Abstract

Administering local anesthetics (LAs) peri- and post-operatively aims to prevent or mitigate pain in surgical procedures and after tissue injury in cases of osteoarthritis (OA) and other degenerative diseases. Innovative tissue protective and reparative therapeutic interventions such as mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are likely to be exposed to co-administered drugs such as LAs. Therefore, it is important to determine how this exposure affects the therapeutic functions of MSCs and other cells in their target microenvironment. In these studies, we measured the effect of LAs, lidocaine and bupivacaine, on macrophage viability and pro-inflammatory secretion. We also examined their effect on modulation of the macrophage pro-inflammatory phenotype in an in vitro co-culture system with MSCs, by quantifying macrophage tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α secretion and MSC prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production. Our studies indicate that both LAs directly attenuated macrophage TNF-α secretion, without significantly affecting viability, in a concentration- and potency-dependent manner. LA-mediated attenuation of macrophage TNF-α was sustained in co-culture with MSCs, but MSCs did not further enhance this anti-inflammatory effect. Concentration- and potency-dependent reductions in macrophage TNF-α were concurrent with decreased PGE2 levels in the co-cultures further indicating MSC-independent macrophage attenuation. MSC functional recovery from LA exposure was assessed by pre-treating MSCs with LAs prior to co-culture with macrophages. Both MSC attenuation of TNF-α and PGE2 secretion were impaired by pre-exposure to the more potent bupivacaine and high dose of lidocaine in a concentration-dependent manner. Therefore, LAs can affect anti-inflammatory function by both directly attenuating macrophage inflammation and MSC secretion and possibly by altering the local microenvironment which can secondarily reduce MSC function. Furthermore, the LA effect on MSC function may persist even after LA removal.

Introduction

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) possess many tissue protective and regenerative properties, including modulation of inflammatory and immune cells and chondrogenic differentiation, which make them attractive as a cellular therapeutic to treat osteoarthritis (OA).1-6 We and others have demonstrated that MSCs respond to their microenvironment and play an important role in promoting tissue regeneration in part by attenuating pro-inflammatory macrophage secretion of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α via production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2).7 Progression of OA occurs in conjunction with an increase in pro-inflammatory (M1) macrophages which not only exacerbate articular damage, but also reduce the chondrogenic potential of implanted MSCs.4, 8

Local anesthetics (LAs) are commonly used to reduce incisional pain associated with a number of surgical procedures including intra-articular surgery and may be used in conjunction with MSC implantation.1-3, 9-12 While the main therapeutic targets of LAs are voltage-gated sodium channels in neuronal cells, there is potential for them to have off-target effects on other cells in the microenvironment, including MSCs and macrophages. Several studies have demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects to LAs. These include reduced interleukin (IL)-1 secretion from mononuclear cells, concentration-dependent inhibition of macrophage phagocytosis and oxidative metabolism, reduced leukocyte adhesion,13, 14 and decreased IL-1 and IL-8 secretion from epithelial cells in conjunction with increased levels of anti-inflammatory IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) secretion.15 In fact, LAs have been used to treat inflammation associated with burn injuries, arthritis, and other pathologies with fewer side effects than traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroids.13 Given the fact that perioperative states are often associated with overactive inflammatory responses, regulating inflammation is particularly important.14, 16 However, LAs may also exhibit cytotoxicity17 and the effect of LAs on both macrophage pro-inflammatory function and MSC attenuation of this behavior has not been extensively explored.

We have previously described the in vitro effect of a panel of LAs on the secretome of quiescent and pro-inflammatory cytokine activated MSCs which indicated activation state- and anesthetic-specific changes, including decreased constitutive PGE2 secretion by high concentrations of bupivacaine.18 Using a previously established macrophage/MSC co-culture assay for MSC anti-inflammatory function,7 the current studies were designed to assess the in vitro effects of two commonly used lower or higher potency LAs, lidocaine and bupivacaine respectively, on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-activated M1 macrophages and MSC attenuation of inflammation. Our results indicate that LA can inhibit MSC anti-inflammatory function either directly or by modulating the inflammatory microenvironment, and in concert reduce MSC efficacy even after LA withdrawal. These studies suggest that effect of LA administration must be considered when developing MSC therapeutic protocols.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

Lidocaine, bupivacaine, and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Oakville, Ontario, Canada), unless otherwise stated. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). All cell culture reagents were purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA), unless otherwise stated. For comparative purposes, LA and LPS concentrations were selected based on previous in vitro studies performed by our group and others.6, 7, 15, 18-23.

Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Culture

Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) were purchased from the Institute for Regenerative Medicine (Texas A&M College of Medicine, Temple, TX). Cryopreserved MSCs were thawed at passage 2, plated as a monolayer at 3×105 cells per 175 cm2 flask, and cultured in a humidified 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. They were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium α containing no ribo- or deoxyribonucleosides, and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologics, Flowery Branch, GA), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cells were grown to 70% confluence, detached with trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and further cultured as required by experimental conditions. Only cells at low passages (3-4) were used.

Monocyte Isolation and Macrophage Differentiation

Primary mononuclear cells were isolated from peripheral blood from three human donors (The Blood Center of New Jersey, East Orange, NJ) and differentiated into macrophages as described previously.7 Briefly, blood fractions were separated by centrifugation over a Ficoll gradient of 1.077 g/mL (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The buffy coat fraction was collected and enriched for CD14+ mononuclear cells using anti-CD14 coated magnetic microbeads, according the manufacturer’s instructions (MACS, Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA). These isolated cells were seeded into 175 cm2 flasks at 107 cells/flask in supplemented Advanced RPMI 1640 medium and incubated in a humidified 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. Unattached cells were removed by aspiration after 2-6 hours and the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 5 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Differentiated M1 macrophages were collected using trypsin-EDTA after 7 days and cryopreserved in Advanced RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) until thawing for experimental use.

Assessment of Macrophage Viability

Macrophages at passage 1 were thawed, washed in Advanced RPMI 1640 , seeded into 96-well plates at 1×104 cells/well (31250 cells/cm2), and allowed to attach overnight. Cell culture medium was replaced with fully supplemented RPMI 1640 containing 0, 0.5, or 1 mM of lidocaine or bupivacaine, with or without 1 μg/mL LPSand incubated for 1, 6, or 24 hours at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Viability was assessed using an alamar blue assay, as described previously.18 Briefly, after culture in the presence of the local anesthetics, the culture supernatants were gently collected, stored at −80°C, and replaced with fresh medium containing alamar blue reagent (alamarBlue, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The fluorescence of the wells was read after 4 hours of incubation using a microplate reader (DTX 880 Multimode Detector, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). In parallel, macrophages from the same donor were seeded into 96-well plates at 1×103, 2×103, 4×103, 8×103, 1×104, and 2×104 cells/well, and allowed to attach overnight. The alamar blue assay was used to create a standard curve of fluorescence versus cell number to enable calculation of cell numbers in the experimental conditions.

MSC/Macrophage Co-Culture

Macrophages at passage 1 were thawed, washed in Advanced RPMI 1640, seeded into 24-well plates at 5×104 cells/well (2.5×104 cells/cm2), and allowed to attach overnight. Cell culture medium was replaced with fully supplemented RPMI 1640 medium containing 0, 0.5, or 1 mM of lidocaine or bupivacaine, with or without LPS (1 μg/mL). Transwell inserts (Corning, Maine, USA) were added to macrophage wells containing LPS; 5×104 MSCs in medium containing LPS (1 μg/mL) and 0, 0.5, or 1 mM of lidocaine or bupivacaine were added to the transwells. After 24 hours, culture supernatants were then gently collected, and stored at −80°C.

LA Pre-Treated MSC/Macrophage Co-Culture

Macrophages at passage 1 were thawed, washed in Advanced RPMI 1640, seeded into 24-well plates at 5×104 cells/well (2.5×104 cells/cm2), and allowed to attach overnight. Cell culture medium was replaced with fully supplemented RPMI 1640 medium with or without LPS (1 μg/mL). MSCs were seeded into 150 mm diameter, non-tissue culture treated petri dishes in fully supplemented RPMI 1640 medium containing 0, 0.5, or 1 mM lidocaine or bupivacaine and incubated at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator for 6 hours on a rocker at 2 rpm to prevent cell attachment. The cells were then collected, washed with fresh medium, and resuspended at 5×105 viable cells/mL in medium containing LPS (1 μg/mL). Transwell inserts were added to macrophage wells containing LPS; 5×104 pre-treated MSCs were added to the transwells and the co-culture was incubated for 24 hours at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator, after which the culture supernatants were then gently collected, stored at −80°C.

Cytokine Measurement

The cell culture supernatants collected from macrophages and macrophage/MSC co-cultures were analyzed using enzyme linked immunosorbent assays for TNF-α (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) and PGE2 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cytokine levels quantified in supernatants collected from macrophages alone were normalized to cell number.

Statistical Analysis

Data points represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for the indicated number of biological replicates (n), with 2-6 technical replicates/biological replicate. Viability and levels of secreted factors were normalized to their respective controls, as indicated. Statistical differences between the data were determined using Student’s t test performed in KaleidaGraph software version 4.1 (Synergy Software, Reading, PA); p values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Achieved power was determined in G*Power software version 3.1.9.224; power (1-β) values greater than 0.80 were considered statistically powerful.

Results

Macrophage viability in the presence of LAs

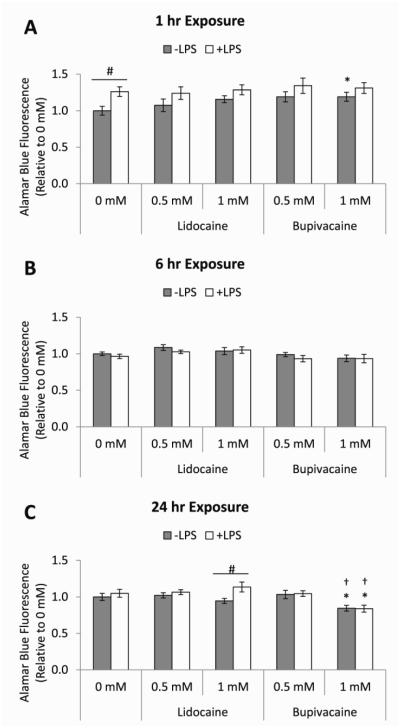

Our previous studies indicated that MSCs directly control macrophage M1 attenuation, largely via PGE2 secretion,7 and that MSC PGE2 secretion was effected by LA exposure. The current studies were designed to assess the effect of LA treatment on downstream anti-inflammatory modulation of M1 macrophages. Prior to examining LA-mediated effects on MSC modulation of macrophage function, the direct effects of LAs on quiescent and LPS-activated macrophage viability were determined by alamar blue reduction after 1, 6, or 24 hours of exposure to 0.5 mM or 1 mM lidocaine or bupivacaine (Figure 1A-C). In general, lidocaine and bupivacaine did not decrease the viability of either quiescent or LPS-activated macrophages. The higher concentration of bupivacaine, however, slightly decreased macrophage viability after 24 hours of exposure both with and without LPS activation (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Effects of LAs on macrophage viability.

The bar heights represent the relative fluorescence intensities of reduced alamar blue reagent at 4 hours of incubation on unstimulated (−LPS, grey bars) or LPS-stimulated (+LPS, white bars) macrophages treated for (A) 1, (B) 6, or (C) 24 hours with medium (0 mM) or medium containing 0.5 or 1 mM of lidocaine or bupivacaine. The data are the mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates, relative to 0 mM/−LPS. *Statistically significant difference compared to the basal medium control (0 mM). †Statistically significant difference compared 0.5 mM. #Statistically significant difference between corresponding −LPS and +LPS conditions.

Effect of LAs on macrophage TNF-α secretion

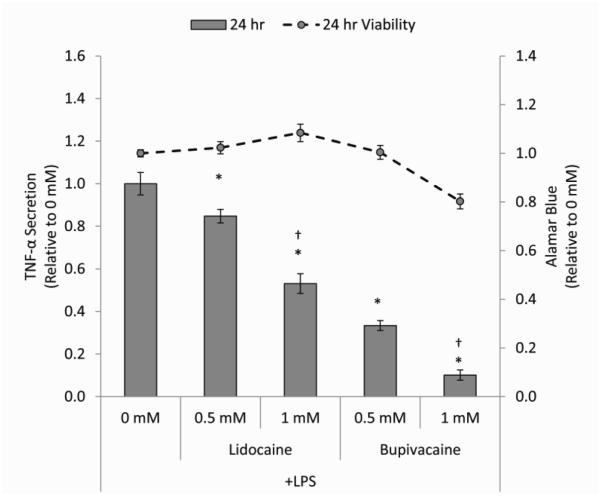

In order to quantify the effect of these LAs on macrophage M1 function, TNF-α secretion was measured after 24 hours of exposure to 0.5 mM or 1 mM lidocaine or bupivacaine. Concentration- and potency-dependent decreases in TNF-α were observed (Figure 2). LPS-activated macrophages cultured with lidocaine secreted less TNF-α than cells in basal medium in a concentration-dependent manner. Exposure to bupivacaine, the more potent LA, resulted in further concentration-dependent decreases in TNF-α secretion. Decreased TNF-a secretion from macrophages was not correlated with decreased viability, except at the higher concentration of bupivacaine. These effects were consistent across the panel of 3 macrophage donors used, although baseline levels of secretion varied (Table 1). To further confirm the significance of this effects across the 3 macrophage donor panel, a post hoc analysis to compute the achieved power was performed, obtaining statistical powers (1-β) greater than 0.90.

Figure 2. Effects of LAs on macrophage TNF-α secretion.

The bar heights represent the level of TNF-α (relative to 0 mM) secreted from LPS-stimulated macrophages treated for 24 hours with medium (0 mM) or medium containing 0.5 or 1 mM of lidocaine or bupivacaine. Data points on the overlaid line graph (grey circles, broken line) are alamar blue fluorescence values (relative to 0 mM) associated with the corresponding 24 hour time point. The data are the mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. *Statistically significant difference compared to the basal medium control (0 mM). †Statistically significant difference compared 0.5 mM.

Table 1.

TNF-α secretion of macrophages isolated from different donors and treated with LPS and LAs for 24 hours.

| Lidocaine/LPS |

Bupivacaine/LPS |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − LPS | + LPS | 0.5 mM | 1.0 mM | 0.5 mM | 1.0 mM | ||

|

TNF-α

(pg/mL/104cells) |

Donor 1 | 0.298 | 111.2 | 92.47 | 42.70 | 45.76 | 21.63 |

| Donor 2 | 0.812 | 418.0 | 335.6 | 244.0 | 113.1 | 19.05 | |

| Donor 3 | 1.316 | 541.2 | 491.7 | 349.7 | 171.4 | 33.28 | |

The data are the mean of n = 3 technical replicates per biological replicate (donor).

Effect of LAs on macrophage and MSC co-culture

Therapeutic MSCs implanted into an inflammatory environment are likely to be exposed to concurrently administered LAs. Therefore, to assess the effect of LAs on the MSC-mediated modulation of macrophage inflammation, we co-cultured both cell types in the presence of LPS with and without 0.5 or 1 mM lidocaine or bupivacaine for 24 hours. In the absence of MSCs, lidocaine and bupivacaine reduced TNF-α secretion from LPS-stimulated macrophages in a concentration-dependent manner, with bupivacaine more potently exhibiting this effect, consistent with the results described above (Figure 3). As expected, MSCs were able to attenuate macrophage TNF-α secretion in the absence of LAs. While the concentration-dependent reduction of macrophage TNF-α secretion in the presence of 1 mM lidocaine and both concentrations of bupivacaine was sustained when MSCs were introduced into the culture, there was no further attenuation observed. The presence of MSCs further enhanced TNF-α suppression only when combined with 0.5 mM lidocaine. These effects were consistent across the panel of 3 macrophage donors used, although baseline levels of secretion varied (Table 2).

Figure 3. MSC modulation of macrophage secretion in the presence of LAs.

The bar heights represent the level of TNF-α secreted from LPS-stimulated macrophages co-cultured for 24 hours with (white bars) or without (grey bars) MSCs in LPS-supplemented medium (0 mM) or LPS-supplemented medium containing 0.5 or 1 mM of lidocaine or bupivacaine. Values are presented as cytokine level relative to the LPS control without MSCs (0 mM, − MSCs). The data are the mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. *Statistically significant difference compared to the LPS control (0 mM, −MSCs). #Statistically significant difference compared to the −MSC controls. †Statistically significant difference compared to 0.5 mM. ΔStatistically significant difference compared to no anesthetic MSC control (0 mM, +MSCs).

Table 2.

TNF-α secretion of macrophages isolated from different donors and co-cultured for 24 hours with MSCs in the presence of LAs.

| Lidocaine/LPS |

Bupivacaine/LPS |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − LPS | + LPS | 0.5 mM | 1.0 mM | 0.5 mM | 1.0 mM | |||

|

TNF-α

(pg/mL) |

−

MSC |

Donor 1 | 2.15 | 124.7 | 107.2 | 65.65 | 22.39 | 1.047 |

| Donor 2 | 0 | 1100 | 1220 | 716.8 | 452.5 | 17.88 | ||

| Donor 3 | 0 | 404.1 | 443.0 | 260.9 | 167.0 | 57.71 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| + MSC |

Donor 1 | - | 108.9 | 97.99 | 64.78 | 18.51 | 0.873 | |

| Donor 2 | - | 1074 | 778.0 | 597.5 | 328.0 | 20.16 | ||

| Donor 3 | - | 345.5 | 315.1 | 192.2 | 138.3 | 47.86 | ||

The data are the mean of n = 2-6 technical replicates per biological replicate (donor).

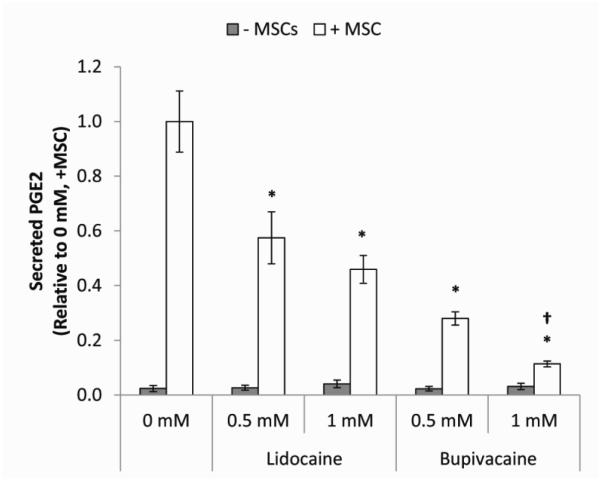

Our previous experimental studies indicated that PGE2 secretion from MSC was largely responsible for their effect on M1 macrophage attenuation.7 In addition, we previously observed that a high concentration (1 mM) of lidocaine or bupivacaine resulted in decreased constitutive secretion of PGE2 by monolayer MSCs.18 Therefore, we next characterized the effect of LAs on PGE2 levels in the co-culture of macrophages and MSCs. Levels of PGE2 detected from macrophages alone with and without LAs were low relative to co-cultures of macrophages and MSCs, suggesting that the MSCs were the main source of PGE2 (Table 3). As seen for TNF-α, PGE2 levels were attenuated in the presence of LAs in a potency- and concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4). Therefore, reductions in TNF-α did not appear to be mediated by secretion of PGE2.

Table 3.

Secreted PGE2 levels in supernatants of 24 hour co-cultures of MSCs and macrophages isolated from different donors in the presence of LAs.

| Lidocaine/LPS |

Bupivacaine/LPS |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − LPS | + LPS | 0.5 mM | 1.0 mM | 0.5 mM | 1.0 mM | |||

|

PGE2

(pg/mL) |

− MSC |

Donor 1 | 0 | 2.411 | 9.54 | 29.35 | 10.03 | 25.11 |

| Donor 2 | 19.69 | 56.06 | 48.79 | 61.52 | 43.74 | 43.76 | ||

| Donor 3 | 10.87 | 16.57 | 39.41 | 20.95 | 12.69 | 16.94 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| + MSC |

Donor 1 | - | 1352 | 782.8 | 612.4 | 365.6 | 126.7 | |

| Donor 2 | - | 769.8 | 561.1 | 541.7 | 311.5 | 83.06 | ||

| Donor 3 | - | 3240 | 1584 | 1029 | 717.5 | 499.4 | ||

The data are the mean of n = 2-6 technical replicates per biological replicate (donor).

Figure 4. Secreted PGE2 levels in MSC/macrophage co-culture supernatants.

The bar heights represent the level of secreted PGE2 present after co-culture of macrophages with MSCs for 24 hours in LPS-supplemented medium (0 mM) or LPS-supplemented medium containing 0.5 or 1 mM of lidocaine or bupivacaine. Values are presented as cytokine level relative to the LPS control (0 mM). The data are the mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. *Statistically significant difference compared to 0 mM. †Statistically significant difference compared to 0.5 mM.

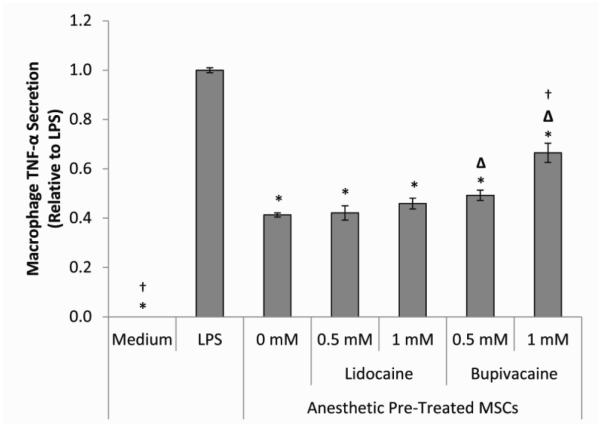

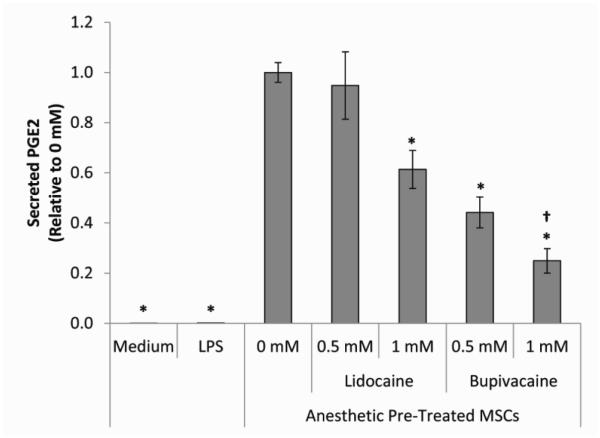

To further tease out the effect of LAs on the MSC-mediated modulation of macrophages, MSCs were cultured without or with 0.5 mM or 1 mM lidocaine or bupivacaine for 6 hours and then co-cultured with LPS-stimulated macrophages for 24 hours. MSCs that were not pre-treated with LAs significantly decreased macrophage TNF-α secretion (Figure 5). While pre-exposure to lidocaine did not appear to have a major effect on the ability of MSCs to attenuate macrophage TNF-α secretion, bupivacaine significantly inhibited this function in a concentration-dependent manner. PGE2 in these co-cultures was elevated compared to no MSCs. Pre-treatment of the MSCs with the lower concentration of lidocaine did not result in a significant change in the PGE2 level. PGE2 was decreased, however, in a concentration- and potency-dependent manner for MSCs pre-treated with bupivacaine or the higher concentration of lidocaine.

Figure 5. Effects of LA pre-treatment on MSC modulation of macrophage secretion.

The bar heights represent the level of TNF-α secreted from LPS-stimulated macrophages co-cultured for 24 hours with MSCs pre-treated for 6 hours with medium (0 mM) or medium containing 0.5 or 1 mM of lidocaine or bupivacaine. Values are presented as cytokine level relative to the LPS control (0 mM). The data are the mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. *Statistically significant difference compared to LPS-stimulated control. ΔStatistically significant difference compared to medium (0 mM) pre-treated MSC control. †Statistically significant difference compared to 0.5 mM.

Discussion

MSC have been used to control inflammation and as a replacement cell source in a number of surgical procedures and tissue injuries including those related to OA.25 In our previous studies, we found that MSCs can attenuate pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotypes and play a central therapeutic role in spinal cord injury inflammation resolution largely via secretion of a number of important factors including PGE2.5, 7 In order to optimize MSC anti-inflammatory therapy, the off-target effects of the LAs that may be present in the MSC microenvironment must also be considered, since MSCs respond to their local milieu and regulate their secretome in response to it. Therefore, the goal of our studies was to determine the effect of the LAs lidocaine and bupivacaine on MSC anti-inflammatory modulation of macrophages. Our results indicate that while LAs have a direct effect on attenuating macrophage inflammation, MSC do not significantly reduce macrophage inflammation in the presence of LAs, potentially due to both direct action on the macrophages and MSCs and reduction of activating signals in the microenvironment. The implications of these results may be important to consider in designing therapeutic MSC intervention protocols.

Tissue trauma and tissue degenerative diseases such as OA often require surgical intervention to reduce injury and to introduce therapeutic medical devices, tissue constructs or pharmacological treatments. However, these procedures also activate inflammatory cellular cascades in which macrophages play a major role and which under normal conditions assist in reducing infection and initiating tissue repair.13, 16, 26 Injury severity, which can be exacerbated by surgical incisions, further amplifies tissue inflammation sometimes leading to increased pain and patient morbidity.13, 17, 27, 28 While administration of LAs controls procedural pain by targeting voltage-gated sodium channels on neuronal cells, these molecules have the potential for off target effects such as cytotoxicity. Additionally, pain associated with the peri-operative state is associated with increased levels of inflammation, which are often difficult to resolve.25 Anti-inflammatory treatment can assist in post-operative recovery, but non-specific anti-inflammatories such as NSAIDs and corticosteroids, often increase the risk of secondary infection and do not prevent progression of tissue degeneration.13 Therefore, a growing surgical goal is to reduce inflammation without compromising immunity. While anti-inflammatory MSC implantation may resolve some of these issues, the effect of anesthetic administration on MSC function must be considered when developing implantation protocols.

Complementing our previous work examining the effect of LAs on MSCs alone, we designed studies to evaluate the in vitro effect of the LAs on macrophages isolated from three different donors, prior to examining their effect on MSC-macrophage interaction. We observed that, with the exception of longest exposure to bupivacaine at the highest concentration used, LAs did not adversely affect macrophage viability in the presence or absence of LPS and thus viability changes could not account for decreases in TNF-α secretion. However, significant effects of the LAs were seen on macrophage secretion of TNF-α in response to LPS activation as macrophage secretion of TNF-α was attenuated in a concentration- and LA potency-dependent manner. Other studies have previously described anti-inflammatory LA function. For example, Lahav et al. described the effect of lidocaine on epithelial cells, which included inhibition of inflammatory IL-1β secretion and promotion of anti-inflammatory IL-1RA secretion. 15 Others have described reduced IL-1 secretion from mononuclear cells, concentration-dependent inhibition of macrophage phagocytosis and oxidative metabolism, and reduced leukocyte adhesion.13, 14 It has been hypothesized that this was due to a suppression of endotoxin or cytokine stimulation of the inflammatory system by interfering with G-protein-coupled receptor signaling.17 Therefore, in our in vitro system, the M1 activation of the macrophages by LPS may have been actively inhibited by the LAs.

Given that regenerative and anti-inflammatory MSCs are likely to be implanted into an already inflamed environment, we evaluated the effect of MSCs on attenuating TNF-α secretion from co-cultured LPS-activated macrophages in the presence of LAs. We observed that while MSCs alone were able to attenuate LPS-induced macrophage TNF-α secretion, the additional presence of MSCs with the LAs did not generally enhance reduction of TNF-α secretion compared to LAs alone, with the exception of the lowest concentration of lidocaine and in fact, in most cases the LA anti-inflammatory affect was more dramatic than MSC affects. Furthermore, when MSCs were pre-treated with bupivacaine, attenuation of TNF-α secretion was also significantly impaired. In our previous studies, we found that MSCs were differentially affected by LAs via concentration-dependent secretome changes.18 This included the reduction of MSC constitutive PGE2 secretion by both lidocaine and bupivacaine at the same high concentration (1 mM) used in the current studies, albeit following a 48 hour rather than 24 hour exposure.

We and others have identified PGE2 as a dominant MSC-secreted factor modulating macrophage phenotype.7, 29, 30 In our current studies, PGE2 in co-cultures of MSCs and macrophages was reduced in a potency- and concentration-dependent manner in the presence of LAs and when MSCs were pre-treated with LAs. There is evidence that LAs may actively inhibit parts of the prostaglandin synthesis pathway.13 Furthermore, in order to produce large amounts of PGE2 and other immunomodulatory factors, MSCs must be activated by external factors such as inflammatory cytokines.31, 32 Thus the inherent anti-inflammatory properties of the LAs resulting in reduced levels of inflammatory factors could also potentially affect the macrophage-MSC cross-talk that induces secretion of immunomodulatory factors by MSCs. In the LA pre-treated MSC experiments, macrophages were not exposed to LAs and therefore could respond equally to the bolus of LPS in all conditions, providing similar levels of pro-inflammatory factors to stimulate the MSCs. This additionally indicates action of the LAs directly on the MSCs. In the case of the lower concentration of lidocaine, while PGE2 levels were still decreased, sufficient PGE2 secretion may still have contributed to TNF-α attenuation.

Decreases in viability by LAs may also play a role in the effects seen by reducing the number of macrophages available to produce activating signals and/or the number of MSCs responding to the stimuli. However, functional macrophage changes were not coincident with LA cytotoxicity effects at the concentrations tested, except at the highest concentration of bupivacaine. Therefore based on this and previous data, where larger cytotoxic effects were observed, effects on MSC viability may contribute more than that of the macrophages.18

All of the results observed were dependent on both the LA concentration and potency, where the effects of bupivacaine were significantly more potent than lidocaine. This potency difference has been well established in vivo and was also seen in our previous studies.18, 33 These differences can be attributed to physiochemical properties of the LAs. While lidocaine has moderate lipid solubility and moderate reversible serum protein binding capacity, bupivacaine has high lipid solubility and high reversible serum protein binding, which could result in higher penetration into cells and longer bioavailability, respectively.34 In previous studies, we observed that in addition to decreased viability, the proliferative ability of MSCs to recover after exposure to bupivacaine was significantly impaired. Similarly, MSC ability to recover functionally after exposure to bupivacaine may also be impaired, as indicated by significantly decreased attenuation of macrophage TNF-α secretion and PGE2 secretion by bupivacaine pre-treated MSCs. Although the PGE2 level in these co-culture conditions was also significantly diminished at the higher concentration of lidocaine, it may have still been sufficient to achieve a level of TNF-attenuation similar to that of MSCs with no LA pre-treatment. Therefore, MSC function could continue to be affected even after degradation and metabolic clearance of the active compound. This may be particularly important given the multi-functional therapeutic MSC role in tissue repair. MSC may not only attenuate inflammation but also promote differentiation and tissue regeneration, functions which may be similarly compromised by LA exposure.

Compared to therapeutic concentrations commonly used in orthopedic practice 2, we have utilized relatively low LA concentrations in these studies that are consistent with the in vitro studies performed by others. 15, 19, 35, 36 When administered intra-articulary, LA volumes can range from 12.5% to 50% of the total synovial capsule’s capacity, resulting in concentrations of 4-17 mM for lidocaine from a 1% (10 mg/mL) stock solution and 2-7 mM for bupivacaine from a 0.5% (5 mg/mL) stock solution. 2, 37 Although the concentrations used in this study are lower than clinically relevant concentrations, it is clear from our studies that exposure of macrophages and MSCs to anesthetics has a significant effect on their secretion and immunomodulatory function respectively. The experimental designs also tested lidocaine and bupivacaine at equimolar rather than equipotent concentrations. While this is appropriate and common in in vitro studies, comparisons of these two LAs in in vivo and clinical models should be done by selecting equipotent doses in future studies. Similar dose-dependent trends in effects of amide LAs on MSCs have been observed, however, when using clinically relevant concentrations in vitro. 2

Our studies indicate that LAs can affect the viability and secretion of macrophages and MSCs directly and also the cross-talk between the two cell types potentially by altering the microenvironment which dictates the MSC response. In order to most effectively utilize MSCs to mediate inflammation and promote regenerative in applications where LAs are also used as treatments, the choice of LA may be relevant. Consequently, the assay we described here may be used to screen anesthetics for pro- or anti-inflammatory properties. While we have tested the effects of lidocaine and bupivacaine on a panel of three macrophage donors, this panel must be further expanded to study age differences and diseases, including inflammatory disorders that may also play a role in anesthesia-mediated MSC function. In addition, a broader anesthetic concentration range should be tested. Nevertheless, our studies suggest that in order to infuse MSCs in the presence of LA, carefully controlled anesthesia delivery approaches may be needed to ensure sustained pain reduction without compromising MSC function.

Figure 6. Secreted PGE2 levels in pre-treated MSC/macrophage co-culture supernatants.

The bar heights represent the level of secreted PGE2 present after 24 hour co-culture of LPS-activated macrophages with MSCs that were pre-treated for 6 hours with medium without (0 mM) or with 0.5 or 1 mM of lidocaine or bupivacaine. Values are presented as PGE2 level relative to 0 mM. The data are the mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates. *Statistically significant difference compared to 0 mM. †Statistically significant difference compared to 0.5 mM.

Highlights.

Effects local anesthetics (LAs) on MSC immunomodulation of macrophages were tested.

The presence of LAs directly attenuated M1 macrophage TNF-α secretion.

MSCs cultured with macrophages and LAs did not enhance this anti-inflammatory effect.

MSC attenuation of TNF-α and PGE2 secretion were impaired by pre-exposure to LAs.

LAs used with MSCs therapies should be carefully selected to ensure therapeutic efficacy.

Acknowledgements

Support for this work came from grants from the New Jersey Commission for Brain Injury Research (CBIR12IRG019), the National Institutes of Health (Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 GM8339 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences), and the United States Department of Education (Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need Award P200A100096).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Breu A, et al. Cytotoxicity of local anesthetics on human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(10):1676–84. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dregalla RC, et al. Amide-type local anesthetics and human mesenchymal stem cells: clinical implications for stem cell therapy. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3(3):365–74. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahnama R, et al. Cytotoxicity of local anesthetics on human mesenchymal stem cells. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2013;95(2):132–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fahy N, et al. Human osteoarthritic synovium impacts chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells via macrophage polarisation state. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2014;22(8):1167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barminko J, et al. Encapsulated mesenchymal stromal cells for in vivo transplantation. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2011;108(11):2747–58. doi: 10.1002/bit.23233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucchinetti E, et al. Antiproliferative effects of local anesthetics on mesenchymal stem cells: potential implications for tumor spreading and wound healing. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(4):841–56. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31824babfe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barminko JA, et al. Fractional factorial design to investigate stromal cell regulation of macrophage plasticity. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2014;111(11):2239–51. doi: 10.1002/bit.25282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, et al. Inhibition of fucosylation reshapes inflammatory macrophages and suppresses type II collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2368–79. doi: 10.1002/art.38711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrao J, et al. Effect of local anaesthetic infiltration with bupivacaine and ropivacaine on wound healing: a placebo-controlled study. Int Wound J. 2014;11(4):379–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farhangkhoee H, Li EY, Thoma A. Local anesthetics for skin grafting and local flaps. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2013;40(4):537–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta D, et al. A comparative evaluation of local application of the combination of eutectic mixture of local anesthetics and capsaicin for attenuation of venipuncture pain. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2013;116(3):568–71. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182788376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright KT, et al. Characterization of the cells in repair tissue following autologous chondrocyte implantation in mankind: a novel report of two cases. Regenerative medicine. 2013;8(6):699–709. doi: 10.2217/rme.13.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cassuto J, Sinclair R, Bonderovic M. Anti-inflammatory properties of local anesthetics and their present and potential clinical implications. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2006;50(3):265–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollmann MW, Durieux ME. Local anesthetics and the inflammatory response: a new therapeutic indication? Anesthesiology. 2000;93(3):858–75. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200009000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lahav M, et al. Lidocaine inhibits secretion of IL-8 and IL-1beta and stimulates secretion of IL-1 receptor antagonist by epithelial cells. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2002;127(2):226–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01747.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholson G, Hall GM. Effects of anaesthesia on the inflammatory response to injury. Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2011;24(4):370–4. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328348729e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lirk P, Picardi S, Hollmann MW. Local anaesthetics: 10 essentials. European journal of anaesthesiology. 2014;31(11):575–85. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray A, et al. Effect of Local Anesthetics on Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Secretion. Nano LIFE. 2015;5:1550001-1-13. doi: 10.1142/S1793984415500014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu J, et al. Bupivacaine induces apoptosis via mitochondria and p38 MAPK dependent pathways. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;657(1-3):51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Navasa N, et al. Regulation of oxidative stress by methylation-controlled J protein controls macrophage responses to inflammatory insults. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(1):135–45. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belge KU, et al. The proinflammatory CD14+CD16+DR++ monocytes are a major source of TNF. J Immunol. 2002;168(7):3536–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu H, et al. Scavenger receptor A (SR-A) is required for LPS-induced TLR4 mediated NF-κB activation in macrophages. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 2012;1823(7):1192–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray A, et al. Identification of IL-1β and LPS as optimal activators of monolayer and alginate-encapsulated mesenchymal stromal cell immunomodulation using design of experiments and statistical methods. Biotechnology Progress. 2015;31(4):1058–1070. doi: 10.1002/btpr.2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faul F, et al. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–91. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pers YM, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for the management of inflammation in osteoarthritis: state of the art and perspectives. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(11):2027–35. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sindrilaru A, et al. An unrestrained proinflammatory M1 macrophage population induced by iron impairs wound healing in humans and mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121(3):985–97. doi: 10.1172/JCI44490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banz VM, Jakob SM, Inderbitzin D. Review article: improving outcome after major surgery: pathophysiological considerations. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2011;112(5):1147–55. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181ed114e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang JX, Eckenhoff MF, Eckenhoff RG. Anesthetic modulation of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2011;24(4):389–94. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834871c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Blanc K, Davies LC. Mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune response. Immunol Lett. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Blanc K, Mougiakakos D. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(5):383–96. doi: 10.1038/nri3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krampera M. Mesenchymal stromal cell 'licensing': a multistep process. Leukemia. 2011;25(9):1408–14. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi Y, et al. How mesenchymal stem cells interact with tissue immune responses. Trends in Immunology. 2012;33(3):136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker DE, Reed KL. Local anesthetics: review of pharmacological considerations. Anesthesia Progress. 2012;59(2):90–101. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-59.2.90. quiz 102-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLure HA, Rubin AP. Review of local anaesthetic agents. Minerva Anestesiologica. 2005;71(3):59–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Girard AC, et al. New Insights into Lidocaine and Adrenaline Effects on Human Adipose Stem Cells. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2013;37(1):144–152. doi: 10.1007/s00266-012-9988-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malet A, et al. The Comparative Cytotoxic Effects of Different Local Anesthetics on a Human Neuroblastoma Cell Line. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2015;120(3):589–596. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lagan G, McLure HA. Review of local anaesthetic agents. Current Anaesthesia and Critical Care. 2004;15(4):247–254. [Google Scholar]