Abstract

Psychotherapy research reveals consistent associations between therapeutic alliance and treatment outcomes in the youth literature; however, past research frequently suffered measurement issues that obscured temporal relationships between alliance and symptomatology by measuring variables later in therapy, thereby precluding examination of important early changes. The current study aimed to explore the directions of effect between alliance and outcome early in therapy with adolescents by examining associations between first- and fourth-session therapeutic alliance and symptomatology. Thirty-four adolescents (~63% female, 38% ethnic/racial minority) participated in a school-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents with depression. Participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory at baseline and Session 4, and therapeutic alliance was coded from audiotapes of Sessions 1 and 4 by objective coders using the Alliance Observation Coding System. Autoregressive path analyses determined that first-session therapeutic alliance was a strong significant predictor of Session 4 depression symptoms, but pretreatment depression scores were not significantly predictive of subsequent therapeutic alliance. Adding reciprocal effects between alliance and depression scores did not adversely affect model fit, suggesting that reciprocal effects may exist. Early therapeutic alliance with adolescents is critical to fostering early gains in depressive symptomatology. Knowing alliance’s subsequent effect on youth outcomes, clinicians should increase effort to foster a strong relationship in early sessions and additional research should be conducted on the reciprocal effects of therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in adolescence.

Mental health clinicians consistently report that the therapeutic relationship with youth clients is one of the most important predictors of treatment outcome (Campbell & Simmonds, 2011), of equal or greater importance than the specific techniques used or the frequency or duration of treatment. Likewise, research examining associations between child and adolescent therapeutic relationship factors and treatment outcome has corroborated clinician intuition (Bickman et al., 2012; Clark, 2013; Shirk, Karver, & Brown, 2011), revealing modest but consistent correlations between alliance and outcome similar to those found in the adult literature (Martin, Garske, & Davis, 2000; Orlinsky, Ronnestad, & Willutzki, 2004). As a result of these findings, advocates have encouraged greater exploration of the role of therapeutic alliance in the efficacy of youth mental health treatment (Green, 2006; Kendall & Ollendick, 2004).

Although comparatively little research has been conducted on youth alliance relative to the adult psychotherapy literature, many have theorized a direct causal relationship between therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome for youth, implying that therapeutic alliance may be an active component of therapy. For example, a youth’s experience of a warm, validating, and empathic relationship with an interested clinician may itself be a mechanism of change, or a youth’s interaction with a clinician may challenge the youth’s negative interpersonal schema, thus promoting change (Shirk & Russell, 1996). Others propose that the impact of alliance on symptomatology is mediated by specific tasks in psychotherapy. From this perspective, a positive therapeutic alliance may encourage and motivate the client to engage and participate in the work of psychotherapy, which leads to more positive outcomes (Kendall et al., 2009; Shirk & Karver, 2006). Alternatively, others submit that alliance is merely a marker of change, as opposed to a mechanism or precursor of change (Crits-Christoph, Gibbons, & Hearon, 2006), suggesting that a client may develop a more positive alliance with a therapist as a result of symptom improvement. Although competing theories abound, little empirical evidence exists to inform these theoretical discussions.

Crits-Christoph et al. (2006) asserted that the case for a causal relationship between therapeutic alliance and outcome would be strengthened if the direction of effect between alliance and outcome were more rigorously examined. Shirk and Karver (2003) and Shirk et al. (2011) also noted this problem, lamenting that many early studies of therapeutic alliance measured alliance and outcome simultaneously at the end of treatment, thus prohibiting any attempt to examine direction of effect. The vast majority of alliance research conducted with youth has not systematically measured alliance and symptomatology in the early stages of treatment or across the duration of treatment (Florsheim, Shotorbani, Guest-Warnick, Barratt, & Hwang, 2000; Simpson, Frick, Kahn, & Evans, 2013). With alliance and symptoms only measured at later time points, the directionality of effects is temporally confounded, potentially obscuring changes occurring early in therapy that are highly clinically relevant (Feeley, DeRubeis, & Gelfand, 1999). This dearth of research is particularly surprising, given the association between common factors and early treatment improvement in adults (Lambert, 2005) and the finding that early improvement in treatment is frequently associated with better long-term outcomes (Cromley & Lavigne, 2008; Delgadillo et al., 2013; Rynn, Khalid-Khan, Garcia-Espana, Etemad, & Rickels, 2006).

More recent studies of youth therapeutic alliance have attempted to determine the directionality of these effects by employing prospective methods in which alliance was measured early in psychotherapy and across multiple time points (Chiu, McLeod, Har, & Wood, 2009; Hogue, Dauber, Stambaugh, Cecero, & Liddle, 2006; Kazdin, Whitley, & Marciano, 2006; Shirk, Gudmundsen, Kaplinski, & McMakin, 2008). The majority of these studies indicate that the therapeutic alliance is a moderate predictor of youth symptomatology at subsequent sessions. However, although a prospective association between alliance and outcome is necessary for establishing alliance as a change mechanism in psychotherapy, it is far from sufficient (Shirk, Caporino, & Karver, 2010). Despite their improved methodology, these prospective studies still do not eradicate potential temporal confounds, as alliance was typically measured after several sessions of treatment. Substantial change in psychotherapy often occurs within the first few sessions of treatment, and early changes are known to be reliable predictors of treatment outcome (Cromley & Lavigne, 2008; Delgadillo et al., 2013). These findings, coupled with the fact that sudden gains in psychotherapy are often followed by increases in therapeutic alliance (Tang & DeRubeis, 1999), illustrate how measurement of alliance after several sessions is a serious methodological flaw. For example, a child may experience symptom improvement during the early sessions of therapy, credit this improvement to the clinician, and thus feel a closer alliance. The child may then continue to experience symptom improvement through better investment and motivation in the remainder of treatment.

Adult psychotherapy process researchers have attempted to disentangle these relationships between early symptom change, early therapeutic alliance, and subsequent outcomes. In these studies with adults, therapeutic alliance predicted therapeutic outcome even while controlling the effects of prior symptomatology (Arnow et al., 2013; Barber, Connolly, Crits-Christoph, Gladis, & Siqueland, 2009; Falkenström, Granström, & Holmqvist, 2013; Zuroff & Blatt, 2006), though contradictory findings have been reported as well (cf. Feeley et al., 1999, where no significant associations were found between alliance and outcome, possibly due to low power). Unfortunately, comparable studies of the relationship between early alliance and symptomatology are nearly absent from the youth psychotherapy process literature. Nearly all extant studies either measure alliance at later sessions or measure alliance and outcome only at infrequent intervals (i.e., pre-/posttreatment, etc.), thus not addressing the role of alliance and symptom change during early sessions (Bertrand et al., 2013; Bourion-Bedes et al., 2013; Guzder, Bond, Rabiau, Zelkowitz, & Rohar, 2011; Hogue et al., 2006; Kazdin & Durbin, 2012; Keeley, Geffken, Ricketts, McNamara, & Storch, 2011; Liber et al., 2010; Marcus, Kashy, Wintersteen, & Diamond, 2011).

More recent studies conducted by Chiu et al. (2009) and Marker, Comer, Abramova, and Kendall (2013) employed prospective designs that controlled for initial severity and included analyses exploring the direction of effect of the alliance–outcome relationship. In both studies, results demonstrated a significant association between early alliance and later symptom severity while controlling for initial severity. However, whereas Chiu et al. found no significant associations between prior symptom change and alliance later in treatment, Marker et al. found some evidence of reciprocal effects between alliance and symptom improvement. It is possible that reciprocal effects were not found by Chiu et al. because their assessments of alliance and symptomatology did not address the same time points. Whereas Chiu et al. assessed alliance at both early and later periods throughout treatment (i.e., Sessions 2, 4, 8, and 10), they measured symptomatology only at pre-, mid-, and posttreatment, reducing the ability to draw conclusions about early changes in symptomatology. When Marker et al. assessed both alliance and symptoms concurrently at all sessions, they found evidence of reciprocal effects of alliance and symptomatology across treatment; however, Marker et al. did not explore the role of early alliance or symptoms specifically. Although still important first steps in the exploration of the relationship between alliance and outcome in youth psychotherapy, these studies could not definitively explore the directionality of effects early in treatment. Furthermore, these studies explored alliance with predominantly younger children in the context of anxiety disorder treatment. Studies suggest that comorbid depressive symptomatology may adversely affect therapeutic alliance (Chu, Skriner, & Zandberg, 2013), and meta-analytic findings have suggested that alliance’s influence may be less robust in older youth (McLeod, 2011). As therapeutic alliance may function differently in treatment with depressed adolescents, studies exploring the directionality of effects between therapeutic alliance and early treatment outcome in adolescents with depression are critically needed.

Given the current state of the research, this project examined a series of path analyses, exploring whether early therapeutic alliance predicted subsequent depression symptoms (after controlling for pretreatment depression level), whether pretreatment symptomatology predicted subsequent therapeutic alliance, or if a reciprocal effects model was best suited to the data. Using a prospective autoregressive cross-lag modeling approach helps to disentangle the directionality and relative influence of the associations of early therapeutic alliance and symptomatology and allows direct comparison between nested models of competing effects. Based on findings from Chu et al. (2013), Chiu et al. (2009), and Marker et al. (2013), we hypothesize that a model wherein early therapeutic alliance predicts subsequent symptomatology (even after controlling for pretreatment levels of symptoms) will provide a significantly better fit to the data than a model wherein early symptomatology predicts alliance. We also conduct exploratory analyses to determine if reciprocal effects provide a superior fit to the data.

METHOD

Participants

Ninety-one adolescents were referred by school psychologists, social workers, school nurses, and guidance counselors from four urban public high schools in the Rocky Mountain west region of the United States; 83 agreed to participate (91% consent rate). Youth were referred if school-based personnel detected symptoms of depression in routine academic or clinical assessments. No incentives or rewards were offered for participation beyond treatment.

Based on structured interviews with the Diagnostic Interview Scale for Children (C-DISC; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000), 54 adolescents met diagnostic criteria for at least one depressive disorder. Eight adolescents were excluded because they failed to meet criteria for a depressive disorder, presented with an exclusionary disorder (bipolar or psychotic disorder), or were currently taking psychotropic medication; an additional eight adolescents were excluded from the present analyses due to treatment attrition prior to Session 4. Analysis of variance showed no significant differences between those completing and those attriting in gender, χ2(1, 45)=0.05, p=.82; race, F(1, 45)=.61, p=.44; pretreatment Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score, F(1, 45)=.13, p=.72; diagnosis, χ2(4, 45)=1.60, p=.81; number of comorbid diagnoses, F(1, 45)=1.46, p=.23; or first-session therapeutic alliance, F(1, 31)=.03, p=.88.

The resulting sample of 38 adolescents was included based on a C-DISC diagnosis of major depressive disorder (n = 28), dysthymic disorder (n = 7), or depressive disorder not otherwise specified (n =3). Approximately 38.5% of the sample had no comorbid diagnoses, 35.9% had one comorbid diagnosis, and 25.7% had two or more comorbid diagnoses. Comorbid diagnoses included conduct disorder (25.6%), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (12.8%), social anxiety disorder (12.8%), and generalized anxiety disorder (5.1%). The sample was 63.2% female (n = 24) and 36.8% male (n = 14), was between the ages of 14 and 18 (M = 15.89, SD = 1.25), and consisted of 63.2% Caucasian and 36.8% ethnic minority youth, with Latino/a (21.1%) and African American (10.5%) youth composing the bulk of the ethnic minority sample. The diversity represented was comparable to the ethnic/racial composition of the local metropolitan area (34.7%; U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). Participants’ socioeconomic status was predominantly middle-class (Mdn = 40.00, SD = 24.20; Hollingshead, 1957).

Measures

Computerized Diagnostic Interview Scale for Children 4.0

The mood, anxiety, and disruptive behavior modules (i.e., major depressive disorder/dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and conduct disorder) of the C-DISC were administered to adolescents by a trained master’s-level clinician. The C-DISC demonstrates good reliability and criterion validity for identifying psychiatric disorders among youth (Shaffer et al., 2000). The C-DISC was used to screen adolescents for inclusion and exclusion disorders at pretreatment.

Beck Depression Inventory

The BDI (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961) is a 21-item self-report measure of depression that was used to assess youth’s early symptom change. The measure assesses for the presence of a wide range of depression symptoms in the previous 2 weeks. Total scores on the BDI can range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. The BDI was the most widely used dimensional measure of depression with adults and adolescents at the start of the study (Beck, Steer, & Garbín, 1988) and demonstrates good psychometric properties (Cronbach’s α = 0.88). A significant body of research supports the use of the BDI with adolescents (Dolle et al., 2012). The measure was collected at pretreatment, posttreatment, and after Sessions 4, 8, and 12.

Alliance Observation Coding System

The Alliance Observation Coding System (AOCS; Karver et al., 2007) is an observational coding system for assessing the therapeutic alliance between a therapist and a youth client. Therapist–youth interactions are observed and coded in 15-min segments within sessions (Sessions 1 and 4). The AOCS consists of 10 observational items and four additional items. The 10 observational items include viewing the therapist as an advocate, comfort in sharing experiences, being receptive to feedback, feeling understood or validated by the therapist, valuing the therapist and/or therapy, feeling positive affect toward the therapist, feeling comforted by the therapist after distress, dysynchrony between client and therapist, negative client reactions to the therapist, and client interruptions of the therapist. The first seven observational items contained both positive and negative indicators of alliance and were coded on a bipolar 5-point scale of frequency of occurrence from 1 (more negative indicators than positive) to 5 (many more positive indicators than negative). The final three observational items contained only negative indicators of alliance and were coded on a unipolar 5-point scale of frequency from 1 (does not perform the behavior) to 5 (performs the behavior six or more times). The four additional items are an overall global rating of alliance, intensely positive client responses, intensely negative client responses, and dominance of conversation by client or therapist. The AOCS has demonstrated high interrater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = 0.84), internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .92), and validity in youth populations (Karver et al., 2008).

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the university and school district Institutional Review Boards prior to initiation of the project.

Pretreatment assessment

Adolescent patients were identified through routine academic or clinical assessments by school-based health or mental health clinicians. Identified adolescents were informed of the school-based treatment for depression by school psychologists or social workers. Parent and adolescent consent and assent for services and research participation were obtained by school personnel prior to referral to the research team for screening. Adolescents were screened for diagnostic eligibility by a master’s-level clinical evaluator via an intake interview including the C-DISC. The BDI was also administered during this session to determine pretreatment depression levels.

Treatment

Eight therapists with doctoral degrees in psychology delivered the treatment, which consisted of a 12-session, manualized cognitive-behavior treatment adapted for adolescents (Crisp, Gudmundsen, & Shirk, 2006; Rosselló & Bernal, 1999). The protocol was modified slightly by elaborating specific components, including additional examples in the manual, and by adding a complementary workbook for adolescent patients. As in the original protocol, the treatment consisted of three components: a thought module focused on identification of automatic thoughts and cognitive restructuring, an action module focused on coping strategies and behavioral activation, and an interpersonal module focused on social support and problem solving. Therapists attended a day-long workshop to train in the protocol and conducted a practice case under clinical supervision. Therapists received 1-½ hr of weekly group supervision by a licensed psychologist with extensive experience in CBT.

Adolescents who met study criteria were assigned to a therapist for school-based treatment; youth who did not meet criteria were provided with referrals. Therapists arranged treatment appointments with adolescents through school-based clinics. For each patient treated, therapists were provided the depression diagnosis, comorbid diagnoses, and all information pertaining to suicidal risk. All sessions were audio-recorded, and tapes from Sessions 1 and 4 were used to code therapeutic alliance. The BDI was administered at Session 4 by therapists.

Treatment fidelity was measured based on the presence or absence of session-by-session agenda items and required subcomponents. Coders listened to audiotaped sessions and rated fidelity using checklists created and used by the manual authors in their studies of CBT for adolescent depression (for more information, see Crisp et al., 2006). Based on a review of a random sample of 25% of therapy sessions, treatment was delivered with a high degree of fidelity with 83% of prescribed components delivered.

Training independent raters

Independent raters were bachelor’s- and master’s-level students in psychology extensively trained to code therapeutic alliance based on the audiotapes of therapy sessions. Training began with a workshop to review and discuss the AOCS manual. Next, a series of several group coding sessions were conducted, wherein trainees would listen to 15-min segments of tapes of increasing coding difficulty, provide their ratings on items, and then discuss their ratings with each other and a trainer with experience in the AOCS until consensus was achieved. After several group coding trainings (and once a high degree of reliability was achieved during group sessions), each coder was required to independently rate the therapeutic alliance on a sampling of previously unheard training audiotapes (not used in the current study). Training tapes were deliberately chosen to represent examples of both high and low therapeutic alliance. For the purposes of training, raters coded five complete sessions in 15-min segments (a minimum of 15–20 segments) and were required to achieve a criterion level of interrater reliability (ICC > 80) with already established coding trainers in order to participate in coding for the study.

AOCS coding procedure

Once trained, coders would be assigned audiotapes to code using the AOCS. Coders would rate each therapeutic alliance item after each 15-min segment of an audiotaped therapy sesssion. Average ratings across all items for each segment of a full session were averaged into a total alliance score for each session. Interrater reliability was checked monthly, and raters participated in coding meetings to discuss and problem solve coding difficulties. Within-rater reliability was checked after half of the tapes were coded and again after the second half were completed. Both interrater reliability and within-rater reliability were found to be acceptable for all coders (all ICCs > 0.70, with the majority between 0.80 and 0.90).

Statistical analyses

All 38 participants included in statistical analyses had complete data for pretreatment assessment and Sessions 1–4 of treatment. Before proceeding to modeling, all data were screened for deviations from statistical assumptions; none were found. Next, we examined the extent of within-therapist clustering to determine whether this clustering variable warranted inclusion in analyses.1 The cluster variable (therapists) had little impact on the outcome variables (Alliance, BDI), as indicated by intraclass coefficients and correlations between therapists and variables at either time point, which were all close to zero (MICC = 0.13, Mr = 0.04). Furthermore, a multivariate analysis of variance found no significant differences of therapist across any of the outcome variables, F(24, 104) = 0.76, p = .77. As such, it was decided that accounting for the clustering variable of therapist was unnecessary, and therefore was not included in subsequent analyses so as to keep the models as parsimonious as possible.

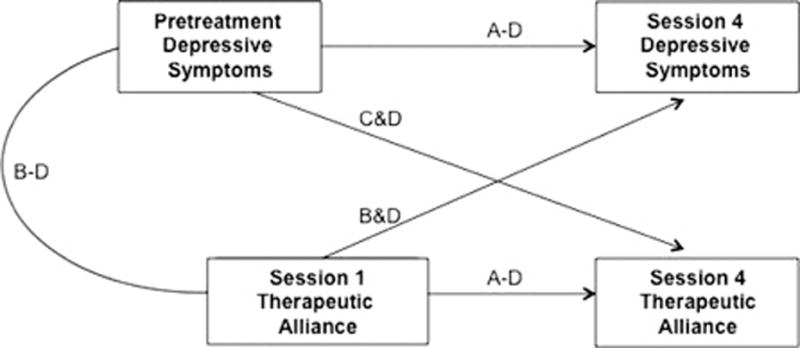

Structural equation modeling using Proc Calis in SAS (version 9.3) was used to test paths of reciprocal association between pretreatment depressive symptomatology, first-session therapeutic alliance, and alliance and depressive symptomatology as measured at Session 4. As it is usually recommended to compare competing models to test several assumptions about the directions of effects when testing cross-lagged models in structural equation modeling (Anderson, 1987), four different nested models were ran (see Figure 1), all using maximum likelihood estimation.

FIGURE 1.

Paths included in tested models. Note: A = Paths tested in the baseline no relationship between alliance and symptomatology model; B = Paths tested in the unidirectional early alliance driving symptomatology model; C = Paths tested in the unidirectional early symptomatology driving alliance model; D = Paths tested in the bidirectional reciprocal influence model.

Model A represented a baseline model wherein stability within constructs was tested, but no relationships across domains were estimated (i.e., no relationship between alliance and symptomatology model, or pretreatment symptomatology predicting symptomatology at Session 4 and Session 1 alliance predicting alliance at Session 4 with no cross-lagged paths included). Model B represented a unidirectional effects model wherein first-session therapeutic alliance and pretreatment depression symptomatology predicted depressive symptoms as reported at Session 4 (i.e., early alliance driving symptomatology model, controlling for pretreatment depression symptoms). Model C represented the opposing unidirectional effects model, wherein first-session therapeutic alliance and pretreatment depression symptomatology predicted therapeutic alliance at Session 4 (i.e., early symptomatology driving alliance model, controlling for first-session alliance). Finally, Model D represented a bidirectional effects model wherein pretreatment depression symptomatology and first-session therapeutic alliance predicted both depressive symptoms and therapeutic alliance at Session 4 (e.g., reciprocal influence model, or auto-regressive path analysis). Chi-square difference tests were used to compare competing models to determine (a) whether a model with early therapeutic alliance predicting subsequent symptoms would provide a significantly better fit to the data than a model with early symptomatology predicting alliance, and (b) whether the inclusion of reciprocal cross-lagged effects resulted in significant improvement in model fit over unidirectional effects.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics and correlations of the main variables are presented in Table 1. The sample had pretreatment depression scores ranging from 11 to 52 (possible range = 0–63), with an average score of 30.32 representing severe depressive symptomology. By Session 4, these scores declined significantly, t(37) = 6.32, p < .001; youth reported scores ranging from 5 to 34 with an average score of 21.18 representing mild to moderate depressive symptomatology. Therapeutic alliance as reported at Session 1 was high (ranging from 3.87 to 4.83; possible range = 0–5; M = 4.39) and remained relatively stable at Session 4 (ranging from 3.28 to 4.78; possible range = 0–5; M = 4.27), t(37) = 1.93, p .06.

TABLE 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Between Variables

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pretreatment BDI | 30.32 (9.59) | — | .57** | .17 | .24 |

| 2. BDI at Session 4 | 21.18 (9.58) | — | .38* | .03 | |

| 3. Alliance at Session 1 | 4.39 (0.24) | — | .24 | ||

| 4. Alliance at Session 4 | 4.27 (0.35) | — |

Note: Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores range from 0–63, with 0–13 considered minimal, 14–19 mild, 20–28 moderate, and 29–63 severe depressive symptomology. Alliance scores range from 1–5, where 5 is the highest level of therapeutic alliance. N = 38.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Fit indices for the four models tested are presented in Table 2. Model A, the baseline no relationship between alliance and symptomatology model, showed poor model fit2 (see Table 2), suggesting that stability within constructs alone was not a good fit to the data and that adding relationships between the alliance and symptom domains may enhance model fit. As such, the unidirectional models were run. Model B, the early alliance driving symptomatology model, showed moderate model fit on all fit indices other than the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; see Table 2); the inflation of RMSEA may have been due to this index’s correction for parsimony, penalizing the model for its near saturation. Chi-square difference tests showed that Model B provided a significantly better fit than the baseline model, Δχ2(1) 4.9, p < .05. This suggests that Model B is superior to the baseline model, in which alliance and symptomatology were not related to each other, but that a model of early alliance affecting subsequent symptomatology may not account for all variance present in the data. The competing unidirectional Model C, the early symptomatology driving alliance model, showed poor model fit (see Table 2) and was not significantly different than the baseline model, Δχ2(1) = 1.7, p =.20. This suggests that a model of early symptomatology affecting subsequent therapeutic alliance is not supported and that a model with early alliance predicting subsequent symptoms (Model B) is superior to a model with early symptoms predicting subsequent alliance (Model C).

TABLE 2.

Fit Indices for the Four Tested Models of Alliance and Symptom Change

| Model | Type | df | χ2 | SRMR | RMSEA | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A: No Relationship Between Alliance and Symptomatology | Baseline | 3 | 8.44, p < .05 | .11 | .22 | .73 |

| Model B: Early Alliance Driving Symptomatology | Unidirectional | 2 | 3.54, p = .17 | .07 | .14 | .92 |

| Model C: Early Symptomatology Driving Alliance | Unidirectional | 2 | 6.78, p < .05 | .10 | .25 | .76 |

| Model D: Reciprocal Influence | Bidirectional | 1 | 1.88, p = .17 | .05 | .15 | .96 |

Note: N = 38. Final selected model is presented in bold. SRMR = standardized root square mean residual; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CFI = comparative fix index.

Last, the bidirectional Model D, or reciprocal influence model, was computed. Model D had adequate fit on all fit indices other than RMSEA (see Table 2); like in Model B, inflation of RMSEA is likely due to this index’s correction for parsimony, penalizing the model for near saturation. The bidirectional model demonstrated significantly better fit than the baseline model, Model A, Δχ2(2) = 6.6, p < .05, and the early symptomatology driving alliance model, Model C, Δχ2(1) = 4.9, p < .05, but did not show significant improvement over the early alliance driving symptomatology model, Model B, Δχ2(1) = 1.6, p = .20. As Model D did not show significantly better fit than Model B, the more parsimonious unidirectional early alliance driving symptomatology model was selected as our final model.3

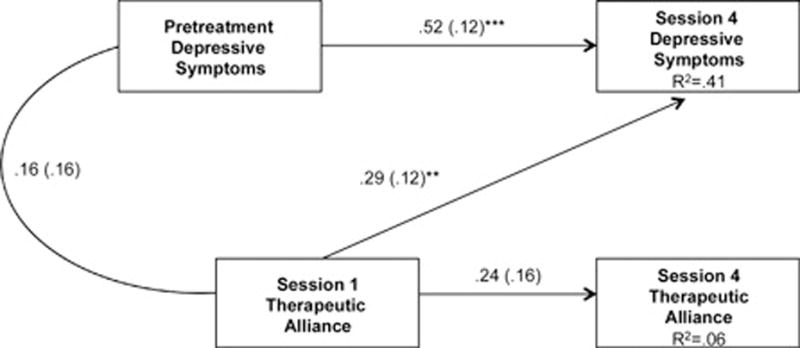

Standardized path estimates and variable R2 values for Model B are presented in Figure 2. The early alliance driving symptomatology model explained 41% of the variance in depressive symptoms reported at Session 4 but only 6% of the variance in therapeutic alliance at Session 4. Strength of stability paths from baseline to Session 4 measurements of the constructs implied that, although depressive symptoms at pretreatment were a significant predictor of subsequent depression symptoms at Session 4 as expected (0.52, SE=0.13; t=4.06, p < .001), first-session therapeutic alliance was also a strong and significant predictor of depression symptoms as reported at Session 4 (11.63, SE = 5.08; t = 2.29, p < .05).

FIGURE 2.

Standardized path estimates for the final selected model, Model B: the unidirectional early alliance driving symptomatology model. Note: Standard errors are listed in parentheses. χ2(2, N = 38) = 3.54, p = .17; standardized root square mean residual = 0.066, root mean square error of approximation = 0.144, comparative fix index = 0.922. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

To further elucidate magnitude of effect, a median split was applied to group participants based on high or low alliance at Session 1, and a small but insignificant difference between groups was found in BDI change from Sessions 1 to 4 (Low Alliance: M=8.35, SD=10.01 vs. High Alliance: M=12.86, SD=9.95), F(1, 38)=1.92, p=.18; . Although this effect was not statistically significant, the effect size was moderate, suggesting that insignificance may have resulted due to inadequate power to detect small to medium effects with small sample sizes. Given that a 4.5-point difference between groups in BDI change is not of negligible clinical significance (Seggar, Lambert, & Hansen, 2002) and dichotomizing continuous variables results in a reduction of power (cf. Irwin & McClelland, 2003; MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker, 2002), a continuous measure of relationship magnitude was also explored. When first-session alliance was regressed on the change in BDI scores across Sessions 1–4, a significant large effect was found, F(1, 30)=38.38, p < .001, . These findings are in concert with the standardized path estimate reported in the final model, where a path estimate of .29 from Session 1 therapeutic alliance to Session 4 depression symptoms represents a moderate effect.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we explored the directionality of effects between therapeutic alliance and depressive symptomatology early in treatment in a sample of 38 adolescents receiving cognitive-behavioral therapy for a primary depressive disorder through school-based mental health clinics. Using a prospective autoregressive cross-lag modeling approach, we directly compared whether early therapeutic alliance predicted subsequent depression symptoms controlling for pretreatment depression level (as suggested by Chiu et al., 2009; Chu et al., 2013; Marker et al., 2013), or whether pretreatment symptomatology predicted subsequent therapeutic alliance (as suggested by Crits-Christoph et al., 2006). In addition, we examined whether a reciprocal effects model was best suited to the data.

Data from this sample suggested that early therapeutic alliance drives subsequent symptomatology and not vice versa, even after controlling for pretreatment symptom levels. Models wherein first-session alliance predicted depressive symptoms at Session 4 (Models B and D) showed good model fit, whereas models where this path was not included (Models A and C) showed extremely poor model fit. These findings suggest that therapeutic alliance plays a critical role in early gains in youth psychotherapy and support the conclusions of adult studies such as Zuroff and Blatt (2006), as well as youth studies by Chu et al. (2013), Chiu et al. (2009), and Marker et al. (2013). These findings also directly contradict those who state that therapeutic alliance is merely a result of early symptom change (e.g., Crits-Christoph et al., 2006), as pretreatment depressive symptoms showed no association with therapeutic alliance at either the first (p=.69) or fourth session (p=.19).

Although alliance quality was not experimentally manipulated, these findings suggest that early alliance impacts early symptom change. This finding of alliance driving symptomatology, rather than symptomatology driving alliance, remained unchanged even in the less parsimonious reciprocal effects model (Model D) that accounted for transactional influences between the two domains, where the alliance predicting symptoms path remained significant (path estimate=0.29, p < .01), whereas the symptoms predicting alliance path did not approach significance (path estimate=0.21, p= .19). However, these data do not preclude the possibility of reciprocal effects between early alliance and symptomatology. The model that accounted for reciprocal influences between the domains still maintained excellent model fit, suggesting that the addition of a pathway from pretreatment symptomatology to therapeutic alliance at session four did not result in misspecification of the data. However, the reciprocal effects model (Model D) was not selected because it did not achieve significant improvements in fit over the more parsimonious unidirectional early alliance driving symptomatology model (Model B), and the pathway added in Model D (from pretreatment depressive symptoms to therapeutic alliance at Session 4) did not achieve significance (p = .19). Nevertheless, as our sample size was small (n = 38), it is likely that our analyses were underpowered to detect smaller effects; power analysis suggests that a sample nearly double the size of this one (n = 83) would be the minimum necessary to detect small effects given the specifications of Model D (Cohen, 1988; Soper, 2014). As such, it is entirely possible that there are small transactional influences between therapeutic alliance and symptomatology but that only the effect of alliance on symptoms had a large-enough effect size to reach statistical significance in this sample. Therefore, tests of reciprocal influence should be replicated in larger samples.

This study had some limitations, most notably the previously mentioned small sample that limited us from definitively determining if reciprocity of effects existed. Furthermore, the small sample size precluded the possibility of adequate power and free parameters for model testing including therapist as a clustering variable (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Although preliminary analyses suggest that no significant differences existed between therapists and that therapist did not influence the outcome variables in a meaningful way, future studies should include larger sample sizes so that smaller, more nuanced therapist effects can be explored, such as how the match of therapist/client ethnicity or gender may affect therapeutic alliance and symptom improvement.

Likewise, the size and constituency of the sample may limit generalizability, and thus one must be cautious of extending conclusions to clients of dissimilar age or diagnosis, youth clients receiving non-CBT treatments, or youths receiving services in a different treatment setting, as these factors may affect therapeutic alliance (McLeod, 2011). Future studies should conduct similar prospective analyses of the role of early alliance and symptomatology in larger samples with different client characteristics to determine the generalizability of these results.

A further limitation of this study is that pretreatment changes in symptomatology from screening to Session 1 were not assessed. Unfortunately, due to the design of the study, it cannot be ruled out that some of the participants may have experienced pretreatment gains that could potentially influence subsequent relationships between alliance and symptomatology. Similar studies such as Gaynor et al. (2003) have found that approximately 25% of a sample of depressed adolescents experienced pretreatment gains between intake and the first session. Thus, if analogous rates existed in our sample, the majority of participants would not experience pretreatment gains, but a smaller proportion may have a combination of pretreatment and early treatment symptom change influencing subsequent relationships between therapeutic alliance and symptomatology. Whereas more recent studies with depressed adolescents have suggested that a more positive therapeutic alliance predicted greater subsequent symptom improvement even after controlling pretreatment symptom change (Reyes, 2013), this cannot be empirically examined with this data. However, the covariance between pretreatment symptoms and Session 1 therapeutic alliance was included in all relevant models and was found to be both small in magnitude and statistically insignificant, suggesting that pretreatment symptoms may not have a particularly strong relationship with Session 1 alliance.

A further complication of the study design is that participants experienced different wait times before their initial meeting with their therapist, mostly due to the logistics of screening and obtaining consent for treatment in the schools. Whereas the majority of participants were seen within 1 week of screening, there was substantial variability (range of approximately 4 days to more than 20 days). It is possible that varying wait times between screening and a participant’s first session may have somehow influenced subsequent relationships, although this is less likely given that no significant relationships were present between wait time and any of the variables included in the models. As such, although it is entirely possible that pretreatment gains or wait time may be influencing the therapeutic alliance and symptomatology relationship, it is also unlikely that pretreatment gains and wait time account for much variance in the relationships reported. These factors should be explored further in future studies.

It also should be noted that the changes in therapeutic alliance across sessions are relatively small in magnitude; however, these changes are comparable to alliance changes reported in other studies (i.e., Kazdin et al., 2006; Ormhaug, Jensen, Wentzel-Larsen, & Shirk, 2014), suggesting that therapeutic alliance may be fairly stable over the course of therapy. Furthermore, even studies that have found relatively small mean changes in alliance over time across entire samples have found these changes to be clinically meaningful, in that they predict symptom change (Bickman et al., 2012). Taken together, the fact that even small variations in therapeutic alliance had a significant effect on subsequent symptomatology suggests that therapeutic alliance may be an important influence on early symptom change.

Despite limitations, this study also had numerous strengths. First, the study used an observational alliance coding system that has been well validated with youth and adolescents, thereby avoiding the pitfalls that sometimes come with survey-based measurement of alliance (Shirk & Karver, 2003). Second, the sample was relatively ethnically and racially diverse and utilized a naturalistic treatment setting, which may enhance generalizability of results. Last and most important, this study was the first study of its kind to explore the role of early therapeutic alliance and symptomatology in a sample of depressed adolescents and utilized a strong study design and statistical analysis plan that allowed for exploration of competing models of these relationships.

In conclusion, study results clearly denote the importance of therapeutic alliance early in youth psychological treatment, and specifically imply that therapeutic alliance in early sessions with adolescents is critical to fostering early gains in depressive symptomatology. Knowing alliance’s subsequent effect on youth outcomes, clinicians should increase effort to foster a strong relationship in early sessions. Likewise, additional research should be conducted on the reciprocal effects of therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in adolescence, including how to best enhance early alliance to maximize therapeutic gains.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This study was supported by Award #R21 MH065988 to Dr. Shirk, and Dr. Labouliere was supported as a postdoctoral fellow by Award #T32 MH16434-34, both from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) at the National Institutes of Health. The contents of the article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIMH.

Footnotes

Although including therapist as a clustering variable would be indicated in larger studies, such a model is too complex for studies with smaller samples. For three-level nested analyses, it is typically recommended to have a minimum of 100 or more participants at the second level, as the second level determines power (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Furthermore, having only four indicator variables nested within so few higher level variables (i.e., 38 youth within eight therapists) would result in too few free parameters available, making it unlikely that analyses would converge or provide reliable information (Bollen, 1989; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), especially as the number of patients seen by each therapist was highly variable (mode = 3, range = 21–11). Instead, we sought to determine whether the clustering effect of therapist could potentially bias results, and we found that the cluster variable had little impact on the outcome variables.

Adequacy of model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999; MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996; McDonald & Ho, 2002) was demonstrated by a low and nonsignificant chi-square value, standardized root mean square residual < .08, RMSEA < .08, and comparative fit index < .90.

The authors chose to utilize cross-lagged path analyses where Time 1 scores were statistically covaried rather than utilizing change scores, because change scores can be unreliable in small samples with few measurements and regression-based covarying within a structural equation modeling framework may better account for this error variance (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). To determine whether the use of change scores rather than statistically covarying would alter conclusions, all models were also computed using change scores. Neither fit indices nor the magnitude and significance of relationships within the models were altered by the use of change scores.

Contributor Information

Christa D. Labouliere, Division of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, New York State Psychiatric Institute at Columbia University Medical Center

J. P. Reyes, Outpatient Department, New York-Presbyterian Hospital – Westchester Division

Stephen Shirk, Department of Psychology, University of Denver.

Marc Karver, Department of Psychology, University of South Florida.

References

- Anderson JC. An approach for confirmatory measurement and structural equation modeling of organizational properties. Management Science. 1987;33:525–541. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.33.4.525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnow BA, Steidtmann D, Blasey C, Manber R, Constantino MJ, Klein DN, Kocsis JH. The relationship between the therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in two distinct psychotherapies for chronic depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:627–638. doi: 10.1037/a0031530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber JP, Connolly MB, Crits-Christoph P, Gladis L, Siqueland L. Alliance predicts patients’ outcome beyond in-treatment change in symptoms. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, S. 2009:80–89. doi: 10.1037/1949-2715.s.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbín MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand K, Brunelle N, Richer I, Beaudoin I, Lemieux A, Ménard JM. Assessing covariates of drug use trajectories among adolescents admitted to a drug addiction center: Mental health problems, therapeutic alliance, and treatment persistence. Substance Use & Misuse. 2013;48:117–128. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.733903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L, de Andrade ARV, Athay MM, Chen JI, De Nadai AS, Jordan-Arthur BL, Karver MS. The relationship between change in therapeutic alliance ratings and improvement in youth symptom severity: Whose ratings matter the most? Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012;39:78–89. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0398-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K. Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York, NY: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bourion-Bedes S, Baumann C, Kermarrec S, Ligier F, Feillet F, Bonnemains C, Kabuth B. Prognostic value of early therapeutic alliance in weight recovery: A prospective cohort of 108 adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52:344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AF, Simmonds JG. Therapist perspectives on the therapeutic alliance with children and adolescents. Counseling Psychology Quarterly. 2011;24:195–209. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2011.620734. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu AW, McLeod BD, Har K, Wood JJ. Child–therapist alliance and clinical outcomes in cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:751–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu S, Skriner LC, Zandberg LJ. Trajectory and predictors of alliance in cognitive behavioral therapy for youth anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;43:721–734. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.785358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CM. Irreducibly human encounters: Therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in child and adolescent psychotherapy. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy. 2013;12:228–243. doi: 10.1080/15289168.2013.822751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp HL, Gudmundsen GR, Shirk SR. Transporting evidence-based therapy for adolescent depression to the school setting. Education and Treatment of Children. 2006;29:287–309. [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Gibbons MBC, Hearon B. Does the alliance cause good outcome? Recommendations for future research on the alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2006;43:280–285. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromley T, Lavigne JV. Predictors and consequences of early gains in child psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2008;45:42–60. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.45.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgadillo J, McMillan D, Lucock M, Leach C, Ali S, Gilbody S. Early changes, attrition, and dose–response in low intensity psychological interventions. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;53:114–130. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolle K, Schulte-Körne G, O’Leary AM, von Hofacker N, Izat Y, Allgaier AK. The Beck Depression Inventory-II in adolescent mental health patients: Cut-off scores for detecting depression and rating severity. Psychiatry Research. 2012;200:843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenström F, Granström F, Holmqvist R. Therapeutic alliance predicts symptomatic improvement session by session. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2013;60:317–328. doi: 10.1037/a0032258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeley M, DeRubeis RJ, Gelfand LA. The temporal relation of adherence and alliance to symptom change in cognitive therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:578–582. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.67.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florsheim P, Shotorbani S, Guest-Warnick G, Barratt T, Hwang WC. Role of the working alliance in the treatment of delinquent boys in community-based programs. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:94–107. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2901_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor ST, Weersing VR, Kolko DJ, Birmaher B, Heo J, Brent DA. The prevalence and impact of large sudden improvements during adolescent therapy for depression: A comparison across cognitive-behavioral, family, and supportive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:386–393. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J. Annotation: The therapeutic alliance—A significant but neglected variable in child mental health treatment studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:425–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzder J, Bond S, Rabiau M, Zelkowitz P, Rohar S. The relationship between alliance, attachment and outcome in a child multi-modal treatment population: Pilot study. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;20:196–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Dauber S, Stambaugh LF, Cecero JJ, Liddle HA. Early therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome in individual and family therapy for adolescent behavior problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:121–129. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.74.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Two factor index of socioeconomic status. New Haven, CT: Yale University; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin JR, McClelland GH. Negative consequences of dichotomizing continuous predictor variables. Journal of Marketing Research. 2003;40:366–371. doi: 10.1509/jmkr.40.3.366.19237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karver MS, Handelsman J, Labouliere CD, Shirk SR, Day M, Fields S. Rater’s manual for the alliance observation checklist—Text revision. Tampa: University of South Florida; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Karver M, Shirk S, Handelsman JB, Fields S, Crisp H, Gudmundsen G, McMakin D. Relationship processes in youth psychotherapy: Measuring alliance, alliance-building behaviors, and client involvement. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2008;16:15–28. doi: 10.1177/1063426607312536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Durbin KA. Predictors of child–therapist alliance in cognitive-behavioral treatment of children referred for oppositional and antisocial behavior. Psychotherapy. 2012;49:202–217. doi: 10.1037/a0027933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Whitley M, Marciano PL. Child–therapist and parent–therapist alliance and therapeutic change in the treatment of children referred for oppositional, aggressive, and antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:436–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley ML, Geffken GR, Ricketts E, McNamara JPH, Storch EA. The therapeutic alliance in the cognitive behavioral treatment of pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:855–863. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Comer JS, Marker CD, Creed TA, Puliafico AC, Hughes AA, Hudson J. In-session exposure tasks and therapeutic alliance across the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:517–525. doi: 10.1037/a0013686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Ollendick TH. Setting the research and practice agenda for anxiety in children and adolescence: A topic comes of age. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2004;11:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s1077-7229(04)80008-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ. Early response in psychotherapy: Further evidence for the importance of common factors rather than “placebo effects”. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61:855–869. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liber JM, McLeod BD, Van Widenfelt BM, Goedhart AW, van der Leeden AJM, Utens EMWJ, Treffers PDA. Examining the relation between the therapeutic alliance, treatment adherence, and outcome of cognitive behavioral therapy for children with anxiety disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:172–186. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.1.2.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:19–40. doi: 10.1037//1082-989x.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus DK, Kashy DA, Wintersteen MB, Diamond GS. The therapeutic alliance in adolescent substance abuse treatment: A one-with-many analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:449–455. doi: 10.1037/a0023196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marker CD, Comer JS, Abramova V, Kendall PC. The reciprocal relationship between alliance and symptom improvement across the treatment of childhood anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42:22–33. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.723261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis MK. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:438–450. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.68.3.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, Ho MHR. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological methods. 2002;7:64–82. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD. Relation of the alliance with outcomes in youth psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:603–616. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlinsky DE, Ronnestad MH, Willutzki U. Fifty years of psychotherapy process-outcome research: Continuity and change. In: Lambert MJ, editor. Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. New York, NY: Wiley; 2004. pp. 307–389. [Google Scholar]

- Ormhaug SM, Jensen TK, Wentzel-Larsen T, Shirk SR. The therapeutic alliance in treatment of traumatized youths: Relation to outcome in a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82:52–64. doi: 10.1037/a0033884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes JP. Examining the alliance-outcome relationship: Reverse causation, third variables, and treatment phase artifacts. 2013 Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1493901289). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1493901289?accountid=10226.

- Rosselló J, Bernal G. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal treatments for depression in Puerto Rican adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:734–745. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rynn M, Khalid-Khan S, Garcia-Espana JF, Etemad B, Rickels K. Early response and 8-week treatment outcome in GAD. Depression and Anxiety. 2006;23:461–465. doi: 10.1002/da.20214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seggar LB, Lambert MJ, Hansen NB. Assessing clinical significance: Application to the Beck Depression Inventory. Behavior Therapy. 2002;33:253–269. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(02)80028-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Caporino NE, Karver MS. The alliance in adolescent therapy: Conceptual, operational, and predictive issues. In: Castro-Blanco D, Karver MS, editors. Elusive alliance: Treatment engagement strategies with high-risk adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 59–93. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Gudmundsen G, Kaplinski HC, McMakin DL. Alliance and outcome in cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:631–639. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Karver M. Prediction of treatment outcome from relationship variables in child and adolescent therapy: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:452–464. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Karver MS. Process issues in cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth. In: Kendall PC, editor. Child and adolescent therapy: Cognitive-behavioral procedures. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 465–491. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Karver MS, Brown RB. The alliance in child and adolescent psychotherapy. Psychotherapy. 2011;48:17–24. doi: 10.1037/a0022181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirk SR, Russell RL. Change processes in child psychotherapy: Revitalizing treatment and research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TP, Frick PJ, Kahn RE, Evans LJ. Therapeutic alliance in justice-involved adolescents undergoing mental health treatment: The role of callous-unemotional traits. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health. 2013;12:83–92. doi: 10.1080/14999013.2013.787559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soper DS. A-priori sample size calculator for structural equation models [Software] 2014 Retrieved from http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc3/calc.aspx?id=89.

- Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ. Sudden gains and critical sessions in cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:894–904. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.67.6.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Community Facts. 2000 Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml.

- Zuroff DC, Blatt SJ. The therapeutic relationship in the brief treatment of depression: Contributions to clinical improvement and enhanced adaptive capacities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:130–140. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.74.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]