Abstract

Biosynthetic investigation of quinonemethide triterpenoid 22β-hydroxy-maytenin (2) from in vitro root cultures of Peritassa laevigata (Celastraceae) was conducted using 13C-precursor. The mevalonate pathway in P. laevigata is responsible for the synthesis of the quinonemethide triterpenoid scaffold. Moreover, anatomical analysis of P. laevigata roots cultured in vitro and in situ showed the presence of 22β-hydroxy-maytenin (2) and maytenin (1) in the tissues from transverse or longitudinal sections with an intense orange color. MALDI-MS imaging confirmed the distribution of (2) and (1) in the more distal portions of the root cap, the outer cell layers, and near the vascular cylinder of P. laevigata in vitro roots suggesting a role in plant defense against infection by microorganisms as well as in the root exudation processes.

The metabolic engineering of plants has been a relevant biotechnological tool for the production of secondary metabolites1. Root cultures can provide an alternative approach for producing important phytochemicals, as well as for understanding their biosynthetic pathways2. Camptothecin, vinblastine and ginsenosides are examples of important secondary metabolites stored in roots3,4. Hence, roots have been studied to induce and culture in vitro systems, such as adventitious root cultures, that are not infected with Agrobacterium rhizogenes2. Adventitious roots are natural and genetically well-established organs, in contrast to cultured plant cell suspensions, and they are useful for biosynthetic investigation as well as for biotechnological applications5,6. Cytotoxic triterpenoids that accumulate in adventitious roots are of great interest due to their extensive range of biological activity, especially in their potential effects against human tumor cell lines7,8. Recently, a subclass of terpenoids, namely quinonemethide triterpenoids, has been found to display notable antitumor activity against myeloma cell proliferation9, hepatocellular carcinoma cells10, prostate cancer cells11, glioblastoma cells12 and pancreatic cancer cells13. A terpenoid is synthesized in nature through one of two pathways involved in the biosynthesis of isoprene units (IPP), the mevalonate (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways14. Both the MVA and MEP pathways are localized in individual cellular compartments: the MVA pathway is located in the cytosol and the MEP pathway in the plastids15. The MVA pathway has long been known for triterpene biosynthesis16 and despite several studies on the MEP pathway, its complex regulation mechanism has not yet been fully clarified14. Although quinonemethide triterpenoid biosynthesis has not yet been investigated, there is one report on how mevalonic acid is responsible for IPP building blocks and also that friedelin (friedelane triterpenoid) is a primary precursor of maytenin and pristimerin17.

Here, we show for the first time the complete biosynthetic origin of the IPP units in maytenin (1) and 22β-hydroxy-maytenin (2) accumulated in in vitro root cultures of Peritassa laevigata (Hoffmanns. ex Link) A.C.Sm. using the incorporation of 1-13C-D-glucose as a 13C-labeled precursor. Besides, we carried out anatomical analysis from in vitro root and in situ root cultures and MALDI imaging from in vitro roots to localize the compartmentalization of compounds 1 and 2 in root cells.

Results

Quantification of 1 and 2 from in vitro and in situ root cultures of P. laevigata

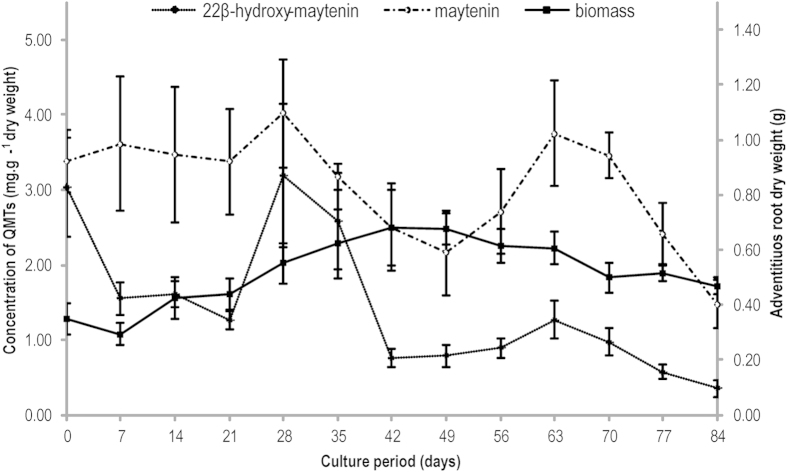

In vitro root cultures were established from the cotyledon of P. laevigata. Maytenin (1) and 22β-hydroxy-maytenin (2) were the major compounds found in in vitro roots from P. laevigata, and there is no previous study in the literature reporting its chemical composition. Higher accumulation of quinonemethide triterpenes [4.02 ± 0.72 mg.g−1 of 1 and 3.20 ± 0.95 mg.g−1 of 2] occurred at 28 days for in vitro roots cultivated from P. laevigata (Fig. 1). In situ roots from P. laevigata accumulated 7.76 ± 0.02 mg.g−1 of 1 and 0.47 ± 0.08 mg.g−1 of 2 in a 3-year-old cultivation, while roots from ten-year-old plants cultured in situ produced 8.54 ± 0.95 mg.g−1 of 1 and 0.54 ± 0.04 mg.g−1 of 2 in a 10-year-old cultivation (Table 1).

Figure 1. Quantification of maytenin (1) and 22β-hydroxy-maytenin (2) in P. laevigata adventitious roots cultured in vitro (dry weight).

The roots were cultured for 84 days under dark conditions in WPM medium supplemented with 2% glucose (w/v), PVP (899.74 μM), and IBA (19.68 μM).

Table 1. Quantification of maytenin (1) and 22β-hydroxy-maytenin (2) in roots from 3-year-old and 10-year-old P. laevigata cultured in situ.

| In situ roots | 22β-hydroxy-maytenin (mg.g−1) | maytenin(mg.g−1) |

|---|---|---|

| 3-year-old | 0.47 a | 7.76 a |

| 10-year-old | 0.54 a | 8.54 a |

Scott-Knott test (p < 0.05).

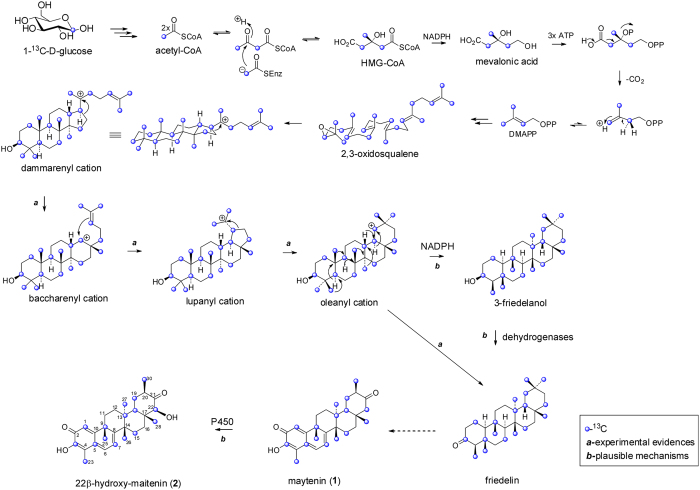

Biosynthetic origin of quinonemethide triterpenoids from P. laevigata roots cultured in vitro

To observe the biosynthetic pathway of the target quinonemethide triterpenoids, in vitro roots were cultured in Murashige & Skoog medium18 supplemented with 1-D-13C-glucose precursor for 30 days. A chloroform extract from fresh root cultures of P. laevigata was then prepared and fractioned by column chromatography to yield 2. The incorporation pattern was determined by quantitative 13C NMR by comparing the relative intensities of the labeled and non-labeled signals for 2. After 1-13C-D-glucose metabolism, the 13C-enrichment pattern of 2 showed that the positions C-1, C-3, C-5, C-7, C-9, C-13, C-15, C-18, C-19, C-22, C-23, C-25, C-26, C-27, C-28 and C-30 (Fig. S2, Table S1 - Supplementary Information) were highly labeled with 13C (3.1% to 6.3% range). The MVA pathway generates an IPP unit enriched in C-2, C-4 and C-5 while an IPP unit from the MEP pathway is enriched in C-1 and C-5. Obtained data confirm that the IPP building units were biosynthesized exclusively by the MVA pathway since quinonamethide triterpenes are biosynthesized by 6 IPP units, and therefore 18 C-positions would be labeled, however only 16 C-positions labeled were found (Fig. 2 and Table S1- Supplementary Information). A hypothesis could be that two methyl groups undergo further descarboxylation reaction (Fig. S3-Supplementary Information). The initial precursor chair–chair–chair–boat conformation of 2,3-oxidosqualene undergoes a series of Wagner–Meerwein rearrangements, first hydride migration generating a new cation followed by 1,2-methyl rearrangement19. The dammarenyl cation (tertiary cation) then undergoes ring expansion, giving the baccharenyl cation. The baccharenyl cation is converted to a 5-membered ring followed by the formation of the tertiary lupanyl carbocation. Wagner–Meerwein 1,2-methyl rearrangement of the lupanyl cation occurs, leading to an oleanyl cation19. The oleanyl cation is converted to friedelin, a key precursor of quinonemethide triterpenes20. Regarding friedelin, the hypothetical pathway also involves sequential oxidations, most likely by cytochrome P450 enzymes, which may catalyze more than one oxidation reaction leading to intermediates such as celastrol and maytenin (1). Then, maytenin (1) is converted to 22β-hydroxy-maytenin (2) through one stereospecific hydroxylation at position C-22, and the presence of both is confirmed in root cultures (Fig. 2 and Fig. S3-Supplementary Information).

Figure 2. Biosynthetic studies using 1-13C-D-glucose as precursor showed that the biosynthesis of quinonemethide triterpenoids 1 and 2 proceeds via mevalonate pathway.

Anatomical studies of P. laevigata roots

It has been reported that quinonemethide triterpenoids are produced and accumulate in roots of several Celastraceae species17, and understanding their unexplored biosynthesis is a fundamental step to manipulate their production. In addition, their tissue distribution, which has not yet been investigated, could contribute to identify their functions in the tissue and in root the exudation process21, and also to improve biotechnological manipulation. The in vitro root culture showed typical root anatomy (Fig. S4-S9 Supplementary Information). Numerous black starch grains were observed in cells of cortical parenchyma from in vitro roots (Fig. S4A-B Supplementary Information), similar to that observed for ex vitro roots (Fig. S4C-D Supplementary Information) when stained with Lugol, and the shapes of starch grains were visualized by polarized light, as observed for in vitro (Fig. S5A Supplementary Information) and in situ roots (Fig. S5B Supplementary Information). Transversal sections of in vitro and in situ roots without dye stabilization showed an accumulation of orange color compounds detected in endoderm and cortical parenchyma cells from in vitro (Fig. S6A,C Supplementary Information) and in situ roots (Fig. S6B,D Supplementary Information), suggesting the compartmentalization of compounds 1 and 2, as already reported for in vitro roots of Peritassa campestris that substances that have been isolated have an intense orange color22,23,24,25. The longitudinal sections of in vitro culture roots (Fig. S9 Supplementary Information), with no stain applied, showed more intense orange color in the region of root primary structure (Fig. S9C Supplementary Information) compared to near to root cap (Fig. S9A Supplementary Information), which denotes a possible higher accumulation of orange color compounds in outer layer cells. Subsequently their chemical identification and tissue distribution were confirmed by MALDI imaging. In addition, the transversal (Fig. S7A,B Supplementary Information) and longitudinal (Fig. S7C, Fig. S8A–C Supplementary Information) sections of in vitro roots were stained with safranine/astra blue and the distributions of the primary and secondary cell walls were determined in the tissue, confirming its common root anatomy. Details of xylematic elements stained pink using safranin/astra blue dye could be observed by longitudinal sections (Fig. S7C Supplementary Information).

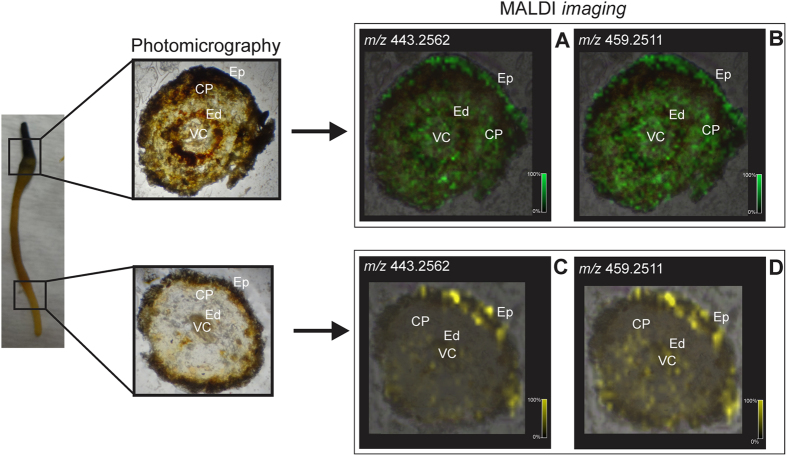

Compartmentalization and tissue distribution of quinonemethide triterpenoids (1–2) of in vitro root cultures from P. laevigata by MALDI imaging

The identity and distribution of compounds 1 and 2 was confirmed by MALDI imaging, an emerging technique for visualization of metabolite distributions in plant tissues26,27,28,29. Firstly, the standards were analyzed by MALDI-MS and MS/MS and it was possible to detect their sodiated ions and a reduction of source fragmentation after sodium addition. Subsequently, transverse sections of in vitro roots were analyzed by MALDI imaging. The images reconstructed with ions of 1 (m/z 443.2562 [M + Na]+) and 2 (m/z 459.2511 [M + Na]+), which showed higher ion intensities in the distal portions than near the root cap, demonstrated higher accumulation in older tissues (Fig. 3, Fig. S10 Supplementary Information). Moreover, higher ion intensity was observed in the endoderm and outer cell layers (Fig. 3A,B), but they were extensively detectable in tissues such as the cortical parenchyma.

Figure 3.

Transverse sections of root tissues from Peritassa laevigata obtained from different parts (root cap, differentiating region, and primary structure) and their MALDI-MS images reconstructed with ions m/z 443.2562 [M + Na]+ (A,C) and 459.2511 [M + Na]+ (B,D) corresponding to maytenin (1) and 22β-hydroxy-maytenin (2), respectively. CP: cortical parenchyma; Ed: endoderm; Ep: epiderm; VC: vascular cylinder.

Discussion

Unlike most plant species, the maximum accumulation of quinonemethide triterpenes in P. laevigata in vitro roots preceded biomass enhancement, corroborating the results obtained with Celastraceae species cultured in vitro30,31,32. P. laevigata roots cultured in vitro produced 1.3 times more compound 2 compared to roots of 10-year-old plants cultured in situ, although yields of compound 1 was 3.3 fold higher in P. laevigata roots grown in situ. Our data suggest that sub-cultivation of roots could be highly advantageous, considering that roots cultured in vitro for four months produced the same amount of 1 and five times more the amount of 2 compared to the production in roots of 10-year-old plants cultured in situ. There is no statistical significance between the quinonemethide triterpenes amount of 3-year-old and 10-year-old in situ roots. Moreover, the production of 2 in P. laevigata roots cultured in vitro was superior compared to other Celastraceae species, including Peritassa campestres and Maytenus ilicifolia30,31,32. The cultivation of differentiated organs, such as root culture obtained from P. laevigata, can significantly improve the accumulation of secondary metabolites often considered cytotoxic, such as quinonemethide triterpenes, which are present in cells specialized for storage of compounds at specific stages of development. Compounds 1 and 2 could be related to protection against microorganisms, justifying their tissue distributions (higher ion intensities) in the outer cell layers and near the vascular cylinder, as they showed significant antimicrobial activity8,33, as well as facilitating the exudation processes toward growth medium, as observed in Catharanthus roseus34 and other species21. Roots are able to secrete defense compounds into the rhizosphere and this process is regulated by endogenous and exogenous stimuli. In fact, cap and border cells are involved in the development of roots and these cells act as a defensive barrier of roots protecting the plant against pathogen invasion21,35. More recently, it was reported that exudation of the isoflavonoid pisatin and the construction of the root border cell is stimulated in pea when root tips are challenged with a plant pathogen. Besides, exogenous pisatin leads to the upregulation of border cell production in vitro35. The production of antimicrobial naftoquinones and epidermal and outer layer cells increased, after the fungal elicitation in Lithospermum erythrorhizon roots36. Similar tissue distribution was observed in our study, and these findings together with the effective antimicrobial activity observed for maytenin and 22-β-hydroxy-maytenin33,37, suggest there are functions related to exudation and the antimicrobial protection. Altogether, our results regarding the biosynthesis of quinonemethide triterpenoids in P. laevigata have shown that they are constructed by the MVA pathway, and the route is compartmentalized in the cytosol. This study provides the first experimental evidence of quinonemethide triterpenoid biosynthesis using a 13C-precursor and shows the production and tissue distribution of quinonemethide triterpenoids in P. laevigata roots cultured in vitro using the MALDI imaging mass spectrometry. Obtained data present the possibility of developing large-scale production of quinonemethide triterpenoids, achieving greater levels than that produced by plants in situ, to supply the pharmaceutical industry with anticancer compounds and also to provide support for the manipulation of the biosynthesis of those compounds by biotechnological processes.

Methods

Chemical

The 1-13C-D-glucose was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich®. The matrices 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) were purchased from Bruker Daltonics.

Plant materials

The specimen was identified by Dr. Julio Antonio Lombardi (Instituto de Biociências, UNESP, Rio Claro, SP). A voucher specimen, under access number 2389, was deposited at the Herbarium of Medicinal Plants of the University of Ribeirão Preto (HPM-UNAERP, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil). Seeds from P. laevigata were collected in the region of Água Limpa, MS, Brazil (November, 2010) and surface sterilized using a 1% captan solution (Orthocide® 500) and thiophanate-methyl (Cercobin® 700WP) for 24 h. After this period, seeds were transferred to a solution containing ampicillin, cefotaxime, gentamicin and streptomycin (10 mg.L−1 of each antibiotic) for another 24 h. Then, the seeds were immersed in calcium hypochlorite (0.5%) for 30 min, washed three times with distilled water and inoculated on semi-solid basal Murashige & Skoog medium supplemented with 30 g.L−1 sucrose and 2.5 g.L−1 Phytagel®. The explants were kept in a culture room at 25 ± 2 °C, 55–60% relative humidity under a 16/8 h photoperiod (light/dark). After 90 days of culture, cotyledons were excised and transferred to culture medium containing basal WPM medium supplemented with IBA (19.68 μM), PVP (899.74 μM), Phytagel® (2.5 g.L−1) and glucose (20 g.L−1) and pH adjusted to 6.0, for root induction. Cotyledon segments presenting adventitious root formation were transferred to Erlenmeyer flasks containing the same culture medium described above (without Phytagel®) and placed on an orbital shaker (90 rpm) in the dark. In vitro root cultures were subcultured in a 60-day interval. Quinonemethide triterpenes 1 and 2 were quantified by biomass growth curves in the same culture medium used for root induction. For each sample, an initial inoculum of P. laevigata roots (2.00 ± 0.20 g) was placed into an Erlenmeyer flask (250 mL) containing 100 mL of culture medium and kept in growth chamber at 25 ± 2 °C, in the dark, on an orbital shaker under 90 rpm agitation. Sample root collection was performed for 84 days starting at day 0 (cultivation start). Roots cultured in vitro were removed from the culture medium (n = 9), weighed and dried in a circulating air oven for 48 h at 43 °C at seven-day intervals. Roots from 3-year-old (n = 3) and 10-year-old (n = 3) plants grown in situ collected from the field (UNAERP, Ribeirao Preto, SP - Brazil), were dried in circulating air oven for 48 h at 43 °C for seven days.

General procedure for biosynthesis experiments from P. laevigata roots cultured in vitro

In vitro root cultures (twenty Erlenmeyers containing 3.0 g each) were maintained for a 60-day interval in basal WPM medium supplemented with IBA (19.68 μM), PVP (899.74 μM) and 1-D-13C-glucose (20 g.L−1) and pH adjusted to 6.0. In vitro roots (control) were cultivated with the same culture medium described above using D-glucose. The medium was able to induce younger roots after 2 weeks of culture under a cycle of 16 h light/8 h dark with continuous growth until 35 days.

General procedure for the isolation of quinonemethide triterpenoids (1 and 2)

After 35 days, in vitro root cultures were extracted with chloroform for 14 h. The resulting extract (243.8 mg) was fractionated by column chromatography over silica gel (70–230 mesh; Merck, column size 9.0 × 2.0 cm) with n-hexane-EtOAc (7:3) as the mobile phase and with increasing amounts of EtOAc (up to 30%) to yield seven fractions. Fraction 2 (35 mg) was further purified via column chromatography over silica gel (70–230 mesh; Merck, column size 5.0 × 1.2 cm) using n-hexane-EtOAc (8:2) to yield 1 (5.0 mg). Fraction 5 (20 mg) was further purified via column chromatography over silica gel (70–230 mesh; Merck, column size 5.0 × 1.2 cm) using n-hexane-EtOAc (6:4) to yield 2 (8.0 mg).

HPLC analysis

Dried plant material from roots cultured in vitro and in situ (1 g), was extracted with chloroform for 12 h to obtain the crude extract, and the sample preparation for quantitative HPLC analysis of 1 and 2 was performed as previously described by our group and colaborators17,31. HPLC analyses were carried out using the Shimadzu instrument (LC-10-AVP) system. The quantification of compounds 1 and 2 was performed on a Phenomenex - Luna (C-18) column 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μ particle size, using a isocratic mobile phase, methanol/water/formic acid (80 : 20 : 0.1, v/v/v) for 20 min., 1.0 mL.min−1 flow rate; detection at 420 nm). Compounds 1 and 2 were detected at 9.22 min and 10.87 min, respectively, and the amount of compounds were calculated from a calibration curve (triplicate, prepared in acetonitrile at concentrations of 31.0, 63.0, 125.0, 250.0 and 500.0 μg.mL−1 for 1 and 7.81, 15.63, 31.25, 62.50 and 125.0 μg.mL−1 for 2; Fig. S1 - Supplementary Information). The statistical analysis Scott-Knott test (P\0.05) was applied.

NMR analysis

NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 MHz spectrometer using CDCl3 as the solvent and internal standard. The relative 13C enrichments were obtained by comparing the relative intensity of the labeled signal and the natural abundance of quinonemethide triterpenoids. The combination of 1D and 2D NMR experiments allowed complete elucidation consistent with the literature values38. All NMR spectra are described in the supplementary material.

Sample preparation

The roots were transversely sectioned in a Leica RM2245 microtome at a thickness of 30 μm, and photomicrographs were obtained with a Leica DM 500 photomicroscope.

MALDI imaging analyses

The MALDI imaging analyses were performed using a MALDI-TOF/TOF UltrafleXtreme (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany), equipped with an 1KHz smartbeam II laser and operating in reflectron positive ion mode. The transverse sections of roots were adhered with double-sided tape (3 M Co., USA) to indium tin oxide-coated conductive slides (Bruker Daltonics) for MALDI analysis. The matrix (DHB:CHCA 7:3 (w/w) was prepared at a concentration of 10 mg/mL with the addition of 0.15 mg/mL NaCl using acetonitrile and deionized water (9:1, v/v). The matrix was applied to the tissue by an ImagePrep station, and N2 flux was used in the entire spraying process. The instrumental conditions employed were as follows: ion source 1 of 25.00 kV, ion source 2 of 22.55 kV, pulsed ion extraction 110 ns, laser frequency 1000 Hz, minimum laser setting and 800 shots. The external calibration was performed using a flavonoid mixture (galangin, rutin, quercetin and isoquercetin). The images were collected at 25 μm spatial resolution in both the x and y directions. The spectra were calibrated internally using matrix ions and a corrected baseline. The tissue analysis of different parts of the roots (differentiating region and root primary structure) were analyzed together using different region of interest to compare the ion intensities and to apply the same processing parameters. The images were normalized, and a logarithm ion intensity scale was applied.

Histochemical analyses

The root anatomy was analyzed in transverse and longitudinal sections stained with safranine/astra blue (safrablau) and lugol to detect starch and total lipids and terpenes into the root tissues, respectively. Lugol solution yielded a blue-black color in the presence of starch, while safrablau solution yielded a blue color in the presence of primary cell walls and a pink color for secondary cell walls (xylematic elements). Starch was also checked using polarized light. Unstained sections were also analyzed and photographed. All the images are presented in the supplementary material.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Pina, E. S. et al. Mevalonate-derived quinonemethide triterpenoid from in vitro roots of Peritassa laevigata and their localization in root tissue by MALDI imaging. Sci. Rep. 6, 22627; doi: 10.1038/srep22627 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the São Paulo Research Foundation - FAPESP (Process: 2009/54098-6, 2010/18132-2, 2012/18031-7, 2013/07349-9, 2014/50265-3 and 2015/26066-3), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES). In addition, the authors would like to thank FAPESP for the article processing charge payment.

Footnotes

Author Contributions A.A.L., A.M.S.P. and N.P.L. conceived and designed the research; E.S.P., A.A.L. and J.S.C. contributed in running the laboratory work. D.B.S. and S.P.T. conducted the histochemical analyses. D.B.S. and N.P.L. carried out the MALDI imaging experiments. A.A.L., D.B.S. and A.M.S.P. wrote the manuscript and A.M.S.P., S.C.F., N.P.L. and M.F. analyzed, interpreted obtained data and revised the paper.

References

- Runguphan W. & O’Connor S. E. Metabolic reprogramming of periwinkle plant culture. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 151–153 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S. & Chandra R. Engineering secondary metabolite production in hairy roots. Phytochem. Rev. 10, 371–395 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar G. Bioreactor technology: A novel industrial tool for high-tech production of bioactive molecules and biopharmaceuticals from plant roots. Biotechnol. J. 1, 1419–1427 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baque M. A., Moh S., Lee E., Zhong J. & Paek K. Production of biomass and useful compounds from adventitious roots of high-value added medicinal plants using bioreactor. Biotechnol. Adv. 30, 1255–1267 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy H. N., Hahn E. J. & Paek K. Y. Adventitious roots and secondary metabolism. Chin. J. Biotech. 24, 5, 711–716 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy H. N., Dandin V. S. & Paek K. Tools for biotechnological production of useful phytochemicals from adventitious root cultures. Phytochem. Rev. 15, 1, 129–145 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Kuo R., Qian K., Morris-Natschke S. L. & Lee K. Plant-derived triterpenoids and analogues as antitumor and anti-HIV agents. Nat. Prod. Rep. 26, 1321–1344 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang K., Huang J., Pan J., Zhang X. & Lu W. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of C(6)-indole celastrol derivatives as potencial antitumor agents. RSC Adv. 5, 19620–19623 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Ni H., Zhao W., Kong X., Li H. & Ouyang J. NF-Kappa B modulation is involved in celastrol induced human multiple myeloma cell apoptosis. Plos One 9, e95846, 1–8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y. et al. Celastrol enhanced the anticancer effect of lapatinib in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro. J. Buon. 19, 412–418 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. B. et al. Ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation of antiapoptotic survivin facilitates induction of apoptosis in prostate cancer cells by pristimerin. Int. J. Oncol. 45, 1735–1741 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boridy S., Le P. U., Petrecca K. & Maysinger D. Celastrol targets proteostasis and acts synergistically with a heat-shock protein 90 inhibitor to kill human glioblastoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1216, 1–12 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeb D., Gao X., Liu Y. B., Pindolia K. & Gautam S. C. Pristimerin, a quinonemethide triperpenoid, induces apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells through the inhibition of pro-survival Akt/NF-kB/mTOR signaling proteins and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2. Int.J. Oncol. 44, 1707–1715 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W., Song H., Liu H. & Liu P. Current development in isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis and regulation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 17, 571–579 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz S., Nes W. D. & Gershenzon J. Both methylerythritol phosphate and mevalonate pathways contribute to biosynthesis of each of the major isoprenoid classes in young cotton seedlings. Phytochemistry 98, 110–119 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimmappa R., Geisler K., Louveau T., O’Maille P. & Osbourn A. Triterpene biosynthesis in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65, 225–57 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsino J. et al. Biosynthesis of friedelane and quinonemethide triterpenoids is compartmentalized in Maytenus aquifolium and Salacia campestris. Phytochemistry 55, 741–748 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T. & Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays in tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant. 15, 473–497 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- Dewick P. M. In Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach 3rd ed., (ed Dewick P. M.) Ch. 5, 235–240 (John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Yeats T., Han H. & Jetter R. Cloning and characterization of oxidosqualene cyclases from Kalanchoe daigremontiana. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 39, 29703–29712 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z., Kastell A., Knorr D. & Smetanska I. Exudation: an expanding technique for continuous production and release of secondary metabolites from plant cell suspension and hairy root cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 31, 461–477 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaić L., Morimoto R. I. & Silverman R. B. Celastrol Analogues as Inducers of the Heat Shock Response. Design and Synthesis of Affinity Probes for the Identification of Protein Targets. ACS Chem. Biol. 7, 5, 928–937 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues-Filho E., Battos F. A. P., Fernandes J. B. & Braz-Filho R. Detection and identification of quinonemethide triterpenes in Peritassa campestris by mass spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 16, 627–633 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeller A. H., Silva D. H. S. S., Lião L. M., Bolzani V. S. & Furlan M. Antioxidant phenolic and quinonemethide triterpenes from Cheiloclinium cognatum. Phytochemistry 65, 1977–1982 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunatilaka A. A. L., Tamm C. & Walser-Volken P. In Fortschritte Der Chemie Organischer Naturstoffe Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products 1st ed., Vol. 67 (eds Herz W. et al.), Triperpenoid Quinonemethides and Related Compound (Celastroids), 1–24 (Springer-Verlag, Wien, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Silva D. B. et al. Mass spectrometry of flavonoid vicenin-2 based sunlight barriers in Lychnophora species. Sci. Rep. 4, 4309 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. J., Perdian D. C., Song Z., Yeung E. S. & Nikolau B. J. Use of mass spectrometry for imaging metabolites in plants. Plant J. 70, 81–95 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnholt N., Li B., D’Alvise J. & Janfelt C. Mass spectrometry imaging of plant metabolites –principles and possibilities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 31, 818–837 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K., Kozuka T., Anegawa A., Nagatani A. & Mimura T. Development and application of a high-resolution imaging mass spectrometer for the study of plant tissues. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 1329–1338 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffa-Filho W. et al. In vitro propagation of Maytenus ilicifolia (Celastraceae) as potential source for antitumoral and antioxidant quinomethide triterpenes production. A rapid quantitative method for their analysis by reverse-phase high- performance liquid chromatography. Arkivoc 6, 137–146 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Paz T. A. et al. Production of the quinone-methide triterpene maytenin by in vitro adventitious roots of Peritassa campestris (Cambess.) A.C.Sm. (Celastraceae) and rapid detection and identification by APCI-IT-MS/MS. BioMed Res. Int., 2013, 485837, 1–7 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppede J. S. et al. Cell cultures of Maytenus ilicifolia Mart. are richer sources of quinone-methide triterpenoids than plant roots in natura. Plant Cell Tissue and Organ Culture 118, 33–43 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Gullo F. P. et al. Antifungal activity of maytenin and pristimerin. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012, 340787, 1–6 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Peebles C. A. M., Shanks J. V. & San K. Effect of sodium nitroprusside on growth and terpenoid indole alkaloid production in Catharanthus roseus hairy root cultures. Biotechnol. Prog. 27, 625–630 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baetz U. & Martinoia E. Root exudates: the hidden part of plant defense. Trends Plant Sci. 2, 19, 90–98 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigham L. A., Michaels P. J. & Flores H. E. Cell-specific production and antimicrobial activity of naphthoquinones in roots of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Physiology 119, 417–428 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotanaphun U., Lipipun V., Suttisri R. & Bavovada R. Antimicrobial activity and stability of tingenone derivatives. Planta Med. 65, 450–452 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaishi Y. et al. Triterpenoid inhibitors of interleukin-1 secretion and tumour-promotion from Tripterygium wilfordii var. regelii. Phytochemistry 45, 969–974 (1997). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.