Abstract

Possible reasons for why a new study could not replicate our finding that the serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram decreased amyloid β concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid of healthy volunteers.

We read with great interest the Letter by Emilsson et al. (1) about our study, “An antidepressant decreases CSF Aβ production in healthy individuals and in transgenic AD mice” (2). Our study showed that the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), citalopram, decreased amyloid β (Aβ) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of healthy volunteers and in the brain interstitial fluid (ISF) of a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (2). We are particularly pleased that they attempted to replicate our findings in humans using CSF obtained 27 and 4 hours after a 20-mg oral dose of escitalopram, the active R-enantiomer of citalopram. Finally, we appreciate the suggestion by Emilsson and colleagues that a nonserotonergic mechanism related to the R-enantiomer of citalopram may explain our original results regarding the Aβ-modulating effect of citalopram. We believe, however, that two key methodological differences between the two studies (both noted by Emilsson et al. in their Letter) are more likely to explain the discrepancies in the findings.

These methodological differences relate to drug dose and timing of CSF sampling. Escitalopram has a half-life of about 28 hours (3). Consequently, given that Emilsson et al. gave the first dose of escitalopram 27 hours before CSF sampling, the drug concentration was reduced by 50% by the time of CSF sampling. Further, based on kinetic studies, it takes 6 hours after amyloid precursor protein (APP) is cleaved for changes in Aβ to be detected in the CSF (4, 5). Therefore, sampling CSF at 4 hours after the second drug dose means that the impact of that dose would not yet be present in the CSF. We think the study of Emilsson et al. is likely to have assessed the effect of about 10 mg of escitalopram on Aβ concentrations in CSF. In contrast, our study administered a total dose of 60 mg of citalopram over a 2-hour period and started measuring Aβ concentrations in CSF 6 hours after the second dose. Emilsson and colleagues likely sampled CSF Aβ when their active drug concentration was only 33% of what our equivalent dose would have been (taking into account that escitalopram has twice the effect on serotonin reuptake inhibition as citalopram). This considerable difference in drug doses between the two studies could account for the lack of effect on CSF Aβ reported in the Emilsson et al. Letter (1).

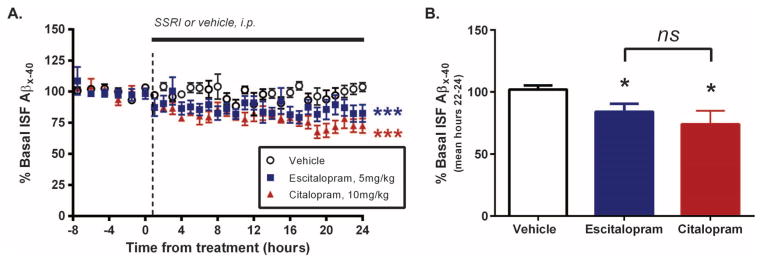

We have also conducted parallel studies in mouse models of AD. To date, we have tested five SSRIs (6) for their effect on Aβ concentrations in the brain ISF of APP transgenic and wild-type mice. In all cases, the SSRIs reduced ISF Aβ by 15 to 30%. We have now also tested the Aβ-lowering effect of escitalopram using a single dose of escitalopram in young APP/PS1+/− mice. We found that, similar to the other SSRIs, there was a 16% reduction in ISF Aβ by 24 hours after dosing (P = 0.03, n = 6) compared to vehicle (n = 6) (Fig. 1). In previous work (6), citalopram administered at 10 mg/kg also reduced ISF Aβ concentrations in mice by 26% (P = 0.001, n = 4) (Fig. 1). Citalopram and escitalopram were administered at comparable active-form doses to the APPswe/PS1dE9 hemizygous mice, and there was no significant difference between these two drugs (P = 0.302) regarding their effects on ISF Aβ. That said, the effect of escitalopram on ISF Aβ was not as robust as the effect of citalopram, suggesting that half a dose of escitalopram may not be quite as effective as citalopram in lowering Aβ. Importantly, direct infusion of serotonin into the mouse brain also mimicked the effects of the SSRIs (6). These data support our interpretation that increased serotonin signaling suppresses brain Aβ production, as opposed to an off-target effect of citalopram or one of the drug’s metabolites. We hope that future studies will define the signaling pathways that link serotonin receptors to Aβ metabolism, providing more confidence in the mechanism underlying this phenomenon.

Fig. 1. Effect of SSRIs on ISF Aβ concentrations in APP/PS1 transgenic mice.

(A) Young 3- to 4-month-old APP/PS1 hemizygous mice (pre-plaque) were implanted with unilateral microdialysis probes into the hippocampus [as described in (6)]. Baseline ISF Aβ concentrations were established in each mouse for 7.5 hours, and then mice were administered a single dose of either vehicle [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)], escitalopram (5 mg/kg), or citalopram (10 mg/kg) intraperitoneally (i.p.). ISF Aβ was measured every 60 min for an additional 24 hours. The citalopram data are from a previously published study (6), and the escitalopram data are from new studies using identical methods. Using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures and Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, there was a significant difference between the drug treatment groups compared to vehicle; ***P < 0.001. (B) By hours 22 to 24 after drug dosing, there was a 16.0 ± 6.4% (*P = 0.03, n = 6) and a 26.0 ± 5.4% (*P = 0.0013, n = 4) decrease in ISF Aβ with escitalopram and citalopram, respectively, compared to vehicle-treated mice (n = 6) (one-way ANOVA compared to vehicle; mean ± SEM). ns, not significant.

In summary, although Emilsson and colleagues present interesting findings in their Letter, differences in sampling times and drug dosing between their study and ours make it difficult to compare the two sets of results. Additional studies of the effects of SSRIs on Aβ in humans are needed, and especially studies that use higher doses of escitalopram and better CSF sampling methods, which would enable assaying of the maximal CSF concentrations of the drug.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Emilsson JF, Andreasson U, Blennow K, Eriksson E, Zetterberg H. Comment on “An anti-depressant decreases CSF Aβ production in healthy individuals and in transgenic AD mice”. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:268le5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheline YI, West T, Yarasheski K, Swarm R, Jasielec MS, Fisher JR, Ficker WD, Yan P, Xiong C, Frederiksen C, Grzelak MV, Chott R, Bateman RJ, Morris JC, Mintun MA, Lee JM, Cirrito JR. An antidepressant decreases CSF Aβ production in healthy individuals and in transgenic AD mice. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:236re4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prescribing information—Forest Laboratories. www.frx.com/pi/lexapro_pi.pdf.

- 4.Mawuenyega KG, Sigurdson W, Ovod V, Munsell L, Kasten T, Morris J, Yarasheski K, Bateman R. Decreased clearance of CNS β-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 2010;330:1774. doi: 10.1126/science.1197623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y, Potter R, Sigurdson W, Santacruz A, Shih S, Ju Y, Kasten T, Morris J, Mintun M, Duntley S, Bateman R. Effects of age and amyloid deposition on Aβ dynamics in the human central nervous system. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:51–58. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cirrito JR, Disabato BM, Restivo JL, Verges DK, Goebel WD, Sathyan A, Hayreh D, D’Angelo G, Benzinger T, Yoon H, Kim J, Morris JC, Mintun MA, Sheline YI. Serotonin signaling is associated with lower amyloid-β levels and plaques in transgenic mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:14968–14973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107411108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]