Abstract

Objective

We address cancer communication by creating and assessing the impacts of a theatrical production, When Cancer Calls…(WCC…), anchored in conversations from the first natural history of a patient and family members talking through cancer on the telephone.

Methods

A national study was conducted using a multi-site and randomized controlled trial. An 80-minute video was produced to assess viewing impacts across cancer patients, survivors, and family members. Comparisons were made with a control video on cancer nutrition and diet. Pretest-posttest sample size was 1006, and 669 participants completed a 30-day follow-up impacts assessment.

Results

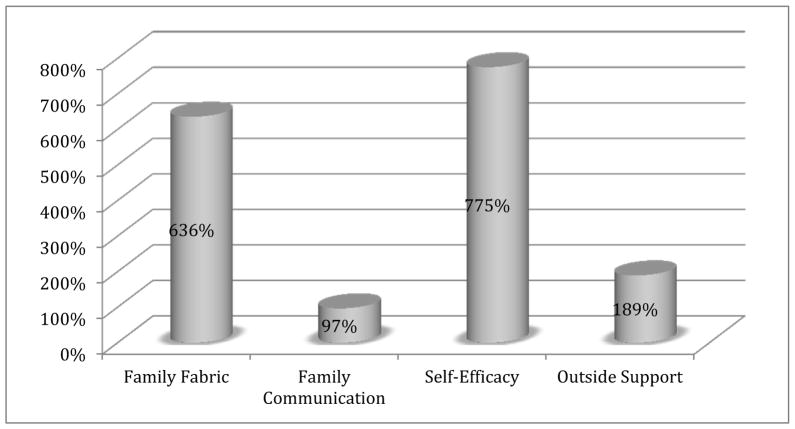

All five family and communication indices increased significantly for WCC…. When compared to the placebo, average pretest-posttest change scores were higher for self-efficacy (775%), family fabric (665%), outside support (189%), and family communication (97%). One month following viewings, WCC… participants reported 30% more conversations about cancer among patients and family members about cancer.

Conclusion

A new genre of Entertainment-Education (E-E) was created that triggers positive reactions from audience members. Managing delicate and often complex communication about the trials, tribulations, hopes, and triumphs of cancer journeys is fundamentally important for everyday living.

Practice Implications

Unique opportunities exist to make WCC… available to national and global audiences, create tailored curricula, and integrate these viewings into educational programs for patients, family members, and care-provider teams.

Keywords: Communication and cancer, conversation analysis, family cancer journeys, entertainment-education, health communication interventions, randomized trials, When Cancer Calls…

1. Introduction

Over a decade ago, Singhal and Rogers (2002) identified important theoretical underpinnings of entertainment-education (E-E), “the intentional placement of educational content in entertainment messages” (p. 119). Specific attention was drawn to how more effective interventions might be designed by “adding the lustre of entertainment to the relatively ‘duller’ fields of health promotion, education, and development” (p. 120). The challenge for health communication researchers involves making critical decisions about how to access everyday lives of ordinary people, transforming these routine experiences into entertaining formats, and implementing effective strategies for educating community members about the fundamental importance of communication when managing diverse health issues. Successful E-E campaigns provide new insights about communication that create the potential for sustained behavioral change evidenced through improved health practices (Singhal & Rogers, 1999; Beach, Buller, & Dozier et al., 2014).

In this study we report national findings from a multi-city, randomized controlled trial designed to assess the impacts of a unique and powerful E-E intervention entitled When Cancer Calls… (WCC…). This 80 minute professional theatrical production, consisting of verbatim dialogue from actual family telephone conversations, addresses a major social problem in contemporary society: Communicating about cancer, from diagnosis through death of a loved one. Below we 1) provide a background describing how and why WCC… was created, 2) review the extant E-E literature, and provide a theoretical rationale that embodies the need for a new genre of E-E, 3) summarize previously reported feasibility (Phase I) findings, 4) describe our research methods and primary questions for the national (Phase II) project, 5) report results from audience members’ reactions during the recently completed national trial, and 6) raise important implications for the research and design of effective intervention strategies for educating a diverse public about communication throughout cancer journeys.

2. Using When Cancer Calls… to Trigger Meaningful Conversations about Cancer

An earlier research investigation generated basic conversation analytic findings of how a patient (mother/wife/sister) and family members talk through cancer on the telephone (Beach, 2009). Attention was drawn to how ordinary conversations are key resources for navigating the trials, tribulations, hopes, and triumphs of a real cancer journey. These phone calls, comprised of 61 phone calls over 13 months, represent the first natural history and collection of such interactions in the social and medical sciences. An extraordinary opportunity thus existed to make these conversations available to a diverse public whose lives have somehow been impacted by cancer. Because 3 out of 4 Americans’ lives have been directly and indirectly impacted by cancer (American Cancer Society, 2013), we sought to assess educational impacts on cancer patients, survivors, and family members about communication throughout cancer journeys.

Using these phone calls and transcriptions as a resource, a script was developed that is comprised of verbatim dialogue from naturally occurring phone conversations. WCC… (Figure 1) can be viewed live or through DVD screenings, and conveys important educational messages about how one family relied on communication when coming to grips with and facing cancer together on a daily basis.

Figure 1.

The WCC… logo.

The exceptional power of the arts was harnessed as an innovative learning tool for extending empirical research, exploring ordinary family life, and exposing often-misunderstood conceptions of cancer, health, and illness. By integrating the social sciences and the arts, education and entertainment (see Beach, Buller, & Dozier et al., 2014; Duque et al., 2008; Harris et al., 2009; Learning Center, 2006; Sherman & Simonton, 2001; Slater, 2002), we developed a narrative resource that triggers meaningful dialogue about delicate and often complex communication challenges arising from a longitudinal examination of cancer diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

By watching WCC… it also becomes possible to address often taken-for-granted and avoided cancer issues (Learning Center, 2006; Sherman & Simonton, 2001). Diverse human emotions are laid bare, meaningful insights about communication capture the attention of audience members, and key implications can be raised for further education. Existing healthy behaviors can be reinforced and viable new practices can be designed to improve social relationships in the midst of cancer.

3. Entertainment-Education (E-E) as a Creative Resource for Addressing Health

E-E is an innovative strategy for promoting public health awareness and prevention (Jack, 2010; Kreuter et al., 2007; Slater & Rouner, 2002). Diverse and often difficult-to-access populations can be impacted through alternative entertainment formats such as film, TV programs, theatre, informational videos, and video games (Duque et al., 2008; Kreuter, Holmes, & Alcaraz et al., 2010; McGregor, 2003). A wide range of important health topics have been addressed through film and TV, including excessive drinking (Guiding Light/CBS), diabetes (Amarte AsÍ/Telemundo), kidney disease (George Lopez/ABC), HIV and pregnancy (Without A Trace/CBS), liver disease (Scrubs/NBC), drug abuse (Huff/Showtime), amputees (Days of Our Lives/NBC), heart transplants and failures (Numb3rs/CBS; Albert, Buchsbaum, & Li, 2007), emotional eating and weight loss (George Lopez/ABC). Theatre or drama has also been used across related health education fields such as teen smoking prevention (Starkey & Orme, 2001), HIV/AIDS prevention education (Watts, 1998), and sexual education in grade schools (Blakey & Pullen, 1991).

3.1 Television and Theatrical Productions Focusing on Cancer

Various television and theatre programs assist patients and family members in dealing with cancer (Bugge, Helseth, & Darbyshire, 2009). One primary example is the Entertainment and Education Program (2003) developed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), a collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the Hollywood, Health, and Society (HH&S) program at USC’s Norman Lear Center (NCI News, 2011). Particular attention is paid to TV programming and workshops designed to refine writers’ and producers’ skills.

Some of the most effective films and TV programs promoting cancer education have included The Big C (Showtime), “Lucinda’s Breast Cancer” (As the World Turns/CBS), “BRCA – Breast Cancer Risks,” ER (NBC), and “Breast and Ovarian Cancer Expectations,” (Grey’s Anatomy/ABC). Related documentary films examine five families managing often life-changing consequences of pediatric cancer (Harter & Hayward, 2010), and how communication shifts from homes to clinics as patients are diagnosed with breast, gastrointestinal, head and neck cancer (Beach & Powell, 2015).

Various theatrical innovations have been created. The UK’s Cancer Tales (2009), based on transcribed interviews from five women about their cancer journeys, has also been developed into a workbook for facing challenging cancer circumstances (Hay et al., 2009; Levin et al., 2010). Several health, cancer centers, and community affiliations promote cancer education, including a focus on colorectal and cervical cancer at the Baylor College of Medicine, the dissemination of Catchitearly (2010) by the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center of Tennessee, and the Aracali Theater Project at San Francisco General Hospital with performances such as “Touched by cancer: Humoring the tumor” (2007).

Over 800 African American men and women viewed Stealing Clouds (2011), a production that significantly enhanced knowledge and involvement about breast cancer education and prevention (Livingston et al, 2009). Relationships between cancer and sensitive cultural issues, such as racism and sexism, have also been portrayed in the one-woman Breast Cancer Plays (2010). Programs for children exist such as the UK’s Theatre in Education (TiE, 2011). Surreal and humorous experiences with cancer are presented in How My Mother Died of Cancer (2010), Other Bedtime Stories and How I Spent my Cancer Vacation (Zoglin, 1996). Even musical revues, such as Cancer Queens (2010), have been created to expose a wide range of important cancer issues.

To summarize, TV and theatre productions focusing on cancer education have relied on three primary strategies for constructing audience messages: 1) enhancing writers’ and producers’ abilities to portray how cancer functions in everyday life; 2) testimonies, anecdotes, and role-plays from survivors revealing their personal experiences with cancer; and 3) interviews with persons whose lives have somehow been impacted by cancer as the basis for documentary films and theatrical productions.

3.2 Everyday Language Performance: A New Genre of Entertainment-Education (E-E)

Relying on naturally occurring conversations recorded by an actual family undergoing cancer, WCC provides a new genre of everyday language performance (Gray & van Oosting, 1996; Hopper, 1993; Stucky, 1993, 1998; Stucky & Glenn, 1993). Historically, research on the effectiveness of E-E campaigns has shown that the ability to transport audience members into narratives enhances persuasive effects (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986; Singhal & Rogers, 1999, 2002; Green & Brock, 2000, 2002). The greater “recipient’s sympathetic response to the character’s own development and experiences” (Slater & Rounder, 2002, p. 177), the more likely recipients are to accept E-E messages which shift their values and beliefs (Green, 2006; Petraglia, 2007).

4. Overview of the Phase I Feasibility (Pilot) Study

In a previously reported Phase I/Feasibility (pilot) study (Beach, Buller, & Dozier et al., 2014; Beach, Gutzmer, & Dozier, 2014; Beach, Gutzmer, & Dozier, in press) live and DVD recordings were shown to a total of 204 cancer patients, family members, and medical professionals in San Diego and Denver. Pre- and post-performance questionnaires were administered to solicit audience feedback. Pre/post change scores demonstrated positive changes in opinions about the perceived importance, and attributed significance, of family communication in the midst of cancer. For example, following the performances and screenings: 89% agreed their interest was held from beginning to end and considered the dialogue appropriate for “people like me;” 74% indicated that the story told was uplifting and inspiring; and only 10% considered these events “too depressing,” despite the impending death of the cancer patient.

5. Methods from Phase II National Dissemination and Effectiveness Trial

A multi-site and group randomized, pretest-posttest controlled experimental design was conducted to evaluate the effects of the WCC…video on family communication about cancer.

5.1 Participants and Recruitment Procedures

Regionally diverse samples of adults were enrolled at four sites: San Diego, CA; Salt Lake City, UT; Lincoln, NE; and Boston, MA. Participants were required to be over the age of 18 and have the ability to read and speak English. In San Diego, participants who had seen the live performance used to create the video were excluded from the trial.

Local hosts affiliated with a hospital, two universities, and a comprehensive cancer center recruited samples through newspaper advertisements, online advertising, community organizations, and site-specific cancer centers. Interested participants called a local telephone number or visited an online portal to register. Prospective participants were screened for eligibility and instructed to choose one of two available dates to attend a video screening. An initial target sample size of 1,200 participants, approximately 300 at each of the four sites, was designed to yield a power of 0.80. A total of 1006 participants (84%) were accrued for the pretest-posttest sample, and 669 of these participants also completed a 30-day follow-up impacts assessment.

All participants provided informed consent. Consent and study procedures were approved by the local institutional review boards (IRBs) at the authors’ institutions and at each study site. Participants were provided $50 for attending the video screenings and completing the pretest and posttest questionnaires. Participants who completed the 30-day follow-up questionnaire in the allotted time were entered into a drawing for a $200 Amazon gift card.

5.3 Intervention Video Production: When Cancer Calls…

In spring 2013, a live performance of WCC… was video recorded at a community theatre before a live audience of 250 people. Professional film-makers used multiple microphones and four video cameras to capture the performance. On-site digital editing and professional digital post-production editing by the university’s media production center yielded an 80-minute, high-quality intervention video for the randomized trial.

Primary characters involve the mom (cancer patient), dad, son, aunt (mom’s sister), gramma (dad’s mom), son’s ex-wife, airline representatives, and son’s girlfriend. A professor/narrator guides viewers through major scenes: the initial delivery and receipt of bad cancer news; decisions about no life support; son’s calls to the airlines in search of ‘compassion fares’; living in the midst of cancer ambiguities and crises; commiserating about the fears of cancer; telling humorous stories about topics such as dogs, mom’s hair loss, and gramma’s dusting cloths; reflecting on how a family cancer journey changes one’s philosophy of living; and final calls about mom’s death, which occurred two hours following the last recorded call. Throughout, dialogue reveals how bad news is balanced with good and hopeful possibilities for a bright future.

5.4 Control Video Selection: Fighting Cancer With Your Fork

A 57-minute control video was selected as an attention-control, consisting of a recorded lecture about nutrition and dietary choices to prevent and control cancer. The 2008 lecture featured a director of nutrition services at a local NIH-designated comprehensive cancer center.

This lecture met the project’s criteria of being a video recording providing valuable information on cancer prevention, and providing important content that could impact audiences. But it did not explicitly address communication with patients or family members. In this way, all participants had a video viewing experience, we could experimentally manipulate the presence or absence of just patient and family communication, and possible Hawthorne effects were controlled (i.e., positive responses on post measures merely because one was observed watching a video on cancer prevention).

5.5 Trial Procedures

Each site hosted two video screenings, on consecutive dates, for the intervention and control videos. Participants arrived at the auditorium, checked in with research staff, completed the consent form and pretest questionnaire, and were seated. Participants and research staff were blinded to the order of video selection, randomized by using the SAS PROC PLAN statement. On the first date at each host site, five minutes prior to screenings, research team members opened a sealed envelope containing the experimental condition assignment. This randomly selected video was shown to the audience. The alternative treatment video was shown for the next screening event. Audience members completed the posttest survey immediately after viewing each assigned video.

Facilitated talkback sessions (large focus groups) followed the completion of the posttest questionnaires after each video screening. Audience members who chose to stay were invited to provide verbal reactions to the videos and others’ comments (see Beach, Moran, & Dozier et al., 2015). Facilitators were local communication and psychology professionals.

Thirty days after the treatment, participants were re-contacted and invited to complete the 30-day follow-up questionnaire. Those that provided email addresses (966/96%) when enrolling received an email invitation and a link to complete an online questionnaire. Participants that did not provide email addresses (40/4%) were sent a paper version of the same questionnaire with a return-addressed, stamped envelope. Weekly reminder emails or postcards were sent to participants who did not complete the questionnaire within three weeks. Four weeks following the initial invitation, participants who had not completed the questionnaire were called by a research assistant and asked to complete the questionnaire over the telephone. A breakdown of the number of participants by sites is provided in Table 1, including the subsample participating in the 30-day follow-up.

Table 1.

Participants By Sites for Pretest/Posttest and 30-day Follow-up Measures

| Site | Sample | When Cancer Calls… | Placebo | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Diego | Pre/Post | 196 | 204 | 400 |

| 30-Day | 115 | 129 | 244 | |

| Salt Lake City | Pre/Post | 103 | 161 | 264 |

| 30-Day | 68 | 111 | 179 | |

| Lincoln | Pre/Post | 61 | 48 | 109 |

| 30-Day | 49 | 35 | 84 | |

| Boston | Pre/Post | 123 | 110 | 233 |

| 30-Day | 82 | 80 | 162 | |

| Totals | Pre/Post | 483 | 523 | 1006 |

| 30-Day | 314 | 355 | 669 |

5.6 Measures

In the pilot study for this project, measures were developed inductively from conversation analytic investigations of the original audio recorded phone calls (Beach, 2009). Exploratory factor analysis yielded five indices (Beach, M. K. Buller, Dozier, D. B. Buller, & Gutzmer, 2014). In the present study, confirmatory factor analysis was used on the pilot indices, yielding single factor structures for each index. These indices, descriptions, and pretest/posttest alphas are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cronbach’s Alphas for Pretest and Posttest Indices

| Index | Description | Pretest | Posttest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Fabric | Talk about topics such as cars, dogs, and food, and actions such as humor and teasing, are important cancer journey resources | .60 | .74 |

| Family Communication | Open communication strengthens bonding, care, and reduction of uncertainty | .75 | .79 |

| Self-Efficacy | Confidence and ability to talk with family about cancer | .60 | .69 |

| Emotional Support | Importance of support, commiseration, and compassion | .79 | .81 |

| Outsider Support | Importance of talking with others outside nuclear family about cancer journey | .69 | .76 |

The pretest also included eight items on nutrition to assess content in the control video, six demographic questions, and seven items on the quality of family relationships as reported by cancer patients and survivors.

The immediate posttest included seven items measuring participants’ evaluations of the video they watched. The 30-day follow-up consisted of one item on the frequency of family communication about cancer. During the live performance of WCC…, consenting audience members (N=75) participated in a pilot test of the pretest, posttest and 30-day follow-up questionnaires. No specific problems were identified (e.g., ambiguities about particular questions or questionnaire format).

6. Results

Data analysis was conducted in four phases. First, pretest and posttest means for the five indices were computed separately for the experimental treatment (WCC…) and the placebo. Second, difference scores (difference = posttest - pretest) were computed for all indices. Third, difference scores were tested, using treatment vs. placebo as the independent variable. Fourth, the number of family conversations about cancer (measured in the 30-day follow-up questionnaire) was tested for differences between WCC… and the placebo. Two-tailed alpha criteria was set at p=.05 for all tests.

Participants’ age ranged from 18 to 91 years (M = 31.3, SD = 16.3). Regarding gender, 69% were women, 30% were men, and 1% declined to state. A large majority of participants had lost family or friends to cancer, and a majority of participants were White (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cancer Status and Ethnicity of Participants (all sites)1

| Cancer Status | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Lost Family/Friend To Cancer | 59% |

| Family/Friend Cancer Survivor | 33% |

| Family/Friend With Cancer | 32% |

| Cancer Survivor | 9% |

| Current Cancer Patient | 5% |

| Ethnicity | |

| African American | 5% |

| Other non-white | 7% |

| Asian American | 13% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 15% |

| White | 75% |

Participants permitted to provide multiple responses to ethnicity and cancer status; totals exceed 100%.

Regarding attendance, 34% attended the screenings alone, 41% attended with one other person, 13% with two other people, and 11% attended with three or more people. Number of people attending in a group, ranging from “by myself” (1) to “with three or more” (4) was not significantly correlated with pretest, posttest, or change scores for any of the five indices. The number of people attending together was negatively but not significantly correlated with the number of family conversations about cancer during the 30 days subsequent to exposure to either WCC… or the placebo treatment, r (657) = −.05, p = .18.

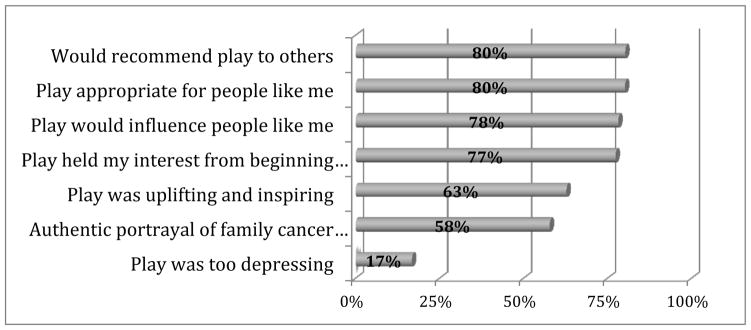

As summarized in Figure 2, audience reactions to WCC… were very positive. Four out of five reported they would recommend the performance to others and the communication they observed was “appropriate for people like me.” Over three-quarters of participants exposed to WCC… said the performance held their interest from beginning to end and would “influence people like me.” Only 17% indicated that the performance was “too depressing”.

Figure 2.

Audience evaluations of When Cancer Calls… (all sites).

As in the Phase I pilot study, all five indices increased significantly from pretest to posttest for participants exposed to the experimental treatment (Table 4). However, three of the five indices also increased significantly for participants exposed to the placebo treatment. These were the indices for family fabric, family communication, and outside support. This indicates a significant placebo effect for these three indices. The self-efficacy index did not increase significantly, and the emotional support index decreased from pretest to posttest for the placebo participants.

Table 4.

Differences in Pretest/Posttest Means for Treatment and Placebo Participants (all sites)

| Pretest | Posttest | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| When Cancer Calls… | M | S.D. | M | S.D. | t | d.f. | p |

| Family Fabric | 6.98 | 1.05 | 8.01 | 0.87 | 23.22 | 470 | <.001 |

| Family Communication | 7.52 | 1.15 | 8.10 | 0.85 | 12.97 | 468 | <.001 |

| Self-Efficacy | 8.07 | 1.00 | 8.43 | 0.74 | 8.98 | 472 | <.001 |

| Emotional Support | 8.07 | 0.93 | 8.34 | 0.72 | 8.33 | 464 | <.001 |

| Outside Support | 7.72 | 1.16 | 8.27 | 0.86 | 11.97 | 472 | <.001 |

| Pretest | Posttest | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Placebo | M | S.D. | M | S.D. | t | d.f. | p |

| Family Fabric | 7.12 | 0.97 | 7.26 | 1.06 | 3.30 | 478 | .001 |

| Family Communication | 7.52 | 0.99 | 7.82 | 1.02 | 7.00 | 487 | <.001 |

| Self-Efficacy | 8.09 | 0.86 | 8.12 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 495 | .319 |

| Emotional Support | 8.03 | 0.86 | 7.99 | 1.02 | 1.09 | 491 | .276 |

| Outside Support | 7.70 | 1.13 | 7.89 | 1.19 | 4.64 | 510 | <.001 |

Analysis of variance was used to test the significance and effect size of the change caused by the two treatments. For all five indices, average change scores for participants exposed to WCC… were significantly higher than average change scores for those exposed to the placebo. This indicates that WCC… produced considerably greater impacts for family relations and communication (Table 5).

Table 5.

Change Scores for Treatment and Placebo Participants (all sites)

| Treatment | Placebo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Indices | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | d.f. | F-ratio | p | η2 |

| Family Fabric | 1.03 | 0.96 | 0.14 | 0.92 | 1, 948 | 211.84 | <.001 | .183 |

| Family Communication | 0.59 | 0.98 | 0.30 | 0.95 | 1, 955 | 21.42 | <.001 | .022 |

| Self-Efficacy | 0.35 | 0.85 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 1, 967 | 35.26 | <.001 | .035 |

| Emotional Support | 0.27 | 0.69 | −0.03 | 0.67 | 1, 955 | 46.35 | <.001 | .046 |

| Outside Support | 0.55 | 1.00 | 0.19 | 0.95 | 1, 982 | 32.68 | <.001 | .032 |

Framed as percentages (where a tie with the placebo equals zero percent), compared with the placebo, WCC… produced greater impacts on family communication (97%) and outside support (189%). Strikingly, viewers of WCC… also reported a 636% stronger reaction to moments when family fabric was communicated, and a 775% increase in self-efficacy.

In the 30-day follow-up questionnaire, participants were asked: “In the last 30 days, about how many times have you discussed your family’s cancer journey with other members of your family? Members of your family include anyone that you consider a member, whether related by blood/marriage or not.” Participants viewing WCC… reported an average of 3.29 (S.D. = 5.37) such conversations in the 30 days since exposure; participants viewing the placebo reported an average of 2.53 (S.D. = 6.46) conversations. When compared to the placebo, participants exposed to WCC… reported 30% more conversations with family members about their families’ cancer journeys. Using analysis of variance and a one-tailed test, the relationship is statistically significant, F (1, 659) = 2.69, p = .05, χ2 = .004, but the effect size is quite small.

7. Discussion

Naturally occurring conversations about cancer on the telephone provide unique experiential, educational, and research opportunities. Audience members do not take for granted but become highly engaged with the perceived realism of WCC… performances, transporting them into the storyline of a single families’ cancer journey (Green, 2004; Green & Brock, 2000, 2002; Green, Brock, & Kaufman, 2004). Though the power of individuals’ narratives is apparent (Petraglia, 2007), primary focus is given to real-time storytelling and a range of related activities (e.g., delivering and receiving good and bad news, commiserating, laughing and joking). From these and related social actions, cancer education can illuminate how those impacted by cancer actually make choices, confront challenges, and create hopeful resources for coping with emerging events. The potential to significantly reduce suffering, provide social support, promote healing outcomes, and enhance quality of living can thus become anchored in how real persons talk about and through cancer over time.

Throughout this national trial, significant and positive impacts of WCC… were empirically demonstrated across geographically and demographically diverse audience members. Chosen because of its important cancer content, it was expected that the placebo condition (i.e., cancer/diet) would be sufficient to produce modest effects on audiences yet, as noted previously, also mitigate positive responses on post-tests simply because important cancer issues were addressed. However, these effect sizes were significantly smaller when compared to participants that viewed WCC… and reported a) significantly higher change scores on five indices tested and validated during our Phase I pilot study (i.e., self-efficacy, family fabric, outside support, family communication), and b) engaging in 30% more conversations about their family’s cancer journey over the next 30 days. Increasing the confidence and ability to talk with family members about cancer is essential. Equally important is gaining enhanced appreciation for activities such as non-cancer stories (e.g., about cars, dogs and food), humor and teasing between family members, and the value of receiving emotional support from others. Actions such as bonding, commiseration, and compassion are also critical for improving cancer journeys.

7.1 Implications for Future Research and Intervention

This investigation provides a pragmatic, impactful and new genre for E-E health communication interventions and campaigns. Numerous implications exist for disseminating WCC… to larger national and global audiences. Live performances and DVD screenings can occur in homes, at places of employment (e.g., corporations and military), in hospitals and clinics, and throughout educational systems that focus on health, families, and communication in contemporary society. The Internet can become a portal to resources that supplement the WCC… experience. Reactions of audience members to WCC… can be used to pinpoint specific problems and needs for education. Innovative curricula can be developed, and programs can be created that continually make conversations about cancer a priority within families and across health/medical systems. Specific and tailored training programs can be developed for diverse educational purposes across the social and medical sciences. Health professionals can also integrate WCC… into educational goals and priorities reflective of unique organizational cultures and system priorities.

While this study is innovative because it is grounded in real talk, and has been extended to design and implement a national trial, there are also a series of methodological issues that require further discussion and refinement. For example, what are the best strategies and criteria for selecting intervention and placebo video recordings? How can bias be minimized in ways that do not favor one group over another? What alternatives exist for assessing longitudinal impacts and, over varying periods of time, continue to promote sustained and positive behavioral changes?

Importantly, we conclude from our quantitative analysis and talkback sessions that WCC… is extremely cathartic and catalytic. Viewings create openings for participants to raise delicate conversations about their shared cancer journeys – topics that would otherwise not be raised or discussed. However, communication about cancer may not always continue after these sessions, and other problems may arise, suggesting the need to devise strategies encouraging productive and continued conversations.

Ongoing work (Beach, Moran, & Dozier et al., 2015) also relies on audience members’ spoken reactions to reveal how (or if) audience members become transported into the storylines of the WCC… performance, various emotional reactions, and ways that WCC… connected with their own life-world experiences. Preliminary content-analytic findings from Phases I & II strongly suggest that audience members identify with these domains of social life in ways that could enhance their abilities to improve communication in the family and the clinic. For example, audience members repeatedly observed that family relationships can be strengthened as a consequence of facing difficult times together, citing how dad and son grew and became closer throughout mom’s diagnosis, treatment, and eventual death. Increased awareness about the basic importance of talking about cancer experiences, rather than continually remaining silent about the stressors of cancer (e.g., anger, uncertainty, caregiving burdens, financial and sexual frustrations), can also provide unique growth opportunities. One final example is revealing: While this particular family tended not to say “I love you” at the end of phone conversations, many audience members treated these endearing closings as noticeably absent. They reported new motivation to continue stating “I love you”, or to change their behaviors to state their love for others on a regular basis (even if others do not state “I love you” in return).

Greater benefits from WCC… will also accrue when viewings are made available for physicians and care provider teams. From Phase I findings that involved healthcare providers, and also from numerous audience members in Phase II employed in diverse health professions, it is clear from their focus group and ‘talkback’ responses that health experts can also benefit considerably from viewing WCC…. We are discovering that WCC… viewings have the potential to increase sensitivity to what patients, and their significant others, actually deal with outside the clinical setting as they navigate their way through cancer and cancer care. Any combination of patients, survivors, family members, providers, and care-provider teams can view WCC… together. These experiences will function as triggers for sharing lay/professional perspectives and potentially building partnerships to work toward coherent, hopeful, and fulfilling outcomes. Overall, WCC… viewings and discussions have provided compelling and humane testimonies about very real social circumstances. Authenticity, in turn, stimulates suspension of disbelief, identification with characters, and increases audience receptivity to new ideas and techniques for refining communication to improve quality of living and care.

Figure 3.

Change scores for WCC… expressed as percentage greater than baseline change scores for the placebo.1

1Emotional Support index not included because the change score was negative for the placebo treatment.

Highlights.

When Cancer Calls… is an innovative theatrical production

Drawn from the first natural history of actual family phone conversations

Significant national impacts for cancer patients, survivors, and family members

Powerful triggering device for addressing delicate and complex cancer topics

A new genre of Entertainment-Education for national and global education

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through Grant #’s CA144235-01/02 (W. Beach, PI)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albert NM, Buchsbaum R, Li Jianbo. Randomized study of the effect of video education on heart failure healthcare utilization, symptoms, and self-care behaviors. Patient Educ & Couns. 2007;69:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. [Last accessed March 16 2015];2013 at http//www.cancer.org.

- Araceli Theater. [Last accessed October 16, 2014];Araceli theater. at http://www.ucsf.edu/news/2007/06/7544/sfgh-cancer-patients-perform-original-theater-piece.

- BBW News Desk. [Last accessed October 28, 2014];How my mother died of cancer plays fringe NYC encore series. 2010 Sep 09; at http://www.broadwayworld.com/article/HOW_MY_MOTHER_DIED_OF_CANCER_Plays_FringeNYC_Encore_Series_9913_20100909.

- Beach WA. A natural history of family cancer: Interactional resources for managing illness. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Gutzmer K, Dozier D. Family conversations about in-home and hospice care: From discovery to creation of an effective health intervention and campaign. In: Wittenberg-Lyles E, Ferrell B, Goldsmith J, Smith T, Ragan S, Glajchen M, Handzo G, editors. Textbook of palliative care communication. New York: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Powell T. Communication, compassion, and cancer care. 2015 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Moran MB, Dozier DM, Buller MK, Gutzmer K, Parsloe S. When Cancer Calls… : Creating reality theatre about family cancer and implications for Entertainment-Education (E-E) 2015 Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Buller MK, Dozier D, Buller D, Gutzmer K. Conversations about Cancer (CAC): Assessing feasibility and audience impacts from viewing The cancer play. Health Comm. 2014;29:462–472. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2013.767874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach WA, Gutzmer K, Dozier D, Buller MK, Buller D. Conversations about Cancer (CAC): A global strategy for accessing naturally occurring family interactions. In: Kim DK, Singhal A, Kreps G, editors. Global health communication strategies in the 21st century: Design, implementation, and evaluation. Peter Lange Publishing Group; 2014. pp. 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Beach W, Moran MB, Dozier D, Gutzmer K, Buller M, Parsloe S. When cancer calls… : Creating reality theatre about family cancer and implications for entertainment-education (E-E) 2015 Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Blakey V, Pullen E. You don’t have to say you love me: An evaluation of drama-based sex education projects for schools. Health Ed Jour. 1991;50:161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Breast Cancer Plays. [Last accessed October 28 2014];Imani Revelations presents: Breast cancer plays. 2010 at http://www.rmcneal.com/breast-cancer-plays.html.

- Bugge KE, Helseth S, Darbyshire P. Parents’ experiences of a family support program when a parent has incurable cancer. Jour of Clin Nurs. 2009;18:3480–3488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancerqueens.net. Cancer queens: A cancer prevention musical revue. [Last accessed February 6th, 2010];2010 at http://cancerqueens.net/

- Cancer Tales. [Last accessed February 6, 2011];2009 at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V9_Ehsw72Lo.

- Catchitearly. Catch it early: Variety entertainment and cancer awareness. [Last accessed February 5th, 2010];2010 at http://catchitearly.org/about.

- Community Network for Cancer Prevention (CNCP) & Forum Theater. [Last accessed March 13, 2015];Baylor College of Medicine. 2015 at http://www.bcm.edu/forumtheater.

- Duque G, Fung S, Mallet L, Posel N, Fleiszer D. Learning while having fun: The use of video gaming to teach geriatric house calls to medical students. Journal of the Amer Geri Society. 2008;56:1328–1332. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray PH, Van Oosting J. Performance in life and theatre. Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Green MC. Narratives and cancer communication. Jour of Comm. 2006;56(Suppl 1):S163–S183. [Google Scholar]

- Green MC, Brock TC. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Jour of Pers and Soc Psych. 2000;79:701–721. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MC, Brock TC. In the mind’s eye: transportation-imagery model of narrative persuasion. In: Green MC, Strange JJ, Brock TC, editors. Narrative impact: Social and cognitive foundations. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 315–341. [Google Scholar]

- Green MC, Brock TC, Kaufman GF. Understanding media enjoyment: The role of transportation into narrative worlds. Comm Theory. 2004;14:311–327. [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, Bowen DJ, Badr H, Hannon P, Hay J, Sterba KR. Family communication during the cancer experience. Jour of Health Comm. 2009;14:76–84. doi: 10.1080/10810730902806844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter LM, Producer, Hayward C., Producer . The art of the possible. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Scripps College of Communication; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hay J, Shuk E, Zapolska J, Ostroff J, Lischewski J, Brady MS, Berwick M. Family communication patterns after melanoma diagnosis. Jour of Family Comm. 2009;9:209–232. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper R. Conversational dramatism: A symposium. Text and Perfor Quart. 1993;13:181–183. [Google Scholar]

- Jack M. The Independent. 2010. Jan 15, Edutainment: Is there a role for popular culture in education? [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter MW, Homes K, Alcaraz K, Kalesan B, Rath S, Richert M, McQueen A, Caito N, Robinson L, Clark EM. Comparing narrative and informational videos to increase mammography in low-income African American women. Patient Educ & Couns. 2010;81(suppl):S6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Learning center.org. [Last accessed April 11, 2011];Writers and producers honored for addressing medical and ethical issues in television storylines. 2006 at http://www.learcenter.org/images/event_uploads/Sentinel06Winners.pdf.

- Levin TT, Moreno B, Silvester W, Kissane DW. End-of-life communication in the intensive care unit. Gen Hosp Psych. 2010;32:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JN, Smith NP, Mills C, Singleton DM, Dacons-Brock K, Richardson R, Grant D, Craft H, Harewood K. Theater as a tool to educate African Americans about breast cancer. Jour of Canc Ed. 2009;24:297–300. doi: 10.1080/08858190902997274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor S. Information on video format can help patients with localized prostate cancer to be partners in decision making. Patient Educ & Couns. 2003;49:279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [Last accessed March 28, 2011];NCI News: Entertainment resources. at http://www.cancer.gov/newscenter/entertainment-overview.

- Petraglia J. Narrative intervention in behavior and public health. Jour of Health Comm. 2007;12:493–505. doi: 10.1080/10810730701441371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman AC, Simonton S. Coping with cancer in the family. The Family Jour. 2001;9:193–199. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal A, Rogers EM. Entertainment-education: A communication strategy for social change. Taylor & Francis; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal A, Rogers EM. A theoretical agenda for entertainment-education. Comm Theory. 2002;12:117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Slater M. Entertainment education and the persuasive impact of narratives. In: Green MC, Strange JJ, Brock TC, editors. Narrative impact: Social and cognitive foundations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 157–181. [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD, Rouner D. Entertainment-education and elaboration likelihood: Understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Comm Theory. 2002;12:173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Starkey F, Orme J. Evaluation of a primary school drug drama project: Methodological issues and key findings. Health Ed Res. 2001;16(5):609–622. doi: 10.1093/her/16.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [Last accessed March 28, 2011];Stealingclouds. at http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5594232.

- Stucky N. Toward an aesthetics of natural performance. Text and Perf Quar. 1993;13:168–180. [Google Scholar]

- Stucky N. Unnatural acts: Performing natural conversation. Liter in Perf. 1998;8:28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Stucky N, Glenn P. Invoking empirical muse: Conversation, performance, and pedagogy. Text and Perf Quary. 1993;13:192–196. [Google Scholar]

- Teachernet. [Last accessed March 28, 2011];Theater in education. at http://www.teachernet.gov.uk/teachingandlearning/library/theatreineducation.

- The Big C. [Last accessed March 15, 2015];Showtime. 2010 at http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1515193/

- UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center (Producer) Fighting cancer with your fork. 2008 [Online Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3cR8GMsyLxE.

- Watts J. Popular drama prompts interest in HIV in Japan. Lancet. 1998;352:1840. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79915-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoglin R. Theater: How I spent my cancer vacation. [Last accessed October 28, 2014];Time. 1996 Dec 02; at http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,985639,00.html.