Abstract

Ventilator induced lung injury (VILI), often attributed to over-distension of the alveolar epithelial cell layer, can trigger loss of barrier function. Alveolar epithelial cell monolayers can be used as an idealized in vitro model of the pulmonary epithelium, with cell death and tight junction disruption and permeability employed to estimate stretch-induced changes in barrier function. We adapted a method published for vascular endothelial permeability, compare its sensitivity with our previously published method, and determine the relationship between breeches in barrier properties after stretch and regions of cell death After 4-5 days in culture, primary rat alveolar epithelial cells seeded on plasma treated polydimethylsiloxane membrane coated with biotin-labeled fibronectin, or fibronectin alone were stretched in the presence of FITC-tagged streptavidin (biotin-labeled membrane) or BODIPY-ouabain. We found that the FITC-labeling method was a more sensitive indicator of permeability disruption, with significantly larger positively stained areas visible in the presence of stretch and with ATP production inhibitor Antimycin-A. Triple-stained images with Hoescht (nuclei), Ethidium Homodimer (EthD, damaged cell nuclei) and FITC (permeable regions) were used to determine that within permeable regions intact cells were positioned closer to damaged cells than in non-permeable regions. We concluded that local cell death may be an important contributor to barrier integrity.

Keywords: tight junction, barrier properties, lung, acute lung injury, pulmonary transport

Introduction

Mechanical ventilation with large tidal volumes may produce over-distension of alveolar epithelium, resulting in ventilator induced lung injury (VILI) and barrier dysfunction associated with increased protein in the alveolar space, which increases osmotic transport of interstitial fluid into the airspace, lung wet weight, and permeability (17, 21, 31, 33). Similarly, in vitro models of mechanical ventilation, whereby cell monolayers are stretched at physiologically relevant magnitudes, have revealed that large stretch levels increase permeability, typically measured as a flux of radio-labeled or fluorescently tagged macromolecules from apical to basal sides of the cell monolayer (18, 19, 30) or transport of charged tracers measured via increased transepithelial/endothelial electrical resistance (TER) across the cell monolayer (9, 12, 26, 28). Given the paucity of permeable and distensible cell monolayer substrate materials, recently we reported permeability measurement whereby BODIPY-tagged ouabain (BO) in the apical media is able to bind to basolateral Na+-K+ ATPase pumps on epithelial cells that are only accessible when tight junction barrier properties are compromised (Figure 1A) (8, 11, 12, 14-16, 22, 37). This method is specific to epithelial cells, and is sensitive to the stretch-induced variation in the number of Na+-K+ ATPase pumps on the cell membrane (14). Beginning with a novel method for endothelial cells, we present a modified, highly sensitive method to measure transport of FITC-tagged avidin from the apical medium that binds to a biotin-labeled collagen coating on an impermeable monolayer substrate only when epithelial barrier function is disrupted (Figure 1B) (18). Previously we reported that large stretch magnitudes may compromise regional barrier integrity via disruption and reorganization of local tight junctions (TJs) between intact or damaged cells in the epithelial cell monolayer, and by formation of denuded regions as cells dissociated from the stretchable membrane (7, 8, 11, 15). We use this new FITC-tagging method to test our hypothesis that after stretch, regions with increased permeability are spatially related to the location of damaged adherent cells, rather than to locations of intact cells with compromised tight junctional integrity or as a result of the formation of large cell-free zones in the alveolar epithelial cell monolayers.

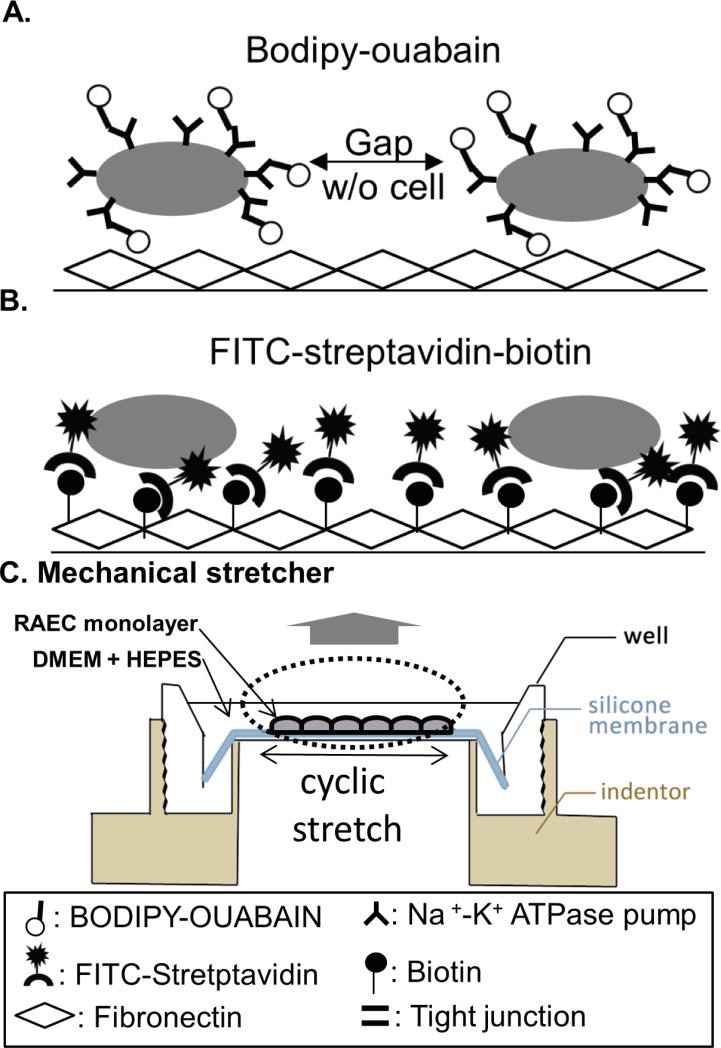

Figure 1. Comparative schematic of permeability assessments of stretched monolayers.

A) With tight junction TJ disruption, BODIPY-tagged ouabain (BO) has access to cell basolateral surfaces and binds to Na+-K+ ATPase pumps located on the basolateral membranes of rat alveolar epithelial cells (RAECs). B) When TJ integrity fails or cell-membrane contacts rupture, FITC-tagged streptavidin binds to the biotinylated fibronectin-coated PDMS membrane. C) Custom-designed cyclic stretch device expands RAEC monolayers seeded on fibronectin-coated PDMS membranes, creating a uniform, equi-biaxial deformation field (34).

Materials and Methods

Isolation and culture of rat alveolar epithelial cells (RAECs)

Type II alveolar epithelial cells were isolated from male Sprague-Dawley rats (250~400g, n=3-14/per group) as described previously (14-16), and seeded at a density of 106 cells/cm2 on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) silastic membranes (Specialty Manufacturing, Inc) with one of two treatments: fibronectin coating or biotinylated fibronectin, 42 μg/ml in MEM, (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). Fibronectin was biotinylated using EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-LC-Biotin, 230 nM, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). After one hour of suspension, the biotinylated fibronectin (B-FN) was coated onto O2-plasma (Technics, Technics Inc.) treated PDMS membranes. The O2-plasma treatment generates negative charges to reduce hydrophobicity of the surface (23, 32), and is necessary to enhance the biotinylated fibronectin attachment to the membrane and promote cell adhesion (36). In addition, fibronectin was coated on untreated and treated membranes to identify the role of plasma treatment in stretch-induced barrier disruption, as measured using the BO method. After 4-5 days in culture conditions with MEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), primary RAECs exhibit Type I RAEC characteristics (2, 13) and form a monolayer with tight junction proteins (TJs) and selective permeability that mimics intact alveoli (5, 7, 10, 12).

Mechanical stretch of RAEC monolayers

Monolayer wells, randomly assigned to experimental groups (3 wells from each rat were used in every experimental group,, and n=3-14 rats were included in each experimental group), were serum deprived in DMEM with 20mM HEPES for an hour prior to stretch studies isolate responses of the RAECs from any potential stretch-associated reactivity to cytokines, growth factors, and enzymes in serum. For those RAEC monolayers on fibronectin-coated (FN) membranes, BODIPY-ouabain (BO) (2μM; in DMEM+HEPES; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added to the apical media to identify regions where BODIPY is bound to basolateral Na+-K+ ATPase pumps that are exposed when TJ dysfunction permits paracellular transport to the intercellular region (Fig.1A). In all biotinylated fibronectin-coated (B-FN) wells with RAECs, FITC-streptavidin (25 μg/ml in DMEM+HEPES; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), Ethidium Homodimer (EthD, 35 μl/ml; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Hoechst (0.5 μl/ml; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added to the apical media prior to stretch to co-localize FITC-stained regions with damaged cells and with adherent cell nuclei from intact and damaged cells (Fig. 1B).

Monolayers on each of the two PDMS coatings were assigned to one of 4 study groups: equibiaxially stretched in our custom-designed system (34) at 0% (unstretched controls), 12%, 25%, and 37% change in surface area (ΔSA) for 10 min at 0.25 Hz (Fig.1C), equivalent to inflations from functional residual capacity to 64%, 86%, and 100% total lung capacity (34), respectively. In previous studies we reported that 10 minutes was sufficient to reorganize actin, alter TJ content and configuration, and cell-cell spacing, and permeability(7, 11, 14, 15, 35). As a positive control for TJ disruption, unstretched RAEC monolayers were treated with Antimycin-A (AMA, 10 μM in DMEM, n= 3 rats), previously shown to cause ATP depletion and tight junction disruption (1, 4, 14), or designated as vehicle controls (VC) and provided with 1μl of DMSO per 1ml of DMEM+HEPES.

Quantification of monolayer permeability and cell death

After stretch or antimycin-A treatment, monolayers were rinsed three times with DMEM+HEPES. Three image fields per well were captured by epifluorescence microscope (Nikon, TE300, Melville, NY), maintaining all image capture settings for all wells generated from a single rodent subject used as a cell source. Using a customized analysis program (Matlab, Mathworks, Natick, MA), the background FITC or BODIPY intensity was defined as the average field intensity obtained from the unstretched vehicle wells. To quantify stretch-induced permeability, the fields from stretched wells or antimycin-A treated wells were analyzed and the percent of the field with FITC-streptavidin-biotin (FITC-SB) or BO values above the threshold was determined for each field, averaged across the three fields and wells in a group, to yield cohort sizes 3-14 rats per group which were compared across stretch conditions and coatings.

In the triple-labeled images from the B-FN coated wells, the number of damaged cells (EthD) were divided by the number of cell nuclei (Hoechst) in every field (ImageJ, NIH, Bethesda, MD) to determine the percent of damaged cells, and values from the 3 fields per well were averaged.

Colocalization of cell death and permeable monolayer regions

To evaluate our hypothesis that regions with damaged cells were also the permeable regions in the FITC-SB wells, we created a customized routine in Matlab to classify all intact cells as being located in permeable (FITC-positive) or impermeable (FITC-negative) locations, and determine the nearest-neighbor distance between intact cells and damaged cells. Shorter live-damaged cell distances in permeable regions than impermeable regions would confirm our hypothesis that damaged cells are preferentially associated with permeable regions. The routine had four components: identify cells; classify them as intact or damaged; designate them as residing in permeable or impermeable regions; define the nearest-neighbor distance between every intact cell and the closest damaged cell. The cell identification component consisted of using Hoechst images to distinguish cell nuclei from spurious noise. Briefly, because Hoechst was very nucleus-specific, the Hoechst positive detection threshold for each rat was defined as the average Hoechst intensity in the three unstretched images obtained for that rat. All pixels above this threshold were considered Hoechst-positive in the stretched cell images . Using ImageJ, clusters of pixels larger than 25μm2 were designated as “nuclei” because epithelial cell nuclei are typically ≥7μm in diameter (38.4μm2)(3) The next step was to identify those nuclei considered damaged, by overlaying the EthD images and Hoechst images. EthD positive regions were identified using a similar threshold and cluster definition method, with one difference. Because EthD had lower specificity to the nucleus and higher background intensity, the threshold employed for identifying EthD positive nuclei was the mean of the EthD signal in the unstretched images plus one standard deviation. After overlaying EthD images and Hoechst images, we defined intact cell nuclei as Hoechst-only stained nuclei, and “damaged” nuclei as those with both Hoechst and EthD positive staining.. Our third step was to classify cells as residing on permeable regions (FITC positive), or impermeable (FITC negative) of the monolayer. We created idealized cell boundaries by extending Hoechst-stained nuclei digitally radially outward from the nucleus by 1.3μm, increasing pixel regions two to three-fold to capture some of the cytoplasmic area in a conservative manner. When these irregular “cell” boundaries overlapped, a commercial watershed image analysis routine (The MathWorks, Inc.) was employed to create separate cell regions, allocating that region to one cell or the other. These idealized cell maps were overlaid with the FITC images, and cells were designated as located in permeable or impermeable regions. Because monolayer barrier property integrity is determined at the tight junction rather than the nucleus, any portion of the cell could reside in a permeable region to be classified as permeable. Finally, in the fourth and final step, we determined the spacing between every intact cell centroid in a permeable zone and the centroid of its nearest damaged cell neighbor, and averaged the results for the image field. Similarly, we calculated the distance between every intact cell centroid in an impermeable zone and the centroid of its nearest damaged neighbor, and averaged for the image field.

Statistical analysis

Every experiment was performed on n=3 wells obtained from at least three animals, with 3 image field replicates obtained from every well, and wells within a rat averaged. Data is presented as the average across all rats, and error bars express the standard error of the mean (SEM). Stretch magnitude and method (FITC-SB and BO) were compared via a two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's HSD post-hoc analysis. Similar methods were used to compare nearest-neighbor distances in the permeable and impermeable regions. One-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD post-hoc analysis was applied to evaluate the influence of stretch on the number of damaged cells. For all analyses, significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

Bodipy-ouabain method vs. FITC-streptavidin-biotin method

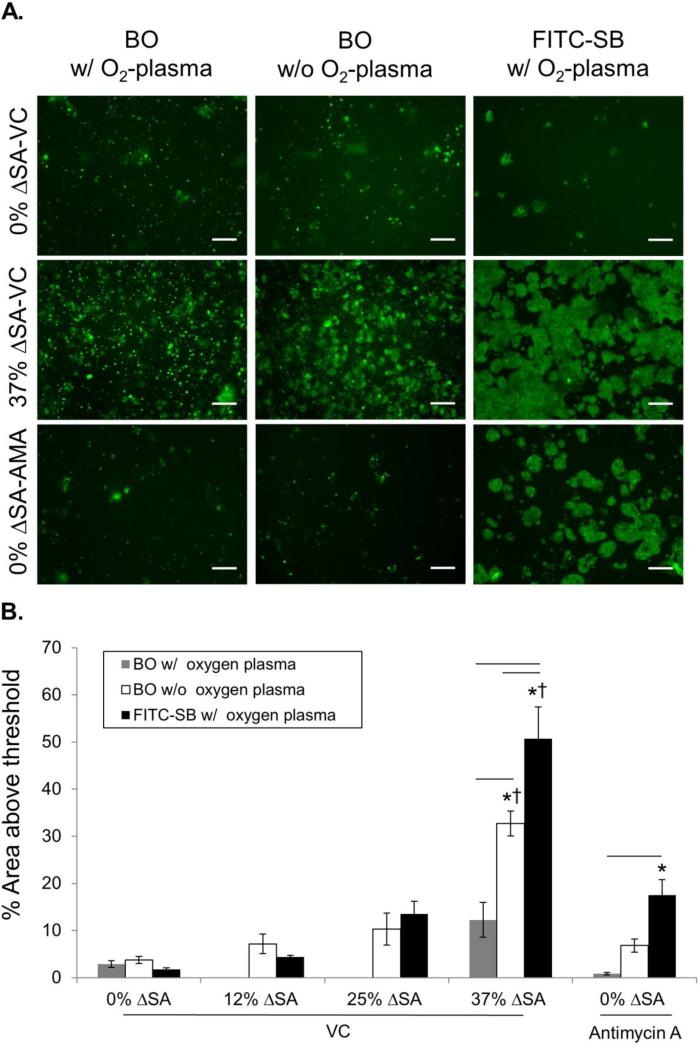

Comparing the new FITC-SB method with plasma treatment (Fig. 2 black bars) and our previously published BO method without plasma treatment (Fig. 2 white bars) revealed that 37% ΔSA cyclic stretch for 10 min significantly increased permeability above unstretched monolayers and lower stretch levels of 12% and 25% ΔSA for both methods, as indicated by increased stained region area (Table S1; FITC-SB, 50.71 ± 6.74%; BO 32.68 ± 2.64 % without plasma treatment). Furthermore, using both methods, permeability produced by stretch at 37% ΔSA was even larger than unstretched wells treated with Antimycin-A (AMA) to disrupt TJs. Because the FITC-SB area was significantly larger than BO area at 37% ΔSA, and because only the FITC-SB method revealed increases in permeability with Antimycin-A which were significantly larger (17.51 ± 3.27%) than unstretched VC wells, we conclude that the FITC-SB method is more sensitive to TJ disruption that our previously published BO method.

Figure 2. Assessment method, stretch magnitude and membrane treatment alter monolayer permeability measurement.

A. Representative micrographs of BODIPY-ouabain (BO) and FITC-Streptavidin-Biotin (FITC-SB) stained (green) areas in stretched (10 min, 37% ΔSA) and unstretched RAEC monolayers with and without AMA treatment. Bar =100 μm. B. These images were enhanced after analysis to enhance visibility for publication. Permeable area, as a percent of the total field, comparing FITC-SB (n=5 with O2 plasma treatment), BO with (n=3~5) and without (n=5~14) plasma treatment for stretch at 0%, 12%, 25%, 37% change in surface area (ΔSA), and with AMA in unstretched monolayers. Mean±SEM. Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference from 0% ΔSA with VC in each method; Dagger (†) indicates significant differences from 12%, 25% ΔSA with VC and 0% ΔSA with AMA; and bars indicates significant differences between methods in each experimental group.

O2-plasma treatment effect

Our previously published BO method did not rely on O2-plasma treatment. In contrast, the new FITC-SB method required O2-plasma treatment of the PDMS membrane to create a uniform distribution of B-FN and enhance cell attachment (Fig. S1). Because the FITC-SB method was more sensitive than the BO method, we rationalized that the plasma treatment may have been responsible for the findings. Thus, we evaluated the contribution of plasma treatment to the TJ-function sensitivity of the BO method. We hypothesized that plasma treatment was a significant factor between the two methods, such that the BO method with O2-plasma treatment would be more similar to the FITC-SB method. We compared permeability (stained areas) for the BO method with (Fig 2 gray bars) and without O2-plasma treatment (Fig. 2 white bars), and the FITC-SB method (Fig. 2 black bars) for three conditions: 0% ΔSA with VC, 0% ΔSA with AMA, and 37% ΔSA with VC. In contrast to our hypothesis, BO with O2-plasma treatment did not reveal significant increases in permeability above 0% ΔSA with VC for either the stretch or AMA treatment (i.e. no asterisks on gray bars in Fig. 2 or in Table S1). Given our evidence (Fig S1) that O2-plasma treatment results in a more uniform fibronectin distribution, we speculate that this enhanced fibronectin distribution may contribute to a decreased exposure of the BO to the basolateral cell surface of monolayers on treated membranes. We conclude that, in contrast to our hypothesis, O2-plasma treatment actually decreases the sensitivity of the BO method, resulting in more disparate results from the FITC-SB method. However, the O2-plasma treatment produces the required hydrophilic conditions for the FITC-SB method, and induces a more even distribution of fluorescently tagged fibronectin under the monolayer (Fig. S1).

Cell death and local permeability

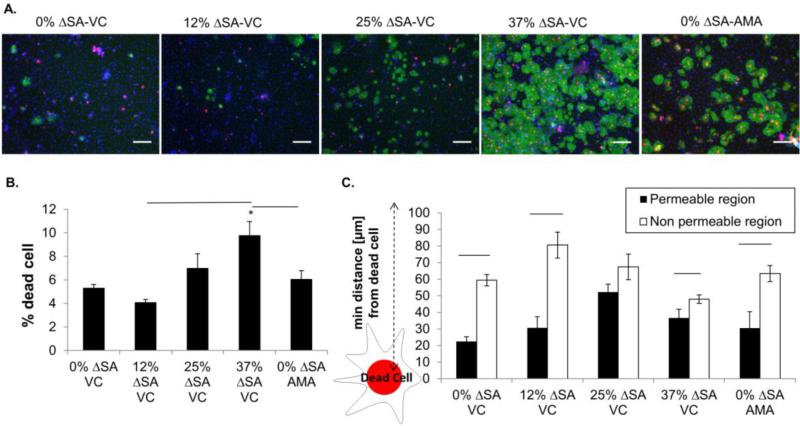

Stretch associated monolayer RAEC death for the FITC-SB method was consistent with our previously published values (Fig 3A red-stained nuclei, Fig 3B)(35), and AMA treatment was not associated with increased cell death. Furthermore, Pearson's correlation analysis showed strong positive correlation (correlation coefficient =0.7908, p<.0001) between quantity of cell death and the amount of FITC-SB monolayer staining. In the triple-stained images, qualitatively we observed most damaged cells were in FITC-SB stained areas, especially at 37% ΔSA with VC (Fig. 3A). We hypothesized that permeability increases related to the distribution of dead cells, not just the number or density of dead cells in a region. Therefore, our hypothesis was that the proximity of living cells to dead cells would be greater in permeable regions (i.e. distances would be smaller). To evaluate our hypothesis quantitatively, we evaluated the calculated the distance between each live cell and their closest damaged cell neighbor, and compared average “closest neighbor” distance calculated for the permeable (FITC-positive, Fig 3C black bars) regions to those in the non-permeable (FITC-negative, Fig 3C white bars) regions. The calculated minimum neighbor distance between live and damaged cells was significantly shorter in the permeable regions than the impermeable regions for each experimental condition, except 25% ΔSA (Fig.3C). Therefore, we conclude that permeable, or FITC-SB staining, is characterized by live cells in close proximity to damaged cells (even in unstretched monolayers), compared to the impermeable regions.

Figure 3. Monolayer cell death rates and nearest-neighbor distances between live cells and damaged cells.

A. Representative triple stained RAEC monolayers after 10 min of cyclic stretch or AMA treatment. Streptavidin-biotin stained permeable regions (FITC, green), nuclei of damaged cells (red, EtHD), and nuclei of all cells (blue, Hoescht) reveal higher stretch magnitudes results in more permeability and cell death. Bar = 100 μm. B. Percent damaged cells (relative to total number of adherent cells in the field) in stretched and AMA treated monolayers (n=5/group). C. Distance from live cells residing in permeable and non-permeable regions to nearest neighbor damaged cells. All values, mean±SEM. Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference from 0% ΔSA with VC; and bars indicates significant differences between groups. These images were enhanced after analysis to enhance visibility for publication.

Discussion

We have modified a method previously developed to measure permeability of endothelial cells plated on gelatin coated membranes (18) for use in pulmonary epithelial cells plated on fibronectin. In the modified FITC-SB method, we introduced O2-plasma treatment to ensure a uniform distribution of the fibronectin coating and enhance cell attachment, and used sulfo-NHS-LC-LC-biotin instead of the NHS-LC-LC-biotin used previously (18) to reduce the uptake of biotin by the cells. Moreover, we compared the sensitivity of the FITC-SB method to our previously published method using BO (6), and noted several important advantages of the new method. The first advantage is that the FITC-SB method is not affected by stretch. Specifically, BO binds to the Na+-K+ ATPase pumps on the basolateral surfaces of the RAECs, and we have documented that stretch increases the number of pumps at the membrane and/or pump activity (14, 20), which increases the potential for BO staining regardless of TJ integrity. Second, the FITC-SB method has a superior mechanistic advantage over the BO method. As the tight junction is disrupted during mechanical stretch (7, 11), intercellular gaps form (Fig. 4), increasing opportunities for BO and FITC-SB to bind, and creating a fluorescently stained region where barrier properties are compromised. However, BO binds to the exposed basolateral cell surfaces but not to cell-free denuded membrane regions, likely underestimating the actual permeable region in the monolayer. In contrast the FITC-SB binds only the exposed biotinylated membrane between cells and in cell-free regions (Fig. 4). Taken together, the FITC-SB method presented in this report is a more sensitive and specific method to detect barrier permeability due to TJ failure, cell rupture, and cell removal than the BO method.

We determined that RAECs located in permeable FITC-stained regions were closer to damaged cells than those in intact regions of the monolayer, and hypothesize that there is a link between locations of cell death and barrier property disruption. We speculate that this association may be due to a stiffness discontinuity in the monolayer between intact and damaged cells (27) creating stress concentrations that affect the local mechanical integrity of the monolayer and/or due to paracellular and intercellular signals initiated in the damaged and dying cells (24, 25, 29) that influence the biochemical equilibrium of the intact cells nearby.

In conclusion, we have introduced a more sensitive and specific method to assess stretch-induced permeability of epithelial cell monolayers, and have used the method to show that damaged cells play important roles in local disruption of barrier in epithelial cell monolayers.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Distribution of FITC-streptavidin-biotin on cell-free PDMS membranes with and without O2-plasma treatment. Representative images 5 minutes after 25ug/ml of FITC-streptavidin was added to biotin (40nM) labeled fibronectin coated PDMS membranes. Bars = 100 μm.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH R01-HL57204 and Stephenson fund of the University of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors (Song, Davis, Lawrence, and Margulies) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Standards

No human studies were conducted for this research. The animal was protocol approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC),

References

- 1.Aschauer L, Gruber LN, Pfaller W, Limonciel A, Athersuch TJ, Cavill R, Khan A, Gstraunthaler G, Grillari J, Grillari R, Hewitt P, Leonard MO, Wilmes A, Jennings P. Delineation of the key aspects in the regulation of epithelial monolayer formation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2013;33(13):2535–50. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01435-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borok Z, Danto SI, Zabski SM, Crandall ED. Defined medium for primary culture de novo of adult rat alveolar epithelial cells. In vitro cellular & developmental biology Animal. 1994;30A(2):99–104. doi: 10.1007/BF02631400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunzel N. Fundamentals of Urine and Body Fluid Analysis. Saunders; Philadelphia, PA.: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canfield PE, Geerdes AM, Molitoris BA. Effect of reversible ATP depletion on tight-junction integrity in LLC-PK1 cells. The American journal of physiology. 1991;261(6 Pt 2):F1038–45. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.261.6.F1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavanaugh KJ, Cohen TS, Margulies SS. Stretch increases alveolar epithelial permeability to uncharged micromolecules. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2006;290(4):C1179–88. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00355.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavanaugh KJ, Jr., Margulies SS. Measurement of stretch-induced loss of alveolar epithelial barrier integrity with a novel in vitro method. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2002;283(6):C1801–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00341.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavanaugh KJ, Jr., Oswari J, Margulies SS. Role of stretch on tight junction structure in alveolar epithelial cells. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2001;25(5):584–91. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.5.4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavanaugh KJ, Margulies SS. Measurement of stretch-induced loss of alveolar epithelial barrier integrity with a novel in vitro method. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2002;283(6):C1801–C8. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00341.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen W, Sharma R, Rizzo AN, Siegler JH, Garcia JG, Jacobson JR. Role of claudin-5 in the attenuation of murine acute lung injury by simvastatin. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2014;50(2):328–36. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0058OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen TS, Cavanaugh KJ, Margulies SS. Frequency and peak stretch magnitude affect alveolar epithelial permeability. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(4):854–61. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00141007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen TS, DiPaolo BC, Lawrence GG, Margulies SS. Sepsis enhances epithelial permeability with stretch in an actin dependent manner. PloS one. 2012;7(6):e38748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen TS, Gray Lawrence G, Margulies SS. Cultured alveolar epithelial cells from septic rats mimic in vivo septic lung. PloS one. 2010;5(6):e11322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danto SI, Zabski SM, Crandall ED. Reactivity of alveolar epithelial cells in primary culture with type I cell monoclonal antibodies. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 1992;6(3):296–306. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.3.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidovich N, DiPaolo BC, Lawrence GG, Chhour P, Yehya N, Margulies SS. Cyclic stretch-induced oxidative stress increases pulmonary alveolar epithelial permeability. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2013;49(1):156–64. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0252OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dipaolo BC, Davidovich N, Kazanietz MG, Margulies SS. Rac1 pathway mediates stretch response in pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2013;305(2):L141–53. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00298.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiPaolo BC, Margulies SS. Rho kinase signaling pathways during stretch in primary alveolar epithelia. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2012;302(10):L992–1002. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00175.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dos Santos CC, Slutsky AS. Invited review: mechanisms of ventilator-induced lung injury: a perspective. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2000;89(4):1645–55. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.4.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubrovskyi O, Birukova AA, Birukov KG. Measurement of local permeability at subcellular level in cell models of agonist- and ventilator-induced lung injury. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2013;93(2):254–63. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang X, Neyrinck AP, Matthay MA, Lee JW. Allogeneic human mesenchymal stem cells restore epithelial protein permeability in cultured human alveolar type II cells by secretion of angiopoietin-1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285(34):26211–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher JL, Margulies SS. Na(+)-K(+)-ATPase activity in alveolar epithelial cells increases with cyclic stretch. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2002;283(4):L737–46. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00030.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imanaka H, Shimaoka M, Matsuura N, Nishimura M, Ohta N, Kiyono H. Ventilator-induced lung injury is associated with neutrophil infiltration, macrophage activation, and TGF-beta 1 mRNA upregulation in rat lungs. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2001;92(2):428–36. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200102000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacob AM, Gaver DP., 3rd Atelectrauma disrupts pulmonary epithelial barrier integrity and alters the distribution of tight junction proteins ZO-1 and claudin 4. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2012;113(9):1377–87. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01432.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jokinen V, Suvanto P, Franssila S. Oxygen and nitrogen plasma hydrophilization and hydrophobic recovery of polymers. Biomicrofluidics. 2012;6(1):16501–1650110. doi: 10.1063/1.3673251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krysko DV, Leybaert L, Vandenabeele P, D'Herde K. Gap junctions and the propagation of cell survival and cell death signals. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death. 2005;10(3):459–69. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-1875-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lieberthal W, Levine JS. Mechanisms of apoptosis and its potential role in renal tubular epithelial cell injury. The American journal of physiology. 1996;271(3 Pt 2):F477–88. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.3.F477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell LA, Overgaard CE, Ward C, Margulies SS, Koval M. Differential effects of claudin-3 and claudin-4 on alveolar epithelial barrier function. American journal of physiology Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2011;301(1):L40–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00299.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikolaev NI, Muller T, Williams DJ, Liu Y. Changes in the stiffness of human mesenchymal stem cells with the progress of cell death as measured by atomic force microscopy. Journal of biomechanics. 2014;47(3):625–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oshima T, Gedda K, Koseki J, Chen X, Husmark J, Watari J, Miwa H, Pierrou S. Establishment of esophageal-like non-keratinized stratified epithelium using normal human bronchial epithelial cells. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2011;300(6):C1422–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00376.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenblatt J, Raff MC, Cramer LP. An epithelial cell destined for apoptosis signals its neighbors to extrude it by an actin- and myosin-dependent mechanism. Current biology : CB. 2001;11(23):1847–57. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strengert M, Knaus UG. Analysis of epithelial barrier integrity in polarized lung epithelial cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;763:195–206. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-191-8_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suki B, Hubmayr R. Epithelial and endothelial damage induced by mechanical ventilation modes. Current opinion in critical care. 2014;20(1):17–24. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan SH, Nguyen NT, Chua YC, Kang TG. Oxygen plasma treatment for reducing hydrophobicity of a sealed polydimethylsiloxane microchannel. Biomicrofluidics. 2010;4(3):32204. doi: 10.1063/1.3466882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tremblay LN, Slutsky AS. Ventilator-induced lung injury: from the bench to the bedside. Intensive care medicine. 2006;32(1):24–33. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2817-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tschumperlin DJ, Margulies SS. Equibiaxial deformation-induced injury of alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. The American journal of physiology. 1998;275(6 Pt 1):L1173–83. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.6.L1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tschumperlin DJ, Oswari J, Margulies AS. Deformation-induced injury of alveolar epithelial cells. Effect of frequency, duration, and amplitude. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(2 Pt 1):357–62. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9807003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Sun B, Ziemer KS, Barabino GA, Carrier RL. Chemical and physical modifications to poly(dimethylsiloxane) surfaces affect adhesion of Caco-2 cells. Journal of biomedical materials research Part A. 2010;93(4):1260–71. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yehya N, Yerrapureddy A, Tobias J, Margulies SS. MicroRNA modulate alveolar epithelial response to cyclic stretch. BMC genomics. 2012;13:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Distribution of FITC-streptavidin-biotin on cell-free PDMS membranes with and without O2-plasma treatment. Representative images 5 minutes after 25ug/ml of FITC-streptavidin was added to biotin (40nM) labeled fibronectin coated PDMS membranes. Bars = 100 μm.