Abstract

BACKGROUND

Central sleep apnea is associated with poor prognosis and death in patients with heart failure. Adaptive servo-ventilation is a therapy that uses a noninvasive ventilator to treat central sleep apnea by delivering servo-controlled inspiratory pressure support on top of expiratory positive airway pressure. We investigated the effects of adaptive servo-ventilation in patients who had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and predominantly central sleep apnea.

METHODS

We randomly assigned 1325 patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 45% or less, an apnea–hypopnea index (AHI) of 15 or more events (occurrences of apnea or hypopnea) per hour, and a predominance of central events to receive guideline-based medical treatment with adaptive servo-ventilation or guideline-based medical treatment alone (control). The primary end point in the time-to-event analysis was the first event of death from any cause, lifesaving cardiovascular intervention (cardiac transplantation, implantation of a ventricular assist device, resuscitation after sudden cardiac arrest, or appropriate lifesaving shock), or unplanned hospitalization for worsening heart failure.

RESULTS

In the adaptive servo-ventilation group, the mean AHI at 12 months was 6.6 events per hour. The incidence of the primary end point did not differ significantly between the adaptive servo-ventilation group and the control group (54.1% and 50.8%, respectively; hazard ratio, 1.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.97 to 1.31; P = 0.10). All-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality were significantly higher in the adaptive servo-ventilation group than in the control group (hazard ratio for death from any cause, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.55; P = 0.01; and hazard ratio for cardiovascular death, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.65; P = 0.006).

CONCLUSIONS

Adaptive servo-ventilation had no significant effect on the primary end point in patients who had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and predominantly central sleep apnea, but all-cause and cardiovascular mortality were both increased with this therapy.

Sleep-disordered breathing is common in patients who have heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, with reported prevalence rates of 50 to 75%.1 Obstructive sleep apnea occurs more often in patients with heart failure than in the general population. Central sleep apnea, which may manifest as Cheyne–Stokes respiration, is found in 25 to 40% of patients who have heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.2 The prevalence of central sleep apnea increases in parallel with increasing severity of heart failure1 and worsening cardiac dysfunction.3

There are a number of mechanisms by which central sleep apnea may be detrimental to cardiac function, including increased sympathetic nervous system activity and intermittent hypoxemia.4–6 Central sleep apnea is an independent risk marker for poor prognosis and death in patients with heart failure.4,7,8

In the Canadian Continuous Positive Airway Pressure for Patients with Central Sleep Apnea and Heart Failure (CANPAP) study, patients with heart failure and central sleep apnea were randomly assigned to receive continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or no CPAP.9 The trial was stopped prematurely and did not show a beneficial effect of CPAP on morbidity or mortality. A post hoc analysis suggested that mortality might be lower if the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI; the number of occurrences of apnea or hypopnea per hour of sleep) is reduced to less than 15 events per hour.10

Adaptive servo-ventilation is a noninvasive ventilatory therapy that effectively alleviates central sleep apnea by delivering servo-controlled inspiratory pressure support on top of expiratory positive airway pressure.11,12 The Treatment of Sleep-Disordered Breathing with Predominant Central Sleep Apnea by Adaptive Servo Ventilation in Patients with Heart Failure (SERVE-HF) trial investigated the effects of adding adaptive servoventilation (AutoSet CS, ResMed) to guidelinebased medical treatment on survival and cardiovascular outcomes in patients who had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and predominantly central sleep apnea.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND OVERSIGHT

The SERVE-HF trial was an international, multicenter, randomized, parallel-group, event-driven study. Information about the study design has been reported previously.13 The trial was sponsored by ResMed. The study protocol, which is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org, was designed by the steering committee with the support of the scientific advisory board and was approved by the ethics committee at each study center. The trial was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the 2002 Declaration of Helsinki.

The steering committee oversaw the conduct of the trial and data analysis in collaboration with the sponsor according to a prespecified statistical analysis plan. The trial was reviewed by an independent data and safety monitoring committee. The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by the first three authors and the last author, who had unrestricted access to the data, with the assistance of an independent medical writer funded by the sponsor. The manuscript was reviewed and edited by all the authors. All the authors made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication and assume responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the analyses and for the fidelity of this report to the trial protocol.

STUDY PATIENTS

Patients were eligible for participation in the study if they were 22 years of age or older and had symptomatic chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Specific requirements included a left ventricular ejection fraction of 45% or less, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV heart failure or NYHA class II heart failure with at least one heart failure–related hospitalization within the 24 months before randomization, and stable, guideline-based medical treatment. Eligible participants also had predominantly central sleep apnea (AHI, ≥15 events per hour, with >50% central events [apnea or hypopnea] and a central AHI of ≥10 events per hour). Full details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org. All the participants provided written informed consent.

INTERVENTION

Adjustment of adaptive servo-ventilation was performed in the hospital with the use of polysomnographic or polygraphic monitoring. Default settings were used (expiratory positive airway pressure, 5 cm of water; minimum pressure support, 3 cm of water; and maximum pressure support, 10 cm of water). The expiratory positive airway pressure was increased manually to control obstructive sleep apnea, and the maximum pressure support was increased to control central sleep apnea. A full face mask was recommended for the initiation of adaptive servo-ventilation.

Patients were advised to use the adaptive servo-ventilation device for at least 5 hours per night, 7 days per week. Adherence to therapy was defined as the use of adaptive servo-ventilation for an average of at least 3 hours per night. The target was to reduce the AHI to less than 10 events per hour within 14 days after starting adaptive servo-ventilation.

FOLLOW-UP

Clinic visits took place at study entry, after 2 weeks, at 3 and 12 months, and every 12 months thereafter until the end of the study. Patients were contacted by telephone at 6 months and then at 12-month intervals. Patients in the adaptive servo-ventilation group also underwent polygraphy or polysomnography at each visit, and data were downloaded from the adaptive servo-ventilation device. Continual on-site monitoring was performed, with source-data verification of core data in all the patients. Central monitoring of documents (patients’ records and case-report forms) regarding serious adverse events was performed before the assessments by the end-point review committee. After the protocol-specified goal of 651 identified and adjudicated primary end points was met, the trial was terminated, and final visits were arranged for all the patients so that end-of-trial assessments could be performed and data regarding any remaining end points or adverse events could be collected before the database was locked.

END POINTS

The primary study end point in the time-to-event analysis was the first event of the composite of death from any cause, a lifesaving cardiovascular intervention, or an unplanned hospitalization for worsening chronic heart failure, with the latter two end-point events being assessed by the end-point review committee. Lifesaving cardiovascular intervention included cardiac transplantation, implantation of a long-term ventricular assist device, resuscitation after sudden cardiac arrest, or appropriate shock for ventricular arrhythmia in patients with an implantable cardioverter–defibrillator.

Subsequent hierarchical end points to be tested if the null hypothesis for the primary end point was rejected were the first secondary end point (which was the same as the primary end point but included cardiovascular death instead of death from any cause) and the second secondary end point (which was the same as the primary end point but included unplanned hospitalization for any cause instead of unplanned hospitalization related to heart failure) (see the Supplementary Appendix). Additional secondary end points were the time to death from any cause, the time to death from cardiovascular causes, and change in NYHA class and change in the 6-minute walk distance (both as assessed at follow-up visits).

Quality of life was assessed with the use of three instruments. Changes in general quality of life were measured with the use of the EuroQol Group 5-Dimension Self-Report Questionnaire (EQ-5D). Changes in disease-specific quality of life were measured with the use of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire. The effect of sleep apnea on daytime sleepiness was measured with the use of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (on which scores range from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating more daytime sleepiness).

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The study was designed to show a 20% reduction in the rate of the first primary end-point event with adaptive servo-ventilation. We calculated that data on 651 events had to be collected for the study to have a power of 80% to show that reduction, at an overall two-sided type I error rate of 5%. Because recruitment was slower than scheduled and the pooled event rate was below the expected rate in two blinded interim analyses, the required sample size was adapted twice, with a planned total of 1193 patients to be recruited over a period of 60 months, plus an additional 2 years of follow-up. Recruitment continued for longer than planned owing to a delay with an associated substudy, which resulted in the recruitment of more than 1193 patients. The target number of 651 observed events was never changed.

The primary analysis was conducted in the intention-to-treat population, which consisted of all the patients who underwent randomization, with adjudication of all the events that occurred before the database was locked. The analysis followed a group-sequential design with two interim analyses with O’Brien–Fleming stopping boundaries and two-sided log-rank tests comparing the control group with the adaptive servo-ventilation group. The significance level of the final analysis step was 0.0430, and the corresponding rejection boundary of the standardized log-rank statistic was ±2.024, keeping an overall two-sided significance level of 5%. The excess of events at the termination of the trial was included in the final analysis with the use of the inverse normal method (a combination rule for interim tests that does not require equal sample sizes of the interim intervals). Cause-specific hazard ratios were calculated, and cumulative incidence curves that can take potential competing risks into account were used to visualize survival data. Further details regarding the statistical analysis, including analyses of the secondary end points and sensitivity analyses, are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

RESULTS

STUDY PATIENTS

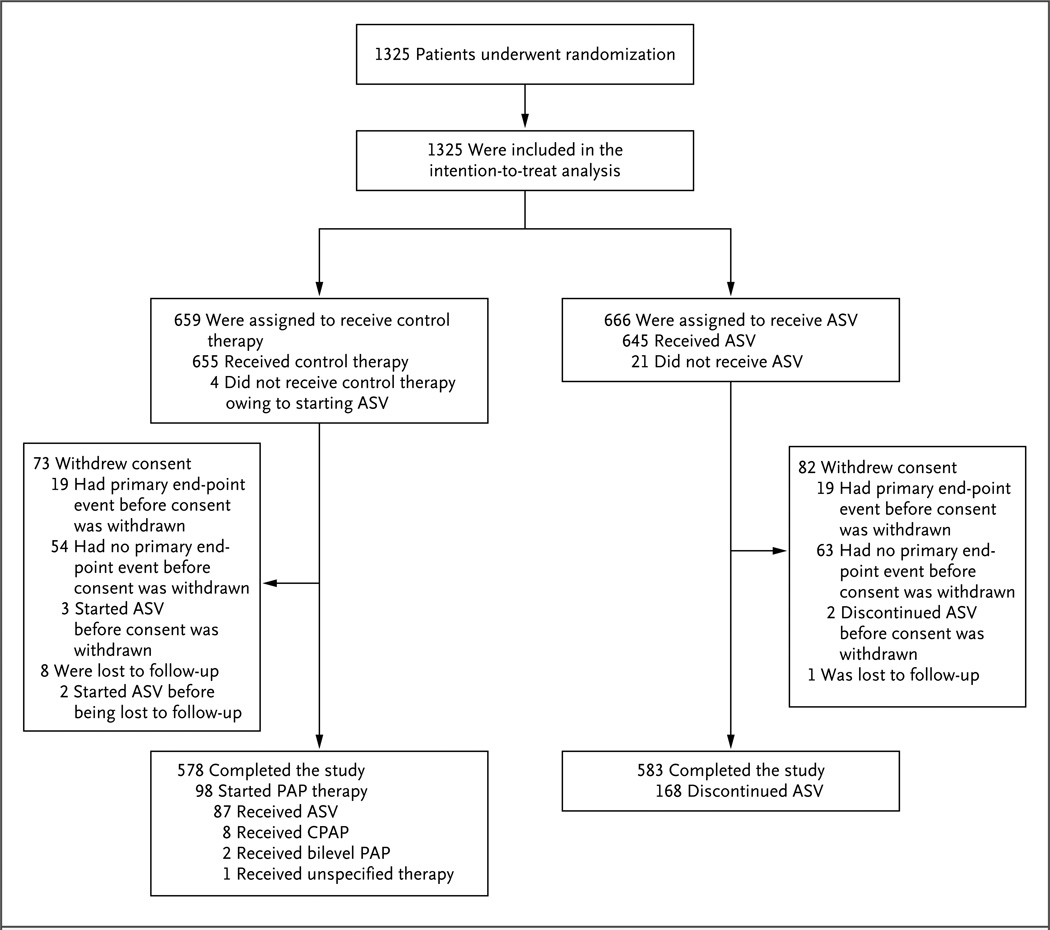

A total of 1325 patients were enrolled from February 2008 through May 2013 at 91 centers and were included in the intention-to-treat analysis; 659 patients were assigned to the control group and 666 to the adaptive servo-ventilation group (Fig. 1). Information regarding patient withdrawals, follow-up, and the handling of missing data is provided in the Supplementary Appendix. Table 1 provides details regarding the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients in the two study groups at baseline; the countries of enrollment are listed in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the control group and the adaptive servo-ventilation group, except for the rate of antiarrhythmic drug use, which was higher in the adaptive servo-ventilation group than in the control group (P = 0.005) (Table 1). The respiratory characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1. Randomization, Treatment, and Follow-up of the Patients.

Patients who withdrew consent did so for both study participation and follow-up (see the Supplementary Appendix). Of the 73 patients who withdrew consent in the control group, 3 had started adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV), and of the 82 who withdrew consent in the ASV group, 2 had discontinued ASV. CPAP denotes continuous positive airway pressure, and PAP positive airway pressure.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline.*

| Characteristic | Control (N = 659) |

Adaptive Servo-Ventilation (N = 666) |

|---|---|---|

| Age — yr | 69.3±10.4 | 69.6±9.5 |

| Male sex — no. (%) | 599 (90.9) | 599 (89.9) |

| Body weight — kg | 86.1±17.5 | 85.6±15.8 |

| Body-mass index† | 28.6±5.1 | 28.4±4.7 |

| NYHA class — no./total no. (%) | ||

| II | 194/654 (29.7) | 195/662 (29.5) |

| III | 454/654 (69.4) | 456/662 (68.9) |

| IV | 6/654 (0.9) | 11/662 (1.7) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction — %‡ | ||

| Mean | 32.5±8.0 | 32.2±7.9 |

| Range | 9.0–71.0 | 10.0–54.0 |

| Diabetes mellitus — no./total no. (%) | 252/653 (38.6) | 254/660 (38.5) |

| Cause of heart failure — no./total no. (%) | ||

| Ischemic | 366/642 (57.0) | 390/653 (59.7) |

| Nonischemic | 276/642 (43.0) | 263/653 (40.3) |

| Blood pressure — mm Hg | ||

| Systolic | 122.1±19.6 | 122.3±19.0 |

| Diastolic | 73.3±11.5 | 73.7±11.3 |

| Electrocardiographic finding — no./total no. (%) | ||

| Left bundle-branch block§ | 65/295 (22.0) | 79/304 (26.0) |

| Sinus rhythm | 395/646 (61.1) | 372/650 (57.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 147/646 (22.8) | 178/650 (27.4) |

| Other | 104/646 (16.1) | 100/650 (15.4) |

| Implanted device — no. (%) | 364 (55.2) | 362 (54.4) |

| No device | 295 (44.8) | 304 (45.6) |

| Non-CRT pacemaker | 29 (4.4) | 32 (4.8) |

| ICD | 161 (24.4) | 163 (24.5) |

| CRT-P | 21 (3.2) | 14 (2.1) |

| CRT-D | 153 (23.2) | 153 (23.0) |

| Hemoglobin — g/dl | 13.9±1.5 | 13.8±1.6 |

| Creatinine — mg/dl¶ | 1.4±0.6 | 1.4±0.6 |

| Estimated GFR — ml/min/1.73 m2 | 59.3±20.8 | 57.8±21.1 |

| 6-Min walk distance — m | 337.9±127.5 | 334.0±126.4 |

| Concomitant cardiac medication — no./total no. (%) | ||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 603/659 (91.5) | 613/666 (92.0) |

| Beta-blocker | 611/659 (92.7) | 612/666 (91.9) |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 325/659 (49.3) | 316/666 (47.4) |

| Diuretic | 561/659 (85.1) | 561/666 (84.2) |

| Cardiac glycoside | 124/657 (18.9) | 149/666 (22.4) |

| Antiarrhythmic drug | 89/659 (13.5) | 128/666 (19.2) |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. There were no significant differences between the control group and the adaptive servo-ventilation group, except for the rate of antiarrhythmic drug use, which was higher in the adaptive servo-ventilation group than in the control group (P = 0.005). Data were missing for the following characteristics: body weight, for 8 patients in the control group and 9 in the adaptive servo-ventilation group; body-mass index, for 8 and 9, respectively; left ventricular ejection fraction, for 126 and 130, respectively; systolic blood pressure, for 15 and 11, respectively; diastolic blood pressure, for 15 and 12, respectively; hemoglobin, for 27 and 25, respectively; creatinine level, for 30 and 29, respectively; and 6-minute walk distance, for 41 and 34, respectively.

ACE denotes angiotensin-converting–enzyme, ARB angiotensin-receptor blocker, CRT cardiac-resynchronization therapy, CRT-D CRT with defibrillator function, CRT-P CRT with pacemaker function, GFR glomerular filtration rate, ICD implantable cardioverter–defibrillator, and NYHA New York Heart Association.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

The measurement of left ventricular ejection fraction was added to the study protocol 32 months after the first patient underwent randomization.

Left bundle-branch block was assessed in patients who did not have an implanted device.

To convert the values for creatinine to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4.

Table 2.

Respiratory Characteristics at Baseline.*

| Characteristic | Control (N = 659) |

Adaptive Servo-Ventilation (N = 666) |

|---|---|---|

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale score† | 7.1±4.6 | 7.0±4.3 |

| AHI — no. of events/hr | 31.7±13.2 | 31.2±12.7 |

| Central apnea index/total AHI — % | 46.5±30.0 | 44.6±28.9 |

| Central AHI/total AHI — % | 81.8±15.7 | 80.8±15.5 |

| Oxygen desaturation index — no. of events/hr‡ | 32.8±19.0 | 32.1±17.7 |

| Oxygen saturation — % | ||

| Mean | 92.8±2.5 | 92.8±2.3 |

| Minimum | 80.3±7.5 | 80.7±7.0 |

| Time with oxygen saturation <90% — min | 55.7±73.9 | 50.5±68.2 |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD. There were no significant differences between the control group and the adaptive servo-ventilation group. Data were missing for the following characteristics: Epworth Sleepiness Scale score, for 8 patients in the control group and 13 in the adaptive servo-ventilation group; the apnea–hypopnea index (AHI; the number of occurrences of apnea or hypopnea per hour), for 1 in the adaptive servo-ventilation group; central apnea index divided by the total AHI, for 2 in the adaptive servo-ventilation group; central AHI divided by the total AHI, for 1 in the adaptive servo-ventilation group; mean oxygen desaturation index, for 4 in the control group and 7 in the adaptive servo-ventilation group; average oxygen saturation, for 3 in the adaptive servo-ventilation group; minimum oxygen saturation, for 5 in the adaptive servo-ventilation group; and time with an oxygen saturation of less than 90%, for 3 in the control group and 10 in the adaptive servo-ventilation group.

Scores on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale range from 0 to 24, with higher scores indicating more daytime sleepiness.

The oxygen desaturation index is the number of times per hour of recording that the blood oxygen level drops by ≥3 percentage points from baseline.

STUDY INTERVENTION AND FOLLOW-UP

The median duration of follow-up was 31 months (range, 0 to 80). We assessed the median positive airway pressure values at each time point and then calculated the mean of the median values (i.e., mean median values). In the adaptive servo-ventilation group, the device-measured mean median values of expiratory positive airway pressure were 5.5 cm of water (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.4 to 5.6) at baseline and 5.7 cm of water (95% CI, 5.6 to 5.8) at 12 months; the device-measured mean median values of inspiratory positive airway pressure were 9.7 cm of water (95% CI, 9.6 to 9.8) at baseline and 9.8 cm of water (95% CI, 9.6 to 9.9) at 12 months. Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix lists additional device-measured data.

A total of 60% of the patients in the adaptive servo-ventilation group used adaptive servo-ventilation for an average of 3 hours per night or more during the trial period (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). Sleep-disordered breathing was well controlled during adaptive servo-ventilation therapy. At 12 months, the mean AHI was 6.6 events per hour, and the oxygen desaturation index (the number of times per hour of recording that the blood oxygen level drops by ≥3 percentage points from baseline) was 8.6 events per hour (Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix).

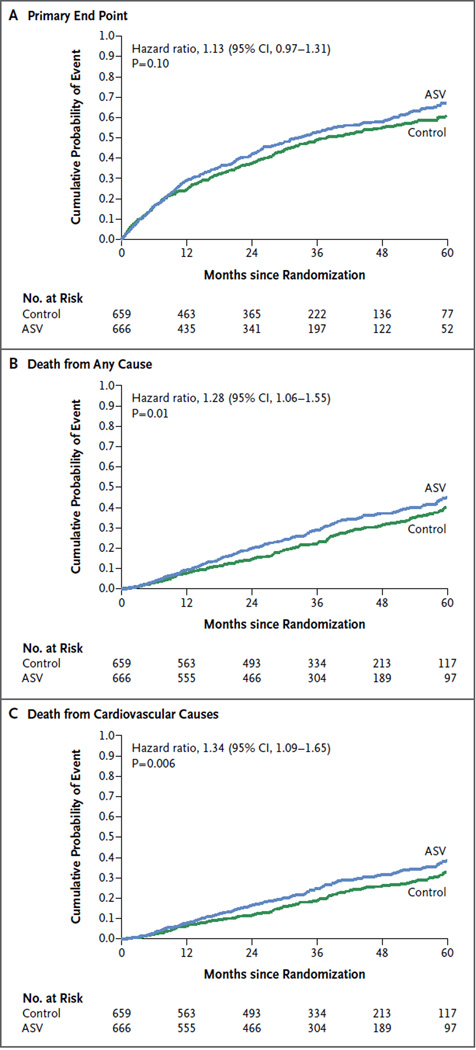

SURVIVAL AND CARDIOVASCULAR END POINTS

A summary of end-point events according to treatment group is provided in Table 3. The incidence of the primary end point did not differ significantly between the adaptive servo-ventilation group and the control group, with event rates of 54.1% and 50.8%, respectively (hazard ratio, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.31; P = 0.10) (Fig. 2A). Because the first and second secondary end points were prespecified to be analyzed hierarchically only if the null hypothesis for the primary end point was rejected, the results of those analyses are considered to be exploratory. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to either of these end points.

Table 3.

Incidence of End-Point Events.*

| Event | Control (N = 659) |

Adaptive Servo-Ventilation (N = 666) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients (%) |

No. of Events/Yr (95% CI) |

No. of Patients (%) |

No. of Events/Yr (95% CI) |

|||

| Primary end point† | 335 (50.8) | 0.212 (0.190–0.236) |

360 (54.1) | 0.245 (0.220–0.272) |

1.13 (0.97–1.31) |

0.10 |

| First secondary end point† | 317 (48.1) | 0.200 (0.179–0.224) |

345 (51.8) | 0.235 (0.211–0.261) |

1.15 (0.98–1.34) |

0.08 |

| Second secondary end point† | 465 (70.6) | 0.405 (0.369–0.444) |

482 (72.4) | 0.441 (0.403–0.483) |

1.07 (0.94–1.22) |

0.28 |

| Death from any cause | 193 (29.3) | 0.093 (0.081–0.107) |

232 (34.8) | 0.119 (0.104–0.135) |

1.28 (1.06–1.55) |

0.01 |

| Cardiovascular death | 158 (24.0) | 0.076 (0.065–0.089) |

199 (29.9) | 0.102 (0.088–0.117) |

1.34 (1.09–1.65) |

0.006 |

| Hospitalization for any cause | 448 (68.0) | 0.384 (0.349–0.421) |

452 (67.9) | 0.411 (0.374–0.451) |

1.05 (0.92–1.20) |

0.47 |

| Unplanned hospitalization for worsening heart failure | 272 (41.3) | 0.164 (0.145–0.185) |

287 (43.1) | 0.190 (0.169–0.214) |

1.13 (0.95–1.33) |

0.16 |

| Heart transplantation | 12 (1.8) | 0.006 (0.003–0.010) |

8 (1.2) | 0.004 (0.002–0.008) |

0.70 (0.28–1.70) |

0.43 |

| Implantation of long-term VAD | 10 (1.5) | 0.005 (0.002–0.009) |

16 (2.4) | 0.008 (0.005–0.013) |

1.67 (0.76–3.68) |

0.20 |

| Resuscitation | 19 (2.9) | 0.009 (0.006–0.014) |

25 (3.8) | 0.013 (0.008–0.019) |

1.40 (0.77–2.54) |

0.27 |

| Resuscitation for cardiac arrest | 16 (2.4) | 0.008 (0.004–0.013) |

18 (2.7) | 0.009 (0.005–0.015) |

1.19 (0.61–2.34) |

0.61 |

| Appropriate shock | 65 (9.9) | 0.033 (0.026–0.043) |

45 (6.8) | 0.024 (0.017–0.032) |

0.71 (0.48–1.04) |

0.08 |

| Noncardiovascular death | 35 (5.3) | 0.017 (0.012–0.024) |

33 (5.0) | 0.017 (0.012–0.024) |

1.00 (0.62–1.62) |

0.99 |

VAD denotes ventricular assist device.

The primary study end point in the time-to-event analysis was the first event of death from any cause, lifesaving cardiovascular intervention (cardiac transplantation, implantation of a long-term ventricular assist device, resuscitation after sudden cardiac arrest, or appropriate shock for ventricular arrhythmia in patients with an ICD), and unplanned hospitalization for worsening chronic heart failure. The first secondary end point was the same as the primary end point, but with cardiovascular death instead of death from any cause. The second secondary end point was the same as the primary end point, but with unplanned hospitalization for any cause instead of unplanned hospitalization related to heart failure.

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence Curves for the Primary End Point, Death from Any Cause, and Cardiovascular Death.

The primary end point was a composite of death from any cause, lifesaving cardiovascular intervention (cardiac transplantation, implantation of a long-term ventricular assist device, resuscitation after sudden cardiac arrest, or appropriate shock for ventricular arrhythmia in patients with an implantable cardioverter–defibrillator), and unplanned hospitalization for worsening chronic heart failure.

All-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality were higher in the adaptive servo-ventilation group than in the control group. All-cause mortality was 34.8% and 29.3%, respectively (hazard ratio for death from any cause, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.55; P = 0.01), and cardiovascular mortality was 29.9% and 24.0%, respectively (hazard ratio for death from cardiovascular causes, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.65; P = 0.006) (Fig. 2B and 2C). Similar findings were noted in the sensitivity analyses of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality (Tables S5 and S6 and Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix).

SUBGROUP ANALYSES

Subgroup analyses were conducted for the primary end point and for cardiovascular mortality. In the analysis of the primary end point, there was a significant modification of effect by the degree of Cheyne–Stokes respiration, and in the analysis of cardiovascular mortality, there was a significant modification of effect by the left ventricular ejection fraction (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix).

SYMPTOMS AND QUALITY OF LIFE

Assessments performed with the use of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire, the EQ-5D, and the NYHA classification showed no significant differences between the adaptive servo-ventilation group and the control group during the study (Figs. S3, S4, and S5 in the Supplementary Appendix). Although the Epworth Sleepiness Scale score decreased in the two study groups, the change was significantly greater in the adaptive servo-ventilation group (P<0.001) (Fig. S6 in the Supplementary Appendix). There was a gradual decline in the 6-minute walk distance in both the control group and the adaptive servo-ventilation group, but the decline was significantly more pronounced in the adaptive servo-ventilation group (P = 0.02) (Fig. S7 in the Supplementary Appendix).

DISCUSSION

The SERVE-HF study showed that although adaptive servo-ventilation therapy effectively treated central sleep apnea, it did not have a significant effect on the composite end point of death from any cause, lifesaving cardiovascular intervention, or unplanned hospitalization for worsening heart failure. There was no beneficial effect of adaptive servo-ventilation on a broad spectrum of functional measures, including quality-of-life measures, 6-minute walk distance, or symptoms. In fact, there was a significant increase in both cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality in the adaptive servo-ventilation group. The signal for the primary end point was stronger in patients with a higher proportion of Cheyne–Stokes respiration than in those who had a lower proportion, and the signal for cardiovascular death was stronger in patients with very low left ventricular ejection fraction than in those with a higher left ventricular ejection fraction.

The findings of this study contrast with evidence from smaller studies and meta-analyses that have shown improvements in surrogate markers, including the plasma concentration of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), left ventricular ejection fraction, quality-of-life scores, functional outcomes, and mortality among patients who have heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and have central sleep apnea that is treated with adaptive servo-ventilation.11,14–17 The recently published results of the Study of the Effects of Adaptive Servo-ventilation Therapy on Cardiac Function and Remodeling in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure (SAVIOR-C) showed a lack of effect of adaptive servo-ventilation therapy on left ventricular ejection fraction and plasma BNP concentrations up to a maximum of 24 weeks.18 However, improvements in quality of life and clinical status were associated with adaptive servo-ventilation therapy in that trial — findings that were not confirmed by our study.

The CANPAP trial was a large, randomized, outcome study that investigated CPAP treatment for central sleep apnea in patients with heart failure.9 That trial showed no benefit of CPAP. A post hoc analysis of data from that trial indicated that mortality might be lower when CPAP therapy is associated with an early and significant reduction in AHI (to <15 events per hour at 3 months).10 However, in our trial, adaptive servo-ventilation showed no benefit with respect to cardiovascular end points, despite effective control of sleep-disordered breathing.

The early and sustained increase in cardiovascular mortality seen in the adaptive servo-ventilation group in this trial was unexpected, and the pathophysiological features of this effect remain to be elucidated. One possible explanation is that central sleep apnea may be a compensatory mechanism in patients with heart failure, as has been suggested previously.19 Potentially beneficial consequences of central sleep apnea, particularly Cheyne–Stokes respiration, in patients with heart failure that could have been attenuated by adaptive servo-ventilation include the resting of respiratory muscles, attenuation of excessive sympathetic nervous system activity, avoidance of hypercapnic acidosis, hyperventilation-related increases in end-expiratory lung volume, and intrinsic positive airway pressure.19 Diminishing this compensatory adaptive respiratory pattern with adaptive servo-ventilation may be detrimental in patients with heart failure, as suggested by the subgroup analysis that showed a positive association between the proportion of Cheyne–Stokes respiration and the adverse effect of adaptive servo-ventilation on cardiovascular mortality.

Another possible explanation is that the application of positive airway pressure may impair cardiac function in at least some patients with heart failure. A number of studies have documented decreased cardiac output and stroke volume during positive airway pressure therapy, particularly when the pulmonary-capillary wedge pressure is low.20–23 However, the hemodynamic effects of positive airway pressure appear to be neutral or beneficial in patients with heart failure and high wedge pressures.20–22,24 Even in patients with severe systolic dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction, ≤35%), short-term treatment with bilevel positive airway pressure therapy has been shown to significantly improve left ventricular performance.25 Furthermore, no safety concerns have been identified during the short-term application of positive airway pressure in patients with decompensated heart failure.26

Our study has a few limitations. The main limitation of the study was its unblinded design, which has the potential to introduce bias. However, this bias would be more likely to favor the active treatment group, particularly with regard to quality of life, and improvement in this outcome was not seen in the study results. In addition, owing to the epidemiologic factors associated with central sleep apnea and with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, relatively few women were recruited to the study. Finally, the study was conducted in patients who had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and therefore the results cannot be generalized to patients who have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. The study results also cannot be extrapolated to patients with predominantly obstructive sleep apnea. As compared with central apnea events, obstructive apnea events may lead to more adverse loading of the heart by increasing the left ventricular afterload by means of the combined effects of elevations in systemic blood pressure and the generation of increased negative intrathoracic pressure, which can be reversed by means of positive airway pressure therapies.

It should be noted that the algorithms used by different adaptive servo-ventilation devices vary, but the principle of treatment is the same (i.e., back-up rate ventilation with adaptive pressure support). Although previous studies have not differentiated between devices in terms of the effects of adaptive servo-ventilation therapy, there is an ongoing study of this question (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01128816) that may help determine whether the safety signal identified in SERVE-HF is limited to a particular device or algorithm.

In conclusion, we found that in patients who had heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction and predominantly central sleep apnea, the addition of adaptive servo-ventilation to guideline-based medical treatment did not improve the outcome. The risk of cardiovascular death was increased by 34%, which was sustained throughout the trial, and there was no beneficial effect on quality of life or symptoms of heart failure. These results were seen despite effective control of central sleep apnea during adaptive servo-ventilation therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funded by ResMed and others; SERVE-HF ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00733343.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Supported by ResMed and by grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit (to Dr. Cowie), the NIHR Respiratory Biomedical Research Unit (to Dr. Simonds), and the National Institutes of Health (R01HL065176, to Dr Somers).

Dr. Cowie reports receiving consulting fees from Servier, Novartis, Pfizer, St. Jude Medical, Boston Scientific, Respicardia, and Medtronic and grant support through his institution from Bayer; Dr. Woehrle, being an employee of ResMed; Dr. Wegscheider, receiving grant support from ResMed; Dr. Angermann, receiving fees for serving on advisory boards from ResMed, Servier, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Vifor Pharma, fees for serving on a steering committee from ResMed, lecture fees from Servier and Vifor Pharma, grant support from ResMed, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lundbeck, and Vifor Pharma, financial support for statistical analyses from Thermo Fisher Scientific, and study medication from Lundbeck; Dr. d’Ortho, receiving fees for serving on advisory boards from ResMed and IP Santé, lecture fees from ResMed, Philips, IP Santé, and VitalAire, grant support from Fisher and Paykel Healthcare, ResMed, Philips, ADEP Assistance, and IP Santé, and small material donations from VitalAire; Dr. Somers, receiving consulting fees from PricewaterhouseCoopers, Sorin, GlaxoSmithKline, Respicardia, uHealth, Ronda Grey, and ResMed, working with Mayo Medical Ventures on intellectual property related to sleep and cardiovascular disease, and having a pending patent (12/680073) related to biomarkers of sleep apnea; Dr. Zannad, receiving fees for serving on steering committees from Janssen Pharmaceutica, Bayer, Pfizer, Novartis, Boston Scientific, ResMed, and Takeda Pharmaceutical, receiving consulting fees from Servier, Stealth Peptides, Amgen, and CVRx, and receiving lecture fees from Mitsubishi; and Dr. Teschler, receiving consulting fees, grant support, and hardware and software for the development of devices from ResMed.

We thank the team from the Clinical Research Institute, Munich, Germany, for overseeing the trial; Nicola Ryan, B.Sc., independent medical writer, for medical writing support; and Anika Buchholz, Ph.D., Christine Eulenburg, Ph.D., Anna Suling, Ph.D., Susanne Lezius, M.Sc., and Eik Vettorazzi, M.Sc., of the Department of Medical Biometry and Epidemiology, University Medical Center Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany, for statistical calculations.

Footnotes

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oldenburg O, Lamp B, Faber L, Teschler H, Horstkotte D, Töpfer V. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with symptomatic heart failure: a contemporary study of prevalence in and characteristics of 700 patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lévy P, Pépin J-L, Tamisier R, Neuder Y, Baguet J-P, Javaheri S. Prevalence and impact of central sleep apnea in heart failure. Sleep Med Clin. 2007;2:615–621. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oldenburg O, Bitter T, Wiemer M, Langer C, Horstkotte D, Piper C. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and pulmonary arterial pressure in heart failure patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Med. 2009;10:726–730. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitter T, Westerheide N, Prinz C, et al. Cheyne-Stokes respiration and obstructive sleep apnoea are independent risk factors for malignant ventricular arrhythmias requiring appropriate cardioverter-defibrillator therapies in patients with congestive heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:61–74. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasai T, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: a bidirectional relationship. Circulation. 2012;126:1495–1510. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.070813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:686–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Javaheri S, Shukla R, Zeigler H, Wexler L. Central sleep apnea, right ventricular dysfunction, and low diastolic blood pressure are predictors of mortality in systolic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2028–2034. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yumino D, Wang H, Floras JS, et al. Relationship between sleep apnoea and mortality in patients with ischaemic heart failure. Heart. 2009;95:819–824. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.160952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley TD, Logan AG, Kimoff RJ, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure for central sleep apnea and heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2025–2033. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arzt M, Floras JS, Logan AG, et al. Suppression of central sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure and transplant-free survival in heart failure: a post hoc analysis of the Canadian Continuous Positive Airway Pressure for Patients with Central Sleep Apnea and Heart Failure Trial (CANPAP) Circulation. 2007;115:3173–3180. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma BK, Bakker JP, McSharry DG, Desai AS, Javaheri S, Malhotra A. Adaptive servoventilation for treatment of sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2012;142:1211–1221. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teschler H, Döhring J, Wang YM, Berthon-Jones M. Adaptive pressure support servo-ventilation: a novel treatment for Cheyne-Stokes respiration in heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:614–619. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.9908114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, et al. Rationale and design of the SERVE-HF study: treatment of sleep-disordered breathing with predominant central sleep apnoea with adaptive servo-ventilation in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:937–943. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hastings PC, Vazir A, Meadows GE, et al. Adaptive servo-ventilation in heart failure patients with sleep apnea: a real world study. Int J Cardiol. 2010;139:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura S, Asai K, Kubota Y, et al. Impact of sleep-disordered breathing and efficacy of positive airway pressure on mortality in patients with chronic heart failure and sleep-disordered breathing: a meta-analysis. Clin Res Cardiol. 2015;104:208–216. doi: 10.1007/s00392-014-0774-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oldenburg O, Schmidt A, Lamp B, et al. Adaptive servoventilation improves cardiac function in patients with chronic heart failure and Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takama N, Kurabayashi M. Effect of adaptive servo-ventilation on 1-year prognosis in heart failure patients. Circ J. 2012;76:661–667. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Momomura S, Seino Y, Kihara Y, et al. Adaptive servo-ventilation therapy for patients with chronic heart failure in a confirmatory, multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Circ J. 2015;79:981–990. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naughton MT. Cheyne-Stokes respiration: friend or foe? Thorax. 2012;67:357–360. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley TD, Holloway RM, McLaughlin PR, Ross BL, Walters J, Liu PP. Cardiac output response to continuous positive airway pressure in congestive heart failure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:377–382. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.2_Pt_1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Hoyos A, Liu PP, Benard DC, Bradley TD. Haemodynamic effects of continuous positive airway pressure in humans with normal and impaired left ventricular function. Clin Sci (Lond) 1995;88:173–178. doi: 10.1042/cs0880173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grace MP, Greenbaum DM. Cardiac performance in response to PEEP in patients with cardiac dysfunction. Crit Care Med. 1982;10:358–360. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Philip-Joët FF, Paganelli FF, Dutau HL, Saadjian AY. Hemodynamic effects of bilevel nasal positive airway pressure ventilation in patients with heart failure. Respiration. 1999;66:136–143. doi: 10.1159/000029355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenique F, Habis M, Lofaso F, Dubois-Randé JL, Harf A, Brochard L. Ventilatory and hemodynamic effects of continuous positive airway pressure in left heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:500–505. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Acosta B, DiBenedetto R, Rahimi A, et al. Hemodynamic effects of noninvasive bilevel positive airway pressure on patients with chronic congestive heart failure with systolic dysfunction. Chest. 2000;118:1004–1009. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.4.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray AJ, Goodacre S, Newby DE, et al. A multicentre randomised controlled trial of the use of continuous positive airway pressure and non-invasive positive pressure ventilation in the early treatment of patients presenting to the emergency department with severe acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema: the 3CPO trial. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:1–106. doi: 10.3310/hta13330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.