Abstract

Progesterone-based injectable hormonal contraceptives (HCs) potentially modulate genital barrier integrity and regulate the innate immune environment in the female genital tract, thereby enhancing risk for STIs or HIV infection. We investigated the effects of injectable HC use on concentrations of inflammatory cytokines and other soluble factors associated with genital epithelial repair and integrity. The concentrations of 42 inflammatory, regulatory, adaptive, growth factors and hematopoetic cytokines, five matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and four tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) were measured in cervicovaginal lavages (CVLs) from 64 HIV negative women using injectable HCs and 64 control women not using any HCs, in a matched case-control study. There were no differences between groups in the prevalence of bacterial vaginosis (BV; nugent score ≥7), or common sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In multivariate analyses adjusting for condom use, sex work status, marital status, BV and STIs, median concentrations of chemokines (eotaxin, MCP-1, MDC), adaptive cytokines (IL-15), growth factors (PDGF-AA) and a metalloproteinase (TIMP-2) were significantly lower in CVLs from women using injectable HCs than controls. In addition, pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-12p40 and chemokine fractalkine were less likely to have detectable levels in women using injectable HCs compared to those not using HCs. We conclude that injectable HC use was associated with an immunosuppressive female genital tract innate immune profile. While the relationship between injectable HC use and STI or HIV risk is yet to be resolved, our data suggest that injectable HCs effects were similar between STI positive and STI negative participants.

Keywords: hormonal contraceptives, DMPA, Net-EN, cytokines, MMP, TIMP

1.0 Introduction

Internationally, hormonal contraceptives (HCs) are widely used by women to prevent unplanned pregnancies. In South Africa, more than half of women aged 15–49 years old use depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) or norethisterone enanthate (Net-EN), with more than 3 times the number of women using DMPA than Net-EN (Sibeko et al., 2011). DMPA is an aqueous microcrystalline suspension (150mg/ml) administered by intramuscular depot injection every three months while NET-EN injection contains 200mg/ml of norethisterone that is effective for two months as a contraception ((Bhathena, 2001, Elder, 1984, Fraser and Weisberg, 1981). DMPA primarily provides contraceptive protection by suppressing natural cyclic fluctuations of female sex hormones resulting in a hypoestrogenic state (Jeppsson et al., 1982). In addition, DMPA induces atrophy of the endometrium by decreasing glycogen content needed to provide energy for the development of the blastocyst after the morula has entered the uterine cavity (Hatcher et al., 2011, Mishell et al., 1968). Less is known about then endogenous effects of Net-EN.

High-dose DMPA use is common in the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) vaginal challenge models because it results in thinning of the vaginal epithelium, which enhances genital SIV infection (Abel et al., 2004, Trunova et al., 2006, Wieser et al., 2001, Marx et al., 1996). The role of DMPA in increasing risk of HIV infection is contentious. While some studies have reported such risks (Hel et al., 2010, Morrison et al., 2010, Ungchusak et al., 1996, Baeten et al., 2007, Heffron et al., 2012, Kumwenda et al., 2008), others have found no association (Kiddugavu et al., 2003, Kleinschmidt et al., 2007, Myer et al., 2007, Reid et al., 2010, Stringer et al., 2009). The impact of DMPA on genital epitheial barrier intergrity is similary contentius (Kiddugavu et al., 2003, Myer et al., 2007).

In addition to potentially increasing HIV acquisition risk, DMPA has been associated with an increased risk of Chlamydia trachomatis infection and at decreased risk of aquiring other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as Trichomonas vaginalis and bacterial vaginosis (BV) (Baeten et al., 2001, van de Wijgert et al., 2013).

It has been hypothesised that DMPA might increase HIV aquisition risks by changing the inflammatory or chemotactic environment of the genital mucosa so as to increase the recruitment of HIV susceptible immune cells to the mucosa (Ildgruben et al., 2003, Miller et al., 2000, Wieser et al., 2001, Wira et al., 2011, Wira and Veronese, 2011). However, treatment of PBMC with DMPA has been shown to causes reduced production of several inflammatory and adaptive cytokines (Huijbregts et al., 2013). At the female genital mucosa, suppression of innate immune responses may influence susceptibility to infections. Moreover, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are required during normal reproductive processes (such as menstruation) for extracellular matrix degradation and tissue remodeling in the endometrial compartment of the upper genital tract (Lockwood and Schatz, 1996, Rodgers et al., 1994, Rodgers et al., 1993, Birkedal-Hansen, 1995, Cawston, 1995), may influence epithelial barrier repair in the lower genital tract. MMPs are regulated by specific tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) (Fernandez-Catalan et al., 1998, Gomis-Ruth et al., 1997), which may similarly be involved in maintainence of the lower reproductive tract barrier.

Defining the impact of injectable HCs on female genital tract innate immunity in relation to susceptibility to STIs or BV, will provide important insights into biological co-factors influencing HIV risk in women. The aim of this study was to compare concentrations of genital tract soluble immune mediators (including cytokines, MMPs and TIMPs) between women using long-acting injectable HCs and women not using HCs, while accounting for BV and common STIs.

2.0 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design, participants and sample collection

Our study included 64 HIV-uninfected women using injectable HCs (DMPA or Net-EN) and 64 women not using HCs, enrolled into the prospective CAPRISA 002 observational cohort study of acute HIV infection conducted at the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA), in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, as previously described (Mlisana et al., 2012, van Loggerenberg et al., 2012). Non-HC users were matched to injectable HC users based on age (within 5 years of age) at a 1:1 ratio. Demographic and clinical data were collected at enrolment using a structured questionnaire administered by a trained counsellor. Although data on type of contraception (injectable HCs, combined oral contraceptives (COCs), intrauterine devices (IUDs), condoms, diaphrams, foam and jelly, or were sterilised) was collected no information was collected on whether the injectable contraceptive being used was DMPA or Net-EN. We therefore report on injectable HCs in this study as a combination of DMPA and Net-EN users. Women using COC or any other form of hormal contraception were excluded from the study, with an exception of IUD user. Laboratory samples, including cervicovaginal lavages (CVLs) were collected from each participant at enrolment by gently flushing the cervix and the lateral vaginal walls with 10ml sterile normal saline, as previously described by Mlisana et al. (2012). Volume of saline recovered after the lavage were not typically recorded. CVLs were transported within 4 hours on ice from the site to the laboratory. In the laboratory, CVLs were centrifuged, the supernatant collected and stored at −80°C. The protocol for this study was approved by the Ethical Review Committees of the University of KwaZulu-Natal and University of Cape Town.

2.2 Testing for STIs and BV

At enrollment, vulvovaginal swabs collected from the posterior fornices and lateral vaginal walls from each woman were tested for C. trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Mycoplasma genitalium, HSV-2 reactivation and T. vaginalis using PCR. Gram stain was performed to diagnose BV using Nugent score ≥7 (Mlisana et al., 2012).

2.3 Cytokine, MMP and TIMP measurements in CVL

Concentrations of cytokines, MMPs and TIMPS were measured in CVLs collected at enrollment,. We measured 42 cytokines [including IL-1α, IL-3, IL-9, IL-12p40, IL-15, IL-17, epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-AA, transforming growth factor (TGF)-α, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), eotaxin/CCL11, FGF-2, FLT3 Ligand (FLT3L), fractalkine/CX3CL1, G-CSF, growth related oncogene (GRO) family (CXCL1-CXCL3), IFN-α, IFN-γ-induced protein (IP)-10/CXCL10, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1/CCL2, MCP-3/CCL7, macrophage-derived chemokine (MDC)/CCL22, MIP-1α/CCL3, MIP-1β/CCL4, PDGF-AB/BB, RANTES/CCL5, soluble CD40 ligand (sCD40L), soluble IL-2 receptor α (sIL-2Rα), TNF-β, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8 (CXCL8), IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, GM-CSF, IFN-γ and TNF-α]; 4 TIMPs [TIMP-1, -2, -3, -4]; and 5 MMPs [MMP-1, -2, -7, -9 and -10]. The Human Cytokine and High Sensitivity LINCOplex Premixed kits (LINCO Research, MO, U.S.A.) were used to measure cytokines; and the TIMP Panel 2 and MMP Panel-2 kits were used to measure TIMPs and MMPs, respectively (Merck-Millipore, Missouri, U.S.A.). CVLs were thawed overnight on ice and filtered by centrifugation using 0.2 μm cellulose acetate filters (Sigma, U.S.A.). All markers were measured in undiluted CVL, except for MMP-9 (which was measured at 50-fold dilution), on a Bio-Plex 100 system (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc®, Hercules, California). Bio-Plex manager software (version 5.0; Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc®) was used to analyse the data and all analyte concentrations were extrapolated from the standard curves using a 5 parameter logistic (PL) regression equation. Analyte concentrations that were below the lower limit of detection of the assay were reported as the mid-point between zero and the lowest concentration measured for each analyte. For IL-8, only two samples had readings above the upper limit of detection. For these two samples, IL-8 concentrations were reported as halfway between the highest concentration and the upper limit of the standard curve.

2.4 Statistical analyses

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare proportions, while a t-test was used to compare ages between groups. To assess the effect of injectable HCs on cytokine levels, linear regression analysis was used. Cytokines that were undetectable in at least a third of women (IL-2, IL-2Rα, IL-3, IL-4, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, IL-13, Fractalkine, MIP-1α, IFN-α, EGF, TFG-α, FGF-2, PDGF-AB/BB and MMP-2) were dichotomised (i.e. being rated as either present or absent in each woman) and logistic regression was used to estimate the effect of injectable HCs on the detectability of these cytokines. Linear and logistic regression analyses were adjusted for sex worker status, age, condom use at last sex act, BV and STIs. In addition, interaction terms were tested to assess whether injectable HCs modified the effect of STIs on cytokine concentrations. Because of the small number of women testing positive for cervical STIs, C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae or M. genitalium, these STIs were grouped together [Gonorrhea-Chlamydia-Mycoplasma (GCM)] for the purposes of this analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary).

3.0 Results

This study included a total of 128 women, 64 of whom were non-HC users (including 1 woman using an IUD) and 64 of whom were injectable HC users (either DMPA or Net-EN) (Table 1). Of these 128 women, 79.7% were self-reported sex workers and this did not differ between groups. Women using injectable HCs were less likely to be single than those not using injectable HCs (0.0% compared to 4.7%; p=0.057), and less likely to report having multiple partners (52.4% versus 65.6%), although this was not significant. Condom use at last sex act was similar among women using injectable HC and of women not using HCs (53.1% vs 65.6%, p=0.208).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

| Variables | Overall | Injectable-HCs users | Non-HCs users | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 128 | 64 | 64 | |

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 28 (23–36) | 28 (23–36) | 29 (23–37) | 0.653 |

| Marital status [% (n)] | ||||

| Single | 2.4% (3) | 0.0% (0) | 4.7% (3) | 0.057 |

| Stable partner | 34.7% (44) | 41.3% (26) | 28.1% (18) | |

| Married | 3.9% (5) | 6.4% (4) | 1.6% (1) | |

| Many partners | 59.1% (75) | 52.4% (33) | 65.6% (42) | |

| Sex work [% (n)] | 79.7% (102) | 79.7% (51) | 79.7% (51) | 1.000 |

| Education [% (n)] | ||||

| <Grade 8 | 21.9% (28) | 21.9% (14) | 21.9% (14) | 0.972 |

| Grade 8–10 | 29.7% (38) | 28.1% (18) | 31.3% (20) | |

| Grade 11–12 | 48.4% (62) | 50.0% (32) | 46.9% (30) | |

| Condom use [% (n)] | ||||

| Always use condom with steady partner(s) | 25.0% (32) | 20.3% (13) | 29.7% (19) | 0.308 |

| Always use condom with casual partner(s) | 53.9% (69) | 46.9% (30) | 60.9% (39) | 0.156 |

| Condom use at last sex act | 59.4% (76) | 53.1% (34) | 65.6% (42) | 0.208 |

| Positive test or culture result [% (n)] | ||||

| Genital discharge | 17.2% (22) | 12.5% (8) | 21.9% (14) | 0.241 |

| Bacterial vaginosis (Nugent >7) | 51.2% (65) | 50.8% (32) | 51.6% (33) | 1.000 |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | 18.9% (24) | 19.1% (12) | 18.8% (12) | 1.000 |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | 6.3% (8) | 4.8% (3) | 7.8% (5) | 0.718 |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | 6.3% (8) | 1.6% (1) | 10.9% (7) | 0.062 |

| Mycoplasma genitalium | 1.6% (2) | 3.2% (2) | 0.0% (0) | 0.244 |

| HSV-2 PCR | 2.4% (3) | 3.2% (2) | 1.6% (1) | 1.000 |

Descriptive statistics are reported as percentages (categorical data) or medians and IQRs (continuous data).

3.1 Prevalence of BV and STIs in injectable HC versus non-HC users

To investigate the association between injectable HC use and STIs, the prevalence of C. trachomatis, T. vaginalis and BV in women using injectable HCs was compared to those who were not using HCs. At baseline (Table 1), more than half of the women in this cohort had BV (nugent score ≥7), and this did not differ significantly between women not using HCs and those using injectable HCs (51.6% and 50.8%, respectively; p=1.000). Nineteen percent of women were infected with T. vaginalis and this was similar between groups (19.1% for injectable HC users and 18.8% for non-HC users; p=1.000). The prevalence of C. trachomatis (6.3%), N. gonorrhoeae (6.3%), M. genitalium (1.6%), and HSV-2 (2.4%) were relatively low in this cohort and were also similar between groups (Table 1).

3.2 Impact of injectable HCs on innate immune factors in the female genital tract

To better understand how injectable HC use influenced the genital tract innate environment, the concentrations of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and markers of tissue repair or remodelling (MMPs and TIMPs) were compared in CVL from women using injectable HCs and those not using HCs (Table 2). Of the 42 chemokines, growth factors and inflammatory cytokines that were measured, 5/42 (11.9%) had significantly decreased median concentrations in the CVL of women using injectable HCs than those not using HCs, after adjusting for age, condom use, sex worker status, marital status, STIs, and BV. This included several chemokines, including eotaxin [beta-coefficient (β)=−0.334, p=0.004], MCP-1 (β=−0.359, p=0.015), MDC (β=−0.364, p=0.003); the growth factor PDGF-AA (β=−0.506, p=0.001); the adaptive cytokine IL-15 (β=−0.240, p=0.038). In addition, pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-12p40 (β=−1.059, p=0.009) and chemokine fractalkine (β=−0.910, p=0.028) were less likely to be detectable in women using injectable HCs compared to those not using HCs. While linear regression was used to estimate the effect of injectable HCs on concentrations of eotaxin, MCP-1, and MDC, a logistic regression model was fitted to estimate the effect of injectable HC use on the detectability of fractalkine and IL-12p40 because the concentrations of these cytokines were undetectable in at least a third of the women in this study. Furthermore, the median concentration of TIMP-2 was significantly lower in women using injectable HCs than those not using HCs (β=−0.207, p=0.027). In contrast, no differences were observed in MMP concentrations. None of the cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and markers of tissue repair concentrations were significantly different between groups.

Table 2.

Influence of injectable hormonal contraceptive use on cytokine, MMP and TIMP concentrations in genital secretions

| Functional groups | Cytokine | Injectable HC users (n=64) | Non-HC users (n=64) | Multivariate# | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Median (pg/ml) | IQR | Median (pg/ml) | IQR | Beta coefficient (SE) | P value | ||

| Pro-inflammatory | TNF-β | 7.60 | 3.36 – 19.05 | 11.53 | 5.31 – 21.83 | −0.197 (0.104) | 0.061 |

| IL-12p40† | 0.12 | 0.12 – 14.39 | 12.20 | 0.12 – 38.24 | −1.059 (0.404) | 0.009 | |

| IL-12p70† | 0.02 | 0.01 – 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 – 0.09 | 0.363 (0.414) | 0.381 | |

| IL1α | 38.02 | 14.26 – 172.71 | 87.37 | 30.40 – 259.69 | −0.128 (0.126) | 0.311 | |

| IL-6 | 2.57 | 0.84 – 11.79 | 2.56 | 0.36 – 16.41 | 0.140 (0.198) | 0.481 | |

| TNF-α | 0.04 | 0.03 – 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.02 – 0.05 | 0.223 (0.114) | 0.053 | |

| IL-1β | 0.79 | 0.14 – 5.96 | 0.76 | 0.19 – 5.81 | −0.005 (0.169) | 0.979 | |

|

| |||||||

| Chemokine | Eotaxin | 0.31 | 0.26 – 3.09 | 2.32 | 0.31 – 5.27 | −0.334 (0.114) | 0.004 |

| MCP-1 | 6.33 | 2.80 – 19.39 | 13.97 | 4.85 – 72.18 | −0.359 (0.146) | 0.015 | |

| MDC | 10.97 | 4.60 – 33.28 | 35.52 | 12.15 – 63.15 | −0.364 (0.119) | 0.003 | |

| Fractalkine† | 2.13 | 2.13 – 23.60 | 18.01 | 2.13 – 40.10 | −0.910 (0.414) | 0.028 | |

| MIP1α† | 0.66 | 0.66 – 5.73 | 0.66 | 0.66 – 19.83 | −0.422 (0.472) | 0.370 | |

| MCP-3 | 9.35 | 1.95 – 12.41 | 12.34 | 8.47 – 15.42 | −0.106 (0.063) | 0.097 | |

| IP-10 | 22.95 | 3.78 – 88.25 | 45.96 | 13.30 – 182.40 | −0.393 (0.211) | 0.066 | |

| GRO | 370.82 | 134.00 – 1263.72 | 598.60 | 236.09 – 1974.89 | −0.178 (0.128) | 0.167 | |

| MIP-1β | 3.18 | 0.26 – 5.27 | 4.31 | 0.70 – 7.93 | −0.028 (0.252) | 0.911 | |

| IL-8 | 157.89 | 69.74 – 510.09 | 131.05 | 54.80 – 1029.17 | 0.112 (0.129) | 0.389 | |

| RANTES | 3.65 | 2.24 – 9.62 | 3.21 | 0.93 – 9.98 | 0.202 (0.136) | 0.138 | |

|

| |||||||

| Innate | IFNα† | 0.68 | 0.68 – 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.68 – 8.91 | −0.874 (0.446) | 0.050 |

|

| |||||||

| Hematopoietic | IL-9 | 0.68 | 0.01 – 1.24 | 1.19 | 0.23 – 1.76 | −0.319 (0.188) | 0.093 |

| Flt3L | 4.27 | 0.45 – 9.48 | 6.56 | 2.94 – 10.56 | −0.174 (0.110) | 0.116 | |

| G-CSF | 17.17 | 2.76 – 73.44 | 26.80 | 4.71 – 117.07 | −0.256 (0.208) | 0.222 | |

| GM-CSF | 0.14 | 0.02 – 0.38 | 0.13 | 0.01 – 0.47 | 0.077 (0.141) | 0.588 | |

| IL-7 | 0.25 | 0.08 – 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.02 – 0.61 | −0.033 (0.123) | 0.791 | |

| IL-3 | 3.08 | 0.01 – 14.86 | 8.35 | 0.01 – 28.18 | −0.229 (0.415) | 0.580 | |

|

| |||||||

| Growth Factor | PDGF-AA | 4.55 | 2.54 – 19.81 | 15.77 | 5.85 – 118.91 | −0.506 (0.146) | 0.001 |

| TGF-α | 2.35 | 0.99 – 4.19 | 3.37 | 2.14 – 5.79 | −0.173 (0.101) | 0.089 | |

| VEGF | 73.86 | 17.27 – 151.91 | 77.09 | 12.95 – 120.64 | −0.033 (0.100) | 0.742 | |

| PDGF-AB/BB† | 0.09 | 0.09 – 17.43 | 0.09 | 0.09 – 38.66 | −0.185 (0.417) | 0.658 | |

| EGF† | 0.56 | 0.56 – 2.30 | 0.56 | 0.56 – 8.61 | −0.632 (0.427) | 0.139 | |

| FGF-2† | 0.30 | 0.30 – 8.39 | 5.32 | 0.30 – 13.15 | −0.539 (0.394) | 0.171 | |

|

| |||||||

| Adaptive | IL-15 | 1.54 | 0.30 – 1.90 | 2.08 | 1.39 – 2.52 | −0.240 (0.114) | 0.038 |

| IL-5 | 0.03 | 0.02 – 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 – 0.04 | 0.011 (0.028) | 0.690 | |

| IL-17 | 0.82 | 0.03 – 1.17 | 1.07 | 0.67 – 1.73 | −0.158 (0.137) | 0.251 | |

| sCD40L | 22.84 | 8.41 – 30.89 | 22.84 | 12.64 – 33.53 | −0.007 (0.113) | 0.954 | |

| IFN-γ | 1.31 | 0.13 – 4.51 | 0.67 | 0.01 – 3.09 | 0.336 (0.215) | 0.121 | |

| IL-2† | 0.08 | 0.01 – 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.01 – 0.19 | −0.444 (0.417) | 0.287 | |

| IL-4† | 0.02 | 0.02 – 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.02 – 0.38 | −0.300 (0.406) | 0.460 | |

| IL-13† | 0.01 | 0.01 – 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 – 0.01 | 0.217 (0.428) | 0.612 | |

| sIL-2Rα† | 5.88 | 0.57 – 10.13 | 6.10 | 0.57 – 10.70 | 0.143 (0.395) | 0.717 | |

|

| |||||||

| Anti-inflammatory | IL-1Ra | 36313.59 | 26674.06 – 45012.00 | 40793.38 | 27693.84 – 45012.00 | −0.038 (0.044) | 0.381 |

| IL-10† | 0.02 | 0.01 – 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.01 – 0.24 | 0.813 (0.429) | 0.058 | |

|

| |||||||

| MMPs | MMP-1 | 5.30 | 2.40 – 42.71 | 3.92 | 2.40 – 53.10 | 0.135 (0.179) | 0.454 |

| MMP-7 | 5038.05 | 379.42 – 23761.51 | 2247.97 | 162.27 – 26476.16 | 0.293 (0.358) | 0.416 | |

| MMP-9 | 13336.27 | 4963.64 – 73603.95 | 15753.28 | 4774.88 – 46728.84 | 0.203 (0.202) | 0.318 | |

| MMP-10 | 11.70 | 2.20 – 126.18 | 5.52 | 2.20 – 166.11 | 0.318 (0.235) | 0.180 | |

| MMP-2† | 118.10 | 118.10 – 118.10 | 118.10 | 118.10 – 118.10 | 0.808 (0.832) | 0.332 | |

|

| |||||||

| TIMPs | TIMP-1 | 1867.65 | 854.01 – 6087.20 | 4356.19 | 1316.85 – 6634.26 | −0.243 (0.189) | 0.203 |

| TIMP-2 | 11759.57 | 6497.84 – 16406.50 | 14878.22 | 8023.87 – 19246.30 | −0.207 (0.091) | 0.027 | |

| TIMP-3 | 25.45 | 25.45 – 32.54 | 25.45 | 25.45 – 32.54 | 0.029 (0.040) | 0.472 | |

| TIMP-4 | 3.92 | 3.92 – 3.92 | 3.92 | 3.92 – 3.92 | 0.013 (0.068) | 0.849 | |

SE=standard error, CI = confidence interval.

Multivariate analysis adjusted for age, marital status, condom use, sex work, STIs and BV as co-variates.

Variables with at least a third of concentrations were undetectable were dichotomised and a logistic regression model was fitted to estimate the effect of injectable contraception on detectability of these cytokines

3.3 Impact of BV and STIs on cytokines in injectable HC versus non-HC users

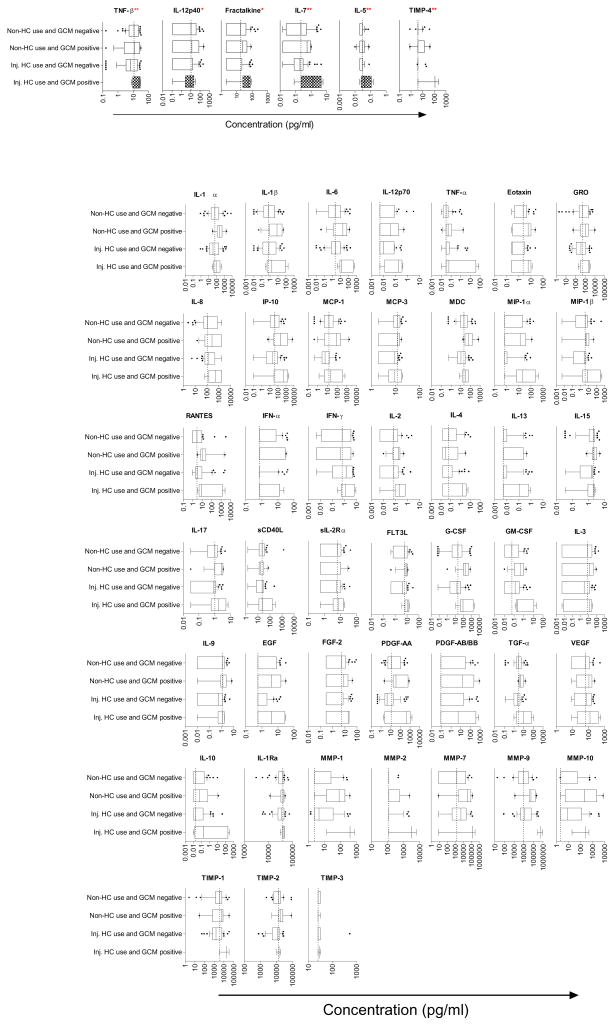

Because we found that injectable HC use resulted in lower median concentration of genital tract cytokines from several different functional classes (Table 2), we assessed whether there were interactions between injectable HCs and cytokine concentrations in responses to BV or STIs in the female genital tract. We did not observe any significant interactions between injectable HC use and cytokine responses to BV (Supplementary Table 1). T. vaginalis also had a limited interaction with injectable HC, with only Flt3L demonstrating a significant result (β-estimate of −0.194 in the injectable group vs 0.338 in the non-injectable group, p=0.048, Supplementary Table 2). However, we found significant interactions between gonorrhea, chlamydia or mycoplasma (GCM) infections and injectable HC use for certain cytokines, with TNF-β (p=0.022), IL-5 (p=0.015), IL-7 (p=0.036) and TIMP-4 (p=0.003), with GCM positive women on injectable HC having increased median concentrations of these cytokines in the CVL, compared to the effect of GCM positivity on cytokine concentrations within the non-HC users (Figure 1, supplementary Table 3). Furthermore, IL-12p40 (p=0.061) and Fractalkine (p=0.069) showed a trend towards being elevated in the GCM positive women using injectable HCs compared to non-HC users. However, none of these associations remained significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons.

Figure 1.

Cytokine concentrations in cervicovaginal lavages (CVLs) from women using injectable HCs (DMPA or Net-EN) compared to those not using HCs, stratified according to presence of discharge causing STIs (C. trachomatis, N. gonnorhoea, M. genitalium; GCM). Dotted lines indicate the median concentration of each cytokine, MMP or TIMP in women not using HCs and who were GCM negative, as the reference group. ** indicates significant interactions between injectable HC use and GCM with p<0.05, while * indicates interactions between injectable HC use and GCM with p<0.10.

4.0 Discussion

We found that median concentrations of several cytokines and soluble factors (including several chemokines, pro-inflammatory and adaptive cytokines, growth factors and TIMP were reduced in CVLs of women using injectable HC compared to women who were not using HC, after controlling for age, condom use, sex work, STIs and BV. Despite this reduction of innate immune responses in the female genital tracts of women using injectable HCs, no differences in prevalence of BV, or STIs (including C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoea, T. vaginalis, M. genitalium, or HSV-2) were found.

Although some animal studies using high dose DMPA, have demonstrated that DMPA has immunosuppressive properties both systemically and in the reproductive tract (Abel et al., 2004, Bamberger et al., 1999, Genesca et al., 2007, Gillgrass et al., 2003, Hel et al., 2010, Hughes et al., 2008, Huijbregts et al., 2013, Kleynhans et al., 2013, Kleynhans et al., 2011, Koubovec et al., 2004, Trunova et al., 2006), fewer studies have been conducted in humans and these have predominantly been performed using PBMCs (Hughes et al., 2008, Kleynhans et al., 2011). With the exception of Huijbregts et al. (2013) who reported reduced cervicovaginal production of IFN-α in women using injectable HCs, the other human studies suggested that DMPA use may actually increase inflammation within the female genital tract (Baeten et al., 2001, Ghanem et al., 2005). In this study, decreased chemotactic cytokine (including eotaxin, fractalkine, MCP-1 and MDC in the multivariate analyses) concentrations observed in women using HCs might influence the trafficking of immune cells to the female genital tract. Fractalkine has been reported to play a role to the recruitment of immune cells to the endometrium, which may be influenced by the presence of DMPA (Hannan et al., 2004). Although these associations potentially suggest HC interference with chemotaxis, we have not done the mechanistic studies necessary to test the relationship between HCs and trafficking of cells within genital tissues.

In our interaction term analysis, we hypothesized that HC use had a limited impact on cytokine responses to trichomoniasis and gonorrhea, chlamydia and mycoplasma infections, but did not modify the relationship between cytokine concentrations and BV. This analysis suggested that women with gonorrhea, chlamydia and mycoplasma (GCM) infections who were using HCs had greater increases in the concentrations of TNF-β, IL-5, IL-7, TIMP-4, IL-12p40 and Fractalkine relative to women with GCM infections who were not using HCs. In addition, we found that the effect size of the relationship between T. vaginalis and Flt3L concentrations was larger in women using injectable HCs compared to non-HC users. However, these associations should be interpreted conservatively as none of these associations was significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons and sample sizes for these analyses were relatively small.

High dose DMPA administration to macaques is associated with thinning of the vaginal epithelium (Abel et al., 2004, Genesca et al., 2007, Trunova et al., 2006, Wieser et al., 2001). In this study, significantly reduced concentrations of PDGF-AA were found in CVL from women using injectable HC compared to women not using injectable HCs. This growth factor has been reported to play an important role in restoring the barrier function of the female genital tract following injury, and reduced expression may influence the ability of the epithelial barrier to be regenerated and repaired (Werner and Grose, 2003). Growth factors enhance epithelial repair by stimulating mitosis, spreading and migration of epithelial cells in mouse airways (Werner and Grose, 2003), and as such, a decrease in these factors could lead to weakened epithelial barriers and reduced epithelial healing in women using injectable HCs.

MMPs and TIMPs play an important role in the degradation and remodeling of the extracellular matrix in the upper reproductive tract during normal reproductive processes (Lockwood and Schatz, 1996, Rodgers et al., 1994, Rodgers et al., 1993, Birkedal-Hansen, 1995, Cawston, 1995). Previous studies have shown that progesterone suppresses the epithelial cell-specific MMPs, working cooperatively with TGF-β to regulate epithelial-specific MMP-7 expression (Bruner et al., 1995, Osteen et al., 1994). In contrast, in the lower reproductive tract, we found no difference between MMP concentrations in women using injectable HCs compared to those who were not using HC. Previously, Vincent et al. (2002) found that women using DMPA had decreased TIMP-1 and -2 concentrations in their endometrial epithelium and an altered local MMP:TIMP balance in their upper reproductive tracts compared to women not using HCs. Similarly, we found decreased TIMP-2 concentrations in secretions from the lower reproductive tracts of women using injectable HC compared to those not using HCs. Reduced concentrations of TIMPS may alter the MMP/TIMP ratio which could lead to decreased epithelial barrier integrity.

A limitation of our study is that we could not differentiate DMPA from Net-EN users within the injectable HC user group although these progestin-based HCs may have distinct biological effects. DMPA or NET-EN users may differ behaviourally or systematically from women who do not any hormonal contraceptives. In addition, we did not monitor the stage of the menstrual cycle in this cohort, nor collect longitudinal data on DMPA or NET-EN use prior sampling. This study did not adjust CVL for dilution so absolute concentrations of cytokines may have been influenced by this factor.

5.0 Conclusion

We found reductions in CVL concentrations of one proinflammatory cytokine, four chemokines, one growth factor, one adaptive cytokine and one TIMP in the lower female genital tract of women using injectable HCs. While we are underpowered to demonstrate the relationship between injectable HC use and STI or HIV risk, our data suggest that injectable HCs effects were similar between STI positive and STI negative participants. Large-scale randomized clinical trials assessing the impact of progestin-derivatives (DMPA or Net-EN) on local and systemic innate and adaptive immune environment, as well as STIs, are needed to further investigate the mechanism(s) by which DMPA or Net-EN might increase risk of HIV infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants from the Poliomyelitis Research Foundation (PRF) of South Africa. The parent trial (CAPRISA 002) was supported by the Comprehensive International Program of Research on AIDS (CIPRA) funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH), the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) (grant #1 U19 AI51794) and the National Research Foundation (grant # 67385). SN, LM, MS, JAP and SS were supported by Columbia University-Southern African Fogarty AITRP Program (grant # D43TW00231).

References

- ABEL K, ROURKE T, LU D, BOST K, MCCHESNEY MB, MILLER CJ. Abrogation of attenuated lentivirus-induced protection in rhesus macaques by administration of depo-provera before intravaginal challenge with simian immunodeficiency virus mac239. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1697–705. doi: 10.1086/424600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAETEN JM, BENKI S, CHOHAN V, LAVREYS L, MCCLELLAND RS, MANDALIYA K, NDINYA-ACHOLA JO, JAOKO W, OVERBAUGH J. Hormonal contraceptive use, herpes simplex virus infection, and risk of HIV-1 acquisition among Kenyan women. AIDS. 2007;21:1771–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328270388a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAETEN JM, NYANGE PM, RICHARDSON BA, LAVREYS L, CHOHAN B, MARTIN HL, JR, MANDALIYA K, NDINYA-ACHOLA JO, BWAYO JJ, KREISS JK. Hormonal contraception and risk of sexually transmitted disease acquisition: results from a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:380–5. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.115862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAMBERGER CM, ELSE T, BAMBERGER AM, BEIL FU, SCHULTE HM. Dissociative glucocorticoid activity of medroxyprogesterone acetate in normal human lymphocytes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4055–61. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.11.6091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BHATHENA RK. The long-acting progestogen-only contraceptive injections: an update. BJOG. 2001;108:3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIRKEDAL-HANSEN H. Proteolytic remodeling of extracellular matrix. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:728–35. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRUNER KL, RODGERS WH, GOLD LI, KORC M, HARGROVE JT, MATRISIAN LM, OSTEEN KG. Transforming growth factor beta mediates the progesterone suppression of an epithelial metalloproteinase by adjacent stroma in the human endometrium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7362–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAWSTON TE. Proteinases and inhibitors. Br Med Bull. 1995;51:385–401. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, M. R. C., ORCMACRO. South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Pretoria, South Africa: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ELDER MG. Injectable contraception. Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1984;11:723–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERNANDEZ-CATALAN C, BODE W, HUBER R, TURK D, CALVETE JJ, LICHTE A, TSCHESCHE H, MASKOS K. Crystal structure of the complex formed by the membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase with the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2, the soluble progelatinase A receptor. EMBO J. 1998;17:5238–48. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.5238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRASER IS, WEISBERG E. A comprehensive review of injectable contraception with special emphasis on depot medroxyprogesterone acetate. Med J Aust. 1981;1:3–19. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1981.tb135992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GENESCA M, LI J, FRITTS L, CHOHAN P, BOST K, ROURKE T, BLOZIS SA, MCCHESNEY MB, MILLER CJ. Depo-Provera abrogates attenuated lentivirus-induced protection in male rhesus macaques challenged intravenously with pathogenic SIVmac239. J Med Primatol. 2007;36:266–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.2007.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHANEM KG, SHAH N, KLEIN RS, MAYER KH, SOBEL JD, WARREN DL, JAMIESON DJ, DUERR AC, ROMPALO AM, GROUP HIVERS. Influence of sex hormones, HIV status, and concomitant sexually transmitted infection on cervicovaginal inflammation. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:358–66. doi: 10.1086/427190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILLGRASS AE, ASHKAR AA, ROSENTHAL KL, KAUSHIC C. Prolonged exposure to progesterone prevents induction of protective mucosal responses following intravaginal immunization with attenuated herpes simplex virus type 2. J Virol. 2003;77:9845–51. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.18.9845-9851.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOMIS-RUTH FX, MASKOS K, BETZ M, BERGNER A, HUBER R, SUZUKI K, YOSHIDA N, NAGASE H, BREW K, BOURENKOV GP, BARTUNIK H, BODE W. Mechanism of inhibition of the human matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-1 by TIMP-1. Nature. 1997;389:77–81. doi: 10.1038/37995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANNAN NJ, JONES RL, CRITCHLEY HO, KOVACS GJ, ROGERS PA, AFFANDI B, SALAMONSEN LA. Coexpression of fractalkine and its receptor in normal human endometrium and in endometrium from users of progestin-only contraception supports a role for fractalkine in leukocyte recruitment and endometrial remodeling. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:6119–29. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEFFRON R, DONNELL D, REES H, CELUM C, MUGO N, WERE E, DE BRUYN G, NAKKU-JOLOBA E, NGURE K, KIARIE J, COOMBS RW, BAETEN JM. Use of hormonal contraceptives and risk of HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2012;12:19–26. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70247-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEL Z, STRINGER E, MESTECKY J. Sex steroid hormones, hormonal contraception, and the immunobiology of human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. Endocrine reviews. 2010;31:79–97. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUGHES GC, THOMAS S, LI C, KAJA MK, CLARK EA. Cutting edge: progesterone regulates IFN-alpha production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Journal of Immunology. 2008;180:2029–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUIJBREGTS RP, HELTON ES, MICHEL KG, SABBAJ S, RICHTER HE, GOEPFERT PA, HEL Z. Hormonal contraception and HIV-1 infection: medroxyprogesterone acetate suppresses innate and adaptive immune mechanisms. Endocrinology. 2013;154:1282–95. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ILDGRUBEN AK, SJOBERG IM, HAMMARSTROM ML. Influence of hormonal contraceptives on the immune cells and thickness of human vaginal epithelium. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:571–82. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00618-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JEPPSSON S, GERSHAGEN S, JOHANSSON ED, RANNEVIK G. Plasma levels of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), sex-hormone binding globulin, gonadal steroids, gonadotrophins and prolactin in women during long-term use of depo-MPA (Depo-Provera) as a contraceptive agent. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1982;99:339–43. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0990339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIDDUGAVU M, MAKUMBI F, WAWER MJ, SERWADDA D, SEWANKAMBO NK, WABWIRE-MANGEN F, LUTALO T, MEEHAN M, XIANBIN, GRAY RH RAKAI PROJECT STUDY G. Hormonal contraceptive use and HIV-1 infection in a population-based cohort in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS. 2003;17:233–40. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200301240-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEINSCHMIDT I, REES H, DELANY S, SMITH D, DINAT N, NKALA B, MCINTYRE JA. Injectable progestin contraceptive use and risk of HIV infection in a South African family planning cohort. Contraception. 2007;75:461–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEYNHANS L, DU PLESSIS N, ALLIE N, JACOBS M, KIDD M, VAN HELDEN PD, WALZL G, RONACHER K. The contraceptive depot medroxyprogesterone acetate impairs mycobacterial control and inhibits cytokine secretion in mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2013;81:1234–44. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01189-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEYNHANS L, DU PLESSIS N, BLACK GF, LOXTON AG, KIDD M, VAN HELDEN PD, WALZL G, RONACHER K. Medroxyprogesterone acetate alters Mycobacterium bovis BCG-induced cytokine production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of contraceptive users. PloS One. 2011;6:e24639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOUBOVEC D, VANDEN BERGHE W, VERMEULEN L, HAEGEMAN G, HAPGOOD JP. Medroxyprogesterone acetate downregulates cytokine gene expression in mouse fibroblast cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;221:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUMWENDA JJ, MAKANANI B, TAULO F, NKHOMA C, KAFULAFULA G, LI Q, KUMWENDA N, TAHA TE. Natural history and risk factors associated with early and established HIV type 1 infection among reproductive-age women in Malawi. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46:1913–20. doi: 10.1086/588478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOCKWOOD CJ, SCHATZ F. A biological model for the regulation of peri-implantational hemostasis and menstruation. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 1996;3:159–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARX PA, SPIRA AI, GETTIE A, DAILEY PJ, VEAZEY RS, LACKNER AA, MAHONEY CJ, MILLER CJ, CLAYPOOL LE, HO DD, ALEXANDER NJ. Progesterone implants enhance SIV vaginal transmission and early virus load. Nature medicine. 1996;2:1084–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER L, PATTON DL, MEIER A, THWIN SS, HOOTON TM, ESCHENBACH DA. Depomedroxyprogesterone-induced hypoestrogenism and changes in vaginal flora and epithelium. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:431–9. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00906-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MLISANA K, NAICKER N, WERNER L, ROBERTS L, VAN LOGGERENBERG F, BAXTER C, PASSMORE JA, GROBLER AC, STURM AW, WILLIAMSON C, RONACHER K, WALZL G, ABDOOL KARIM SS. Symptomatic vaginal discharge is a poor predictor of sexually transmitted infections and genital tract inflammation in high-risk women in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:6–14. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORRISON CS, CHEN PL, KWOK C, RICHARDSON BA, CHIPATO T, MUGERWA R, BYAMUGISHA J, PADIAN N, CELENTANO DD, SALATA RA. Hormonal contraception and HIV acquisition: reanalysis using marginal structural modeling. AIDS. 2010;24:1778–81. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MYER L, DENNY L, WRIGHT TC, KUHN L. Prospective study of hormonal contraception and women’s risk of HIV infection in South Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:166–74. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSTEEN KG, RODGERS WH, GAIRE M, HARGROVE JT, GORSTEIN F, MATRISIAN LM. Stromal-epithelial interaction mediates steroidal regulation of metalloproteinase expression in human endometrium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10129–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.10129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REID SE, DAI JY, WANG J, SICHALWE BN, AKPOMIEMIE G, COWAN FM, DELANY-MORETLWE S, BAETEN JM, HUGHES JP, WALD A, CELUM C. Pregnancy, contraceptive use, and HIV acquisition in HPTN 039: relevance for HIV prevention trials among African women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53:606–13. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bc4869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RODGERS WH, MATRISIAN LM, GIUDICE LC, DSUPIN B, CANNON P, SVITEK C, GORSTEIN F, OSTEEN KG. Patterns of matrix metalloproteinase expression in cycling endometrium imply differential functions and regulation by steroid hormones. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:946–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI117461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RODGERS WH, OSTEEN KG, MATRISIAN LM, NAVRE M, GIUDICE LC, GORSTEIN F. Expression and localization of matrilysin, a matrix metalloproteinase, in human endometrium during the reproductive cycle. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:253–60. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(12)90922-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIBEKO S, BAXTER C, YENDE N, KARIM QA, KARIM SS. Contraceptive choices, pregnancy rates, and outcomes in a microbicide trial. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2011;118:895–904. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822be512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRINGER EM, GIGANTI M, CARTER RJ, EL-SADR W, ABRAMS EJ, STRINGER JS, INITIATIVE MTP. Hormonal contraception and HIV disease progression: a multicountry cohort analysis of the MTCT-Plus Initiative. AIDS. 2009;23(Suppl 1):S69–77. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000363779.65827.e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRUNOVA N, TSAI L, TUNG S, SCHNEIDER E, HAROUSE J, GETTIE A, SIMON V, BLANCHARD J, CHENG-MAYER C. Progestin-based contraceptive suppresses cellular immune responses in SHIV-infected rhesus macaques. Virology. 2006;352:169–77. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNGCHUSAK K, REHLE T, THAMMAPORNPILAP P, SPIEGELMAN D, BRINKMANN U, SIRAPRAPASIRI T. Determinants of HIV infection among female commercial sex workers in northeastern Thailand: results from a longitudinal study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 1996;12:500–7. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199608150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DE WIJGERT JH, VERWIJS MC, TURNER AN, MORRISON CS. Hormonal contraception decreases bacterial vaginosis but oral contraception may increase candidiasis: implications for HIV transmission. AIDS. 2013;27:2141–53. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32836290b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN LOGGERENBERG F, DIETER AA, SOBIESZCZYK ME, WERNER L, GROBLER A, MLISANA K. HIV prevention in high-risk women in South Africa: condom use and the need for change. PloS One. 2012;7:e30669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WERNER S, GROSE R. Regulation of wound healing by growth factors and cytokines. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:835–70. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2003.83.3.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIESER F, HOSMANN J, TSCHUGGUEL W, CZERWENKA K, SEDIVY R, HUBER JC. Progesterone increases the number of Langerhans cells in human vaginal epithelium. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:1234–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01796-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIRA CR, GHOSH M, SMITH JM, SHEN L, CONNOR RI, SUNDSTROM P, FRECHETTE GM, HILL ET, FAHEY JV. Epithelial cell secretions from the human female reproductive tract inhibit sexually transmitted pathogens and Candida albicans but not Lactobacillus. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:335–42. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIRA CR, VERONESE F. Mucosal immunity in the male and female reproductive tract and prevention of HIV transmission. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2011;65:182–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00976.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.