Abstract

In 2014, FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22, two novel synthetic cannabinoids, were detected in herbal blends in Japan, Russia, and Germany and were quickly added to their scheduled drugs list. Unfortunately, no human metabolism data are currently available, making it challenging to confirm their intake. The present study aims to identify appropriate analytical markers by investigating FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 metabolism in human hepatocytes and confirm the results in authentic urine specimens. For metabolic stability, 1 μM FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 was incubated with human liver microsomes for up to 1 h; for metabolite profiling, 10 μM was incubated with human hepatocytes for 3 h. Two authentic urine specimens from FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 positive cases were analyzed after β-glucuronidase hydrolysis. Metabolite identification in hepatocyte samples and urine specimens was accomplished by high-resolution mass spectrometry using information-dependent acquisition. Both FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 were rapidly metabolized in HLM with half-lives of 12.4 and 11.5 min, respectively. In human hepatocyte samples, we identified seven metabolites for both compounds, generated by ester hydrolysis and further hydroxylation and/or glucuronidation. After ester hydrolysis, FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 yielded the same metabolite M7, fluorobenzylindole-3-carboxylic acid (FBI-COOH). M7 and M6 (hydroxylated FBI-COOH) were the major metabolites. In authentic urine specimens after β-glucuronidase hydrolysis, M6 and M7 also were the predominant metabolites. Based on our study, we recommend M6 (hydroxylated FBI-COOH) and M7 (FBI-COOH) as suitable urinary markers for documenting FDU-PB-22 and/or FUB-PB-22 intake.

Keywords: FDU-PB-22, FUB-PB-22, hepatocyte metabolism, high-resolution mass spectrometry, synthetic cannabinoid

INTRODUCTION

Synthetic cannabinoids (SC) are agonists at endogenous cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors and were initially synthesized as pharmacological probes for investigating the endocannabinoid system and developing potential therapeutic compounds (1, 2). Since the mid-2000s, SC are abused due to psychoactive effects (3), which has resulted in increased numbers of emergency room visits due to psychotic episodes, kidney failure, stroke, myocardial infarctions, and even occasional deaths (4–7).

Because of increased prevalence and health concerns, many SC such as JWH-018, JWH-073, JWH-200, UR-144, XLR-11, AKB-48, AB-PINACA, AB-FUBINACA, AB-CHMINACA, and THJ-2201 were scheduled in the USA, Japan, and most European countries (8). A total of 858 SC were scheduled in Japan as narcotics or designated substances as of April 2015 (9). Despite regulations, clandestine laboratories continuously produce structurally diverse compounds to circumvent scheduling legislation. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addition (EMCDDA) reported 30 new SC in 2014 and a 200-fold increase in the number of SC seizures from 2008 to 2013 (10).

Two of the newest SC, FDU-PB-22 (naphthalen-1-yl 1-[(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]-1H-indole-3-carboxylate) and FUB-PB-22 (quinolin-8-yl 1-[(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]-1H-indole-3-carboxylate) (Fig. 1a, b), were first reported by Japanese researchers in 2014 (11, 12). The only difference between FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 is the naphthalene or quinoline ring, respectively, connected to the indole core via an ester bond. The United States Army Criminal Investigation Laboratory (USACIL) reported 16 positive cases of FUB-PB-22 and 6 positive cases of FDU-PB-22 between February and November 2014 (unpublished data). FUB-PB-22 also was detected in Russia in May 2014 (13) and the Mayotte Islands (14). Proliferation of novel psychoactive substances (NPS) is a global challenge; identifying NPS intake and associating specific adverse effects with the causative agent requires rapid elucidation of NPS and their major urinary metabolites because SC are usually extensively metabolized and the parent drug is rarely present in urine (13).

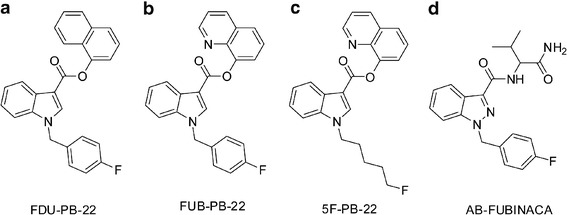

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of FDU-PB-22 (a), FUB-PB-22 (b), 5F-PB-22 (c), and AB-FUBINACA (d)

FUB-PB-22 is the fluorobenzyl analog of PB-22, maintaining the core structure of an indole ring system linked to a quinoline by an ester group, but with the pentyl side chain replaced by a para-fluorobenzyl substituent (FUB). This substituent also was utilized in AB-FUBINACA (Fig. 1d). FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 have identical structures except the replacement of naphthalene with quinoline. Introduction of a nitrogen atom increased the polarity of FUB-PB-22. The predicted logD4 values of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 were 6.37 and 3.07, respectively (predicted by MetaSite software, Molecular Discovery, Pinner, UK). To date, to our knowledge, there are no clinical studies investigating pharmacological and toxicological effects and the pharmacokinetics of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22. The only available data about their effects are found in drug user forums on the internet, for instance, www.drug-forum.com. However, we should be cautious with these data because users are frequently unaware of what compounds they are taking. Drug users also reported paranoia as an adverse effect of FUB-PB-22 (15).

To date, all investigated SC are extensively metabolized in humans and are predominantly excreted as metabolites in urine (16–18), complicating detection as metabolites are initially unknown. Since urine is the most common matrix in clinical, sport doping, or roadside testing, knowledge of human metabolism is essential for developing effective urine testing methods to verify FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 consumption. However, due to the lack of pharmacology, toxicity, and safety data, controlled human pharmacokinetic studies are not yet possible. Although there are no published data for FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22, metabolism studies of their analogs PB-22, 5F-PB-22 (Fig. 1c), and AB-FUBINACA are available (8, 19). PB-22 and 5F-PB-22 underwent extensive ester hydrolysis, followed by oxidative defluorination for 5F-PB-22 (8). The replacement of the fluoropentyl side chain with p-fluorobenzyl may lead to quite different metabolic profiles for FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22, as the p-fluorobenzyl moiety were metabolically stable in AB-FUBINACA (19).

Human hepatocytes were selected, rather than human liver microsomes (HLM), to better simulate a physiological liver environment (20, 21). The hepatocyte incubation model was successful in our previous studies for identifying appropriate markers for AB-FUBINACA (19), AB-PINACA (22), and AH-7921 (23), among others. Two urine samples collected from individuals suspected of driving under the influence of drugs also were analyzed to assess utility of our in vitro conclusions. Metabolite identifications were performed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled to the 5600+ TripleTOF (time-of-flight) high-resolution mass spectrometer (HR-MS). The most dominant human hepatocyte metabolites were compared to urinary metabolites. We propose that these major metabolites will serve as useful urinary markers for identifying FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 intake during future forensic analysis.

We investigated in vitro human metabolism of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 and confirmed our results in authentic urine specimens. The identified optimal urinary markers can be incorporated into screening methods for documenting SC intake, can assist associating observed adverse events with the causative substances, and can provide reference standard manufacturers with the most critical metabolites for their synthesis efforts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and Reagents

FDU-PB-22 (91.93% pure) and FUB-PB-22 (97.68% pure) were kindly provided by the US Drug Enforcement Administration Special Testing and Research Laboratory (Dulles, VA, USA). Diclofenac was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, Canada). Cryopreserved human hepatocytes (10-donor pool), GRO CP, and GRO KHB buffer for hepatocytes, 50-donor pooled HLM, and NADPH-regenerating solutions were acquired from BioreclamationIVT (Baltimore, MD, USA). Red Abalone β-glucuronidase was obtained from Kura Biotec (Puerto Varas, Chile). Acetonitrile and ethyl acetate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and acetic acid, LC-MS grade water, and formic acid from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Isolute (1 mL) supported liquid extraction (SLE+) columns (Biotage, Charlotte, NC, USA) were utilized in sample preparation.

Metabolic Stability Assay in HLM

HLM metabolic stability assays were performed in the same manner as in our previous manuscripts (19, 22). Samples were stored at –80°C until analysis. After thawing and vortexing, samples were centrifuged again; 10 μL supernatant was diluted with 990 μL mobile phase A/B (90:10, v/v) and 10 μL injected for LC-MS/MS analysis.

The chromatographic system consisted of two LC-20ADxr pumps, a DGU-20A3R degasser, a SIL-20ACxr auto-sampler, and a CTO-20A column oven (Shimadzu, Columbia, MD, USA). The Kinetex™ C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm ID, 2.6 μm) was fitted with a KrudKatcher Ultra HPLC in-line filter (0.5 μm × 0.1 mm ID) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). Mobile phases were 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B), and the gradient was 10% B for 0.5 min, ramped to 95% B at 10 min, then held until 12.5 min before re-equilibrating at 10% B for 2.5 min. Total run time was 15 min with a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. Column and autosampler temperatures were 40 and 4°C, respectively.

Data acquisition was performed on a 3200 QTRAP mass spectrometer (SCIEX, Redwood City, CA, USA) with Analyst software (version 1.6) in positive electrospray ionization (+ESI) mode. Ion source parameters were as follows: source temperature, 500°C; ion spray voltage, 4000 V; curtain gas, 30 psi; gas 1, 45 psi; gas 2, 70 psi. Two ion transitions were monitored for FDU-PB-22 (396 → 252; 396 → 109) and FUB-PB-22 (397 → 252; 397 → 109). For FDU-PB-22, declustering potential was 31 V; collision energy was 23 eV (target ion, T) and 47 eV (Qualifier ion, Q). For FUB-PB-22, declustering potential was 36 V; collision energy was 23 eV (T) and 47 eV (Q). Although we did not evaluate linearity, the dynamic range over which the parent compound’s peak areas decreased in HLM was less than 30-fold, and we diluted samples 1:100 before data acquisition to avoid ion saturation; peak areas may not be linear.

Peak areas were plotted against time, and in vitro microsomal half-life (T1/2) and intrinsic clearance (CLint, micr) were calculated (24). Microsomal intrinsic clearance was scaled to whole-liver dimensions yielding intrinsic clearance (CLint). Human hepatic clearance (CLH) and extraction ratio (ER) were calculated without considering plasma protein binding.

Metabolite Profiling in Human Hepatocytes

Hepatocyte incubation was performed as previously described (19, 22). Chemical stability of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 in KHB buffer also was performed (37°C, 3 h) to determine whether metabolites are generated without hepatocytes. Samples were stored at −80°C until analysis.

Samples were thawed and vortexed thoroughly. One hundred microliters of acetonitrile was added to 100 μL aliquot of samples, and the mixture was vortexed, centrifuged at 15,000g (4°C, 5 min), supernatant transferred to a new 10-mL plastic tube, evaporated to dryness under nitrogen at 40°C, and reconstituted in 150 μL mobile phase A/B (80:20, v/v). Fifteen microliters of reconstituted solution was injected for analysis.

The HPLC system consisted of two LC-20ADxr pumps, a DGU-20A5R degasser, a SIL-20ACxr autosampler, and a CTO-20 AC column oven (Shimadzu). Chromatographic separation was achieved on an Ultra Biphenyl column (100 × 2.1 mm ID, 3 μm) equipped with a guard column containing identical packing material. Gradient elution was performed with 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B) at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. Initial gradient conditions were 20% B, held for 0.5 min; then increased to 95% B over 10.5 min, held until 13.0 min; and returned to 20% B at 13.1 min and held until 15.0 min. HPLC eluent was diverted to waste before 2.0 min and after 13.0 min. The column oven and autosampler were maintained at 30 and 4°C, respectively.

Data were acquired on a 5600+ TripleTOF mass spectrometer (SCIEX) in (+)ESI mode. MS data were acquired by information-dependent acquisition (IDA) in combination with multiple mass defect filters (MDF) and dynamic background subtraction (DBS). Ion source parameters were as follows: gas 1, 60 psi; gas 2, 75 psi; curtain gas, 45 psi; source temperature 650°C; ion spray voltage, 4000 V; declustering potential, 80 V; collision entrance potential, 10 V. For IDA experiments, spectra exceeding 100 cps were selected for the dependent MS/MS scan, isotopes within 1.5 Da were excluded, and mass tolerance was 50 mDa. Spectra were acquired by scanning a mass range of m/z 100–1000 followed by product ion scanning from m/z 30 to 1000. Collision energy was set to 35 ± 15 eV. The mass spectrometer was automatically calibrated every three injections.

Acquired data were processed with MetabolitePilot (version 1.5, SCIEX) employing different peak-finding algorithms (common product ion and neutral loss, MDF, predicted biotransformation, and generic LC peak-finding) for identifying potential metabolites. LC peak intensity threshold was set at 200 cps, MS at 50 cps, and MS/MS at 25 cps. Special attention was given to phase II metabolites that are susceptible to significant in-source fragmentation.

Analysis of Authentic Human Urine Specimens

We analyzed two urine samples collected from individuals suspected of driving under the influence of drugs, provided by the National Board of Forensic Medicine in Linköping, Sweden. These two urine specimens were not from human experimental investigations. Specimens were anonymized and de-identified prior to shipment to our laboratory for analysis. These specimens are exempt from IRB approval as they are anonymized and do not fall under human experimental investigations. The corresponding blood sample for urine case 1 contained 0.21 ng/g FUB-PB-22, and the matched blood to urine case 2 contained 1.8 ng/g FUB-PB-22 and 0.99 ng/g FDU-PB-22.

Urine samples were prepared with and without enzymatic hydrolysis as described previously (18, 22). Data acquisition and processing were the same as for hepatocyte samples; all four data mining algorithms were utilized and the search was not restricted to only metabolites previously identified in hepatocytes.

RESULTS

Metabolic Stability Evaluation in HLM

For FDU-PB-22, in vitro T1/2 was 12.4 ± 0.36 min; in vitro CLint, micr was 0.056 mL/min/mg, corresponding to an intrinsic clearance (CLint) of 52.7 mL/min/kg after scaling to whole-liver-dimensions (25). Without considering plasma protein binding and with a simplified Rowland’s equation (24, 26), we calculated the predicted human CLH as 14.5 mL/min/kg and 0.72 ER. For FUB-PB-22, the in vitro T1/2, in vitro CLint, micr, CLint, CLH, and ER were calculated to be 11.5 ± 0.03 min, 0.060 mL/min/mg, 57.1 mL/min/kg, 14.8 mL/min/kg, and 0.74, respectively.

Analysis of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 Reference Standards

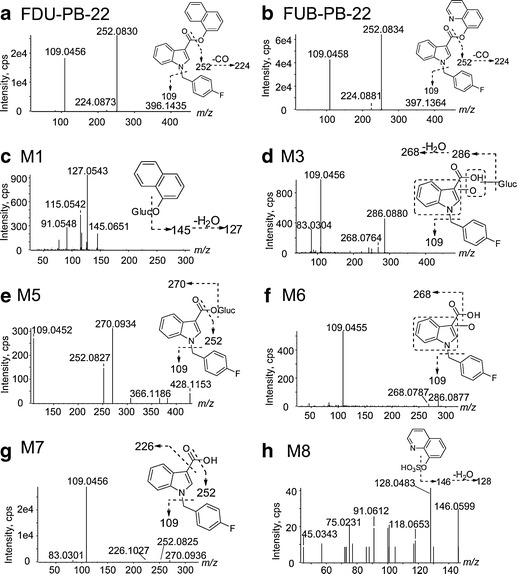

FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 chromatographic and MS fragmentation behaviors were studied first with reference standards; cleavage patterns of characteristic fragments were characterized and used to facilitate identification of their metabolites. FDU-PB-22 with [M + H]+ at m/z 396.1401 eluted at 9.74 min and showed characteristic fragment ions at m/z 252.0830, 224.0873, and 109.0456 (Figs. 2a and 3a). The base peak ion m/z 252.0830 was generated by cleavage of the ester bond; further neutral loss of CO led to m/z 224.0873; m/z 109.0456 was associated with the p-fluorobenzyl substructure. FUB-PB-22 ([M + H]+ at m/z 397.1356) eluted at 8.61 min and displayed the same fragments at m/z 252.0834, 224.0881, and 109.0458 (Figs. 2b and 3b). All fragments were used as diagnostic ions for metabolite elucidation as similar cleavage patterns could be expected.

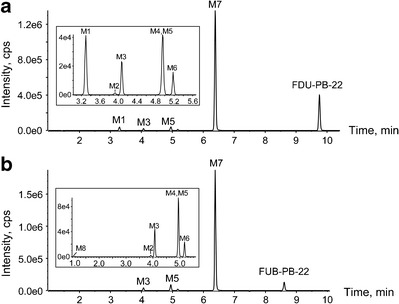

Fig. 2.

Metabolic profiles of FDU-PB-22 (a) and FUB-PB-22 (b) after 3-h incubation in human hepatocytes. The inserts are the expanded chromatograms of early eluted minor metabolites

Fig. 3.

a–h Product ion spectra, proposed structures, and fragmentation patterns of FDU-PB-22, FUB-PB-22, and their metabolites

FDU-PB-22 Metabolite Identification in Human Hepatocytes

In the 3-h hepatocyte sample, 4 phase I and 3 phase II metabolites were detected for FDU-PB-22, in addition to the parent compound (Fig. 2a, Table I). None of these metabolites were observed after incubating FDU-PB-22 in buffer for 3 h, indicating metabolites formation was enzyme-dependent. Table I lists all the metabolites with their metabolic pathway, retention time, detected m/z, mass error, formula, major fragment ions, and peak areas in the 3-h sample. Metabolites were labeled “M” in the order of retention time. An overview of the biotransformation pathway is shown in Fig. 4. Metabolite elucidation will be explained as follows.

Table I.

Identification of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 Metabolites After 3-h Incubation with Human Hepatocytes

| ID | Metabolic pathway | Time (min) | [M + H]+ (m/z) | Mass error (ppm) | Formula | Fragment ions | Area | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDU-PB-22 | FUB-PB-22 | |||||||

| FDU-PB-22 | NA | 9.74 | 396.1401 | 1.6 | C26H18NO2F | 252.0830, 224.0873, 109.0456 | 1.34E + 06 | NA |

| FUB-PB-22 | NA | 8.61 | 397.1356 | 2.3 | C25H17N2O2F | 252.0834, 224.0881, 109.0458 | NA | 4.28E + 05 |

| M1 | Naphthol + glucuronidation | 3.30 | 321.0975 | 2.1 | C16H16O7 | 145.0651, 127.0543 | 8.52E + 04a | NA |

| M2 | FBI-COOH + hydroxylation | 3.93 | 286.0878 | 1.5 | C16H12NO3F | 268.0714, 109.0448 | 3.98E + 03 | 6.44E + 03 |

| M3 | FBI-COOH + hydroxylation + glucuronidation | 4.07 | 462.1194 | −0.1 | C22H20NO9F | 286.0882, 268.0764, 109.0443 | 5.18E + 04a | 1.00E + 05a |

| M4 | FBI-COOH + hydroxylation | 4.93 | 286.0874 | 0.1 | C16H12NO3F | 109.0452 | 1.28E + 04 | 1.86E + 04 |

| M5 | FBI-COOH + glucuronidation | 4.95 | 446.1251 | 1.1 | C22H20NO8F | 270.0934, 252.0827, 109.0452 | 1.01E + 05a | 2.09E + 05a |

| M6 | FBI-COOH + hydroxylation | 5.18 | 286.0880 | 1.9 | C16H12NO3F | 268.0787, 109.0455 | 3.48E + 04 | 6.18E + 04 |

| M7 | FBI-COOH | 6.38 | 270.0932 | 2.5 | C16H12NO2F | 252.0825, 226.1027, 109.0456 | 4.00E + 06 | 5.45E + 06 |

| M8 | Quinolinol + sulfation | 1.05 | 226.0168 | −0.4 | C9H7NO4S | 146.0599, 128.0483 | NA | 4.55E + 03a |

ID identification, FBI-COOH carboxylic acid after ester hydrolysis of FDU-PB-22/FUB-PB-22, NA not applicable

aArea of corresponding aglycone due to in-source fragmentation

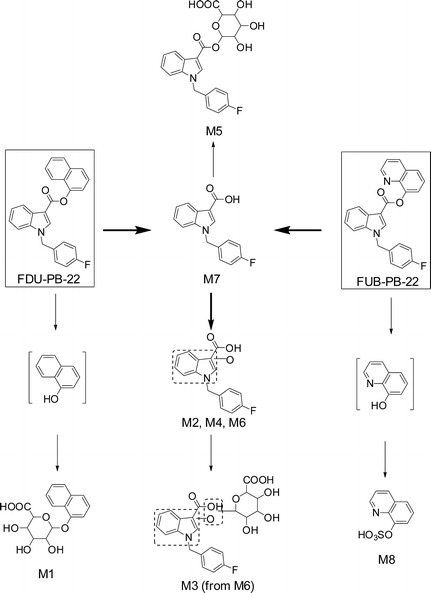

Fig. 4.

Metabolic pathways of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 in human hepatocytes

Ester Hydrolysis

FDU-PB-22 was extensively hydrolyzed via ester hydrolysis, generating M7 (FBI-COOH), and 1-naphthol, which was identified in the form of naphthol glucuronide as M1. M7 displayed a protonated molecular ion [M + H]+ at m/z 270.0932 and eluted at 6.38 min. The product ion spectrum revealed fragment ions at m/z 252.0825 and 109.0456, which were the same as those of FDU-PB-22 indicating the indole carbonyl and p-fluorobenzyl substructures were unchanged. A product ion at m/z 226.1027, which was generated by neutral loss of 43.9909 (– CO2) from the precursor ion confirmed M7 being a carboxylic acid (Fig. 3g).

M1 eluted early at 3.30 min and produced fragment ions at m/z 145.0651 and 127.0543 (Fig. 3c). Product ion m/z 145.0651 was formed by neutral loss of 176.0324 (glucuronic acid); further loss of water led to m/z 127.0543.

M7 Further Hydroxylation or Glucuronidation

The predominant metabolite M7 underwent further hydroxylation and/or glucuronidation, yielding five metabolites (M2, M3, M4, M5, and M6). Direct glucuronidation of M7 generated M5. M5 eluted at 4.95 min and produced fragment ions at m/z 270.0934, 252.0827, and 109.0452 (Fig. 3e). Product ion m/z 270.0934 was formed by neutral loss of glucuronic acid; the other two product ions were the same as M7, suggesting M5 as a glucuronide of M7.

Three hydroxylated M7 metabolites were observed, i.e., M2, M4, and M6, eluting at 3.93, 4.93, and 5.18 min, respectively. M2, M4, and M6 shared similar fragments at m/z 268.0787 and 109.0455 (Fig. 3f). Product ion m/z 268.0787 was formed by neutral loss of water from precursor ion m/z 286.0880 and was 15.9957 Da (+ O) larger than m/z 252.0830 of FDU-PB-22. Fragment m/z 109.0455 is shared with FDU-PB-22 parent, indicating the p-fluorobenzyl was unmodified. Therefore, we propose the hydroxylation to be on the indole moiety.

A glucuronide of hydroxylated M7 metabolite, M3, was detected at 4.07 min. M3 displayed product ions at m/z 286.0880, which was formed by neutral loss of glucuronic acid, and 268.0764 and 109.0456 (Fig. 3d), which are shared with M2, M4, and M6.

FUB-PB-22 Metabolite Identification in Human Hepatocytes

In total, 4 phase I and 3 phase II metabolites were detected in human hepatocytes (Fig. 2b, Table I). Table I summarizes all the metabolic pathways, observed m/z, mass error, retention time, formula, fragment ions, and peak area in the 3-h sample. An overview of the metabolic pathway is shown in Fig. 4.

Similar to FDU-PB-22, FUB-PB-22 also underwent extensive ester hydrolysis, generating M7 (FBI-COOH), and the alcohol 8-quinolinol in the form of 8-quinolinol sulfate (M8). Sequential hydroxylation or glucuronidation metabolites from M7 were also the same (Fig. 4). M8 eluted early at 1.05 min and displayed fragments at m/z 146.0599 and 128.0483 (Fig. 3h). Fragment m/z 146.0599 was formed by neutral loss of 79.9569 Da (− SO3); further loss of water led to m/z 128.0483.

Metabolite Profiling in Authentic Urine Specimens

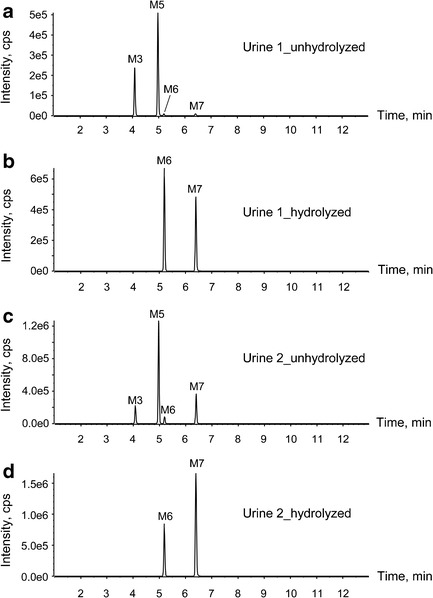

FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 were highly metabolized with no parent drug detected in human urine specimens. As shown in Fig. 5a, c, four metabolites were identified in authentic urine 1 and 2 before hydrolysis, namely, M3, M5, M6, and M7. Glucuronide conjugates M3 and M5 were predominant metabolites.

Fig. 5.

Metabolic profiles of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 in case urine 1 (a unhydrolyzed, b hydrolyzed) and case urine 2 (c unhydrolyzed, d hydrolyzed)

After hydrolysis with β-glucuronidase, M3 and M5 disappeared, and the abundance of M6 and M7 increased significantly (Fig. 5b, d). Therefore, we propose M3 as the glucuronide of M6 instead of its isomers M2 or M4 (Fig. 4); similarly, M5 was the glucuronide conjugate of M7.

DISCUSSION

HLM Metabolic Stability

In vitro T1/2 and CLint estimate a drug’s metabolic susceptibility and facilitate predicting in vivo hepatic clearance, in vivo half-life, and bioavailability (24). Short T1/2, high CLint, and predicted ER indicate that both FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 are rapidly metabolized drugs (25, 27). HLM are rich in carboxylesterases and cytochrome P450 oxidases (28); probably the liver carboxylesterases catalyzed the hydrolysis of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22.

Metabolism of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 Compared to 5F-PB-22 and AB-FUBINACA

FDU-PB-22, FUB-PB-22, and 5F-PB-22 share similar substructures, i.e., an indole connects with naphthalene or quinoline via an ester bond. As expected, 5F-PB-22, FDU-PB-22, and FUB-PB-22 degraded significantly after 3-h incubation in hepatocytes. Ideally, intense metabolites that are specific for each parent compound should be targeted in forensic drug testing. In our study, however, no specific marker for FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 could be identified as both molecules are hydrolyzed quickly losing an essential part of their original structure. Though not perfect, FBI-COOH and its subsequent metabolites are considered the best targets based on our results.

Oxidative defluorination was the major metabolic pathway for ω-fluoropentyl chain containing drugs, such as 5F-PB-22, 5F-AKB-48, and THJ-2201 (8, 29, 30). In our study, the p-fluorobenzyl moiety was metabolically stable in the hepatocyte incubation and in vivo, with no biotransformation identified. This is consistent with metabolism of AB-FUBINACA, where aromatic defluorination and aromatic hydroxylation did not occur (19).

FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 Shared Metabolites

Ester hydrolysis was the primary biotransformation for both compounds. In hepatocyte samples and authentic urine specimens, no FDU-PB-22 or FUB-PB-22 metabolites were detected that did not include ester hydrolysis. After ester hydrolysis, both compounds shared the same carboxylic acid metabolite, FBI-COOH (M7). FDU-PB-22, and FUB-PB-22 generated their specific alcohol conjugated metabolites M1 (naphthol glucuronide) versus M8 (quinolinol sulfate). Naphthol sulfate and quinolinol glucuronide were specifically investigated, but were not observed. However, the structures of M1 and M8 are too common and simple to be representative markers of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 as they can also derive from other drugs of abuse, medicine, or food supplements (31).

Urinary Metabolites for Documenting FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 Intake

Urine is the most common matrix for drug detection and screening due to easy collection, adequate specimen volume, and higher drug concentrations compared to blood producing prolonged detection windows, hence, the importance of identifying urinary metabolites. When extrapolating the hepatocyte metabolites to human urine, some issues such as extrahepatic metabolism (32), kidney uptake or efflux transporters (33), metabolites’ enrichment in urine (34, 35), and time after drug intake may affect the relative abundance of urinary metabolites and selection of confirming markers. Thus, it is important to evaluate the metabolic profiles in authentic urine specimens if available to further document FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 urinary markers.

In our study, we analyzed two urine specimens collected from individuals suspected of driving under the influence of drugs. The corresponding blood of urine 1 was positive for FUB-PB-22, and the corresponding blood of urine 2 was positive for FUB-PB-22 and FDU-PB-22. For both urine samples, two primary metabolites were detected after hydrolysis, namely, M6 (hydroxylated FBI-COOH) and M7 (FBI-COOH). Similar to the metabolic profile in the hepatocyte samples, M7 also was the predominant metabolite in both urine specimens. The relative abundance of M6 in urine was much higher than in hepatocytes most likely due to urine specimen collection times later after FDU-PB-22 and/or FUB-PB-22 ingestion than the 3-h hepatocyte incubation time. The abundance ratio of M6 to M7 in urine 1 is different from that in urine 2; this may be attributed by various factors, such as different collection time points and individual variability in drug-metabolizing enzyme activities (19, 22, 36).

Definitively identifying the substance consumed is required for forensic testing in some jurisdictions and is difficult when identical metabolites arise from both a scheduled and non-scheduled compound. Therefore, metabolites M6 (hydroxylated FBI-COOH) and M7 (FBI-COOH) are good urinary markers to confirm consumption of FDU-PB-22 and/or FUB-PB-22. However, it is not possible to distinguish FDU-PB-22 from FUB-PB-22 intake, because after extensive ester hydrolysis, they share the same metabolites (M2–M7, Fig. 4). As discussed, M1 and M8 can derive from many origins and their structures are too simple to be representative of FDU-PB-22 or FUB-PB-22. Although the corresponding blood of urine 1 was only positive for FUB-PB-22 and the corresponding blood of urine 2 was positive for both FUB-PB-22 and FDU-PB-22, they had similar metabolite profiles. Definitive differentiation of FDU-PB-22 from FUB-PB-22 intake would require identification of the parent compound in the blood or oral fluid, and the windows of detection of the potent parent compounds in these matrices are expected to be short based on their metabolic stability and low dosage.

Usefulness of Hepatocyte Incubation Model for In Vivo Human Metabolite Confirmation

Human hepatocytes offer many advantages over HLM for identifying human metabolites of NPS. Hepatocytes are more representative of the physiological liver environment containing all phase I and II drug-metabolizing enzymes, cofactors (such as NADPH), and drug transporters (21, 37–39). In addition, compounds must penetrate across cell membranes before being metabolized, which is not the case for HLM. The hepatocyte incubation model has proven to be successful in confirming consumption of AB-FUBINACA (19), AB-PINACA (22), and AH-7921 (23). In our study, the top 2 major metabolites in hepatocytes, M6 (hydroxylated FBI-COOH) and M7 (FBI-COOH), are also the dominant metabolites in authentic urine specimens.

These data empower clinical laboratories to target urinary markers of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 intake and manufacturers to focus their synthesis efforts on the most appropriate target M7. These data also enable linkage of adverse events to specific SC or in this case to either FDU-PB-22 or FUB-PB-22. Our analytical hepatocyte incubation and HR-MS strategy is applicable for studies of newly emerging SC.

CONCLUSIONS

We characterized for the first time, in vitro and in vivo human metabolism of FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22. The hepatocyte incubation model has proven to be successful in predicting in vivo human major metabolites. In authentic urine specimens, M6 (hydroxylated FBI-COOH) and M7 (FBI-COOH) were primary metabolites and are proposed as the best urinary markers for documenting FDU-PB-22 and/or FUB-PB-22 intake. These data establish the foundation for forensic and clinical scientists to develop analytical screening methods for identifying FDU-PB-22 and/or FUB-PB-22 intake.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health. FDU-PB-22 and FUB-PB-22 were generously donated by the US Drug Enforcement Administration. Molecular Discovery kindly provided the MetaSite software.

Abbreviations

- CLH

Hepatic clearance

- CLint, micr

Microsomal intrinsic clearance

- ER

Extraction ratio

- ESI

Electrospray ionization

- FDU-PB-22

Naphthalen-1-yl 1-[(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]-1H-indole-3-carboxylate

- FUB-PB-22

Quinolin-8-yl 1-[(4-fluorophenyl)methyl]-1H-indole-3-carboxylate

- HLM

Human liver microsomes

- HPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography

- HR-MS

High-resolution mass spectrometry

- FBI-COOH

Fluorobenzylindole-3-carboxylic acid

- IDA

Information-dependent acquisition

- MDF

Mass defect filter

- NPS

Novel psychoactive substance

- Q

Qualifier ion

- SC

Synthetic cannabinoid

- T

Target ion

- T1/2

Half-life

- TOF

Time of flight

References

- 1.Pertwee RG. Cannabinoid pharmacology: the first 66 years. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(Suppl 1):S163–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huffman JW, Dai D, Martin BR, Compton DR. Design, synthesis and pharmacology of cannabimimetic indoles. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1994;4(4):563–6. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(01)80155-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wohlfarth A, Pang S, Zhu M, Gandhi AS, Scheidweiler KB, Liu HF, et al. First metabolic profile of XLR-11, a novel synthetic cannabinoid, obtained by using human hepatocytes and high-resolution mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2013;59(11):1638–48. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.209965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermanns-Clausen M, Kneisel S, Szabo B, Auwarter V. Acute toxicity due to the confirmed consumption of synthetic cannabinoids: clinical and laboratory findings. Addiction. 2013;108(3):534–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seely KA, Lapoint J, Moran JH, Fattore L. Spice drugs are more than harmless herbal blends: a review of the pharmacology and toxicology of synthetic cannabinoids. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39(2):234–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forrester MB, Kleinschmidt K, Schwarz E, Young A. Synthetic cannabinoid and marijuana exposures reported to poison centers. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2012;31(10):1006–11. doi: 10.1177/0960327111421945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young AC, Schwarz E, Medina G, Obafemi A, Feng SY, Kane C, et al. Cardiotoxicity associated with the synthetic cannabinoid, K9, with laboratory confirmation. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(7):1320 e5–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wohlfarth A, Gandhi AS, Pang S, Zhu M, Scheidweiler KB, Huestis MA. Metabolism of synthetic cannabinoids PB-22 and its 5-fluoro analog, 5F-PB-22, by human hepatocyte incubation and high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;406(6):1763–80. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-7668-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uchiyama N, Asakawa K, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Tsutsumi T, Hakamatsuka T. A new pyrazole-carboxamide type synthetic cannabinoid AB-CHFUPYCA [N-(1-amino-3-methyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)-1-(cyclohexylmethyl)-3-(4-fluorophenyl)-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxamide] identified in illegal products. Forensic Toxicol. 2015;33(2):367–73. doi: 10.1007/s11419-015-0283-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. New psychoactive substances in Europe. 2015 [cited 2015 April 12]; Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_235958_EN_TD0415135ENN.pdf.

- 11.Uchiyama N, Shimokawa Y, Kawamura M, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Hakamatsuka T. Chemical analysis of a benzofuran derivative, 2-(2-ethylaminopropyl)benzofuran (2-EAPB), eight synthetic cannabinoids, five cathinone derivatives, and five other designer drugs newly detected in illegal products. Forensic Toxicol. 2014;32(2):266–81. doi: 10.1007/s11419-014-0238-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchiyama N, Shimokawa Y, Kikura-Hanajiri R, Demizu Y, Goda Y, Hakamatsuka T. A synthetic cannabinoid FDU-NNEI, two 2H-indazole isomers of synthetic cannabinoids AB-CHMINACA and NNEI indazole analog (MN-18), a phenethylamine derivative N-OH-EDMA, and a cathinone derivative dimethoxy-alpha-PHP, newly identified in illegal products. Forensic Toxicol. 2015;33(2):244–59. doi: 10.1007/s11419-015-0268-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shevyrin V, Melkozerov V, Nevero A, Eltsov O, Baranovsky A, Shafran Y. Synthetic cannabinoids as designer drugs: new representatives of indol-3-carboxylates series and indazole-3-carboxylates as novel group of cannabinoids. Identification and analytical data. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;244:263–75. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roussel O, Cralin MG, Bouvot X, Tensorer L. The emergence of synthetic cannabinoids in Mayotte. Toxicol Anal Clin. 2015;27:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drugs-Forum. [cited 2015 May 18]; Available from: https://drugs-forum.com/forum/showthread.php?t=231374.

- 16.Chimalakonda KC, Seely KA, Bratton SM, Brents LK, Moran CL, Endres GW, et al. Cytochrome P450-mediated oxidative metabolism of abused synthetic cannabinoids found in K2/Spice: identification of novel cannabinoid receptor ligands. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40(11):2174–84. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.047530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobolevsky T, Prasolov I, Rodchenkov G. Detection of urinary metabolites of AM-2201 and UR-144, two novel synthetic cannabinoids. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4(10):745–53. doi: 10.1002/dta.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheidweiler KB, Jarvis MJ, Huestis MA. Nontargeted SWATH acquisition for identifying 47 synthetic cannabinoid metabolites in human urine by liquid chromatography-high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2015;407(3):883–97. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-8118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castaneto MS, Wohlfarth A, Pang SK, Zhu MS, Scheidweiler KB, Kronstrand R, et al. Identification of AB-FUBINACA metabolites in human hepatocytes and urine using high-resolution mass spectrometry. Forensic Toxicol. 2015;33(2):295–310. doi: 10.1007/s11419-015-0275-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diao X, Pang X, Xie C, Guo Z, Zhong D, Chen X. Bioactivation of 3-n-butylphthalide via sulfation of its major metabolite 3-hydroxy-NBP: mediated mainly by sulfotransferase 1A1. Drug Metab Dispos. 2014;42(4):774–81. doi: 10.1124/dmd.113.056218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soars MG, McGinnity DF, Grime K, Riley RJ. The pivotal role of hepatocytes in drug discovery. Chem Biol Interact. 2007;168(1):2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wohlfarth A, Castaneto MS, Zhu M, Pang S, Scheidweiler KB, Kronstrand R, et al. Pentylindole/pentylindazole synthetic cannabinoids and their 5-fluoro analogs produce different primary metabolites: metabolite profiling for AB-PINACA and 5F-AB-PINACA. AAPS J. 2015;17(3):660–77. doi: 10.1208/s12248-015-9721-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wohlfarth A, Scheidweiler KB, Pang S, Zhu M, Castaneto M, Kronstrand R, et al. Metabolic characterization of AH-7921, a synthetic opioid designer drug: in vitro metabolic stability assessment and metabolite identification, evaluation of in silico prediction, and in vivo confirmation. Drug Test Anal. 2015 doi: 10.1002/dta.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baranczewski P, Stanczak A, Sundberg K, Svensson R, Wallin A, Jansson J, et al. Introduction to in vitro estimation of metabolic stability and drug interactions of new chemical entities in drug discovery and development. Pharmacol Rep. 2006;58(4):453–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNaney CA, Drexler DM, Hnatyshyn SY, Zvyaga TA, Knipe JO, Belcastro JV, et al. An automated liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry process to determine metabolic stability half-life and intrinsic clearance of drug candidates by substrate depletion. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2008;6(1):121–9. doi: 10.1089/adt.2007.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diao XX, Zhong K, Li XL, Zhong DF, Chen XY. Isomer-selective distribution of 3-n-butylphthalide (NBP) hydroxylated metabolites, 3-hydroxy-NBP and 10-hydroxy-NBP, across the rat blood-brain barrier. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36(12):1520–7. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lave T, Dupin S, Schmitt C, Valles B, Ubeaud G, Chou RC, et al. The use of human hepatocytes to select compounds based on their expected hepatic extraction ratios in humans. Pharm Res. 1997;14(2):152–5. doi: 10.1023/A:1012036324237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomsen R, Nielsen LM, Holm NB, Rasmussen HB, Linnet K. Synthetic cannabimimetic agents metabolized by carboxylesterases. Drug Test Anal. 2015;7(7):565–76. doi: 10.1002/dta.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holm NB, Pedersen AJ, Dalsgaard PW, Linnet K. Metabolites of 5F-AKB-48, a synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonist, identified in human urine and liver microsomal preparations using liquid chromatography high-resolution mass spectrometry. Drug Test Anal. 2015;7(3):199–206. doi: 10.1002/dta.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diao X, Wohlfarth A, Pang S, Scheidweiler KB, Huestis MA. High-resolution mass spectrometry for characterizing the metabolism of synthetic cannabinoid THJ-018 and its 5-fluoro analog THJ-2201 after incubation in human hepatocytes. Clin Chem. 2016;62(1):157–69. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.243535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michael JP. Quinoline, quinazoline and acridone alkaloids. Nat Prod Rep. 1999;16(6):697–709. doi: 10.1039/a809408j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li XD, Xia SQ, Lv Y, He P, Han J, Wu MC. Conjugation metabolism of acetaminophen and bilirubin in extrahepatic tissues of rats. Life Sci. 2004;74(10):1307–15. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao C, Zhang H, Guo Z, You T, Chen X, Zhong D. Mechanistic studies on the absorption and disposition of scutellarin in humans: selective OATP2B1-mediated hepatic uptake is a likely key determinant for its unique pharmacokinetic characteristics. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40(10):2009–20. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.047183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie C, Zhou J, Guo Z, Diao X, Gao Z, Zhong D, et al. Metabolism and bioactivation of famitinib, a novel inhibitor of receptor tyrosine kinase, in cancer patients. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168(7):1687–706. doi: 10.1111/bph.12047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao R, Li L, Xie C, Diao X, Zhong D, Chen X. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of morinidazole in humans: identification of diastereoisomeric morpholine N+-glucuronides catalyzed by UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1A9. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40(3):556–67. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.042689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitamura T, Suzuki M, Nishimatsu H, Kurosaki T, Enomoto Y, Fukuhara H, et al. Final report on low-dose estramustine phosphate (EMP) monotherapy and very low-dose EMP therapy combined with LH-RH agonist for previously untreated advanced prostate cancer. Aktuelle Urol. 2010;41(Suppl 1):S34–40. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1224657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li AP, Gorycki PD, Hengstler JG, Kedderis GL, Koebe HG, Rahmani R, et al. Present status of the application of cryopreserved hepatocytes in the evaluation of xenobiotics: consensus of an international expert panel. Chem Biol Interact. 1999;121(1):117–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Ellefsen K, Wohlfarth A, Swortwood M, Diao X, Concheiro M, Huestis M. 4-Methoxy-α-PVP: in silico prediction, metabolic stability, and metabolite identification by human hepatocyte incubation and high-resolution mass spectrometry. Forensic Toxicol. 2016;34(1):61–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Swortwood MJ, Carlier J, Ellefsen KN, Wohlfarth A, Diao X, Concheiro-Guisan M, et al. In vitro, in vivo and in silico metabolic profiling of α-pyrrolidinopentiothiophenone, a novel thiophene stimulant. Bioanalysis. 2016;8(1):65–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]