Abstract

Objective

To determine if differences in conventional care among users and nonusers distinct CAM therapies varies by age and ethnicity.

Methods

The 2002 National Health Interview Survey data with a supplemental section on CAM use were analyzed.

Results

The odds of reporting each level of conventional care were greater for CAM users than nonusers for each type of CAM. There is consistent evidence that associations between CAM and conventional care use differ by age but not ethnicity.

Conclusions

Individuals who use CAM are greater users of conventional care, although these associations hold primarily for young and middle-aged adults. Results suggest that, for most CAM users, these therapies are not being used in place of conventional health care.

Keywords: complementary medicine, conventional care, physician visits, age differences, health self management

The widespread use of complementary and alterative medicine (CAM) has stimulated considerable interest among health behavior researchers concerning the way individuals combine CAM with conventional medical care. It is well established that individuals who use CAM are greater users of conventional care than are non-CAM users.1-3 Recent estimates suggest that 70 to 90% of CAM users combine their CAM therapies with conventional medicine.4 Based on this evidence, investigators frequently conclude that most people who use CAM are combining it with conventional therapies as part of their overall approach to health self-management.3,5-8 However, this conclusion is based on broad measures reflecting “any use” of a diverse array of distinct CAM modalities over the past 12 months. It is not clear if the link between CAM and elevated conventional care use differs among distinct CAM modalities. Similarly, there is substantial reason to suspect that the CAM – conventional care link may differ across segments of the population, such as age or ethnic groups, yet this possibility remains underresearched.4 Recognizing that interest in the joint use of CAM and conventional care is fueled by concerns that some individuals may substitute CAM for conventional care to reduce health care costs9 and that potential negative interactive effects may occur among therapies, it is vital to document which CAM modalities are associated with greater or lesser conventional care use and who is most likely to combine CAM and conventional care.

CAM consists of a wide variety of modalities that likely have different associations with conventional care use. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, for example, recognizes 5 main categories: (1) alternative medicine systems (eg, acupuncture, homeopathy), (2) biologically based therapies (eg, herbs, special diets), (3) manipulative and body-based methods (eg, chiropractic, massage), (4) energy therapies (eg, Reiki, qi-gong ), and (5) mind-body interventions (eg, relaxation, tai-chi). The link between conventional care use with modalities within these groupings would likely differ. For example, acupuncture, homeopathy, and other types of alternative medical systems have therapies and philosophies that may be incompatible with conventional medicine.10 In contrast, use of biologically based therapies like vitamin and herb supplements may be more easily combined with conventional medicine because supplements look and act like medications, and they are amenable to scientific inquiry. Indeed, classic examples such as folic acid supplementation to prevent neural tube defects in infants11 or calcium and vitamin D supplementation to minimize osteoporosis among maturing women12 indicate that biologically based therapies can become an integral part of conventional health care. Similarly, developing evidence suggesting that supplements derived from Chinese red rice yeast are effective in controlling cholesterol,13,14 that folic acid may have beneficial effects in stroke prevention,15 or that plant estrogens such as those found in botanicals may help manage menopausal hot flashes16 suggests that biologically based therapies such as vitamin and herb supplements can be easily merged with conventional medical care.

There is substantial reason to believe that the link between CAM and conventional care use differs by age and ethnicity. Age-related differences in use have been documented across the major modalities of CAM.7,17 Lower base differences in CAM use among older adults relative to midlife adults as well as age-related differences in the extent to which poor health contributes to use of CAM18 suggest that the link between CAM and conventional care may be weaker for older adults than midlife adults. Similarly, base differences in the use of some CAM modalities by ethnicity, such as greater use of biologically based therapies by Asians than whites,17-19 create the opportunity for the CAM-conventional care link to differ by ethnicity. Indeed, recent evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) indicated substantial variation by ethnicity in the way adults combine use of CAM practitioners with their use of conventional medicine.4 The link between CAM and conventional care may also vary by age and ethnicity because of variation in economic resources. Older adults, as well as blacks and Latinos, experience greater economic hardship, which may further weaken the link between CAM and conventional care, as people may use CAM therapies in place of conventional care to stretch limited financial resources.9 Further, the association of CAM with conventional care may be weaker among members of minority groups because they have generally greater difficulty accessing conventional health care.20

The goal of this paper was to refine understanding of the CAM – conventional health care association. To accomplish this goal, we used data from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey with Alternative Health Supplement to determine if conventional care use is greater among users of recognized categories of CAM therapies relative to nonusers. We also determined if the CAM-conventional care association differs by age and ethnicity. Although several papers focused on age and ethnic differences in CAM use have been published using the NHIS,7,9,18,19,21-23 most have focused on describing age and ethnic differences in CAM use. This is the first paper to focus explicitly on the presumed link between CAM and conventional care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data for this paper come from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). The NHIS is a representative, population-based survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized US population, which has been conducted annually since 1957 by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Data are obtained through face-to-face interviews conducted by US Census Bureau personnel in English. The sampling plan for the NHIS follows a multistage area probability design. The final survey includes approximately 106,000 persons from about 43,000 households. The household response rate for the 2002 survey was 89.6%.

The NHIS includes 3 components in the Basic module: the Family Core, the Sample Adult Core, and the Sample Child Core. All adult members of a household are invited to complete the Family Core component, whereas a randomly selected (if more than one) adult family member is selected to complete the Sample Adult Core. In the 2002 NHIS, respondents for the Sample Adult Core also completed the Alternative Health Supplement. The data for this analysis were drawn from participant responses to questions in the Family Core, the Sample Adult Core, and the Alternative Health Supplement The Sample Adult Core of the 2002 NHIS was completed by 31,044 adults, and 30,785 (99.2%) completed the Alternative Health Supplement. Sampling weights allow this sample to represent the noninstitutionalized US population. For these analyses, respondents whose race/ethnicity was categorized as Native American or Other/Multiple Races were excluded due to small sample sizes.

Measures

Use of conventional medicine, the primary dependent variable, was measured by the question “During the past 12 months, how many times have you seen a doctor or other health care professional about your own health at a doctor's office, a clinic, or some other place? Do not include times you were hospitalized over night, visits to hospital emergency rooms, home visits, dental visits, or telephone calls.” Possible responses were none, 1, 2 – 3, 4 – 5, 6 – 7, 8 – 9, 10 – 12, 13 – 15, or 16 or more. Responses were converted to an ordered category reflecting none, 1 visit, 2 – 3 visits, 4 – 5 visits, 6 – 9 visits, and 10 or more.

The primary independent variables were any use of CAM and any use of specific categories of CAM. The NHIS asked respondents if they used 20 different unconventional modalities within the past year. Responses to these items were combined to create a dichotomous any CAM use variable, as well as dichotomous variables reflecting any use of 4 of the 5 CAM groupings recognized by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, including alternative medical systems (ie, any use of acu-puncture, ayurveda, homeopathy, or naturopathy in the past year), biologically based therapies (ie, any use of chelation therapy, folk medicine, herb use, diet-based therapy, or megavitamin therapy in the past year), manipulative and body-based methods (ie, any use of chiropractic and massage in the past year), and mind-body medicine (ie, any use of biofeedback, relaxation techniques such as meditation, hypnosis, movement therapies such as yoga, or healing rituals in the past year). NCCAM also recognizes energy therapies such as Qi Gong and Reiki. However, like earlier reports,17 we combined these modalities with mind-body medicine because questions about Qi Gong could not be separated from those about yoga and tai chi; and we felt it was inappropriate to have Reiki solely represent a class of therapy.

Race and ethnicity were operationalized categorically representing non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic. Age was operationalized continuously. Other covariates included gender, census region, and educational attainment (less than a high school diploma, a high school diploma or equivalent with or without some college or technical training, and a 4-year college degree or more). The number of chronic health conditions was categorized as 0, 1 – 2, 3 – 4, and 5 or more.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) callable SUDAAN software in order to account for the complex survey design (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC). The sample adult weight – final annual variable was used in order to produce population estimates. Descriptive statistics of past-year users and nonusers of CAM were generated for each of the demographic characteristics using PROC CROSSTAB. Because the proportional odds assumption could not be sufficiently tested using SUDAAN, a generalized logit model was employed to analyze the ordinal outcome, ie, number of conventional doctor visits in the past year. PROC MULTILOG was used to fit a generalized logit model comparing each of the response categories with the reference, ie, no doctor visits in the past year. The effects of CAM use, age, and the interaction of CAM use and age were examined, controlling for the effects of gender and ethnicity. Separate models were fit for any CAM use and each of the 4 major CAM modalities, ie, any use of alternative medical systems, any use of biologically based therapies, any use of manipulative and body-based therapies, and any use of mind-body therapies. The final set of models were fit controlling for gender, age, region, education, income, and number of health conditions. Estimates for the odds ratios of CAM use were calculated using the beta coefficients from each model. The delta method was used to calculate the variance estimates and the 95% confidence intervals for the odds ratios. For the models with significant age by CAM interactions, the odds ratios of CAM use and the 90% confidence intervals were plotted.

RESULTS

The NHIS sample represents a population in which 37.1% (95% CI: 36.3% - 37.9%) of adults report using some type of CAM in the year prior to the interview. Table 1 describes the sample, comparing those who report use of CAM in the past year with nonusers. There are significant ethnic differences in CAM use (P<0.0001), with 44.1% of Asians reporting use, compared to 29.3% of Hispanic respondents, 39.1% of whites, and 29.7% of blacks. There are several significant differences among categories of persons who use CAM, with the highest frequency being seen among females, those aged 45 to 64, individuals living outside the southern census region, the better educated, and those reporting several chronic conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Personal and Health Characteristics of Users and Nonusers of Any Complementary or Alternative Medicine (CAM) in the Past Year

| Total | CAM Users | CAM Nonusers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N | % | SE | N | % | SE | n | % | SE | P-value |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Black | 4,185 | 11.5 | 0.33 | 1,226 | 29.7 | 0.83 | 2,785 | 70.3 | 0.83 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 5,273 | 11.1 | 0.27 | 1,520 | 29.3 | 0.86 | 3,592 | 70.7 | 0.86 | |

| Asian | 902 | 3.6 | 0.17 | 384 | 44.1 | 2.04 | 470 | 55.9 | 2.04 | |

| White | 20,442 | 73.8 | 0.44 | 7,902 | 39.1 | 0.47 | 11,941 | 60.9 | 0.47 | |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female | 17,398 | 52.0 | 0.37 | 6,836 | 41.5 | 0.52 | 10,033 | 58.5 | 0.52 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 13,404 | 48.0 | 0.37 | 4,196 | 32.3 | 0.53 | 8,755 | 67.7 | 0.53 | |

| Age | ||||||||||

| < 45 | 15,571 | 52.4 | 0.43 | 5,666 | 37.3 | 0.50 | 9,455 | 62.7 | 0.50 | <0.0001 |

| 45-64 | 9,394 | 31.5 | 0.34 | 3,815 | 41.6 | 0.66 | 5,304 | 58.4 | 0.66 | |

| > 65 | 5,837 | 16.1 | 0.29 | 1,551 | 27.7 | 0.71 | 4,029 | 72.3 | 0.71 | |

| Region | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 5,664 | 19.4 | 0.34 | 2,055 | 38.1 | 0.70 | 3,359 | 61.9 | 0.70 | <0.0001 |

| Midwest | 7,084 | 24.5 | 0.48 | 2,709 | 38.7 | 0.84 | 4,201 | 61.3 | 0.84 | |

| South | 11,400 | 37.0 | 0.51 | 3,534 | 31.9 | 0.62 | 7,527 | 68.1 | 0.62 | |

| West | 6,654 | 19.2 | 0.37 | 2,734 | 44.0 | 0.94 | 3,701 | 56.0 | 0.94 | |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Less than HS | 5,876 | 16.6 | 0.30 | 1,267 | 22.2 | 0.75 | 4,434 | 77.8 | 0.75 | <0.0001 |

| HS, GED, Some College | 17,479 | 58.9 | 0.39 | 6,173 | 36.1 | 0.46 | 10,836 | 63.9 | 0.46 | |

| College Graduate | 7,057 | 24.5 | 0.38 | 3,537 | 50.0 | 0.72 | 3,334 | 50.0 | 0.72 | |

| Income | ||||||||||

| < $20,000 | 7,716 | 19.4 | 0.34 | 2,333 | 30.6 | 0.77 | 5,165 | 69.4 | 0.77 | <0.0001 |

| >= $20,000 | 21,082 | 80.6 | 0.34 | 8,242 | 39.5 | 0.44 | 12,292 | 60.5 | 0.44 | |

| Chronic Conditions | ||||||||||

| 0 | 9,386 | 31.4 | 0.35 | 2,352 | 26.2 | 0.61 | 6,616 | 73.8 | 0.61 | <0.0001 |

| 1-2 | 10,209 | 34.1 | 0.31 | 3,698 | 37.6 | 0.66 | 6,246 | 62.4 | 0.66 | |

| 3-4 | 5,293 | 17.1 | 0.25 | 2,222 | 43.5 | 0.83 | 2,954 | 56.5 | 0.83 | |

| 5+ | 5,790 | 17.4 | 0.27 | 2,735 | 49.0 | 0.77 | 2,921 | 51.0 | 0.77 | |

Note.

Estimates obtained from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey.

Ns may not sum because of missing data.

Any CAM use and use of each major type of CAM is associated with incrementally increased odds of reporting greater use of conventional care (Table 2). For example, odds ratios illustrating differences in conventional care visits between CAM users and nonusers increased from 1.27 for the model predicting 1 versus no conventional care visits, to 1.80 and 2.92 for the models predicting 4 – 5 and 10 or more visits, respectively. The incremental effect of CAM use across levels of conventional care is particularly clear for use of manipulative and body-based methods where the estimated odds ratios increase across the categories of the outcome, and there is little overlap among several of the 95% confidence intervals. For example, the 95% confidence intervals for the 1 visit, 4-5 visits, and 10+ visits are 1.29 – 1.88, 2.44 – 3.49, and 4.95 – 7.03 respectively.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios From Simplea Ordered Logistic Regression Models Predicting Level of Conventional Medical Care Use by Use of Complementary Medicineb and Age

| 1 Visit (None) OR | 2-3 Visits (None) OR | 4-5 Visits (None) OR | 6-9 Visits (None) OR | 10+ Visits (None) OR | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Use of Complementary Medicine (CM) | ||||||

| CM | 1.27 (1.14-1.42) | 1.58 (1.43-1.74) | 1.80 (1.61-2.01) | 2.27 (2.02-2.55) | 2.92 (2.61-3.27) | <0.0001 |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 1.02 (1.02-1.02) | 1.04 (1.03-1.04) | 1.04 (1.04-1.05) | 1.04 (1.04-1.04) | <0.0001 |

| Age*CM | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-0.99) | 0.99 (0.98-0.99) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | <0.0001 |

| Any Use of Alternative Medicine System (AMS) | ||||||

| AMS | 1.26 (0.88-1.78) | 1.46 (1.06-2.02) | 1.90 (1.38-2.61) | 2.41 (1.75-3.33) | 3.78 (2.74-5.22) | <0.0001 |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 1.02 (1.01-1.02) | 1.03 (1.03-1.04) | 1.04 (1.04-1.04) | 1.03 (1.03-1.04) | <0.0001 |

| Age*AMS | 1.01 (0.99-1.04) | 1.00 (0.98-1.03) | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 1.01 (0.98-1.03) | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 0.5794 |

| Any Use of Biologically Based Therapy (BBT) | ||||||

| BBT | 1.19 (1.06-1.32) | 1.34 (1.21-1.49) | 1.47 (1.31-1.66) | 1.57 (1.37-1.79) | 1.80 (1.60-2.02) | <0.0001 |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 1.02 (1.02-1.02) | 1.04 (1.03-1.04) | 1.04 (1.04-1.04) | 1.04 (1.03-1.04) | <0.0001 |

| Age*BBT | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.0002 |

| Any Use of Manipulative or Body-based Methods (MBM) | ||||||

| MBM | 1.56 (1.29-1.88) | 2.42 (2.04-2.88) | 2.92 (2.44-3.49) | 3.86 (3.20-4.67) | 5.90 (4.95-7.03) | <0.0001 |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 1.02 (1.01-1.02) | 1.04 (1.03-1.04) | 1.04 (1.04-1.04) | 1.04 (1.03-1.04) | <0.0001 |

| Age*MBM | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.97-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.0384 |

| Any Use of Mind-Body-Intervention (MBI) | ||||||

| MBI | 1.30 (1.14-1.5) | 1.57 (1.38-1.77) | 1.74 (1.52-2.00) | 2.16 (1.86-2.51) | 2.64 (2.32-3.00) | <0.0001 |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 1.02 (1.02-1.02) | 1.04 (1.03-1.04) | 1.04 (1.04-1.05) | 1.04 (1.03-1.04) | <0.0001 |

| Age*MBI | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.0138 |

Note.

Models control for the effects of gender and ethnicity.

Each model examines one type of complementary medicine use.

However, it is also clear that the strength of the CAM – conventional care association differs across the major types of CAM (Table 2). Whereas the association between use of biologically based therapies with conventional care is modest (odds ratios ranging from 1.19 to 1.80), the association of manipulative and body-based methods with conventional care is consistent and strong (odds ratios ranging from 1.56 to 5.90). Likewise, there are notable differences in effect sizes across the types of CAM modalities within each category of the outcomes. At every level of the outcome, manipulative and body-based methods has the strongest association with conventional care use. For example, although the odds of reporting 10 or more visits as opposed to no visits are greater for users of each type of CAM, the odds ratios range from modest (1.80 for users of biologically based therapies) to medium (2.74 for users of alternative medicine systems) to large (5.90 for users of manipulative and body-based methods).

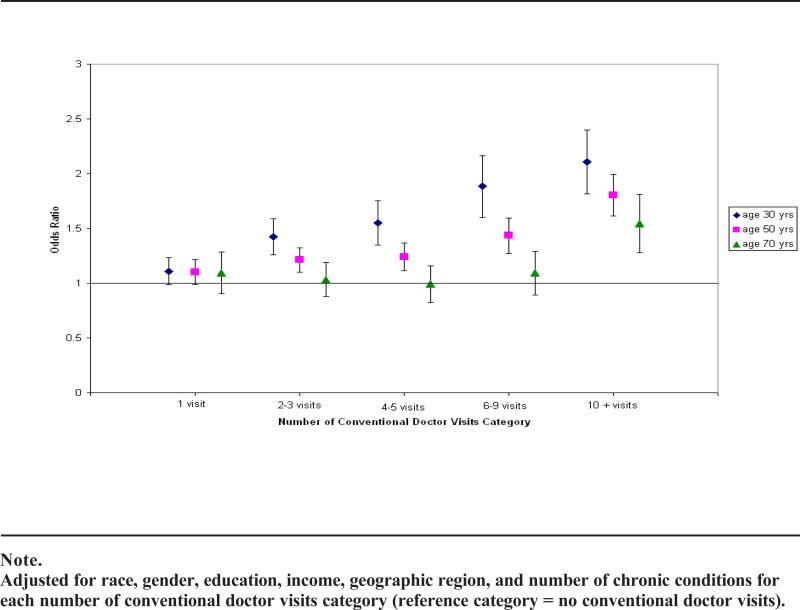

With the exception of alternative medicine systems, the association between use of each type of CAM and use of conventional care consistently differs by age (Table 2). Several of these interaction effects remain after adjusting for important covariates (Table 3), although the p-values are attenuated. Figures 1 through 4 plot estimated odds ratios for CAM users relative to nonusers for a 30-, 50-, and 70-year-old, respectively, to illustrate each of the observed interaction effects. These estimates were calculated from the ordered logistic regression models controlling for gender, education, region, household earnings, and number of chronic conditions. Figure 1 illustrates the age-related differences in the effect of any CAM use on number of conventional care visits. Regardless of age, the odds of reporting one conventional care visit relative to no visits do not differ among users and nonusers of CAM. Conversely, regardless of age, the odds of reporting 10 or more conventional care visits are greater for CAM users than nonusers. At the intermediate levels of conventional care, the CAM-conventional care association is age related. Among 70-year-old adults, there is no difference among CAM users and nonusers in the the odds of reporting 2-3, 4-6, or 6-9 visits relative to no visits. By contrast, among 30- and 50-year-old adults, the odds of reporting these levels of care are greater for CAM users than nonusers. Further, there is no overlap in the 95% confidence intervals for 30- and 70-year-olds within each category indicating that the effect of CAM on 2-3, 4-5, and 6-9 conventional care visits is greater for young adults (ie, 30-year-olds) than older adults (ie, 70-year-olds).

Table 3.

Odds Ratios From Multivariatea Ordered Logistic Regression Models Predicting Level of Conventional Medical Care Use by Use of Complementary Medicineb and Age

| 1 Visit (None) OR | 2-3 Visits (None) OR | 4-5 Visits (None) OR | 6-9 Visits (None) OR | 10+ Visits (None) OR | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Use of Complementary Medicine (CM) | ||||||

| CM | 1.10 (0.98-1.24) | 1.26 (1.14-1.40) | 1.31 (1.16-1.47) | 1.53 (1.34-1.74) | 1.87 (1.66-2.12) | <0.0001 |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 1.01 (1.01-1.01) | 1.02 (1.02-1.03) | 1.02 (1.02-1.03) | 1.01 (1.01-1.01) | <0.0001 |

| Age*CM | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-0.99) | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.0002 |

| Any Use of Alternative Medicine System (AMS) | ||||||

| AMS | 1.09 (0.76-1.55) | 1.18 (0.84-1.65) | 1.41 (1.01-1.97) | 1.64 (1.15-2.34) | 2.41 (1.70-3.42) | <0.0001 |

| Age | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 1.02 (1.01-1.02) | 1.02 (1.01-1.02) | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | <0.0001 |

| Age*AMS | 1.01 (0.99-1.04) | 1.00 (0.97-1.02) | 1.00 (0.97-1.02) | 1.00 (0.98-1.03) | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 0.5447 |

| Any Use of Biologically Based Therapy (BBT) | ||||||

| BBT | 1.04 (0.93-1.17) | 1.07 (0.96-1.20) | 1.08 (0.95-1.23) | 1.04 (0.9-1.21) | 1.16 (1.01-1.32) | <0.0001 |

| Age | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 1.01 (1.01-1.01) | 1.02 (1.02-1.02) | 1.02 (1.01-1.02) | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 0.3359 |

| Age*BBT | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.0140 |

| Any Use of Manipulative or Body-based Methods (MBM) | ||||||

| MBM | 1.41 (1.16-1.71) | 2.08 (1.74-2.49) | 2.44 (2.02-2.94) | 3.15 (2.58-3.83) | 4.74 (3.92-5.72) | <0.0001 |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 1.02 (1.02-1.02) | 1.02 (1.02-1.02) | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | <0.0001 |

| Age*MBM | 1.00 (0.98-1.01) | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.97-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.01) | 0.0689 |

| Any Use of Mind-Body Intervention (MBI) | ||||||

| MBI | 1.11 (0.96-1.28) | 1.23 (1.07-1.40) | 1.20 (1.03-1.39) | 1.38 (1.17-1.62) | 1.54 (1.33-1.78) | <0.0001 |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | 1.01 (1.01-1.01) | 1.02 (1.02-1.02) | 1.02 (1.02-1.02) | 1.01 (1.00-1.01) | <0.0001 |

| Age*MBI | 0.99 (0.99-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | 0.0844 |

Note.

Models control for the effects of gender, ethnicity, education, geographic region, income (ie, > $20,000 yes/no), and number of chronic conditions.

Each model examines one type of complementary medicine use

Figure 1.

Odds Ratios and 90% Confidence Intervals for Any CAM Use from Adjusted Models

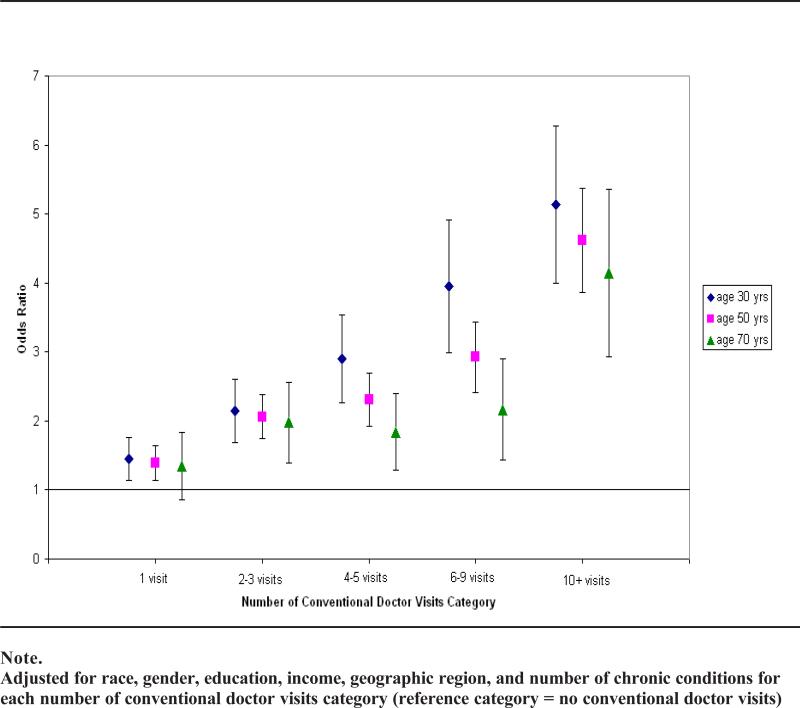

Figure 4.

Odds Ratios and 90% Confidence Intervals for Any Use of Mind-body Intervention from Adjusted Models

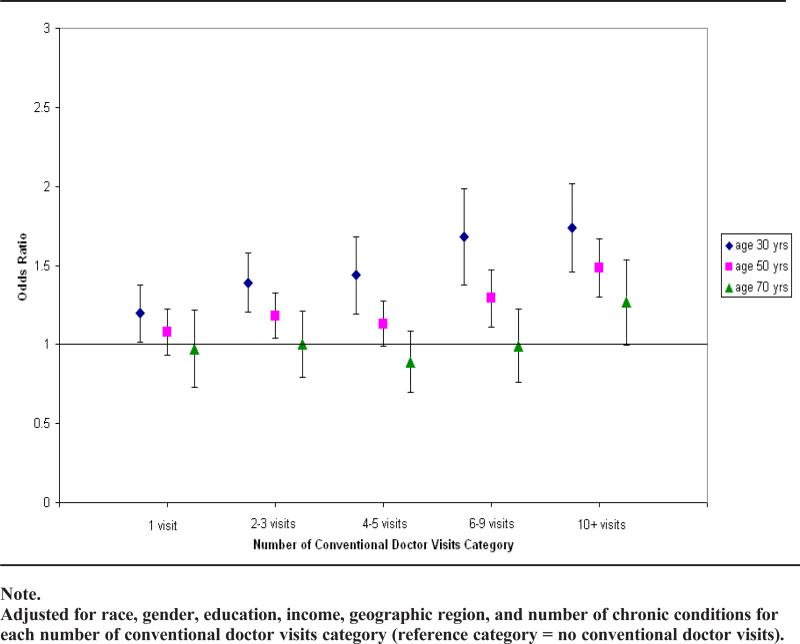

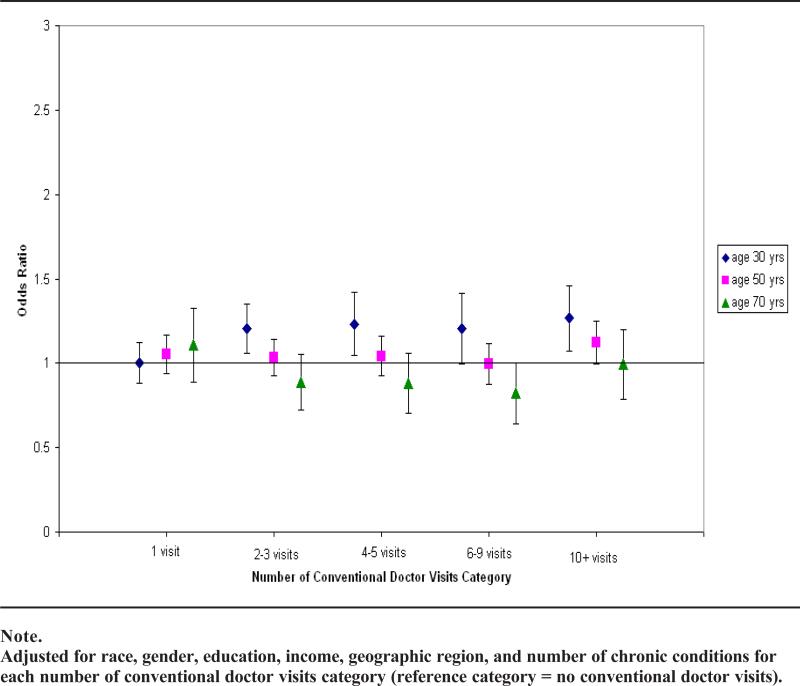

The remaining figures illustrate the other age-related differences in the CAM-conventional care association, and they highlight the importance of disaggregating the various types of CAM. Figure 2 indicates that, for young adults (ie, 30-year-olds), use of biologically based therapies is associated with greater odds of reporting 2 – 3, 4 – 5, and 10+ visits relative to no visits. However, among midlife and older adults (50- and 70-year-olds, respectively) there are no differences among biologically based therapy users and nonusers at any level of conventional care. Users of manipulative and body-based methods have greater odds than nonusers of reporting each level of conventional care use (Figure 3). Consistent with the trend-level (P < .10) age*CAM use interaction effect for this modality (Table 3), the Figure suggests that differences in conventional care use among manipulative and body-based methods users are greater for young adults than old adults. Finally, Figure 4 suggests that among older adults there are no differences between mind-body intervention users and nonusers in conventional care use. Among young adults, the odds of reporting each level of conventional care, except 1 visit, is greater for mind-body intervention users than nonusers. Among midlife adults, the odds of reporting 6 – 9 or 10+ visits were greater among mind-body intervention users than nonusers; otherwise, at lower levels of conventional care use, there are no differences between CAM users and nonusers.

Figure 2.

Odds Ratios and 90% Confidence Intervals for Any Use of Biologically-Based Therapies from Adjusted Models

Figure 3.

Odds Ratios and 90% Confidence Intervals for Any Use of Manipulative or Body-based Methods from Adjusted Models

Analyses yielded little evidence suggesting that the effect of CAM on conventional care use differed by ethnicity. Blacks did not generally differ from whites at each level of conventional care; however, the odds of reporting each level of conventional care was systematically lower for Hispanics and Asians relative to whites (Table 4). The effect of CAM use on 10 or more visits, relative to none, was weaker for blacks than whites; however, there was no other evidence indicating that the effect of any use of CAM on level of conventional care differed by ethnicity. Additional analyses (not shown) showed no evidence indicating that the link between specific types of CAM and conventional medical care use differed by ethnicity.

Table 4.

Odds Ratios From Ordered Logistic Regression Models Exploring Ethnic Differences in the Association Between Any Use of CAM and Level of Conventional Medical Care Use

| 1 Visit (None) OR | 2-3 Visits (None) OR | 4-5 Visits (None) OR | 6-9 Visits (None) OR | 10+ Visits (None) OR | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any CAM (CM) | 1.13 (0.99-1.29) | 1.34 (1.18-1.52) | 1.38 (1.20-1.58) | 1.64 (1.42-1.89) | 2.12 (1.84-2.45) | <0.0001 |

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | <0.0001 |

| Black | 0.97 (0.82-1.16) | 1.03 (0.87-1.22) | 1.10 (0.90-1.34) | 1.10 (0.89-1.37) | 1.06 (0.86-1.32) | |

| Hispanic | 0.74 (0.63-0.87) | 0.57 (0.49-0.67) | 0.63 (0.52-0.75) | 0.68 (0.54-0.85) | 0.73 (0.59-0.90) | |

| Asian | 0.79 (0.58-1.07) | 0.77 (0.57-1.04) | 0.86 (0.60-1.24) | 0.59 (0.35-0.99) | 0.57 (0.34-0.97) | |

| White*CM | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | 0.1280 |

| Black*CM | 0.97 (0.69-1.36) | 0.91 (0.67-1.23) | 0.92 (0.65-1.29) | 0.79 (0.54-1.14) | 0.62 (0.43-0.91) | |

| Hispanic*CM | 1.02 (0.79-1.32) | 1.14 (0.88-1.47) | 1.00 (0.75-1.34) | 0.83 (0.59-1.18) | 0.73 (0.52-1.01) | |

| Asian*CM | 1.00 (0.63-1.58) | 0.85 (0.53-1.36) | 0.82 (0.48-1.41) | 0.66 (0.34-1.29) | 0.90 (0.44-1.84) |

Note.

CM = Any CAM Use. Models control for gender, education, geographic region, income (ie, > $20,000 yes/no), and number of chronic conditions

DISCUSSION

There is substantial interest in the link between use of CAM and conventional health care use. Interest is driven by several factors including basic questions about how people use and integrate different health care options to self-manage their health, as well as accompanying concerns that some individuals may substitute alternative therapies for conventional care as a way of reducing individual health costs.9 Concerns over potential negative interactive effects from combining CAM therapies like herbs with conventional care also influence interest, particularly because most adults use some form of CAM, but they typically do not report use of these therapies to their conventional health care provider.1,2 Although studies consistently indicate that CAM users are greater users of conventional health care than are non-CAM users, it is unclear if this pattern holds across various types of CAM and is invariant across different segments of the population. This analysis was designed to determine if conventional care use is greater among users of different types of CAM therapies relative to nonusers and whether if the CAM-conventional care association differed by age and ethnicity. The results of this analysis make several contributions to the literature.

CAM users report greater use of conventional health care than nonusers report. Although previous research has documented that conventional care use is higher among CAM users than nonusers,1-3 this is one of the first studies to demonstrate that the pattern holds across 4 of the 5 major categories of therapies recognized by NCCAM. These results are consistent with recent results based on the MEPS data indicating that those seeking care from several distinct CAM practitioners are also greater consumers of conventional medical care.4 These results suggest that, for many adults, use of distinct types of unconventional therapies like acupuncture, herbal remedies, or massage is intended as a supplement rather than an alternative to conventional health care.1,3,4,24 Further, the results of this study are consistent with a growing body of evidence suggesting that CAM therapies are one component of adults’ overall approach to health and disease self-management,5,8,18 arguing that adults actively engage in a variety of healing practices to maintain health and well-being.

The results of this study also demonstrate that the link between use of CAM and conventional care is not simple. Most notably the association of use of biologically based therapies, manipulative and body-based methods, and mind-body interventions with conventional care all differ by age. Although the age interactions were attenuated after controlling for important covariates such as household income and number of chronic conditions, the interaction effects across the types of CAM were consistent: the effect of CAM use on level of conventional care was strongest and most consistent for young adults, less strong and consistent for middle-aged adults, and barely evident for older adults. Indeed, among 70-year-olds, differences between CAM users and nonusers were only discernable at higher levels of conventional care. These results are consistent with previous research highlighting cohort differences in age at first use of CAM25 and more recent evidence suggesting age-related, possibly cohort, differences in how adults use different forms of CAM in response to signs of poor health.18 The results of this study add to the literature by indicating possible cohort differences in how adults combine CAM and conventional care in their overall approach to health self-management. If these results are supported in future research, it would suggest that an increasing proportion of adults will combine CAM with conventional care.

There was no evidence in this study that the association between CAM and conventional care differed by ethnicity. The absence of ethnic differences in the strength of the CAM-conventional care association was unexpected in light of evidence indicating substantial variability in the overall levels of CAM use as well as use of specific modalities,18,19 as well as recent results from MEPS data indicating substantial interethnic variation in how use of practitioners for distinct types of CAM was associated with conventional care use.4 The diverging pattern of results between this study, which is based on the NHIS data, and the recent study based on the MEPS data is perplexing. One possible explanation is substantive; that is, whereas CAM use in the present study included use of CAM practitioners and self-directed use, the previous study focused on use of CAM practitioners. Perhaps the substantial amount of self-directed CAM use, as indicated by notably different estimates of “any use” (ie, roughly 2 – 6% in the MEPS versus 30-45% in the current study), dilutes ethnic variation in the linkages between CAM use and conventional care. A second explanation is more methodological in nature. The present study explicitly tested whether the parameter estimates linking CAM use to conventional care differed by ethnicity. By contrast, Xu and Farrell4 conducted ethnic-specific analyses and based conclusions on patterns of significant associations across the ethnic-specific models; they did not test whether the parameter estimates obtained from each model differed by ethnicity.

Clearly more research examining possible ethnic variation in the link between CAM and conventional care use is needed. In developing future studies, researchers should focus on improving the overall measurement of CAM use. Researchers have been critical of how CAM use is measured because typical approaches emphasize therapies and modalities used by white, middle-class adults and overlook therapies and treatments commonly used among ethnic minorities, like home remedies.19 Research that adequately captures both general and ethnic-specific forms of CAM is needed to definitively determine if the CAM-conventional care association differs by ethnicity. Additionally, future studies should include non-English-speaking study participants because both the NHIS and the MEPS, which is based on NHIS respondents, exclude non-English-speaking participants. To the extent that immigrants’ use of CAM changes as they become more acculturated, ethnic variation in the link between CAM and conventional care may be muted if less acculturated individuals are not studied.

The results of this study also suggest that the conventional care-CAM link is not linear. The complex survey design procedures used in the NHIS do not allow a formal test of the assumption of proportional odds; nevertheless, inspection of the estimated odds ratios for CAM use across the various modalities indicates significant overlap in the 95% confidence intervals for adjacent categories of the outcome. For example, in the “any CAM” model, there is significant overlap in the 95% confidence intervals for 1 visit and 2-3 visits, and for the 6-9 and 10+ visits. However, the estimated odds ratios and confidence intervals for both the 1 and 2-3 visits are well below the estimates for 6-9 and 10+ visits. These and similar results from other models in Tables 2 and 3 suggest that the CAM-conventional care association is stronger at higher levels of conventional care use. Although we cannot discern from these cross-sectional data whether CAM precedes, follows, or coincides with use of conventional care, the results are consistent with models of health self-management suggesting that individuals will engage in a wider variety of therapies as health deteriorates to accommodate the deficiencies or ameliorate the disadvantages of specific therapies.8

The last contribution of this study was evidence suggesting that the strength of the CAM-conventional care association differs by type of CAM. At every level of conventional care the estimated odds ratios for manipulative and body-based methods were stronger than odds ratios for other forms of CAM. Conversely, the estimated odds ratios for biologically based therapies were generally smaller than estimated odds ratios for other forms of CAM across levels of conventional care. Although the general result was expected, the observed pattern is surprising. That is, recognizing that use of common biologically based methods like use of special diets and herbs is frequently recommended by conventional health care providers, a stronger connection with conventional health care was expected. By contrast, recognizing that alternative medicine systems and conventional health are informed by fundamentally different philosophical traditions, it was expected that users of these modalities would systematically report less use of conventional care. Although more research is needed, these results suggest that CAM users may be less concerned with principles or ideologies underlying CAM therapies26 and more interested in finding therapies that help them feel “healthy.”

This study is not without limitations. First, use of conventional care was operationalized with a single item asking about the frequency of visits in the past year. Importantly, although the item used to assess conventional care use was clearly situated in a section of the interview focused on use of the conventional health care delivery system, it is possible that participants included visits to CAM practitioners in their response to the question used to operationalize level of conventional care use. Indeed, it is possible that the notably strong link between use of manipulative and body-based methods and conventional care use may be an artifact of individuals’ including visits to chiropractors in their response to the question believed to tap conventional medicine use. Next, the Alternative Health Supplement of the National Health Inter view Survey required individuals to report on their use of complementary medicine over the past 12 months. The 12-month look-back feature raises questions about possible recall bias and the bias that observed age-related effects may be an artifact of differential reporting by age. Further, as mentioned earlier, there is no way to determine in these cross-sectional data if use of CAM preceded, followed, or coincided with conventional care use, thereby creating problems for interpreting observed associations. Additionally, although lengthy, the NHIS asked about a limited number of CAM therapies that did not include therapies widely used by minority adults like home remedies.27 Finally, the cross-sectional design of the NHIS makes it impossible to differentiate age from cohort effects.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the literature on the linkage between CAM and conventional medicine in the general population. It is based on the largest and most representative study of CAM use in the US population to date. Although others have examined the CAM-conventional care association with these data,9 this is the first study to examine associations between levels of conventional care use and specific CAM modalities. The findings demonstrate that regardless of type of CAM, use of conventional care is greater among CAM users than nonusers. However, the strength of the CAM-conventional care link differs by age and type of CAM. Further research should investigate whether age-related differences in the CAM-conventional care link is attributed to age-related differences in the types of conditions for which treatment is being used or possible age-related differences in beliefs about CAM. Similarly, future research should determine why some types of CAM are more strongly linked to conventional care than others are.

Acknowledgment

The research was supported by grants AT002241 and AT003635 from the National Center on Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

Contributor Information

Joseph G. Grzywacz, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC..

Sara A. Quandt, Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Epidemiology and Prevention, Winston-Salem, NC..

Rebecca Neiberg, Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Biostatistical Sciences, Winston-Salem, NC..

Wei Lang, Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Biostatistical Sciences, Winston-Salem, NC..

Ronny A. Bell, Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Epidemiology and Prevention, Winston-Salem, NC..

Thomas A. Arcury, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC..

REFERENCES

- 1.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246–252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ni H, Simile C, Hardy AM. Utilization of complementary and alternative medicine by United States adults: results from the 1999 national health interview survey. Med Care. 2002;40:353–358. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200204000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu Tom K, Farrell TW. The complementarity and substitution between unconventional and mainstream medicine among racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:811–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arcury TA, Bell RA, Snively BM, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use as health self-management: rural older adults with diabetes. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61:S62–S70. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.s62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Van Rompay MI, et al. Perceptions about complementary therapies relative to conventional therapies among adults who use both: results from a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:344–351. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-5-200109040-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grzywacz JG, Lang W, Suerken CK, et al. Age, race, and ethnicity in the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for health self management: evidence from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. J Aging Health. 2005;17:547–572. doi: 10.1177/0898264305279821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorne S, Paterson B, Russell C, Schultz A. Complementary/alternative medicine in chronic illness as informed self-care decision making. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39:671–683. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(02)00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pagán JA, Pauly MV. Access to conventional medical care and the use of complementary and alternative medicine. Health Aff. 2005;24:255–262. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung CL. Asian Patients’ distrust of western medical care: one perspective. Mt Sinai J Med. 1999;66:259–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MRC Vitamin Research Group Prevention of neural tube defects: Results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. Lancet. 1991;338:131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, D. a. T. Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA. 2001;285:785–795. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.6.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heber D, Yip I, Ashley JM, et al. Cholesterol-lowering effects of a proprietary Chinese red-yeast-rice dietary supplement. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(2):231–236. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao SP, Liu L, Cheng YC, et al. Xuezhikang, an extract of cholestin, protects endothelial function through antiinflammatory and lipid-lowering mechanisms in patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2004;110:915–920. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000139985.81163.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X, Qin X, Demirtas H, et al. Efficacy of folic acid supplementation in stroke prevention: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;369:1876–1882. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60854-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Nonhormonal therapies for menopausal hot flashes: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:2057–2071. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;343:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grzywacz JG, Suerken CK, Neiberg RH, et al. Age, ethnicity, and use of complementary and alternative medicine in health self-management. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48:84–98. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arcury TA, Grzywacz JG, Bell RA, et al. Herbal remedy use as health self-management among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62B:S142–S149. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lurie N, Zhan C, Sangl J, et al. Variation in racial and ethnic differences in consumer assessments of health care. Am J Manag Care. 2003;9:502–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arcury TA, Suerken CK, Grzywacz JG, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among older adults: Ethnic variation. Ethn Dis. 2006;16:723–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham RE, Ahn AC, Davis RB, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medical thera pies among racial and ethnic minority adults: results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:535–545. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Upchurch DM, Chyu L, Greendale GA, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among American women: Findings from The National Health Interview Survey, 2002. J Womens Health. 2007;16:102–113. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.M074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sirois FM, Gick ML. An investigation of the health beliefs and motivations of complementary medicine clients. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler RC, Davis RB, Foster DF, et al. Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:262–268. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-4-200108210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1548–1553. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grzywacz JG, Arcury TA, Bell RA, et al. Ethnic differences in elders’ home remedy use: Sociostructural explanations. Am J Health Behav. 2006;30:39–50. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2006.30.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]