and other members of the Maeda lab for help and advice. Supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Predoctoral National Research Service Award for M.D./Ph.D. Fellowship F30DK103359-01A1 (M.C.C.), NIDDK Career Development Award K08DK093705 and Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Innovations in Clinical Research Award 2013137 (D.E.B.), NIH grants P01HL032262 and P30DK049216 (Center of Excellence in Molecular Hematology) (S.H.O.), NIH grant 5K25AG037596 and Ellison Medical Foundation grant AG-NS-0965-12 (P.V.K.), and NIH grants R01 AI084905 and R56 DK105001 and an American Society of Hematology Bridge Program grant (T. Maeda). All reagents described in this manuscript (mouse models, plasmids) are available to the scientific community upon request. Sequencing data are available at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO accession number GSE74977). T. Masuda, M. Maeda, and T. Maeda are contributors to a patent application filed on behalf of Brigham and Women's Hospital related to therapeutic targeting of LRF/NuRD interaction.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencemag.org/content/351/6270/285/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S14

References (26-64)

REFERENCES

- 1.Stamatoyannopoulos G. Exp. Hematol. 2005;33:259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pleasants S. Nature. 2014;515:S2. doi: 10.1038/515S2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piel FB, Hay SI, Gupta S, Weatherall DJ, Williams TN. PLOS Med. 2013;10:e1001484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer DE, Kamran SC, Orkin SH. Blood. 2012;120:2945–2953. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-292078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SU, Maeda T. Immunol. Rev. 2012;247:107–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SU, et al. Blood. 2013;121:918–929. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-418103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.See supplementary materials on Science Online.

- 8.Kingsley PD, Malik J, Fantauzzo KA, Palis J. Blood. 2004;104:19–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baron MH, Isern J, Fraser ST. Blood. 2012;119:4828–4837. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-153486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chada K, Magram J, Costantini F. Nature. 1986;319:685–689. doi: 10.1038/319685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kingsley PD, et al. Blood. 2006;107:1665–1672. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterson KR, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:7593–7597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu J, et al. Science. 2011;334:993–996. doi: 10.1126/science.1211053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda T, et al. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:527–540. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurita R, et al. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e59890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maeda T, et al. Nature. 2005;433:278–285. doi: 10.1038/nature03203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu J, et al. Genes Dev. 2010;24:783–798. doi: 10.1101/gad.1897310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:1213–1218. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rupon JW, Wang SZ, Gaensler K, Lloyd J, Ginder GD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:6617–6622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509322103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amaya M, et al. Blood. 2013;121:3493–3501. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-466227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sankaran VG, et al. Science. 2008;322:1839–1842. doi: 10.1126/science.1165409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:6518–6523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303976110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sankaran VG, et al. Nature. 2009;460:1093–1097. doi: 10.1038/nature08243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan IT, et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:528–538. doi: 10.1172/JCI20476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su MY, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:8433–8444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.413260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.