Abstract

Objective

Exposure to multiple traumatic events (polyvictimization) is a reliable predictor of deleterious health outcomes and risk behaviors in adolescence. The current study extends the literature on the prevalence and consequences of adolescent trauma exposure by (a) empirically identifying and characterizing trauma exposure profiles in a large, ethnically diverse, multi-site, clinical sample of adolescents, and (b) evaluating relations among identified profiles with demographic characteristics and clinical correlates.

Method

Data from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Core Data Set were used to identify and characterize victimization profiles using latent class analysis in a sample of 3,485 adolescents (ages 13–18, 63% female, 35.7% White, 23.2% Black/African American, 35.0% Hispanic/Latino). Multiple measures of psychological distress and risk behaviors were evaluated as covariates of trauma exposure classes.

Results

Five trauma exposure classes, or profiles, were identified. Four classes—representing approximately half the sample—were characterized by polyvictimization. Polyvictimization classes were differentiated on number of trauma types, whether emotional abuse occurred, and whether emotional abuse occurred over single or multiple developmental epochs. Unique relations with demographic characteristics and mental health outcomes were observed.

Discussion

Results suggest polyvictimization is not a unidimensional phenomenon but a diverse set of trauma exposure experiences with unique correlates among youth. Further research on prevention of polyvictimization and mechanisms linking chronic trauma exposure, gender, and ethnicity to negative outcomes is warranted.

Keywords: adolescence, polyvictimization, polytraumatization, complex trauma, trauma exposure, maltreatment, mental health

Exposure to potentially traumatic events (PTEs) is prevalent during adolescence (Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2013; Kilpatrick et al., 2003). Youth exposed to one PTE type are at elevated risk for experiencing multiple PTE types over time (Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, & Hamby, 2005). Epidemiologic studies suggest that polyvictimization (i.e., exposure to multiple PTEs regardless of source, repetitiveness, or chronicity) in adolescence is common (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007a; Ford, Elhai, Connor, & Freuh, 2010); 25% of youth report exposure to multiple types of direct victimization, over 10% report 5+ types, and 1.4% report exposure to 10+ types of violence annually (Finkelhor et al., 2011; Finkelhor et al., 2013). A study of adolescents in a clinical outpatient setting found 1 in 8 youth reported polyvictimization, with trauma taking place across multiple contexts (Alvarez-Lister, Pereda, Abad, Guilera, & Grevia, 2014). PTE types are often studied in isolation, which may mask important differences among youth exposed to complex, varied patterns of trauma (Kazdin, 2011). The purpose of this study was twofold: to identify patterns or profiles of PTE exposure—particularly with respect to polyvictimization—in a large sample of clinic-referred adolescents, and to evaluate relations between identified profiles and demographic characteristics and mental health outcomes.

Polyvictimization is associated with higher rates of mental health problems (Briere, Kaltman, & Green, 2008; Greeson et al., 2012; Finkelhor et al., 2007a,b; Ford et al., 2010; Macdonald et al., 2010), with repeated early exposure showing increased negative impact on functioning across multiple domains (Cook et al., 2005). The cumulative risk model posits that combinations of risk factors, including psychosocial adversities and PTEs, aggregate and interact to increase potential for negative outcomes (Sameroff, 2000). According to the related ‘risk factor caravan’ model, certain types of PTEs and stressors may be more likely than others to cluster or co-occur across one’s development, accumulating risk for a variety of negative consequences, including mental health problems (Layne, Briggs, & Courtois, 2014). These models provide a useful framework for considering why individuals experience particular combinations of PTEs and resultant mental health consequences across development. There is variability in how polyvictimization and the related constructs of polytraumatization and complex trauma are operationalized, however; many studies have used simple counts of PTE types to define the constructs. This approach treats polyvictimization as a unitary phenomenon and ignores different combinations of PTEs that may be more common among adolescents than others, or certain profiles that may be uniquely associated with specific clinical outcomes (Spinazzola et al., 2014). For instance, polyvictimization profiles marked by emotional or verbal abuse (Spinazolla et al., 2014), early childhood onset (Kaplow & Widom, 2007), and prolonged duration of trauma exposure (Manly, 2005) may be uniquely predictive of emotional distress. However, few studies have used analytic approaches that empirically identify polyvictimization based on trauma characteristics (type, duration, onset). In response, research is needed to elucidate the nature and correlates of polyvictimization profiles among adolescents and whether consideration of unique PTE profiles holds utility for clinical practice and research.

One approach to identifying trauma profiles empirically involves latent class analysis (LCA), a multivariate statistical method used to untangle complex data by identifying relatively homogeneous classes (i.e., profiles, subgroups) with similar characteristics. Ford et al. (2010) used LCA in a nationally representative community sample of adolescents and found six trauma profiles. Four of the profiles, comprising one-third of the sample, were characterized by polyvictimization, whereas the other two profiles included youth who primarily witnessed violence or experienced disasters or accidents. Moreover, polyvictimized youth experienced more adverse mental health outcomes, including being 2.2–5.6 times more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for PTSD and 3.4–16.2 times more likely to engage in drug use than youth who experienced one trauma type. The use of empirically derived trauma profiles (Ford et al., 2010) was innovative, and offered valuable insight into patterns of adolescent polyvictimization in the general population. Consideration of clinic-referred youth represents a logical extension of this work that carries important implications for healthcare providers working with adolescents.

Polyvictimization patterns and associations with psychological distress have not been examined in a large, diverse sample of clinically referred adolescents. Where it has been studied in clinical samples of adolescents, polyvictimization was globally associated with PTSD (Ford, Wasser, & Connor, 2011) and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology in outpatients (Alvarez-Lister et al., 2014) and externalizing behaviors in inpatients (Ford, Connor, & Hawke, 2009). Methodological limitations of these prior studies, including small sample size, simple counts of trauma types, or cluster analysis as opposed to latent class analysis (DiStefano & Kamphaus, 2006) have precluded identification of unique polyvictimization profiles or direct comparisons of polyvictimization between community and clinical samples. The ubiquitous and deleterious nature of polyvictimization, broadly defined, particularly during adolescence, highlights the need to better understand the heterogeneity and consequences of the phenomenon.

Another limitation of the polyvictimization literature is that PTE chronicity is inconsistently included in definitions or statistical models. Similar to psychopathology (Krueger & Markon, 2011), traumatic stress varies along several dimensions, including chronicity (Manly 2005). Whereas PTE exposure across multiple developmental stages predicts more severe symptoms (English, Graham, Litrownik, Everson, & Bangdiwala, 2005; Graham et al., 2010), chronicity of polyvictimization appears to be less influential in predicting outcomes than the number of PTE types experienced (e.g., Finkelhor et al., 2007b; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2010). LCA and cluster analysis have yet to incorporate PTE chronicity when investigating polyvictimization, however. This study examined whether adolescents experienced PTEs across multiple developmental stages (epochs) to determine if certain polyvictimization profiles were more highly associated with trauma exposure across epochs than others.

Finally, findings on whether race or ethnicity relate to polyvictimization have been mixed, with some research indicating that non-white ethnicity increases vulnerability to polyvictimization (Ford et al., 2010), whereas others found no such relation (Finkelhor et al., 2009). Discrepancies could be due to the use of different classification systems (e.g., LCA, cluster analysis, PTE counts) and operationalization of ethnicity (e.g., measurement of race versus ethnicity). Thus, this study examined whether racial group identification, along with other demographic characteristics (e.g., gender and primary residence/living arrangement), was associated with particular polyvictimization profiles. Understanding which youth are more vulnerable to distinct patterns of trauma within the cumulative risk model, and thus certain clinical outcomes, may lead to more targeted adolescent prevention and intervention programs.

This study had two key aims: (1) to identify and characterize the number and composition of latent polyvictimization classes in a large, ethnically diverse, multi-site, clinic-referred sample of adolescents using the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) Core Data Set (CDS), and (2) to evaluate associations between identified polyvictimization profiles and (a) demographic characteristics and (b) distress and impairment. Based on theoretical models positing multiple pathways and combinations of PTE exposure (e.g., Layne et al., 2014) and past research in community samples (e.g., Ford et al., 2010), we hypothesized multiple polyvictimization classes would be identified, and that polyvictimization overall would be more prevalent in a clinical sample than community samples. We anticipated that trauma types represented by the polyvictimization classes would correspond to pathways to adolescent polyvictimization described in prior research (i.e., community, school, and interpersonal violence associated with residing in dangerous neighborhoods; maltreatment and domestic violence associated with living in dangerous families; chronic exposure to impaired caregivers, maltreatment, and assault associated with having chaotic family environments) (Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, & Holt, 2009). Given the mixed results of previous studies exploratory analyses examined whether ethnicity and gender are related to particular patterns of PTE.

Regarding clinical outcomes, it was predicted that polyvictimization profiles involving higher numbers of PTEs and more severe forms of victimization would be associated with greater psychological distress (Finkelhor et al., 2011; Ford et al., 2010), consistent with the cumulative risk model (Samaroff, 2000). Further, consistent with past polyvictimization research (Cyr et al., 2013; Layne eta l., 2014), we predicted that polyvictimization profile(s) that included sexual victimization and/or emotional maltreatment would correspond to elevated levels of distress. Exploratory analyses examined whether other combinations of trauma across different developmental epochs were associated with different patterns of mental health problems.

Method

The present study used data from the NCTSN-CDS, a quality improvement initiative designed to standardize assessment procedures across NCTSN sites. The NCTSN-CDS was collected from 2004 to 2010 at 56 centers across the United States, including community-based organizations, hospitals, and universities providing youth mental health services (Briggs et al., 2012; Pynoos et al., 2008). The CDS includes core clinical and demographic characteristics, trauma history details, and treatment services information for 14,088 youth, aged birth to 21 years, who presented for assessment and treatment following PTE exposure. Procedures were approved by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the respective IRBs of all participating NCTSN sites. Trained staff obtained assent/consent from youth and their guardians and collected data as part of routine clinical care at intake.

Sample

The sample included youth aged 13–18 years (n=4,720), with 1+ confirmed trauma (n=3,754) and reported age(s) of exposure (n=3,485). The sample was racially/ethnically diverse and approximately 63% were female. This sample was randomly divided into two subsamples (n=1,743 and n=1,742) for exploratory and confirmatory analyses. Demographic characteristics are listed in Table 1 for the exploratory sample, which was the sample of primary emphasis here.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, Lifetime Number of Trauma Types, and Emotional and Behavioral Functioning (N=1,743)

| Variable | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 667 | (38.3%) |

| Female | 1,076 | (61.7%) |

| Race/Ethnicity (n = 1,680) | ||

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 571 | (34.0%) |

| Black/African American | 401 | (23.9%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 612 | (36.4%) |

| Other | 96 | (5.7%) |

| Primary Residence (n = 1,589) | ||

| Home (with parent(s)) | 1,004 | (63.2%) |

| Home (with relatives) | 208 | (13.1%) |

| Foster Care | 135 | (8.5%) |

| Residential treatment/Correctional facility | 152 | (9.6%) |

| Other | 90 | (5.7%) |

|

| ||

| Lifetime Number of Trauma Types | 4.0 | (2.5) |

|

| ||

| CBCL (n =1,180) | Clinical Range | |

| M (SD) | N (%) | |

| Externalizing Behavioral Problems | 62.7 (10.6) | 610 (51.7%) |

| Internalizing Behavioral Problems | 62.3 (11.0) | 577 (48.9%) |

| Total Behavioral Problems | 63.5 (10.1) | 670 (56.8%) |

| UCLA PTSD-RI (n = 1,521) | Clinical Range | |

| M (SD) | N (%) | |

| Re-experiencing Subscale | - | 1,117 (76.4%) |

| Avoidance Subscale | - | 783 (53.5%) |

| Hyperarousal Subscale | - | 1,145 (78.3%) |

| Overall Score | 26.7 (15.0) | 385 (25.3%) |

|

| ||

| Risk Behaviors | N | (%) |

|

| ||

| Alcohol/Substance Use | 392 | (22.5%) |

| Suicidality | 417 | (25.3%) |

| Self-injurious Behaviors | 278 | (16.9%) |

Measures

Trauma History Profile (THP)

The THP is a 20 item trauma screener derived from the UCLA PTSD-Reaction Index (UCLA PTSD-RI; Steinberg, Brymer, Decker, & Pynoos, 2004). The THP was used to gather data from multiple informants - child/adolescent, parents/caregivers, and other collaterals (e.g., caseworkers) and included a comprehensive list of trauma types: 1) sexual maltreatment/abuse (by a caregiver); 2) sexual assault/rape (not by a caregiver); 3) physical abuse/maltreatment (by a caregiver); 4) physical assault (not by a caregiver); 5) emotional abuse/psychological maltreatment (emotional abuse, verbal abuse, excessive demands, emotional neglect); 6) neglect; 7) domestic violence; 8) illness/medical trauma; 9) injury/ accident; 10) traumatic loss/separation/bereavement; 11) having an impaired caregiver (caretaker depression, other medical illness, alcohol/drug abuse); 12) extreme interpersonal violence (not reported elsewhere); 13) community violence (not reported elsewhere); and 14) school violence. The remaining THP variables (e.g., exposure to war, natural disasters, kidnapping, forced displacement) occurred in less than 5% of the sample and were not included in the analysis.

Standard, detailed definitions, modeled after the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) Glossary (NCANDS, 2000) were provided to clinical staff before intake administration. Staff participated in mandatory trainings and ongoing quality assurance through the National Center for Child Traumatic Stress to ensure data integrity. For each item, clinicians indicated whether a trauma was thought to have occurred (Yes/No), and if so, whether the event was suspected or confirmed in the intake evaluation process (e.g., child interview, information from caregivers, Child Protective Service records). Only confirmed—not suspected—trauma types were used in the analyses here to minimize discrepancies in information reported by multiple respondents and from multiple sources.

For each trauma endorsed, clinicians provided additional information about the experience (e.g., age of exposure, duration, frequency, etc). The reported age of exposure was used to classify the trauma as occurring during one of three developmental epochs: 0–5 years of age, 6–12 years, and 13–18 years. A 3-level variable for each trauma type was constructed to assess chronicity of exposure: 0-trauma type not experienced, 1-trauma type experienced in only one epoch, and 2-trauma type experienced in multiple epochs.

Demographic variables

Demographic variables included age, gender, race/ethnicity, and current primary residence. Race and ethnicity were categorized as White (non-Hispanic), Black/African American (non-Hispanic), Hispanic/Latino, or Other. Primary residence, which denotes placement status, was classified as: home with parent/s, lives with other relatives, foster care, residential treatment center/correctional facility, or other.

UCLA PTSD-RI

The UCLA PTSD-RI (Steinberg, Brymer, Decker, & Pynoos, 2004; Steinberg & Brymer, 2008) assessed the past-month frequency and severity of PTSD symptoms. Items corresponded to DSM-IV symptom cluster criterion for B (intrusion), C (avoidance), and D (hyperarousal). Clinicians administered this standardized measure primarily as a self-report instrument or by clinical interview, given the developmental and clinical needs of the participants (e.g. limited literacy/comprehension for age). Twenty items directly assessed PTSD symptoms, and two additional items assessed associated fear of recurrence and guilt. Subscale scores for criterion scales and a total PTSD score were tabulated. Relevance to recent changes in DSM-5 and robust psychometric properties have been described previously (see Elhai et al., 2013; Steinberg et al., 2013). Here, internal consistency for each scale was good (PTSD total score: α = 0.86, B: α = 0.93, C: α = 0.92, D: α = 0.94).

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) 6–18

The CBCL, completed by a caregiver, is a widely-used 113-item questionnaire that yields scores for Total Behavioral Problems based on two broadband scales (Internalizing and Externalizing Behavioral Problems) and empirically-based syndrome scales that reflect emotional and behavioral problems and symptoms (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). The CBCL has been used in ethnically diverse populations and has consistently demonstrated strong psychometric properties. Here, the CBCL yielded Cronbach alphas greater than 0.98 for the Total, Internalizing, and Externalizing Behavior Problem scales.

Risk Behaviors

At baseline, a 3-point scale was used to rate the degree of functional impairment and severity of 14 problems reported by youth and their caregivers in the past 30 days. Three high risk behaviors—alcohol/substance abuse, suicidality, self-injurious behaviors—were assessed. The remaining items assessed functioning across a broad range of psychosocial domains and ecological contexts including home, school, and community. To remain consistent with previous analyses on the CDS and avoid skewness, the indicators were dichotomized by combining 1 (somewhat a problem) and 2 (very much a problem) vs. 0 (not a problem).

Data Analysis

The primary goal of the analysis was to discern if distinct classes of trauma exposure could be identified in the sample and, if so, which of the auxiliary variables had significant relationships with class membership. Analyses were performed using Mplus 7.1 and SAS 9.3. Descriptive statistics delineated sample characteristics. Latent class analysis (LCA), a type of mixture modeling, was used to identify subgroups based on variables categorizing exposure to each of the 14 PTE types. The sample was large enough to be divided via random selection into two nearly equal groups (n=1743 and n=1742). These groups did not differ significantly on any demographic characteristics. The first group was used to conduct exploratory latent class analysis (LCA) and the second was used for a confirmatory LCA. The results of the first group are reported in this paper. Because the number of classes was unknown, variables were entered into the LCA beginning with one class; additional classes were added incrementally until the model was no longer well defined (i.e., a unique solution could not be determined with maximum likelihood methods). Resulting models ranged from one to eight classes.

Each model was tested for fit using several measures. The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) is a quantitative index of model fit utilizing both the likelihood and number of model parameters, where lower values indicate more favorable fit (Schwarz, 1978). The Consistent Akaike’s Information Criterion (CAIC) and Approximate Weight of Evidence Criterion (AWE) use similar criteria as the BIC. The Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR) (Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001) provides between-model comparisons; non-significant values indicate the model with one additional class does not statistically improve fit over the current model. The Bayes Factor (BF) quantifies the extent to which the data favor the current model over the model with one more class by approximating the ratio of the probability of obtaining the sample data, assuming the current model is true, over the probability of obtaining the data assuming one additional class. The approximate Correct Model Probability (cmP) for a model is an approximation of the probability of a model being correct relative to the models we attempted. Entropy values (R2entr) were used to evaluate the quality and separation of classes indicated (Ramaswamy, DeSarbo, Reibstein, & Robinson, 1993). Lower entropy values for a model (range: 0–1) suggest classes that do not possess unique characteristics. A confirmatory latent class was performed on the second half of the complete sample. Meaningfulness and interpretability of PTE patterns within modeled classes were considered in selecting the final class structure. Class descriptions for the selected models were generated using results and related inferences from the 3-step method (Vermunt, 2010). This method (1) summarizes covariates and most likely class assignments in a multidimensional frequency table, (2) uses matrix multiplication to reweight the frequency counts by the inverse of the matrix of classification errors, and (3) uses multinomial logistic regression with the reweighted frequency table. This approach estimates the relationship of class membership with auxiliary variables of interest while adjusting for misclassification bias (Vermunt, 2010).

Results

Sample demographic characteristics, lifetime number of trauma types, and emotional and behavioral outcomes are presented in Table 1. Table 2 presents the percent of youth exposed to the 14 PTE types across the developmental epochs.

Table 2.

Percent of Adolescents with Each Type of Potentially Traumatic Event during Single vs. Multiple Developmental Epoch(s) and Overall (N=1,743)

| PTE Type | Exposure

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Developmental Epoch | Multiple Developmental Epochs | Overall | |

| Sexual Abuse/Maltreatment | 269 (15.4%) | 111 (6.4%) | 380 (21.8%) |

| Sexual Assault/Rape | 328 (18.8%) | 60 (3.4%) | 388 (22.2%) |

| Physical Abuse/ Maltreatment | 257 (14.7%) | 253 (14.5%) | 510 (29.3%) |

| Physical Assault | 218 (12.5%) | 55 (3.2%) | 273 (15.7%) |

| Emotional Abuse/Psychological Maltreatment | 215 (12.3%) | 383 (22.0%) | 598 (34.3%) |

| Neglect | 193 (11.1%) | 163 (9.4%) | 356 (20.4%) |

| Domestic Violence | 323 (18.5%) | 354 (20.3%) | 677 (38.8%) |

| Illness/Medical Trauma | 147 (8.4%) | 55 (3.2%) | 202 (11.6%) |

| Serious Injury/Accident | 241 (13.8%) | 28 (1.6%) | 269 (15.4%) |

| Traumatic Loss, Separation, or Bereavement | 727 (41.7%) | 260 (14.9%) | 987 (56.6%) |

| Impaired Caregiver | 185 (10.6%) | 424 (24.3%) | 609 (34.9%) |

| Extreme Interpersonal Violence | 124 (7.1%) | 28 (1.6%) | 152 (8.7%) |

| Community Violence | 242 (13.9%) | 142 (8.2%) | 384 (22%) |

| School Violence | 207 (11.9%) | 106 (6.1%) | 313 (18%) |

Note. Trauma types are not mutually exclusive.

Aim 1: LCA Classes

Table 3 summarizes key model fit indices. The minimum BIC occurred with the 5-class model. Examination of CAIC and AWE yielded similar results. The LMR indicated a simple 2-class model as most parsimonious. The 5-class model was the simplest model for which BF was of significant magnitude. The cmP heavily favored the 5 class model with a value of 1. Thus the quantitative and qualitative fit indices suggested the 5-class model best explained the data. Class enumeration results from the confirmatory LCA of the second half of the sample were similarly in favor of a 5-class model.

Table 3.

Model Fit Indices for Exploratory Latent Class Analysis

| Model | Log-Likelihood | # of Parameters | BIC | LRT | BFK, K+1 | cmPK |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Class | −16436 | 28 | 33080.94 | <.01 | <.10 | 0.0 |

| 2-Class | −15800.8 | 57 | 32027.04 | .16 | <.10 | 0.0 |

| 3-Class | −15586.6 | 86 | 31815.02 | .27 | <.10 | 0.0 |

| 4-Class | −15435.7 | 115 | 31729.73 | .17 | <.10 | 0.0 |

| 5-Class | −15300.1 | 144 | 31674.97 | .11 | >10 | 1.0 |

| 6-Class | −15236.3 | 173 | 31763.81 | .77 | >10 | 0.0 |

| 7-Class | −15181.4 | 202 | 31870.5 | .77 | >10 | 0.0 |

| 8-Class | −15132.8 | 231 | 31989.63 | .78 | >10 | 0.0 |

| 9-Class | Not well-identified | |||||

Note. BIC is the Bayesian Information Criteria, LRT is the p-value from the Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio comparing the K class model to the K+1 class model, BFK, K+1 is the Bayes Factor comparing the K class model to the K+1 class model. cmPK denotes correct model probability for the K class model. Boldface type denotes the best fitting model for each fit index.

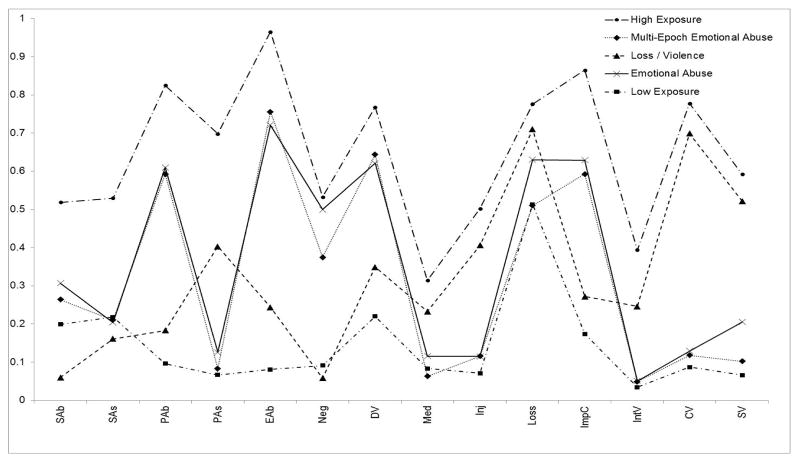

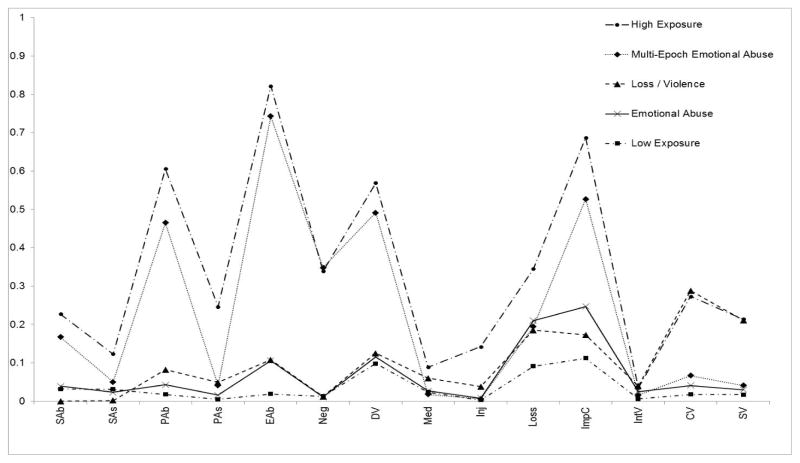

The classes were delineated by two factors: the proportion of youth in the class estimated to have experienced each PTE and whether traumas were experienced in >1 developmental epoch. Figure 1 summarizes the first factor by presenting overall trauma exposure for each subgroup, combining single and multiple epoch exposure. Figure 2 details further class distinctions by presenting estimated proportions of multi-epoch exposure for each subgroup. Of the five subgroups, four were classified by multiple PTE types. One polyvictimization subgroup that emerged can be characterized as a high exposure subgroup (M=10.0 trauma types). This subgroup had high exposure rates to several trauma types: physical abuse (82.5%), emotional abuse (96.5%), domestic violence (76.8%), traumatic loss/separation/bereavement (77.6%), impaired caregiver (86.5%), and community violence (77.8%). Additionally, several trauma types occurred in multiple developmental epochs: physical abuse (60.6%), emotional abuse (82.2%), domestic violence (56.9%), and impaired caregiver (68.7%).

Figure 1.

Detailed estimated probabilities of exposure to each PTE type. SAb=sexual abuse. SAs=sexual assault. PAb=physical abuse. PAs=physical assault. EAb=emotional abuse. Neg=neglect. DV=domestic violence. Med=illness or medical trauma. Inj=serious injury/accident. Loss=traumatic loss/separation. ImpC=impaired caregiver. IntV=extreme interpersonal violence. CV=community violence. SV=school violence.

Figure 2.

Probabilities of multi epoch exposure to each PTE for the 5-class model. SAs=sexual assault. PAb=physical abuse. PAs=physical assault. EAb=emotional abuse. Neg=neglect. DV=domestic violence. Med=illness or medical trauma. Inj=serious injury/accident. Loss=traumatic loss/separation. ImpC=impaired caregiver. IntV=extreme interpersonal violence. CV=community violence. SV=school violence.

Three polyvictimization subgroups had relatively moderate levels of trauma exposure: a multi-epoch emotional abuse subgroup (M =5.0 trauma types), an emotional abuse subgroup (M =6.1 trauma types), and a loss/violence exposure subgroup (M =5.4 trauma types). Of these, the multi-epoch emotional abuse subgroup had the largest estimated membership (19.2% of the sample). Multiple peaks in Figures 1 and 2 illustrate that this subgroup was distinguished by high rates of Emotional Abuse/Psychological Maltreatment, both overall (75.6%) and in multiple developmental epochs (74.3%). This subgroup also had relatively high multi-epoch exposure to physical abuse (46.5%), neglect (34.8%), domestic violence (49.1%), and an impaired caregiver (52.7%). The emotional abuse subgroup had relatively high exposure to trauma types similar to the multi-epoch emotional abuse subgroup; emotional abuse (72.1%), physical abuse (61.0%), domestic violence (62.1%), and an impaired caregiver (62.9%). However, as illustrated by the “flatness” of this group in Figure 2, the majority of PTEs in this subgroup occurred in only one epoch. In contrast, the loss/violence exposure group was distinguished by higher exposure rates to traumatic loss/separation/bereavement (71.0%) and community violence (69.9%).

The final subgroups demonstrated relatively low numbers of PTEs, and thus was considered a non-polyvictimization profile, or low exposure subgroup. This group represents approximately half of the sample (51.2%). This subgroup had a comparably low average number of lifetime trauma types (M =2.2 trauma types). Though not distinguished by particularly high rates of any one trauma, traumatic loss/separation/bereavement was the most common trauma type in this group affecting half the sample (51.3%).

The confirmatory analysis on the second half of the sample revealed 5 classes with the same distinct characteristics. Specifically, it revealed a high exposure subgroup (5.1%), multi-epoch emotional abuse subgroup (17.4%), an emotional abuse subgroup (10.6%), and a loss/violence exposure subgroup (18.3%), and a low exposure subgroup (48.6%). The only distinct difference in in this model was that the high exposure subgroup in the confirmatory sample had even higher rates of distinct trauma types than the exploratory sample.

Aim 2: Demographic and Clinical Covariates across Classes

Multinomial logistic regression was used to determine which variables were significantly related to class membership. Class-specific estimates derived from multinomial logistic regression models are presented in Table 4. As seen in Table 4, gender, race, primary residence, and number of PTE types experienced were statistically significant predictors of class membership. For example, being male was associated with increased likelihood of being in the loss/violence subgroup and a decreased likelihood of being in the high exposure subgroup. Conversely, females were estimated to be overrepresented in the emotional abuse and high exposure subgroups.

Table 4.

Demographic Characteristics, Lifetime Number of Trauma Types, and Emotional and Behavioral Functioning Estimated for 5-Class LCA Model

| Variable | High Exposure | Multi-Epoch Emotional Abuse | Loss/Violence | Emotional Abuse | Low Exposure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of total sample | 5.0% | 19.2% | 14.5% | 10.1% | 51.2% |

|

| |||||

| Gender* ( , R2=0.05, p<0.001) | |||||

| Male | 21.8% | 33.1% | 51.7% | 30.5% | 39.6% |

| Female | 78.2% | 66.9% | 48.3% | 69.5% | 60.4% |

| Race/Ethnicity* ( , R2=0.02, p=0.002) | |||||

| White (Non-Hispanic) (REF) | 50.3% | 48.9% | 9.1% | 54.7% | 29.7% |

| Black/African American (Non-Hispanic) (p<.001) | 9.9% | 14.8% | 20.9% | 20.3% | 30.6% |

| Hispanic/Latino (p=.01) | 25.5% | 30.7% | 64.9% | 19.8% | 34.6% |

| Other (p=.21) | 14.4% | 5.6% | 5.1% | 5.3% | 5.1% |

| Primary Residence* ( , R2=0.02, p=0.012) | |||||

| Home with parent(s) (REF) | 43.2% | 45.7% | 71.1% | 51.2% | 72.4% |

| With relatives (p=.38) | 10.8% | 13.2% | 14.0% | 17.1% | 12.1% |

| Foster Care (p=.02) | 11.5% | 14.4% | 1.1% | 15.9% | 6.6% |

| Residential treatment/Correctional facility (p<.001) | 28.2% | 17.2% | 10.1% | 12.0% | 3.7% |

| Other (p=.24) | 6.2% | 9.4% | 3.6% | 3.8% | 5.3% |

| Lifetime Number of Trauma Types, M (SD)* | 10.0 (0.20) | 5.0 (0.10) | 5.4 (0.14) | 6.1 (0.17) | 2.2 (0.05) |

| CBCL, M (SE) | |||||

| Externalizing Behavior Problems* ( , p<0.001) | 66.7 (1.4) | 63.4 (0.73) | 65.1 (0.99) | 65.4 (1.03) | 61.0 (0.46) |

| Internalizing Behavior Problems ( , p=0.035) | 67.8 (1.31) | 63.6 (0.71) | 63.5 (1.15) | 63.0 (1.10) | 60.9 (0.49) |

| Total Behavior Problems* ( , p=0.001) | 67.7 (1.34) | 64.3 (0.69) | 65.0 (0.96) | 66.0 (0.98) | 61.9 (0.44) |

| CBCL Scores - Clinical Range | |||||

| Externalizing Behavior Problems * ( , R2=0.01, p=0.03) | 70.2% | 53.5% | 58.1% | 72.6% | 43.5% |

| Internalizing Behavior Problems * ( , R2=0.02, p<0.001) | 70.6% | 54.4% | 54.2% | 54.5% | 42.4% |

| Total Behavior Problems * ( , R2=0.01, p=.03) | 75.7% | 62.5% | 59.8% | 73.7% | 48.5% |

| UCLA PTSD-RI Overall Score, M (SE)* ( , p<0.001) | 37.0 (1.57) | 27.8 (0.94) | 27.4 (1.06) | 25.7 (1.32) | 25.2 (0.58) |

| UCLA PTSD-RI Scores – Clinical Range | |||||

| Re-experiencing*( , R2=0.04, p<0.001) | 89.1% | 77.2% | 79.6% | 75.2% | 73.8% |

| Avoidance*( , R2=0.05, p<0.001) | 83.6% | 56.2% | 51.8% | 48.9% | 50.3% |

| Hyperarousal*( , R2=0.04, p<0.001) | 95.4% | 81.1% | 83.5% | 79.3% | 73.0% |

| Overall Score*( , R2=0.04, p<0.001) | 57.3% | 29.4% | 26.1% | 19.9% | 20.9% |

| Risk Behaviors | |||||

| Alcohol/Substance Abuse*( , R2=0.06, p<0.001) | 34.5% | 14.1% | 18.5% | 18.3% | 21.0% |

| Suicidality*( , R2=0.04, p<0.001) | 42.6% | 34.1% | 22.5% | 28.4% | 20.5% |

| Self-injurious Behaviors*( , R2=0.04, p<0.001) | 27.1% | 25.1% | 10.2% | 23.0% | 13.6% |

Note. Estimates are based on multinomial logistic regression analysis of class membership with associated demographic characteristic.

Indicates class membership statistically depended on indicator in multinomial logistic models. p values reported assume the Low Exposure group as the reference class. CBCL=Child Behavior Checklist.

Table 4 also delineates the LCA results for class membership and indicators of emotional and behavioral functioning, including internalizing (CBCL), externalizing (CBCL), traumatic stress (UCLA PTSD-RI), and risk behaviors (i.e., alcohol/substance use, suicidal ideation, and self-injurious behaviors). For all variables measured, class membership was significantly related to emotional and behavioral measures; specific findings are highlighted and discussed below.

Discussion

The first goal of this study was to identify and characterize groups or profiles based on patterns of victimization and trauma exposure among a large clinic-referred sample of adolescents. Several key findings paralleled past research with community (e.g., Finkelhor et al., 2011; Ford et al., 2010) and clinical (e.g., Alvarez-Lister et al., 2014; Ford et al., 2011) samples, but several important differences also emerged. First, multiple unique trauma profiles were observed among our sample of clinic-referred adolescents. In national community and clinic-referred samples, the most prevalent trauma profiles were those characterized by few (i.e., 1–3) trauma types, such as witnessed violence, traumatic loss, or accidents. In the current study, four of the five identified profiles involved polyvictimization compared to four of seven identified profiles in a nationally representative sample that used a similar data analytic approach (Ford et al., 2010). Moreover, in the current sample, 48.6% of youth were exposed to lifetime polyvictimization as compared to 25–30% in national community samples (Turner et al., 2010; Ford et al., 2010), suggesting polyvictimized youth are overrepresented in clinical settings. This may reflect the well-documented tendency for polyvictimized youth to experience greater symptomology than youth with less complex trauma histories (Finkelhor et al., 2007; Ford et al., 2010; Ford et al., 2011; Turner et al., 2010). In prior studies where victimization subgroups have been identified empirically among youth in outpatient clinics, the prevalence of polyvictimization has been somewhat lower (i.e., 8–12%; Alvarez-Lister et al., 2014; Ford et al., 2011) than in the current study. Closer examination of the composition of the polyvictimization profiles in those studies reveals that those groups were generally characterized by higher rates of overall trauma exposure than most polyvictimization classes identified in this study. The much larger sample size in the current study may have facilitated identification of a more nuanced and diverse polyvictimization taxonomy than was possible in prior studies conducted in outpatient mental health clinics, thus also allowing more polyvictimized youth to be identified and differentiated based on their trauma histories.

The second goal was to evaluate associations between identified trauma exposure profiles and demographic factors, as well as clinically relevant outcomes. Several demographic characteristics were associated with class membership. Boys were overrepresented in the loss/violence subgroup, whereas girls were more likely to be classified in the high exposure and emotional abuse subgroups. This may reflect links with specific PTE types that compose respective profiles. For instance, compared to other moderate and low trauma exposure groups, the loss/violence subgroup demonstrated high rates of community and school violence, and somewhat elevated prevalence of physical assault, three types of PTEs that are more commonly experienced by boys (Finkelhor et al., 2013; McLaughlin et al., 2013). Meanwhile, the high exposure, emotional abuse, and multi-epoch emotional abuse subgroups reveal somewhat elevated rates of sexual abuse, which is more prevalent among girls (Finkelhor et al., 2013).

Ethnicity findings were partially congruent with previous studies. Whereas African-American youth were found to be disproportionately affected by traumatic loss in nationally representative community samples (Rheingold et al., 2004), in the current study Hispanic/Latino youth were overrepresented in the loss/violence subgroup. This finding is consistent with prior work linking minority status to elevated risk for adversity (e.g., McLaughlin et al., 2013). However, youth from minority backgrounds were underrepresented in the high exposure class. Also consistent with prior findings, racial/ethnic minority status did not appear to increase risk for inclusion in other polyvictimization subgroups (Finkelhor et al., 2009; Ford et al., 2011). Instead, contrary to past research, White adolescents were overrepresented in the high exposure, multi-epoch emotional abuse, and emotional abuse classes. Continued research should examine whether these findings represent true differences in polyvictimization profiles between community and clinical samples, are artifacts of different methods of assessing race and ethnicity and trauma exposure, or reflect racial disparities in access to mental health services among youth with complex trauma histories (Martinez, Gudiño, & Lau, 2013).

With regard to clinical outcomes of identified victimization profiles, a dose-response relation was observed between the number of PTEs experienced and psychological distress. The high-exposure group, who experienced an average of 10 types of trauma during their lives, was at greatest risk for negative outcomes including residential treatment/correctional placement; internalizing, externalizing, and PTSD scores in the clinical range; and engagement in substance use and suicidal behaviors. The moderate exposure subgroups (multi-epoch emotional abuse, loss/violence, and emotional abuse profiles) were more at-risk for internalizing and externalizing symptoms than the low exposure subgroup but did not differ appreciably from each other. These findings align with prior reports on the positive relationship between number of victimization types and psychiatric symptoms (e.g., Alvarez-Lister et al., 2014; Finkelhor et al., 2011). Notably, although 5% of youth in low exposure subgroups met criteria for PTSD in a national community sample (Ford et al., 2010), 21% of youth in the low exposure subgroup identified here evinced clinically significant overall scores on the UCLA PTSD-RI. This higher prevalence of PTSD in the low exposure subgroup may reflect successful efforts to link symptomatic youth to trauma-focused clinical assessment, even in the case of low or limited exposure. Taken together, findings concerning the frequency and consequences of polyvictimization further validate—within a clinical sample—the importance of understanding an adolescent’s overall trauma history rather than a single event.

Developmental epochs were incorporated into the LCA to determine whether chronicity distinguished polyvictimization profiles. Overall, chronicity did not appear to be a key predictor of worse outcomes among polyvictimized youth beyond number and types of traumatic experiences. However, two profiles demonstrated high rates of emotional abuse (emotional abuse and multi-epoch emotional abuse profiles) in addition to 4–5 other types of trauma exposure, but differed on the timing of emotional abuse. The two subgroups evinced highly similar patterns of association with clinical outcomes. Two exceptions were PTSD avoidance symptoms and suicidality, which were more common in the multi-epoch emotional abuse class than the other emotional abuse subgroup or in the loss/violence or low exposure subgroups. This finding may reflect a more durable or long-standing pattern of maladaptive thinking and coping that can develop following exposure to emotional abuse at a young age that continues over time (Gibb & Abela, 2008). It is important to note that although rates of emotional abuse were higher in those two profiles than the loss/violence or low exposure groups, emotional abuse co-occurred with several other types of maltreatment and trauma in both groups. Hence, it is not possible to tease apart the unique role of emotional abuse in this study.

Limitations and Research Implications

This study expands the polyvictimization literature by focusing on a large sample of clinic-referred adolescents, but several limitations should be noted. First, the study utilized a cross-sectional design, which limits capacity to evaluate causal influences between trauma and clinical outcomes. Future studies should utilize both prospective and retrospective methods to untangle the causal pathways connecting polyvictimization to clinical outcomes. Future work should also assess factors across multiple levels of measurement (e.g., genetic, neurobiological, cognitive, social) to identify moderators and mediators of polytraumatization and psychological health. These approaches may uncover novel ways to characterize the cumulative impact of multiple traumatic experiences and other co-occurring risk factors on psychological well-being (Layne et al., 2014; Sameroff, 2000).

Second, a limited number of clinical outcomes were included within the study. Polyvictimization has been implicated in a variety of additional clinical consequences, including other mental health problems, risky sexual behavior, and sleep disturbances (Briere et al., 2008; Briggs et al., 2012; Ford et al., 2010; Macdonald, Danielson, Resnick, Saunders, & Kilpatrick, 2010). Additional studies should investigate whether these constructs are associated within polyvictimization subgroups. Relatedly, internalizing and externalizing symptoms were assessed broadly here, rather than specific clinical diagnoses. Given that treatment implications vary by disorder, future research should investigate the relation between victimization and trauma exposure profiles and distinct diagnoses. By better understanding the clinical impact of these polyvictimization profiles, future investigations could examine the effects of existing evidence-based interventions for trauma-related problems among polyvictimized youth, as well as the utility of emerging integrated treatments in this population.

Third, a variety of methods were used to obtain the data reported here, including self-caregiver-, and clinician-report. Where multiple data sources were not consistently obtained, gaps may exist in knowledge of trauma history or psychosocial functioning. Whenever possible, self-reported information regarding trauma exposure and psychological distress should be obtained in addition to information gathered from other sources, given different respondents may offer disparate reports (de los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005).

Finally, the study was conducted before the release of DSM-5 criteria, so DSM-IV scales were used to assess PTSD. Recent factor analytic evidence suggests high coherence between DSM-IV and DSM-5 with regard to overall clinical significance (Elhai et al., 2013). Given similar observed associations between the LCA profiles and PTSD and CBCL internalizing scales, we anticipate that the findings here would be stable if DSM-5 PTSD scales were used.

Clinical and Policy Implications

Given that roughly half of adolescents exposed to one PTE report polyvictimization, findings have significant implications in clinical services for adolescents. Results provide support for the existence of distinct polyvictimization profiles among clinic-referred adolescents, and for the notion that it is important to understand particular combinations of trauma exposure rather than simply counting PTEs. Thus, results underscore the need to thoroughly assess multiple forms of traumatic events and victimization types when working with youth in mental health settings, even though youth may present for specific events. This can help guide treatment planning, particularly since more complicated victimization histories are associated with more severe emotional and behavioral problems. Notably, many youth in the sample had experienced few types of trauma. It is encouraging that these youth were referred to clinical services, as intervention following initial PTE experiences may be especially effective in ameliorating symptoms and preventing revictimization. Clinicians, advocates, and policymakers should continue to identify and implement strategies for ensuring that these vulnerable youth receive evidence-based interventions in a timely fashion to promote recovery from trauma and resilience.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by SAMHSA Grant #s 2U79SM054284-12S, U79SM061269, NIMH Grant T32-MH018869-25 (sponsoring Dr. Cohen), and NIDA Grants K12 DA031794 and K23 DA038257 (sponsoring Dr. Adams). Funders did not play a role in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the attached manuscript, or in the decision to submit this manuscript for publication. The views presented in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily the sponsor. Thank you to the NCTSN sites and families that participated in data collection.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Lister MS, Pereda N, Abad J, Guilera G, GReVIA Polyvictimization and its relationship to symptoms of psychopathology in a southern European sample of adolescent outpatients. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38:747–756. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Kaltman S, Green BL. Accumulated childhood trauma and symptom complexity. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21(2):223–226. doi: 10.1002/jts.20317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs EC, Fairbank JA, Greeson JK, Layne CM, Steinberg AM, Amaya-Jackson LM, Pynoos RS. Links between child and adolescent trauma exposure and service use histories in a national clinic-referred sample. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2013;5(2):101. doi: 10.1037/a0027312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Spinazzola J, Ford J, Lanktree C, Blaustein M, Cloitre M, van der Kolk B. Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals. 2005;35:390–398. [Google Scholar]

- Cyr K, Chamberland C, Clement ME, Lessard G, Wemmers JA, Collin-Venina D, Damant D. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37:814–820. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: a critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(4):483. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano C, Kamphaus RW. Investigating Subtypes of Child Development A Comparison of Cluster Analysis and Latent Class Cluster Analysis in Typology Creation. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2006;66(5):778–794. doi: 10.1177/0013164405284033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Layne CM, Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Briggs EC, Ostrowski SA, Pynoos RS. Psychometric Properties of the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index. Part II: Investigating Factor Structure Findings in a National Clinic-Referred Youth Sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26(1):10–18. doi: 10.1002/jts.21755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Graham JC, Litrownik AJ, Everson M, Bangdiwala SI. Defining maltreatment chronicity: Are there differences in child outcomes? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(5):575–595. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31(1):7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H. Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:149–166. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070083. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407070083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA, Hamby SL. Measuring poly-victimization using the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(11):1297–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, Holt M. Pathways to polyvictimization. Child Maltreatment. 2009;14:316–329. doi: 10.1177/1077559509347012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Violence, crime, and abuse exposure in a national sample of children and youth: An update. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167(7):614–621. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Connor DF, Hawke J. Complex trauma among psychiatrically impaired children: a cross-sectional, chart-review study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009;70(8):1155–1163. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Elhai JD, Connor DF, Frueh BC. Poly-victimization and risk of posttraumatic, depressive, and substance use disorders and involvement in delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(6):545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Wasser T, Connor DF. Identifying and determining the symptom severity associated with polyvictimization among psychiatrically impaired children in the outpatient setting. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16(3):216–226. doi: 10.1177/1077559511406109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Abela JR. Emotional abuse, verbal victimization, and the development of children’s negative inferential styles and depressive symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32(2):161–176. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9106-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JC, English DJ, Litrownik AJ, Thompson R, Briggs EC, Bangdiwala SI. Maltreatment chronicity defined with reference to development: Extension of the social adaptation outcomes findings to peer relations. Journal of Family Violence. 2010;25(3):311–324. doi: 10.1007/s10896-009-9293-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greeson JK, Briggs EC, Kisiel CL, Layne CM, Ake GS, III, Ko SJ, Fairbank JA. Complex trauma and mental health in children and adolescents placed in foster care: findings from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Child Welfare. 2011;90:91–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplow JB, Widom CS. Age of onset of child maltreatment predicts long-term mental health outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:176–187. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.116.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Conceptualizing the challenge of reducing interpersonal violence. Psychology of Violence. 2011;1(3):166. doi: 10.1037/a0022990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(4):692. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE. A dimensional-spectrum model of psychopathology: progress and opportunities. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(1):10–11. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layne CM, Briggs E, Courois C. Introduction to the Special Section: Unpacking risk factor caravans across development: Findings from the NCTSN Core Data Set. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy. 2014;6(Suppl 1):S1–S8. doi: 10.1017/S0954579497001107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88(3):767–778. doi: 10.1093/biomet/88.3.767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald A, Danielson CK, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. PTSD and comorbid disorders in a representative sample of adolescents: The risk associated with multiple exposures to potentially traumatic events. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34(10):773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT. Advances in research definitions of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:425–439. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez JI, Gudiño OG, Lau AS. Problem-specific racial/ethnic disparities in pathways from maltreatment exposure to specialty mental health service use for youth in child welfare. Child Maltreatment. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1077559513483549. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Hill ED, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(8):815–830. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos RS, Fairbank JA, Steinberg AM, Amaya-Jackson L, Gerrity E, Mount ML, Maze J. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network: Collaborating to improve the standard of care. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39(4):389. doi: 10.1037/a0012551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy V, DeSarbo WS, Reibstein DJ, Robinson WT. An empirical pooling approach for estimating marketing mix elasticities with PIMS data. Marketing Science. 1993;12(1):103–124. doi: 10.1287/mksc.12.1.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rheingold AA, Smith DW, Ruggiero KJ, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. Loss, trauma exposure, and mental health in a representative sample of 12–17-year-old youth: Data from the national survey of adolescents. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2004;9(1):1–19. doi: 10.1080/15325020490255250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ. Dialectical processes in developmental psychopathology. In: Sameroff A, Lewis M, Miller S, editors. Handbook of developmental psychopathology. 2. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2000. pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Spinazzola J, Hodgdon H, Ford JD, Briggs EC, Liang L, Layne CM, Stolbach B. Unseen wounds: The contribution of psychological maltreatment to child and adolescent mental health and risk outcomes. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, S1. 2014:S18–S28. doi: 10.1037/a0037766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg AM, Brymer M, Decker K, Pynoos RS. The UCLA PTSD Reaction Index. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2004;6:96–100. doi: 10.1007/s11920-004-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Kim S, Briggs EC, Ippen CG, Ostrowski SA, Pynoos RS. Psychometric properties of the UCLA PTSD reaction index: part I. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26(1):1–9. doi: 10.1002/jts.21780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner H, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. Poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010b;38:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK. Latent class modeling with covariates: two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis. 2010;18:450–469. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpq025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]