Abstract

Peroxisomes are dynamic, vital organelles that sequester a variety of oxidative reactions and their toxic byproducts from the remainder of the cell. The oxidative nature of peroxisomal metabolism predisposes the organelle to self-inflicted damage, highlighting the need for a mechanism to dispose of damaged peroxisomes. In addition, the metabolic requirements of plant peroxisomes change during development, and obsolete peroxisomal proteins are degraded. Although pexophagy, the selective autophagy of peroxisomes, is an obvious mechanism for executing such degradation, pexophagy has only recently been described in plants. Several recent studies in the reference plant Arabidopsis thaliana implicate pexophagy in the turnover of peroxisomal proteins, both for quality control and during functional transitions of peroxisomal content. In this review, we describe our current understanding of the occurrence, roles, and mechanisms of pexophagy in plants.

Keywords: autophagy, LON protease, organelle quality control, peroxisome, pexophagy, protein degradation

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Plant peroxisomes are essential for embryonic and seedling development. Plant peroxisomes house various oxidative reactions including the glyoxylate cycle, several steps in photorespiration, and β-oxidation of fatty acids and hormone precursors [reviewed in 1]. Many peroxisomal enzymes produce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) as a byproduct, and peroxisomes also house catalase and other enzymes that eliminate H2O2. Unlike in mammals, where β-oxidation occurs in mitochondria as well as peroxisomes, peroxisomes are the sole site of β-oxidation in plants and fungi [reviewed in 2]. Plants with defective peroxisomes – and therefore impaired fatty acid β-oxidation – often require an exogenous fixed carbon source (e.g., sucrose) during seedling development when seed stores of triacylglycerol are normally catabolized. Plant peroxisomes also use β-oxidation to convert the auxin precursor indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) to the active auxin indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) [reviewed in 3]. Mutant plants with defective peroxisomes are often resistant to IBA because they inefficiently convert IBA into IAA [reviewed in 4].

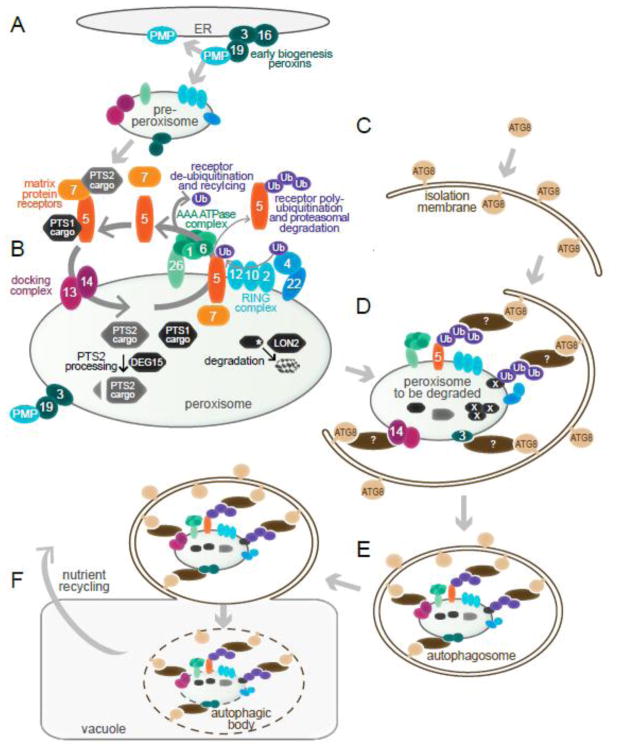

Peroxin (PEX) proteins facilitate peroxisome biogenesis or protein import [Fig. 1; reviewed in 1, 5]. Peroxisomal membrane proteins (PMPs) can be recognized by PEX19, a receptor that docks with PEX3 in the membrane to allow PMP insertion (Fig. 1A). Proteins delivered to the peroxisome matrix usually have one of two peroxisomal targeting signals: PTS1 or PTS2 (Fig. 1B). The PTS1 is a C-terminal, 3-amino-acid sequence recognized by PEX5; the PTS2 is a 9-amino-acid sequence near the N-terminus recognized by PEX7. In mammals and plants, PEX5 and PEX7 along with their respective cargos form a complex that docks with the PEX13 and PEX14 PMPs, allowing import of fully-folded proteins into the peroxisome matrix [reviewed in 1]. Once a PTS2 protein enters the peroxisome, the PTS2 region is removed to yield a mature form in plants [6, 7] and mammals [8]. The resulting difference in molecular mass between precursor PTS2 proteins and mature proteins can be visualized by immunoblotting, providing a useful assay for characterizing plant peroxisomal mutants [reviewed in 4], which often accumulate the precursor protein.

Fig. 1. Working model for Arabidopsis peroxisome biogenesis and destruction via pexophagy.

A) Peroxisomes can be generated de novo from the ER. PEX3, PEX16, and PEX19 facilitate insertion of peroxisomal membrane proteins (PMPs) into membranes, which is necessary for budding of pre-peroxisomes from the ER.

B) Peroxisome matrix proteins are imported using a suite of peroxins (numbered ovals). Proteins bearing either a C-terminal peroxisomal-targeting sequence 1 (PTS1) or an N-terminal PTS2 bind to PEX5 or PEX7, respectively. The resulting complex docks with PEX13 and PEX14, allowing cargo import. Following import, membrane-associated PEX5 is ubiquitinated via the PEX4 ubiquitin (Ub)-conjugating enzyme and the complex of Ub-protein ligases (PEX2, PEX10, and PEX12). Ubiquitinated PEX5 is removed from the peroxisomal membrane by a heterohexameric AAA-ATPase complex of PEX1 and PEX6, and de-ubiquitinated PEX5 can facilitate further rounds of import. Alternatively, polyubiquitinated PEX5 undergoes proteasomal degradation. Inside the peroxisome, the protease DEG15 removes the N-terminal PTS2 region of PTS2 proteins, and the protease LON2 is positioned to degrade obsolete or damaged matrix proteins (marked with a white asterisk).

C) During early stages of autophagy, a double membrane referred to as an isolation membrane forms. The ubiquitin-like protein ATG8 is conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine, allowing its localization to the isolation membrane.

D) During pexophagy, condemned peroxisomes are selectively recruited to expanding isolation membranes. A selective autophagy receptor (brown ovals) is postulated to bind to the peroxisome and to ATG8, connecting the condemned organelle to the autophagy machinery. The signal on plant peroxisomes that is recognized by the selective autophagy receptor to mark the peroxisome for degradation has not been identified, but candidates include ubiquitinated proteins, such as PEX5 or a matrix protein; PMPs, such as PEX3 and PEX14; and oxidized or aggregated matrix proteins (marked with white X).

E) The isolation membrane completely encloses its cargo, forming an autophagosome.

F) The autophagosome merges with the vacuole, forming an autophagic body, and the contents of the autophagic body are degraded into their constitutive nutrients (e.g., amino acids and lipids) and released into the cytosol for reuse.

After cargo delivery, PEX5 in the peroxisomal membrane can be ubiquitinated through the action of peroxisomal ubiquitin-protein ligases (PEX2, PEX10, and PEX12) and PEX4, a peroxisome-tethered ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (Fig. 1B). Ubiquitinated PEX5 is exported by a heterohexamer of PEX1 and PEX6 and can be degraded or de-ubiquitinated for use in further rounds of import [reviewed in 9]. The peroxins involved in PEX5 recycling are similar to the enzymes acting in endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated protein degradation [10, 11], and matrix proteins are stabilized in mutants defective in these peroxins [12–15]. These finding have prompted speculation that the PEX5-recycling peroxins might also act in targeting peroxisomal matrix proteins for degradation during developmental organelle remodeling.

Autophagy is a conserved bulk degradation process whereby proteins and even entire organelles are broken down to recycle their constituent materials [reviewed in 16]. Macroautophagy, hereafter referred to as autophagy, utilizes a double membrane known as an isolation membrane (Fig. 1C) to surround substrates to be degraded, forming an autophagosome (Fig. 1D, E). The autophagosome fuses with the lysosome (in animals) or vacuole (in plants and yeast) (Fig. 1F). Once in the vacuole, the complex, now referred to as an autophagic body, is lysed, the substrates are degraded, and the nutrients are exported to the cytosol for reuse (Fig. 1F). Over 30 autophagy-related (ATG) proteins have been identified, and a core set of these proteins are conserved in plants [reviewed in 16]. The ubiquitin-like protein ATG8 (known as microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 [LC3] in mammals) decorates the isolation membrane and autophagosome (Fig. 1C–E) and is generally used as a docking site for receptors that target substrates to the isolation membrane (Fig. 1D).

Autophagy functions in stress responses, nutrient recycling, and protein quality control in plants. Because autophagy is not required for viability in Arabidopsis thaliana [17], null alleles lacking core autophagy components can be used to query the range of processes impacted by autophagy during plant growth and development. Arabidopsis atg mutants are hypersensitive to biotic stressors such as fungal infection [18] and abiotic stressors, including heat stress [19], drought stress [20], salt stress [20], and oxidative stress [21]. Arabidopsis atg mutants also exhibit premature senescence, which is attributed to salicylic acid accumulation [22]. Furthermore, autophagy is induced in Arabidopsis plants during nutrient starvation [23], and atg mutants are typically hypersensitive to carbon or nitrogen starvation [17], supporting a role for autophagy in nutrient recycling. Autophagy also serves a quality control function in Arabidopsis. For instance, autophagy clears inactivated proteasomes [24] and is induced following treatment with tunicamycin, which induces ER stress via the unfolded protein response [25]. In addition to nonselective autophagy, which appears to promote survival under stress conditions, there is growing evidence for selective autophagy whereby specific proteins, protein complexes, infectious agents, or organelles are targeted for autophagy [reviewed in 16].

Pexophagy is specialized autophagy that degrades excess and damaged peroxisomes. Pexophagy is well-documented in yeast and mammals [reviewed in 26] and has long been postulated to exist in plants as well. A single EM image of a peroxisome surrounded by a double membrane in a castor bean endosperm [27] hinted at the possible occurrence of pexophagy in plants, but definitive evidence of pexophagy in plants only emerged very recently [28–31]. In this review, we discuss the physiological relevance of pexophagy and our current understanding of this fundamental pathway in plants.

2. Pexophagy is involved in peroxisome remodeling in seedlings

The functional requirements of peroxisomes change as seedlings mature. Germinating oilseed plants, such as Arabidopsis, initially depend on fatty acid β-oxidation and the glyoxylate cycle to convert stored lipids into carbohydrates [reviewed in 2]. Early seedling peroxisomes, formerly called glyoxysomes [32], contain two glyoxylate cycle enzymes, isocitrate lyase (ICL) and malate synthase (MLS), in addition to enzymes involved in β-oxidation [reviewed in 1]. The glyoxylate cycle allows the acetyl-CoA generated by fatty acid β-oxidation to be used to synthesize sugars. As seedlings mature and establish photosynthesis, the glyoxylate cycle becomes obsolete, and ICL and MLS are degraded [12, 13]. This developmental progression from seedling peroxisomes harboring glyoxylate cycle enzymes to leaf-type peroxisomes harboring photorespiration enzymes provides model substrates with which to study peroxisome and peroxisome matrix protein degradation. Three basic models of peroxisome remodeling during early seedling development have been put forward: the two-population model, the one-population model, and the continuous turnover model [reviewed in 33].

In the two-population model, peroxisomes harboring glyoxylate cycle enzymes are degraded in the vacuole via autophagy, and peroxisomes housing photorespiration enzymes are synthesized de novo from the ER. However, autophagy mutants barely stabilize ICL and MLS [28, 29], failing to support a basic prediction of the two-population model.

In the one-population model, glyoxylate cycle enzymes exist together with photorespiration enzymes in the same peroxisomes, and a protease degrades ICL and MLS as seedlings transition to photosynthesis. Immunolabeling experiments using greening cucurbit cotyledons reveal both glyoxylate cycle and photorespiration enzymes in the same peroxisomes [34–36], supporting the one-population model. Moreover, in vitro-synthesized MLS is stable when imported into peroxisomes purified from dark-grown seedlings or mature leaves but unstable when imported into transitional peroxisomes [37], suggesting that a peroxisomal protease is activated during the remodeling period. Reverse-genetic analyses of several Arabidopsis peroxisomal proteases failed to implicate a protease in this process [38]; however, additional peroxisomal proteases [reviewed in 39] remain to be tested. Rather than degradation by resident peroxisomal proteases, proteins might be retrotranslocated out of the peroxisome, polyubiquitinated, and degraded by the proteasome [12–15]. However, this idea has proven difficult to definitively test because mutants defective in the PEX5-recycling peroxins implicated in ubiquitination and retrotranslocation (Fig. 1B) also have defects in matrix protein import [14, 15], and efficient peroxisomal import is a prerequisite for efficient degradation of tested matrix proteins [13, 14].

In the continuous turnover model, peroxisomes are continuously formed de novo from the ER and degraded via autophagy. This model is based on the observation that peroxisomes associate with lipid bodies during germination, with lipid bodies and plastids during the transition period, and with plastids following depletion of lipid bodies [40]. This model received relatively little historical attention compared to the one- and two-population models but fits well with current findings.

Recent research has begun to solve the mystery of peroxisome remodeling by uncovering roles for both pexophagy and a peroxisomal protease in the process. LON2 is a peroxisomal protease that is positioned to degrade glyoxylate cycle enzymes. However, lon2 mutants fail to stabilize ICL or MLS [14, 38]. A suppressor screen revealed that disabling autophagy genes in lon2 mutants results in dramatic stabilization of ICL and MLS, indicating that autophagy is involved in degrading peroxisomal proteins when LON2 is nonfunctional [28]. This finding provided an early indication of the existence of pexophagy in plants [28, 41] and supports the idea that a basal level of pexophagy continuously turns over peroxisomes in plant cells.

3. Pexophagy is involved in quality control of plant peroxisomes

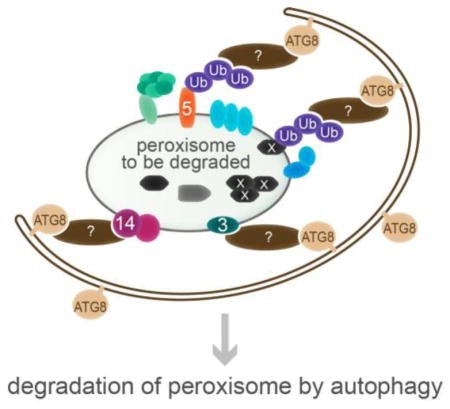

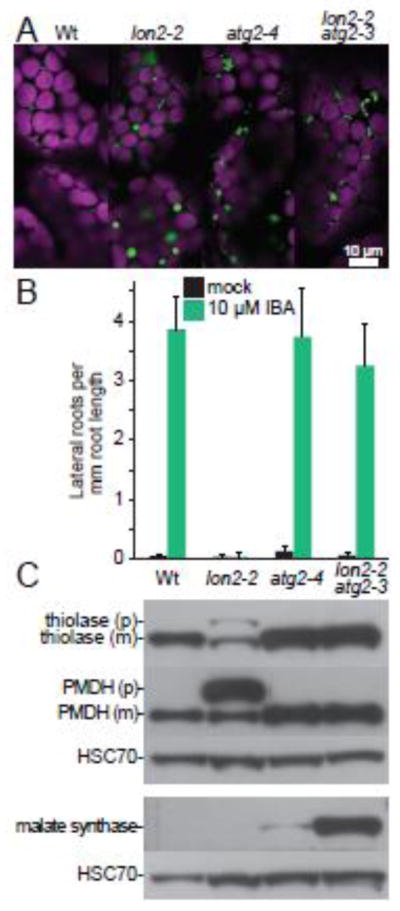

In addition to developmental remodeling, pexophagy is important for peroxisome quality control in plants. H2O2 is produced as a byproduct of β-oxidation, photorespiration, and other oxidative reactions housed in peroxisomes; this H2O2 subjects peroxisomal matrix proteins to oxidative damage [42–45]. Catalase detoxifies H2O2 by converting it to water and molecular oxygen [46], but catalase is itself susceptible to damage from H2O2 [47]. Autophagy-deficient seedlings accumulate peroxisomal aggregates of inactive catalase [30, 31], implying that pexophagy actively clears damaged peroxisomes. Furthermore, atg2 mutants exhibit clustered peroxisomes [Fig. 2A; 30], consistent with the possibility that the clustered peroxisomes are marked for degradation and gathered around the incompletely developed autophagy machinery that remains when ATG2 is absent.

Fig. 2. The peroxisomal protease LON2 inhibits pexophagy in Arabidopsis.

A) Preventing autophagy suppresses protein import defects and the large puncta phenotype of lon2-2. Cotyledon mesophyll cells in 8-d-old seedlings of the indicated genotypes expressing 35S:PTS2-GFP [81] were imaged for fluorescence using confocal microscopy. PTS2-GFP bears an N-terminal PTS2 that localizes GFP (green) to peroxisomes in wild-type Columbia-0 (Wt), atg2-4 and lon2-2 atg2-3. PTS2-GFP is partially cytosolic (diffuse fluorescence) in lon2-2. Peroxisomes are enlarged in lon2-2 and clustered in atg2-4 and lon2-2 atg2-3. Chlorophyll autofluorescence (magenta) marks chloroplasts. Scale bar = 10 μm.

B) Preventing autophagy suppresses the IBA resistance of lon2-2. Wild-type Columbia-0 (Wt), lon2-2 [38], atg2-4 [28], and lon2-2 atg2-3 [28] seeds were plated on medium containing 0.5% sucrose (mock) and grown for 4 days. Half of the seedlings were then transferred to medium supplemented with 0.5% sucrose and 10 μM IBA, and seedlings were grown for an additional 4 days before measuring lateral root formation. Error bars represent standard deviation of the means (n ≥ 10).

C) Preventing autophagy suppresses the PTS2-processing defect of lon2-2, and obsolete matrix proteins are stabilized in lon2-2 atg2-3 double mutants. Extracts from 6-day-old light-grown seedlings of the indicated genotypes were processed for immunoblotting in duplicate, and membranes were serially probed with antibodies recognizing the peroxisome matrix proteins thiolase [13] or malate dehydrogenase [PMDH; 82], shown in the upper panel, or malate synthase [MLS; 83], shown in the lower panel. Thiolase and PMDH are PTS2 proteins synthesized as precursors (p) in the cytosol and cleaved to mature forms (m) lacking the PTS2 region in the peroxisome. Protein loading was monitored by probing with an antibody recognizing HSC70 (SPA-817; StressGen Bioreagents).

Consistent with the notion that pexophagy mediates constant turnover of peroxisomes, pexophagy limits plant peroxisome abundance even in non-stress conditions. For example, Arabidopsis atg mutants have more peroxisomes than wild type [Fig. 2A; 29, 30], and a maize atg mutant displays increased levels of the PEX14 PMP [48]. Moreover, both carbon-starved and rapidly dividing tobacco cells display increased peroxisome abundance when treated with an autophagy inhibitor [49]. These findings are all consistent with the possibility that pexophagy clears damaged peroxisomes at a basal rate in the absence of stresses typically associated with inducing autophagy.

Pexophagy appears to occur at a higher basal rate than other types of selective autophagy, evidenced by the increased turnover of peroxisomal proteins relative to other organellar proteins. For example, leaves of atg5 mutants display increased levels of peroxisomal proteins but wild-type levels of selected Golgi, ER, mitochondrial, and chloroplast proteins [31], hinting that pexophagy may be more prevalent than autophagy of other organelles in seedling aerial tissue. Similarly, inhibiting autophagy in rapidly dividing tobacco cells heightens accumulation of peroxisomal marker proteins compared to plastidic or mitochondrial marker proteins [49].

Basal pexophagy rates appear to differ among various plant tissues. Arabidopsis atg mutants display increased peroxisome abundance and heightened peroxisomal protein levels in hypocotyls and leaves but not roots [29, 31]. A screen for mutants that stabilize GFP-ICL driven by the endogenous ICL promoter [14] recovered several atg7 and atg2 alleles, but these mutants show only weak and inconsistent stabilization of GFP-ICL in immunoblotting analysis of whole seedlings [50]. The primary screen was performed by microscopic examination of hypocotyls of EMS-mutagenized M2 seedlings [14], suggesting that GFP-ICL stabilization might occur preferentially in hypocotyls. Indeed, ICL and MLS stabilization in atg5 and atg7 mutants is more apparent in extracts prepared from hypocotyls than in extracts prepared from entire seedlings [29].

Perhaps increased oxidative damage is responsible for the prevalence of pexophagy in aerial tissue. The peroxisomal enzyme glycolate oxidase, which converts glycolate into glyoxylate during photorespiration, generates H2O2 as a byproduct [45], and photorespiration occurs in aerial tissue but not in roots. Intriguingly, elevated CO2 suppresses the enlarged peroxisome phenotype displayed in lon2 mutants [51]. This suppression is presumably due to decreased photorespiration (and in turn reduced H2O2 production), consistent with a role for photorespiration in promoting oxidative damage of peroxisomes. It will be interesting to learn whether this CO2-mediated suppression is light-dependent, which would be expected if photorespiration is required for the large-peroxisome phenotype observed in lon2 leaves. Together, available data suggest that increased oxidative damage necessitates more peroxisome turnover via pexophagy, particularly in aerial tissues.

4. The LON2 peroxisomal protease inhibits pexophagy

LON proteins are a conserved family of homo-oligomeric ATPases with both chaperone and protease activities that are involved in protein quality control [52, 53]. LON monomers are typically composed of an AAA (ATPase Associated with diverse cellular Activities) domain, which contains canonical Walker A and Walker B motifs as well as an arginine finger, and a protease domain, which contains a Ser-Lys catalytic dyad [52, 54]. LON proteases are thought to act as chaperones that attempt to recover misfolded proteins and as proteases for misfolded proteins that cannot be recovered [55, 56]. Eukaryotic LON isoforms are localized to organelles. In Arabidopsis, LON isoforms are targeted to mitochondria, chloroplasts, and peroxisomes [39]. LON1 [57] and LON4 [58] are dually localized to mitochondria and chloroplasts, and LON3 appears to be a pseudogene [58]. LON2 contains a canonical PTS1 and is localized to peroxisomes [58, 59].

LON2 plays an important but ill-defined role in preventing pexophagy. As a peroxisomal protease, LON2 is positioned to degrade obsolete glyoxylate cycle proteins. However, lon2 mutants fail to stabilize ICL or MLS [14, 28, 38]. A critical role for LON2 in peroxisome physiology is indicated by the peroxisome-defective phenotypes exhibited by lon2 mutants (Fig. 2): IBA resistance (inefficient β-oxidation of IBA into IAA), PTS2-processing defects, reduced matrix protein import, and enlarged peroxisomes [28, 38, 51]. Interestingly, these defects worsen as cells mature [38], consistent with the possibility that lon2 peroxisomes are functional in recently divided cells (e.g., in young cotyledons and root tips) but are degraded at an increased rate compared to wild type as cells mature. A lon2 suppressor screen revealed that preventing autophagy restores all four of the peroxisome-related phenotypes observed in lon2 mutants [Fig. 2; 28]. Furthermore, lon2 atg double mutants stabilize obsolete glyoxylate cycle proteins [Fig. 2C; 28], prompting the hypothesis that pexophagy is induced when LON2 is nonfunctional.

Expressing variants of LON2 with an inactive AAA domain or an inactive protease domain reveals distinct roles for LON2 domains in peroxisome maintenance [51]. Expressing protease-deficient, AAA-active lon2 in a lon2 null mutant prevents the rampant pexophagy that typifies lon2 mutants [51], suggesting that the AAA domain of LON2 normally prevents excessive pexophagy, perhaps by acting as a chaperone. Indeed, expressing AAA-deficient, protease-active lon2 in a lon2 null mutant fails to prevent excess pexophagy [51]. Intriguingly, glyoxylate cycle enzymes are stabilized when the protease-deficient, AAA-active lon2 is expressed in a lon2 mutant [51], implicating the protease domain in matrix protein turnover. Moreover, peroxisomes in lon2 mutants expressing protease-deficient lon2 are clustered and more abundant than in wild type, resembling peroxisomes in an atg2 mutant [51], suggesting that impeding the protease domain of LON2 inhibits pexophagy. Thus it appears that the AAA domain of LON2 restrains pexophagy regardless of the activity of the protease domain, and the protease activity of LON2 promotes pexophagy but only when the AAA domain is present [51].

The molecules that target peroxisomes for pexophagy in lon2 mutants remain unidentified. Immuno-electron microscopy analysis of a lon2 mutant reveals enlarged, irregularly-shaped peroxisomes harboring electron-dense regions containing nonfunctional catalase [51], suggesting that aggregated catalase might trigger pexophagy in lon2 mutants. Similarly, peroxisomes in the fungus Penicillium chrysogenum lacking peroxisomal Lon accumulate nonfunctional catalase-peroxidase [55]. However, although the fate of peroxisomes in plants lacking both LON2 and catalase has not been reported, catalase is not necessary for the peroxisome clustering that is observed in atg2 mutants [30], suggesting that catalase aggregates might be a symptom of peroxisome dysfunction rather than a signal for pexophagy.

Intriguingly, a mitochondrial Lon isoform regulates mitophagy (selective autophagy of mitochondria) in Drosophila [60]. The serine/threonine kinase PINK1 (PTEN-induced putative kinase 1) and the ubiquitin-protein ligase Parkin are central to mitophagy. Depolarized mitochondria accumulate PINK1 on the outer membrane, where it phosphorylates Ser65 of ubiquitin, which activates Parkin to ubiquitinate outer mitochondrial membrane proteins [61–65]. This ubiquitination provides additional PINK1 substrates, forming a positive feedback loop, and also marks the damaged mitochondria for degradation via mitophagy [66]. In Drosophila, healthy mitochondria avoid mitophagy by constitutively degrading PINK1, and several proteases have been implicated in this degradation, including mitochondrial Lon [60]. When mitochondrial membrane potential is disrupted, these proteases are rendered nonfunctional, allowing PINK1 to accumulate and trigger mitophagy [60, 67]. Although the Arabidopsis mitochondrial isoforms LON1 and LON4 have not been directly implicated in mitophagy, lon1 mutants display enlarged mitochondria [68], reminiscent of the large peroxisomes in lon2 mutants [Fig. 2A; 28, 38, 51]. It is tempting to speculate that Arabidopsis LON2 plays a role in plant peroxisomes analogous to the role that Drosophila Lon plays in mitochondria by degrading or disaggregating pexophagy-promoting factors in peroxisomes.

5. Plant pexophagy receptors remain to be identified

Selective autophagy utilizes receptors to target substrates for degradation (Fig. 1D). In yeast, Atg30 and Atg36 are pexophagy receptors [69, 70], but homologs of these proteins are not found in plants. In mammals, Neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 (NBR1) is involved in selective autophagy [71]. NBR1 contains an LC3-Interacting Region (LIR) and a Ubiquitin-Associated (UBA) domain. The LIR binds to ATG8/LC3, and the UBA domain binds to the ubiquitin on a ubiquitinated substrate [72]. In mammals, NBR1 is necessary and sufficient for pexophagy and acts synergistically with p62, a similar selective autophagy receptor [73].

As the only characterized pexophagy receptor from other organisms with a plant homolog [74, 75], NBR1 is an attractive plant pexophagy receptor candidate. Consistent with a role for NBR1 as a selective autophagy receptor, Arabidopsis nbr1 mutants exhibit only a subset of atg mutant phenotypes. For example, both nbr1 and atg mutants are susceptible to heat, drought, salt, and oxidative stresses and accumulate ubiquitinated substrates during heat stress [19]. However, atg mutants exhibit heightened age- and dark-induced senescence and fungal susceptibility, but nbr1 mutants do not [19]. Peroxisomes are likely essential for fatty acid β-oxidation during age- and dark-induced senescence [76], and some of the oxidative reactions in peroxisomes, including jasmonate biosynthesis, are critical for resistance to fungal infection [77], suggesting that peroxisomes may need to avoid pexophagy during certain stresses that increase general autophagy. Intriguingly, quantitative proteomic analysis identified several peroxisomal matrix proteins among the proteins that over-accumulate in nbr1 mutants during heat stress [78], consistent with the possibility that NBR1 promotes pexophagy during heat stress. However, no direct evidence has connected NBR1 to pexophagy in plants. Considering the variety of pexophagy receptors in different organisms, it would not be surprising if plants have novel pexophagy receptors.

6. How do plant peroxisomes signal for their destruction?

The signals that mark peroxisomes for pexophagy are not identified in plants. Although nonfunctional catalase accumulates in atg2 mutants, atg2 cat2 cat3 triple mutants, which lack detectable catalase, still exhibit the clustered peroxisome phenotype associated with atg2 mutants [30]. This result indicates that aggregated catalase is not a necessary signal for pexophagy. The observation that expressing lon2 with a functional AAA domain and a nonfunctional protease domain prevents the excessive pexophagy of lon2 mutants [51] suggests that the chaperone function of LON2 suppresses pexophagy. This suppression supports a hypothesis that misfolded or aggregated matrix protein(s) may signal for pexophagy (Fig. 1D). Such a signal would presumably need to traverse the peroxisome membrane to be recognized by a cytosolic pexophagy receptor. Moreover, the pexophagy receptor may require the PEX4 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme and the PEX2/PEX10/PEX12 ubiquitin-protein ligases to ubiquitinate the misfolded or aggregated protein prior to recognition.

Other candidates for pexophagy receptor targets include peroxins (Fig. 1D). PEX5 is ubiquitinated in yeast and mammals as it is recycled back into the cytosol for further import rounds [9], making ubiquitinated PEX5 an attractive candidate pexophagy signal. Indeed, preventing efficient retrotranslocation of PEX5 by addition of a bulky C-terminal tag can trigger peroxisome degradation via autophagy in a mammalian cell line [79]. In addition, knockdown of the docking protein PEX14 reduces pexophagy in mammals [73], which might indicate that mammalian PEX14 is directly required to bind a pexophagy receptor or that PEX14 is indirectly required because it is needed to import the actual pexophagy signal, be it ubiquitinated PEX5, a PEX5-dependent matrix protein, or a PEX5-dependent process (e.g., oxidative damage). A direct role for PEX14 in pexophagy is suggested in Pichia, where the pexophagy receptor Atg30 interacts with phosphorylated Pex14 [69]. Moreover, the Pichia Atg30 receptor also interacts with Pex3 [69, 80], as does the Saccharomyces pexophagy receptor Atg36 [70]. However, homologs of Atg30 and Atg36 are not found in plants, and no connection between specific peroxins and pexophagy has been established in plants.

7. Conclusions and future prospects

The core autophagy machinery is conserved across kingdoms. Plants, fungi, and metazoans all utilize autophagy to maintain intracellular quality, recycle nutrients, and respond to stress. The oxidative nature of peroxisomes is also conserved and necessitates a mechanism to turn over these vital organelles, and pexophagy performs this function not only in fungi and animals but also in plants.

Considering the conservation of autophagic pathways, the similarities between pexophagy in plants and other organisms likely outweigh the differences. Although pexophagy receptors are often unique to particular organisms, all examined systems are unified in utilizing a receptor protein to link condemned peroxisomes to the autophagy machinery. It will be exciting to discover the molecular components executing pexophagy in plants as well as the triggers that promote pexophagy in response to environmental and developmental changes. Moreover, it will be interesting to apply the knowledge gained from the study of plant peroxisomes, such as the role of the LON2 peroxisomal protease in preventing pexophagy, to other organisms.

Highlights.

Selective autophagy helps maintain a healthy population of peroxisomes.

Pexophagy degrades peroxisomes when the LON2 peroxisomal protease is dysfunctional.

Both autophagy and LON2 aid in efficient degradation of peroxisomal proteins.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to those whose work could not be cited due to space constraints. We are grateful to Kim Gonzalez, Yun-Ting Kao, Jose Olmos, Jr., Michael Passalacqua, Andrew Woodward, and Zachary Wright for critical comments on the manuscript. The authors’ peroxisome research is funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM079177), the National Science Foundation (MCB-1516966), and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (C-1309). Confocal microscopy was performed on equipment obtained through a Shared Instrumentation Grant from the NIH (S10RR026399-01).

Abbreviations

- AAA

ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities

- ATG

autophagy related

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- IAA

indole-3-acetic acid

- IBA

indole-3-butyric acid

- ICL

isocitrate lyase

- LIR

LC3-interacting region

- MLS

malate synthase

- NBR1

Neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1

- PEX

peroxin

- PINK1

PTEN-induced putative kinase 1

- PMDH

peroxisomal malate dehydrogenase

- PMP

peroxisomal membrane protein

- PTS

peroxisomal targeting signals

- Ub

ubiquitin

- UBA

ubiquitin associated

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hu J, Baker A, Bartel B, Linka N, Mullen RT, Reumann S, Zolman BK. Plant peroxisomes: biogenesis and function. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2279–2303. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.096586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham IA. Seed storage oil mobilization. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:115–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strader LC, Bartel B. Transport and metabolism of the endogenous auxin precursor indole-3-butyric acid. Mol Plant. 2011;4:477–486. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartel B, Burkhart S, Fleming W. Protein transport in and out of plant peroxisomes. In: Brocard C, Hartig A, editors. Molecular Machines Involved in Peroxisome Biogenesis and Maintenance. Springer; Vienna: 2014. pp. 325–345. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cross LL, Ebeed HT, Baker A. Peroxisome biogenesis, protein targeting mechanisms and PEX gene functions in plants. BBA - Molecular Cell Research. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.09.027. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helm M, Luck C, Prestele J, Hierl G, Huesgen PF, Frohlich T, Arnold GJ, Adamska I, Gorg A, Lottspeich F, Gietl C. Dual specificities of the glyoxysomal/peroxisomal processing protease Deg15 in higher plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11501–11506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704733104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schuhmann H, Huesgen PF, Gietl C, Adamska I. The DEG15 serine protease cleaves peroxisomal targeting signal 2-containing proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1847–1856. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.125377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swinkels BW, Gould S, Bodnar A, Rachubinski R, Subramani S. A novel, cleavable peroxisomal targeting signal at the amino-terminus of the rat 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase. EMBO J. 1991;10:3255–3262. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Platta HW, Hagen S, Reidick C, Erdmann R. The peroxisomal receptor dislocation pathway: To the exportomer and beyond. Biochimie. 2014;98:16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolte K, Gruenheit N, Felsner G, Sommer MS, Maier UG, Hempel F. Making new out of old: Recycling and modification of an ancient protein translocation system during eukaryotic evolution. BioEssays. 2011;33:368–376. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schliebs W, Girzalsky W, Erdmann R. Peroxisomal protein import and ERAD: variations on a common theme. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:885–890. doi: 10.1038/nrm3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zolman BK, Monroe-Augustus M, Silva ID, Bartel B. Identification and functional characterization of Arabidopsis PEROXIN4 and the interacting protein PEROXIN22. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3422–3435. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lingard MJ, Monroe-Augustus M, Bartel B. Peroxisome-associated matrix protein degradation in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4561–4566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811329106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burkhart SE, Lingard MJ, Bartel B. Genetic dissection of peroxisome-associated matrix protein degradation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2013;193:125–141. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.146100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burkhart SE, Kao YT, Bartel B. Peroxisomal ubiquitin-protein ligases Peroxin2 and Peroxin10 have distinct but synergistic roles in matrix protein import and Peroxin5 retrotranslocation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2014;166:1329–1344. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.247148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li F, Vierstra RD. Autophagy: A multifaceted intracellular system for bulk and selective recycling. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:526–537. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doelling JH, Walker JM, Friedman EM, Thompson AR, Vierstra RD. The APG8/12-activating enzyme APG7 is required for proper nutrient recycling and senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33105–33114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai Z, Wang F, Zheng Z, Fan B, Chen Z. A critical role of autophagy in plant resistance to necrotrophic fungal pathogens. Plant J. 2011;66:953–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou J, Wang J, Cheng Y, Chi YJ, Fan B, Yu JQ, Chen Z. NBR1-mediated selective autophagy targets insoluble ubiquitinated protein aggregates in plant stress responses. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Xiong Y, Bassham DC. Autophagy is required for tolerance of drought and salt stress in plants. Autophagy. 2009;5:954–963. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.7.9290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong Y, Contento AL, Nguyen PQ, Bassham DC. Degradation of oxidized proteins by autophagy during oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:291–299. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.092106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshimoto K, Jikumaru Y, Kamiya Y, Kusano M, Consonni C, Panstruga R, Ohsumi Y, Shirasu K. Autophagy negatively regulates cell death by controlling NPR1-dependent salicylic acid signaling during senescence and the innate immune response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2914–2927. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suttangkakul A, Li F, Chung T, Vierstra RD. The ATG1/ATG13 protein kinase complex is both a regulator and a target of autophagic recycling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011;23:3761–3779. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.090993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall RS, Li F, Gemperline DC, Book AJ, Vierstra RD. Autophagic degradation of the 26S proteasome is mediated by the dual ATG8/ubiquitin receptor RPN10 in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell. 2015;58:1053–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Burgos JS, Deng Y, Srivastava R, Howell SH, Bassham DC. Degradation of the endoplasmic reticulum by autophagy during endoplasmic reticulum stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4635–4651. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.101535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Till A, Lakhani R, Burnett SF, Subramani S. Pexophagy: the selective degradation of peroxisomes. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:Article ID 512721. doi: 10.1155/2012/512721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vigil EL. Cytochemical and developmental changes in microbodies (glyoxysomes) and related organelles of castor bean endosperm. J Cell Biol. 1970;46:435–454. doi: 10.1083/jcb.46.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farmer LM, Rinaldi MA, Young PG, Danan CH, Burkhart SE, Bartel B. Disrupting autophagy restores peroxisome function to an Arabidopsis lon2 mutant and reveals a role for the LON2 protease in peroxisomal matrix protein degradation. Plant Cell. 2013;25:4085–4100. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.113407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim J, Lee H, Lee HN, Kim SH, Shin KD, Chung T. Autophagy-related proteins are required for degradation of peroxisomes in Arabidopsis hypocotyls during seedling growth. Plant Cell. 2013;25:4956–4966. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.117960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shibata M, Oikawa K, Yoshimoto K, Kondo M, Mano S, Yamada K, Hayashi M, Sakamoto W, Ohsumi Y, Nishimura M. Highly oxidized peroxisomes are selectively degraded via autophagy in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:4967–4983. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.116947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yoshimoto K, Shibata M, Kondo M, Oikawa K, Sato M, Toyooka K, Shirasu K, Nishimura M, Ohsumi Y. Organ-specific quality control of plant peroxisomes is mediated by autophagy. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:1161–1168. doi: 10.1242/jcs.139709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pracharoenwattana I, Smith SM. When is a peroxisome not a peroxisome? Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:522–525. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beevers H. Microbodies in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1979;30:159–193. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Titus DE, Becker WM. Investigation of the glyoxysome-peroxisome transition in germinating cucumber cotyledons using double-label immunoelectron microscopy. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:1288–1299. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishimura M, Yamaguchi J, Mori H, Akazawa T, Yokota S. Immunocytochemical analysis shows that glyoxysomes are directly transformed to leaf peroxisomes during greening of pumpkin cotyledons. Plant Physiol. 1986;81:313–316. doi: 10.1104/pp.81.1.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sautter C. Microbody transition in greening watermelon cotyledons. Double immunocytochemical labeling of isocitrate lyase and hydroxypyruvate reductase. Planta. 1986;167:491–503. doi: 10.1007/BF00391225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori H, Nishimura M. Glyoxysomal malate synthetase is specifically degraded in microbodies during greening of pumpkin cotyledons. FEBS Lett. 1989;244:163–166. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lingard MJ, Bartel B. Arabidopsis LON2 is necessary for peroxisomal function and sustained matrix protein import. Plant Physiol. 2009;151:1354–1365. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.142505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Wijk KJ. Protein maturation and proteolysis in plant plastids, mitochondria, and peroxisomes. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2015;66:75–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043014-115547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schopfer P, Bajracharya D, Bergfeld R, Falk H. Phytochrome-mediated transformation of glyoxysomes into peroxisomes in the cotyledons of mustard (Sinapis alba L.) seedlings. Planta. 1976;133:73–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00386008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bartel B, Farmer LM, Rinaldi MA, Young PG, Danan CH, Burkhart SE. Mutation of the Arabidopsis LON2 peroxisomal protease enhances pexophagy. Autophagy. 2014;10:518–519. doi: 10.4161/auto.27565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adham AR, Zolman BK, Millius A, Bartel B. Mutations in Arabidopsis acyl-CoA oxidase genes reveal distinct and overlapping roles in β-oxidation. Plant J. 2005;41:859–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van den Bosch H, Schutgens RB, Wanders RJ, Tager JM. Biochemistry of peroxisomes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:157–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.001105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eastmond PJ, Hooks M, Graham IA. The Arabidopsis acyl-CoA oxidase gene family. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28:755–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fahnenstich H, Scarpeci TE, Valle EM, Flugge UI, Maurino VG. Generation of hydrogen peroxide in chloroplasts of Arabidopsis overexpressing glycolate oxidase as an inducible system to study oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:719–729. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.126789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willekens H, Chamnongpol S, Davey M, Schraudner M, Langebartels C, Van Montagu M, Inze D, Van Camp W. Catalase is a sink for H2O2 and is indispensable for stress defence in C3 plants. EMBO J. 1997;16:4806–4816. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anand P, Kwak Y, Simha R, Donaldson RP. Hydrogen peroxide induced oxidation of peroxisomal malate synthase and catalase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;491:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li F, Chung T, Pennington JG, Federico ML, Kaeppler HF, Kaeppler SM, Otegui MS, Vierstra RD. Autophagic recycling plays a central role in maize nitrogen remobilization. Plant Cell. 2015;27:1389–1408. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Voitsekhovskaja OV, Schiermeyer A, Reumann S. Plant peroxisomes are degraded by starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in tobacco BY-2 suspension-cultured cells. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:629. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burkhart S. BioSciences. Rice University; 2013. Using forward genetics to elucidate peroxisome biogenesis and peroxisome-associated protein degradation in Arabidopsis thaliana. https://scholarship.rice.edu/handle/1911/76470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goto-Yamada S, Mano S, Nakamori C, Kondo M, Yamawaki R, Kato A, Nishimura M. Chaperone and protease functions of LON protease 2 modulate the peroxisomal transition and degradation with autophagy. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:482–496. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Venkatesh S, Lee J, Singh K, Lee I, Suzuki CK. Multitasking in the mitochondrion by the ATP-dependent Lon protease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iyer LM, Leipe DD, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Evolutionary history and higher order classification of AAA+ ATPases. J Struct Biol. 2004;146:11–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rigas S, Daras G, Tsitsekian D, Alatzas A, Hatzopoulos P. Evolution and significance of the Lon gene family in Arabidopsis organelle biogenesis and energy metabolism. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:145. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bartoszewska M, Williams C, Kikhney A, Opalinski L, van Roermund CW, de Boer R, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ. Peroxisomal proteostasis involves a Lon family protein that functions as protease and chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:27380–27395. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.381566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wohlever ML, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Roles of the N domain of the AAA+ Lon protease in substrate recognition, allosteric regulation and chaperone activity. Mol Microbiol. 2014;91:66–78. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daras G, Rigas S, Tsitsekian D, Zur H, Tuller T, Hatzopoulos P. Alternative transcription initiation and the AUG context configuration control dual-organellar targeting and functional competence of Arabidopsis Lon1 protease. Mol Plant. 2014;7:989–1005. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ostersetzer O, Kato Y, Adam Z, Sakamoto W. Multiple intracellular locations of Lon protease in Arabidopsis: Evidence for the localization of AtLon4 to chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:881–885. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reumann S, Quan S, Aung K, Yang P, Manandhar-Shrestha K, Holbrook D, Linka N, Switzenberg R, Wilkerson CG, Weber APM, Olsen LJ, Hu J. In-depth proteome analysis of Arabidopsis leaf peroxisomes combined with in vivo subcellular targeting verification indicates novel metabolic and regulatory functions of peroxisomes. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:125–143. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.137703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thomas RE, Andrews LA, Burman JL, Lin WY, Pallanck LJ. PINK1-Parkin pathway activity is regulated by degradation of PINK1 in the mitochondrial matrix. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koyano F, Okatsu K, Kosako H, Tamura Y, Go E, Kimura M, Kimura Y, Tsuchiya H, Yoshihara H, Hirokawa T, Endo T, Fon EA, Trempe JF, Saeki Y, Tanaka K, Matsuda N. Ubiquitin is phosphorylated by PINK1 to activate parkin. Nature. 2014;510:162–166. doi: 10.1038/nature13392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kane LA, Lazarou M, Fogel AI, Li Y, Yamano K, Sarraf SA, Banerjee S, Youle RJ. PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to activate Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. J Cell Biol. 2014;205:143–153. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201402104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kazlauskaite A, Kondapalli C, Gourlay R, Campbell DG, Ritorto MS, Hofmann K, Alessi DR, Knebel A, Trost M, Muqit MM. Parkin is activated by PINK1-dependent phosphorylation of ubiquitin at Ser65. Biochem J. 2014;460:127–139. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Narendra DP, Jin SM, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Gautier CA, Shen J, Cookson MR, Youle RJ. PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vives-Bauza C, Zhou C, Huang Y, Cui M, de Vries RL, Kim J, May J, Tocilescu MA, Liu W, Ko HS, Magrane J, Moore DJ, Dawson VL, Grailhe R, Dawson TM, Li C, Tieu K, Przedborski S. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:378–383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911187107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jin SM, Lazarou M, Wang C, Kane LA, Narendra DP, Youle RJ. Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates PINK1 import and proteolytic destabilization by PARL. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:933–942. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201008084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rigas S, Daras G, Laxa M, Marathias N, Fasseas C, Sweetlove LJ, Hatzopoulos P. Role of Lon1 protease in post-germinative growth and maintenance of mitochondrial function in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2009;181:588–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Farré JC, Manjithaya R, Mathewson RD, Subramani S. PpAtg30 tags peroxisomes for turnover by selective autophagy. Dev Cell. 2008;14:365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Motley AM, Nuttall JM, Hettema EH. Pex3-anchored Atg36 tags peroxisomes for degradation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 2012;31:2852–2868. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kirkin V, Lamark T, Sou YS, Bjorkoy G, Nunn JL, Bruun JA, Shvets E, McEwan DG, Clausen TH, Wild P, Bilusic I, Theurillat JP, Overvatn A, Ishii T, Elazar Z, Komatsu M, Dikic I, Johansen T. A role for NBR1 in autophagosomal degradation of ubiquitinated substrates. Mol Cell. 2009;33:505–516. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H, Overvatn A, Bjorkoy G, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24131–24145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Deosaran E, Larsen KB, Hua R, Sargent G, Wang Y, Kim S, Lamark T, Jauregui M, Law K, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Brech A, Johansen T, Kim PK. NBR1 acts as an autophagy receptor for peroxisomes. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:939–952. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Svenning S, Lamark T, Krause K, Johansen T. Plant NBR1 is a selective autophagy substrate and a functional hybrid of the mammalian autophagic adapters NBR1 and p62/SQSTM1. Autophagy. 2011;7:993–1010. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.9.16389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zientara-Rytter K, Lukomska J, Moniuszko G, Gwozdecki R, Surowiecki P, Lewandowska M, Liszewska F, Wawrzynska A, Sirko A. Identification and functional analysis of Joka2, a tobacco member of the family of selective autophagy cargo receptors. Autophagy. 2011;7:1145–1158. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.10.16617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dong C-H, Zolman BK, Bartel B, Lee B-h, Stevenson B, Agarwal M, Zhu J-K. Disruption of Arabidopsis CHY1 reveals an important role of metabolic status in plant cold stress signaling. Mol Plant. 2009;2:59–72. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rowe HC, Walley JW, Corwin J, Chan EK, Dehesh K, Kliebenstein DJ. Deficiencies in jasmonate-mediated plant defense reveal quantitative variation in Botrytis cinerea pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000861. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou J, Zhang Y, Qi J, Chi Y, Fan B, Yu JQ, Chen Z. E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP and NBR1-mediated selective autophagy protect additively against proteotoxicity in plant stress responses. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nordgren M, Francisco T, Lismont C, Hennebel L, Brees C, Wang B, Van Veldhoven PP, Azevedo JE, Fransen M. Export-deficient monoubiquitinated PEX5 triggers peroxisome removal in SV40 large T antigen-transformed mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Autophagy. 2015;11:1326–1340. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1061846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Burnett SF, Farré JC, Nazarko TY, Subramani S. Peroxisomal Pex3 activates selective autophagy of peroxisomes via interaction with the pexophagy receptor Atg30. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:8623–8631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.619338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Woodward AW, Bartel B. The Arabidopsis peroxisomal targeting signal type 2 receptor PEX7 is necessary for peroxisome function and dependent on PEX5. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:573–583. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-05-0422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pracharoenwattana I, Cornah JE, Smith SM. Arabidopsis peroxisomal malate dehydrogenase functions in β-oxidation but not in the glyoxylate cycle. Plant J. 2007;50:381–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Olsen LJ, Ettinger WF, Damsz B, Matsudaira K, Webb MA, Harada JJ. Targeting of glyoxysomal proteins to peroxisomes in leaves and roots of a higher plant. Plant Cell. 1993;5:941–952. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.8.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]