Abstract

Objective

To describe the development, pilot testing, and dissemination of a psychosocial intervention addressing concerns of young breast cancer survivors (YBCS).

Methods

Intervention development included needs assessment with community organizations and interviews with YBCS. Based on evidence-based models of treatment, the intervention included tools for managing anxiety, fear of recurrence, tools for decision-making, and coping with sexuality/ relationship issues. After pilot testing in a university setting, the program was disseminated to two community clinical settings.

Results

The program has two distinct modules (anxiety management and relationships/sexuality) that were delivered in two sessions; however, due to attrition, an all day workshop evolved. An author constructed questionnaire was used for pre- and post-intervention evaluation. Post-treatment scores showed an average increase of 2.7 points on a 10 point scale for the first module, and a 2.3 point increase for the second module. Qualitative feedback surveys were also collected. The two community sites demonstrated similar gains among their participants.

Conclusions

The intervention satisfies an unmet need for YBCS and is a possible model of integrating psychosocial intervention with oncology care.

Practice Implications

This program developed standardized materials which can be disseminated to other organizations and potentially online for implementation within community settings.

Keywords: young breast cancer survivors, sexuality, fear of cancer recurrence, survivorship, quality of life, psychosocial intervention

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide. Annual incidence exceeds 1.3 million new cases globally and there are 232,000 new cases in the U.S. [1,2]. Earlier detection and more effective treatments have dramatically increased the number of breast cancer survivors (BCS), with over 3 million in the U.S. [3]. Of the new diagnoses each year, 11.4% of breast cancer cases are among younger women, defined here as those under 45 years of age [4]. Younger women surviving breast cancer face unique challenges. The disease interrupts and complicates many aspects of adult development, including intimate relationships, work and career, childbearing, child-rearing, and other roles that many women play during these years [5].

Younger women report significant psychosocial concerns, including cancer-related emotional distress and symptoms of depression [5, 6]. Fear of cancer recurrence and uncertainty about the future contribute to ongoing stress that must be managed for decades past the end of treatment [7, 8]. Many survivors also experience a sense of greater clarity about their core priorities and values as a result of cancer and seek to retain these positive gains [9]. Survivors receive multiple and, at times, conflicting recommendations for reducing the risk of cancer recurrence and have complex psychological needs. For young breast cancer survivors (YBCS), it is a daunting task to manage challenges to physical and psychological wellbeing, while creating an integrated plan of behaviors and attitudes that support healthy survivorship.

In addition, YBCS must cope with important changes in their lives and relationships. Breast cancer treatment can necessitate the delay or unexpected end of childbearing. Chemotherapy induces menopause in many women, and the 5-year course of tamoxifen for those with estrogen-sensitive tumors creates a long lapse in the possibility of pregnancy [6, 10] as well a host of menopausal symptoms including vaginal changes and alterations in libido. Fertility concerns are thus quite common, as are concerns related to sexual function, body image, and intimacy [6, 11].

Oncology and survivorship care rarely address these issues, leaving psychosocial needs unmet. Programs do exist [12,13], but many do not specifically address the needs of YBCS, and programming may be sporadic or not feasible as part of routine survivorship care. Sustainable programming is needed to address these concerns and to help women transition from treatment to healthy survivorship.

Prior literature supports the efficacy of psychosocial interventions with cancer patients and survivors in reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression and improving adjustment to life after cancer treatment [14]. We expected that a psychosocial program targeting concerns of young BCS would be useful and well-received.

This paper describes the development of the Life After Breast Cancer (LABC) intervention program, designed to address these common concerns and fill this gap in services with a unique program for YBCS. The LABC intervention is a brief psychosocial program that targets specific concerns of this population, including stress management, fear of recurrence, and sexuality and intimacy. It was developed based on engagement of key stakeholders, including the target audience of YBCS.

2. Methods

2.1 Programmatic setting

UCLA was one of seven organizations awarded funding through a CDC initiative (DP 11-1111) that focused on provision of services to young women diagnosed with breast cancer, including the development of resources to improve their overall quality of life. UCLA responded by proposing a program designed to enhance health and wellness of YBCS by (1) addressing unique gaps in services through a regionally refined listing of community resources; and (2) developing a psychosocial intervention program aimed at providing skills on coping with psychosocial issues. Development of the larger program identified areas of need for YBCS more generally and based on this information, the LABC psychosocial intervention program was developed.

2.1.1 Needs Assessment and Stakeholder Engagement

We conducted a two-level needs assessment with community organizations serving BCS in the greater Los Angeles area, and key informant interviews with YBCS to determine the goals and priorities of the overall project, as well as the intervention program development. The community-level needs assessment included interviews with 23 organizations to a) document existing services available to YBCS, b) determine which services were being utilized, and c) establish which additional services were needed. Additionally, partnerships were established and leveraged to assist in the overall program planning process. The common services provided were referrals to resources and provision of cancer-related information. Organizations reported that YBCS were most concerned about fatigue, fear of recurrence, and side effects of treatment. Secondary to those, cognitive changes after chemotherapy, psychological concerns, fertility, and return to work were also commonly reported.

The survivor-level needs assessment included 18 phone interviews with YBCS who were diagnosed before the age of 45 and who had completed active treatment. Their most commonly reported problems were fatigue, cognitive issues, and fear of recurrence. Further, they identified gaps in information on fertility options and issues related to intimacy after diagnosis. The interviews were supplemented by meetings with an Internal Advisory Committee, a Community Advisory Committee composed of representatives from community organizations, and a Patient Advisory Committee composed of YBCS.

2.1.2 Prioritization of Needs

This process identified many psychosocial needs for YBCS, but specifically noted two areas for which there were few existing resources (a) managing fear of recurrence and (b) navigating intimacy. YBCS reported that worries about preventing or experiencing a recurrence and problems related to re-engaging with intimacy (whether partnered or single) presented ongoing concerns, but were difficult to discuss and not easy to find tools to address. Additionally, YBCS expressed a strong need to connect with other YBCS who were experiencing the same issues and challenges. YBCS reported that existing community support services often targeted older women and that in support groups there was limited understanding of the unique issues they were facing. This unmet need led to the development of the LABC psychosocial intervention program whose goal was to bring YBCS together to address these concerns.

2.2 Development and Content of the LABC intervention program

The LABC intervention program goals were to (a) address the top priorities identified in the needs assessment, and (b) provide this in a group format that incorporated both support and skill-building. Drawing upon evidence-based models of treatment [15–17], we designed a workshop that provided psychoeducation, skill-building exercises, and discussion. Initially, the program was designed to span 6 weeks of 2-hour workshops; however, members of the Advisory Committees strongly suggested the program be briefer due to the work and family demands on young women. As such, the intervention was developed as a one-day 6-hour workshop or a two-day, 4-hour workshop focusing on tools for a) managing stress/uncertainty and fear of cancer recurrence, and b) navigating sexuality and intimacy after breast cancer.

Table 1 provides an overview of the content areas covered in the LABC intervention including tools for managing anxiety and feelings of vulnerability about recurrence, tools for decision-making about lifestyle behaviors, and knowledge and skills for managing sexuality and relationship issues.

Table 1.

LABC Intervention Content

| Session 1 | Key points | Skills |

|---|---|---|

| Survivorship Trajectory-Overview |

|

|

| Review of Stress Cycle |

|

|

| Discussion of Stress in the Context of Cancer Survivorship |

|

|

| Review of Vulnerability/Values Matrix |

|

|

| Reinforcing Values-Based Behaviors - Exercise |

|

|

| Healthy Goal Setting Plan |

|

|

| Conclusion Module 1 |

|

|

| Session 2 | ||

| Survivorship Trajectory – Sexuality & Intimacy |

|

|

| Multiple Facets of Sexuality & Intimacy |

|

|

| Priorities and Satisfaction |

|

|

| New Models of Sexuality and Intimacy |

|

|

| Intimate Partner Communication |

|

|

| Dating |

|

|

| Body Image |

|

|

| Getting Back to Sexual Activity |

|

|

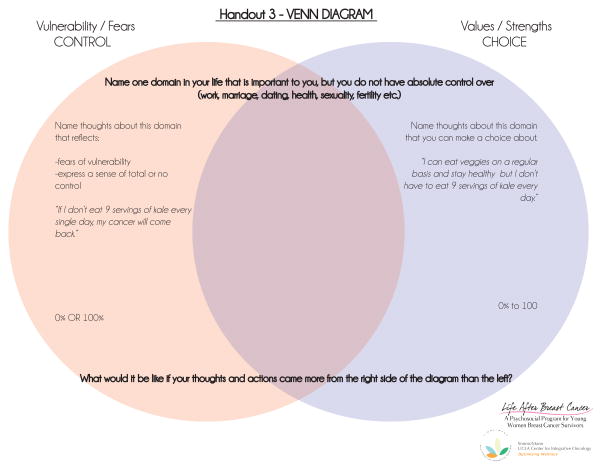

The intervention is broken into two sessions, both of which are accompanied by a workbook for each participant. Session 1 presents the phases and challenges associated with cancer survivorship. Each participant is asked to reflect on where she places herself in the overall cancer survivorship trajectory and to identify related stressors. Participants are led in discussions about the biological process of stress, the psychological aspects of stress, and how breast cancer survivorship triggers these stressors. The Vulnerabilities/Values Matrix (Figure 1) is introduced and serves as a core tool for consolidating awareness of thoughts and behaviors that reinforce feelings of vulnerability, uncertainty and loss of control or that can highlight strengths, clarity of priorities and wellbeing promoting choices. This tool facilitates an exercise that takes vulnerabilities and fears and changes them into values and strengths. The participants learn to identify domains in their life (i.e. diet, health, work, marriage, etc.) where they are vulnerable to thinking they don’t have control over it, which then generates fears. They are then given instruction on how to change the way they view that vulnerability and change it into a behavior they do have control over. The participants discuss ways to increase that control, thus transitioning fear into a strength. The discussion and exercises are deliberately meant to highlight the issue of lack of control/uncertainty for breast cancer survivors and provide them room to discuss the fear that comes with that awareness (the elephant in the room). This premise serves as a foundation for the rest of the workshop and provides a compelling entry into subsequent coping exercises in the workshop. The rest of the exercises, particularly the matrix, shift the focus away from need for absolute control/certainty which does not exist in any domain of their life, to focus on choices that are available to them based on their values/strengths rather than their fears/vulnerabilities.

Fig. 1.

The Vulnerabilities/Values Matrix

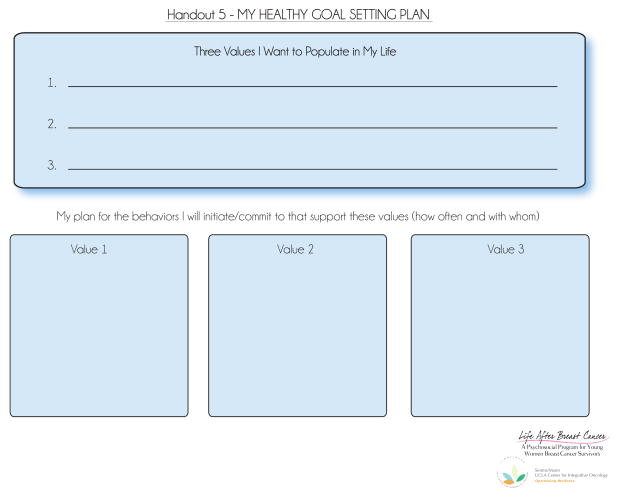

As participants become more aware of stressors and how to cope, they are guided through additional skill-building exercises that ask them to identify the values in their lives and the behaviors that facilitate these values. They are then asked to create a written plan to operationalize these values into behaviors (Figure 2). These concepts are reinforced in Session 2.

Fig. 2.

Written plan to operationalize values into behaviors.

Session 2 begins similarly with a review of the survivorship trajectory; however, it is focused on sexuality and intimacy. The team chose to devote the second session to this topic because it was identified as a large need, and because the first session fosters a sense of comfort for each group member to feel safe in sharing their personal thoughts on a sensitive subject. To start, participants are asked again to reflect upon where they place themselves along the survivorship trajectory with respect to sexuality and intimacy. Multiple facets of this content area are introduced (i.e. emotional, psychological, physical, relational, and spiritual) and the effect that breast cancer can have on these are discussed. The participants then identify the facets most affected in their own lives. The women are guided through self-reflection exercises where they rate the priority that sexuality and intimacy occupy in their lives and identify their current level of satisfaction with sexuality and intimacy. They are next asked to conceptualize their own models of sex that suit their own needs, which may not follow the “old model” of sexual response [17]. Next, a body image discussion takes place leading to ways to re-engage in sexual activity. This is followed by a psychoeducation discussion of contributors to lowered sexual desire, different forms of intimate activities other than intercourse, and resources for vaginal recuperation. Concluding this session, the participants are again asked to operationalize some of their values into behaviors with a goal set on how often they will try to exercise these behaviors in their everyday lives.

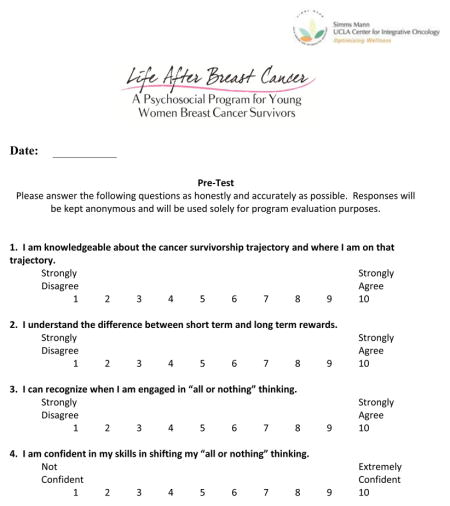

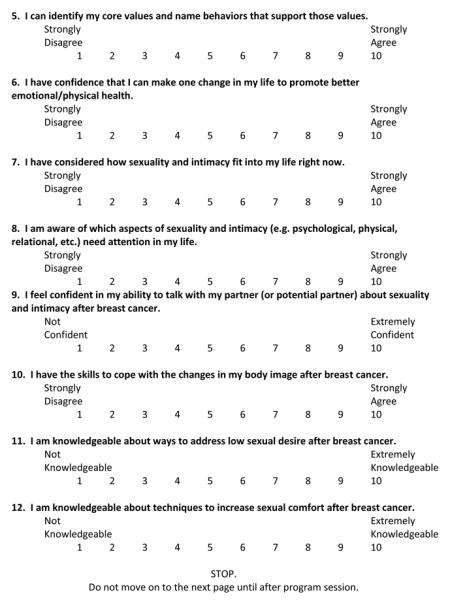

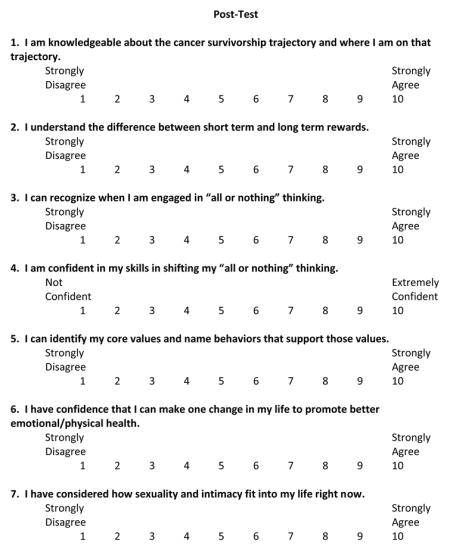

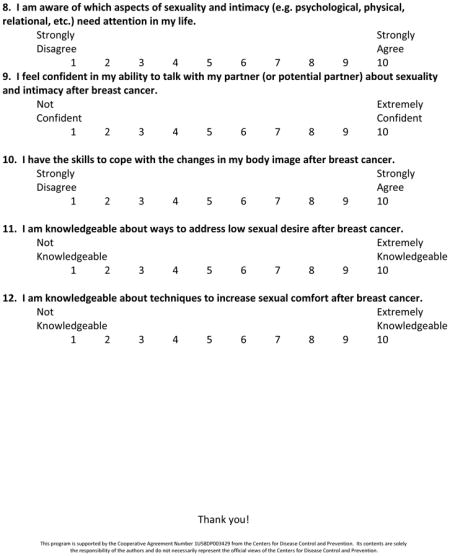

2.3 Evaluation of Intervention Program

An author-constructed 12-item questionnaire was developed to assess the impact of the intervention on the participants’ understanding of their experience as a cancer survivor, including understanding of their values, thinking about their situation, confidence in promoting better emotional and physical health, as well as various aspects of skills related to sexuality and intimacy, including body image, sexual desire and sexual comfort, all rated on a ten point scale with poles of “strongly disagree/strongly agree” or “not knowledgeable/extremely knowledgeable” or “not confident/extremely confident” (see questionnaire in Appendix). There were 6 items that reflected the first component (values/psychosocial well-being) of the intervention and 6 items that reflected the second component (relationships and intimacy) of the intervention. The questionnaire was administered before and after delivery of the intervention program to 5 separate groups of YBCS at 3 different institutions. We calculated a mean score for each component of the intervention at pre- and post-intervention to assess whether confidence and skills had changed as a result of the intervention. Additionally, an overall program evaluation with 5 point Likert scale items and comment sections was also administered at the conclusion of these workshops. These responses are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Feedback from LABC Workshop Evaluation Surveys.

| Feedback | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Themes | |||

| What is something you will take away from this program and use in your life? |

|

|

|

| What were the most positive aspects of the program? |

|

|

|

| What could be changed to make it a better program? |

|

|

|

3. Results

3.1 Participants and groups

YBCS were recruited from local community organizations, medical facilities, and through social media. Women were eligible if they were 45 years or younger at the time of diagnosis, and within 1 year of the end of initial cancer treatment, excluding hormonal therapy. We conducted 3 initial program workshops at UCLA to pilot the content and format of the intervention, and after this process it was finalized with a training manual. Two additional workshops were conducted at UCLA at which time clinicians from two community collaborating organizations observed the sessions so that they could implement the program at their facilities. Subsequently 2 workshop programs were conducted at one of the collaborating institutions, and 1 workshop was conducted at the other. Only limited demographic data were available for participants from UCLA, where the mean age was 41.7 years (median 43 years). Twenty-one women were <2 years post treatment, 7 women were <1 year post treatment, 5 women were <6 months post treatment, and 3 women had completed treatment more than 2 years prior. “Post treatment” was defined as having completed chemotherapy and/or radiation. Given the focus on program development, detailed demographic data were not collected at UCLA or the affiliated sites. Workshop group sizes ranged from 3 to 8 participants.

3.2 Pilot testing and Community Dissemination of the Intervention

The initial pilot-testing of the intervention occurred at UCLA and was conducted as two 4-hour sessions with two weeks in between. However, some women did not return for the second session and thus it was decided to conduct the subsequent pilot intervention groups in a single day as a 6-hour one-day seminar. Due to the length of the workshops, a light breakfast was provided for the 4-hour workshops, and breakfast and lunch were provided for 6-hour workshops. The co-facilitators (KA and EM) each delivered one-half of the intervention.

After the first two pilot groups at UCLA, an intervention manual was created that outlined and scripted each section of the workshop. The manual was pilot tested by using it to guide groups 3 and 4, and was revised according to facilitator experience, feedback from participants, and group facilitators from partner sites. This manual was used to train facilitators from the two community demonstration sites.

3.3 Participant assessment of the workshops

As this was an intervention development and dissemination project, we did not seek to do a formal assessment of participants and outcomes, and thus only a limited amount of data were collected to understand whether or not the content of the intervention targeted areas of need (as we had hypothesized) and whether participants noted improvements in skills and knowledge after participation in the intervention workshop. These assessments were conducted for the last two intervention programs at UCLA, and for each of the workshop programs at the community collaboration sites (two at one site and one at the other).

Pre- and post-test results indicated an overall gain in self-reported levels of knowledge, confidence, and ability regarding key concepts. Complete data were available for 22 participants across 5 workshops. The mean scores on the general item scale changed from 6.0 to 8.7 and the scores on the sexuality and intimacy scale changed from 6.5 to 8.8. The single question with the lowest mean score was “I am knowledgeable about techniques to increase sexual comfort after breast cancer,” with a mean score at pre-test of 3.9 and with improvement to a mean of 8.8 at post-test. Interestingly, women attending the workshops indicated high levels of confidence in making “one change in my life to promote better emotional/physical health” on the pre-test with a mean score of 8.3 that improved to 9.3 at post-test. When we separately examined results from each of the three clinical sites where the workshops were held, we saw similar patterns for the scales and individual items.

We also sought to obtain more general feedback on the workshop experience from the participants. Table 2 highlights some of the themes reported as feedback provided on the evaluation surveys. Overall, participants indicated that the program was helpful and provided valuable information for navigating life after breast cancer. A positive aspect commonly reported was the connection to other young survivors with similar issues, which was a priority identified in the needs assessment. Participants shared an appreciation for the exercises and many requested more time to complete the exercises thoroughly. Additionally, participants felt the information was unique and relevant to them and appreciated the expertise of the facilitators. Several participants suggested that face-to-face programming should be supported by providing YBCS a list of relevant resources.

There was mixed feedback with regard to having a one-day seminar format or a two-session format; however, most of the participants wanted the sessions to be longer to allow for more sharing and discussion. In general, the feedback was very positive indicating that the program content was highly valued and well received. With the two session format there was a risk for participant attrition at the second session; however, the two community sites preferred the two session format and did not find a problem with attendance at the second session. Conducting the program in one day retained all participants for all intervention content, and allowed for better transition into the topics in the second half, which focused on more sensitive topics. Given the modular content of the program, future use should be determined by the clinical setting and patient population.

3.4 Training & Dissemination

Part of the original grant proposal as well as part of the goal of the YBCS program was to provide services outside of academic settings for use at additional facilities serving YBCS. Therefore, the UCLA team partnered with two community hospitals in the Los Angeles area, to train local facilitators to deliver the intervention at their respective hospitals.

Accordingly, staff members from each partnering hospital were part of all the developmental phases of the program and had participated in facilitator training, which included (a) observing UCLA facilitators delivering one entire session, (b) engaging in post-session debriefing (c) receiving the intervention manual and other program materials, and (d) participating in follow-up phone conferences. Facilitator training occurred during the 3rd and 4th program sessions. In addition to learning program content, partnering staff also provided feedback to facilitators and organizers, which was used to refine the intervention. The fifth workshop at UCLA was video and audio taped, with permission of the group participants, for a training video for prospective facilitators who would like to implement this program to their own organizations. The training video and manual are available through request at the Simms/Mann-UCLA Center for Integrative Oncology (http://www.simmsmanncenter.ucla.edu/), and will be available for more widespread dissemination to serve this community of YBCS.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Strengths and limitations of the LABC intervention program

Few psychosocial programs exist that are tailored to the specific needs of younger women with breast cancer. The LABC intervention is based on principles of mindfulness-based cognitive-behavioral therapy, biobehavioral stress management, narrative therapy and sex and couples therapy. The intervention was specifically tailored to meet the unique needs of young BCS that are not being addressed by existing programming. The program was structured around a new cognitive behavioral tool for stress management created by the first author (See Figure 1) specifically for this program.

The LABC intervention program was designed to address psychosocial needs of YBCS soon after completion of treatment, as a matter of routine care. Prior research on psychosocial programs for cancer patients and survivors have shown that these programs are largely efficacious in reducing distress and improving quality of life.[14]. In particular, research highlights the benefits of mindfulness based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral strategies for improvement in mood, fatigue and sleep disturbances in women treated for breast cancer [18,19]. In addition, several decades of literature on positive coping stresses the value of acceptance, positive reappraisal, and emotional expressiveness in facilitating improved coping with health stressors [20–23]. Based on the weight of this previous research, we developed a related program that fits the specific needs of this target population that could be tested for effectiveness in real-world settings and disseminated without lengthy phases of efficacy testing [24]. To this end, we incorporated evidence-based psychological principles, including elements from mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy, Acceptance and Change Therapy [15] and sex and relationship counseling interventions [16,17] into an interactive group format with both psychoeducation and group counseling components. The intervention also introduced a new model (Figure 1) for psychoeducation of cognitive behavioral strategies that allows participants room for acceptance of uncertainty while assisting them to reinforce strength/values based choices and create behavioral coping strategies as the basis of healthy survivorship.

In spite of the encouraging results from the pilot testing of this intervention program, it was developed and primarily delivered by two experienced health psychologists, who then trained social workers and a nurse to deliver the program at their institutions. Much more work needs to be done to establish the feasibility of implementation in diverse settings without the hands on training that was received by the secondary facilitators. In addition, the acceptability of this program to YBCS could reflect regional characteristics of these women, and not be universally applicable. Finally, because the original intent of the project was program development and not formal evaluation of the program, the measures used to assess participant feedback were limited and more qualitative, with the goal of refining the program as necessary through this feedback. For that reason detailed medical and demographic data were not requested from the participants.

4.2 Practice Implications

Pilot testing and subsequent intervention workshop groups conducted at community facilities indicated that the LABC program was well-received and acceptable to YBCS as well as to facilitators from both academic and community settings. Positive feedback confirmed this program is unique and highly regarded as something that addresses common unmet needs. Further, qualitative feedback suggested that participants enjoyed and valued the program, and learned concrete skills for managing anxiety about cancer recurrence and for rebuilding intimacy after cancer. We have preliminary evidence that this program can be delivered by existing staff associated with a community oncology center (nurse or social worker), which is one possible model of integrating this psychosocial intervention with oncology care for young BCS. Further, the fact that the program can be delivered in one session or divided into two sessions allows flexibility for delivery in multiple types of clinical settings and tailored to the needs of the institution and patient preferences. The LABC intervention is unique in that it connects YBCS with one another in a controlled professional environment, allowing them the opportunity to share their experiences and concerns with each other, while also facilitating learning and practice of skills they can utilize in their day-to-day lives to better their health and wellbeing.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

CDC funding led to creation of psychosocial intervention for YBCS.

Community needs assessment revealed gaps in services and needs of young survivors.

Psychosocial intervention developed and pilot tested.

5 workshops delivered - results showing gain in confidence, ability, and knowledge.

LABC is unique, connecting young survivors and teaching skills for survivorship.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Cooperative Agreement Number 1U58DP003429 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and by the UCLA Cancer Education and Career Development Program, NCI Grant R25 CA 87949. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This program was also supported by the Simms/Mann – UCLA Center for Integrative Oncology, David Geffen School of Medicine.

Appendix Pre/Post Test

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2013. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):52–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Facts & Figures 2012–2013. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/

- 5.Gabriel CA, Domcheck SM. Breast cancer in young women. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:212–21. doi: 10.1186/bcr2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howard-Anderson J, Ganz PA, Bower JE, Stanton AL. Quality of life, fertility concerns, and behavioral health outcomes in younger breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koch L, Bertram H, Eberle A, Holleczek B, Schmid-Höpfner S, et al. Fear of recurrence in long-term breast cancer survivors-still an issue. Results on prevalence, determinants, and the association with quality of life and depression from the cancer survivorship--a multi-regional population-based study. Psycho-oncology. 2014;23(5):547–54. doi: 10.1002/pon.3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koch L, Jansen L, Brenner H, Arndt V. Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long-term (≥5 years) cancer survivors--a systematic review of quantitative studies. Psycho-oncology. 2013;22(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/pon.3022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanton A. Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 24:5132–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, et al. Breast cancer in younger women: Reproductive and late health effects of treatment. J Clin Onc. 2003;21:4184–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, et al. Life after breast cancer: Understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Onc. 1998;16:501–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, et al. A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2009;18:276–83. doi: 10.1002/pon.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalaitzi C, Papadopoulos VP, Michas K, Vlasis K, Skandalakis P, Filippou D. Combined brief psychosexual intervention after mastectomy: Effects on sexuality, body image, and psychological well-being. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:235–240. doi: 10.1002/jso.20811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanton AL. What Happens Now? Psychosocial Care for Cancer Survivors After Medical Treatment Completion. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(11):1215–1220. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krychman ML, Katz A. Breast cancer and sexuality: Multi-modal treatment options. J Sex Med. 2012;9:5–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basson R. Women’s sexual dysfunction: Revised and expanded definitions. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;172:1327–33. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1020174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garland SN, Carslon LE, Stephens AJ, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction compared with cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of insomnia comorbid with cancer: A randomized, partially blinded, noninferiority trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:449–457. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Branstrom R, Kvillemo P, Moskowitz JT. A randomized study of the effects of mindfulness training on psychological well-being and symptoms of stress in patients treated for cancer at 6 month follow-up. Int J Behav Med. 2012;19:535–542. doi: 10.1007/s12529-011-9192-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilton AB. The relationship of uncertainty, control, commitment and threat of recurrence to coping strategies used by women diagnosed with breast cancer. J Behav Med. 1989;12:39–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00844748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Cameron CL, et al. Emotionally expressive coping predits psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer. J Consul and Clin Psy. 2000;68:875–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor SE, Stanton AL. Coping resources, coping processes and mental health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:377–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchand E, Stice E, Rohde P, Becker C. Moving from efficacy to effectiveness trials in prevention research. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2011;49:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.