Abstract

We report a case of a symptomatic relapse of HIV-related cryptococcal meningoencephalitis 8 years after the first diagnosis on the background of immune reconstitution. The findings as well as the clinical course suggests a combination of smouldering localized infection and enhanced inflammatory reaction related to immune restoration due to antiretroviral therapy. A combination of antifungal and anti-inflammatory therapy resulted in clinical and radiological improvement. Our case challenges the concept that immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and microbiological relapse are dichotomous entities.

Case Report

A 40-year old man with untreated HIV infection was diagnosed with cryptococcal meningitis in 2006. Serum CRAG titer was 1:1024. The patient was treated for 5 weeks with liposomal amphotericin B, 5-flucytosine and fluconazole. He recovered completely. Due to poor adherence he did not take fluconazole secondary prophylaxis and antiretroviral therapy (ART) regularly for the next 3 years. His CD4 count had fallen to 17 cells/μl (Figure 1a). Beginning in December 2009, the patient became adherent to his antiretroviral therapy consisting of tenofovir, emtricitabine, and efavirenz. By May 2010, his CD4 had risen to 123 cells/μl (CD4% of 5%) with a viral load of <100 copies/ml. His CD4 count increased up to 272 cells/μl by August 2013 with continuous HIV suppression (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

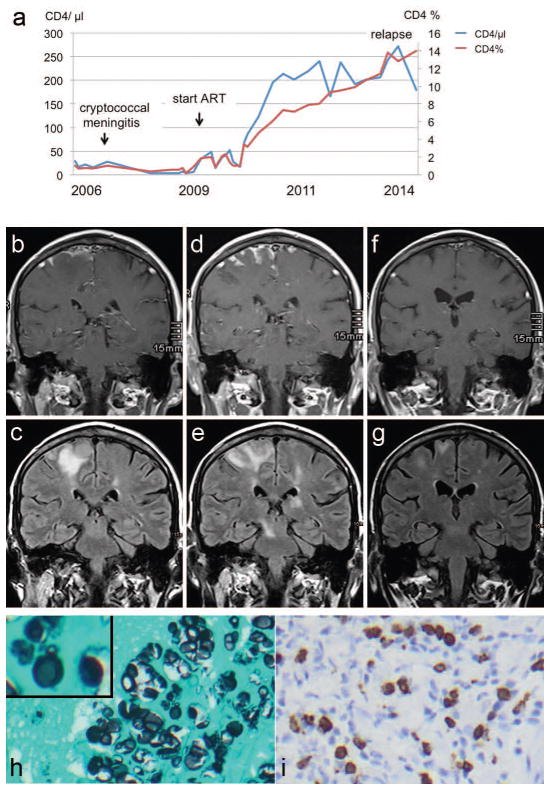

a. Time line of absolute CD4 cells/μl (blue line) and CD4 percentage of total lymphocyte population (red line) from 2006 through 2014.

b–g. Cerebral MRI imaging. b, d, f: Contrast enhanced T1 images. c, e, g: TIRM images. b,c. Imaging on admission showing prominent contrast meningeal enhancement (b) with underlying parenchymal edema (c). d,e. Follow-up imaging 4 weeks later, showing increased contrast enhancement (d) and cortical and subcortical edema and a new diecephalic- midbrain lesion (e) demonstrating the “lag phenomenon” in the radiologic appearances compared with clinical examination in CNS cryptococcosis. Two weeks later on completion of short steroid course there is a decrease of cortical contrast enhancement (f) and parenchymal edema (g).

h–i. Brain biopsy. h. Histological examination showing numerous yeast-like structures in the cortical tissue (Grocott stain, original magnification × 400). Inset. High power magnification showing yeast budding suggesting that some yeasts are viable. i. Immunohistochemical examination showing strong CD8+ cellular reaction in the parenchyma and subarachnoid space (mouse monoclonal antibody, Dako, Clon C8/144B, original magnification × 400).

In January 2014, within 3 days the patient experienced two focal sensory epileptic seizures affecting the left part of his body. On admission, left-sided distal leg paresis was detected. Cerebral MRI revealed multiple enhancing leptomeningeal and cortical lesions (Figure 1b,c). The CSF analysis showed 24 cells/μl, 90% lymphocytes, protein of 1 025 mg/l (normal range: 150–450) with normal lactate and normal glucose. The CSF opening pressure was 190 mmH2O. CSF India ink staining and CSF CRAG were negative on three consecutive LPs. Serum CRAG was 1:4. The full microbiological work-up on CSF including fungal cultures was negative.

A follow-up MRI one week later showed progression of the inflammatory lesions. Brain biopsy was performed revealing numerous yeast-like organisms in the subarachnoid space and brain parenchyma surrounded by a fierce inflammatory reaction (Figure 1h,i). Budding was detected in a very small fraction of the yeast cells (Figure 1h). Brain tissue did not grow fungus, even after prolonged culture for 28 days. PCR on DNA extracted brain tissue revealed fungal DNA identified as Cryptococcus spp., based on the ITS2 region of rDNA. The patient was started on liposomal amphotericin B (4 mg/kg/day) and 5-flucytosine (100 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks followed by fluconazole 400 mg/day. After two weeks of antifungal treatment, there was a slight improvement in strength of the left lower limb, yet, a repeat MRI revealed further progression of the lesions (Figure 1d,e). Prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) was added for 10 days with tapering over 7 days. Two weeks later the neurological examination revealed further improvement of muscle strength and MRI showed reduced edema and reduced contrast enhancement of the lesions (Figure 1f,g). On 3-month follow-up, neurological examination revealed normal muscle strength with mild spasticity. Brain MRI showed complete resolution of contrast enhancement and further reduction of lesion size.

Discussion

We describe a case of a patient with a symptomatic relapse eight years after the initial diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis. The findings and clinical course had features of both paradoxical IRIS and microbiological relapse [1–3] with the brain biopsy demonstrating numerous cryptococcal organisms surrounded by intense CD3+CD8+ T cell inflammation (Table 1). Both the brain tissue and CSF did not grow fungus. Lack of growth cannot fully exclude active microbial replication if the fungal CSF burden is low. In our case the lack of growth might also be due to technical issues because for the first 48 hours the tissue was cultured on bacterial media. Alternatively, the immune response may have simultaneously resulted in containment of a slow growing cryptococcal infection resulting in few viable organisms and negative culture. And yet, the finding of budding yeast cells proves that viable organisms were present in the brain and the meninges. Of note, CSF CRAG was negative despite the high fungal burden on biopsy, again a sign of confinement of the infection to the brain with little antigen shedding into the CSF.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory features of recurrence versus immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) in this case.

| Features suggestive of paradoxical IRIS |

|

| Features suggestive of microbiologic relapse |

|

A sterile CSF culture (or appropriately decreased quantitative culture) is diagnostic for cryptococcal IRIS [2], however our case demonstrates that the diagnosis of IRIS must not rely solely on these criteria.

The timing of the symptomatic relapse sheds light on the interplay between infection and inflammation in this disease. Interestingly, the patient did not show any signs or symptoms of a clinical relapse in the first 3 years following his initial diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis when his immune system was profoundly suppressed (CD4 <50 cells/ul). The clinical event occurred 40 months after his CD4 counts had increased to over 200 cells/μl (CD4% 9–16%). This course suggests that an adequate recovery of immune function was required to mount a response to cryptococcal antigen and produce a clinically evident symptomatic relapse. It also suggests that in the absence of an immune reaction, Cryptococcus are capable of maintaining a low grade “smouldering” CNS infection for as long as 8 years without producing any clinical symptoms.

In summary, our case illustrates that some cases of symptomatic deterioration of CNS cryptococcosis cannot always be distinctly classified as either microbiologic relapse or IRIS, and may be contributed to by both mechanisms. Combination antifungal and anti-inflammatory treatment might be prudent in such cases of intra-parenchymal involvement.

References

- 1.Musubire AK, Boulware DR, Meya DB, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Cryptococcal Relapse. J AIDS Clin Res. 2013 doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.s3-003. pii: S3–003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haddow LJ, Colebunders R, Meintjes G, et al. International Network for the Study of HIV-associated IRIS (INSHI). Cryptococcal immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV-1-infected individuals: proposed clinical case definitions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:791–802. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70170-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulware DR, Meya DB, Bergemann TL, et al. Clinical features and serum biomarkers in HIV immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome after cryptococcal meningitis: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]