Summary:

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are the most common benign pediatric soft-tissue tumors. Ulceration—the most frequent complication of IH—tends to heal poorly and is associated with pain, bleeding, infection, and scarring. Mainstay treatment modalities include propranolol (β-blocker) and corticosteroids, whose effectiveness is countered by a need for long-term medication and risk of systemic adverse effects and ulcer recurrence. A 3-month-old infant presented to us with a large, medial thigh-ulcerated IH that progressed despite 2 prior months of dressings and topical antimicrobials. Topical timolol 0.5% thrice daily was initiated, and significant healing was evident at 1 week, with complete healing at 1 month. Timolol was stopped after 3 months, and at 18 months after cessation of timolol, there was no ulcer recurrence. This novel therapy for ulcerated IH seems to have many advantages such as rapid efficacy with easy application, no systemic adverse effects and no long-term recurrence, and current literature describing similar advantages justifies the use of this treatment modality in infants.

Infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are the most common benign soft-tissue tumors in children. Most IHs involute spontaneously after initial proliferation and need no intervention unless complication arises. Ulceration is the most frequent complication of IH. Ulcerated IHs often heal poorly despite wound care, causing pain, bleeding, infection, sleep and feeding interference, and disfiguring scarring. Complicated IHs have been treated with propranolol (β-blocker) and corticosteroids, whose effectiveness is countered by need for long-term medication, risks of myriad systemic adverse effects, and recurrence after stopping medication.1 We successfully used a topical β-blocker—timolol—to heal a large ulcerated IH swiftly without adverse effects and recurrence and performed an extensive literature review to validate the effectiveness of topical β-blockers for ulcerated IH.

CASE REPORT

A 3-month-old infant presented to us with a 50-mm × 50-mm left medial thigh superficial protuberant IH that appeared at birth growing steadily over time and then gradually developed 35-mm × 35-mm ulceration of the superior half over the last 6 weeks (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A, Left thigh hemangioma (50 mm × 50 mm) with superior-half ulceration (35 mm × 35 mm) in a 5-month-old child, progressing despite 2 months of topical antimicrobial initiation and before timolol initiation. B, Ulceration clearly starting to heal and contract after just 1 week of application of 2 drops of 0.5% topical timolol thrice daily. C, Complete healing after 1 month of timolol, leaving behind a whitish telangiectasic scar.

The ulcer was treated with 0.5% neomycin ointment twice daily for 1 month and then with 1% silver sulfadiazine cream twice daily for the subsequent month—all had no effect on ulcer healing. At 5 months of age, 2 drops of 0.5% timolol solution was applied thrice daily over the entire lesion, with hydrocolloid secondary dressing. With that the ulcer started contracting in the first week, and complete healing was achieved by 1 month, leaving a whitish scar (Fig. 1). Caregivers reported no signs of pain during dressing changes. At biweekly outpatient clinic reviews, the child’s recorded vital signs ranged as follows: heart rate, 125–142 beats per minute; blood pressure, 75–88/48–60 mmHg; and random glucose, 5.4–8.0 mmol/L. Timolol was continued for 3 months, and there was no ulcer recurrence at 18 months after stopping treatment.

DISCUSSION

IH is the most common pediatric benign soft-tissue tumor, characteristically proliferating in the first year of life followed by spontaneous involution over months or years, making intervention mostly unnecessary.2 Therapy is indicated for life-threatening or functional complications (obstruction of airway or vision, or oral, nasal, auditory orifices; bleeding), permanent disfigurement, ulceration, minimizing psychosocial stress and avoiding potentially scarring surgery.3

The most common complication of IH is ulceration as in our patient, occurring in up to 16% of patients at about 2–3 months after birth but sometimes as early as the neonatal period.4 Ulceration is more common in centrofacial and perineum regions and may be heralded by surfacing of blackish spots or white discoloration. Ulcerated IHs tend to be larger than nonulcerated ones, and friction, low birth weight, prematurity, and female gender are risk factors associated with ulceration.5 Ulcerated IHs can be very painful and complicated by secondary infection and bleeding requiring transfusion. Disfiguring scarring follows resolution. Early treatment including appropriate wound care is essential in ulcerated IH to arrest progression and minimize sequelae.

Therapy for complicated IHs is divided into pharmacological treatment, surgery, and laser. Propranolol—shown to be rapidly efficacious for IH in the proliferative phase—has lately supplanted corticosteroids as the first-choice treatment; it arrests IH growth through increased endothelial apoptosis, vasoconstriction of microvessels, and downregulation of angiogenic pathways.3,6,7

Complete healing of ulcerated IH with any regimen typically requires 3 months.8 In ulcerated IH, propranolol is found to minimize delayed ulcer healing (taking 4–8.7 weeks) and pain.1,9 Increased hypoxia induces ulceration in IH, and β-blockers act against hypoxia via the hypoxia-inducible factor pathway, accounting partly for their ulcer-healing ability.5 Systemic propranolol (2–3 mg/kg/d divided twice daily or thrice daily for 6–9 months in ulceration), however, risks many side effects: bradycardia, hypotension, hypoglycemia, gastrointestinal discomfort/reflux, fatigue, and bronchospasm.1,4 Intralesional propranolol is also effective but like intralesional corticosteroid requires general anesthesia for pediatric administration; moreover, systemic absorption remains a concern in such vascular tumors.10

Propranolol nonresponders may require corticosteroids. Rarely are interferon-α-2a/-2b or vincristine needed, and their effects on ulcerated IH are not well defined. Systemic corticosteroids risk systemic effects of adrenal suppression, growth retardation, and gastritis, and only 72% of ulcerated IH respond.8 Intralesional and topical corticosteroids, with less risk of systemic effects, are more suited for small IH and may cause skin depigmentation, skin and fat atrophy, and necrosis. Topical 0.01% becaplermin gel rapidly healed perineal ulcerated IH in a small series, but its mechanism is tentative and Food and Drug Administration safety concerns exist.11 Excision is reserved for small localized IH, whereas pulsed-dye laser may accelerate healing in superficial ulcerated IH.4

Recent effective topical treatment of IHs has been reported using 0.1%, 0.25%, and 0.5% β-blocker timolol maleate, which works via the same mechanism as propranolol.12–16 Topical timolol is advantageous for its availability, low cost, easy administration, and minimal risk of adverse effects.16 Applying timolol 0.5% to the skin and ulcer is safe because peak plasma concentrations even after ocular administration are very low, suggesting minimal systemic absorption.17

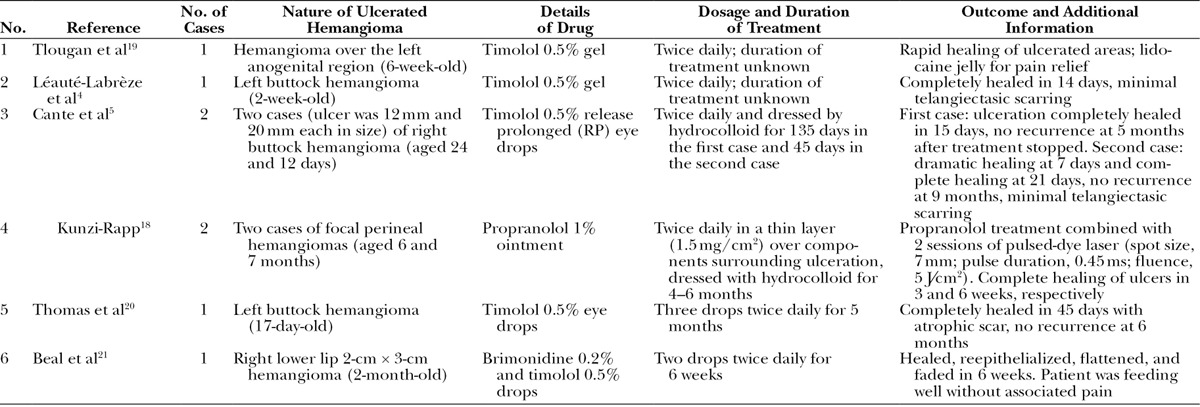

To the best of our knowledge, there have been 8 reported cases of localized ulcerated IH successfully treated with topical β-blocker (Table 1).4,5,18–21 Average age of these children at initiation of therapy was 2.3 months (range, 0.4–7 months). Dimensions of the widest ulceration ranged from 12 to 50 mm. Except for 1 study using propranolol, all used some formulation of timolol 0.5% twice daily and duration of treatment ranged from 1.5 to 6 months. Like in our patient, all reported fast onset of healing within a week and complete healing by 2 weeks to 1.5 months, with no adverse effects, comparing favorably with systemic propranolol. Propranolol ointment and pulsed-dye laser were combined in Kunzi-Rapps’s18 study, but propranolol ointment certainly played a major role considering the rapid healing in 3 and 6 weeks.

Table 1.

Reported Cases of Ulcerated Hemangioma Treated with Topical β-Blocker

Twelve percent of ulcerated IH cases treated with propranolol experienced ulcer recurrence after stopping treatment.1 However, the reported cases of ulcerated IH treated with topical β-blocker had no recurrence at up to 18 months follow-up after therapy cessation, including our patient. Our patient appeared pain-free during timolol dressing changes, and Beal et al21 found that their patient with ulcerated lip IH could feed well after brimonidine–timolol application, suggesting topical β-blockers minimize ulcer-pain like propranolol.

Although randomized controlled trials are desired to elucidate the efficacy, optimal formulation, vehicle and dosage, analgesia, and long-term outcome of topical β-blocker as a primary therapy for ulcerated IH, it seems generally safe and effective even if administered at an early age, with the advntages of easy application with fast onset of action, swift healing without adverse effects and no ulcer recurrence in the long term. From our positive experience and current evidence, we advocate considering the early use of topical timolol 0.5% as a first-line treatment for ulcerated IH.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saint-Jean M, Léauté-Labrèze C, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al. Groupe de Recherche Clinique en Dermatologie Pédiatrique. Propranolol for treatment of ulcerated infantile hemangiomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holland KE, Drolet BA. Infantile hemangioma. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:1069–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frieden IJ, Eichenfield LF, Esterly NB, et al. Guidelines of care for hemangiomas of infancy. American Academy of Dermatology Guidelines/Outcomes Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:631–637. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Léauté-Labrèze C, Prey S, Ezzedine K. Infantile haemangioma: part II. Risks, complications and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1254–1260. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cante V, Pham-Ledard A, Imbert E, et al. First report of topical timolol treatment in primarily ulcerated perineal haemangioma. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97:F155–F156. doi: 10.1136/fetalneonatal-2011-301317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Storch CH, Hoeger PH. Propranolol for infantile haemangiomas: insights into the molecular mechanisms of action. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:269–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Izadpanah A, Izadpanah A, Kanevsky J, et al. Propranolol versus corticosteroids in the treatment of infantile hemangioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:601–613. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31827c6fab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HJ, Colombo M, Frieden IJ. Ulcerated hemangiomas: clinical characteristics and response to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:962–972. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.112382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermans DJ, van Beynum IM, Schultze Kool LJ, et al. Propranolol, a very promising treatment for ulceration in infantile hemangiomas: a study of 20 cases with matched historical controls. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:833–838. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Awadein A, Fakhry MA. Evaluation of intralesional propranolol for periocular capillary hemangioma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:1135–1140. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S22909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frieden IJ. Addendum: commentary on becaplermin gel (Regranex) for hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:590. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00781_3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo S, Ni N. Topical treatment for capillary hemangioma of the eyelid using beta-blocker solution. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:255–256. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ni NBA, Langer PMD, Wagner RMD, et al. Topical timolol for periocular hemangioma: report of further study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:377–379. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pope E, Chakkittakandiyil A. Topical timolol gel for infantile hemangiomas: a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:564–565. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chambers CB, Katowitz WR, Katowitz JA, et al. A controlled study of topical 0.25% timolol maleate gel for the treatment of cutaneous infantile capillary hemangiomas. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;28:103–106. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31823bfffb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakkittakandiyil A, Phillips R, Frieden IJ, et al. Timolol maleate 0.5% or 0.1% gel-forming solution for infantile hemangiomas: a retrospective, multicenter, cohort study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:28–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shedden AH, Laurence J, Barrish A, et al. Plasma timolol concentrations of timolol maleate: timolol gel-forming solution (TIMOPTIC-XE) once daily versus timolol maleate ophthalmic solution twice daily. Doc Ophthalmol. 2001;103:73–79. doi: 10.1023/a:1017962731813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunzi-Rapp K. Topical propranolol therapy for infantile hemangiomas. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:154–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tlougan BE, Gonzalez ME, Orlow SJ. Abortive segmental perineal hemangioma. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas J, Kumar P, Kumar DD. Ulcerated infantile haemangioma of buttock successfully treated with topical timolol. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:168–169. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.118432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beal BT, Chu MB, Siegfried EC. Ulcerated infantile hemangioma: novel treatment with topical brimonidine–timolol. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:754–756. doi: 10.1111/pde.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]