Abstract

Background:

Due to the enormous migration as the result of war and disasters during the last decades, health systems in Europe are faced with various cultural traditions and both healthcare systems and healthcare professionals are challenged by human rights and values. In order to minimize difficulties in providing healthcare services to patients with different cultural backgrounds, cultural competence healthcare professionals are needed.

Material and Methods:

Four focus group interviews, were conducted with Kurdish immigrants in Scandinavian countries (N=26). The majority were males (n=18) aged between 33-61 years (M= 51.6 years) and a few were (n=8) females aged 41-63 years (M=50.7 years). The data were analyzed by using qualitative content analysis method.

Results:

According to the study results participants experienced that diversities both in culture and healthcare routines create a number of difficulties regarding contact with healthcare services. Though culture related aspects influenced the process of all contact with health care services, the obstacles were more obvious in the case of psychological issues. The results of the study showed that cultural diversities were an obvious reason for immigrants’ attitudes regarding healthcare services in resettlement countries.

Conclusion:

The results of the study revealed a number of difficulties beyond linguistic problems regarding immigrants’ contact with healthcare services in Scandinavian countries. Problems were rooted both in diversities in healthcare services and cultural aspects. Immigrants’ views of healthcare systems and healthcare professionals’ approach in providing healthcare were some of the problems mentioned.

Keywords: Health-care, language, immigrant patients, experiences, qualitative research

1. INTRODUCTION

Due to the enormous migration as the result of war and disasters during the last decades, health systems in Europe are faced with various cultural traditions and both healthcare systems and healthcare professionals are challenged by human rights and values (1). In order to minimize difficulties in providing healthcare services to patients with different cultural backgrounds, healthcare professionals need cultural competence (2). In this way health care professional cultural competence remains an important factor as part of the important strategy to address health inequities. In order to overcome this problem, it has been suggested that health care professional education should be improved to meet difficulties in providing health care to patients with cultural diversities (3-5). A combination of a good relationship and satisfactory communication between healthcare professionals and patients with immigrant backgrounds may have its foundation in acculturation orientation, which has a significant impact on the quality of healthcare, health behaviors and the quality of life of the patients with immigrant backgrounds (6).

In the case of acculturation, a satisfactory social relationship between immigrants and the native population is crucial (7). A previous study indicated that there are obvious obstacles to real and effective social interaction between immigrants and the native population in resettlement countries. Immigrants’ difficulties in finding jobs in resettlement countries is an obvious example of an obstacle in social interaction and acculturation (8). Not only are culture, health literacy and diversity in language obstacles to immigrant patients adaption to the health care system in resettlement countries, but also the lack of adequate information for immigrants has been mentioned (9). Health care providers’ attitudes, satisfaction and communication have a significant impact on equal health care in multicultural societies (10). Due to barriers to health care access and efficiency, patients with a migrant background, have a higher prevalence of some chronic diseases than the majority population (11). Knowledge about attitudes towards health care in different cultures and adapting health care services to multicultural issues is essential to providing equal health care to all inhabitants in multicultural societies (12, 13).

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

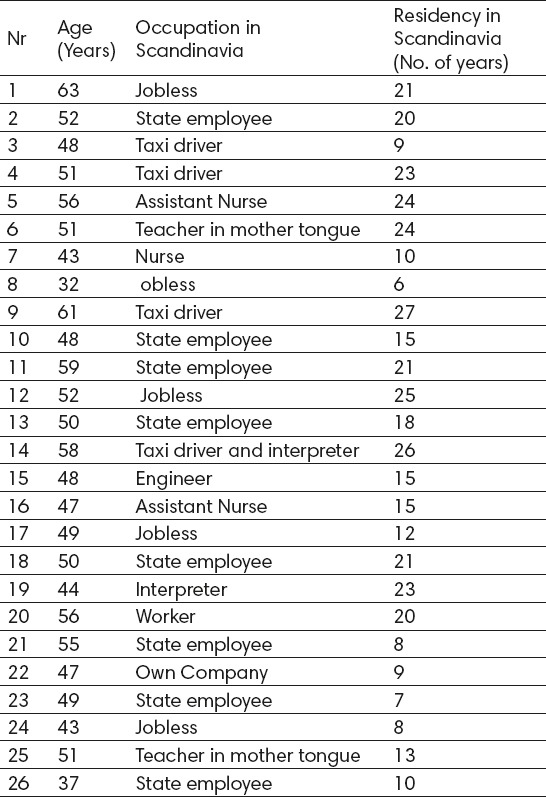

Of the forty-nine persons who were invited to participate in the study, thirty-two initially agreed to participate and eight of the participants declined participation for practical reasons. Of those who responded positively, a total of 26 persons participated in the interview. The majority were males (n=18) aged between 33-61 years (M= 51.6 years) and a few were (n=8) females aged 41-63 years (M=50.7 years) who had lived in Sweden between 16 and 40 years (Table 1). All contacts with the informants were arranged through Kurdish culture centers in Scandinavian countries. Information concerning the aim of the study was sent to participants by cultural associations via electronic post in their mother tongue. The same information was provided once again in print and explained orally before the interview started.

Table 1.

Background data of the study group (n=26)

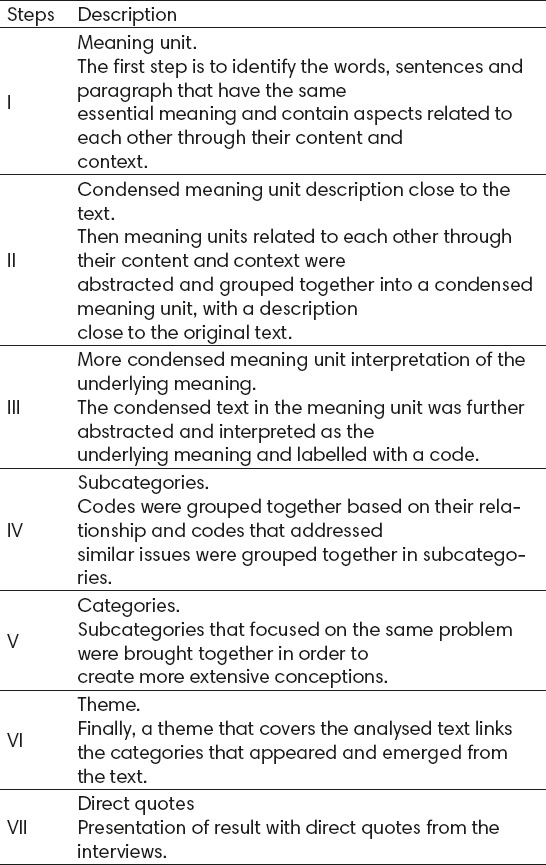

Four focus group interviews, based on the guidelines for this method (14) were conducted with participants between October 2014 and June 2015. The discussion began with general open-ended questions, following an interview guide for the qualitative research method (15). The main question was: “Could you please describe your experiences regarding healthcare services in your resettlement country compared with your original country?” In the course of the discussion deepening of the content, clarification and consideration were achieved by means of more target questions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Illustration of the analysis process in various stages

The interviews were in groups; the groups varied between four and seven persons and were held in the Kurdish culture centers in the respective countries. The interviews were carried out in the participant’s mother tongue. The interviews lasted between 95 and 115 minutes and were recorded digitally, and transcribed verbatim. A qualitative content analysis method (14) was used for analysis and interpretation of the collected data. The transcripts were read carefully in order to identify the informants’ experiences and conceptions.

Then the analysis proceeded by extracting meaning units consisting of one or several words, sentences, or paragraphs that contained aspects related to each other, addressing a specific topic, throughout the collected data. Meaning units that related to each other through their content and context were abstracted and grouped together in order to transfer them into a condensed meaning unit. The next step was to condense the text into a more abstracted issue and it was labeled with a relevant code. Then codes that addressed similar issues were grouped together, with the intention of identifying subcategories. Subcategories that focused on the same problem were brought together, in order to create more extensive conceptions, which addressed an obvious issue (14). The last step was the presentation of the results with direct quotations from the interviews (Table 2)

3. RESULTS

The analysis of the collected data in the study resulted in two main categories and four subcategories. The first category dealt with physiological care and the second was about psychological care (Table 2).

Physiological care

Cultural aspect

The result of the study showed that there is an obvious difference in interpretation of the concept of physiological disease in the participants’ resettlement countries compared with their countries of origin. According to the participants’ experiences, this thinking was the main reason behind the participants’ attitude towards seeking psychological care, despite their needs. Based on the results of the study, in the countries that participants came from, very often psychological problems are described by physiological symptoms since psychological diseases are considered to be a negative event and a disgrace for the patient as well as all the family. “If someone seeks a doctor for psychological problems in our country it means that she/he is mad and socially disabled, which is a major disgrace in our culture”, one participant stated.

“It is a major disgrace to have a psychotic person in your family. When I was a child our neighbors got into a conflict with another family. I remember when she blamed him because of his grandfather’s psychological disease”.

According to the results, understanding of psychological diseases has a significant impact on immigrants’ attitude regarding their wish to seek psychological help. One of the participants stated that only those who are completely mad and dangerous and may cause problems for themselves others should seek such help.

“I wonder why one must seek psychological help for every unpleasant event that may affect one’s life. In Sweden when after the Estonia ship disaster all families that lost a friend or relative sought psychological treatment, it was quite strange for me”.

Another participant confirmed his statement as follows:

“If we sought psychological help for every disaster all inhabitants in our country would have to undergo psychological treatment, ha…ha…”

Gender perspective

The results of the present study revealed that there are obvious differences between men and women in both the original and resettlement countries. According to the participants’ experiences, if a man and a woman in the same situation and with the same background data come to Europe as refugees, it is easier for the woman to make social contacts than for the man. The results showed 5% (N=8) of women that participated in the study sought psychological help but 20% (N=18) men who participated in the study sought the same help. “Women’s openness and ability to learn languages are mentioned as factors contributing to the fact that they make better contact with people in their new societies as well as contact with healthcare” said one participant in the study.

Based on the results, it is seen to be more disastrous and disgraceful for the family if a female member of the family is affected by a psychological disorder, because it may develop into a greater disgrace for the family.

“When I was in Iran, we had a neighbor whose daughter had a kind of psychological disease. Every day when they went to work they locked all the doors and their daughter could not come out until they came back from work. One day I asked her mother why their daughter had to be in a locked room all day until one of the family come back from work. She said they were afraid that a strange man take may have a relationship with her and do something, then it would be a double disgrace for the family”.

The results indicated that the level of education in the home country has a significant impact on the immigrants’ attitude to seeking both physical and psychological health care in the resettlement countries. In our culture a man should be patient, never cry, and not seek help for every event that happens to him. Another participant continued as follow:

“In our culture, if a man cries and is impatient, we blame him saying do not cry, you are a man not a woman”.

Physiological care

Different healthcare routines

The majority of participants expressed that healthcare routines in settlement countries are many times more complicated compared to their home countries. They mentioned that it is a long process and takes quite a long time to visit a specialist doctor. They stated that they could visit a specialist doctor when they wanted, because there are many private clinics which are available at all times.

“Sometimes it takes so long time to visit a specialist doctor that when we get information that we have an appointment to visit a specialist we have already forgotten what the problem was that we needed help with”

The results showed that some of the participants did not seek healthcare for cases of simple diseases until they had developed to advanced stages. One participant claimed that they never got adequate help when they sought it for simple diseases. Another participant added that it is not necessary to seek healthcare for every kind of disease, we have an expression that says “As long as we are able to eat we are not considered ill”.

A participant stated that when they seek healthcare at the healthcare center the process often begins with a consultation with a nurse, which is mentioned as strange for the participant.

“In our country a nurse never decides if a patient needs to visit a doctor or not, I wonder how a nurse could make such a decision”.

Additional problems mentioned by participants regarding seeking healthcare were difficulties in contacting healthcare nurses in order to make an appointment.

“If we call them it is difficult to get through to the nurses and if we go to the healthcare center we must sit there many hours”.

Different views on medication

According to the obtained results, a number of the participants criticized general practitioners regarding management, medication and treatment of diseases. They expressed that general practitioners often act as an adviser rather than a true doctor.

“If one leaves a health care center after visiting a general practitioner without medicine it seems he/she has visited a religious guide rather than a general practitioner” said one of the participants in the study.

Another participant added that once he visited a general practitioner with a severe headache and high fever, but instead of giving medication he advised him to stay at home and drink water.

“I told him I am here for medicine and treatment not for advice, my mother has already given me such advice, I am not here to get just advice”.

Participants not only discussed the issue of medication but also which kinds of medication are best. One of the participants declared that he often needs to go to the healthcare center because of diseases that have affected him for many years. He stated that he is always given tablets as treatment and has never been given an injection. “Just like eating lime or chalk, ha…ha…ha…” said another participant? It appeared that this issue was of interest for many of the participants. The reason why an injection is considered the best alternative as treatment of diseases was expressed as follows by another participant:

“Injections act correctly and faster than tablets, they go direct into the blood circulation, but a tablet’s effect disappears in the stomach. Also tablets may destroy our stomach and cause other diseases”.

4. DISCUSSION

Analysis of the collected data concerning immigrants’ experiences of the quality of healthcare services requires a qualitative analysis method. For this purpose we used a content analyses method (14) as a method suitable for analyses of the data collected in our study. Furthermore, a cross-cultural study often contains cultural expressions, which must be interpreted rather than translated. This method is suitable for interpretation of expressions as well as both manifest and latent aspects in the text. Based on this method, the primary step of the analysis should focus on the content and describe the visible elements, and in the second step, analysis of what the text is about involves an interpretation of the underlying meaning (14). The study results revealed that the participants experienced that diversities both in culture and healthcare routines create a number of difficulties regarding contact with healthcare services. Though culture related aspects influenced the process of all contact with health care services, the obstacles were more obvious in the case of psychological issues. Although the biological origin of disease is constant between different cultures, how health and illness are expressed and understanding them vary from culture to culture, as well as from society to society (16). Immigrants’ attitudes, beliefs and understanding of diseases have a significant impact on their decisions to seek healthcare assistance (17).

The results of the study showed that cultural diversities were an obvious reason for immigrants’ attitudes regarding healthcare services in resettlement countries. Previous studies have also shown that in order to provide ethnically true healthcare to immigrant patients, nurses and other healthcare professionals must have basic knowledge and experience of culture-specific syndromes, as well as idioms of distress, beliefs and practice issues that may be present among the patient groups with cultural diversities that they meet in their daily work (18, 19). In terms of healthcare equality and attitudes toward healthcare, the gender perspective is also of interest (20). Apart from social and cultural dimensions, such as ethnicity, social class and age, gender related aspects occur at the same time in providing healthcare to immigrant patients (21). Our study revealed diversity between male and female participants in immigrants’ attitudes regarding seeking psychological healthcare. Openness and the ability to learn languages were mentioned as influential factors in this issue. Our results are in line with a pilot study in the USA that indicated that women are more likely than men to recognize the need for psychological help (22, 23).

Diversities in health care systems and attitudes towards medication were additional aspects that were discussed in the group discussions. This diversity, which could be considered as a combination of culture and differences in healthcare systems and practical routines between home countries and resettlement countries, influences healthcare services for immigrant patients. Adaption of the healthcare system to the multicultural society is needed, to provide healthcare to all our patients on the same level (13). In order to provide healthcare services to immigrants, health care professionals need a better and deeper understanding of immigrants’ needs, in view of the immigrants’ cultural background and simple healthcare routines (24). It is importance that the healthcare system is adjusted to the needs of all inhabitants, both the native population and immigrants (24). Immigrants’ view of medication was discussed in the group discussions. Regarding treatment of diseases, some of the participants expressed the wish for medication when they visited their general practitioner, particularly in the form of injections. Previous studies showed that culture related factors have a significant impact on medication (25).

Potential sources of bias

As the investigator belongs to the same ethnic group as the participants in this study, this may be considered a risk factor for impartiality in the planning, execution and analysis of the collected data, because of pre-understanding (26). Though some bias as a result of the investigator’s background and his pre-understanding of the research subject cannot be ruled out, the degree of openness, depth and confidence obtained throughout the interview process probably out-performed potential biases that could not be totally ruled out. Furthermore, bias in the research process was hopefully limited by the investigator’s consciousness of the limitations of qualitative methods, and knowledge about the impact of the ‘‘life-world paradigm’’ concerning pre-understanding. Moreover, the researcher tried to pay attention to the balance between closeness and distance in the discussions, as recommended for data collection in qualitative research methods (27).

5. CONCLUSION

The results of the study revealed a number of difficulties beyond linguistic problems regarding immigrants’ contact with healthcare services in Scandinavian countries. Problems were rooted both in diversities in healthcare services and cultural aspects. Immigrants’ views of healthcare systems and healthcare professionals’ approach in providing healthcare were some of the problems mentioned. Diversity in immigrants’ views of medication compared with their home countries was another issue highlighted by participants in this study.

Footnotes

• Author’s contribution: All authors contributed in all phases of preparing this article. Final proof reading was made by first author.

• Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbing HD. The one who chooses a country chooses its laws: health law and multicultural societies. Med Law. 2010;29(2):141–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belintxon M, López de Dicastillo O. The challenges of health promotion in a multicultural society: a narrative review. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2014;37(3):401–9. doi: 10.4321/s1137-66272014000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horvat L, Horey D, Romios P, Kis-Rigo J. Cultural competence education for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009405.pub2. doi:10.1002/14651858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kools S, Chimwaza A, Macha S. Cultural humility and working with marginalized populations in developing countries. Glob Health Promot. 2015;22(1):52–9. doi: 10.1177/1757975914528728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGee P, Johnson MR. Developing cultural competence in palliative care. Br J Community Nurs. 2014;19(1):91–3. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2014.19.2.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whittal A, Rosenberg E. Effects of individual immigrant attitudes and host culture attitudes on doctor-immigrant patient relationships and communication in Canada. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14:108. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0250-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fatahi N. Økland ØDifficulties and Possibilities in Kurdish Refugees'Social Relationship and its Impact on their Psychosocial Well- Being. J Family Med Community Health. 2015;2(3):1035–61. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fatahi N. The Impact of the Migration on Psychosocial Well-Being: A Study of Kurdish Refugees in Resettlement Country. J Community Med Health Educ. 2014;4(2):273–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Festini F, Focardi S, Bisogni S, Mannini C, Neri S. Providing transcultural to children and parents: an exploratory study from Italy. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2009;4(2):220–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanchetta MS, Poureslami IM. Health literacy within the reality of immigrants' culture and language. Can J Public Health. 2006;97(2):26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brzoska P, Razum O. Prevention among migrants - problems in health care provision and suggested solutions illustrated for the field of medical rehabilitation. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2014;189(38):5–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1387238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rittle C. Multicultural Nursing: Providing Better Employee Care. Workplace Health Saf. 2015;21 doi: 10.1177/2165079915590503. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krupic F, Krupic R, Jasarevic M, Sadic S, Fatahi N. Being Immigrant in their Own Country: Experiences of Bosnians Immigrants in Contact with Health Care System in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Mater Sociomed. 2015;27(1):4–9. doi: 10.5455/msm.2014.27.4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ today. 2004;14(4):433–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kvale S. Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun. (The qualitative Research Interview) Sweden (In Swedish): Studentliteratur, Lund; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bishop GD. Health and illness: Mental representations in different cultures. International Encyclopaedia of the Social & Behavioural Sciences. Singapore: National University of Singapore; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crawford J, Ahmad F, Beaton D, Bierman AS. Cancer screening behaviours among South Asian immigrants in the UK, US and Canada: a scoping study. Health Soc Care Community. 2015;27 doi: 10.1111/hsc.12208. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellis HA. Obeah-illness versus psychiatric entities among jamaican immigrants: cultural and clinical perspectives for psychiatric mental health professionals. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29(2):83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higginbottom GM, et al. Immigrant women's experiences of maternity-care services in Canada: a systematic review using a narrative synthesis. Syst Rev. 2015;11(4):27–30. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fatahi N. Cross-Cultural encounters through interpreter - Experiences of patients, interpreters and healthcare professionals. Avhandling. Göteborgs universtitet. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klig J. On communication, humanism, and the brief encounter. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2005;17(3):49–50. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000164600.98506.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thikeo M, Florin P, Ng C. Help Seeking Attitudes Among Cambodian and Laotian Refugees: Implications for Public Mental Health Approaches. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;12 doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0171-7. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorcas E, et al. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. SPINE. 2000;25(24):3186–91. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hultsjö S, Hjelm K. Immigrants in emergency care: Swedish health care staff's experiences. Int Nurs Rev. 2005;52(4):276–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2005.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.K M, Cinnirella M. Beliefs about the Efficacy of Religious, Medical and Psychotherapeutic Interventions for Depression and Schizophrenia among Women from Different Cultural–Religious Groups in Great Britain. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1999 Dec;36(3):491–504. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nystrom M, Dahlberg K. Pre-understanding openness - a relationship without hope? Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;15(4):339–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2001.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahlberg K. Kvalitativa metoder för vardvetare. Qualitative methods in the nursing sciences. Lund: Studentlitteratur Publishing; 1996. [Google Scholar]