Summary:

This case report discusses the reconstruction of an entire thumb metacarpal after a diagnosis of giant cell tumor of bone. The patient underwent excision of the entire thumb metacarpal, followed by interposition of a tricortical iliac crest bone graft and metacarpophalangeal and carpometacarpal joint arthrodeses. This option allowed salvage of the patient’s native thumb with functional use as a stable post to which she can pinch and grasp objects. At 9 months postoperatively, there was no evidence of recurrence.

Giant cell tumor of bone (GCTB) is a rare, benign, and locally aggressive tumor, constituting 4–5% of all primary bone tumors and 18–20% of benign bone tumors.1,2 GCTB typically presents in women during the third and fourth decades of life and in meta-epiphyseal regions of long bones.3–7 However, hand and metacarpal involvement in GCTB is rare (1–4%), and although benign, it has been shown to metastasize to the lungs within 3 years after initial surgical treatment (3%).5,7–10

Treatment options include curettage, radiation, resection, or amputation.11,12 Numerous studies have shown that more aggressive treatments have lower rates of recurrence compared with that of simple curettage.3,5,7,13–15 However, wide excision or amputation can result in a large bony defect with possible joint involvement, necessitating functional reconstruction. This case report describes the resection of an entire thumb metacarpal bone secondary to a GCTB, followed by reconstruction with a tricortical iliac crest bone graft as a salvage procedure to preserve the patient’s native thumb and avoid amputation.

CASE REPORT

A 63-year-old woman presented to a hand surgery clinic with a 3-month history of an atraumatic, painless enlargement of the right thumb. Radiographs revealed a bubbly lytic lesion of the proximal thumb metacarpal with cortical destruction and surrounding soft-tissue edema (Fig. 1). Incisional biopsy confirmed GCTB. Computed tomographic scans of the chest, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast and a whole body nuclear medicine bone scan were all negative for metastasis.

Fig. 1.

View of giant cell tumor of thumb metacarpal preoperatively.

Surgical treatment options included salvage of the native thumb with bone graft reconstruction or amputation of the entire thumb with pollicization of the index finger or toe to thumb transfer. The patient elected for a staged reconstruction of the thumb metacarpal. First, all gross tumor and the involved thumb metacarpal were excised from the carpometacarpal joint to the distal metacarpal neck, measuring 3.8 × 2.9 × 2 cm. An external fixator and a bone cement spacer were placed temporarily to maintain thumb stability and length. Pathology revealed a locally aggressive tumor with cortical bone destruction and positive inked distal margin. There was no sarcomatoid change or vascular invasion.

At 3 weeks postoperatively, the external fixator and the spacer were removed, and the remaining distal segment of the metacarpal bone was fully excised, disarticulating the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint of the thumb. A nonvascularized, tricortical iliac crest bone graft was interspaced and fused to the MCP joint and carpometacarpal joints (Fig. 2). Pathology of the excised distal metacarpal bone revealed benign bone and no residual tumor. The patient was referred to Oncology department for observation. At 9 months postoperatively, radiographs revealed no signs of GCTB recurrence.

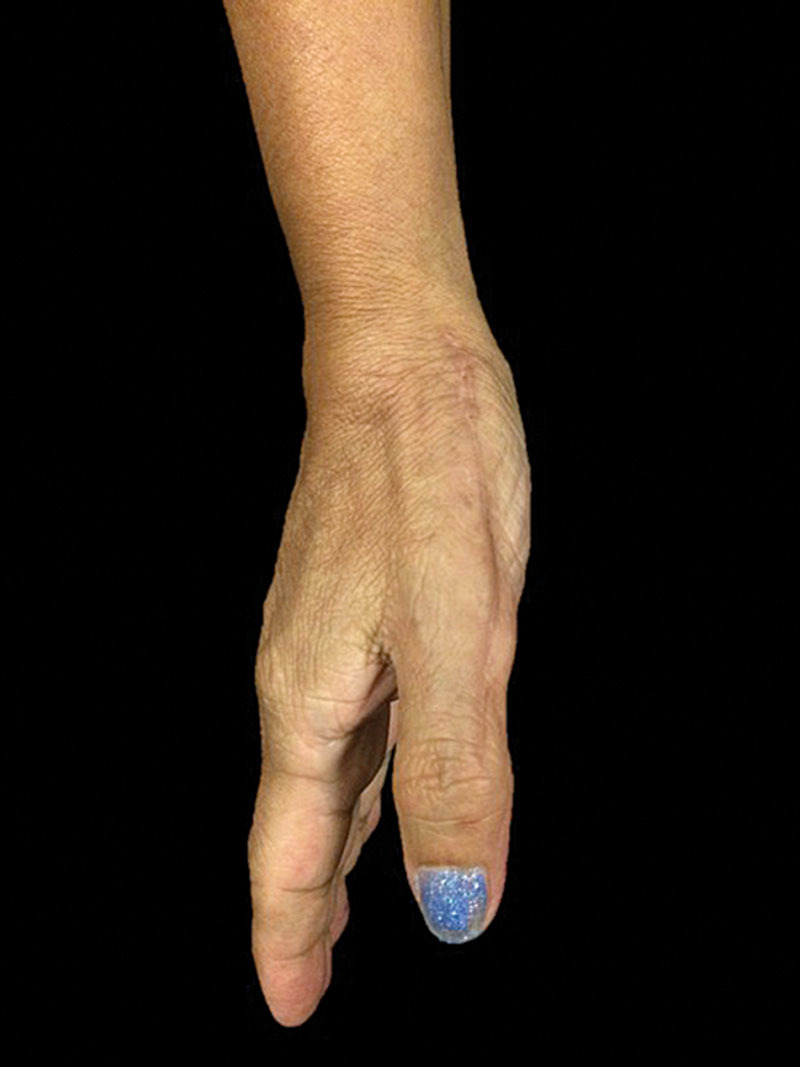

Fig. 2.

View of thumb 9 months postoperatively.

DISCUSSION

GCTB of the hand is a rare, aggressive subset of GCTB with advanced bone destruction and frequent involvement of articular cartilage. Because of its aggressive nature, it is recommended to make a wide excision to attain negative margins and minimize rates of recurrence and/or pulmonary metastasis.15 Isolated curettage has a reported recurrence rate of 72%, whereas amputation has a recurrence rate of 10%.16 To minimize recurrence or metastasis and maximize preservation of function, the popular option for GCTB of metacarpal is en bloc resection and reconstruction with a nonvascularized fibular graft with a silicone implant.13,17,18 En bloc resection has a relatively low recurrence rate at 15%, allowing for excision of the entire tumor mass while preserving flexion and extension at the MCP joint.16 Other common sites of donor bone grafts include the iliac crest and metatarsal.19–21

The patient discussed had a grade III Campanacci lesion that required, at minimum, en bloc resection. Therefore, we decided on a 2-stage procedure in an attempt to minimize bone loss, while maintaining negative margins. However, a positive distal margin led to complete excision of the patient’s thumb metacarpal during the second stage. Only 2 cases of complete resection of metacarpal have been reported in the literature. Both described complete excision of the fourth metacarpal and reconstruction with a fibular or iliac crest graft and silicone implant with a good range of motion over the MCP joint.1,21 However, no study to date has discussed reconstruction of an entire thumb metacarpal.

Thumb metacarpal reconstruction presents a unique challenge because of the need to preserve opposition, in addition to flexion and extension, at the MCP joint. A silicone MCP arthroplasty was decided against in our case because of the high levels of demands placed on the MCP joint of the thumb. The Silastic joint would not have withstood the radially directed stresses at the MCP joint with normal pinching and grasping motions. Therefore, a bridging, tricortical iliac crest bone graft was the most appropriate option for preservation of the native thumb’s length and function as a stable post for pinching and grasping (Figs. 3, 4).

Fig. 3.

Postoperative photograph of thumb at 11.5 months.

Fig. 4.

Postoperative photograph of thumb at 11.5 months demonstrating opposition of thumb.

The most common site of metastasis after initial surgical treatment is the lung, possibly due to dissemination of tumor cells during surgery. Most GCTB lung metastases are benign, whereas others may spontaneously regress or progress and cause death.22 Continuous follow-up for at least 3 years is essential to prevent undesirable sequelae.

SUMMARY

Giant cell tumor of hand bones is a rare, locally aggressive tumor with a high rate of metastasis. A 2-stage surgical resection and a tricortical iliac bone graft reconstruction for a metacarpal giant cell tumor of the thumb are proposed. The short-term result is very encouraging with respect to both function and absence of recurrence and is awaiting long-term follow-up.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the LSU Health Department of Surgery.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jones NF, Dickinson BP, Hansen SL. Reconstruction of an entire metacarpal and metacarpophalangeal joint using a fibular osteocutaneous free flap and silicone arthroplasty. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unni KK. Dahlin’s Bone Tumors: General Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases. Lippincott-Raven; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campanacci M, Baldini N, Boriani S, et al. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:106–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werner M. Giant cell tumour of bone: morphological, biological and histogenetical aspects. Int Orthop. 2006;30:484–489. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Averill RM, Smith RJ, Campbell CJ. Giant-cell tumors of the bones of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1980;5:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(80)80042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minhas MS, Mehboob G, Ansari I. Giant cell tumours in hand bones. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2010;20:460–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biscaglia R, Bacchini P, Bertoni F. Giant cell tumor of the bones of the hand and foot. Cancer. 2000;88:2022–2032. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000501)88:9<2022::aid-cncr6>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huvos AG. Bone Tumors: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis. Saunders; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mirra JM, Picci P, Gold RH. Bone Tumors: Clinical, Radiologic, and Pathologic Correlations. Lea and Febiger; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muheremu A, Niu X. Pulmonary metastasis of giant cell tumor of bones. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:261. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackley HR, Wunder JS, Davis AM, et al. Treatment of giant-cell tumors of long bones with curettage and bone-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:811–820. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199906000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanerkin NG. Malignancy, aggressiveness, and recurrence in giant cell tumor of bone. Cancer. 1980;46:1641–1649. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19801001)46:7<1641::aid-cncr2820460725>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Athanasian EA, Bishop AT, Amadio PC. Autogenous fibular graft and silicone implant arthroplasty following resection of giant cell tumor of the metacarpal: a report of two cases. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22:504–507. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(97)80020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldenberg RR, Campbell CJ, Bonfiglio M. Giant-cell tumor of bone. An analysis of two hundred and eighteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52:619–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel MR, Desai SS, Gordon SL, et al. Management of skeletal giant cell tumors of the phalanges of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1987;12:70–77. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(87)80163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliveira VC, van der Heijden L, van der Geest IC, et al. Giant cell tumours of the small bones of the hands and feet: long-term results of 30 patients and a systematic literature review. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B:838–845. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B6.30876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manfrini M, Stagni C, Ceruso M, et al. Fibular autograft and silicone implant arthroplasty following resection of giant cell tumor of the metacarpal: a case report with 8 years follow-up. Orthopedics. 2008;31:96. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20080101-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ropars M, Kaila R, Cannon SR, et al. Primary giant cell tumours of the digital bones of the hand. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2007;32:160–164. doi: 10.1016/J.JHSB.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose EH. Reconstruction of central metacarpal ray defects of the hand with a free vascularized double metatarsal and metatarsophalangeal joint transfer. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9A:28–31. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinaldi E. Metacarpal loss treated by metatarsal substitution. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1976;2:335–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlow SB, Khuri SM. Metacarpal resection with a contoured iliac bone graft and silicone rubber implant for metacarpal giant cell tumor: a case report. J Hand Surg Am. 1985;10:275–278. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(85)80121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naam NH, Jones SL, Floyd J, et al. Multicentric giant cell tumor of the fourth and fifth metacarpals with lung metastases. Hand (N Y) 2014;9:389–392. doi: 10.1007/s11552-013-9574-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]