Abstract

Background

Pre-hospital paediatric airway management is complex. A variety of pitfalls need prompt response to establish and maintain adequate ventilation and oxygenation. Anatomical disparity render laryngoscopy different compared to the adult. The correct choice of endotracheal tube size and depth of insertion is not trivial and often challenged due to the initially unknown age of child.

Methods

Data from 425 paediatric patients (<17 years of age) with any airway manipulation treated by a Swiss Air-Ambulance crew between June 2010 and December 2013 were retrospectively analysed. Endpoints were: 1) Endotracheal intubation success rate and incidence of difficult airway management in primary missions. 2) Correlation of endotracheal tube size and depth of insertion with patient’s age in all (primary and secondary) missions.

Results

In primary missions, the first laryngoscopy-guided endotracheal intubation attempt was successful in 95.3% of cases, with an overall success rate of 98.6%. Difficult airway management was reported in 10 (4.7%) patients. Endotracheal tube size was frequently chosen inadequately large (overall 50 of 343 patients: 14.6%), especially and statistically significant in the age group below 1 year (19 of 33 patients; p < 0.001). Tubes were frequently and distinctively more deeply inserted (38.9%) than recommended by current formulae.

Conclusion

Difficult airway management, including cannot intubate and cannot ventilate situations during pre-hospital paediatric emergency treatment was rare. In contrast, the success rate of endotracheal intubation at the first attempt was very high. High numbers of inadequate endotracheal tube size and deep placement according to patient age require further analysis. Practical algorithms need to be found to prevent potentially harmful treatment.

Keywords: Paediatric airway, Pre-hospital airway, Emergency airway, Endotracheal tube size and depth, HEMS

Background

Pre-hospital paediatric airway management is complex. Different pitfalls such as anatomical airway obstruction (poorly positioned head, inappropriate facemask usage or tonsillar hypertrophy) and functional airway obstruction (laryngospasm, bronchospasm or opioid induced thorax rigidity) need to be quickly recognized during bag mask ventilation. Prompt response to these problems is necessary to maintain adequate ventilation and oxygenation due to the known low functional residual capacity in new born and young children resulting in rapid hypoxaemia during apnoea [1, 2]. Regarding endotracheal intubation (ETI), a smaller oral cavity with a relatively large tongue, a more anterior larynx, a higher glottis and a longer epiglottis render laryngoscopy different compared to the adult anatomy [3].

Pre-hospital ETI by paramedics had high levels of misplacement (into the oesophagus or the hypopharynx) combined with a high mortality and morbidity rate [4], especially in the absence of end tidal carbon dioxide measurement [4–7]. Rates of successful ETI varied depending on the investigated patient group and the qualification of the intubating health care provider [8–12]. The ETI success rate for pre-hospital paediatric patients lies between 55 and 100% [13], with a high complication rate (unrecognised oesophageal intubation 14.6%, incorrect endotracheal (ET) tube size/depth of insertion 11–22%, cardiovascular collapse with consecutive need for resuscitation after ETI, potentially “lethal” ventilator settings 4.9%, inability to intubate 35%) in less experienced emergency medical service health care providers [14–16]. ETI can be more difficult in a pre-hospital setting, with a higher grading, according to Cormack and Lehane [17] and a higher incidence of difficult and failed laryngoscopy and airway management [18]. Others report pre-hospital ETI success rates are comparable to the in-hospital rate, especially if performed by highly skilled physicians [19].

The choice of the adequate ET tube size and depth of insertion is not trivial. Circumstances such as initially unknown age often jeopardize adequate airway management. In a former study, intubation depth in a helicopter emergency service (HEMS) was incorrect in 57% of paediatric ETI [20]. Since then, novel philosophies towards the use of cuffed paediatric ET tubes changed the practice among HEMS, making a new evaluation of the current routine necessary. Commonly used age-based formulae for ET tube size calculation are inappropriate in 20–30% of cases [21, 22]. With cuffed ET tubes it is possible to choose the correct ET tube size in almost 100% of patients, if the child’s age is known [23–25]. Small for age ET tube sizes can lead to an increase in airway resistance, but may have to be chosen intentionally if a narrow airway is clinically expected (oedema, trauma). If chosen too large, ET tubes may lead to pressure points on the tracheal mucosa followed by oedema or necrosis [22, 26, 27]. Correct intubation depth is critical as small amounts of motion can lead to supraglottic or endobronchial misplacement [28–30]. Head-neck flexion moves the ET tube further down into the trachea (9.7 to 20 mm), whereas 30° head-neck extension pulls the ET tube back (9.8 to 22 mm) [28]. The consequence is a small margin of safety concerning depth of ET tube placement. Clinical assessment of the correct ET tube depth is difficult without the help of concluding imaging, because auscultation can be misleading and inconclusive in a noisy pre-hospital setting. Defining correct intubation depth solely on formula based calculations can lead to incorrect placement [31, 32]. A study by Weiss et al. pinpointed that only visual placement of the Microcuff ET tube marking between the vocal cords leads to a correct tracheal positioning of the ET tube tip in all of the investigated children in an in-hospital setting [31, 33].

The aims of this study were to evaluate the incidence of difficult airways and the ETI success rate on primary missions and to monitor ET tube size and depth of insertion in paediatric patients treated by a Swiss HEMS.

Methods

Ethics

The data analysis was approved by the local ethics committee (Kantonale Ethikkommission Zurich, Switzerland, KEK-ZH-2014-0067).

Study design and participants

Retrospective observational study including all paediatric patients (< 17 years of age) with any airway manipulation (bag mask ventilation, ETI, supraglottic airway or tracheotomy) treated by a Swiss Air-Ambulance (Rega) crew between June 2010 and December 2013.

Setting

The Swiss Air-Ambulance (Rega) is a non-profit HEMS that performs more than 11.000 emergency missions per year from 12 bases and one partner-base in Switzerland. Operation profiles comprise primary missions (scene to hospital) and secondary missions (hospital to hospital) with all types of emergencies (medical, trauma and evacuations) and patient characteristics. Patients transported from hospital to hospital (secondary mission) in this study, had already been intubated by the referring hospital staff prior to our HEMS transfer.

The Rega HEMS crew consists of a helicopter pilot, a paramedic and a specially trained emergency physician. These physicians are to be on the anaesthesia track (> 1 year), experienced in emergency medicine (> 4 years in total, advanced cardiovascular and trauma life support providers approved by the American Heart Association or the European Resuscitation Council), paediatric anaesthesia (paediatric advanced life support providers), and intensive care (3–6 months). The Rega standard advanced paediatric airway management is ETI performed as a controlled rapid sequence induction and intubation without obligation to omit mask ventilation prior to ETI as described by Neuhaus et al. [34]. The equipment is standardised throughout the entire organisation. Available neuromuscular blocking agents are rocuronium bromide and suxamethonium chloride. Rega used Microcuff ET tubes (Kimberly-Clark Health Care Europe, Zaventem, Belgium) with internal diameters from 3 to 5 mm, in 0.5 mm increments and Rusch super safety clear tubes (Teleflex Medical Europe Ltd, Athlone, Ireland) with internal diameters of 6–8 mm respectively. All ET tubes in this study contained a cuff. Laryngeal masks unique™ (LMA, Bonn, Germany) were used by the Rega as primary supraglottic (alternative) airway devices. In this study, also laryngeal tubes (VBM Germany, Sulz a.N., Germany) were used by first responders prior to Rega arrival.

Descriptive variables

Demographic data of the patient (age and gender), mission characteristics (primary and secondary), emergency specifications (national advisory committee for aeronautics (NACA) score, Glasgow coma scale (GCS) and type of emergency) and detailed information about airway management (indication, type of airway management, number of laryngoscopic attempts to accomplish ETI, ET tube size, depth of insertion, use of alternative airway equipment, use of capnography and neuromuscular blocking agents) were recorded.

Endpoints and outcome variables

Endpoints were: 1) ETI success rate and incidence of difficult airway management reported by the treating physician in primary missions. 2) Correlation of ET tube size and depth of insertion with patient’s age in all (primary and secondary) missions. ETI was successful if expiratory carbon dioxide was detected by capnography.

Throughout this manuscript we used a 15% tolerance concerning ET tube size and depth of insertion as published data shows this relative distance from the ET tube tip to the carina in the shortest trachea per age group [31]. The adequate ET tube size according to patient’s age was defined by the manufacturer (Kimberly-Clark Health Care Europe, Zaventem, Belgium). Thus (including the tolerance) until the age of 8 months, only a 3.0 ET tube size was judged as adequate, from 8 months until 14 years of age the recommended size +/− 0.5 mm, and from 14 to < 17 years the recommended size +/− 1 mm was judged as adequate. ET tube depth of insertion was measured from the front teeth to the tube tip. The measured value was compared to age-based calculations by Weiss et al. (10.612 + age [years] × 0.5493 in cm) [31] and a standard formula for oral ET tube depth of insertion (12 + age [years] × 0.5 in cm) for children over 2 years of age [35].

Data collection

Relevant missions were identified in the Rega database. Data on mission and patient characteristics was extracted from that database. Thereafter, the corresponding original HEMS protocols were analysed and data on airway management was extracted. The data was transferred into a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel: mac 2011, version 13.5.3, Microsoft corporation, Redmond, USA).

Bias

As obliged by the Swiss aviation authorities, the Rega database contains every helicopter movement. These movements are distinctively linked to mandatory information on patient’s characteristics and on the information about airway management, which limits the influence of selection bias. The analysed HEMS protocols were completed directly at the end of every mission by the responsible emergency physician, narrowing the effect of a recall bias.

Statistical methods

Statistical data was analysed with the SPSS software (Version 22, IBM, Armonk NY, USA) in collaboration with the Division of Biostatistics from the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (University of Zurich). For non-normally distributed independent variables we used the “Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney” test. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.01 was considered statistically significant. Chi square test was used to test independence of normally distributed data. Ordinal or skewed data was presented as median and interquartile range (IQR).

Results and Discussion

In total, 4505 paediatric patients were treated by Rega HEMS crews during the study period. The study population consisted of 425 children with any airway manipulation. Of the performed helicopter missions, 225 (52.9%) were at the scene (primary) and 200 (47.1%) were secondary transports between hospitals of already ventilated patients (intubated prior to the mission). In all patients the method of airway management could be determined. Most commonly the children’s airway was secured with an ET tube. Capnography was used in all intubated patients to confirm ET tube position in the trachea. Details on patient, airway and mission characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient, mission and airway characteristics

| Primary mission | Secondary mission | |

|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 425) | 225 | 200 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 142 (63.1%) | 115 (57.7%) |

| Age | ||

| median (IQR) | 6.4 (2.4–12.7) | 5 (1.7–10.5) |

| NACA | ||

| III | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| IV | 31 (13.8%) | 75 (37.5%) |

| V | 116 (51.6%) | 116 (58%) |

| VI | 43 (19.1%) | 8 (4%) |

| VII | 34 (15.1%) | 0 |

| GCS | ||

| < 9 | 206 (91.5%) | 184 (92%) |

| > = 9 | 19 (8.5%) | 16 (8%) |

| Trauma | 151 (67.1%) | 69 (34.5%) |

| Craniofacial injury | 117 (77.5%) | 55 (79.7%) |

| Other | 34 (22.5%) | 14 (20.3%) |

| Non-trauma | 74 (32.9%) | 131 (65.5%) |

| Neurological | 20 (27%) | 40 (30.5%) |

| Respiratory | 37 (50%) | 12 (9.2%) |

| Circulatory | 13 (17.6%) | 53 (40.5%) |

| Other | 4 (5.4%) | 26 (19.8%) |

| Airway (final) | ||

| NIV | 4 (1.8%) | 5 (2.5%) |

| Tracheotomy (pre-existing) | 3 (1.3%) | 5 (2.5%) |

| Orotracheal int. | 212 (94.2%) | 172 (86%) |

| Nasotracheal int. | 0 | 18 (9%) |

| Laryngeal mask | 2 (0.9%) | 0 |

| Laryngeal tube | 3 (1.3%) | 0 |

| CICV | 1 (0.4%) | n/a |

| Neuromuscular blocking agents used (NACA III-V) | 129/148 (87.2%) | n/a |

| Rocuronium | 34 (26.4%) | |

| Suxamethonium | 95 (73.6%) | |

| Neuromuscular blocking agents used (NACA VI-VII) | 11/77 (13.3%) | n/a |

| Rocuronium | 6 (54.5%) | |

| Suxamethonium | 5 (45.5%) |

Summary of primary and secondary mission characteristics. Percentages are in reference to the main group (primary/secondary) or the subgroup respectively. IQR interquartile range. NACA national advisory committee for aeronautics. GCS glasgow coma scale. NIV non-invasive ventilation. CICV cannot intubate, cannot ventilate

ETI success rate and incidence of difficult airway management in primary missions

In 215 patients an orotracheal on-scene ETI was attempted. The first laryngoscopy-guided ETI effort was successful in 205 (95.3%) patients. Difficult airway management was described by the treating physician in ten (4.7%) patients: Seven (3.3%) patients required 2–4 laryngoscopies until their trachea could be intubated (three resuscitations, four severe craniofacial injuries), resulting in a 98.6% overall ETI success rate. Cannot intubate (CI) situations were rare but present in three cases (1.4%), two of them because of blood in the traumatised airway. Both could be managed with a laryngeal mask. One cannot intubate, cannot ventilate (CICV) situation in a patient with obvious dysmorphia syndrome (Goldenhar) was encountered during an already long-lasting hypoxic cardiovascular resuscitation. Prolongation of the resuscitation efforts was judged as inadequate and the patient was declared dead.

Correlation of ET tube size with patient’s age in all missions

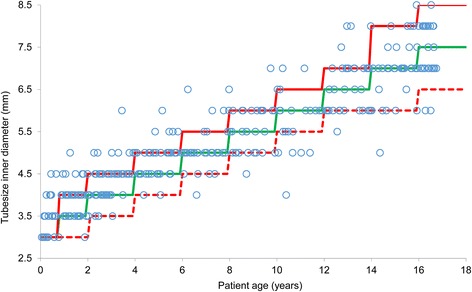

Among all orotracheal intubated children (n = 384), ET tube size was noted in 343 (82.7%) of the protocols. Thereof, the chosen ET tube size was adequate in 82.5%, inadequately small in 2.9% and inadequately large in 14.6%, especially and statistically significant in the age group of new born to 1 year (19 of 33 children; p < 0.001; Fig. 1, Table 2). Children with an inadequate ET tube size were significantly younger than children with an adequate ET tube size: 3.4 (0.6 – 9.9) vs. 5.4 (2.8 – 13.5) years, (p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Chosen endotracheal tube (size of inner diameter in mm) for patient age (years). Adequate tube size for age is shown as the continuous green line, 15% upper tolerance limit as the continuous red line and 15% lower tolerance limit as the dashed red line. Adequate tube size in 82.5%, inadequately small in 2.9% inadequately large in 14.6%

Table 2.

Adequate oral endotracheal tube sizes according to sub groups

| Adequate | Inadequate (small) | Inadequate (large) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female (n = 133) | 107 (80.5%) | 6 (4.5%) | 20 (15%) | p = 0.467 |

| Male (n = 210) | 176 (83.8%) | 4 (1.9%) | 30 (14.3%) | |

| Age in years | ||||

| 0–1 (n = 33) | 14 (42.4%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (57.6%) | p < 0.001 |

| 1–2 (n = 37) | 30 (81.1%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (18.9%) | |

| 2–4 (n = 56) | 49 (87.5%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (12.5%) | |

| 4–6 (n = 37) | 32 (86.5%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (13.5%) | |

| 6–8 (n = 32) | 27 (84.4%) | 1 (3.1%) | 4 (12.5%) | |

| 8–10 (n = 30) | 27 (90%) | 2 (6.7%) | 1 (3.3%) | |

| 10–12 (n = 21) | 14 (66.7%) | 5 (23.8%) | 2 (9.5%) | |

| 12–17 (n = 97) | 90 (92.8%) | 2 (2.1%) | 5 (5.1%) | |

| Mission type | ||||

| Primary (n = 195) | 165 (84.6%) | 7 (3.6%) | 23 (11.8%) | p = 0.253 |

| Secondary (n = 148) | 118 (79.7%) | 3 (2.1%) | 27 (18.2%) | |

| Medical indication | ||||

| Trauma (n = 194) | 166 (85.6%) | 6 (3.1%) | 22 (11.3%) | p = 0.114 |

| Non-trauma (n = 149) | 117 (78.5%) | 4 (2.7%) | 28 (18.8%) | |

| Resuscitation | ||||

| Yes (n = 72) | 53 (73.6%) | 5 (6.9%) | 14 (19.4%) | p = 0.035 |

| No (n = 271) | 230 (84.9%) | 5 (1.8%) | 36 (13.3%) |

Summary of adequate ET tube size (per age) according to subgroup. Endotracheal tube size copied from the original patient protocol. Adequate ET tube size is indicated by the Microcuff tube manufacturer. Outside a 15% tolerance, ET tube size is judged as inadequate. All ET tubes contained a cuff

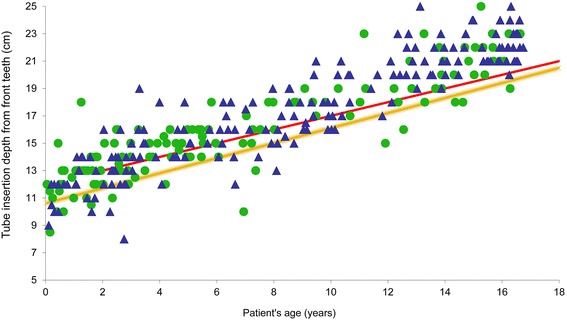

Correlation of ET tube depth of insertion with patient’s age in all missions

Orotracheal tube depth of insertion was noted in 303 (73%) of all protocols. Figure 2 shows depth of insertion of ET tubes for primary and secondary mission in relation to a calculated depth of insertion according to Weiss et al. [31] and to a standard formula for oral ET tube insertion for children over 2 years of age [35]. With regard to the depth of ETI calculated by the Weiss formula including a 15% tolerance, only six of 303 (2%) ET tubes were shallower, whereas 118 of 303 (38.9%) ET tubes were deeper than calculated. None of the ET tubes in this study had been placed too deep intentionally for reasons of lung separation or one lung ventilation.

Fig. 2.

Tube depth of insertion (cm) for patient age (years). Filled triangle = primary mission; filled dot = secondary mission; yellow line = depth of insertion (10.612 + age [years] × 0.5493 in cm) according to Weiss et al. [31] Red line = depth of insertion according to formula (12 + [years] × 0.5 in cm) [35]

Discussion

This study investigated the incidence of difficult airways and the ETI success rate in primary missions and the choice of ET tube size and depth of insertion in all paediatric patients treated by a Swiss HEMS. The main findings were that during primary missions ETI was successful with the first attempt in 95.3%. Apart from that, ET tube sizes were chosen inadequately large in 14.6% of all cases, especially in the age group new born to 1 year, in which 57.6% of the ET tubes were chosen inadequately large for age. Depth of ET tube insertion was frequently and considerably deeper than calculated by formulae.

Endotracheal intubation success rate and incidence of difficult airway management

Compared to Hansen et al. [13], our analysis showed a higher rate of successful ETI (> 95% at first attempt versus 81% in total). Our success rate is comparable to in-hospital paediatric emergency ETI [34]. Published studies concerning difficult airway management in adult patients, presented data similar to the findings in the current study regarding the incidence of a difficult airway and ETI. In a clinical setting, unexpected poor glottis visualisation during direct laryngoscopy was encountered in 1–9 % of intubation attempts, difficulties during laryngoscopy occurred in 5.8% and difficult ETI in up to 3.2% of all patients [10, 36, 37]. All patients in our study had a documented carbon dioxide measurement with any advanced airway device (supraglottic and ET tube) in place compared to less than 50% documented carbon dioxide measurement in the Hansen analysis [13]. We hypothesize that the difference in proficiency level (paramedic versus specially trained physician) and the mandatory use of capnometry to distinctively confirm ETI account for the discrepancy in terms of successful ETI.

In our HEMS organisation, supraglottic airway devices were only used as rescue devices in the case of inability to perform ETI. Questions concerning patient’s outcome after pre-hospital ETI versus supraglottic airways are still unanswered [38, 39].

Correlation of endotracheal tube size with patient’s age

Choosing the adequate ET tube size can be difficult in emergency situations as formulae and the manufacturer recommendations are age dependant. Taking into account that this tube size recommendation for Microcuff tubes is correct in 97.4% of the cases (or infrequently needs an exchange with a smaller ET tube) [23], an incidence of 14.6% larger ET tubes than recommended even after adding a 15% tolerance predisposes a large group of patients to a risk of airway trauma.

During or after cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ET tube size was chosen inadequately in a higher (scantly not significant) proportion of cases. This may be due to a higher stress level or a shortage of time for the choice of correctly sized equipment. Interestingly, there was no difference between primary and secondary missions concerning adequate ET tube sizes. This may be a sign of a generally limited experience in advanced paediatric emergency airway management, especially in very young children.

Correlation of endotracheal depth of insertion with patient’s age

Regarding the noted ET tube depth of insertion, most tracheas where intubated deeper than predicted by known age-based formulae, even after the addition of a 15% tolerance [31, 35, 40]. Keeping in mind that patients might be moved substantially during transport, incorrect depth of insertion predisposes to accidental bronchial intubation due to head inclination [28–30]. Only the placement of the depth marking of the correct Microcuff ET tube (Kimberly-Clark Health Care Europe, Zaventem, Belgium) for age between the vocal cords was accurate for all paediatric patients in contrast to age-based calculations [31, 33]. Hence a (supplemental) laryngoscopic inspection may be necessary to reposition the ET tube prior to transport.

Limitations of our study are its retrospective design, relatively low patient numbers in comparison to Hansen et al. [13] and the lack of visualisation of the ET tube depth of insertion by x-ray, fibre-optic inspection or ultrasound. Our original HEMS data was not standardised in terms of recording adverse events related to airway management, so the incidence would have been largely underestimated with limited scientific value and therefore this data was not presented and discussed in this study.

Nevertheless this is the largest analysis of pre-hospital paediatric emergency airway managements performed by designated pre-hospital emergency physicians only. Future prospective trials need be planned to assess adverse events and outcome after ETI of paediatric emergency patients by the hand of the experienced physician.

Conclusion

Difficult airway management, including cannot intubate and cannot ventilate situations during pre-hospital paediatric emergency treatment was rare. In contrast, the success rate of ETI at the first attempt was very high. High numbers of inadequate ET tube size and deep placement according to patient age require further analysis. Practical algorithms need to be found to prevent inaccurate treatment. Capnography must be used during advanced airway management.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mario Tissi of the Swiss Air-Ambulance for his continuing support in data delivery and database management.

Footnotes

Competing interest

The study was not funded. Abstract data was presented at the poster session of the ESA congress in Berlin 2015.

Donat R. Spahn has the following conflicts of interest: Donat R. Spahn’s academic department is receiving grant support from the Swiss National Science Foundation, Berne, Switzerland; the Ministry of Health (Gesundheitsdirektion) of the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland, for Highly Specialized Medicine; the Swiss Society of Anesthesiology and Reanimation (SGAR), Berne, Switzerland; the Swiss Foundation for Anesthesia Research, Zurich, Switzerland; the Bundesprogramm Chancengleichheit, Berne, Switzerland; CSL Behring, Berne, Switzerland; and Vifor SA, Villars-sur-Glâne, Switzerland.

Donat R. Spahn was the chairman of the ABC Faculty and is the co-chairman of the ABC-Trauma Faculty, which both are managed by Physicians World Europe GmbH, Mannheim, Germany, and sponsored by unrestricted educational grants from Novo Nordisk Health Care AG, Zurich, Switzerland; CSL Behring GmbH, Marburg, Germany; and LFB Biomédicaments, Courta- boeuf Cedex, France.

In the past 5 years, Donat R. Spahn has received honoraria or travel support for consulting or lecturing from the following companies: Abbott AG, Baar, Switzerland; AMGEN GmbH, Munich, Germany; AstraZeneca AG, Zug, Switzerland; Bayer (Schweiz) AG, Zürich, Switzerland; Baxter AG, Volketswil, Switzerland; Baxter S.p.A., Roma, Italy; B. Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany; Boehringer Ingelheim (Schweiz) GmbH, Basel, Switzerland; Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Rueil-Malmaison Cedex, France, and Baar, Switzerland; CSL Behring GmbH, Hattersheim am Main, Germany, and Berne, Switzerland; Cu- racyte AG, Munich, Germany; Ethicon Biosurgery, Sommerville, NJ, USA; Fresenius SE, Bad Homburg v.d.H., Germany; Galenica AG, Bern, Switzerland (including Vifor SA, Villars-sur-Glâne, Switzerland); GlaxoSmithKline GmbH & Co. KG, Hamburg, Germany; Janssen-Cilag AG, Baar, Switzerland; Janssen- Cilag EMEA, Beerse, Belgium; Merck Sharp & Dohme AG, Luzern, Switzerland; Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsvärd, Denmark; Octapharma AG, Lachen, Switzerland; Organon AG, Pfäffikon/SZ, Switzerland; Oxygen Biotherapeutics, Costa Mesa, CA, USA; Photonics Healthcare GmbH, Munich, Germany; ratiopharm Arzneimittel Vertriebs-GmbH, Vienna, Austria; Roche Diagnostics International Ltd, Reinach, Switzerland; Roche Pharma (Schweiz) AG, Reinach, Switzerland; Schering-Plough International, Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA; Tem International GmbH, Munich, Germany; Verum Diagnostica GmbH, Munich, Germany; Vifor Pharma Deutschland GmbH, Munich, Germany; Vifor Pharma Österreich GmbH, Vienna, Austria; and Vifor (International) AG, St. Gallen, Switzerland.

Authors’ contributions

ARS and LU contributed equally to this work. PS and RA conceived the idea for the study. BS performed the statistical analysis. LU collected the data. ARS, LU and PS analysed the data. All authors reviewed the article and approved the final version. PS coordinated and supervised data collections. DRS and RA contributed to the interpretation of the study results. ARS, LU and PS wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final article and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. PS takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

References

- 1.Sands SA, Edwards BA, Kelly VJ, Davidson MR, Wilkinson MH, Berger PJ. A model analysis of arterial oxygen desaturation during apnea in preterm infants. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardman JG, Wills JS. The development of hypoxaemia during apnoea in children: a computational modelling investigation. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:564–70. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt AR, Weiss M, Engelhardt T. The paediatric airway: basic principles and current developments. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2014;31:293–9. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz SH, Falk JL. Misplaced endotracheal tubes by paramedics in an urban emergency medical services system. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:32–7. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.112098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lackner CK, Reith MW, Ruppert M, Netzsch C, Widmann JH, Hofmann-Kiefer K, et al. Prähospitale Intubation und Verifizierung der endotrachealen Tubuslage. Notfall Rettungsmed. 2002;5:430–40. doi: 10.1007/s10049-002-0487-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timmermann A, Russo SG, Eich C, Roessler M, Braun U, Rosenblatt WH, et al. The out-of-hospital esophageal and endobronchial intubations performed by emergency physicians. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:619–23. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000253523.80050.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein P, Albrecht R, Spahn DR. Multiple trauma, resuscitation, and 15 minutes of esophageal intubation: survival without neurologic deficit. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:950.e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamiutsuri K, Okutani R, Kozawa S. Analysis of prehospital endotracheal intubation performed by emergency physicians: retrospective survey of a single emergency medical center in Japan. J Anesth. 2013;27:374–9. doi: 10.1007/s00540-012-1528-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fogg T, Annesley N, Hitos K, Vassiliadis J. Prospective observational study of the practice of endotracheal intubation in the emergency department of a tertiary hospital in Sydney, Australia. Emerg Med Australas. 2012;24:617–24. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thoeni N, Piegeler T, Brueesch M, Sulser S, Haas T, Mueller SM, et al. Incidence of difficult airway situations during prehospital airway management by emergency physicians—a retrospective analysis of 692 consecutive patients. Resuscitation. 2015;90:42–5. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breckwoldt J, Klemstein S, Brunne B, Schnitzer L, Mochmann H-C, Arntz H-R. Difficult prehospital endotracheal intubation - predisposing factors in a physician based EMS. Resuscitation. 2011;82:1519–24. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gausche M, Lewis RJ, Stratton SJ, Haynes BE, Gunter CS, Goodrich SM, et al. Effect of out-of-hospital pediatric endotracheal intubation on survival and neurological outcome: a controlled clinical trial. JAMA. 2000;283:783–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.6.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen M, Lambert W, Guise J-M, Warden CR, Mann NC, Wang H. Out-of-hospital pediatric airway management in the United States. Resuscitation. 2015;90:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerritse BM, Draaisma JMT, Schalkwijk A, van Grunsven PM, Scheffer GJ. Should EMS-paramedics perform paediatric tracheal intubation in the field? Resuscitation. 2008;79:225–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falck AJ, Escobedo MB, Baillargeon JG, Villard LG, Gunkel JH. Proficiency of pediatric residents in performing neonatal endotracheal intubation. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1242–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sagarin MJ, Chiang V, Sakles JC, Barton ED, Wolfe RE, Vissers RJ, et al. Rapid sequence intubation for pediatric emergency airway management. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:417–23. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200212000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cormack RS, Lehane J. Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 1984;39:1105–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1984.tb08932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timmermann A, Eich C, Russo SG, Natge U, Bräuer A, Rosenblatt WH, et al. Prehospital airway management: a prospective evaluation of anaesthesia trained emergency physicians. Resuscitation. 2006;70:179–85. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lockey D, Crewdson K, Weaver A, Davies G. Observational study of the success rates of intubation and failed intubation airway rescue techniques in 7256 attempted intubations of trauma patients by pre-hospital physicians. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:220–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orf J, Thomas SH, Ahmed W, Wiebe L, Chamberlin P, Wedel SK, et al. Appropriateness of endotracheal tube size and insertion depth in children undergoing air medical transport. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2000;16:321–7. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200010000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mostafa SM. Variation in subglottic size in children. Proc R Soc Med. 1976;69:793–5. doi: 10.1177/003591577606901101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss M, Dullenkopf A, Fischer JE, Keller C, Gerber AC. European Paediatric Endotracheal Intubation Study Group. Prospective randomized controlled multi-centre trial of cuffed or uncuffed endotracheal tubes in small children. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:867–73. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salgo B, Schmitz A, Henze G, Stutz K, Dullenkopf A, Neff S, et al. Evaluation of a new recommendation for improved cuffed tracheal tube size selection in infants and small children. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:557–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dullenkopf A, Gerber AC, Weiss M. Fit and seal characteristics of a new paediatric tracheal tube with high volume-low pressure polyurethane cuff. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49:232–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss M, Dullenkopf A, Bottcher S, Schmitz A, Stutz K, Gysin C, et al. Clinical evaluation of cuff and tube tip position in a newly designed paediatric preformed oral cuffed tracheal tube. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:695–700. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weiss M, Gerber AC. Safe use of cuffed tracheal tubes in children. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 2012;47:232–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1310411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dillier CM, Trachsel D, Baulig W, Gysin C, Gerber AC, Weiss M. Laryngeal damage due to an unexpectedly large and inappropriately designed cuffed pediatric tracheal tube in a 13-month-old child. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:72–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03018551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss M, Knirsch W, Kretschmar O, Dullenkopf A, Tomaske M, Balmer C, et al. Tracheal tube-tip displacement in children during head-neck movement--a radiological assessment. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96:486–91. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jordi Ritz EM, Von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Keller K, Frei FJ, Erb TO. The impact of head position on the cuff and tube tip position of preformed oral tracheal tubes in young children. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:604–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin-Hee K, Ro Y-J, Seong-Won M, Chong-Soo K, Seong-Deok K, Lee JH, et al. Elongation of the trachea during neck extension in children: implications of the safety of endotracheal tubes. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:974–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000169330.92707.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss M, Gerber AC, Dullenkopf A. Appropriate placement of intubation depth marks in a new cuffed paediatric tracheal tube. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:80–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phipps LM, Thomas NJ, Gilmore RK, Raymond JA, Bittner TR, Orr RA, et al. Prospective assessment of guidelines for determining appropriate depth of endotracheal tube placement in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:519–22. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000165802.32383.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kemper M, Dullenkopf A, Schmidt AR, Gerber A, Weiss M. Nasotracheal intubation depth in paediatric patients. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:840–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neuhaus D, Schmitz A, Gerber A, Weiss M. Controlled rapid sequence induction and intubation - an analysis of 1001 children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23:734–40. doi: 10.1111/pan.12213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hatch DJ. Paediatric anaesthetic equipment. Br J Anaesth. 1985;57:672–84. doi: 10.1093/bja/57.7.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shiga T, Wajima Z, Inoue T, Sakamoto A. Predicting difficult intubation in apparently normal patients: a meta-analysis of bedside screening test performance. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:429–37. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200508000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Combes X, Le Roux B, Suen P, Dumerat M, Motamed C, Sauvat S, et al. Unanticipated difficult airway in anesthetized patients: prospective validation of a management algorithm. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:1146–50. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200405000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bosch J, de Nooij J, de Visser M, Cannegieter SC, Terpstra NJ, Heringhaus C, et al. Prehospital use in emergency patients of a laryngeal mask airway by ambulance paramedics is a safe and effective alternative for endotracheal intubation. Emerg Med J. 2014;31:750–3. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-202283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schalk R, Seeger FH, Mutlak H, Schweigkofler U, Zacharowski K, Peter N, et al. Complications associated with the prehospital use of laryngeal tubes-A systematic analysis of risk factors and strategies for prevention. Resuscitation. 2014;85:1629–32. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunyady AI, Pieters B, Johnston TA, Jonmarker C. Front teeth-to-carina distance in children undergoing cardiac catheterization. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:1004–8. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181730288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]