Abstract

Fear of negative evaluation has been documented as a mechanism that explains variations in feelings of belongingness. According to the interpersonal theory of suicide (Joiner, 2005), feelings of thwarted belongingness, that one does not belong, can significantly increase desire and risk for suicide. We proposed that differences in thwarted belongingness may explain variations in suicidal ideation and behavior as a function of levels of fear of negative evaluation. This hypothesis was tested by examining self-reported fears of negative evaluation, thwarted belongingness, and suicidal ideation in 107 young adults, many who were explicitly targeted for recruitment due to a history of suicidal ideation and behavior (13.1% had thoughts about suicide without a previous attempt; 15.9% reported at least one previous attempt [max = 5 attempts]). Mediation analyses were conducted with suicidal ideation entered as the outcome variable. Results indicated that greater fears of negative evaluation were significantly and positively associated with levels of suicidal ideation. Differences in thwarted belongingness fully accounted for the relationship between fears of negative evaluation and suicidal ideation. We conclude with clinical implications and future directions.

Keywords: suicidal ideation, fear of negative evaluation, thwarted belongingness, interpersonal theory of suicide

Previous research has shown that social anxiety symptoms, including fears of negative evaluation, are associated with increased risk for suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts (Nelson et al., 2000; Sareen et al., 2005). However, thus far, no research has examined mechanisms that may contribute to increased suicide risk in this population. Using the interpersonal theory of suicide as a guiding theoretical framework, this manuscript investigates one source of variation in suicide-related behaviors – thwarted belongingness. Given that the need to belong is a fundamental part of human existence (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), the interpersonal theory of suicide (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010) purports that suicide may be prevented when individuals feel socially connected, a sense of belongingness, and when belongingness is thwarted, significant increases in risk for suicidal ideation and behavior may occur (Van Orden et al., 2010). We explore variations in thwarted belongingness as an explanation for differences in suicidal ideation as a function of differences in levels of fear of negative evaluation, an essential aspect of social anxiety disorder. A greater understanding of the mechanisms contributing to increased suicide risk among individuals with high levels of fear of negative evaluation is important for treatment social anxiety disorder symptoms and the prevention of suicide.

Considerable research has documented an association between suicidal ideation and behavior and various indices of social isolation, including low social support (Qin & Nordentoft, 2005), loneliness (Koivumaa-Honkanen et al., 2001; Waern, Rubenowitz, & Wilhelmson, 2003), and living alone and/or unmarried (Conner, Duberstein, & Conwell, 1999; Cheng, Chen, Chen, & Jenkins, 2000; Stack, 2000). Moreover, individuals who die by suicide often experience social isolation and withdrawal prior to death (Robins, 1981; Trout, 1980). The interpersonal theory of suicide purports that these indices are associated with suicide across the lifespan as they indicate that the fundamental need to belong has been thwarted (Van Orden et al., 2010). Accordingly, studies have found that higher levels of thwarted belongingness are associated with greater suicide risk (e.g., Van Orden et al., 2010; Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012). Conversely, when belongingness is increased through situations that cause individuals to “pull together,” such as sporting events and national tragedies, declines in rates of death by suicide have been documented (Joiner, Hollar, & Van Orden, 2006). Taken together, these findings suggest that suicide rates may decrease when we increase belongingness by engendering a sense of community, and thwarted belongingness contributes to increased levels of suicidal ideation.

If thwarted belongingness is one explanation for variations in suicidal ideation, then variables influencing belongingness may evidence variation in suicidal ideation. One such variable that influences feelings of thwarted belongingness is fear of negative evaluation, which may be described as expectations of being evaluated negatively by others, looking foolish, or making a bad impression on others (Leary, 1983). Indeed, research has shown that fears of negative evaluation negatively contribute to social ability and are associated with decreased social skill, self-esteem, and sociability (Leary, 1983; Rapee & Heimberg, 1997). Reduced social ability contributes to greater fears of negative evaluation in social situations, resulting in a limited social network and greater feelings of loneliness (Rapee & Heimberg, 1997). Researchers have also found that lonely individuals, characterized by greater anxiety, less sociability, and poorer social skills, express stronger fears of negative evaluation (Cacioppo et al., 2000). Research directly examining these variables has shown indicated a significant, positive association between social anxiety symptoms and levels of thwarted belongingness (Davidson, Wingate, Grant, Judah, & Mills, 2011). In this study social anxiety did not predict suicidal ideation above and beyond feelings of thwarted belongingness (Davidson et al., 2011). This finding suggests that thwarted belongingness may be a more proximal predictor of suicidal ideation relative to social anxiety symptoms and thwarted belongingness may be a variable accounting for the relationship between social anxiety and suicide risk.

Overall, given that high levels of thwarted belongingness are related to greater fears of negative evaluation and suicidal ideation and behavior, higher levels of thwarted belongingness may account for the positive relationship between fears of negative evaluation, a core symptom of social anxiety disorder, and suicidal ideation and behavior. However, no studies, to the authors’ knowledge, have directly tested this hypothesis. In the present study, we investigated whether suicidal ideation in young adults will differ as a function of their fears of negative evaluation and analyzed the role that the thwarted belongingness plays in that variation. We hypothesized that thwarted belongingness will mediate the relationship between fears of negative evaluation and suicidal ideation.

Method

Participants

Participants were 107 young adults (34.8% male) recruited from the general undergraduate psychology subject pool at a large, southern, public university, many of who were explicitly targeted for recruitment due to elevated suicide risk (i.e., history of suicidal ideation and/or suicide attempts). Ages ranged from 18 to 35 years (M = 19.3, SD = 2.5). Participants were 74.8% Caucasian, 7% Black, 5.2% Asian, 0.9% American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 4.3% identified as Other; 7.8% did not report their race. Participants were primarily non-Hispanic (71.3%). Most participants reported no mental health diagnoses (90.5%) and the remainder acknowledged a history of a Mood Disorder (4.3%), Anxiety Disorder (2.9%), and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (1.9%); 1.7% reported a comorbid Eating Disorder. Participants varied as a function of their history of suicide-related behaviors (see below for recruitment strategy aimed to increase the number of participants with a history of suicidal ideation and behavior): 71.0% had never attempted or thought about suicide (n = 76), 13.1% had prior thoughts about suicide without a previous attempt (n = 14), and 15.9% reported at least one previous suicide attempt (n = 17, maximum = 5 attempts). Among the 17 individuals with a history of suicide attempts, 10 had a history of one previous suicide attempt and 7 had a history of multiple suicide attempts. Notably, rates of suicidal ideation and behavior are higher relative to the rates reported in a large survey conducted by the American College Health Association (2014), which reported that 9% of college students had a history of at least one suicide attempt, and 7.5% seriously considered suicide in the last 12-months.

Procedure

Data for this study were collected as part of a larger study on the autobiographical memory perspectives of individuals with and without a history of suicidal ideation and behavior (Chu, Buchman-Schmitt, & Joiner, in press). All participants completed an online screening questionnaire that was available to all undergraduate students. The screening questionnaire included two items assessing their history of suicidal ideation and behaviors. The first item assessed the number of previous suicide attempts, and the second assessed for suicidal ideation and the formation of plans for suicide. Although all individuals, regardless of their lifetime history of suicidal ideation and behavior, were invited to participate, individuals whose responses to the screening questionnaire suggest a history of suicide attempts or suicidal ideation were prompted to participate by e-mail (n = 118). The study procedures were in accordance with guidelines set forth by the university Institutional Review Board. Individuals presenting with cognitive impairments or language barriers that preclude the provision of informed consent were excluded; no participants were ineligible.

Eligible participants first reviewed and signed a statement of informed consent detailing the Human Subjects Committee approval, as well as the purpose, procedures, and goals of the study. Participants completed self-report questionnaires; only questionnaires relevant to the current study analyses will be detailed below (see Measures). Experimenters screened all participants’ responses to suicide-related questions to assess for severe and imminent suicide risk. All participants were debriefed and provided with mental health resources.

Measures

First, all participants completed brief self-reported questionnaires assessing demographic variables (e.g., age, gender) and suicide-related behaviors, including the number of previous suicide attempts. Subsequently, participants all completed the following questionnaires, which took approximately 15 minutes.

Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale (BFNE; Leary, 1983)

This scale measures apprehension about, avoidance of, and expectations regarding negative evaluation. It contains 12 items rated on 6-point Likert scales ranging from 0 = "not at all characteristic of me" to 5 = "extremely characteristic of me." Reliability and validity for this scale has been established in undergraduate populations (Leary, 1983; Weeks et al., 2005). In the present study, reliability was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = .91).

Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire - Belongingness (INQ-B; Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012)

The INQ is a 15-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure participants’ connection to others (i.e., belongingness) and the extent to which they feel like a burden on the people in their lives (i.e., perceived burdensomeness). Nine items on the INQ are indicators of thwarted belongingness. Higher values indicate more severe symptoms of thwarted belongingness. There is evidence for construct validity and good internal consistency in a non-clinical sample (thwarted belongingness items, α = .85; Van Orden et al., 2008; 2012). In the present study, reliability of the thwarted belongingness scale was excellent (Cronbach’s alpha = .91).

Depressive Symptom Inventory-Suicidality Subscale (DSI-SS; Metalsky & Joiner, 1997)

The DSI-SS is a 4-item self-report measure designed to assess the frequency and intensity of suicidal thoughts and impulses in the previous two weeks. Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3 with total scores range from 0 to 12; higher scores reflect an increased severity of current suicidal ideation. Prior studies have reported good validity and reliability for this measure (α = .90; Joiner, Pfaff, & Acres, 2002). In the present study, reliability of the DSI-SS was good (Cronbach’s alpha = .80).

Statistical Approach

All analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 22. Missing data, which were minimal (< 2%), were addressed using full maximum likelihood estimation. A post-hoc power analysis for the present study conducted using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007) indicated sufficient power (.95) to detect effects. Univariate ANOVAs were conducted to compare individuals with varying suicidal ideation and attempt histories across main study variables. The bootstrap technique recommended by Shrout and Bolger (2002) was used to test for the mediating effects of thwarted belongingness on the relationship between fear of negative evaluation and suicidal ideation (DSI-SS total score). Meditational analyses were conducted using the MEDIATE macro for SPSS, following procedures by Hayes and Preacher (2014).. Given previous research indicating that age and gender differences in suicidal ideation and behavior (Beautrais, 2001; Van Orden et al., 2010), in all analyses, age and gender were entered as covariates.

Results

Multicollinearity was examined for all regression equations; tolerance and variance inflation factor values were within acceptable range (>.10 or <10, respectively). Suppression was also examined for all regression equations; beta values were within acceptable range (Beta < zero-order correlation). One variable, DSI-SS total score (S = 2.83), exhibited significant positive skew. To address the skew, square root transformations were used. This decreased the skew from 2.83 to 2.21. Given that significant skew remained, log transformations were used and this decreased the skew from 2.21 to 1.68. Univariate outliers (median +/− 2 interquartile ranges) were identified for thwarted belongingness. Outliers were addressed by bringing the score in question to the next highest value within two interquartile ranges. No bivariate outliers were identified. Of note, analyses were conducted with the outliers included and the pattern of findings remained the same.

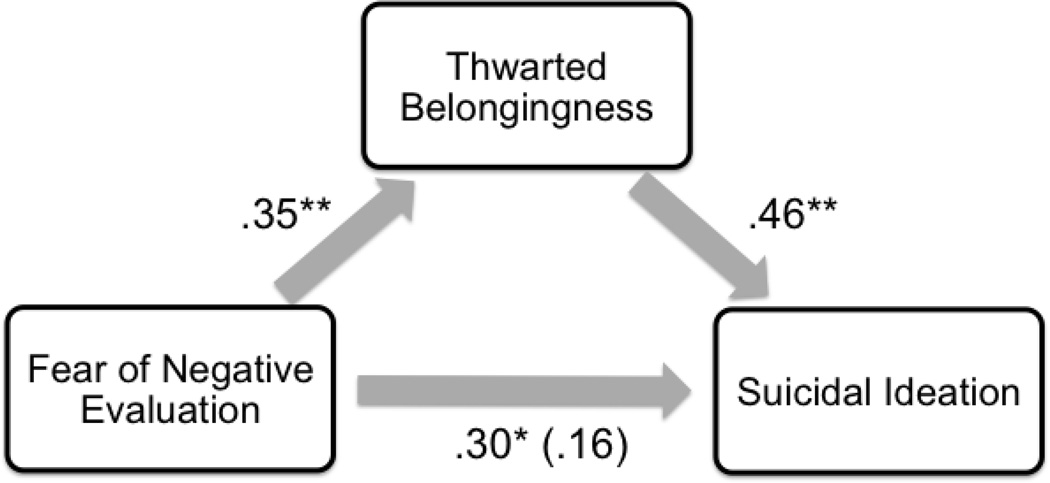

Means, standard errors of main study variables and group differences are provided in Table 1. Low to moderately strong, positive correlations emerged between fear of negative evaluation and thwarted belongingness (r = .35, p <.001) and suicidal ideation (r = .30, p =.002). As expected, thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation exhibited a stronger, moderate correlation (r = .46, p <.001).

Table 1.

Study variable means (standard error of the mean)

| Total N = 107 |

Controls n = 74 |

Suicide Ideators n = 14 |

Suicide Attempters n = 17 |

F | df | p | η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 19.3 (.24) |

19.0 | 19.5 | 20.2 | 1.71 | 2 | .19 | -- |

| # of previous suicide attempts |

.25 (.04) |

0 | 0 | 1.53 | 84.97 | 2 | <.001 | .62 |

| Suicidal ideation (DSI-SS) |

.39 (.10) |

.12 (.05) | .75 (.37) |

1.43 (.47) | 11.32 | 2 | <.001 | .20 |

| Fear of negative evaluation (BFNE) |

37.42 (1.00) |

36.69 (1.10) |

36.14 (3.20) |

42.06 (2.83) |

1.99 | 2 | .14 | -- |

| Thwarted belongingness (INQ- B) |

21.37 (1.09) |

18.96 (1.01) |

26.43 (4.00) |

28.25 (3.52) |

6.86 | 2 | .002 | .12 |

Note. DSI-SS = Depressive Symptom Inventory-Suicidality Subscale total score. BFNE = Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale total score. INQ-B = Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire – Belongingness Subscale score. N ranged from 105–107 due to missing variables. Univariate ANOVAs were conducted to examine group differences.

Fears of Negative Evaluation and Suicidal Ideation

The significance of the indirect effects of fear of negative evaluation on suicidal ideation (measured by the DSI-SS) through thwarted belongingness was evaluated using a bootstrapping resampling procedure: 5,000 bootstrapped samples were drawn from the data and bias corrected 95% confidence intervals (BCCI) in order to estimate the indirect effect for each of the resampled data sets (Preacher & Hayes, 2014; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). The paths from fear of negative evaluation (IV) to thwarted belongingness (M), and suicidal ideation (DV), and the paths from thwarted belongingness to suicidal ideation, were all significant. The indirect effect of fears of negative evaluation on suicidal ideation through thwarted belongingness was also significant (.009), and the 95% confidence interval (CI) ranged from .0027, .0187 (see Figure 1). As predicted, the direct effect of fears of negative evaluation on suicidal ideation was no longer significant after accounting for the effects of thwarted belongingness (p = .14), indicating that thwarted belongingness fully mediated the effects of fear of negative evaluation on suicidal ideation. 1

Figure 1.

** p <.001, * p < .01. Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between fear of negative evaluation and suicidal ideation as mediated by thwarted belongingness. The standardized regression coefficient between fear of negative evaluation and suicidal ideation, controlling for thwarted belongingness, is in parentheses. The indirect effect of fears of negative evaluation on suicidal ideation through thwarted belongingness was significant (.009), and the 95% confidence interval ranged from .0027, .0187.

Discussion

The present study provides support for an association between fear of negative evaluation and suicidal ideation. These findings suggest that feelings of thwarted belongingness fully account for this relationship. Given the results of the present study it may be argued that fear of negative evaluation is associated with greater feelings of thwarted belongingness, and thus, increased levels of suicidal ideation. Findings from the field of social psychology support this assumption. Maner, DeWall, Baumeister, and Schaller (2007) demonstrated that fear of negative evaluation moderated the effect of social exclusion on interpersonal reconnection efforts. Specifically, they found that individuals high on fear of negative evaluation did not exhibit the positive affiliation bias observed in individuals low on fear of negative evaluation. Thus, Maner and colleagues (2007) suggest that individuals high on negative fear of evaluation may be at greater risk of social isolation. The present study extends the results of Maner et al. (2007) by demonstrating that individuals high on fear of negative evaluation experience greater feelings of thwarted belongingness, thus suggesting that these individuals desire, yet lack meaningful social connections. Furthermore, our results suggest that such individuals are more prone to suicidal thoughts than those with low fear of negative evaluation.

An alternative, yet compatible interpretation of the present results is that the participants high on fear of negative evaluation exhibit an interpretation bias, wherein they are more prone to interpret neutral social situations as threatening. Negative interpretation biases have been observed in individuals with social anxiety disorder (Stopa & Clark, 2000) and research has demonstrated that individuals with social anxiety are at increased risk for suicide (Sareen et al., 2005). Given that the tendency to interpret neutral social stimuli as threatening is associated with decreased social activity (Kimbrel, 2008), it may be suggested that such interpretations biases and their associated behavioral responses increase feelings of thwarted belongingness, and possibly, suicidal desire. However, future research investigating the relationship between interpretation biases, thwarted belongingness, and suicidal ideation and behavior is needed to test this hypothesis.

Congruent with the interpersonal theory of suicide and the need to belong theory, our findings provide further evidence for the importance of belongingness in the maintenance of psychological health. Therefore, clinicians treating patients simultaneously presenting with symptoms of social anxiety, particularly fears of negative evaluation, and suicidal ideation should consider targeting thwarted belongingness in treatment. To this end, a cognitive behavioral approach may be useful. For example, clinicians may challenge distorted cognitions regarding previous situations where they felt disconnected with others and help patients identify more helpful thoughts (e.g., “No one cares about me,” to “My sister calls regularly and cares about me;” Stellrecht et al., 2006). Clinicians may also encourage patients to identify and incorporate activities that increase the patient’s sense of interpersonal connection with others (Stellrecht et al., 2006). Moreover, patients presenting with symptoms of social anxiety may avoid social activities as a result of fears of negative evaluation in social situations. Over time, social avoidance may lead to a diminished network of social support, which may increase feelings of thwarted belongingness. For this reason, clinicians treating social anxiety should monitor patients’ feelings of connection to others throughout treatment as high levels of thwarted belongingness may lead to increases in suicidal ideation. Inquiries regarding a patient’s social support network, levels of social involvement, and any recent interpersonal losses may be useful for evaluating levels of thwarted belongingness (Stellrecht et al., 2006). Assessments of suicide risk should be conducted regularly when treating patients with social anxiety symptoms and high levels of thwarted belongingness.

Limitations and Future Directions

Findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, while recent statistics suggest that young adults are particularly vulnerable to suicide (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012), this sample was comprised primarily of young females in college and caution is warranted when generalizing beyond young adult populations. Additionally, previous research indicating that individuals diagnosed with social anxiety disorder not only have higher levels of fear of negative evaluation (Rapee & Heimberg, 1997), but also higher odds for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts over the course of their lifetime (Thibodeau, Welch, Sareen, & Asmundson, 2013). Further, this study employed a cross-sectional approach and relied on self-report measures of suicidal ideation and behavior, which prevents any inferences of causality. As such, future research evaluating these variables using a longitudinal approach and structured clinical assessments of suicide-related behaviors in a clinical population would be particularly informative. Moving forward, more research is needed to evaluate how fears of negative evaluation might confer risk of suicidal ideation and behavior. Future research examining other psychological features of social anxiety disorder (e.g., hypersensitivity to criticism, negative interpretation biases) will be vital for furthering our understanding of the nature the relationship between social anxiety disorder and suicide.

Notably, although the base rates of suicidal ideation and behavior are relatively low, this study specifically targeted young adults, many with a history of suicidal ideation and/or attempts and are at increased suicide risk. As a result, the present findings provide valuable information about individuals at increased risk for suicide in the college population. This study was the first to empirically test previous conjectures regarding the mediating role of thwarted belongingness in the relationship between fear of negative evaluation, a core feature of social anxiety disorder and suicidal ideation. We look forward to future studies replicating and extending our understanding of the factors contributing to the relationship between anxiety and suicidal ideation and behavior.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Of note, these data have not been previously presented elsewhere.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the university’s institutional research board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

In order to internally replicate the DSI-SS findings, the bootstrapping resampling procedure was used to test the significance of the indirect effects of fear of negative evaluation on self-reported suicide attempt history (0 = controls, 1 = current ideators with no history of suicide attempts, 2 = current ideators with a history of at least one suicide attempt) via the mediator, thwarted belongingness. The indirect effect of fears of negative evaluation on self-reported suicide attempt history through thwarted belongingness was significant (.0085); the 95% CI ranged from .0024, .0186. As predicted, the direct effect of fear of negative evaluation on self-reported suicide attempt history was no longer significant after accounting for the effects of thwarted belongingness (p =.59), indicating that thwarted belongingness fully mediated the relationship between fear of negative evaluation and self-reported suicide attempt history.

References

- American College Health Association. National College Health Assessment II: Reference group executive summary, fall 2013. Baltimore, MD: American College Health Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(3):497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beautrais AL. Suicides and serious suicide attempts: two populations or one? Psychological Medicine. 2001;31(05):837–845. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Ernst JM, Burleson MH, McClintock MK, Malarkey WB, Hawkley LC, Berntson GG. Lonely traits and concomitant physiological processes: the MacArthur social neuroscience studies. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2000;35(2):143–154. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(99)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide: Facts at a Glance. 2012 Sep 25; Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pub/suicide_datasheet.html.

- Cheng AT, Chen TH, Chen CC, Jenkins R. Psychosocial and psychiatric risk factors for suicide Case-control psychological autopsy study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177(4):360–365. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.4.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Joiner TE. Autobiographical memory perspectives in task and suicide attempt recall: A study of young adults with and without symptoms of suicidality. Cognitive Therapy and Research. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Duberstein PR, Conwell Y. Age-related patterns of factors associated with completed suicide in men with alcohol dependence. The American Journal on Addictions. 1999;8:312–318. doi: 10.1080/105504999305712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson CL, Wingate LR, Grant DM, Judah MR, Mills AC. Interpersonal suicide risk and ideation: The influence of depression and social anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2011;30(8):842–855. [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Preacher KJ. Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 2014;67:451–470. doi: 10.1111/bmsp.12028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Hollar D, Orden KV. On Buckeyes, Gators, Super Bowl Sunday, and the Miracle on Ice: “Pulling together” is associated with lower suicide rates. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25(2):179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Pfaff JJ, Acres JG. A brief screening tool for suicidal symptoms in adolescents and young adults in general health settings: reliability and validity data from the Australian National General Practice Youth Suicide Prevention Project. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40(4):471–481. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA. A model of the development and maintenance of generalized social phobia. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(4):592–612. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Honkanen R, Viinamäki H, Heikkilä K, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M. Life satisfaction and suicide: A 20-year follow-up study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:433–439. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maner JK, DeWall CN, Baumeister RF, Schaller M. Does social exclusion motivate interpersonal reconnection? Resolving the" porcupine problem". Journal of personality and social psychology. 2007;92(1):42–55. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EC, Grant JD, Bucholz KK, Glowinski A, Madden PAF, Reich W, Heath AC. Social phobia in a population-based female adolescent twin sample: co-morbidity and associated suicide-related symptoms. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30(04):797–804. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P, Nordentoft M. Suicide risk in relation to psychiatric hospitalization: evidence based on longitudinal registers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(4):427–432. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Heimberg RG. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35(8):741–756. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhemtulla M, Brosseau-Liard PÉ, Savalei V. When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological Methods. 2012;17(3):354–373. doi: 10.1037/a0029315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins E. The final months: A study of the lives of 134 persons who committed suicide. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, de Graaf R, Asmundson GJ, ten Have M, Stein MB. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):1249–1257. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NM, Pollack MH, Ostacher MJ, Zalta AK, Chow CW, Fischmann D, Otto MW. Understanding the link between anxiety symptoms and suicidal ideation and behaviors in outpatients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;97(1):91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stack S. Suicide: A 15-year review of the sociological literature part II: Modernization and social integration perspectives. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2000;30:163–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellrecht NE, Gordon KH, Van Orden K, Witte TK, Wingate LR, Cukrowicz KC, Fitzpatrick KK. Clinical applications of the interpersonal?psychological theory of attempted and completed suicide. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62(2):211–222. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopa L, Clark DM. Social phobia and interpretation of social events. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38(3):273–283. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibodeau MA, Welch PG, Sareen J, Asmundson GJ. Anxiety disorders are independently associated with suicide ideation and attempts: propensity score matching in two epidemiological samples. Depression and Anxiety. 2013;30(10):947–954. doi: 10.1002/da.22203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trout DL. The role of social isolation in suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1980;10:10–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278x.1980.tb00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, Joiner Jr TE. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24(1):197–215. doi: 10.1037/a0025358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner Jr TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review. 2010;117(2):575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, James LM, Castro Y, Gordon KH, Braithwaite SR, Joiner TE. Suicidal ideation in college students varies across semesters: The mediating role of belongingness. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38(4):427–435. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waern M, Rubenowitz E, Wilhelmson K. Predictors of suicide in the old elderly. Gerontology. 2003;49:328–334. doi: 10.1159/000071715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]