Abstract

Of the handful of national studies tracking trends in adolescent substance use in the United States, only the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study collects data from 6th through 10th graders. The purpose of this study was to examine trends from 1998 to 2010 (four time points) in the prevalence of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use among 6th through 10th graders. Differences in trends by grade, gender, and race/ethnicity were examined for each substance use behavior, with a primary focus on trends for sixth and seventh graders. Overall, there were significant declines in tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use from 1998 to 2010. The declines were largest for the younger grades, which suggest promise for future declines among high school students as these cohorts age into high school.

Keywords: adolescent tobacco use, adolescent alcohol use, substance use trends, national prevalence of substance use

Substance Use Trends in U.S. Adolescents

There is evidence from analyses of repeated cross-sectional samples of high school students in the United States that the most commonly used substances in adolescence (tobacco and alcohol) have been in decline for at least a decade (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012). There are also indications that marijuana use has declined over the last decade, but the decline may have plateaued or even begun a reversal (Johnston et al., 2012). So far, none of these studies have tracked substance use in adolescents younger than the eighth grade. Thus, it remains unknown the extent to which trends among younger adolescents are similar to trends among high school-aged adolescents.

The Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), conducted biennially with nationally representative samples of 9th- through 12th-grade students, found that the prevalence of current smoking (smoked on at least 1 day in the past 30 days) significantly declined between 1997 and 2011 with all grades combined in analysis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012c). However, no significant changes occurred between 2009 and 2011. Similar findings were reported by the Monitoring the Future (MTF) survey, which is conducted annually with a nationally representative sample of 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students. Any use of cigarettes has declined for 8th graders from 45.7% in 1998 to 20.5% in 2008. Since 2008, the declines have slowed. In 2011, the prevalence of any cigarette use was 18.4%. For 10th graders, any cigarette use was 57.7% in 1998 and dropped to 31.7% in 2007. In 2011, it was 30.4%, a decline of just 1.3%. These results suggest that declines in smoking may be leveling off for 8th- through 12th-grade students (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012c; Johnston et al., 2012).

Declines in alcohol use also appear to have flattened. The YRBS found that lifetime alcohol use declined from 81.0% in 1999 to 70.8% in 2011, but not from 2009 (72.5%) to 2011 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012a). However, current binge drinking, defined as having five or more drinks of alcohol within a couple hours during the 30 days before the survey, declined from 33.4% in 1997 to 21.9% in 2011 as well as from 2009 (24.2%) to 2011. Marijuana use is of concern because data indicate that declines may be reversing. According to the YRBS, lifetime marijuana use and past month marijuana use decreased from 1999 to 2011 (47.2% to 39.9% for lifetime use; 26.7% to 23.1% for past month use) but increased from 2009 to 2011 (36.8% to 39.9% for lifetime use; 20.8% to 23.1% for past month use; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012b). The MTF survey has reported a gradual increase in marijuana use since 2007 (Johnston et al., 2012).

Demographic Differences in Trends

Historically, there has been a gender gap in the prevalence of various substances. As prevalence patterns change, it is possible the amount of change varies by gender. The MTF study has found that the prevalence of substance use generally moves in parallel for boys and girls with the gap widening when prevalence rates are higher (Johnston et al., 2012). However, there are some differences in gender by grade. For example, MTF found that for 8th-grade students, girls had higher rates of current alcohol use since 2002, but not before then. And among 10th graders, girls had similar rates as boys before 2005, but the gap has widened since then, with boys having higher rates of use (Johnston et al., 2012).

International studies of substance use trends have also found gender differences in alcohol use trends. Two studies using data from several countries, predominantly Western European countries, found that measures of alcohol use for 15-year-olds (e.g., monthly alcohol use, drunkenness) declined from 1998 to 2006, and the overall decline was greater among boys than girls. Alcohol use remained higher among boys than girls, but the gap between genders declined (Kuntsche et al., 2011; Simons-Morton et al., 2009).

In addition to gender differences, it is possible that trends differ by race/ethnicity. For example, the MTF study has found that marijuana use is increasing among African American students, closing the gap between Whites and African Americans (Johnston et al., 2012). Differences in trends by race/ethnicity or gender have been given less attention with YRBS data.

Current Study

To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined trends in substance use among the youngest adolescents (i.e., sixth- and seventh-grade students), yet it is important to do so for the following reasons. First, early onset of substance use is a marker of increased vulnerability to the negative consequences of substance use (Ellickson, Tucker, & Klein, 2001; Hingson, Heeren, & Winter, 2006; Lynskey et al., 2003) and thus, it is important to monitor the prevalence of substance use even if the majority of youth are not yet regular users. Second, substance use trends among young adolescents have important implications for older adolescents. If the declines among high school students are not mirrored among younger adolescents then this could indicate that the factors to which we attribute the declines (e.g., policy changes, social trends, community-based prevention efforts, school-based prevention efforts) may not be affecting younger adolescents to the same extent as high school students. A lack of a decline or an increase in substance use among younger adolescents could foretell a cohort effect that could reverse previous declines.

The purpose of the current study is to examine trends in adolescent tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use, among 6th- through 10th-grade students in the United States. This study uses four time points from the Health Behavior in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study, spanning 12 years. HBSC is the only nationally representative study to track substance use, among other health risk behaviors, among students as young as sixth grade. Trends in substance use were examined for differences by gender and race/ethnicity and a particular focus given to differences in trends across the range of grades.

Method

Sample and Procedure

The data for this study were part of the HBSC study from the following school years: 1997–1998, 2001–2002, 2005–2006, and 2009–2010. The HBSC study uses a repeated cross-sectional design and is administered every 4 years among a nationally representative sample of 6th-through 10th-grade students in the United States. The HBSC study is conducted in a manner to be compatible with the international administrations (among 11-, 13-, and 15-year-olds). Currently, the HBSC study is administered in 43 countries, primarily in Europe. Students were selected using a three-stage stratified clustered sampling design. The sampling frame consisted of U.S. public, catholic, and other private school students in Grades 6 through 10. The source of the sample frame for 1998 and 2002 was the Department of Education Common Core Data (CCD). In 2006 and 2010, Quality Education Data was used. The primary sampling unit was school districts, which were stratified based on nine census regions and grade level in school. From the primary sampling unit of school districts, schools were selected and then classes within schools using equal probability systematic sampling (similar to random sampling). School participation rates ranged from 58% to 73%. All students in a selected class were asked to participate in the study. Student participation rates ranged from 75% to 87%. Schools with minority students were oversampled to provide reliable estimates for African Americans and Hispanics. Further detail about the HBSC study and sampling methods has been described previously (Roberts et al., 2007). Data were collected using anonymous paper-based questionnaires distributed in classrooms. Youth assent and parental consent were obtained as required by the participating school districts. The Institutional Review Board at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development approved the study.

Measures

Due to low frequencies of frequent substance use, particularly among sixth- and seventh-grade students, all substance use measures were dichotomized into current, ever, or past year substance use compared with less frequent use.

Current tobacco use

Students were asked how often they smoke tobacco at present. Response options included, “I do not smoke,” “less than once a week,” “at least once a week, but not every day,” and “every day.” Those who reported they smoke “less than once a week” or more were categorized as currently using tobacco.

Current alcohol use

Students reported the frequency they currently drink beer, wine, liquor/spirits, and premixed drinks (such as Smirnoff Ice, Bacardi Breezer, and Mike’s Hard Lemonade). Response options were “every day,” “every week,” “every month,” “rarely,” and “never.” Those who reported drinking any alcoholic drink “every month,” or more frequently, were considered to be currently using alcohol.

Ever been drunk

Students responded to the question, “Have you ever had so much alcohol that you were really drunk?” Responses ranged from “no, never” to “10 times or more.” Students who reported having ever been really drunk once or more were considered to have ever been drunk.

Past year marijuana use

Students reported if they had used marijuana in the past 12 months. Response options ranged from “never” to “40 times or more.” Students who reported having used marijuana one or more times in the past year were categorized as having used marijuana in the past year. Marijuana use was not assessed for sixth-, seventh-, and eighth-grade students in 2002.

Demographic variables

Students reported their gender (male or female) and race/ethnicity (White, African American, Hispanic, Asian, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, or Native American). Due to small numbers of some race/ethnicity groups, the variable was reduced to four categories (White, African American, Hispanic, and Other race/ethnicity).

Analyses

Prevalence estimates were calculated for each of the substances at the four time points by grade. Logistic regressions were used to determine significant trends across the four time points. First, we tested for the overall shape of the trend as linear or quadratic; an interaction term for time was included to test for significant quadratic trends. After determining the shape of the trend, we tested for differences in trends by grade, gender, and race/ethnicity by including interaction terms for each demographic variable with time. Significance was set at p < .01 for all interactions due to the large sample size. If a significant interaction was found, it was explored by using subgroup analysis (the domain statement in SAS). Significant differences between groups were determined using non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals (CI). All statistical analyses were done with SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, 2010) and incorporated the complex sampling design (stratification and clustering) and sampling weights to provide nationally representative estimates.

Results

Table 1 presents the sample composition at each of the four survey assessments. As noted in Table 1, the sample size ranged from 15,686 in 1998 to 9,227 in 2006. As the HBSC study uses a repeated cross-sectional design, the difference in sample size across survey administrations does not reflect a loss to follow-up or increased non-participation rate. Rather, it is a by-product of changes in data collection strategy during this time frame. There were slightly more females than males at each survey administration, except for in 2010. A majority of the sample reported their race/ethnicity as White at all four time points and an increasing proportion of students reported their race/ethnicity as Hispanic. Table 1 also presents the prevalence of each substance use behavior by grade, gender, and race/ethnicity for each year. The overall rate of tobacco use declined from 22.1% in 1998 to 9.7% in 2010. Declines were also seen in current alcohol use, from 26.0% in 1998 to 12.4% in 2010; ever been drunk, from 28.7% in 1998 to 15.8% in 2010; and in past year marijuana use, from 22.1% in 1998 to 12.0% in 2010.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Substance Use and Demographic Characteristics by Year.

| Total

|

Current tobacco use

|

Current alcohol use

|

Ever been drunk

|

Past year marijuana use

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 98 | 02 | 06 | 10 | 98 | 02 | 06 | 10 | 98 | 02 | 06 | 10 | 98 | 02 | 06 | 10 | 98 | 02a | 06 | 10 | |

| Total | 22.1 | 14.8 | 10.3 | 9.7 | 26.0 | 17.0 | 17.7 | 12.4 | 28.7 | 22.6 | 20.1 | 15.8 | 22.1 | 29.8 | 13.5 | 12.0 | ||||

| Grade | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6th | 20.0 | 20.5 | 19.4 | 18.5 | 11.5 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 2.4 | 13.6 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 4.4 | 12.1 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 2.7 | 7.6 | — | 2.7 | 2.0 |

| 7th | 20.1 | 20.9 | 19.5 | 19.6 | 15.0 | 9.8 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 15.7 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 5.6 | 16.9 | 12.1 | 9.2 | 6.0 | 11.3 | — | 5.2 | 3.8 |

| 8th | 19.5 | 20.4 | 19.1 | 19.7 | 23.6 | 15.1 | 10.3 | 7.7 | 27.3 | 14.8 | 14.9 | 9.8 | 26.9 | 19.5 | 18.5 | 11.6 | 22.6 | — | 11.7 | 8.2 |

| 9th | 21.4 | 20.2 | 22.0 | 21.9 | 29.2 | 21.1 | 12.8 | 14.8 | 35.0 | 23.8 | 24.7 | 17.7 | 40.8 | 34.1 | 26.9 | 24.2 | 33.1 | 27.0 | 18.6 | 21.1 |

| 10th | 19.0 | 17.9 | 19.9 | 20.2 | 30.4 | 24.3 | 18.2 | 16.6 | 37.5 | 31.5 | 31.2 | 22.7 | 45.2 | 43.3 | 37.8 | 31.5 | 34.6 | 32.6 | 28.2 | 22.6 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Female | 53.3 | 51.9 | 50.3 | 47.9 | 21.3 | 12.9 | 9.7 | 8.6 | 24.1 | 14.9 | 16.5 | 11.2 | 27.0 | 21.4 | 19.7 | 15.4 | 19.7 | 26.2 | 12.6 | 10.3 |

| Male | 46.6 | 48.1 | 49.7 | 52.1 | 23.0 | 16.9 | 10.9 | 10.7 | 28.3 | 19.3 | 18.9 | 13.5 | 30.6 | 24.0 | 20.6 | 16.2 | 24.9 | 33.7 | 14.5 | 13.6 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||||||

| White | 64.0 | 62.9 | 51.2 | 52.5 | 22.8 | 14.9 | 10.2 | 9.3 | 25.8 | 17.7 | 19.4 | 11.9 | 29.5 | 23.3 | 20.8 | 15.1 | 21.5 | 29.7 | 13.0 | 9.5 |

| African American | 16.5 | 16.5 | 18.8 | 17.5 | 19.0 | 13.1 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 27.3 | 14.1 | 12.4 | 12.9 | 23.2 | 17.7 | 14.4 | 15.1 | 22.9 | 24.3 | 13.1 | 15.6 |

| Hispanic | 12.6 | 12.8 | 20.0 | 20.5 | 23.0 | 15.7 | 11.2 | 11.4 | 28.3 | 18.9 | 18.1 | 13.6 | 34.0 | 25.9 | 23.1 | 18.8 | 27.2 | 36.1 | 15.5 | 16.1 |

| Other | 6.9 | 7.9 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 20.4 | 15.7 | 9.4 | 8.6 | 20.9 | 14.1 | 20.1 | 12.3 | 24.0 | 21.4 | 22.5 | 14.9 | 17.1 | 30.5 | 14.4 | 11.7 |

Note. Percentages are weighted. N for 1998 = 15,686; N for 2002 = 14,818; N for 2006 = 9,227; N for 2010 = 10,925.

Marijuana use was not assessed for 6th-, 7th-, and 8th-grade students in 2002.

Trends in Tobacco Use

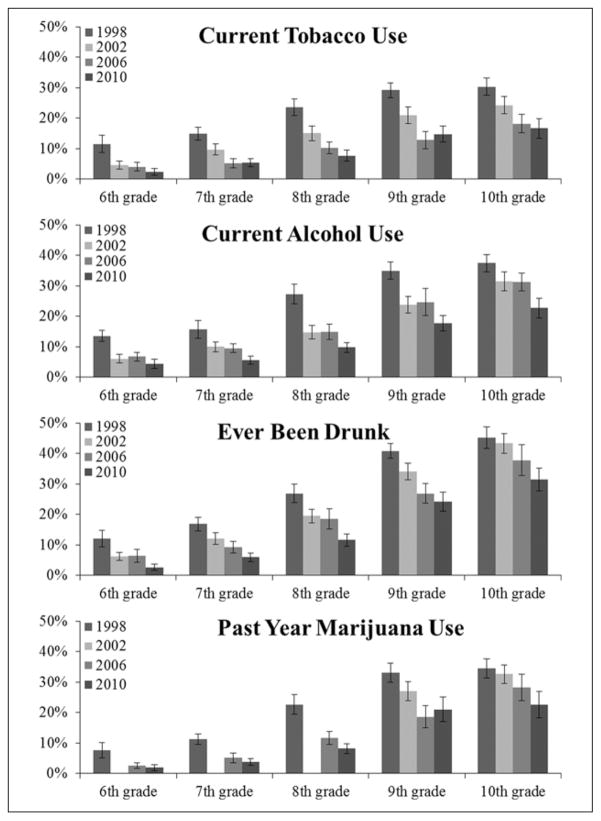

An overall test of the shape of the trend in tobacco use had a significant quadratic parameter (linear b = −85, p < .001; quadratic b = .10, p < .001). Further subgroup analysis indicated that this trend was limited to the ninth grade and all other grades had significant linear declines without a quadratic form. A plot of the trend in tobacco use by grade, shown in Figure 1, indicates that for ninth-grade students, the linear declines of the first three time points flatten out between the last two time points.

Figure 1.

Trends in substance use for 6th through 10th grade from 1998 to 2010.

Note. Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals for prevalence rates. Past year marijuana use was not assessed for sixth-, seventh-, and eighth-grade students in 2002.

There were no significant differences in the overall trend in tobacco use by gender or race/ethnicity. There was a significant interaction by grade, Wald χ2 = 13.7 (3), p < .01. Further subgroup analysis by grade indicated that although there were significant declines in tobacco use for all grades, the declines were significantly greater in 6th grade when compared with 10th grade. Table 2 presents the regression parameter (logit) for linear declines for each of the five grades. (For ease of comparison across grades, the linear beta parameter is presented for the ninth grade despite finding a significant quadratic form.) The negative beta parameter for the 6th grade (b = −.56; 95% CI = [−.74, −.39]) indicates a significantly steeper decline in tobacco use compared with the 10th grade (b = −.27; 95% CI = [−.36, −.19]). Put another way, the relative decline in tobacco use from 1998 to 2010 was 79% among 6th graders but almost half that (45%) for 10th graders. No other differences among the grades were significant, but the tendency was for the declines to be less steep (i.e., parameter closer to zero) with increasing grade in school. The prevalence for tobacco use by grade for each assessment year is shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Prevalence and Trends in Substance Use by Grade.

| Current tobacco use

|

Current alcohol use

|

Ever been drunk

|

Past year marijuana use

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (95% CI) | % decline | b (95% CI) | % decline | b (95% CI) | % decline | b (95% CI) | % decline | |

| 6th Grade | −.56 [−.74, −.39]a | 79 | −.39 [−.51,−.28]a | 68 | −.46 [−.61, −.31]a | 78 | −.50 [−.69, −.30]a | 74 |

| 7th Grade | −.43 [−.54, −.32] | 64 | −.35 [−.45, −.25] | 64 | −.38 [−.46, −.29] | 65 | −.40 [−.51, −.29]b | 66 |

| 8th Grade | −.45 [−.54, −.36] | 68 | −.39 [−.47, −.31] | 64 | −.31 [−.39, −.23] | 57 | −.40 [−.49, −.31] | 64 |

| 9th Grade | −.33 [−.42, −.25] | 49 | −.28 [−.35, −.21] | 49 | −.27 [−.33, −.21] | 41 | −.24 [−.33, −.14] | 36 |

| 10th Grade | −.27 [−.36, −.19]a | 45 | −.22 [−.28, −.15]a | 39 | −.20 [−.27, −.13]a | 30 | −.20 [−.28, −.11]a,b | 35 |

Note. All logits are significant at p < .001; % decline is the percent relative decline within grade from 1998 to 2010. Superscripts are significantly different from each other, p < .05.

Trends in Current Alcohol Use and Ever Been Drunk

There were overall linear declines for current alcohol use and having ever been really drunk from 1998 to 2010 (current alcohol use, b = −.28, p < .001; ever been drunk, b = −.25, p < .001). There were no significant differences in these trends by gender or race/ethnicity. There were significant interactions by grade (current alcohol use, Wald χ2 = 17.8 (3), p < .001; ever been drunk, Wald χ2 = 22.4 (3), p < .001). Further subgroup analysis by grade indicated that although there were significant declines in current alcohol use and having ever been drunk for all grades, the declines were significantly steeper in 6th grade as compared with 10th grade (Table 2). For example, the prevalence of current alcohol use declined 68% from 1998 to 2010 for 6th graders but only 39% for 10th graders. Similarly, the prevalence of ever been drunk declined 78% for sixth graders during the study time period but only 30% for 10th graders. The prevalence for alcohol use by grade for each year of assessment is shown in Figure 1. As was the case for tobacco use, the only statistically significant difference in trends by grade was between 6th and 10th graders. However, the tendency was for the declines to be less steep with increasing grade in school.

Trends in Past Year Marijuana Use

There were overall linear declines for past year marijuana use from 1998 to 2010 (b = −.28, p < .001). There were no significant differences in this trend by gender. There was a significant interaction by race/ethnicity (Wald χ2 = 11.6 (3), p < .01) and grade (Wald χ2 = 21.5 (3), p < .001). Subgroup analysis by race/ethnicity indicated significant declines in all four groups, but the declines were significantly steeper for Whites and Hispanics compared with either African Americans or those of other race/ethnicity, as indicated by non-overlapping CIs for beta coefficients. Whites had relative declines of 56% in past year marijuana use and Hispanics had declines of 41%, whereas African Americans and those reporting some other race/ethnicity had declines of 32% (data not shown).

The significant interaction by grade followed a similar pattern seen with tobacco and alcohol use. There were significant linear declines for all grades but the declines were significantly steeper in 6th and 7th grade as compared with 10th grade (Table 2). To illustrate this, the prevalence of past year marijuana use declined 74% from 1998 to 2010 for 6th graders and 66% for 7th graders, but only 35% for 10th graders. The prevalence for past year marijuana use by grade for each survey year is shown in Figure 1.

Discussion

This study examined trends in the prevalence of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use among 6th through 10th grade students from 1998 to 2010. To our knowledge, this is the first nationally representative study to examine trends in substance use among youth as young as sixth and seventh grade. For all grades, the use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana significantly decreased between 1998 and 2010 and declines were the largest in the youngest grades, particularly sixth grade.

The declines in tobacco use are consistent with trends found in the YRBS and MTF (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012c; Johnston et al., 2012). The significant quadratic trend among ninth graders may reflect a slowing of declines among older students, which is suggested by recent data from the YRBS and MTF (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012c; Johnston et al., 2012). The trends in alcohol use are also consistent with other reports of domestic trends. We anticipated there might be differences in trends by gender based on European data, which showed a pattern of gender convergence as the prevalence of alcohol use among boys declined faster than girls (Kuntsche et al., 2011; Simons-Morton et al., 2009). The current study found no significant gender differences in trends in alcohol use, or any other substance. Unlike the MTF study, which found an increase in marijuana use since 2007 (Johnston et al., 2012), the current study found significant linear declines in marijuana use for all grades. However, the declines were not as steep among African Americans and those of other race/ethnicity.

The significant declines across substances and grade level suggest a secular trend toward less substance use. Over the past decade and a half, there have been increases in the price of cigarettes partly due to tax increases, a reduction in cigarette advertising due to the Master Settlement Agreement, a national antismoking advertising campaign, and the enactment of state and regional bans on smoking in public places (Lantz et al., 2000). These factors combine to provide significant public attention to the issue of tobacco use, especially among youth. As this attention has faded in recent years, there has been a slowing of the increase in perceived risk and disapproval of smoking among adolescents (Johnston et al., 2012).

The general decline in alcohol use in this study and other domestic reports (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012a; Johnston et al., 2012) is consistent with declines in adolescent alcohol use across Western Europe and other developed countries (Hibell et al., 2012; Kuntsche et al., 2011; Simons-Morton et al., 2009). In the United States and Western Europe, as compared with Eastern Europe, there has been an increase in policies that reduce youth access to alcohol and alcohol advertising (Anderson & Baumberg, 2006; Rehm, Zatonksi, Taylor, & Anderson, 2011). Moreover, there have been improvements in programs to prevent adolescent alcohol use (Spoth, Greenberg, & Turrisi, 2008). These factors likely contribute to the decline in alcohol use.

Some have suggested that a decrease in the use of one substance (i.e., alcohol) leads to an increase in another (i.e., marijuana), as adolescents substitute one drug for another. However, other researchers have countered this idea noting there is little evidence for a “displacement effect” as the patterns of alcohol use and marijuana use have moved in parallel (Johnston et al., 2012). Our study reinforces the idea that both alcohol use and marijuana use can decline at the same time. In fact, the significantly greater declines in marijuana use among sixth and seventh grade students are promising, suggesting that there might be future declines among high school students as younger cohorts age into high school.

Strengths and Limitations

These findings are subject to several limitations. Despite the data spanning more than a decade, there were a limited number of time points available, which limits the detail of the trend results. Due to changes in the survey over the years, there were relatively few measures of substance use that were available at all four time points. In particular, it would have been ideal to have measures such as binge drinking in the past 30 days and marijuana use in the past 30 days. Due to the different time frames referenced for each substance, it is impossible to make direct comparisons across substances within this study. However, comparisons can be made with other studies that have used the same time frame in their measures. In addition, we would have liked for the measure of marijuana use to be included in all four assessments for the youngest grades included in the study. Despite the limitations noted, the trends reported in this study span more than a decade, with the most recent administrations in 2010. The HBSC study data is the only source of national trends in substance use for sixth and seventh grade students.

Conclusions

The study found substantial declines in adolescent substance use from 1998 to 2010, with few differences by race/ethnicity and no differences by gender. The declines in substance use among 8th to 10th graders are largely consistent with other reports of prevalence trends in the United States. The finding that declines in all substances were steepest for the youngest grades has not previously been reported and provides an encouraging outlook for future trends.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported in part by the intramural research program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Biographies

Ashley Brooks-Russell is a postdoctoral fellow at the Prevention Research Branch at NICHD. She received her PhD in health behavior from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her interests include adolescent health risk behavior, particularly in the areas of substance use and dating violence.

Tilda Farhat received her PhD in health behavior from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research focuses on the etiology and prevention of health-risk behaviors among adolescents and young adults, and on social and environmental influences on these behaviors.

Denise Haynie is a staff scientist at the Prevention Research Branch at NICHD. She has a doctorate in developmental psychology from the Catholic University of America. She conducts behavioral research, both observational and intervention evaluation, in adolescent health behaviors. Her primary interests are adolescent development, parent-child relationships, and risk behaviors.

Bruce Simons-Morton is Senior Investigator and Chief of the Prevention Research Branch at NICHD, where he directs a program of research on child and adolescent health behavior. His current research focuses on social influences on adolescent health and problem behavior and the causes and prevention of motor vehicles crashes among novice young drivers.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Anderson P, Baumberg B. Alcohol in Europe: A public health perspective. London, England: Institute of Alcohol Studies; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance: United States. Atlanta, GA: Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology and Laboratory Services; 2011. Rep. No. 61 [No. 4] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in the Prevalence of Alcohol Use, National YRBS: 1991–2011 [On-line] 2012a Retrieved August 23, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/us_alcohol_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in the Prevalence of Marijuana, Cocaine, and Other Illegal Drug Use, National YRBS: 1991–2011 [On-line] 2012b Retrieved August 23, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/us_drug_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in the Prevalence of Tobacco Use, National YRBS: 1991–2011 [On-line] 2012c Retrieved August 23, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/pdf/us_tobacco_trend_yrbs.pdf.

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. High-risk behaviors associated with early smoking: Results from a 5-year follow-up. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28:465–473. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibell B, Guttormsson U, Ahlström S, Balakireva O, Bjarnason T, Kokkevi A, Kraus L. The 2011 ESPAD Report: Substance use among students in 36 European countries [On-line] 2012 Retrieved August 23, 2013, from http://www.espad.org/Uploads/ESPAD_reports/2011/The_2011_ESPAD_Report_FULL_2012_10_29.pdf.

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975–2011. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Kuntsche S, Knibbe R, Simons-Morton B, Farhat T, Hublet A, …Demetrovics Z. Cultural and gender convergence in adolescent drunkenness. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165:152–158. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PM, Jacobson PD, Warner KE, Wasserman J, Pollack HA, Berson J, Ahlstrom A. Investing in youth tobacco control: A review of smoking prevention and control strategies. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:47–63. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Slutske WS, Madden PAF, Nelson EC, …Martin NG. Escalation of drug use in early-onset cannabis users vs. co-twin controls. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:427–433. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Zatonksi W, Taylor B, Anderson P. Epidemiology and alcohol policy in Europe. Addiction. 2011;106:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, Currie C, Samdal O, Currie D, Smith R, Maes L. Measuring the health and health behaviours of adolescents through cross-national survey research: Recent developments in the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study. Journal of Public Health. 2007;15:179–186. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) (Version 9.3) [Computer software] Cary, NC: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Farhat T, ter Bogt TFM, Hublet A, Kuntsche E, Gabhainn SN, …Kokkevi A. Gender specific trends in alcohol use: Cross-cultural comparisons from 1998 to 2006 in 24 countries and regions. International Journal of Public Health. 2009;52:S199–S208. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-5411-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Greenberg M, Turrisi R. Preventive interventions addressing underage drinking: State of the evidence and steps toward public health impact. Pediatrics. 2008;121:S311–S336. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]