Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Abstract

Child–Pugh and MELD scores have been widely used for the assessment of prognosis in liver cirrhosis. A systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to compare the discriminative ability of Child–Pugh versus MELD score to assess the prognosis of cirrhotic patients.

PubMed and EMBASE databases were searched. The statistical results were summarized from every individual study. The summary areas under receiver operating characteristic curves, sensitivities, specificities, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and diagnostic odds ratios were also calculated.

Of the 1095 papers initially identified, 119 were eligible for the systematic review. Study population was heterogeneous among studies. They included 269 comparisons, of which 44 favored MELD score, 16 favored Child–Pugh score, 99 did not find any significant difference between them, and 110 did not report the statistical significance. Forty-two papers were further included in the meta-analysis. In patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure, Child–Pugh score had a higher sensitivity and a lower specificity than MELD score. In patients admitted to ICU, MELD score had a smaller negative likelihood ratio and a higher sensitivity than Child–Pugh score. In patients undergoing surgery, Child–Pugh score had a higher specificity than MELD score. In other subgroup analyses, Child–Pugh and MELD scores had statistically similar discriminative abilities or could not be compared due to the presence of significant diagnostic threshold effects.

Although Child–Pugh and MELD scores had similar prognostic values in most of cases, their benefits might be heterogeneous in some specific conditions. The indications for Child–Pugh and MELD scores should be further identified.

INTRODUCTION

Liver cirrhosis has a high morbidity and mortality, which is the 14th most common cause of death all over the world and the 4th in central Europe. It leads to 1.03 million deaths per year in the world,1 and 170,000 deaths per year in Europe.2 The prevalence of liver cirrhosis may be underestimated, because patients at the early phase of liver cirrhosis are often asymptomatic, and most of patients with liver cirrhosis are admitted due to its related complications. The 1-year mortality of liver cirrhosis varies greatly from 1% to 57% according to the complications.3 It is necessary to use the prognostic models to identify high-risk patients.

Child–Pugh score was firstly proposed by Child and Turcotte to predict the operative risk in patients undergoing portosystemic shunt surgery for variceal bleeding. The primary version of Child–Pugh score included ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), nutritional status, total bilirubin, and albumin. Pugh et al4 modified the Child–Pugh classification by adding prothrombin time or international normalized ratio (INR) and removing nutritional status. Child–Pugh score has been widely used to assess the severity of liver dysfunction in clinical work.

Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score was initially created to predict the survival of patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS).5 The primary version of MELD score included the etiology of liver cirrhosis, but this variable was unnecessary.6 The present version of MELD score incorporated only 3 objective variables, including total bilirubin, creatinine, and INR. Currently, it has been used to rank the priority of liver transplantation (LT) candidates.

Child–Pugh and MELD scores have been widely used to predict the outcomes of cirrhotic patients. However, they have some drawbacks. First, 2 variables (i.e., ascites and HE) included in Child–Pugh score are subjective and may be variable according to the physicians’ judgment and the use of diuretics and lactulose. Second, INR, which is one component of both Child-Pugh and MELD scores, does not sufficiently reflect coagulopathy and consequently liver function in liver cirrhosis.7 Third, there is an interlaboratory variation in INR value.8

Until now, a large number of studies compared their discriminative abilities. But the results remained controversial. Some studies favored the Child–Pugh score, but the others were on the opposite side. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to compare the discriminative ability of Child–Pugh versus MELD score for the assessment of prognosis in cirrhotic patients.

METHODS

This work is registered on PROSPERO database (registration number: CRD42015019700). Because this work is a systematic review of literatures, the ethical approval and patient consent are not necessary.

Study Search and Selection

We searched the PubMed and EMBASE databases. The search terms were as follows: (“Child score” or “Child–Pugh score” or “Child–Turcotte–Pugh score”) and (“MELD score” or “model for end stage liver disease score”) and (“liver cirrhosis”). The last search was performed on April 20, 2015.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: patients had been definitely diagnosed as liver cirrhosis; both Child–Pugh and MELD scores were calculated; areas under receiver operating characteristic curve of Child–Pugh versus MELD scores were compared; and sensitivity, specificity, and number of patients with endpoint events were reported. We excluded the following papers: duplicated papers; case reports; reviews; letters; commentaries; corrections; and papers unrelated to comparison of Child–Pugh and MELD scores. We did not restrict the publication years or study design.

Data Extraction

We extracted the following data: First author, study design, regions of study, the number of patients and the number of patients analyzed, age, sex, study population, etiology of cirrhosis, proportion of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), endpoints, cut-off value, true positive value, false positive value, false negative value, and true negative value.

Quality Assessment

Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) 2, a revised version of QUADAS, was used for the quality assessment.9 We obtained the detailed information of the QUADAS 2 tool from the website (www.quadas.org). There are 4 key aspects incorporated: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. In the former 3 aspects, the risk of bias and applicability should be evaluated. In the last one, only the risk of bias should be evaluated. The risk of bias is judged as “low,” “high,” or “unclear.” If all the answers are “yes,” it should be judged as “low” risk. If any answer is “unclear,” it should be judged as “unclear” risk. If all answers are “no,” it should be judged as “high” risk. Similarly, the applicability is classified as “low concern,” “high concern,” or “unclear concern.” If the relevant information was not given, it would be classified as “unclear concern.”

Meta-Analysis

The true positive, false positive, false negative, and true negative values were extracted and entered into the Meta-DiSc software version 1.4. If the diagnostic threshold effect was not statistically significant (P > 0.05 in the Spearman correlation test), the diagnostic accuracy would be further evaluated by a random-effects model. The summary areas under receiver operating characteristic curves (AUSROCs) with standard errors (SEs) and Q indexes with SEs, summary sensitivities and specificities with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), summary positive and negative likelihood ratios (PLRs and NLRs) with 95%CIs, and summary diagnostic odds ratios (DORs) with 95%CIs were reported. A statistically significant difference between the 2 scores was evaluated by analyzing the lower and upper limits of 95%CIs. If the diagnostic threshold effect was statistically significant (P < 0.05 in the Spearman correlation test), only AUSROCs with SEs and Q indexes with SEs were reported, but not sensitivities, specificities, PLRs, NLRs, or DORs. The heterogeneity among studies was evaluated by Chi-square test and inconsistency index. P < 0.1 and/or I2 > 50% was suggestive of considerable heterogeneity.

RESULTS

Paper Selection

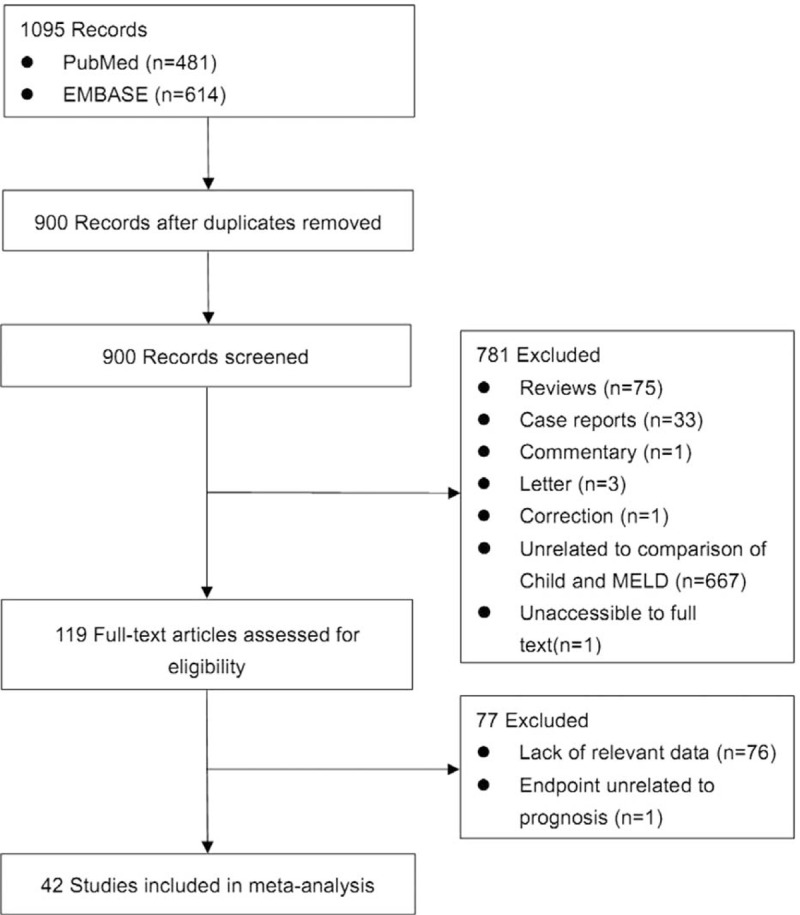

Overall, 1095 papers were identified via the 2 databases. According to the eligibility criteria, 119 papers were eligible for the systematic review (Figure 1).10–128

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of study inclusion.

Description of Study Characteristics

The characteristics of the 119 papers were shown in Table 1 . The countries included Austria (n = 1),11 Belgium (n = 2),38,96 China (n = 26),20,21,27,30,31,53–55,59,60,74,84,102,109,112,113,117,119–121,123–128 Cuba (n = 1),47 Czech Republic (n = 1),44 Egypt (n = 1),51 France (n = 6),25,37,41,71,77,114 Germany (n = 7),12,48–50,92,105,111 Greece (n = 1),82 Hungary (n = 1),61 India (n = 10),19,29,39,40,67,75,76,86,98,115 Iran (n = 1),87 Italy (n = 5),22,24,43,46,91 Ivory Coast (n = 1),13 Japan (n = 2),57,106 Mexico (n = 1),45 Nepal (n = 1),28 Pakistan (n = 2),62,97 Poland (n = 1),88 Portugal (n = 3),23,26,36 Serbia (n = 1),18 Singapore (n = 2),72,73 South Korea (n = 17),10,15,16,32,33,56,63–66,68–70,83,99,100,103 Spain (n = 7),14,58,89,90,94,95,116 Tunisia (n = 1),78 Turkey (n = 3),80,107,108 UK (n = 3),34,42,110 and USA (n = 11).17,35,52,79,81,85,93,101,104,118,122 The total number of patients analyzed in the included studies was 29,414. The number of patients varied from 17 to 2271.

TABLE 1.

Study Characteristics: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 1 (Continued).

Study Characteristics: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 1 (Continued).

Study Characteristics: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 1 (Continued).

Study Characteristics: An Overview of Studies

The characteristics of study population were heterogeneous among studies. According to the clinical presentations, etiology of liver diseases, patients’ conditions, and treatment options, they were mainly classified as follows: patients presenting with acute gastrointestinal bleeding (n = 12),14,15,26,45,57,69,81,84,89,94,109,117 patients presenting with ascites (n = 2),65,96 patients presenting with HE (n = 1),10 patients presenting with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) (n = 5),40,58,86,119,128 patients presenting with infection, sepsis, or spontaneous bacterial empyema (n = 5),30,62,72,73,116 patients admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) (n = 10),34,37,42,71,78,80,107,108,110,112 patients with trauma (n = 2),35,93 patients with viral hepatitis-related liver cirrhosis alone (n = 3),27,56,79 patients with alcohol-related liver cirrhosis alone (n = 5),19,61,70,75,120 patients undergoing TIPS (n = 8),11,31,44,91,92,101,113,123 patients undergoing LT (n = 10),23,38,41,48,67,87,88,105,115,122 patients undergoing abdominal, cardiac, or other surgery/procedure (n = 13),12,17,32,36,52,63,85,99,102,104,111,114,125 and unselected patients with liver cirrhosis (n = 43).13,16,18,20–22,24,25,28,29,33,39,43,46,47,49,51,53–55,59,60,64,66,68,74,76,77,82,83,90,95,97,98,100,103,106,118,121,124,126,127 In 42 studies, no patient with HCC was included;11,15,18,20–22,24–26,29,31,33,45–47,49,50,53–56,59,61,64,66,69,74,82,84,86,95,97,98,101–103,117,119,122–124,128 in 57 studies, the information regarding the number of patients with HCC was lacking;12,13,17,19,23,28,30,32,34,35,37,39,40,42–44,48,52,57,58,60,62,63,65,67,70,71,73,75–77,79–81,83,85,87,88,91–93,99,100,104,105,110–116,118,120,121,125,126 and in 20 studies, 1.9% to 52.8% of included patients were diagnosed with HCC.10,14,16,27,36,38,41,51,68,72,78,89,90,94,96,106–109,127

Description of Statistical Results

Their statistical results were summarized in Table 2 . There were 269 comparisons between MELD and Child–Pugh scores. Among 60 comparisons, a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) was observed. In details, the superiority of MELD score over Child–Pugh score was observed in 44 comparisons; and the superiority of Child–Pugh score over MELD score was observed in 16 comparisons. Among 99 comparisons, no statistically significant difference (P ≥ 0.05) was observed. Among 110 comparisons, the statistical significance was not reported.

TABLE 1 (Continued).

Study Characteristics: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 2.

Results of Comparison Between MELD and Child–Pugh Score: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 2 (Continued).

Results of Comparison Between MELD and Child–Pugh Score: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 2 (Continued).

Results of Comparison Between MELD and Child–Pugh Score: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 2 (Continued).

Results of Comparison Between MELD and Child–Pugh Score: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 2 (Continued).

Results of Comparison Between MELD and Child–Pugh Score: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 2 (Continued).

Results of Comparison Between MELD and Child–Pugh Score: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 2 (Continued).

Results of Comparison Between MELD and Child–Pugh Score: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 2 (Continued).

Results of Comparison Between MELD and Child–Pugh Score: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 2 (Continued).

Results of Comparison Between MELD and Child–Pugh Score: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 2 (Continued).

Results of Comparison Between MELD and Child–Pugh Score: An Overview of Studies

Study Quality

The brief explanation of study quality was presented in Table 3 . As for the risk of bias, 48 and 71 studies had low and unclear risks in the term of patient selection, respectively; 119 studies had low risks in the term of index tests; 117 and 2 studies had low and unclear risks in the term of reference standard, respectively; 91 and 28 studies had low and unclear risks in the term of flow and timing, respectively. As for the applicability concerns, 94 and 25 studies had low and high concerns in the term of patient selection, respectively; 2, 1, and 116 studies had low, unclear, and high concerns in the term of index test, respectively; 1 and 118 studies had low and high concerns in the term of reference standard, respectively.

TABLE 1 (Continued).

Study Characteristics: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 3.

Quality Assessment

TABLE 3 (Continued).

Quality Assessment

TABLE 3 (Continued).

Quality Assessment

Meta-Analysis

As for the meta-analysis, 77 papers were excluded,12,14–16,20–23,26–31,33–39,41,43–47,49–51,53–55,57–60,63,64,66,68–73,75,78,79,81–83,85,86,88–90,92,93,95,96,99–101,103,105,106,113,114,118,120–124,126,128 because 76 studies were lacking of relevant data12,14–16,20–23,26–31,33–39,41,43–47,49–51,53–55,57–59,63,64,66,68–73,75,78,79,81–83,85–86,88–90,92,93,95,96,99–101,103,105,106,113,114,118,120–124,126,128 and 1 study had the endpoint unrelated to the prognosis.60 Finally, 42 papers were included (Figure 1).10,11,13,17–19,24,25,32,40,42,48,52,56,61–63,67,74,76,77,80,84,87,91,94,97,98,102,104,107–112,115–117,119,125,127 Data extracted from these papers were summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Meta-analyses were performed according to the clinical presentations, etiology of liver diseases, patients’ conditions, treatment options, and endpoints (Table 4).

TABLE 1 (Continued).

Study Characteristics: An Overview of Studies

TABLE 4.

Results of Meta-Analyses

Subgroup Analysis According to the Clinical Presentations

Two studies were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh versus MELD score in patients with ACLF.40,119 The mean AUSROC of MELD score was larger than that of Child–Pugh score. There was no statistically significant diagnostic threshold effect in the meta-analysis of Child–Pugh or MELD score. The 95%CIs of DORs, NLRs, and PLRs were overlapped between them. But the 95%CIs of sensitivities and specificities were not overlapped. Child–Pugh score had a higher summary sensitivity than MELD score, but MELD score had a higher summary specificity than Child–Pugh score.

Four studies were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh versus MELD score in patients with UGIB.84,94,109,117 The mean AUSROC of MELD score was larger than that of Child–Pugh score. There was a statistically significant diagnostic threshold effect in the meta-analysis of MELD score. Thus, DOR, NLR, PLR, sensitivity, or specificity of MELD score was not calculated.

Subgroup Analysis According to the Etiology of Liver Diseases

Two studies were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh versus MELD score in patients with alcohol alone related liver cirrhosis.19,61 The mean AUSROC of Child–Pugh score was larger than that of MELD score. There was no statistically significant diagnostic threshold effect in the meta-analysis of Child–Pugh or MELD score. The 95%CIs of DORs, NLRs, PLRs, sensitivities, and specificities were overlapped between them.

Two studies were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh versus MELD score in patients with hepatitis B virus alone related liver cirrhosis.56,119 The mean AUSROC of MELD score was larger than that of Child–Pugh score. There was a statistically significant diagnostic threshold effect in the meta-analysis of MELD score. Thus, DOR, NLR, PLR, sensitivity, or specificity of MELD score was not calculated.

Subgroup Analysis According to the Patients’ Conditions

Six studies were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh versus MELD score in patients admitted to ICU.42,80,107,108,110,112 The mean AUSROC of MELD score was larger than that of Child–Pugh score. There was no statistically significant diagnostic threshold effect in the meta-analysis of Child–Pugh or MELD score. The 95%CIs of DORs, PLRs, and specificities were overlapped between them. But the 95%CIs of NLRs and sensitivities were not overlapped. MELD score had a smaller summary NLR and a higher summary sensitivity than Child–Pugh score.

Four studies were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh versus MELD score in LT candidates.48,67,87,115 The mean AUSROC of MELD score was larger than that of Child–Pugh score. There was no statistically significant diagnostic threshold effect in the meta-analysis of Child–Pugh or MELD score. The 95%CIs of DORs, NLRs, PLRs, sensitivities, and specificities were overlapped between them.

Subgroup Analysis According to the Treatment Options

Five studies were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh versus MELD score in patients who underwent surgery.17,32,52,104,111 The mean AUSROC of Child–Pugh score was larger than that of MELD score. There was no statistically significant diagnostic threshold effect in the meta-analysis of Child–Pugh or MELD score. The 95%CIs of DORs, NLRs, PLRs, and sensitivities were overlapped between them. But the 95%CIs of specificities were not overlapped. Child–Pugh score had a higher summary specificity than MELD score.

Two studies were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh versus MELD score in patients who underwent TIPS.11,91 Because only 2 comparisons were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis, the mean AUSROCs of Child–Pugh and MELD scores could not be calculated. The 95%CIs of DORs, NLRs, PLRs, sensitivities, and specificities were overlapped between them.

Subgroup Analysis According to the Endpoints

Five studies were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh versus MELD score for predicting the in-hospital mortality.62,84,110–112 The mean AUSROC of MELD score was larger than that of Child–Pugh score. There was a statistically significant diagnostic threshold effect in the meta-analysis of Child–Pugh score. DOR, NLR, PLR, sensitivity, or specificity of Child–Pugh score was not calculated.

Eight studies were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh versus MELD score for predicting the 3-month mortality.11,19,32,74,91,94,117,119 The mean AUSROC of MELD score was larger than that of Child–Pugh score. There were statistically significant diagnostic threshold effects in the meta-analyses of Child–Pugh and MELD scores. DORs, NLRs, PLRs, sensitivities, or specificities of Child–Pugh and MELD scores were not calculated.

Seven studies were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh versus MELD score for predicting the 6-month mortality.19,24,25,56,67,76,127 The mean AUSROC of MELD score was larger than that of Child–Pugh score. There was a statistically significant diagnostic threshold effect in the meta-analysis of Child–Pugh score. DOR, NLR, PLR, sensitivity, or specificity of Child–Pugh score was not calculated.

Eight studies were eligible for the subgroup meta-analysis to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh versus MELD score for predicting the 12-month mortality.13,24,61,65,77,94,117,127 The mean AUSROC of Child–Pugh score was larger than that of MELD score. There was no statistically significant diagnostic threshold effect in the meta-analysis of Child–Pugh or MELD score. The 95%CIs of DORs, NLRs, PLRs, sensitivities, and specificities were overlapped between them.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive review to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of Child–Pugh and MELD scores in patients with liver cirrhosis. Indeed, several previous narrative reviews regarding their prognostic values had been published by top experts.129–131 By comparison, our study employed a systematic search strategy to maximize the number of relevant papers. Several additional strengths included: the study and patient characteristics were systematically analyzed; the study quality was carefully evaluated; the clinical significance of Child–Pugh and MELD scores was further subdivided according to the different study population; and the meta-analysis was employed to synthesize the statistical results. Some remarkable findings should be summarized as follows.

First, in patients with ACLF, Child–Pugh score had a significantly higher sensitivity than MELD score, because the 95%CIs were not overlapped among them and the lower limit of 95%CI of Child–Pugh score was higher than the upper limit of 95%CI of MELD score (0.73 > 0.71); by contrast, MELD score had a significantly higher specificity than Child–Pugh score, because the 95%CIs were not overlapped among them and the lower limit of 95%CI of MELD score was higher than the upper limit of 95%CI of Child–Pugh score (0.70 > 0.58). These findings suggested that Child–Pugh score might have a better discriminative ability to predict the probability of developing some endpoint events in patients with ACLF, and that MELD score might have a better discriminative ability to predict the probability of free of developing some endpoint events in such patients.

Second, in patients admitted to ICU, MELD score had a significantly smaller NLR than Child–Pugh score, because the 95%CIs were not overlapped among them and the upper limit of 95%CI of MELD score was smaller than the lower limit of 95%CI of Child–Pugh score (0.35<0.36). MELD score also had a significantly higher sensitivity than Child–Pugh score, because the 95%CIs were not overlapped among them and the lower limit of 95%CI of MELD score was higher than the upper limit of 95%CI of Child–Pugh score (0.76 > 0.71). These findings suggested that MELD score might have a better discriminative ability to predict the probability of developing some endpoint events in such patients.

Third, in patients undergoing surgery, Child–Pugh score had a significantly higher specificity than MELD score, because the 95%CIs were not overlapped among them and the lower limit of 95%CI of Child–Pugh score was higher than the upper limit of 95%CI of MELD score (0.79 > 0.73). These findings suggested that Child–Pugh score might have a better discriminative ability to predict the probability of free of developing some endpoint events in such patients.

Fourth, Child–Pugh and MELD scores had statistically similar discriminative abilities in some subgroups (i.e., patients with alcohol alone related liver cirrhosis, LT candidates, patients undergoing TIPS, and 12-month mortality as the endpoint).

Fifth, because of statistically significant diagnostic threshold effects, DORs, NLRs, PLRs, sensitivities, or specificities could not be compared in some subgroups (i.e., patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding, patients with hepatitis B virus alone related liver cirrhosis, in-hospital mortality as the endpoint, 3-month mortality as the endpoint, and 6-month mortality as the endpoint).

Our study had 2 major limitations. First, although a great number of papers were included in the systematic review, not all included studies were eligible for our meta-analysis. Additionally, in some subgroup analyses, DORs, NLRs, PLRs, sensitivities, or specificities were not available. Thus, the combination of data from some selected papers could result in the potential bias. Second, the cut-off values of Child–Pugh and MELD scores for the assessment of prognosis were different among included studies. Therefore, we could not obtain any accurate thresholds for identifying the high-risk or low-risk patients.

In conclusion, we provided an overview regarding the comparison of Child–Pugh and MELD scores for the assessment of prognosis in liver cirrhosis. Both of them had similar prognostic significance in most of cases. However, given their distinctive benefits for some specific conditions, further studies might be necessary to clarify the candidates who should use Child–Pugh or MELD score for the assessment of prognosis and the timing when we should use Child–Pugh or MELD score for the assessment of prognosis. New scores should also be proposed to more accurately assess the prognosis of patients with liver disease based on prospective studies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ACLF = acute-on-chronic liver failure, AUSROC = summary areas under receiver operating characteristic curve, CI = confidence interval, DOR = diagnostic odds ratio, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, HE = hepatic encephalopathy, ICU = intensive care unit, INR = international normalized ratio, LT = liver transplantation, MELD = model for end-stage liver disease, NLR = negative likelihood ratio, PLR = positive likelihood ratio, QUADAS = Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies, SE = standard error, TIPS = transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts.

YP and XQ contributed equally to this work.

XQ: conceived the study, performed the literature search and selection, data extraction, quality assessment, and statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript; YP: performed the literature search and selection, data extraction, quality assessment, and statistical analysis; XG: gave critical comments and revised the manuscript. All authors have made an intellectual contribution to the manuscript and approved the submission.

This study was partially supported by the grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81500474) and Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (no. 2015020409).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380:2095–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blachier M, Leleu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M, et al. The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J Hepatol 2013; 58:593–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol 2006; 44:217–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, et al. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 1973; 60:646–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, et al. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 2000; 31:864–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamath PS, Kim WR, Advanced Liver Disease Study G. The model for end-stage liver disease (MELD). Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 2007; 45:797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bedreli S, Sowa JP, Gerken G, et al. Management of acute-on-chronic liver failure: rotational thromboelastometry may reduce substitution of coagulation factors in liver cirrhosis. Gut 2016; 65:357–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trotter JF, Olson J, Lefkowitz J, et al. Changes in international normalized ratio (INR) and model for endstage liver disease (MELD) based on selection of clinical laboratory. Am J Transplant 2007; 7:1624–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155:529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An J, Kim KW, Han S, et al. Improvement in survival associated with embolisation of spontaneous portosystemic shunt in patients with recurrent hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39:1418–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angermayr B, Cejna M, Karnel F, et al. Child-Pugh versus MELD score in predicting survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Gut 2003; 52:879–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arif R, Seppelt P, Schwill S, et al. Predictive risk factors for patients with cirrhosis undergoing heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2012; 94:1947–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attia KA, Ackoundou-N’guessan KC, N’Dri-Yoman AT, et al. Child-Pugh-Turcott versus Meld score for predicting survival in a retrospective cohort of black African cirrhotic patients. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14:286–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Augustin S, Muntaner L, Altamirano JT, et al. Predicting early mortality after acute variceal hemorrhage based on classification and regression tree analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7:1347–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bae WK, Lee JS, Kim NH, et al. [Usefulness of DeltaMELD/month for prediction of the mortality in the first episode of variceal bleeding patients with liver cirrhosis: comparison with CTP, MELD score and DeltaCTP/month]. Korean J Hepatol 2007; 13:51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bang CS, Suk KT, Kim DJ. Clinical significance of hepatic venous pressure gradient measurement in the risk assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int 2014; 8:S387. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Befeler AS, Palmer DE, Hoffman M, et al. The safety of intra-abdominal surgery in patients with cirrhosis: model for end-stage liver disease score is superior to Child-Turcotte-Pugh classification in predicting outcome. Arch Surg (Chicago, Ill: 1960) 2005; 140:650–654.discussion 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benedeto-Stojanov D, Nagorni A, Bjelakovic G, et al. The model for the end-stage liver disease and Child-Pugh score in predicting prognosis in patients with liver cirrhosis and esophageal variceal bleeding. Vojnosanitet Pregl 2009; 66:724–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhise SB, Dias RJ, Mali KK. Prognostic value of the monoethylglycinexylidide test in alcoholic cirrhosis. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2007; 13:118–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bie CQ, Yang DH, Tang SH, et al. Value of (Delta)MELD in evaluating the prognosis of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. World Chin J Digestol 2007; 15:3135–3139. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bie CQ, Yang DH, Tang SH, et al. The value of model for end-stage liver disease and Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores over time in evaluating the prognosis of patients with decompensated cirrhosis: experience in the Chinese mainland. Hepatol Res 2009; 39:779–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biselli M, Dall’Agata M, Gramenzi A, et al. A new prognostic model to predict dropout from the waiting list in cirrhotic candidates for liver transplantation with MELD score <18. Liver Int 2015; 35:184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boin Ide F, Leonardi MI, Udo EY, et al. [The application of MELD score in patients submitted to liver transplantation: a retrospective analysis of survival and the predictive factors in the short and long term]. Arq Gastroenterol 2008; 45:275–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Botta F, Giannini E, Romagnoli P, et al. MELD scoring system is useful for predicting prognosis in patients with liver cirrhosis and is correlated with residual liver function: a European study. Gut 2003; 52:134–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boursier J, Cesbron E, Tropet AL, et al. Comparison and improvement of MELD and Child-Pugh score accuracies for the prediction of 6-month mortality in cirrhotic patients. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009; 43:580–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cerqueira RM, Andrade L, Correia MR, et al. Risk factors for in-hospital mortality in cirrhotic patients with oesophageal variceal bleeding. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 24:551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan HL, Chim AM, Lau JT, et al. Evaluation of model for end-stage liver disease for prediction of mortality in decompensated chronic hepatitis B. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101:1516–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaurasia RK, Pradhan B, Chaudhary S, et al. Child-Turcotte-Pugh versus model for end stage liver disease score for predicting survival in hospitalized patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2013; 11:9–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chawla YK, Kashinath RC, Duseja A, et al. Predicting Mortality Across a Broad Spectrum of Liver Disease-An Assessment of Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP), and Creatinine-Modified CTP Scores. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2011; 1:161–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CH, Shih CM, Chou JW, et al. Outcome predictors of cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial empyema. Liver Int 2011; 31:417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen H, Bai M, Qi X, et al. Child-Na score: a predictive model for survival in cirrhotic patients with symptomatic portal hypertension treated with TIPS. PloS One 2013; 8:e79637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho HC, Jung HY, Sinn DH, et al. Mortality after surgery in patients with liver cirrhosis: comparison of Child-Turcotte-Pugh, MELD and MELDNa score. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 23:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi PC, Kim HJ, Choi WH, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease, model for end-stage liver disease-sodium and Child-Turcotte-Pugh scores over time for the prediction of complications of liver cirrhosis. Liver Int 2009; 29:221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cholongitas E, Betrosian A, Senzolo M, et al. Prognostic models in cirrhotics admitted to intensive care units better predict outcome when assessed at 48 h after admission. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 23 ((8 Pt 1)):1223–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corneille MG, Nicholson S, Richa J, et al. Liver dysfunction by model for end-stage liver disease score improves mortality prediction in injured patients with cirrhosis. J Trauma 2011; 71:6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costa BP, Sousa FC, Serodio M, et al. Value of MELD and MELD-based indices in surgical risk evaluation of cirrhotic patients: retrospective analysis of 190 cases. World J Surg 2009; 33:1711–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das V, Boelle PY, Galbois A, et al. Cirrhotic patients in the medical intensive care unit: early prognosis and long-term survival. Crit Care Med 2010; 38:2108–2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Degre D, Bourgeois N, Boon N, et al. Aminopyrine breath test compared to the MELD and Child-Pugh scores for predicting mortality among cirrhotic patients awaiting liver transplantation. Transpl Int 2004; 17:31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dhiman RK, Agrawal S, Gupta T, et al. Chronic Liver Failure-Sequential Organ Failure Assessment is better than the Asia-Pacific Association for the Study of Liver criteria for defining acute-on-chronic liver failure and predicting outcome. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:14934–14941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duseja A, Choudhary NS, Gupta S, et al. APACHE II score is superior to SOFA, CTP and MELD in predicting the short-term mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF). J Dig Dis 2013; 14:484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ecochard M, Boillot O, Guillaud O, et al. Could metabolic liver function tests predict mortality on waiting list for liver transplantation? A study on 560 patients. Clin Transpl 2011; 25:755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emerson P, McPeake J, O’Neill A, et al. The utility of scoring systems in critically ill cirrhotic patients admitted to a general intensive care unit. J Crit Care 2014; 29:1131.e1–1131.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fede G, Spadaro L, Tomaselli T, et al. Assessment of adrenocortical reserve in stable patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2011; 54:243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fejfar T, Safka V, Hulek P, et al. [MELD score in prediction of early mortality in patients suffering refractory ascites treated by TIPS]. Vnitr Lek 2006; 52:771–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flores-Rendon AR, Gonzalez-Gonzalez JA, Garcia-Compean D, et al. Model for end stage of liver disease (MELD) is better than the Child-Pugh score for predicting in-hospital mortality related to esophageal variceal bleeding. Ann Hepatol 2008; 7:230–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giannini E, Botta F, Fumagalli A, et al. Can inclusion of serum creatinine values improve the Child-Turcotte-Pugh score and challenge the prognostic yield of the model for end-stage liver disease score in the short-term prognostic assessment of cirrhotic patients? Liver Int 2004; 24:465–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gomez EV, Bertot LC, Gra Oramas B, et al. Application of a biochemical and clinical model to predict individual survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15:2768–2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gotthardt D, Weiss KH, Baumgartner M, et al. Limitations of the MELD score in predicting mortality or need for removal from waiting list in patients awaiting liver transplantation. BMC Gastroenterol 2009; 9:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gotzberger M, Singer J, Kaiser C, et al. Intrarenal resistance index as a prognostic parameter in patients with liver cirrhosis compared with other hepatic scoring systems. Digestion 2012; 86:349–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grunhage F, Rezori B, Neef M, et al. Elevated soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 75 concentrations identify patients with liver cirrhosis at risk of death. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6:1255–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hassan EA, Abd El-Rehim AS. A revised scope in different prognostic models in cirrhotic patients: Current and future perspectives, an Egyptian experience. Arab J Gastroenterol 2013; 14:158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoteit MA, Ghazale AH, Bain AJ, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease score versus Child score in predicting the outcome of surgical procedures in patients with cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14:1774–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huo TI, Lin HC, Wu JC, et al. Different model for end-stage liver disease score block distributions may have a variable ability for outcome prediction. Transplantation 2005; 80:1414–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huo TI, Lin HC, Wu JC, et al. Proposal of a modified Child-Turcotte-Pugh scoring system and comparison with the model for end-stage liver disease for outcome prediction in patients with cirrhosis. Liver Transpl 2006; 12:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huo TI, Wu JC, Lin HC, et al. Evaluation of the increase in model for end-stage liver disease (DeltaMELD) score over time as a prognostic predictor in patients with advanced cirrhosis: risk factor analysis and comparison with initial MELD and Child-Turcotte-Pugh score. J Hepatol 2005; 42:826–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hyun JJ, Seo YS, Yoon E, et al. Comparison of the efficacies of lamivudine versus entecavir in patients with hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis. Liver Int 2012; 32:656–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ishizu Y, Kuzuya T, Honda T, et al. A simple scoring system using MELD-Na and the stage of hepatocellular carcinoma for prediction of early mortality after acute variceal bleeding in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 2014; 60:1193A. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jalan R, Saliba F, Pavesi M, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic score to predict mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol 2014; 61:1038–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang CM, Xie W, Wang ZH. Prognostic evaluation for patients with decompensated hepatic cirrhosis. J Dalian Med Univ 2009; 31:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiang J, Ye JJ, Liu GY, et al. Visualization of the biliary ducts on contrast enhanced MR cholangiography with Gd-EOB-DTPA: Relation with liver function in patients with liver cirrhosis. Chin J Med Imaging Technol 2013; 29:765–769. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kalabay L, Graf L, Voros K, et al. Human serum fetuin A/alpha2HS-glycoprotein level is associated with long-term survival in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis, comparison with the Child-Pugh and MELD scores. BMC Gastroenterol 2007; 7:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khan R, Abid S, Jafri W, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score as a useful prognostic marker in cirrhotic patients with infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2009; 19:694–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim DH, Kim SH, Kim KS, et al. Predictors of mortality in cirrhotic patients undergoing extrahepatic surgery: comparison of Child-Turcotte-Pugh and model for end-stage liver disease-based indices. ANZ J Surg 2014; 84:832–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim SY, Yim HJ, Lee J, et al. [Comparison of CTP, MELD, and MELD-Na scores for predicting short term mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis]. Korean J Gastroenterol 2007; 50:92–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim TY, Kim MY, Sohn IH, et al. Sarcopenia as a useful predictor for long-term mortality in cirrhotic patients with ascites. J Korean Med Sci 2014; 29:1253–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koo JK, Kim JH, Choi YJ, et al. Predictive value of Refit Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, Refit Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Na, and pre-existing scoring system for 3-month mortality in Korean patients with cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 28:1209–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krishnan A. Assessment of an optimal prognostic system for predicting mortality in patients awaiting liver transplantation: CTP vs meld. HPB 2013; 15:15. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kwon HJ, Koo KH, Han BH, et al. The prognostic value of hyponatremia in a well-defined population of patients with ascites due to cirrhosis. Hepatol Int 2014; 8:S386. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee JY, Lee JH, Kim SJ, et al. [Comparison of predictive factors related to the mortality and rebleeding caused by variceal bleeding: Child-Pugh score, MELD score, and Rockall score]. J Hepatol 2002; 8:458–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee M, Lee JH, Oh S, et al. CLIF-SOFA scoring system accurately predicts short-term mortality in acutely decompensated patients with alcoholic cirrhosis: a retrospective analysis. Liver Int 2015; 35:46–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Levesque E, Hoti E, Azoulay D, et al. Prospective evaluation of the prognostic scores for cirrhotic patients admitted to an intensive care unit. J Hepatol 2012; 56:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lim LG, Tan XX, Woo SJ, et al. Risk factors for mortality in cirrhotic patients with sepsis. Hepatol Int 2011; 5:800–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lim SG, Lim LG, Xuan X, et al. Risk factors for mortality in cirrhotic patients with sepsis. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 2009; 50:454A. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lv XH, Liu HB, Wang Y, et al. Validation of model for end-stage liver disease score to serum sodium ratio index as a prognostic predictor in patients with cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 24:1547–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mallaiyappan M, Sawalakhe NR, Sasidharan M, et al. Retrospective and prospective validation of model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score in predicting mortality in patients of alcoholic liver disease. Trop Gastroenterol 2013; 34:252–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mishra P, Desai N, Alexander J, et al. Applicability of MELD as a short-term prognostic indicator in patients with chronic liver disease: an Indian experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 22:1232–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moreno JP, Grandclement E, Monnet E, et al. Plasma copeptin, a possible prognostic marker in cirrhosis. Liver Int 2013; 33:843–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mouelhi L, Ben Hammouda I, Salem M, et al. Hospital mortality in cirrhotic patients admitted in intensive care unit: prognosis factors and impact of gravity scores. J Afr d’Hepato-Gastroenterol 2010; 4:17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nunes D, Fleming C, Offner G, et al. Noninvasive markers of liver fibrosis are highly predictive of liver-related death in a cohort of HCV-infected individuals with and without HIV infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105:1346–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Olmez S, Gumurdulu Y, Tas A, et al. Prognostic markers in cirrhotic patients requiring intensive care: a comparative prospective study. Ann Hepatol 2012; 11:513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Orloff MJ, Vaida F, Isenberg JI, et al. Child-Turcotte score versus MELD for prognosis in a randomized controlled trial of emergency treatment of bleeding esophageal varices in cirrhosis. J Surg Res 2012; 178:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Papatheodoridis GV, Cholongitas E, Dimitriadou E, et al. MELD vs Child-Pugh and creatinine-modified Child-Pugh score for predicting survival in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11:3099–3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Park SH, Suk KT, Kim EJ, et al. Prognostic significance of the hemodynamic and clinical staging in the prediction of mortality in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 2014; 60:1182A–1183A. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Peng Y, Qi X, Dai J, et al. Child-Pugh versus MELD score for predicting the in-hospital mortality of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8:751–757. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Perkins L, Jeffries M, Patel T. Utility of preoperative scores for predicting morbidity after cholecystectomy in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2:1123–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Radha Krishna Y, Saraswat VA, Das K, et al. Clinical features and predictors of outcome in acute hepatitis A and hepatitis E virus hepatitis on cirrhosis. Liver Int 2009; 29:392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rahimi-Dehkordi N, Nourijelyani K, Nasiri-Tousi M, et al. Model for End stage Liver Disease (MELD) and Child-Turcotte- Pugh (CTP) scores: Ability to predict mortality and removal from liver transplantation waiting list due to poor medical conditions. Arch Iran Med 2014; 17:118–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, Wasilewicz MP, Wunsch E, et al. Assessment of a modified Child-Pugh-Turcotte score to predict early mortality after liver transplantation. Transpl Proc 2009; 41:3114–3116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reverter E, Tandon P, Augustin S, et al. A MELD-based model to determine risk of mortality among patients with acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology 2014; 146:412–431.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ripoll C, Groszmann R, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. Hepatic venous pressure gradient predicts clinical decompensation in patients with compensated cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2007; 133:481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Salerno F, Merli M, Cazzaniga M, et al. MELD score is better than Child-Pugh score in predicting 3-month survival of patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. J Hepatol 2002; 36:494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schepke M, Roth F, Fimmers R, et al. Comparison of MELD, Child-Pugh, and Emory model for the prediction of survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98:1167–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Seamon MJ, Franco MJ, Stawicki SP, et al. Do chronic liver disease scoring systems predict outcomes in trauma patients with liver disease? A comparison of MELD and CTP. J Trauma 2010; 69:568–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sempere L, Palazon JM, Sanchez-Paya J, et al. Assessing the short- and long-term prognosis of patients with cirrhosis and acute variceal bleeding. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2009; 101:236–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Serra MA, Puchades MJ, Rodriguez F, et al. Clinical value of increased serum creatinine concentration as predictor of short-term outcome in decompensated cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004; 39:1149–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Serste T, Gustot T, Rautou PE, et al. Severe hyponatremia is a better predictor of mortality than MELDNa in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. J Hepatol 2012; 57:274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shaikh S, Ghani H, Memon S, et al. MELD era: is this time to replace the original Child-Pugh score in patients with decompensated cirrhosis of liver. J Coll Physicians Surg 2010; 20:432–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sharma P, Sharma BC. Predictors of minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2010; 16:181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Song CS, Yoon MY, Kim HJ, et al. [Usefulness of model for end-stage liver disease score for predicting mortality after intra-abdominal surgery in patients with liver cirrhosis in a single hospital]. Korean J Gastroenterol 2011; 57:340–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Song DS, Kim DJ, Kim TY, et al. The usefulness of prognostic factors of acute-on chronic liver failure in patients with liver cirrhosis: a multicenter, retrospective cohort study in Korea (KACLiF Study). Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 2014; 60:552A–553A. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Stewart CA, Malinchoc M, Kim WR, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy as a predictor of survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Liver Transpl 2007; 13:1366–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Su CW, Chan CC, Hung HH, et al. Predictive value of aspartate aminotransferase to alanine aminotransferase ratio for hepatic fibrosis and clinical adverse outcomes in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009; 43:876–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Suk KT, Bang CS, Lee YS, et al. Diagnostic significance of hepatic venous pressure gradient in the prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2014; 60:S261. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Suman A, Barnes DS, Zein NN, et al. Predicting outcome after cardiac surgery in patients with cirrhosis: a comparison of Child-Pugh and MELD scores. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2:719–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tacke F, Fiedler K, Trautwein C. A simple clinical score predicts high risk for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages from varices in patients with chronic liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2007; 42:374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Takaya H, Uemura M, Fujimura Y, et al. ADAMTS13 activity may predict the cumulative survival of patients with liver cirrhosis in comparison with the Child-Turcotte-Pugh score and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score. Hepatol Res 2012; 42:459–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tas A, Akbal E, Beyazit Y, et al. Serum lactate level predict mortality in elderly patients with cirrhosis. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2012; 124:520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tas A, Koklu S, Beyazit Y, et al. Thyroid hormone levels predict mortality in intensive care patients with cirrhosis. Am J Med Sci 2012; 344:175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Teng W, Chen WT, Ho YP, et al. Predictors of mortality within 6 weeks after treatment of gastric variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients. Medicine (United States) 2014; 93:e321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Theocharidou E, Pieri G, Mohammad AO, et al. The Royal Free Hospital score: a calibrated prognostic model for patients with cirrhosis admitted to intensive care unit. Comparison with current models and CLIF-SOFA score. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109:554–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Thielmann M, Mechmet A, Neuhauser M, et al. Risk prediction and outcomes in patients with liver cirrhosis undergoing open-heart surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010; 38:592–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tu KH, Jenq CC, Tsai MH, et al. Outcome scoring systems for short-term prognosis in critically ill cirrhotic patients. Shock (Augusta, GA) 2011; 36:445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tzeng WS, Wu RH, Lin CY, et al. Prediction of mortality after emergent transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement: use of APACHE II, Child-Pugh and MELD scores in Asian patients with refractory variceal hemorrhage. Korean J Radiol 2009; 10:481–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vanhuyse F, Maureira P, Portocarrero E, et al. Cardiac surgery in cirrhotic patients: results and evaluation of risk factors. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012; 42:293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Velayutham V, Sathyanesan J, Krishnan A, et al. Variation of meld vs child pugh score for predicting survival in patients in waiting list for liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2012; 18:S220. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Viasus D, Garcia-Vidal C, Castellote J, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia in patients with liver cirrhosis: clinical features, outcomes, and usefulness of severity scores. Medicine 2011; 90:110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang J, Wang AJ, Li BM, et al. MELD-Na: effective in predicting rebleeding in cirrhosis after cessation of esophageal variceal hemorrhage by endoscopic therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014; 48:870–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wiesner R, Edwards E, Freeman R, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers. Gastroenterology 2003; 124:91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wu SJ, Yan HD, Zheng ZX, et al. Establishment and validation of ALPH-Q score to predict mortality risk in patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure: a prospective cohort study. Medicine 2015; 94:e403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Xie YD, Feng B, Gao Y, et al. Characteristics of alcoholic liver disease and predictive factors for mortality of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2013; 12:594–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Xiong WJ, Liu F, Zhao ZX, et al. Application of an end-stage liver disease model in prediction of prognosis in patients with liver cirrhosis. World Chin J Digestol 2004; 12:1159–1162. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zapata R, Innocenti F, Sanhueza E, et al. Predictive models in cirrhosis: correlation with the final results and costs of liver transplantation in Chile. Transpl Proc 2004; 36:1671–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zhang F, Zhuge Y, Zou X, et al. Different scoring systems in predicting survival in Chinese patients with liver cirrhosis undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 26:853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zhang J, Lu F, Ouyang C, et al. [Respective analysis of dead patients with cirrhosis by Child-Pugh score and model of end-stage liver disease score]. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2012; 37:1021–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhang J, Ye L, Zhang J, et al. MELD scores and Child-Pugh classifications predict the outcomes of ERCP in cirrhotic patients with choledocholithiasis: a retrospective cohort study. Medicine 2015; 94:e433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zhang JY, Zhang FK, Wang BE, et al. [The prognostic value of end-stage liver disease model in liver cirrhosis]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2005; 44:822–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhang QB, Chen YT, Lian GD, et al. A combination of models for end-stage liver disease and cirrhosis-related complications to predict the prognosis of liver cirrhosis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2012; 36:583–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zheng MH, Shi KQ, Fan YC, et al. A model to determine 3-month mortality risk in patients with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:351–356.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV, Vangeli M, et al. Systematic review: The model for end-stage liver disease – should it replace Child-Pugh's classification for assessing prognosis in cirrhosis? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005; 22:1079–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Durand F, Valla D. Assessment of the prognosis of cirrhosis: Child-Pugh versus MELD. J Hepatol 2005; 42 (SUPPL. 1):S100–S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Durand F, Valla D. Assessment of prognosis of cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis 2008; 28:110–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.