Abstract

Scrub typhus is caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi. Any delay in diagnosis can result in delayed treatment and severe complications, including secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, which is rare but potentially fatal.

In this paper, the authors present 3 cases of secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with scrub typhus, successfully treated with chloramphenicol without additional antineoplastic therapy. All patients cured and achieved complete resolution.

This report highlights the effectiveness of chloramphenicol without the need for chemotherapy in the treatment of scrub typhus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a pediatric population under the age of 8 years.

INTRODUCTION

Scrub typhus is caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi. Scrub typhus is endemic in many Asian countries, including China, India, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and others regions in East and South East Asia.1 A delay in the diagnosis and treatment can result in severe complications, including disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).2

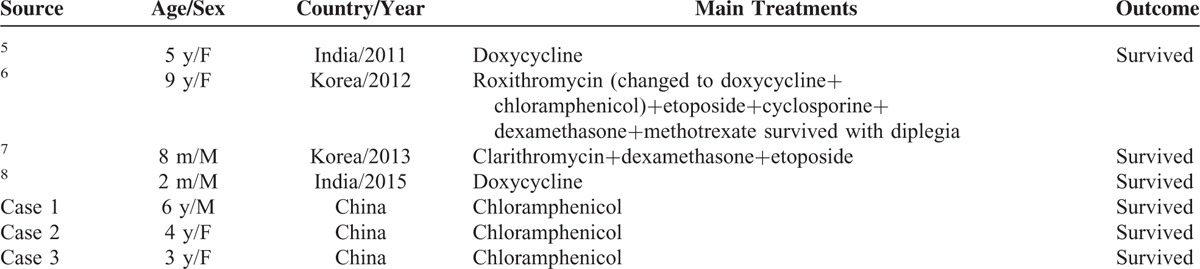

HLH is a rare but potentially fatal disease, characterized by a malfunction of natural killer T-cell function, activation and proliferation of lymphocytes or histiocytes with uncontrolled hemophagocytosis and cytokine overproduction.3 HLH phenotypically presents as 2 different conditions: primary (PHLH) and secondary (SHLH). SHLH has been associated with a variety of stimuli, such as infections, malignant neoplasia, and conditions characterized by immunosuprresion.4 The SHLH associated with scrub typhus has been reported only in 4 cases (Table 1).5–8 Here, we report 3 additional cases from the Southern part of China.

TABLE 1.

Reported Cases of Scrub Typhus-Associated Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in Children

CASE PRESENTATION

Case 1

A 6-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital in the context of fever of unknown origin for 7 days (August, 2009). Before admission, the boy was treated for 5 days with ceftriaxone for the presumptive diagnosis of sepsis. This boy lived in Cang-nan County, which is a rural area in South of China where scrub typhus is considered endemic. On examination, a temperature of 39.7°C was measured and a 1 × 0.5 cm necrotic cutaneous lesion was observed on the left shoulder (Figure 1A). Ultrasound examination revealed splenomegaly extending 4.0 cm below the left costal margin at the lowest point.

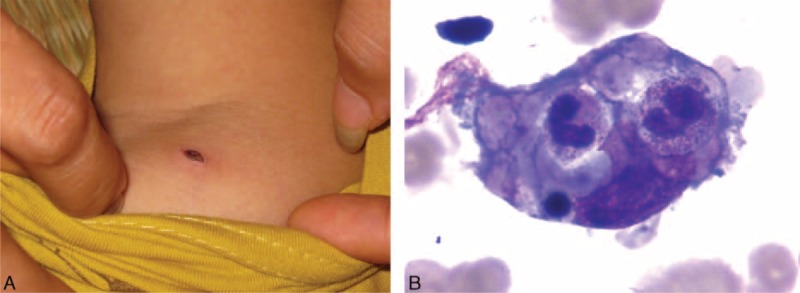

FIGURE 1.

(A) A necrotic cutaneous lesion at the left shoulder area in case 1. (B) Hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow in case 1.

The results of the blood analysis suggested the diagnosis of HLH. The detailed data is illustrated in Table 2. A bone marrow examination revealed hemophagocytosis (Figure 1B) without any evidence of malignancy. A Weil–Felix agglutination test for the diagnosis of rickettsial infections revealed a high anti-OXK titer of 1:160. Cultures from blood and urine culture were negative.

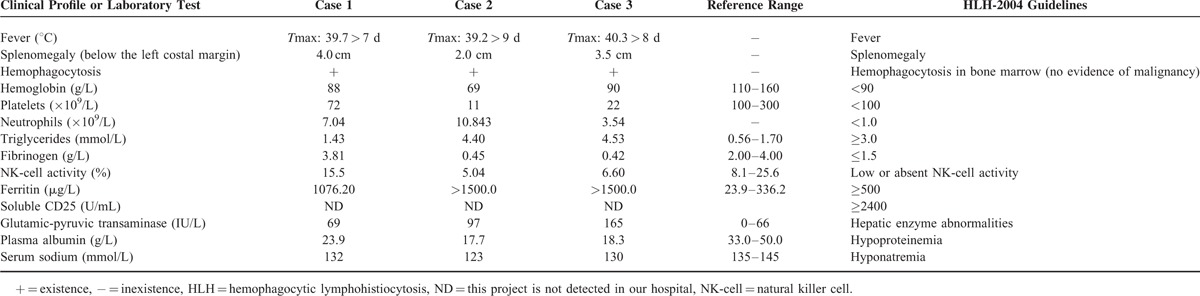

TABLE 2.

The Patients’ Clinical Profile and Main Laboratory Values

A final diagnosis of SHLH associated with scrub typhus was proposed and the patient was treated with chloramphenicol (45 mg kg–1 d–1, divided every 8 h). His fever subsided immediately within 24 h. After 11 days of chloramphenicol treatment, the boy was discharged from hospital with a completely remission.

Case 2

A 4-year-old girl presented with a history of fever and cough for 9 days (August, 2014). Before admission, she was treated for 3 days with azithromycin and 4 days with cefotaxime for the presumptive diagnosis of sepsis and pneumonia. This girl also lived in Cang-nan County, which is a rural area in South of China in which scrub typhus is endemic. On examination, the body temperature was 39.2°C. Additionally, a 0.5 × 0.5 cm necrotic cutaneous lesion was found in the right opisthotic area. Furthermore, she had an anemic appearance and disseminated ecchymosis was noticed on the facial region. Ultrasound examination revealed splenomegaly, extending 2.0 cm below the left costal margin at the lowest point.

The results of the blood tests suggested the diagnosis of HLH. The detailed data is summarized in Table 2. Findings from the chest x-ray suggested bronchitis. A bone marrow examination revealed hemophagocytosis without any of malignancy. A Weil–Felix agglutination test (for the diagnosis of rickettsial infections) revealed a high anti-OXK titer of 1:320. Blood culture and the bacterial culture of sputum were negative.

A diagnosis of SHLH associated with scrub typhus was proposed and the patient was treated with chloramphenicol (45 mg kg–1 d–1, divided every 8 h). The girl was afebrile 24 h after initiating the drug and cured after 9 days of chloramphenicol treatment.

Case 3

A 3-year-old girl presented with an 8-days history of fever with 2-days of vomiting (July, 2013). Before the admission, a treatment for 2 days with meropenem was initiated for the presumptive diagnosis of meningitis and sepsis. This girl also lived in Cangnan County. On examination, a temperature of 40.3°C was measured and a 0.5 × 0.5 cm necrotic cutaneous lesion at he left forearm was observed. Ultrasound examination revealed splenomegaly extending 3.5 cm below the left costal margin at the lowest point.

The results of the blood analysis suggested the diagnosis of HLH. More detailed data is summarized in Table 2. The bone marrow examination revealed hemophagocytosis without any evidence of malignancy. The Weil–Felix agglutination test for the diagnosis of rickettsial infections revealed a high anti-OXK titer of 1:320. The routine test and biochemistry of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were normal. Blood culture and CSF culture were negative.

A diagnosis of SHLH associated with scrub typhus was made after which the patient was treated with chloramphenicol (45 mg kg–1 d–1, divided every 8 h). Her fever subsided immediately. After 13 days of chloramphenicol treatment, peripheral blood counts normalized completely leading to full recovery.

All 3 patients were followed up for 1 year. Blood counts were obtained monthly, all of which remained normal. Two of 3 subject developed fever in the setting of upper respiratory tract infection during the follow-up period. Evaluation found no cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, or hypofibrinogenemia. Levels of ferritin and alanine transaminase also were normal.

DISCUSSION

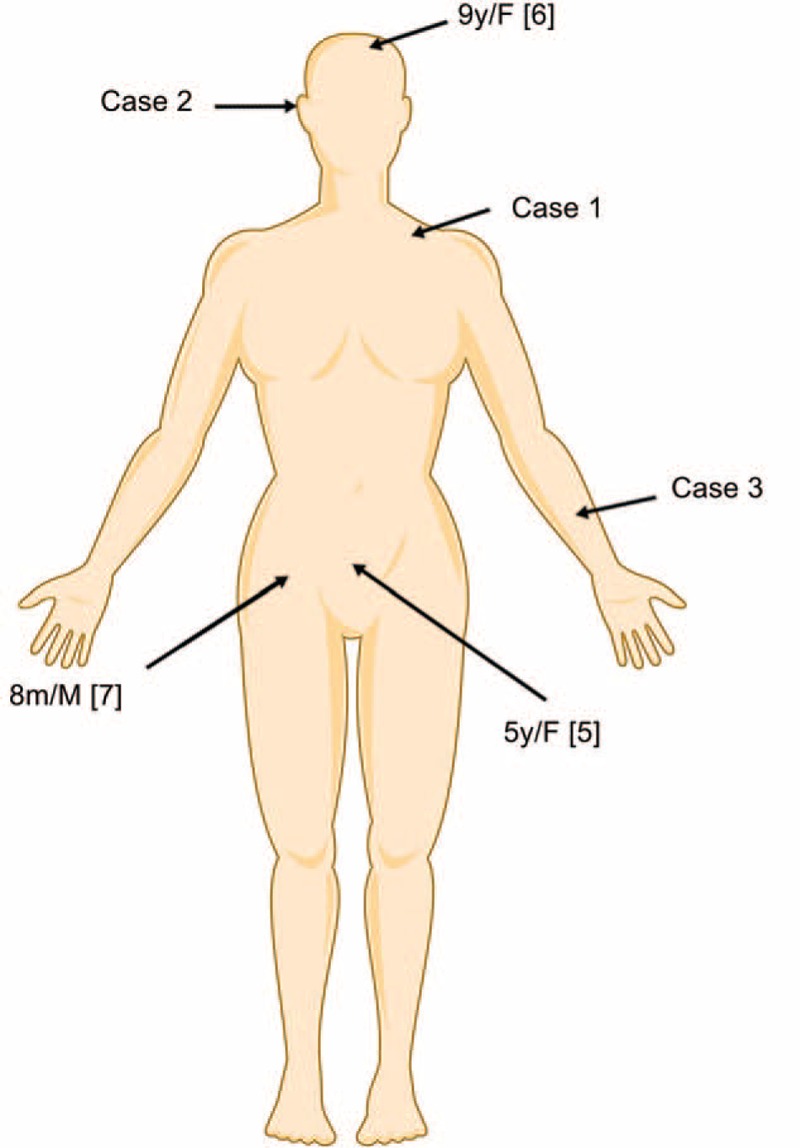

Scrub typhus is a common cause of acute febrile illness. As pathognomonic feature, the finding of a cutaneous lesion is essential for the diagnosis of this disease. However, it is sometimes difficult to be noticed at early stages because the lesion could appear at any (hidden) location (Figure 2). This is also the most important reason for a delayed diagnosis.

FIGURE 2.

The location of cutaneous lesions in different cases.

All our patients presented with fever and a pathognomonic lesion. A high anti-Proteus OX-K titer as observed by the Weil–Felix slide agglutination test was noticed.

All 3 cases presented with 5 out of 8 diagnostic HLH-2004 criteria (Table 2).9 In our patients, a clear association was found between scrub typhus and HLH as demonstrated by the diagnosis of scrub typhus and the complete resolution of the hemophagocytic condition after successful treatment with chloramphenicol.

Only a minimal amount of evidence based on epidemiologic data can be found related to SHLH cases with 20% of the cases initiated in relation to an infection.10 Scrub typhus-associated HLH is even more rare, Cascio et al reviewed 153 papers on SHLH in zoonoses between 1950 and 2012, and only 4 papers were associated with tsutsugamushi.11

The mortality rate of HLH as presented in the literature, ranged from 22% to 60%.12 Early diagnosis and treatment could improve the outcomes of HLH in children.13 The HLH-2004 guidelines are suitable for all patients with HLH, with or without evidence of genetic or familial disease, regardless of documented or suspected viral infections.9 Dexamethasone, etoposide, and cyclosporin A are recommended as the initial therapy in this protocol. Kleynberg and Schiller et al emphasized the importance of etoposide for the treatment of EBV infection associated with HLH.14 According to the reported papers,5–8 2 cases (age 5 years, 2 months, respectively) were treated with doxycycline5,8 and 1 case (age 9 years) was treated with doxycycline plus chloramphenicol with chemotherapy including etoposide, cyclosporine, dexamethasone, and methotrexate.6 All these patients survived. It seems effective to treat the scrub typhus-associated HLH in children by doxycycline with or without chemotherapy. However, 1 member of the tetracycline family, doxycycline, is banned for use in children under the age of 8 years in China (negative impact on bone growth and discoloration of permanent teeth). In addition, another case (age 8 months) treated by clarithromycin in association with etoposide resulted incomplete remission.7 However, in case 2, 3-day azithromycin was administered before hospital admission and another case was treated with empiric roxithromycin for 7 days before doxycycline plus chloramphenicol was given.6 The 2 patients continued to have daily fevers. The effective use of macrolides for scrub typhus-associated HLH in children is questionable.

Our 3 cases were treated with chloramphenicol without chemotherapy, resulting in complete resolution of the disease. Another 2 cases were found to be treated with doxycycline without chemotherapy also resulting in complete resolution.5,8 Considering the severe toxic and side effect to children, the use of chemotherapy (e.g., etoposide) in the treatment of scrub typhus-associated HLH in children may be unnecessary. The main side effects of chloramphenicol treatment are aplastic anaemia and bone marrow suppression. The former is very rare15 and the latter is fully reversible once the drug is stopped. All our patients had blood counts checked twice weekly during treatment and once monthly after discharge until 1 year. No aplastic anaemia or bone marrow suppression was noticed. In the children under the age of 8 years, chloramphenicol may be the most desirable drug in the treatment of scrub typhus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome.

Six of the 7 known cases with confirmed diagnosis in <10 days achieved complete resolution. Only 1 case resulted in permanent neurological sequelae but this patient had its diagnosis confirmed only on the 19th day after onset.6 Early diagnosis and treatment (e.g. within 10 days of onset) seem to be essential for preventing sequelae to appear based on this data.

CONCLUSION

In summary, these case reports present the therapy for scrub typhus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in children. With early diagnosis and treatment within a 10 days period after onset, sequelae seem not to appear. Chloramphenicol without the addition of chemotherapy as the treatment of scrub typhus-associated HLH in children under the age of 8 years may be an appropriate choice. However, large, prospective randomized controlled trials are needed.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome, DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulation, HLH = hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, PHLH = primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, SHLH = secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

Authors’ contributions: Y-HZ initiated the writing of the article and contributed in the discussion and review of the paper. F-QX focused on data collection and participated in writing the paper. SVP conceived the study and writing the article. M-HZ conceived the study, participated in the study design and supervision, and partnered in writing the paper.

Funding: there was no financial support or funding for this case report. Informed patient consent was obtained for publication of this case report.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zheng MH, Shi KQ, Chen YP. Skin lesion in a critically ill man. BMJ 2015; 351:h4570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cascio A, Correnti P, Iaria C. Scrub typhus, acute respiratory distress, and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Int J Infect Dis 2013; 17:e662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Usmani GN, Woda BA, Newburger PE. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of HLH. Br J Haematol 2013; 161:609–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang L, Zhou J, Sokol L. Hereditary and acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Cancer Control 2014; 21:301–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jayakrishnan MP, Veny J, Feroze M. Rickettsial infection with hemophagocytosis. Trop Doct 2011; 41:111–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han DK, Baek HJ, Shin MG, et al. Scrub typhus-associated severe hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with encephalomyelitis leading to permanent sequelae: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012; 34:531–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwon HJ, Yoo IH, Lee JW, et al. Life-threatening scrub typhus with hemophagocytosis and acute respiratory distress syndrome in an infant. J Trop Pediatr 2013; 59:67–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pazhaniyandi S, Lenin R, Sivathanu S. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with a leukemoid reaction in an infant with scrub typhus. J Infect Public Health 2015; 8:626–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Guidelines for Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007; 48:124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhote R, Simon J, Papo T, et al. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in adult systemic disease: report of twenty-six cases and literature review. Arthritis Rheum 2003; 49:633–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cascio A, Pernice LM, Barberi G, et al. Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in zoonoses. A systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2012; 16:1324–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin YH, Lin YH, Shi ZY. A case report of scrub typhus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome and a review of literature. Jpn J Infect Dis 2014; 67:115–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horne A1, Trottestam H, Aricò M, et al. Frequency and spectrum of central nervous system involvement in 193 children with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol 2008; 140:327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleynberg RL, Schiller GJ. Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: an update on diagnosis and therapy. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2012; 10:726–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallerstein RO, Condit PK, Kasper CK, et al. Statewide study of chloramphenicol therapy and fatal aplastic anemia. JAMA 1969; 208:2045–2050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]