Abstract

Recent studies have suggested that Helicobacter pylori could prevent allergic disease, particularly in children. However, whether this is true in adults is controversial. The aim of this study was to investigate whether there is negative association between H. pylori infection and asthma among adults in an area with a high prevalence of H. pylori.

This was a cross-sectional study using 2011 health surveillance data. Blood samples were taken from all participants to measure serum H. pylori IgG status. Information on demographics, socioeconomic status, and medical history, including asthma and other allergic conditions were collected by a questionnaire.

Of the 15,032 patients, 9492 (63.1%) had a history of H. pylori infection, 359 (2.4%) had asthma, and 3277 (21.8%) had other allergic conditions. H. pylori infection was positively correlated with age (OR, 1.050; 95% CI, 1.047–1.053, P < 0.001). Asthma history was positively correlated with age (OR, 1.022; 95% CI, 1.013–1.032, P < 0.001). H. pylori and age were shown to have interaction on asthma in the total participants (OR, 1.041; 95% CI, 1.021–1.062, P < 0.001). In subgroup analysis, H. pylori infection among those < 40 years old was inversely correlated with asthma (OR, 0.503; 95% CI, 0.280–0.904, P = 0.021). Other allergic conditions were not related with H. pylori infection among the total and those <40 years old.

The inverse association between H. pylori infection and asthma among young adults suggests that the underlying immune mechanism induced by H. pylori infection may affect allergic reactions associated with asthma in young adults.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative spiral bacterium that colonizes the gastric epithelium causing chronic gastritis and peptic ulcer disease.1 It has also been classified as a group 1 gastric cancer carcinogen by the International Agency of Research on Cancer.2 Thus, enormous efforts have been made to develop better diagnostic tools and treatment regimens to eradicate H. pylori. As a result, the prevalence of H. pylori appears to be decreasing in many parts of the world.3–8 Possible contributors to this decrease are assumed to be improved sanitation, widespread use of antibiotics, and decreased family size.9 In contrast, the prevalence of allergic diseases, such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis, has increased dramatically in developed countries.10–12 This rapid increase could be explained by declining exposure to infection because of smaller sized families, improved hygiene, and vaccination programs.13,14 In addition, changes in indigenous microflora have been suggested to play a role in the rise in allergic diseases.15 Some studies have found an inverse association between H. pylori infection and the occurrence of asthma, particularly in children.5,16,17 However, whether it is also true in adults is controversial. Moreover, no East Asian studies have revealed any relationship between H. pylori and asthma, although this region has the highest prevalence of H. pylori. This study was performed to investigate whether there is negative association between H. pylori and asthma among adults in an area with a high prevalence of H. pylori infection.

METHODS

Study Population

This study enrolled all Korean subjects aged ≥18 years who had health surveillance checkups, including the serum anti-H. pylori IgG level at the Seoul National University Hospital Healthcare System Gangnam Center between January and December 2011. For each subject, the body mass index was calculated with body weight and height which were measured on the day of health checkup. All subjects answered a questionnaire under the supervision of a well-trained interviewer. We retrospectively reviewed prospectively collected questionnaires for this study. The questionnaire included questions about demographic characteristics (age, sex, and residence), socioeconomic status (education level and monthly family income), and clinical characteristics (smoking history, H. pylori eradication history, current medication, history of asthma, and other allergic conditions). In this study, H. pylori eradication history was defined as any history of medication intended to eradicate H. pylori, regardless of documented clearance. Other allergic conditions consisted of allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, chronic urticaria, food/drug allergies, contact dermatitis, and bee venom allergy. No participants reported anaphylaxis.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. H-1506-002-6730) and complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient informed consent was waived given the retrospective nature of the study.

H. pylori Infection Status

H. pylori infection was defined as having anti-H. pylori IgG or a history of H. pylori eradication. Anti-H. pylori IgG was measured using H. pylori-EIA-Well (Radim, Rome, Italy).7 The sensitivity and specificity of this kit have been shown to be 95.6% and 97.8%, respectively, compared with Genedia H. pylori ELISA used as the gold standard in a previous study. Genedia H. pylori ELISA using all known antigens from Korean H. pylori strains has shown 97.8% of sensitivity and 92.0% of specificity.18H. pylori eradication history was investigated by a questionnaire. To enhance the data on H. pylori infection history, we reviewed the serological status in 2005 when available.19 Out of the total study population, 8.5% had serological test in 2005 through the health checkup. Overall serological status was considered positive when either anti-H. pylori IgG status in 2005 or 2011 was positive. Those who had either anti-H. pylori IgG or a history of H. pylori eradication were considered to have a current or past H. pylori infection.

History of Asthma and Other Allergic Conditions

The questionnaires completed at the time of medical checkups and their medical records were reviewed to collect information about patient's history of asthma and other allergic conditions. Those who had been diagnosed with asthma by a physician, regardless of current medication, were considered to have asthma.

Medical records or current medication were checked in more detail in the case of inconsistency of multiple answers for asthma history, and when there were definite records for an asthma diagnosis or the patient was currently taking a bronchodilator prescribed for asthma, the subjects were considered to have asthma. Other allergic conditions were considered positive when any one of the answers was positive among the multiple questionnaires.

Socioeconomic Status

Education status was categorized into 3 levels of low (middle school graduate or less), middle (high school graduate or university dropout), and high (graduate of university or postgraduate course). Monthly family income status was classified into 3 groups of low (<$3000USD/month), middle ($3000–10,000/month), and high (>$10,000/month). The income category was taken from the previous study concerning H. pylori prevalence in Korea.7

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Basically we used the chi-square test. However, Fisher's exact test was used instead of chi-square test when >20% of expected frequencies were 5 or less. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student's t-test. The binary logistic regression model was used to analyze dichotomous variables according to predictor variables. Independent variables with P values <0.20 in univariate analyses and those already known to be strongly associated with the outcome variable were examined in multivariable binary logistic regression models. A P value <0.05 was considered significant. All P values are presented without correction for multiple testing. All analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, ver. 18.0 for Windows software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

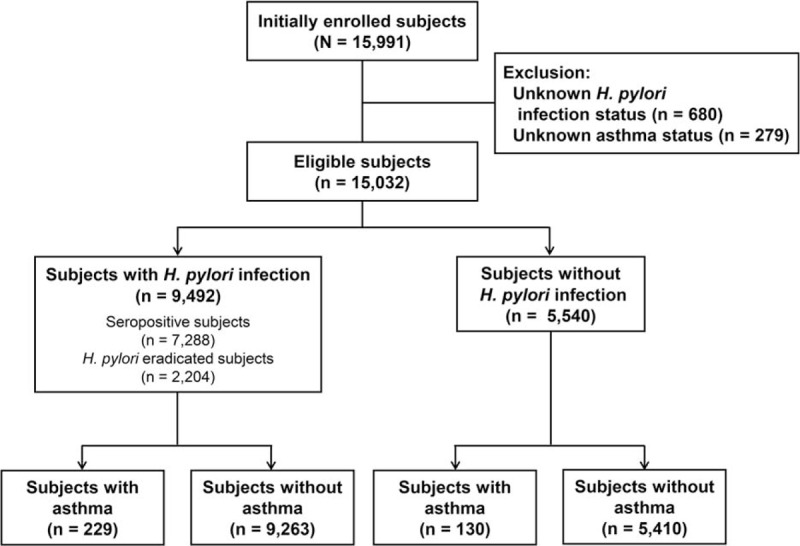

Figure 1 shows the participant flow diagram. Among the 15,991 subjects, H. pylori infection status and history of asthma were unknown in 680 and 279 subjects, respectively. Among the remaining 15,032 eligible subjects, 7288 (48.5%) were seropositive for anti-H. pylori IgG and 2204 (14.7%) reported a history of H. pylori eradication therapy. Taken together, 9492 (63.1%) had H. pylori infection. A history of asthma was reported in 229 (2.4%), and 130 (2.3%) among those with and without H. pylori infection, respectively. Allergic conditions other than asthma were reported in 3277 (21.8%).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic flowchart for subjects enrolled in this study. A total of 15,032 subjects who had health checkup were included in this study.

Demographic Characteristics

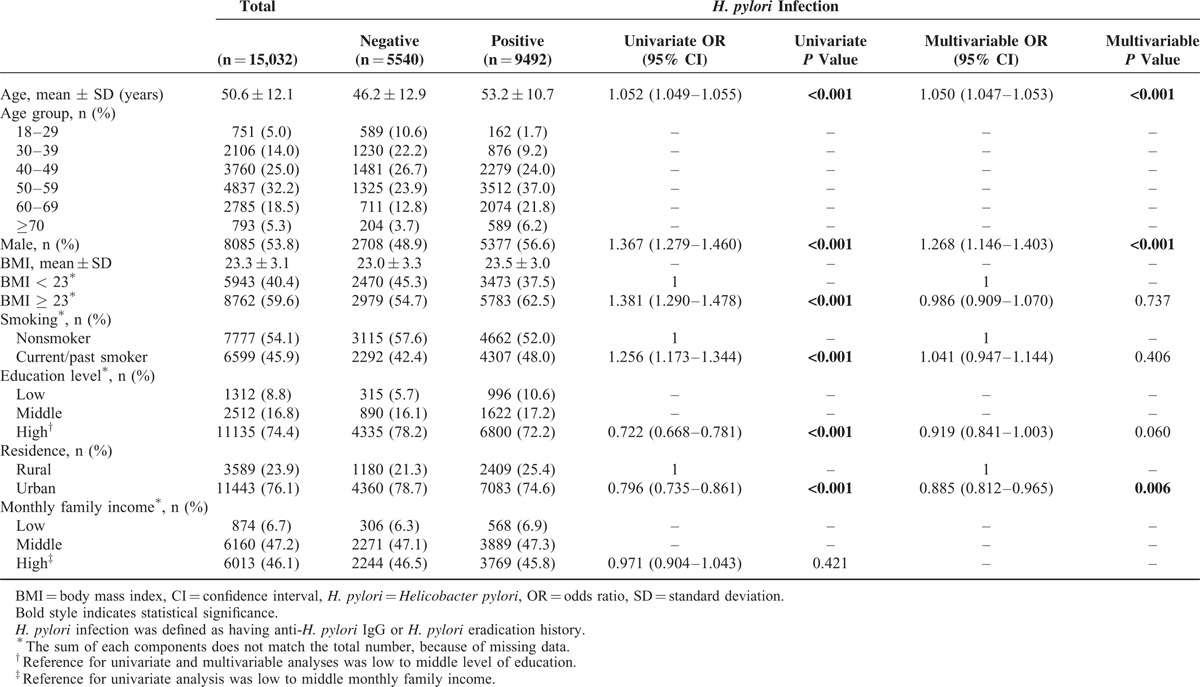

Overall, mean age was 50.6 years and the proportion of men was 53.8%. About half of the subjects were past or current smokers. More than 70% had a high education level and were living in an urban area. Most of the subjects had monthly family incomes >$3000 (Table 1). A multivariable regression indicated that subjects with H. pylori infection were older (P < 0.001) and were more often men (P < 0.001), compared with those without H. pylori infection. In addition, H. pylori infection was positively correlated with age (OR, 1.050; 95% CI, 1.047–1.053, P < 0.001; Figure 2).

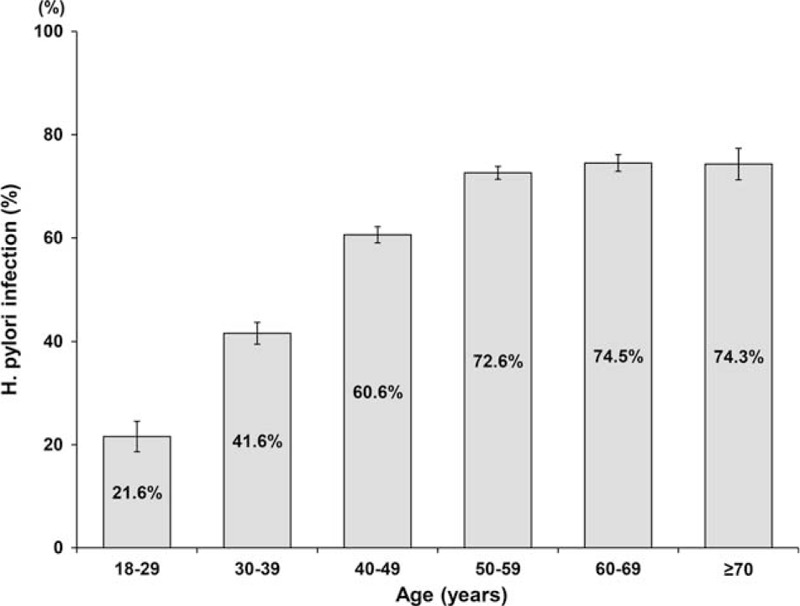

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of H. pylori infection according to age. Prevalence of H. pylori infection based on seroprevalence of anti-H. pylori IgG antibody and the history of H. pylori eradication therapy showed increasing trend along with age. H. pylori = Helicobacter pylori.

Relationship Between H. pylori Infection and Asthma

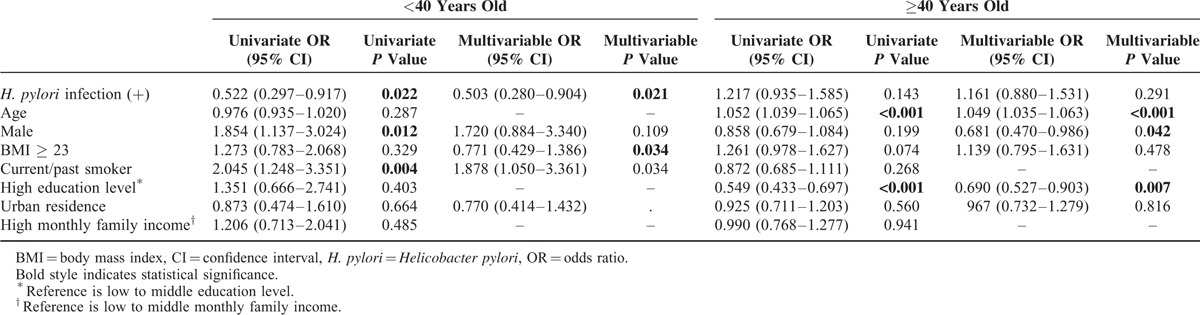

A multivariable analysis showed that H. pylori infection status (P = 0.001) and level of education (P = 0.001) were independently associated with asthma (Table 2). Also, age and H. pylori infection were revealed to have a positive interaction on asthma (P < 0.001).

TABLE 2.

Factors Related With Asthma and Other Allergic Conditions (Logistic Regression)

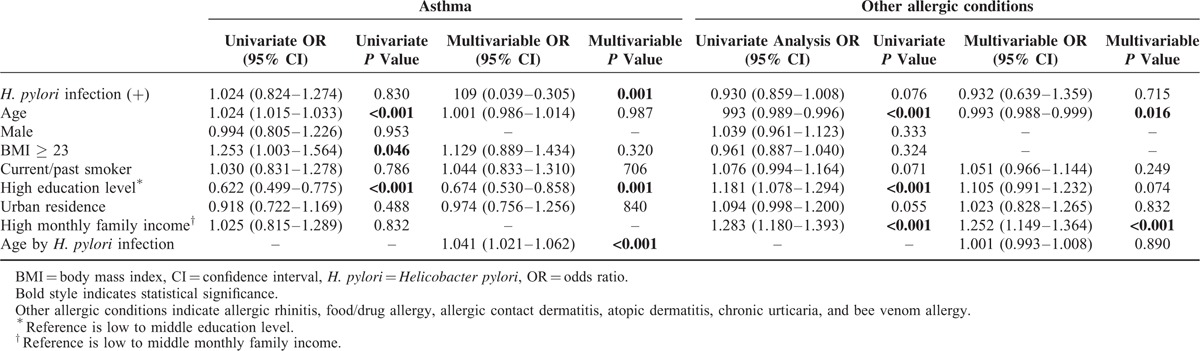

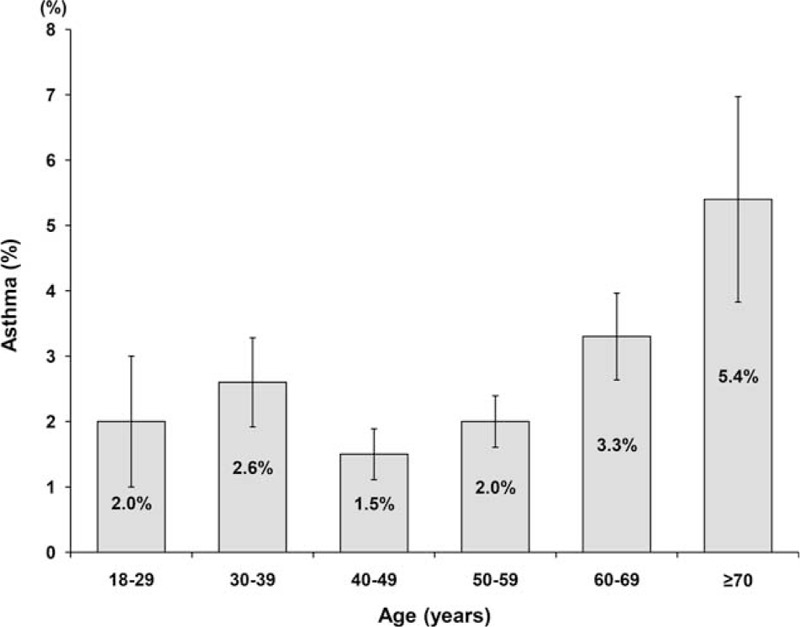

Among all participants, H. pylori infection showed inverse relationship with asthma (OR, 0.109; 95% CI, 0.039–0.305, P < 0.001). However, as the interaction between H. pylori infection and age was also related with asthma with statistical significance, we further performed subgroup analysis by age. In this study population, asthma history was positively correlated with age (OR, 1.022; 95% CI, 1.013–1.032, P < 0.001). However, the increasing tendency with age was only significant among those ≥40 years (OR, 1.052; 95% CI, 1.039–1.065, P < 0.001), but not among those <40 years (OR, 0.978; 95% CI, 0.937–1.022, P = 0.328). As the trend in asthma prevalence according to age shifted before and after the 40s (Figure 3), subgroup analyses with cut-off value of 40 years were performed to analyze the relationship between H. pylori infection and asthma (Table 3). A univariate analysis revealed that H. pylori infection was significantly inversely correlated with asthma among those <40 years (OR, 0.522; 95% CI, 0.297–0.917, P = 0.022), whereas this was not observed among those ≥40 years (OR, 1.217; 95% CI, 0.935–1.585, P = 0.143). Next, factors related to asthma were evaluated among those <40 years. In this subgroup, male sex (OR, 1.854; 95% CI, 1.137–3.024, P = 0.012) and current/past smoking (OR, 2.045; 95% CI, 1.248–3.351, P = 0.004) were significantly associated with asthma, whereas age, body mass index ≥23 kg/m2, high education level, urban residence, high monthly family income were not. H. pylori infection was negatively correlated with asthma after adjusting for factors shown to be related with asthma among those <40 years in a univariate analysis (OR, 0.503; 95% CI, 0.280–0.904, P = 0.021).

FIGURE 3.

Prevalence of asthma according to age. The trend of asthma prevalence according to age significantly shifted before and after forties. It tended to decrease by age in the population under their 40s and since then gradually increased by age.

TABLE 3.

Factors Related With Asthma According to Age Groups (Multivariable Logistic Regression)

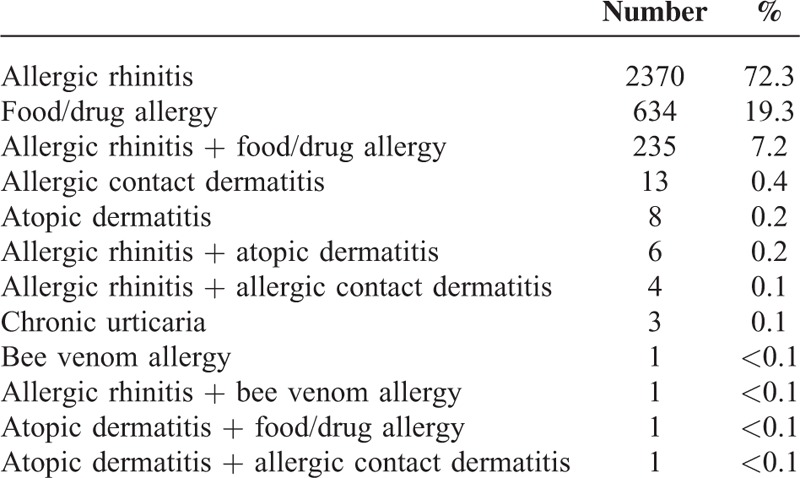

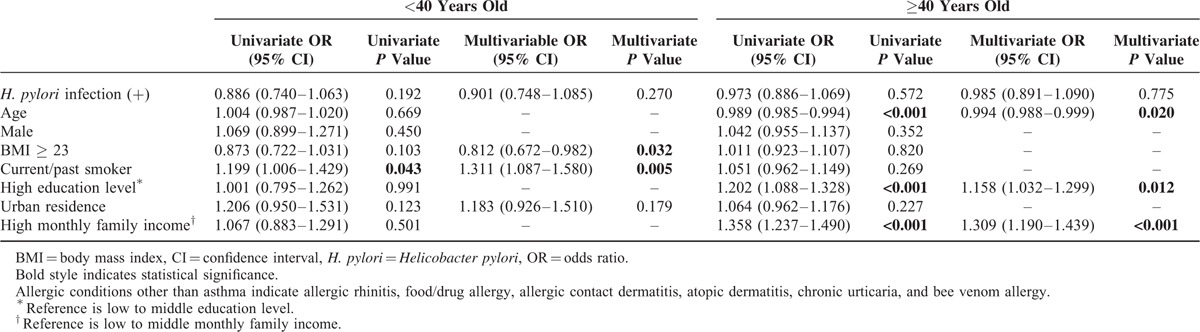

Relationship Between H. pylori Infection and Allergic Conditions Other than Asthma

Most of the allergic conditions other than asthma were allergic rhinitis with a rate of 79.8%, followed by food/drug allergy with a rate of 26.5%. The types of allergic conditions other than asthma and their combinations are shown in Table 4. H. pylori infection showed no relationship with other allergic conditions in a univariate analysis (OR, 0.930; 95% CI, 0.859–1.008, P = 0.076). A multivariable analysis revealed that H. pylori infection was not an independent predictor for other allergic conditions (OR, 0.932; 95% CI, 0.639–1.359, P = 0.715) (Table 2). In contrast, age (OR, 0.993; 95% CI, 0.993–0.999, P = 0.016) and high education level (OR, 1.252; 95% CI, 1.149–1.364, P < 0.001) were independently related with other allergic conditions. In subgroup analyses among those less than and greater than 40 years old, H. pylori infection was not significantly related with other allergic conditions in both univariate and multivariable analyses (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Types of Allergic Conditions Other than Asthma

TABLE 5.

Multivariable Analysis for Factors Related With Allergic Conditions Other than Asthma According to Age Groups

DISCUSSION

This large scale study demonstrated an inverse relationship between H. pylori infection and asthma among adults <40 years old. A similar inverse relationship has been reported among children in several studies,5,16,17 but it remains still controversial in adults due to conflicting evidence.20–24 Even in studies showing an inverse relationship in the adult population, the relationship is only true for CagA+ H. pylori strains.22,23 In addition, most studies that have shown an inverse relationship between H. pylori and asthma have been conducted in Western countries where H. pylori prevalence is considerably low. Studies performed in East Asia have failed to show a relationship between them,20,21 where subgroup analyses were not performed according to age. We found inverse association between H. pylori infection and asthma among adult individuals. According to age groups, the inverse correlation was clear in those <40 years old. This is the first report to show an inverse relationship between H. pylori infection and asthma among adults in an area with a high prevalence of H. pylori.

The present study included a large number of healthy individuals. Age ranged from 18 to 91 years, and mean age was 50.6 years. The tendency for H. pylori infection increased with age, which is consistent with a nationwide study on H. pylori prevalence that showed a birth cohort effect.7 However, the asthma prevalence rate, which did not show increasing tendency with age in the younger population, changed significantly in subjects in their 40s and then increased with age. Nationwide surveys conducted in Korea show that the prevalence of asthma in 12 to 15 year-old Korean children almost doubled between 1995 and 2000, indicating an increasing asthma trend in adolescence.12,25 A population-based study using questionnaires on current wheezing and methacholine challenge tests in Korean adults showed that the prevalence of asthma was positively correlated with age, particularly in subjects >40 years old.26 The 2010 Korean National Health and Nutrition survey showed similar findings that the prevalence of physician-diagnosed asthma decreases until the age of 40 and then increases again.27 Considering these results and an expected cohort effect, the trend in asthma prevalence shown in the present study seems comparable with that of the general Korean population. In addition, a similar asthma prevalence curve by age was reported by the National Health Interview Survey of United States using 2001 to 2009 annual averages.28 Thus, we divided patients with asthma into elderly and youth types, at 40 years of age based on the age at the time of participation in this study. It was carried out under the concept that early onset asthma has different characteristics and mechanism of development from those of late onset asthma, which has been suggested in previous studies.22,29 Similar to findings reported previously in a Western country,22 our study showed an inverse relationship in young adults but not in older adults. However, the confidence interval for the association among the young adults was considerably wide in this study. It is thought to be because of the relatively small number of asthmatics in this group. Nevertheless, the finding that the association in the young adults was true even after adjusting for related parameters further enhances the relationship. Therefore, the absence of H. pylori infection was an independent risk factor for asthma in young adults. This study's result also shows that the inverse relationship between H. pylori and asthma is not exclusively Western but could be a worldwide phenomenon.

Our findings could be explained by the “hygiene hypothesis,” which proposes that increased exposure to microbes early in life may prevent allergic diseases.30 In this context, several studies have reported inverse relationships between asthma and several micro-organisms, such as hepatitis A virus, Toxoplasma gondii, and herpes simplex virus type 1.31 Another study showed a dose response in an inverse relationship between atopy and multiple infection of foodborne or orofecal microbes.32H. pylori could be only a surrogate for hygiene status and co-infection with organisms that are true asthma preventive factors. However, H. pylori has demonstrated definite relationships with asthma after adjusting for other micro-organisms,5,22 showing a specific association with asthma. Another hypothesis supporting this inverse association is the “decreasing microbiota hypothesis,” which claims that intestinal microbiota affect the immune system.33 According to this hypothesis, commensal bacteria regulate the Th1/Th2 equilibrium. H. pylori, the ancient indigenous microbe, is expected to affect the immune system by shifting the cytokine balance toward the Th1 type, which suppresses Th2-dominated allergic diseases.34 It has been reported that H. pylori alters the T cell response by inducing T cell expression of interleukin-12, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interferon-γ.35–37 In addition, induction of regulatory T cells has been verified through H. pylori infection in several studies.38–42 In addition, H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein was reported to play an important role in promoting the HkTh1 immune response, which consequently represses asthma development.43,44 Another study reported that oral tolerization with H. pylori extract prevents airway hyper-responsiveness, bronchoalveolar eosinophilia, pulmonary inflammation, and Th2 cytokine production, which are hallmarks of allergen-induced asthma in mice.45

In this study, the inverse relationship between H. pylori and asthma was found in those <40 years, but not in those >40 years old. The reason for this is unclear. However, it may be related to the different characteristics of early and late onset asthma. Early onset asthma usually accompanies atopic dermatitis or allergic rhinitis. Such an allergic march is associated with allergen sensitization and an IgE-mediated Th2 reaction. In contrast, late onset asthma can be affected by various environmental factors, such as smoking, air pollution, certain occupations, and others,46 so the aetiologic role of H. pylori would be small. In the present study, we did not differentiate between the early and late onset asthma, but divided the subjects based on age at the time of participation, which could be a limiting factor of this cross-sectional study. Actually, asthma in the elderly does not necessarily mean only late onset asthma, but long lasting early onset asthma and recurrent asthma after improvement of early onset asthma as well.47 Thus, it can be very difficult to categorize asthma according to time of onset. In this study, H. pylori infection was not associated with other allergic conditions excluding asthma. The possible reason could be that this category was a cluster of various allergic conditions involving a variety of mechanisms. However, even analysis for allergic rhinitis alone, which accounted for about 80% of the allergic conditions other than asthma, failed to show a relationship with H. pylori. Another possible reason could be the low accuracy of data on these allergic conditions. In the present study, the definition of “asthma” was “physician-diagnosed asthma,” which is quite reliable. However, the definition for “allergic rhinitis” and “food/drug allergy” mostly depended on a subject's report rather than a physician-diagnosed. For example, subjects with vasomotor rhinitis that shows symptoms, similar to those observed in subjects with allergic rhinitis, on the exposure of cold air could have reported that they had allergic rhinitis.48 Another explanation is that it might be an outcome not associated with an allergic etiology. The relationship between H. pylori and allergic rhinitis has not been consistently demonstrated to be inverse.16,24 Therefore, H. pylori may affect allergic rhinitis differently way from asthma. A well-designed prospective study would answer this question.

Several limitations of this study should be mentioned. One is the cross-sectional study design. As we only checked the history of asthma, we could not exclude the possibility of the development of asthma before H. pylori infection. However, as H. pylori acquisition is known to occur in the early life, the development of asthma was presumed to be the later event in the present study. Furthermore, as this study was based on a convenience sample, it inevitably has limitation in representing general population. However, the scale of this study, which is the largest to date on this issue, may have power to better represent the real phenomenon, although not enough as prospective studies do. Besides, the study population of health examinees in this study may not represent the general population. Most of the subjects were highly educated and living in an urban area. This might have induced selection bias. However, after adjusting for those factors, H. pylori infection was inversely related with asthma. Recall bias may have occurred, as our data on asthma history depended on self-report. Nevertheless, we reviewed all available questionnaires obtained during previous years and medical records were reviewed in cases with inconsistent answers about asthma history. Most of the subjects had undergone multiple health checkups at a single center, which enhanced the reliability of the data. Similarly, data on H. pylori infection status was supplemented with H. pylori eradication history, as serological status can shift from positive to negative long time after eradicating H. pylori. Thereby we were able to clearly figure out the history of H. pylori infection rather than current infection, even though there was a possibility of recall bias. Another limitation is that our results give no clue on causality, but only an association due to the nature of cross-sectional study.

Our results indicate that H. pylori infection is inversely related with asthma in young adults. This result suggests that H. pylori infection may inhibit development of asthma in some way in young adults. Therefore, we recommend careful consideration on whether to eradicate H. pylori in young patients with asthma risk factors, as H. pylori may play a role in reducing the risk for asthma. Further prospective studies are warranted to clarify the underlying mechanisms.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index, CI = confidence interval, H. pylori = Helicobacter pylori, OR = odds ratio.

Ethical approval: this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. H-1506-002-6730) and complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding: this work was supported by National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea grant for the Global Core Research Center (GCRC) funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. 2011-0030001).

All the researchers declare independence from funders.

Authors’ contributions: JHL, NK—study conception and design, data analysis/interpretation; JHL—manuscript drafting; SHL, JWK, CMS, YSC, JSK, HCJ, SHC—critical revision of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

STROBE statement: All the items included in STROBE checklist were checked.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Imrie C, Rowland M, Bourke B, et al. Is Helicobacter pylori infection in childhood a risk factor for gastric cancer? Pediatrics 2001; 107:373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Møller H, Heseltine E, Vainio H. Working group report on schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. Int J Cancer 1995; 60:587–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banatvala N, Mayo K, Megraud F, et al. The cohort effect and Helicobacter pylori. J Infect Dis 1993; 168:219–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roosendaal R, Kuipers EJ, Buitenwerf J, et al. Helicobacter pylori and the birth cohort effect: evidence of a continuous decrease of infection rates in childhood. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92:1480–1482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori colonization is inversely associated with childhood asthma. J Infect Dis 2008; 198:553–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.den Hoed CM, Vila AJ, Holster IL, et al. Helicobacter pylori and the birth cohort effect: evidence for stabilized colonization rates in childhood. Helicobacter 2011; 16:405–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim SH, Kwon JW, Kim N, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: nationwide multicenter study over 13 years. BMC Gastroenterol 2013; 13:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirayama Y, Kawai T, Otaki J, et al. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection with healthy subjects in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 29:16–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCaig LF, Besser RE, Hughes JM. Trends in antimicrobial prescribing rates for children and adolescents. JAMA 2002; 287:3096–3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson HR. Prevalence of asthma. BMJ 2005; 330:1037–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eder W, Ege MJ, von Mutius E. The asthma epidemic. N Engl J Med 2006; 3551:2226–2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song WJ, Kang MG, Chang YS, et al. Epidemiology of adult asthma in Asia: toward a better understanding. Asia Pac Allergy 2014; 4:75–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ 1989; 299:1259–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matricardi PM, Rosmini F, Ferrigno L, et al. Cross sectional retrospective study of prevalence of atopy among Italian military students with antibodies against hepatitis A virus. BMJ 1997; 314:999–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blaser MJ, Falkow S. What are the consequences of the disappearing human microbiota? Nat Rev Microbiol 2009; 7:887–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amberbir A, Medhin G, Erku W, et al. Effects of Helicobacter pylori, geohelminth infection and selected commensal bacteria on the risk of allergic disease and sensitization in 3-year-old Ethiopian children. Clin Exp Allergy 2011; 41:1422–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zevit N, Balicer RD, Cohen HA, et al. Inverse association between Helicobacter pylori and pediatric asthma in a high-prevalence population. Helicobacter 2011; 17:30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SY, Ahn JS, Ha YJ, et al. Serodiagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korean patients using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Immunoassay 1998; 19:251–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yim JY, Kim N, Choi SH, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in South Korea. Helicobacter 2007; 12:333–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsang KW, Lam WK, Chan KN, et al. Helicobacter pylori sero-prevalence in asthma. Respir Med 2000; 94:756–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jun ZJ, Lei Y, Shimizu Y, et al. Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence in patients with mild asthma. Tohoku J Exp Med 2005; 207:287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Inverse associations of Helicobacter pylori with asthma and allergy. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:821–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reibman J, Marmor M, Filner J, et al. Asthma is inversely associated with Helicobacter pylori status in as urban population. PLoS One 2008; 3:e4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fullerton D, Britton JR, Lewis SA, et al. Helicobacter pylori and lung function, asthma, atopy and allergic disease - a population-based cross-sectional study in adults. Int J Epidemiol 2009; 38:419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong SJ, Lee MS, Sohn MH, et al. Self-reported prevalence and risk factors of asthma among Korean adolescents: 5-year follow-up study, 1995-2000. Clin Exp Allergy 2004; 34:1556–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim YK, Kim SH, Tak YJ, et al. High prevalence of current asthma and active smoking effect among the elderly. Clin Exp Allergy 2002; 32:1706–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korean guideline for asthma 2015. The Korean Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Clinical Immunology website. http://www.allergy.or.kr/file/150527_01.pdf. Updated May 27, 2015. Accessed February 10, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Liu X. Asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality: United States, 2005–2009. Natl Health Stat Report 2011; 12:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blaser MJ, Chen Y, Reibman J. Does Helicobacter pylori protect against asthma and allergy? Gut 2008; 57:561–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strachan D. Family size, infection and atopy: the first decade of the ‘hygiene hypothesis’. Thorax 2000; 55:S2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matricardi PM, Rosmini F, Panetta V, et al. Hay fever and asthma in relation to markers of infection in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002; 110:381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matricardi PM, Rosmini F, Riondino S, et al. Exposure to foodborne and orofecal microbes versus airborne viruses in relation to atopy and allergic asthma: epidemiological study. BMJ 2000; 320:412–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLoughlin RM, Mills KH. Influence of gastrointestinal commensal bacteria on the immune responses that mediate allergy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127:1097–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amedei A, Cappon A, Codolo G, et al. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori promotes Th1 immune responses. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:1092–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guiney DG, Hasegawa P, Cole SP. Helicobacter pylori preferentially induces interleukin 12 (IL-12) rather than IL-6 or IL-10 in human dendritic cells. Infect Immun 2003; 71:4163–4166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bergman MP, Engering A, Smits HH, et al. Helicobacter pylori modulates the T helper cell 1/T helper cell 2 balance through phase-variable interaction between lipopolysaccharide and DC-SIGN. J Exp Med 2004; 200:979–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hafsi N, Voland P, Schwendy S, et al. Human dendritic cells respond to Helicobacter pylori, promoting NK cell and Th1-effector responses in vitro. J Immunol 2004; 173:1249–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lundgren A, Strömberg E, Sjöling A, et al. Mucosal FOXP3-expressing CD4+ CD25 high regulatory T cells in Helicobacter pylori-infected patients. Infect Immun 2005; 73:523–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beswick EJ, Pinchuk IV, Das S, et al. Expression of the programmed death ligand 1, B7-H1, on gastric epithelial cells after Helicobacter pylori exposure promotes development of CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. Infect Immun 2007; 75:4334–4341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kao JY, Zhang M, Miller MJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori immune escape is mediated by dendritic cell-induced Treg skewing and Th17 suppression in mice. Gastroenterology 2010; 138:1046–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arnold IC, Lee JY, Amieva MR, et al. Tolerance rather than immunity protects from Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric preneoplasia. Gastroenterology 2011; 140:199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arnold IC, Dehzad N, Reuter S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents allergic asthma in mouse models through the induction of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest 2011; 121:3088–3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Codolo G, Mazzi P, Amedei A, et al. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori down-modulates Th2 inflammation in ovalbumin-induced allergic asthma. Cell Microbiol 2008; 10:2355–2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.D’Elios MM, Codolo G, Amedei A, et al. Helicobacter pylori, asthma and allergy. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2009; 56:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Engler DB, Reuter S, van Wijck Y, et al. Effective treatment of allergic airway inflammation with Helicobacter pylori immunomodulators requires BATF3-dependent dendritic cells and IL-10. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:11810–11815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song WJ, Chang YS, Lim MK, et al. Staphylococcal enterotoxin sensitization in a community-based population: a potential role in adult-onset asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2014; 44:553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park HW, Song WJ, Kim SH, et al. Classification and implementation of asthma phenotypes in elderly patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2015; 114:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song WJ, Kim MY, Jo EJ, et al. Rhinitis in a community elderly population: relationship with age, atopy, and asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2013; 111:347–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]