Abstract

In 1999, the American Journal of Pathology published an article, entitled “Vascular channel formation by human melanoma cells in vivo and in vitro: vasculogenic mimicry” by Maniotis and colleagues, which ignited a spirited debate for several years and earned the journal's distinction of a “citation classic” (Maniotis et al., 1999). Tumor cell vasculogenic mimicry (VM), also known as vascular mimicry, describes the plasticity of aggressive cancer cells forming de novo vascular networks and is associated with the malignant phenotype and poor clinical outcome. The tumor cells capable of VM share the commonality of a stem cell-like, transendothelial phenotype, which may be induced by hypoxia. Since its introduction as a novel paradigm for melanoma tumor perfusion, many studies have contributed new findings illuminating the underlying molecular pathways supporting VM in a variety of tumors, including carcinomas, sarcomas, glioblastomas, astrocytomas, and melanomas. Of special significance is the lack of effectiveness of angiogenesis inhibitors on tumor cell VM, suggesting a selective resistance by this phenotype to conventional therapy. Facilitating the functional plasticity of tumor cell VM are key proteins associated with vascular, stem cell, extracellular matrix, and hypoxia-related signaling pathways -- each deserving serious consideration as potential therapeutic targets and diagnostic indicators of the aggressive, metastatic phenotype. This review highlights seminal findings pertinent to VM, including the effects of a novel, small molecular compound, CVM-1118, currently under clinical development to target VM, and illuminates important molecular pathways involved in the suppression of this plastic, aggressive phenotype, using melanoma as a model.

Keywords: Vascular mimicry, Tumor cell plasticity, CVM-1118, Vascular mimicry pathways, Melanoma, Transendothelial phenotype

1. Introduction

Cancer deaths predominantly result from metastases that are resistant to conventional therapies. Indeed, the strategies to treat cancer in general are confounded by the heterogeneous composition of most tumors, where conventional therapies do not target all subpopulations, especially those with stem cell properties which in many cases are drug resistant. In the war on cancer, the early seminal findings of Dr. Folkman and colleagues guided scientists and the pharmaceutical industry to focus their efforts on targeting angiogenesis as a means to disrupt tumor growth (Folkman, 1995). Although this approach of inhibiting endothelial cells forming the neovasculature of growing tumors seemed strategically sound, the resulting angiogenesis inhibitor trials have been disappointing (Steeg, 2003). However, the knowledge gained from this approach, together with genomic analyses, have advanced our understanding of heterogeneous cancer cell phenotypes, including cancer stem cells, and have led to viable combinatorial strategies based on solid molecular findings (reviewed in Kirschmann et al., 2012).

One of the new paradigms that has emerged from a combined molecular and histopathological investigation has been named “vasculogenic mimicry”, also referred to as “vascular mimicry” (VM), and describes the de novo formation of perfusable, matrix-rich, vasculogenic-like networks by aggressive tumor cells in 3-dimenstional matrices in vitro which correlated with matrix-rich networks in patients' aggressive tumors (Maniotis et al., 1999). The initial morphologic and molecular characterization of VM was made in human melanoma in which the tumor cells were shown to coexpress endothelial and tumor markers and formed channels, networks, and tubular structures that are rich in laminin, collagens IV and VI, and heparin sulfate proteoglycans, containing plasma and red blood cells, revealing a perfusion pathway for rapidly growing tumors, as well as an escape route for metastasis (Hendrix et al., 2003). Remarkably, these findings agree with very early reports by others suggesting the perfusion of melanoma tumors via nonendothelial-lined channels based on morphological findings (Warren and Shubick, 1966). Since the introduction of VM, myriad studies have contributed mechanistic insights into the induction, formation, and targeting of VM across a variety of cancers in addition to melanoma; including sarcomas (Ewing, mesothelial, synovial, osteosarcoma, alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma); carcinoma(s) of the breast, ovary, skin, lung, prostate, bladder, and kidney; and gliomas, glioblastoma, and astrocytoma (reviewed in Hendrix et al., 2003). Collectively, these studies have given us a greater appreciation for the complexity of the tumor vasculature, which can be derived from a variety of sources, including angiogenic vessels, cooption of preexisting vessels, intussusceptive microvascular growth, mosaic vessels lined by both tumor cells and endothelium, postnatal vasculogenesis, and VM (Dôme et al., 2007; Carmeliet and Jain, 2011). Furthermore, recent studies have shown the tumor origin of endothelial-like cells in specific cancers (Ricci-Vitiani et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010), further illuminating a genetically unstable and heterogeneous vasculature. Most compelling is the resistance of tumor cell VM to the majority of conventional therapies, thus emphasizing the need for new targeting approaches based on robust molecular findings (van de Schaft et al., 2004; Seftor et al., 2012; Kirschmann et al., 2012).

2. Tumor cell plasticity underlies vascular mimicry

Throughout many different cancer types, the tumor cells capable of VM exhibit a remarkable degree of plasticity, indicative of a multipotent phenotype usually associated with embryonic stem cells. The molecular signature of the VM phenotype has revealed genes associated with embryonic progenitors, endothelial cells, vessel formation, matrix remodeling, and coagulation inhibitors, and the down-regulation of genes predominantly associated with lineage specific phenotype markers (Bittner et al., 2000; Seftor et al., 2002). While the initial microarray studies revealed the differential molecular profile of highly aggressive vs. nonaggressive human melanoma cells, later studies using laser capture microdissection and microgenomics profiling of melanoma VM networks vs. endothelial-formed angiogenic vasculature confirmed the upregulated expression of key angiogenesis-related and stem cell-associated genes by the melanoma cells (Demou and Hendrix, 2008). However, unlike normal embryonic progenitors, these tumor cells lack critical regulatory checkpoints which underlie their multipotent phenotype and contribute to unregulated growth and aggressive behavior (Postovit et al., 2008). Recent studies have shed light on the induction of tumor cell plasticity pertinent to melanoma VM, by indicating that the hypoxic microenvironment contributes to the phenotype switch -- specifically allowing melanoma cells to contribute to blood vessel formation (Mihic-Probst et al., 2012). Collectively, these findings provide new insights into the molecular underpinnings of VM leading to an alternative perfusion pathway found in many aggressive tumors.

3. Functional relevance of vascular mimicry in cancer

A meta-analysis of 22 eligible clinical studies with data relevant to VM and 5-year survival of 3,062 patients across 15 cancer types revealed tumor VM is associated with poor prognosis (Cao et al., 2013). Thus, the appearance of VM in the tumors of patients with a poor clinical outcome implies a functionally relevant advantage imparted by VM pertinent to the survival of the aggressive tumor cell phenotype. While vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-dependent tumor angiogenesis plays a critical role in the initiation and promotion of tumor progression and has proven to be a viable therapeutic target for certain solid tumors, subsequent failures in this approach resulting from the development of inherent and/or acquired resistance has led to a greater understanding of VEGF-independent angiogenesis (Dey et al., 2015). Although tumor angiogenesis does not directly equate to a VEGF-dependent function, studies examining VEGF-independent angiogenesis have identified key factors, such as the role of myeloid cells and VM, that are responsible for this activity. More specifically, cell-originated neovascularization encompassing tumor-derived endothelial cell-induced angiogenesis and VM have been proposed to be involved in the development of resistance to anti-VEGF therapy seen in glioblastoma multiforme (Soda et al., 2013), and breast cancer cells have been shown to transdifferentiate to drive VM (Paulis et al., 2010). Other studies have shown that angiogenic primary breast cancer can relapse not only as angiogenic, but non-angiogenic lung metastases, which can lead to cancer progression where the tumors are likely to be resistant to anti-angiogenic treatment (Pezzella et al. 2000). Together, these observations suggest that VM may be regarded as one of the major causes of the development of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy in solid tumors (Dey et al., 2015).

Experimental landmark studies have demonstrated a physiological perfusion of blood between endothelial-lined mouse vasculature and VM networks in human tumor xenografts using Doppler imaging of circulating microbeads (Hendrix et al., 2000; Ruf et al., 2003). Additional findings from these studies elucidated the anticoagulant properties of tumor cells lining VM networks, facilitating the flow of blood in aggressive tumors. In this manner, VM can provide a functional perfusion pathway for rapidly growing tumors by transporting fluid from leaky vessels and/or connecting with endothelial-lined vasculature. Equally important is the lumenization of VM networks, which involves a Caspase-3-driven process (Vartanian et al., 2007). A noteworthy example of VM functional plasticity and the importance of hypoxia as a catalyst of this phenotype was shown by transplanting human metastatic melanoma cells into an ischemic, hypoxic mouse limb, which resulted in the formation of chimeric vasculature composed of human melanoma and mouse endothelial cells (Hendrix et al., 2002). After restoring blood flow and normoxic conditions to the limb, the melanoma cells formed a large tumor mass, which illustrated the remarkable influence of the microenvironment on the transendothelial differentiation of melanoma cells that reverted to a more tumorigenic phenotype as the environmental cues changed. The functional plasticity associated with VM and the underlying multipotent tumor cell phenotype are supported by a complex integration of signaling pathways that are typically restricted to events in embryonic development, remodeling, and neovascularization.

4. Key signaling pathways in vascular mimicry

4.1 Vascular signaling pathways

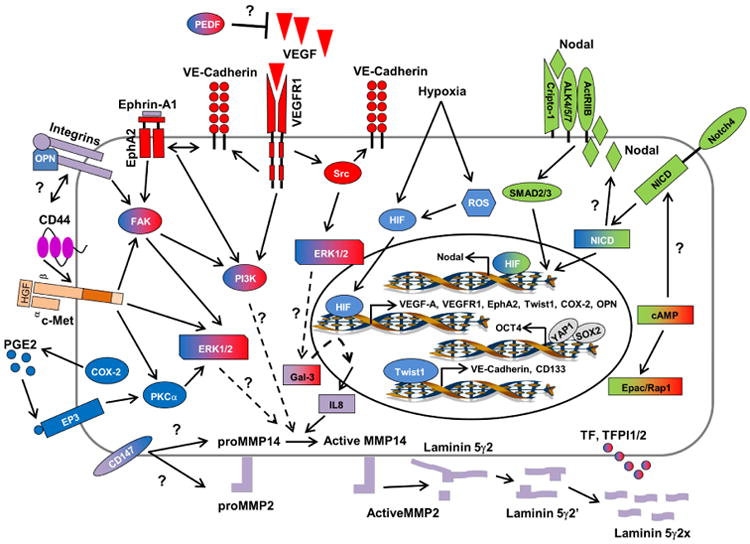

The molecular dissection of the mechanisms involved in mediating VM began with microarray analysis of highly aggressive vs. nonaggressive human melanoma cell lines. These data identified a molecular signature that revealed the complexity of the underlying signal transduction pathways (Bittner et al., 2000; Seftor et al., 2002), which are highlighted in Figure 1, and ultimately resulted in the validation of key findings in patient tumor samples. Two of the initial proteins identified to play critical roles in mediating melanoma VM, were VE-cadherin, a cell-cell adhesion molecule associated with endothelial cells, and EphA2, an epithelial cell-associated kinase involved in ephrin-A1 induced angiogenesis (Hendrix et al., 2001; Hess et al., 2001). Studies designed to test the role of these proteins in promoting melanoma VM, revealed that down-regulation of either VE-cadherin or EphA2 inhibited VM. Additional perturbation demonstrated that VE-cadherin was able to modulate the location and level of phosphorylation associated with EphA2, providing the first evidence that signal transduction from the cell surface was necessary for VM (Hess et al., 2006b). These pivotal studies prompted additional experiments addressing the importance of many cytoplasmic kinases involved in VM including phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (Hess et al., 2003; Hess et al., 2006a). Both PI3K and FAK were found to be phosphorylated downstream of EphA2 and VE-cadherin leading to increased activation of the extracellular regulatory kinase 1 and 2 (Erk1/2), the upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 14, and increased MMP-2 activity. Increased MMP-14 and MMP-2 activity promotes the cleavage of Laminin 5γ2-chain into the γ2′ and γ2× pro-migratory fragments leading to increased invasion, migration, and VM in melanoma cells, providing vascular structural integrity (Seftor et al., 2001). Although the mechanism for increased expression of VE-cadherin or EphA2 in human melanoma is not well understood, it has been demonstrated that VE-cadherin expression is increased by the transcription factor Twist 1 in hepatocellular carcinoma contributing to VM in this cell type and possibly others (Sun et al., 2010).

Fig. 1.

Schematic model of signaling pathways implicated in tumor cell vascular mimicry (VM). Only signaling molecules which have been specifically modulated using antisense oligonucletides, small inhibitory RNAs, blocking antibodies, small molecule inhibitors, or transient transfections are depicted -- demonstrating their ability to directly affect VM, and are categorized as vascular (red), embryonic/stem cell (green), tumor microenvironment (purple), and hypoxia signaling pathways (blue). Molecules shaded with two different colors demonstrate overlap between major VM signaling pathways. Involvement of Gal3 and IL-8 in VM has been previously reviewed (Mourand-Zeidan et al., 2008). Question marks indicate the potential involvement of a protein and/or downstream effector protein or proteins in modulating VM in aggressive cancer cells, for which the underlying signaling pathway or pathways are not yet clearly defined. (Redrawn and modified from Seftor et al., 2012.)

In recent years, a multitude of additional studies linking various angiogenesis promoting factors to VM have been published in a variety of cancers. Vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A), a well characterized promoter of endothelial cell proliferation, survival, and angiogenesis has been linked to VM in both melanoma and ovarian carcinoma. In melanoma, the autocrine secretion of VEGF-A was demonstrated to be necessary for VM primarily through activation of VEGF receptor 1 (VEGFR1) (Vartanian et al., 2011). Activation of VEGFR1 leading to downstream activation of PI3K/Akt pathways is involved in angiogenesis; however, downstream activation of Src and Erk1/2 pathways are involved in promoting tumor cell invasion and migration (Koch et al., 2011). In the case of melanoma, VM appears to be mediated through the activation of PI3K/PKCα downstream of VEGFR1 in cooperation with integrin mediated signaling pathways (Vartanian et al., 2011; Mihic-Probst et al., 2012). Moreover, it has been shown that malignant melanoma initiating cells (MMIC) expressing the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) member ABCB5 display a plastic genotype capable of engaging in VM predominately through VEGFR1 mediated signal transduction pathways (Frank et al., 2011). Addition of VEGF-A to ovarian carcinoma cells promoted the upregulation of VM associated genes including VE-cadherin, EphA2, MMP-2 and MMP-9 (Wang et al, 2008). These data suggest that VEGF-A can stimulate characteristics associated with tumor cell plasticity essential for VM. Indeed, compelling evidence supporting this relationship shows that the induction of VM can override VEGF-A silencing and concomitantly enrich stem cell subpopulations expressing CD133 in melanoma (Schnegg et al., 2015).

Further analyses revealed that COX-2, an enzyme responsible for catalyzing the conversion of arachadonic acid into primarily prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), increases the expression of VEGF through a protein kinase C (PKC) mediated pathway. PGE2 binds to a family of prostanoid receptors (EP1-4) which in turn activate EGF receptor (EGFR) signaling and PKC-dependent Erk1/2 activation (Wu et al., 2010). Signaling through these pathways promotes tumor cell proliferation, invasion, angiogenesis, and in some cases VM (Basu et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2010; Robertson et al., 2010). Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF), a non-inhibitory serpin, has been found to suppress angiogenesis through the inhibition of VEGF/VEGFR-1 signaling, induction of apoptosis, or promotion of tumor cell differentiation (reviewed in Hoshina et al., 2010). PEDF may also inhibit VM as the expression is typically down-regulated in aggressive melanoma; interestingly, knock-down of PEDF expression in nonaggressive melanoma cells induces VM (Orgaz et al., 2009).

Perfusion of the VM extravascular networks is critical for functionality, and, as such, Tissue Factor (TF), TF pathway inhibitor-1 (TFPI -1), and TFPI-2 are important for the initiation and regulation of the coagulation pathways and have all been found to be upregulated in aggressive melanoma (Ruf et al., 2003). The expression and activity of these proteins is thought to not only contribute to the fluid-conducting properties of VM channels but to also support tubular network formation. Further evidence for tumor cells providing vascular perfusion was shown in a sophisticated, molecular barcoded model of breast cancer heterogeneity, which revealed VM as a driver of metastasis with particular focus on SERPINE2 and SLP1 as major contributors to the anticoagulant function of the VM extravascular networks (Wagenblast et al., 2015).

Recent studies have identified the Wnt-β-Catenin pathway (WP) as a regulator of VM in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC). Upregulation of the WP was shown to be one of the key signature pathways associated with TNBC metastasis and functions by specifically regulating VM. This work suggested that the WP could provide an attractive pharmacological target for TNBC by inhibiting VM and the aggressive, metastatic phenotype (De et al., 2013).

Additional work has shown a statistically relevant correlation involving increased expression of the urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) and a poor prognosis in various aggressive cancers, including large-cell lung cancer (LCLC), concurrent with VM formation and metastasis (Li et al., 2015). Experimental evidence indicates that uPAR+ cells sorted from the LCLC H460 cell line were more invasive, migratory and engaged in higher levels of VM on a Matrigel matrix than uPAR- cells and expressed higher levels of vimentin and VE-Cadherin. Furthermore, when uPAR+ cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice, there was a marked increase in tumor growth, induction in VM formation and an increase in liver metastases compared to uPAR- cells.

Most recently, the CD44/c-Met signaling cascade was identified as a major promoter of tumor cell plasticity in VM+ Ewing sarcoma and breast carcinoma (Paulis et al., 2015). Together, these data underscore the complexity and diversity of the signal transduction events that promote and regulate VM in various cancer types, while illuminating novel targets for clinical interventions.

4.2 Hypoxia-related signaling pathways

We have come to appreciate that hypoxia, either persistent or transient, is a hallmark of most solid tumors and can regulate pathways in cellular differentiation, induction/maintenance of stem cell-like characteristics, tumor progression, radio- and chemo-resistance, angiogenesis, and VM -- all markers of poor prognosis in patients (Cao et al., 2013). The HIF complex (comprised of HIF-1β and one HIFα subunit: HIF-1α, HIF-2α or HIF-3α) is a key regulator of oxygen homeostasis in both physiological and pathological environments. Under low oxygen availability, HIF-1α undergoes protein stabilization and translocates into the nucleus where it binds to gene regulatory regions containing hypoxia response elements (HREs) and activates transcription of hypoxia-target genes (reviewed in De Bock et al., 2011; Benizri et al., 2008). In particular, hypoxia and subsequent HIF overexpression in tumor cells induces the expression of gene products that are involved in angiogenesis (e.g. VEGF) -- is essential for cell viability, tumor growth, and metastasis. Recently, hypoxia has also been shown to induce VM in hepatocellular carcinoma, Ewing sarcoma, and melanoma, with strong evidence implicating MEK/ERK pathway (Huang et al., 2015). In addition, hypoxia can induce a dedifferentiated phenotype in breast carcinoma (reviewed in Kirschmann, et al., 2012). Pertinent to VM, hypoxia can either directly modulate VEGF-A, VEGFR1, EphA2, Twist, Nodal, osteopontin (OPN), and COX-2 gene expression (via HIF/HRE binding), or indirectly modulate VE-cadherin, tissue factor (TF), and PEDF expression via activation of an intermediary protein that regulates gene transcription or post-transcriptional protein processing (Fernandez-Barral, et al., 2012). In addition, hypoxia can modulate the expression of Notch-responsive genes via HIF-1α stabilization of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) protein and subsequent activation of genes with Notch-responsive promoters, including Nodal (also associated with stem cells, like Notch). This non-canonical crosstalk between HIF-1α and Notch signaling pathways is thought to promote an undifferentiated cell state, further illuminating the possible etiology of tumor cell plasticity underlying VM. Another mechanism in which hypoxia can promote VM is through the generation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS). Redox-dependent stabilization of HIF-1α and induction of VM has been shown in melanoma (Comito et al., 2011). These studies demonstrating hypoxia-induced VM and VM-associated genes highlight the critical role for hypoxia in tumor progression and possibly the initiation of transformation. Indeed, treatment with select anti-angiogenic agents, which inhibit tumor perfusion and increase intratumoral hypoxia, have demonstrated increased metastasis and formation of VM (Xu et al., 2012; Ebos et al., 2009; De Bock et al., 2011).

4.3 Embryonic and/or stem cell pathways

Defined pathways that regulate stem cell behavior and pluripotency also function in tumor cell plasticity and contribute to the formation of VM by select tumor cell subpopulations. Two pathways critical both for embryonic stem cell regulation and tumor cell behavior are the Notch and Nodal signaling pathways (Strizzi et al., 2009a). Importantly, crosstalk between these pathways regulates tumor cell aggressiveness and VM network formation (Hardy et al., 2010).

As a brief overview, Nodal signaling modulates vertebrate embryogenesis and functions in embryonic stem cell pluripotency and left-right asymmetry determination (Schier, 2003). Nodal is generally absent from adult tissues, but is reactivated in aggressive cancers (Topczewska et al., 2006; Postovit et al., 2008; Strizzi et al., 2012). Nodal is a secreted growth factor of the Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGFbeta) superfamily and activates signaling via binding to activin-like kinase receptors, types I (ALK4/5/7) and II (ActRIIB) (Schier, 2003; Topczewska et al., 2006). Nodal can signal with or without the coreceptor, Cripto-1, to propagate downstream signaling through Smad2/3 and activate a transcriptional program typically including Nodal and its antagonist, Lefty. Importantly, aggressive cancer cells express Nodal but not Lefty, since the Lefty promoter is heavily methylated (Costa et al., 2009). This lack of intrinsic regulatory control enables Nodal signaling to proceed unchecked, and promotes aggressive tumor cell behavior and plasticity (Schier, 2003; Topczewska et al., 2006; Postovit et al., 2008). Nodal is expressed in melanoma cells contributing to VM structures (McAllister et al., 2010), and more broadly Nodal has been reported in a variety of additional cancer types, including carcinomas of the breast, colon, ovary, pancreas, prostate, testis, and bladder, leukemia, gliomas, and neuroblastoma (for review, see Strizzi et al., 2015). Targeting ALK receptor activation with chemical inhibitors or Nodal with neutralizing antibodies or using Lefty diminishes the ability of aggressive tumor cells to engage in VM on 3D matrices and in vivo as well (Topczewska et al., 2006; Strizzi et al., 2009b; Strizzi et al., 2015).

The highly conserved Notch signaling pathway functions in stem cell differentiation and self-renewal in various niches of embryonic and adult tissues (Liu et al., 2010). Single transmembrane Notch receptors (Notch1-4) are typically activated by a membrane-tethered ligand (DLL1/2/4 or JAG1/2) on an adjacent cell. Binding triggers proteolytic cleavage events that release the Notch intracellular domain (ICD) into the cytoplasm (Strizzi et al., 2009a). The ICD associates with a transcription factor complex to activate transcription of downstream target genes. During embryonic body plan establishment, Notch signaling regulates Nodal gene expression to direct left-right axis determination (Krebs et al., 2003; Raya et al., 2003). Importantly, crosstalk between Notch and Nodal is recapitulated in melanoma, where Notch4 signaling controls Nodal gene expression in specific subpopulations to regulate tumor cell aggressiveness and plasticity including VM (Hardy et al., 2010). Targeting Notch4 activity with function blocking antibodies diminished in vitro VM formation concurrent with a reduction in VE-cadherin expression (Hardy et al., 2010). Importantly, VM network formation and VE-cadherin expression could be rescued by recombinant Nodal protein. Since VM represents an alternative mechanism for tumor perfusion, targeting the Notch4-Nodal signaling axis has potential for treatment strategies.

Other critical embryonic stem cell-associated genes overexpressed in aggressive VM cancer cells, such as non-small cell lung cancer, are OCT4 and SOX2, which are regulated by YAP1 and provide new insights into the plasticity underlying VM (Bora-Singhal et al., 2015). Especially germane to contemplating new targeting strategies are the key observations from several studies demonstrating a clear association of VM tumor cells expressing several stem cell markers cited above in addition to CD133 concomitant with ABCB5 drug resistance protein (Frank et al., 2011; Lai et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2014; Lezcano et al., 2014;). Furthermore, emerging evidence indicates that conventional therapies are not effectively targeting these stem cell subpopulations, rather they are leading to their enhanced selection and growth resulting in rampant tumor progression (Hardy et al., 2015). Thus, these studies will be highly informative for combinatorial strategies using conventional and targeted approaches.

5. Targeting vascular mimicry using a novel agent, CVM-1118

5.1 Background chemistry of CVM-1118

CVM-1118 is a small molecular compound, currently under clinical development for anti-cancer treatment with particular interest in targeting VM. It is classified as a phenyl-quinoline derivative with molecular weight of ∼360, where the phenyl-quinoline chemophore was first identified from the plant of Rutaceae. This core structure has been demonstrated with potent anti-neoplastic and anti-mutagenic properties (Huang, et al., 1983; Cheng, 1986). A series of structure-based modifications were then made to synthesize compounds with better cytotoxicity against cancer cells. CVM-1118, a compound with high potency and good solubility, was thus selected from a group of derivatives for further development as an anti-cancer drug.

The anti-cancer activity of CVM-1118 was tested using the NCI60 screening assay. The results showed that CVM-1118 inhibited cancer cell growth in approximately 87% of cell lines tested with the average GI50 value <100 nM. COMPARE analysis using the GI50 results by the NCI was also performed. Interestingly, it did not show close correlation with any standard cancer drugs presented in the NCI60 screen database, suggesting that a novel mechanism of action may be involved for the cytotoxic effect of CVM-1118 in cancer cells.

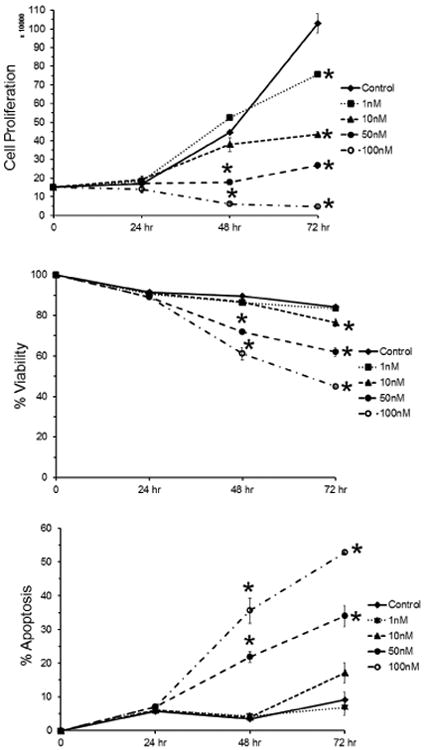

5.2 Effects of CVM-1118 on tumor cell proliferation, percent viability and percent apoptosis

An analysis of the effect of CVM-1118 on the proliferation and percent viability, apoptosis and cell debris (representing dead cells) was performed on human melanoma cells either untreated (Control) or treated with 1, 10, 50 and 100 nM of CVM-1118 using flow cytometry (Guava Easycyte HT; Millipore) with Guava Viacount and Nexin reagents. The melanoma cells (1 × 105) were treated with various concentrations of CVM-1118 for 24, 48 and 72 hr, and subsequently their proliferation, percent viability and percent apoptosis determined compared to untreated cells in triplicate. A representative finding shown in Figure 2 reveals a significant (p<0.05) reduction in proliferation by cells treated with 50 and 100 nM of CVM-1118 after 24 hr and in the cells treated with 10, 50 and 100 nM after 48 and 72 hr. While viability was significantly reduced by CVM-1118 at 10, 50 and 100 nM after 24, 48 and 72 hr of treatment, all concentrations of CVM-1118 (including 1 nM) increased the percent of apoptosis after 24 hr, and after 48 and 72 hr for the cells treated with 50 and 100 nM of CVM-1118.

Fig. 2.

Flow cytometric analysis (Guava) was used to determine viability, proliferation and apoptosis of 1 × 105 human melanoma cells without (Control) and after treatment with 1, 10 and 50 nM CVM-1118 for 24, 48 and 72 hr.

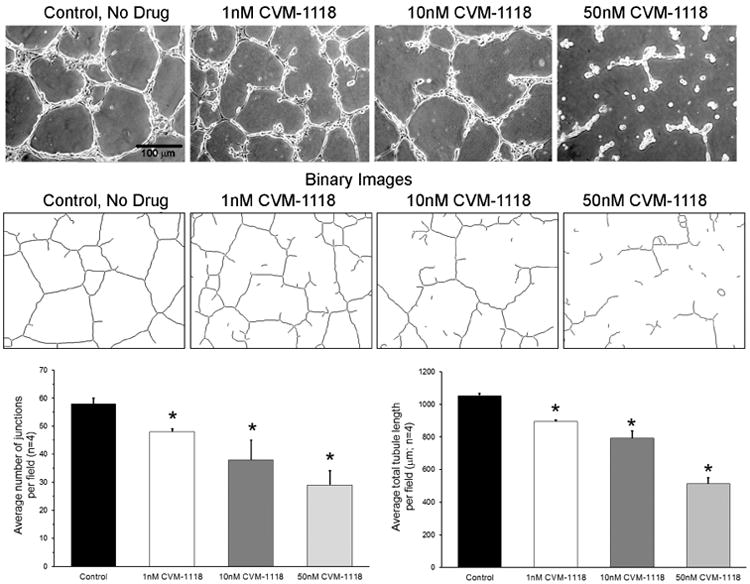

5.3 Inhibition of vascular mimicry by CVM-1118

To evaluate the effect of CVM-1118 on VM in vitro, standard VM assays were performed using 3-dimensional matrices prepared with Matrigel (BDBiosciences) in 12-well culture dishes. Human melanoma cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were plated onto the matrices without (Control) or with CVM-1118 at concentrations of 1, 10 or 50 nM. VM tubular network formation was then observed after 24 hr and images captured digitally using an inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss) with a 10× objective (100× final magnification) and Hitachi HV-C20 CCD camera (Hitachi Denshi Ltd.). The images from four different fields from the Control and treated cultures were then analyzed using the AngioSys software package (TCS CellWorks, Ltd.) assessing the number of junctions and tubules, as well as the total tubule length, determined for each field with the average, standard error and significance determined using Excel. Figure 3 shows representative images from the Control and each CVM-1118 treated group along with the resulting binary image generated for its subsequent analysis. The data demonstrate a dose dependent, statistically significant decrease in the number of junctions and average total tubule length (per observed field) in the samples treated with 1, 10 and 50 nM of CVM-1118 compared to the Control sample. While the ability of CVM-1118 to inhibit VM is clearly visible in the images, detailed analysis supports the concept that this inhibition is dose dependent and can be correlated with a breakdown in the cells' ability to form branching, tubular networks characteristic of VM.

Fig. 3.

Human melanoma cells were cultured in 3-dimensional Matrigel matrices without (Control) or with 1, 10 and 50 nM CVM-1118. After 24 hr, four images per treatment were digitally captured and representative images shown here. These images were then converted to binary images (as shown) and analyzed using the Angiosys software to determine the average number of junctions and average total tubule length per field for the four images per parameter. Statistically significant changes (p<0.05) are marked with an * in the bar graphs. (Magnification 100×; scale bar = 100 μm.)

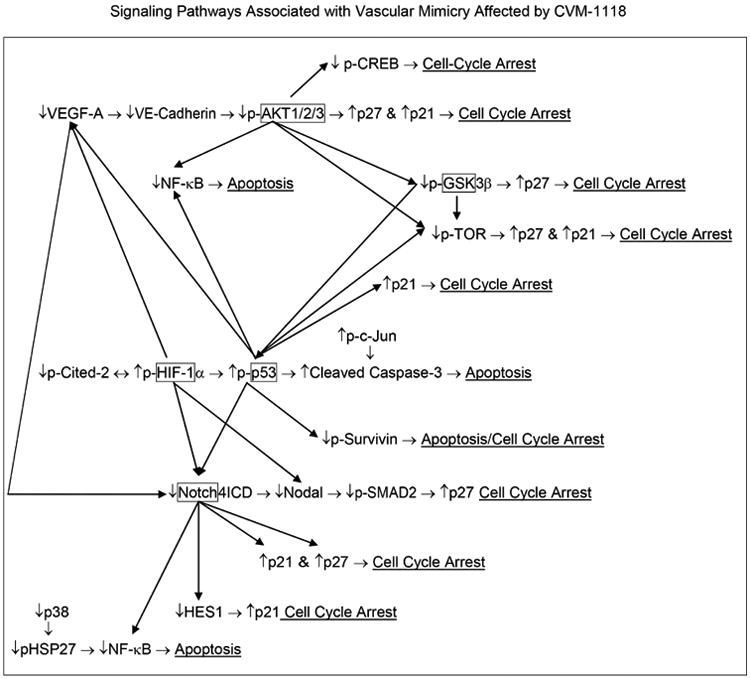

5.4 Pathways affected by CVM-1118

The key signaling pathways underlying VM described above and highlighted in Figure 1 were further interrogated after treatment with CVM-1118 in human melanoma cells. Using a combination of qRT-PCR analyses, together with protein arrays, changes were measured in human phospho-MAPK/phospho-kinases and cell stress checkpoints, in addition to apoptosis regulators. A compilation of the major findings generated in response to CVM-1118 treatment are presented as cascading and overlapping signaling pathways in Figure 4. The major overall effect of CVM-1118 on human melanoma cells at the mRNA level is down-regulation of the stem cell-associated genes Nodal (and downstream pSMAD2), Notch4 ICD and HES1, in addition to the vascular signaling-associated gene VEGF-A (annotated in Table 1) -- resulting in suppression of VM. Additional analyses of CVM-1118 treatment effects at the protein level revealed noteworthy increases in (phosphorylated, designated p-) p-HIF-1α, p-p27, and p-c-Jun, collectively demonstrating stabilization of proteins underlying the hypoxia response, cell cycle arrest, growth inhibition, and apoptotic events, respectively (Table 2). Equally significant are the decreases in p-Cited-2, p-Survivin, p-CREB, p-HSP27, p-38α, p-NF-κB, p-AKT1/2/3, p-TOR, and p-GSK-3α/β, which portray a global diminution in tumor growth, anti-apoptotic check points, cell proliferation, ERK and p38 signaling, inflammatory response pathways, cell differentiation, and protein synthesis (annotated in Table 2). Lastly, the human apoptosis array disclosed key findings related to the effects of CVM-1118 treatment, most notably resulting in increased cleaved Caspase-3, p-p53, p27 and p21, indicating molecular crosstalk involving caspase activation of apoptosis by p53 with repression of VEGF and Notch, and activation of target genes that initiate cell death (Bax) and cause growth arrest (p21). In addition, the increased p27 results in inhibition of cyclin E-CDK2 and acts as a tumor suppressor (annotated in Table 3). Collectively, the molecular analyses of the key signaling pathways affected by CVM-1118 further elucidate critical checkpoints required to suppress the VM tumor cell phenotype in melanoma associated with poor clinical outcome.

Fig. 4.

Diagram of signaling pathways associated with VM that are affected by CVM-1118. After treating human melanoma cells with CVM-1118, changes in the mRNA, protein expression and phosphorylation of specific members of these different pathways were examined by q-RT-PCR, Western blot analyses, and the R&D Systems Proteome Profiler Antibody Arrays (i.e. Human Apoptosis, Human Phospho-Kinase, Human Phospho-MAPK and Human Cell Stress Arrays).

Table 1. * qRT-PCR - Human Melanoma Cells + CVM-1118.

| Decrease in mRNA | |

|---|---|

| ↓Decrease | Notes |

| Nodal | TGF-β family member, binds to ALK4/5/7 and ActRllB/TGF-β- R2 activin-like kinase receptors to signal through SMAD2/3. Blocking Nodal signaling blocks VM. (Hardy et al., 2010; Kirschmann et al. 2012) |

| pSMAD2 | Published that decrease in Nodal results in a decrease in p- SMAD2 signaling and decrease in VM. (Hardy et al., 2010) |

| Notch4 ICD | Published that knock-down Notch4 results in decrease in Nodal expression and decrease in VM. Notch binding to its receptor results in cleavage of Notch, releasing an Intracellular domain (NICD) which translocates into the nucleus and regulates the expression of a number of targets, including Nodal (Hardy et al., 2010; Kirschmann et al., 2012). Notch is downstream of VEGF signaling (Takeshita et al., 2007). Notch1 activates p21-induced cell-cycle arrest tumor model (Liu et al., 2015). Increase in Notch has been associated with a decrease in p27 (Sharma et al., 2010). p53 regulates Notch activation (Laws and Osborne, 2004). Notch is a p53 target with a role in human tumor suppression (Lefort et al., 2007). |

| HES1 | A target protein of Notch (Sharma et al., 2010) and plays a role in cellular differentiation, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and self-renewal, maintaining cancer stem cells (CSC), metastasis and antagonizing drug-induced apoptosis (Liu et al., 2015). HES1 transcriptionally represses p21 (Liu et al., 2015)). |

| VEGF-A | VEGF treatment of cells results in Notch1 cleavage and increase in HES1 expression (Takeshita et al., 2007). WT p53 represses VEGF expression (Ghahremani et al., 2013). |

qRT-PCR performed in triplicate with primers previously published (Hardy et al., 2010), and key data further validated by Western blot analyses.

Table 2. *Human Melanoma Cells +CVM-1118: Human Phos-MAPK/Phos-Kinases & Cell Stress Arrays.

| Increase or Decrease in Phosphorylation of Proteins | ||

|---|---|---|

| ↑ Increase | ↓ Decrease | Notes |

| p-HIF-1α ↔ | p-Cited-2 | ↑HIF-1α ↔ Cited-2↓;↓HIF-1α ↔ Cited-2↑ HIF-1α and Cited-2 form a negative feedback loop for HIF-1 activity (Bakker et al., 2007; Du and Yang, 2012). Ectopic Cited-2 expression enhanced tumor growth in nude mice (Du et al., 2012, Du and Yang, 2012). Cited-2 functions as a molecular switch of TGF-a and TGR-β-induced growth control (Chou et al., 2012). Deletion of Cited-2 in mESC results in abnormal mitochondrial morphology and impaired glucose metabolism (Li et al., 2014). Hypoxia induces VM in a number of different tumors. Protein stabilization and nuclear localization of HIF-1α and binding to hypoxia response elements (HRE) in promoters and enhancers of effector genes occurs in response to low oxygen, oncogenes, or inactivated tumor suppressor genes. HIF-1/HRE has been shown to directly modulate VEGF-A, VEGFR, EphA2, Twist, Nodal and COX-2 gene expression, or indirectly modulate VE-Cadherin and Tissue Factor (TF) expression (Kirschmann et al., 2012). It can also modulate the expression of Notch-responsive genes, specifically, stabilizing the NICD protein which interacts with HIF-1α and activates genes with Notch-responsive promotors, including Nodal (Quillard and Charreau et al., 2013) |

| p-p27 (T198) | p27 is an inhibitor of cyclin E-CDK2 and acts as a tumor suppressor. Phosphorylation of p27 at serine 10 facilitates nuclear export and p27's subsequent proteolysis. Phosphorylation of other sites on p27 impairs the CDK2 inhibitory action of p27. Phosphorylation on T157/T198 impairs import of p27 into the nucleus and promotes cyclin D1-CDR4-p27 complex assembly but, needs activation of the complex by phosphorylation of p27 by Src (Larrea et al., 2008; Wander et al., 2011). | |

| p-c-Jun (S63) | Phosphorylation of c-Jun (Ser63) is associated with apoptosis upstream of Caspase-3 activation (Lei et al., 2004; Ghahremani et al., 2013). | |

| p-Survivin | An anti-apoptotic protein (smallest member of the “Inhibitor of Apoptosis” [IAP] gene family). Plays a role in apoptosis, cell cycle, chromosome movement, mitosis and cellular stress response. Several tumor suppressors (WT p53, Rb) repress Survivin expression while Ras, STAT3 and Wnt-2 up-regulate its expression. Up-regulation of Survivin inhibits autophagy while down- regulation promotes cell autophagy. Can inhibit apoptosis by inhibiting activity of different caspases (Soleimanpour and Babaei, 2015), and is associated with regulating VM (Sanhueza et al., 2015). | |

| p-CREB | CREB can be phosphorylated and activated by AKT (Yamada et al., 2015). p-AKT1/2/3 ↓. phosphorylation of CREB promotes interaction with coactivator CBP/p300 inducing cell proliferation, cell-cycle progression and survival of myeloid cells. (Shankar et al., 2005; Braeuer et al., 2011). | |

| pHSP27 | An antiapoptotic protein (Li and Srivastava, 2003). Knockdown of HSP27 decreases the nuclear translocation as well as the activity of NF-κB (Guo et al., 2008; Wei et al., 2011). Phosphorylation of HSP27 inhibits TNF-α induced apoptosis via regulating TAK1 ubiquitination and activation of p38 and ERK signaling (Qi et al., 2014). | |

| p-38α | More than 100 proteins can be directly phosphorylated by p38 and a significant proportion of them are involved in the regulation of gene expression (Igea and Nebreda, 2015). Rho activation was found dependent on p38 MAPK activity and the presence of HSP27, which is phosphorylated downstream of p38 after arachidonic acid treatment (Garcia et al., 2009). Activation of p38 can lead to the phosphorylation of HSP27 (Huot et al., 1998). | |

| p-NFκB | NF-κB is the key transcription factor involved in the inflammatory pathway (Chaturveda et al., 2011). Translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus and activity decreases after knockdown of HSP27 (Guo et al., 2008; Wei et al., 2011). The NF-κB pathway is a major downstream target of Notch 1 (Vilimas et al., 2007). WT p53 has been shown to antagonize NF-κB activity (Meylan et al., 2009). | |

| p-AKT1/2/3 | Activates NF-κB (Ozes et al., 1999). mTOR is the most important downstream effector and phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 kinase, directly leading to protein translation and cell cycle progression. AKT phosphorylates and deactivates GSK-3β and can downregulate p27 and p21 and also result in the reduction in p53 (Zhang et al., 2015). | |

| p-TOR | Loss of p53 promotes mTORC2 activation (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). Following Akt activation, mTOR can be phosphorylated and the activation of this downstream pathway can be important for regulating cell proliferation and differentiation, protein synthesis as well as cell metabolism (Follo et al., 2015). p53 inhibits mTOR activity leading to cell cycle arrest (Jiang & Liu, 2008) GSK activation (dephosphorylation) promotes phosphorylation of TSC2 and β-Catenin, and p-TSC2 suppresses mTOR activity (Hsein et al., 2015). | |

| p-GSK-3α/β | Activated AKT phosphorylates GSK resulting in GSK inactivation (Takahashi-Yanaga, 2013). GSK-3 phosphorylates p27 to enhance its stability (Surjit and Lai, 2007). GSK activation (dephosphorylation) promotes phosphorylation of TSC2 and β-Catenin, and p-TSC2 suppresses mTOR activity (Hsein et al., 2015). | |

Protein analyses performed in triplicate using R&D Systems Human Phospho-MAPK/Phospho-Kinases & Cell Stress Arrays.

Table 3. *Human Melanoma Cells +CVM-1118: Human Apoptosis Array.

| Increase in Proteins | |

|---|---|

| ↑ Increase | Notes |

| Cleaved Caspase-3 | p53 induces apoptosis by caspase activation (Schuler et al., 2000). |

| p-p53 | Phosphorylation stabilizes p53, a tumor suppressor protein and transcription factor that activate target genes that initiate cell death (Bax) and cause growth arrest (e.g. p21; Piret et al., 2002; Abukhdier and Park, 2009). p53 induces apoptosis by caspase activation (Schuler et al., 2000). WT p53 represses VEGF expression (Ghahremani et al., 2013). p53 regulates Notch activation (Laws and Osbone, 2004). Notch is a p53 target with a role in human tumor suppression (Lefort et al., 2007). |

| p27 | p27 is an inhibitor of cyclin E-CDK2 and acts as a tumor suppressor (Wander et al., 2011; Larrea et al., 2008). Cytokine withdrawal (activated protein kinase B [AKT]) induces apoptosis preceded by an upregulation in p27 and decrease in cell cycle (Djikes et al., 2002). |

| p21 | Directly regulated by p53, p21 functions by inhibiting cyclin dependent kinases, though its function and location is regulated by phosphorylation of different sites on the protein (Abukhdier and Park, 2009). |

Protein analyses performed in triplicate using R&D Systems Human Apoptosis Array.

6. Conclusions

This review of VM across a broad range of cancers provides only the highlights of key findings pertinent to its functional and translational relevance in association with an aggressive and metastatic phenotype. The molecular pathways underlying VM have illuminated new candidates for the development of innovative treatment strategies that target tumor cell plasticity and the metastatic properties affiliated with disease recurrence and drug resistance. Further confounding our ability to effectively eradicate cancer is the challenge associated with heterogeneous subpopulations comprising tumors along with a complex, diverse vasculature supply. Moreover, the unintended consequences of hypoxia induced by rapid tumor growth or by some conventional therapies may serve as a catalyst for the VM and cancer stem cell phenotype. Therefore, it seems prudent, and certainly timely, to consider the application of new agents, such as CVM-1118 -- to target VM pathways associated with the stem cell phenotype and resistant to most conventional agents. Further studies are warranted to expand the assessment of CVM-1118 in other aggressive cancers expressing VM to better understand its full potential. Targeting VM with specific molecular compounds used in a combinatorial manner with front-line therapies may hold the greatest promise in the war on cancer.

Acknowledgments

The research findings presented in this review were funded in part by: NIH/NCI grants R37 CA59702, TaiRx, Inc. research contract, and a gift from the Robert Kriss Family.

Abbreviations

- ALK4/5/7

Activin-like kinases4/5/7

- COX-2

Cyclooxygenase-2

- DLL1/2/4

Delta-like ligand1/2/4

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- Eph

Erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular

- EphA2

Erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular tyrosine kinases receptor-2

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- Erk1/2

Extracellular regulatory kinase 1 and 2

- FAK

Focal Adhesion Kinase

- JAG1/2

Jagged

- Ln5 γ2 chain

Laminin 5 gamma 2 chain

- LCLC

Large-cell lung cancer

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinase

- OCT4

Octamer-binding transcription factor-4

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PEDF

Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- EP3

Prostaglandin E receptor EP3 subtype

- EP1-4

Prostanoid receptors

- PKC

Protein kinase C

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- known as SOX2

Sex-determining region box-2

- siRNA

Small inhibitory RNA

- TFPI-1

TF pathway inhibitor-1

- TFPI -2

TF pathway inhibitor-2

- TF

Tissue Factor

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor beta

- TNBC

Triple negative breast cancer

- uPAR

Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor

- VE-Cadherin

Vascular Endothelial Cadherin

- VEGF-A

Vascular endothelial growth factor-A

- VEGFR1

VEGF receptor 1

- VM

Vascular mimicry or vasculogenic mimicry

- WP

Wnt-β-Catenin pathway

- YAP1

YES associated protein

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Mary Hendrix, Elisabeth Seftor, and Richard Seftor, hold patents on Nodal, Lefty and Notch4 therapeutics; Du-Shieng Chien, Yi-Wen Chu, and Jun-Tzu Chao are employees of TaiRx, Inc., where CVM-1118 is currently under development.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abukhdeir AM, Park BH. P21 and p27: roles in carcinogenesis and drug resistance. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2009;10:e19. doi: 10.1017/S1462399408000744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker WJ, Harris IS, Mak TW. FOXO3a is activated in response to hypoxic stress and inhibits HIF-1-induced apoptosis via regulation of CITED2. Mol Cell. 2007;28:941–953. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu GD, Liang WS, Stephan DA, Wegener LT, Conley CR, Pockaj BA, et al. A novel role for cyclooxygenase-2 in regulating vascular channel formation by human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R69. doi: 10.1186/bcr1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benizri E, Ginouves A, Berra E. The magic of the hypoxia-signaling cascade. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(7-8):1133–1149. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7472-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittner M, Meltzer P, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Seftor EA, Hendrix MJC, et al. Molecular classification of cutaneous malignant melanoma by gene expression: Shifting from a continuous spectrum to distinct biologic entries. Nature. 2000;406:536–540. doi: 10.1038/35020115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora-Singhal N, Nguyen J, Schall C, Perumal D, Singh S, Coppola D, et al. YAP1 regulates OCT4 activity and SOX2 expression to facilitate self-renewal and vascular mimicruy of stem-like cells. Stem Cells. 2015;33(6):1705–1718. doi: 10.1002/stem.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braeuer RR, Zigler M, Villares GJ, Dobroff AS, Bar-Eli M. Transcriptional control of melanoma metastasis: The importance of the tumor microenvironment. Sem Cancer Biol. 2011;21:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Bao M, Miele L, Sarkar FH, Wang Z, Zhou Q. Tumour vasculogenic mimicry is associated with poor prognosis of human cancer patients: A system review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3914–3923. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.07.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473(7347):298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaturvedi MM, Sung B, Yadav VR, Kannappan R, Aggarwal BB. NF-κB addiction and its role in cancer: ‘one size does not fit all’. Oncogene. 2011;30:1615–1630. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CC. A common structural pattern among many biologically active compounds of natural and synthetic origin. Med Hypotheses. 1986;20(2):157–72. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(86)90122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou YT, Hsieh CH, Chiou SH, Kao YR, Lee CC, et al. CITED2 functions as a molecular switch of cytokine-induced proliferation and quiescence. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19(12):2015–2028. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comito G, Calvani M, Giannoni E, Bianchini R, Calorini L, Torre E, et al. HIF-1α stailization by mitochondrial ROS promotes Met-dependent invasive growth and vasculogenic mimicry in melanoma cells. Free Redic Biol Med. 2011;51(4):893–904. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa FF, Seftor EA, Bischof JM, Kirschmann DA, Strizzi L, Arndt K, et al. Epigenetically reprogramming metastatic tumor cells with an embryonic microenvironment. Epigenomics. 2009;1(2):387–398. doi: 10.2217/epi.09.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De P, Carlson J, Leyland-Jones B, Dey N. Wnt-β-Catenin pathway regulats vascular mimicry in triple negative breast cancer. J Cytol Histol. 2013;4:198. [Google Scholar]

- De Bock K, Mazzone M, Carmeliet P. Antiantiogenic therapy, hypoxia, and metastasis: risky liaisons, or not? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:393–404. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey N, De P, Leyland-Jones B. Evading anti-angiogenic therapy: resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy in solid tumors. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7(10):1675–1698. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demou Z, Hendrix MJC. Microgenomics profile of the endogenous angiogenic phenotype in subpopulations of aggressive melanoma. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105:562–573. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkers PF, Birkenkamp KU, Lam EWF, Thomas NSB, Lammers JWJ, Koenderman L, et al. FKHR-L1 can act as a critical effector of cell death induced by cytokine withdrawal: protein kinase B-enhanced cell survival through maintenance of mitochondrial integrity. J Cell Biol. 2002;156(3):531–542. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döme B, Hendrix MJC, Paku S, Tovari J, Timar J. Alternative vascularization mechanisms in cancer: Pathology and therapeutic implications. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1–15. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Yang YC. HIF-1 and its antagonist Cited2. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(13):2413–2414. doi: 10.4161/cc.20803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Chen Y, Q Li, Han X, Cheng C, Wang Z, et al. HIF-1α deletion partially rescues defects of hematopoietic stem cell quiescence caused by Cited2 deficiency. Blood. 2012;119(12):2789–2798. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-387902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebos JM, Lee CR, Cruz-Munoz W, Bjarnason GA, Christensen JG, Kerbel RS. Accelerated metastasis after short-term treatment with a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(3):232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Barral A, Orgaz JL, Gomez V, del Peso L, Calzada MJ, Jiménez B. Hypoxia negatively regulates antimetastatic PEDF in melanoma cells by a hypoxia inducible factor-independent, autophagy dependent mechanisms. PLos One. 2012;7(3):e32989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032989. Epub 2012 Mar 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Clinical applications of research on angiogenesis. Seminars in Medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. New Engl J Med. 1995;333:1757–1763. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follo MY, Manzoli L, Poli A, McCubrey JA, Cocco L. PLC and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in disease and cancer. Adv Biol Reg. 2015;57:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank NY, Schatton T, Kim S, Zhan Q, Wilson BJ, Ma J, et al. VEGFR-1 expressed by malignant melanoma-initiating cells is required for tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2011;71(4):1474–1485. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MC, Ray DM, Lackford B, Rubino M, Olden K, Robert JD. Arachidonic acid stimulates cell adhesion through a novel p38 MAPK-RhoA signaling pathway that involves heat shock protein 27. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(31):20936–20945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghahremani MF, Goosens S, Haigh JJ. The p53 family and VEGF regulation. Cell Cycle. 2013;12(9):1331–1332. doi: 10.4161/cc.24579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo K, Kang NX, Li Y, Sun L, Gan L, Cui FJ, et al. Regulation of HSP-27 on NF-kB pathway activation may be involved in metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma cells apoptosis. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy KM, Kirschmann DA, Seftor EA, Margaryan NV, Postovit LM, Strizzi L, Hendrix MJC. Regulation of the embryonic morphogen Nodal by Notch4 facilitates manifestation of the aggressive melanoma phenotype. Cancer Res. 2010;70(24):10340–10350. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy KM, Strizzi L, Margaryan NV, Gupta K, Murphy GF, Scolyer RA, et al. Targeting Nodal in conjunction with Dacarbazine induces synergistic anticancer effects in metastatic melanoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13(4):670–680. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix MJC, Seftor REB, Seftor EA, Gruman LM, Lee LM, Nickoloff B, et al. Transendothelial function of human metastatic melanoma cells: Role of the microenvironment in cell-fate determination. Cancer Res. 2002;62:665–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix MJC, Seftor EA, Hess AR, Seftor REB. Vasculogenic mimicry and tumour-cell plasticity: Lessons from melanoma. Nature Rev Cancer. 2003;3:411–421. doi: 10.1038/nrc1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix MJC, Seftor EA, Meltzer PS, Gardner LM, Hess AR, Kirschmann DA, et al. Expression and functional significance of VE-cadherin in aggressive human melanoma cells: role in vasculogenic mimicry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8018–8023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131209798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix MJC, Seftor EA, Meltzer PS, Hess AR, Gruman LM, Nickoloff BJ, et al. The stem cell plasticity of aggressive melanoma tumor cells. In: Sell S, editor. Stem Cell Handbook. New Jersey: Humana Press Inc; 2000. pp. 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Hess AR, Seftor EA, Gardner LM, Carles-Kinch K, Schneider GB, Seftor REB, et al. Molecular regulation of tumor cell vasculogenic mimicry by tyrosine phosphorylation: role of epithelial cell kinase (Eck/EphA2) Cancer Res. 2001;61:3250–3255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess AR, Hendrix MJC. Focal adhesion kinase signaling and the aggressive melanoma phenotype. Cell Cycle. 2006a;5:478–480. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.5.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess AR, Seftor EA, Gruman LM, Kinch MS, Seftor REB, Hendrix MJC. VE-cadherin regulates EphA2 in aggressive melanoma cells through a novel signaling pathway: implications for vasculogenic mimicry. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006b;5:228–233. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.2.2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess AR, Seftor EA, Seftor REB, Hendrix MJC. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates membrane Type 1-matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) and MMP-2 activity during melanoma cell vasculogenic mimicry. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4757–4762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshina D, Abe R, Yamagishi SI, Shimizu H. The role of PEDF in tumor growth and metastasis. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10:292–295. doi: 10.2174/156652410791065327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HY, Shen CH, Lin RI, YM, Huang SY, Wang YH, et al. Cyproheptadine exhibits antitumor activity in urothelial carcinoma cells by targeting GSKβ to suppress mTOR and β-catenin signaling pathways. Cancer Lett. 2015;370:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Xiao E, Huang M. MEK/ERK pathway is positively involved in hypoxia-induced vasculogenic mimicry formation in hepatocellular carcinoma which is regulated negatively by protein kinase A. Med Oncol. 2015;31(1):408–419. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang MT, Wood AW, Newmark HL, Sayer JM, Yagi H, Jerina DM, et al. Inhibition of the mutagenicity of bay-region diol-epoxides of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by phenolic plant flavonoids. Carcinogenesis. 1983;4(12):1631–1637. doi: 10.1093/carcin/4.12.1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huot J, Houle F, Rousseau S, Deschesnes RG, Shah GM, Landry J. SAPK2/p38-dependent F-actin reorganization regulates early membrane blebbing during stress-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1998;143(5):1361–1373. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.5.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igea A, Nebreda AR. The stress kinase p38α as a target for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2015;75(19):3997–4002. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang BH, Lui LZ. Role of mTOR in anticancer drug resistance: Perspectives for improved drug treatment. Drug Resist Updates. 2008;11:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschmann DA, Seftor EA, Hardy KM, Seftor REB, Hendrix MJC. Molecular pathways: Vasculogenic mimicry in tumor cells: Diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(10):2726–2732. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch S, Tugues S, Li X, Gualandi L, Claesson-Welsh L. Signal transduction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Biochem J. 2011;437:169–183. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs LT, Iwai N, Nonaka S, Welsh IC, Lan Y, Jiang R, et al. Notch signaling regulates left-right asymmetry determination by inducing Nodal expression. Genes Dev. 2003;17(10):1207–1212. doi: 10.1101/gad.1084703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CY, Schwartz BE, Hsu MY. CD133+ melanoma subpopulations contribute to perivascular niche morphogenesis and tumorigenicity through vasculogenic mimicry. Cancer Res. 2012;72(19):5111–5118. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrea MD, Liang J, Da Silva T, Hong F, Shao SH, Han K, et al. Phosphorylation of p27KIP1 regulates assembly and activation of cyclin D1-Cdk4. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(20):6462–6472. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02300-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laws AM, Osborne BA. p53 regulates thymic Notch-1 activation. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34(3):726–734. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefort K, Mandinova A, Ostano P, Kolev V, Calpini V, Kolfschoten I, et al. Notch1 is a p53 target gene involved in human keratinocyte tumor suppression through negative regulation of ROCK1/2 and MRCKα kinases. Genes Dev. 2007;21(5):562–577. doi: 10.1101/gad.1484707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei L, Feng Z, Porter AG. JNK-dependent phosphorylation of c-jun on serine 63 mediates nitric oxide –induced apoptosis of neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(6):4058–4065. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310415200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezcano D, Kleffel S, Lee N, Larson AR, Zhan Q, DoRosario A, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma expresses vasculogenic mimicry: Demonstration in patients and experimental manipulation in xenografts. Lab Invest. 2014;94(10):1092–1102. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Hakimi P, Liu X, Yu WM, Ye F, Fujioka H, et al. Cited2, a transcriptional modulator protein, regulates metabolism in murine embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2014;389(1):251–263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.497594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Sun B, Zhao X, Zhang D, Wang X, Zhu D, et al. Supopulations of uPAR+ contribute to vasculogenic mimicry and metastasis in large cell lung cancer. Exp Mol Pathol. 2015;98:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Srivastava P. Heat-shock proteins. Curr Protocols Immunol. 2003;S58:A.1T.1–A.1T.6. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.ima01ts58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Sato C, Cerletti M, Wagers A. Notch signaling in the regulation of stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:367–409. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZH, Dai XM, Du B. Hes1: a key role in stemness, metastasis and multidrug resistance. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16(3):353–359. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2015.1016662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniotis AJ, Folberg R, Hess A, Seftor EA, Gardner LMG, Pe'er J, et al. Vascular channel formation by human melanoma cells in vivo and in vitro: Vasculogenic mimicry. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:739–752. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65173-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister JC, Zhan Q, Weishaupt C, Hsu MY, Murphy GF. The embryonic morphogen, Nodal, is associated with channel-like structures in human malignant melanoma xenografts. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37(Suppl 1):19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2010.01503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan E, Dooley AL, Feldser DM, Shen L, Turk E, Ouyang C, et al. Requirement for NF-κB signaling in a mouse model of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2009;462(5):104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature08462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihic-Probst D, Ikenberg K, Tinguely M, Schrami P, Behnke S, Seifert B, et al. Tumor cell plasticity and angiogenesis in human melanoma. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourad-Zeidan AA, Melnikova VO, Wang H, Raz A, Bar-Eli M. Expression profiling of Galectin-3-depleted melanoma cells reveals its major role in melanoma cell plasticity and vasculogenic mimicry. Am J Pathol. 173(6):1839–1852. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgaz JL, Ladhani O, Hoek KS, Fernandez-Barral A, Mihic D, Aguilera O, et al. Loss of pigment epithelium-derived factor enables migration, invasion and metastatic spread of human melanoma. Oncogene. 2009;28:4147–4161. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozes ON, Mayo LD, Gustin JA, Pfiffer SR, Pfiffer LM, Donner DB. NF-κB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires the AKT serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999;401:82–85. doi: 10.1038/43466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulis YW, Huijbers EJ, van der Schaft DW, Soetekouw PW, Pauwels P, Tjan-Heijnen VC, et al. CD44 enhances tumor aggressiveness by promoting tumor cell plasticity. Oncotarget. 2015;6(23):19634–19646. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulis YW, Soetekouw PM, Verheul HM, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Griffioen AW. Signaling pathways in vasculogenic mimicry. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1806:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzella FP, Mazotti M, Bacco AD, Viale G, Nicholson AG, Price R, et al. Evidence for novel non-angiogenic pathway in breast cancer metastasis. Breast Cancer Progression Working Party. Lancet. 2000;355:1787–1788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piret JP, Mottot D, Raes M, Michiels C. Is HIF-1α a pro- or anti-apoptotic protein? Biochem Pharm. 2002;64:889–892. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postovit LM, Margaryan NV, Seftor EA, Kirschmann DA, Lipavsky A, Wheaton WW, et al. Human embryonic stem cell microenvironment suppresses the tumorigenic phenotype of aggressive cancer cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2008;105(11):4329–4334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800467105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Z, Shen L, Zhou H, Jiang Y, Lan L, Luo L, et al. Phosphorylation of heat shock protein 27 antagonizes TNF-α induced HeLa cell apoptosis via regulating TAK1 ubiquitination and activation of p38 and ERK signaling. Cell Sig. 2014;26:1616–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quillard T, Charreau B. Impact of Notch signaling on inflammatory responses in cardiovascular disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(4):6863–6888. doi: 10.3390/ijms14046863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raya A, Kawakami Y, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Buscher D, Koth CM, Itoh T, et al. Notch activity induces Nodal expression and mediates the establishment of left-right asymmetry in vertebrate embryos. Genes Dev. 2003;17(10):1213–1218. doi: 10.1101/gad.1084403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci-Vitiani L, Pallini R, Biffoni M, Todaro M, Invernici G, Cenci T, et al. Tumour vascularization via endothelial differentiation of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Nature. 2010;468:824–828. doi: 10.1038/nature09557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson FM, Simeone AM, Lucci A, McMurray JS, Ghosh S, Cristofanilli M. Differential regulation of the aggressive phenotype of inflammatory breast cancer cells by prostanoid receptors EP3 and EP4. Cancer. 2010;116:2806–2814. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf W, Seftor EA, Petrovan RJ, Weiss RM, Gruman LM, Margaryan NV, et al. Differential role of tissue factor pathway inhibitors 1 and 2 (TFPI-1 and 2) in melanoma vasculogenic mimicry. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5381–5389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanhueza C, Wehinger S, Bennett JC, Valenzuela M, Owen GKI, Quest AFG. The twisted surviving connection to angiogenesis. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:198. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0467-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schier AF. Nodal signaling in vertebrate development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:589–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.041603.094522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnegg CI, Yang MH, Ghosh SK, Hsu MY. Induction of vasculogenic mimicry overrides VEGF-A silencing and enriches stem-like cancer cells in melanoma. Cancer Res. 2015;75(8):1682–1690. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler M, Bossy-Wetzel E, Goldstein JC, Fitzgerald P, Green DR. p53 induces apoptosis by caspase activation through mitochondrial cytochrome c release. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7337–7342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seftor EA, Meltzer PS, Schatteman GC, Gruman LM, Hess AR, Kirschmann DA, et al. Expression of multiple molecular phenotypes by aggressive melanoma tumor cells: role in vasculogenic mimicry. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;44:17–27. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seftor REB, Hess AR, Seftor EA, Kirschmann DA, Hardy KM, Margaryan NV, et al. Tumor cell vasculogenic mimicry: From controversy to therapeutic promise. Am J Pathol. 2012;181(4):1115–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seftor REB, Seftor EA, Koshikawa N, Meltzer PS, Gardner LMG, Bilban M, et al. Cooperative interactions of laminin 5 γ2 chain, matrix metalloproteinase-2, and membrane type-1matrix/metalloproteinase are required for mimicry of embryonic vasculogenesis by aggressive melanoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6322–6327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar DB, Cheung JC, Kinjo K, Federman N, Moore TB, Gill A, et al. The role of CREB as a proto-oncogene in hematopoiesis and in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:351–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Callen S, Zhang D, Singhal PC, Vanden Heuvel GB, Buch S. Activation of Notch signaling pathway in HIV-associated nephropathy. AIDS. 2010;24(14):2161–2170. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833dbc31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soda Y, Myskiw C, Rommel A, Verma IM. Mechanisms of neovascularization resistance to anti-angiogenic therapies in glioblastoma multiforme. J Mol Med. 2013;91:439–448. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1019-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimanpour E, Babaei E. Survivin as a potential target for cancer therapy. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(15):6187–6191. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.15.6187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeg PS. Angiogenesis inhibitors: Motivators of metastasis. Nature Med. 2003;9:822–823. doi: 10.1038/nm0703-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strizzi L, Hardy KM, Margaryan NV, Hillman DW, Seftor EA, Chen B, et al. Potential for the embryonic morphogen Nodal as a prognostic and predictive biomarker in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14(3):R75. doi: 10.1186/bcr3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strizzi L, Hardy KM, Seftor EA, Costa FF, Kirschmann DA, Seftor REB, et al. Development and cancer: at the crossroads of Nodal and Notch signaling. Cancer Res. 2009a;69(18):7131–7134. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strizzi L, Postovit LM, Margaryan NV, Lipavsky A, Gadiot J, Blank C, et al. Nodal as a biomarker for melanoma progression and a new therapeutic target for clinical intervention. Expert Rev Dermatol. 2009b;4(1):67–78. doi: 10.1586/17469872.4.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strizzi L, Sandomenico A, Margaryan NV, Foca' A, Sanguigno L, Bodenstine TM, et al. Effecgts of a novel Nodal-targeting monoclonal antibody in melanoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(33):34071–34086. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Zhao N, Zhao XL, Gu Q, Zhang SW, Che N, et al. Expression and functional significance of Twist1 in hepatocellular carcinoma: its role in vasculogenic mimicry. Hepatology. 2010;51:545–556. doi: 10.1002/hep.23311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surjit M, Lal SK. Glycogen synthase linase-3 phosphorylates and regulates the stability of p27kip1 protein. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(5):580–588. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.5.3899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi-Yanaga F. Activator of inhibitor? GSK-3 as a new drug target. Biochem Pharm. 2013;86:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita K, Satoh M, Li M, Silver M, Limbourg FP, Mukai Y, et al. Critical role of the endothelial Notch1 signaling in postnatal angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;100(1):70–78. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000254788.47304.6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topczewska JM, Postovit LM, Margaryan NV, Sam A, Hess AR, Wheaton WW, et al. Embryonic and tumorigenic pathways converge via Nodal signaling: role in melanoma aggressiveness. Nat Med. 2006;12(8):925–932. doi: 10.1038/nm1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Schaft DW, Seftor REB, Seftor EA, Hess AR, Gruman LM, Kirschmann DA, et al. Effects of angiogenesis inhibitors on vascular network formation by human endothelial and melanoma cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1473–1477. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian AA, Burova OS, Stepanova EV, Baryshnikov AY. The involvement of apoptosis in melanoma vasculogenic mimicry. Melanoma Res. 2007;17:1–8. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3280112b76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian AA, Stepanova E, Grigorieva I, Solomko E, Baryshnikov A, Lichinitser M. VEGFR1 and PKCalpha signaling control melanoma vasculogenic mimicry in a VEGFR2 kinase-independent manner. Melanoma Res. 2011;21:91–98. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e328343a237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilimas T, Mascarenhas J, Palomero T, Mandal M, Buonamici S, Meng F, et al. Targeting the NF-κB signaling pathway in Notch-1 induced T-cell leukemia. Nat Med. 2007;13(1):70–77. doi: 10.1038/nm1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenblast E, Soto M, Gutierrez-Angel S, Hartl DA, Gable AL, Maceli AR, et al. A model of breast cancer heterogeneity reveals vascular mimicry as a driver of metastasis. Nature. 2015;520(7547):358–362. doi: 10.1038/nature14403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wander SA, Zhao D, Slingerland JM. P27: A barometer of signaling deregulation and potential predictor of response to targeted therapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(1):12–18. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JY, Sun T, Zhao XL, Zhang SW, Zhang DF, Gu Q, et al. Functional significance of VEGF-A in human ovarian carcinoma: role in vasculogenic mimicry. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:758–766. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.5.5765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Chadalavada K, Wilshire J, Kowalik U, Hovinga KE, Gever A, et al. Glioblastoma stem-like cells give rise to tumour endothelium. Nature. 2010;468:829–833. doi: 10.1038/nature09624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren BA, Shubik P. The growth of the blood supply to melanoma transplants in the hamster cheek pouch. Lab Invest. 1966;15:464–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L, Liu TT, Wang HH, Hong HM, Yu AL, Feng HP, et al. Hsp27 participates in the maintenance of breast cancer stem cells through regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and nuclear factor-kB. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13(5):R101. doi: 10.1186/bcr3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WK, Sung JJ, Lee CW, Yu J, Cho CH. Cyclooxygenase-2 in tumorigenesis of gastrointestinal cancers: an update on the molecular mechanisms. Cancer Lett. 2010;295:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Li Q, Li XY, Yang QY, Xu WW, Liu GL. Short-term anti-vascular endothelial growth factor treatment elicits vasculogenic mimicry formation of tumors to accelerate metastasis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2012;31:16. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-31-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Amann JM, Fukuda K, Takruchi S, Fujita N, Uehara H, et al. Akt kinase-interacting protein 1 signals through CREB to drive malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2015;75(19):4188–4197. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Sun B, Zhao X, Ma Y, Ji R, Gu Q, et al. Twist1 expression induced by sunitinib accelerates tumor cell vasculogenic mimicry by increasing the population of CD133+ cells in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2014;13(207):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Yu XH, Yan YG, Wang C, Wang WJ. PI3K/AKT signaling in osteosarcoma. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;444:182–192. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]