Abstract

Frequently fatal, primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) occurs in infancy resulting from homozygous mutations in natural killer (NK) and CD8 T cell cytolytic pathway genes. Secondary HLH presents after infancy and may be associated with heterozygous mutations in HLH genes. We report 2 unrelated teenagers with HLH and an identical heterozygous RAB27A mutation (c.259G>C). We explore the contribution of this Rab27A missense (p.A87P) mutation on NK cell cytolytic function by cloning it into a lentiviral expression vector prior to introduction into the human NK-92 cell line. NK cell degranulation (CD107a expression), target cell conjugation, and K562 target cell lysis was compared between mutant and wild-type transduced NK-92 cells. Polarization of granzyme B to the immunologic synapse and interaction of mutant Rab27A (p.A87P) with Munc13-4 were explored by confocal microscopy and proximity ligation assay, respectively. Over-expression of the RAB27A mutation had no effect on cell conjugate formation between the NK and target cells but decreased NK cell cytolytic activity and degranulation. Moreover, the mutant Rab27A protein decreased binding to Munc13-4 and delayed granzyme B polarization towards the immunologic synapse. This heterozygous RAB27A mutation blurs the genetic distinction between primary and secondary HLH by contributing to HLH via a partial dominant-negative effect.

Familial, or primary, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (fHLH) is an often fatal rare disorder of infancy resulting from dysregulation of the immune response (1). fHLH occurs in approximately one in 50,000 live births as it is frequently a result of homozygous mutations in autosomal recessive genes encoding proteins involved in lymphocyte cytolytic activity (e.g., Munc13-4, Rab27A, Perforin, Syntaxin 11, Munc18-2) (2) resulting in excessive immune activation or ineffective dampening of an immune response to infectious organisms (3, 4). Criteria to establish the diagnosis of fHLH are either known homozygous genetic mutations in fHLH genes or the presence of five of the eight of the following: fever; splenomegaly; cytopenias affecting at least two of three cell lines; hypertriglyceridemia and/or hypofibrinoginemia; hemophagocytosis in lymph nodes, bone marrow, or spleen; low or absent natural kill (NK) cell cytolytic activity; hyperferritinemia; and high levels of soluble CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor α-chain) (5). Following the diagnosis, most patients are treated with the etoposide-based HLH-2004 protocol. The predecessor of HLH-2004, the HLH-94 protocol and subsequent bone marrow transplantation, has been associated with a 45% mortality rate for primary and secondary forms of HLH (6).

Secondary forms of HLH (sHLH) frequently result from a reactive process to a number of infectious and oncologic conditions (5). When the same process occurs in the setting of rheumatic disease, it is termed macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) (7). fHLH criteria are often too restrictive for a timely diagnosis of sHLH or MAS. Attempts to develop disease-specific sHLH/MAS criteria have been proposed but these are limited to a few diseases (8). Most recently, propensity scores for all forms of sHLH and MAS have been proposed which are not disease-specific, but have yet to be validated (9).

Treatment for sHLH and MAS often vary widely from etoposide-based protocols to more traditional immunosuppressive approaches. Treatment of sHLH and MAS includes high dose corticosteroids (CS), intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and cyclosporine A (CsA) (7, 10). Recently, in uncontrolled reports, the recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (rIL-1Ra), anakinra, appears highly effective and well tolerated for rheumatic disease-associated MAS refractory to standard treatment (11–16). Mortality for sHLH and MAS treated by these approaches ranges from 0–14%; this is remarkably low despite the fact that many of these patients possess heterozygous mutations in fHLH genes which are also present in patients treated with the etoposide-based protocol (14, 17).

Of late, the genetics of sHLH and MAS have been more fully explored. Munc13-4 (UNC13D) gene polymorphisms (18) and a mutation (19), and perforin mutations (20), have all been associated with MAS in sJIA patients. Furthermore, a variety of heterozygous mutations in fHLH genes have been identified in a significant number of children (17, 21) and adults (22, 23) with sHLH and MAS. Moreover, over-expression in a NK cell line of a novel STXBP2 missense mutation from a patient with sHLH was recently demonstrated to decrease cytolytic capacity (17). Similarly, other heterozygous STXBP2 mutations in patients with sHLH were elegantly shown to act in a dominant-negative fashion to impair lytic granule fusion to the cell membrane with defective perforin-mediated cytolysis (24). Most recently, it has been reported that defective perforin-mediated cell lysis by NK cells and CD8 T cells results in prolonged interaction between the cytolytic cell and the antigen presenting targeting cell, and this contributes to a pro-inflammatory cytokine storm responsible for the clinical features associated with HLH (25). Thus, fHLH gene mutations in cytolytic pathway genes that disrupt or delay cytolysis, likely directly contribute to HLH pathology even in individuals with complete or partial dominant-negative heterozygous mutations.

Herein, we explore the effect of a heterozygous RAB27A missense mutation (c.259G>C) on NK cell cytolytic function. This variant is listed in the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database (dbSNP) as rs104894497 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/), and the minor allele frequency in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) database (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/) is 0.02% in a European population. This Rab27A p.A87P mutation was identified in 2 unrelated patients who developed sHLH later in life during their teenage years. Both patients responded well to immunosuppression with CS and CsA, with or without rIL-1Ra, avoiding the toxicity and morbidity associated with etoposide-based protocols. These disease-contributing single copy fHLH-associated gene mutations from sHLH patients blur the genetic distinction between fHLH and sHLH. Moreover, this suggests that a much larger proportion of the general population may be at risk for sHLH development if only one mutant copy can contribute to delayed cytolytic activity. Finally, despite the genetic contribution to sHLH and MAS shared with fHLH, these patients pose the question as to whether less toxic immunosuppression-based treatments may be preferred to etoposide-containing regimens as first line therapy for sHLH and MAS patients.

Materials and Methods

Patient data

Data pertaining to clinical course, laboratory values, and treatment was abstracted from the patients’ electronic medical records. The patients’ peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were sequenced for the following HLH genes: UNC13D, PRF1, STX11, STXBP2, and RAB27A. The RAB27A mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing as described (23) using DNA obtained from a buccal swab from the American patient and from both of her parents, and from peripheral blood of the Italian patient, his sibling, and both his parents. There was no family history of autoimmunity, autoinflammatory disease, or unexplained febrile deaths in the families, and no extended RAB27A genotyping was carried out beyond the patients, parents, and sibling.

DNA constructs

cDNAs encoding wild-type (WT) human Rab27A and Munc13-4 were generated by reverse transcription from RNA of the human NK-92 NK cell line (26). The cDNAs were cloned into expression vectors and the WT sequences were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The patient-derived RAB27A mutant cDNA (c.259G>C) was generated from the WT RAB27A cDNA by site-directed mutagenesis as described (27) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. The lentiviral expression vector, z-368-ΔNP, and the packaging plasmid, Δ8.91, were kindly provided by Dr. Philip Zoltick (The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia) (28). Both WT and mutant RAB27A cDNAs were independently subcloned into z-368-ΔNP to help generate recombinant lentiviruses. These viruses were separately transduced into NK-92 cells as detailed below. Transduction efficiencies were monitored by co-expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) as detected by flow cytometry (FCM). For protein-protein interaction assays, a FLAG-tag-fused UNC13D cDNA and hemagglutinin (HA)-tag-fused WT and mutant RAB27A cDNAs were subcloned into z-368-ΔNP by a 2A viral linker. Both the FLAG tag and HA markers were coupled to the 3′ ends (carboxy terminals) of the respective proteins and represented exogenous versions of Munc13-4 or Rab27A in the transduced NK-92 cells studied.

Antibodies and probes

The anti-human CD56-PE-Cy7 and CD107a-PE monoclonal antibodies (mAb) were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). The anti-human granzyme B-APC antibody was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA), and the rabbit antibody against green fluorescent protein (GFP) was from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). F-actin and granzyme B were also detected with phalloidin conjugated with Alexa Fluor™ 555 (Invitrogen) and anti-granzyme B conjugated to Alexa Fluor™ 647 (Invitrogen), respectively. The anti-FLAG rabbit antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA), and the anti-HA mouse mAb was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Fluorochrome tagged anti-perforin and anti-interferon-γ (IFNγ) were from BD Biosciences, and eBiosciences, respectively. For the in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA), the probes, anti-rabbit PLUS and anti-mouse MINUS, and the Texas Red-conjugated detection reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). For the Western blot assays, rabbit-anti-HA and chicken anti-FLAG antibodies were obtained from Abcam. The rabbit anti-β-actin and anti-Rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor™ 680 conjugated polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen, and the IRDye800CW donkey anti-chicken IgG was bought from LI-COR Biosciences (Lincoln, NB).

Lentiviral preparation and transduction

HEK293T cells were transfected with the respective z-368-ΔNP-expression constructs along with Δ8.91 and pVSV-G using the FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Roche, Branford, CT). Lentivial production was concentrated using the lenti-X concentrator reagent (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). NK-92 cells were infected with lentiviruses overnight at an MOI of 50:1. Transduction efficiency was between 45–55% at day 5 and afterward for up to 4 weeks. All assays were performed between 2–3 weeks following lentiviral infection.

Cytotoxicity and degranulation assays

The NK-sensitive K562 erythroleukemia target cells (29) were labeled by the cell tracer dye, eFluor450 (eBioscience), 12 hours prior to the cytotoxicity assay. The GFP-expressing, lentiviral-transduced NK-92 cells and labeled K562 target cells were mixed together at different effector to target (E:T) cell ratios and incubated at 37°C for 4 hours in the presence (24 hour pre-incubation) or absence of rIL-6 (10–50 ng/mL). The cells were then stained with live/dead near-IR dye (Invitrogen) and analyzed by FCM (LSRII, BD Biosciences). For cytotoxicity assays using patient and control frozen peripheral blood samples, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were thawed and cultured in RPMI media with10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT) and rIL-2 (50 U/mL) for 24 hours. Then, K562 cells were loaded with BATDA (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and mixed with Ficoll-separated PBMC at E:T ratios of 6:1 to 100:1 for 3 hours prior to measuring lysis by EuTDA fluorescence.

For degranulation assays, the transduced NK-92 cells were mixed with K562 cells at a 2:1 E:T ratio and incubated between 0 and 4 hours in the presence of fluorochrome-conjugated anti-CD107a antibody. K562 target cells served as a stimulus for NK-92 cell degranulation. To identify NK-92 effector cells, cells were either labeled with CFSE 12 hours prior to degranulation assays or stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-CD56 mAb after incubation with K562 stimulator cells. CD107a cell surface expression on NK-92 cells was detected by FCM as described by others (30). For degranulation assays involving patient and control frozen peripheral blood samples, PBMC were thawed and cultured as above, and Ficoll-separated PBMC were incubated with K562 cells for 3 hours at E:T ratios of 10:1 to 1:3 in the presence of anti-CD107a Ab. NK cells were identified with mAb against CD56 (NK cells) and CD3 (T cells gated out).

Intracellular perforin and IFNγ levels

PBMCs were isolated from the Italian patient and controls by Ficoll separation and then were frozen. Cells were thawed and cultured at a density of 1×106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, with or without hIL-6 (10 ng/ml) and soluble hIL-6 receptor (125 ng/ml). After 24 hours of incubation at 37°C in the presence or in the absence of IL-6/sIL-6R, IL-2 (50 U/ml) was added to the medium, and cells were incubated for another 24 hours. Intracellular perforin expression levels in the NK cell subset (CD56+CD3−) was evaluated by FCM as previously described (31). For intracellular detection of IFNγ, Rab27A (WT or mutant) transduced GFP+ NK-92 cells were incubated 1:1 with K562 cells for 4 hours prior to detection of intracellular IFNγ by FCM as described (31).

Cell-cell conjugation assays

The GFP-expressing lentiviral-transduced NK-92 cells were mixed with cell tracer dye (eFluor 450)-labeled K562 cells and centrifuged for 30 seconds at a very low speed. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 0, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, or 480 minutes and then fixed with a 1% paraformaldehyde solution. Conjugates between NK-92 cells and K562 cells were detected by two-color FCM and analyzed using Flow.jo 8.8.6 software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

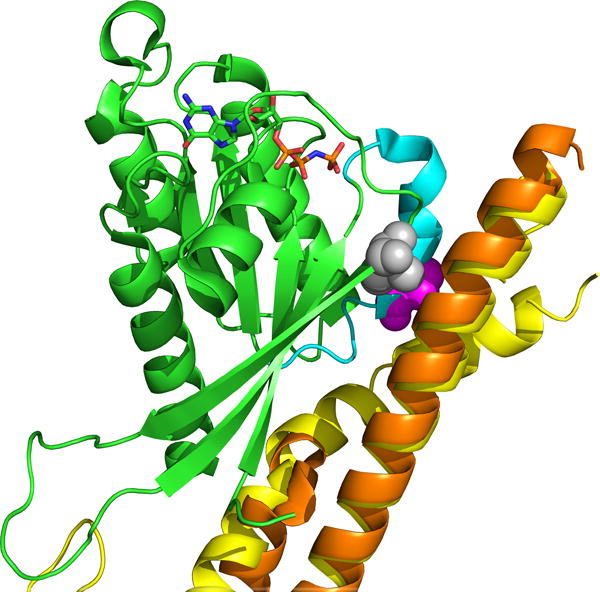

Structural modelling

Modeling and figure generation (Figure 4) of Rab27A p.A87P bound to WT Slp2-a and WT melanophilin was performed using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System software package (DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA) using prior published Rab27A WT structures (32, 33).

Figure 4. The Rab27A p.A87P mutation is located in a putative Rab27A/Munc13-4 binding site.

The crystal structure of Rab27A (green) is shown with Munc13-4 homologs, melanophilin (yellow) and Slp2-a (orange). The positions of Rab27A mutations p.A87P (purple) and p.I44T (gray), both of which disrupt binding to WT Munc13-4 in vitro, are shown.

Proximity ligation assay (PLA)

NK-92 cells were infected with a FLAG-tagged WT Munc13-4-expressing lentivirus, and transfected cells were sorted by co-expression of GFP. Cells were expanded in vitro and FLAG-tag expression was confirmed by intracellular staining and FCM. NK-92 cells were superinfected with a HA-tagged WT or mutant (p.A87P) Rab27A-expressing lentivirus. Exogenous Rab27A expression was confirmed by intracellular staining against the HA-tag. Proximity of the proteins, a surrogate of protein-protein interaction, was detected by the Duolink method as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich). Dual lentivirus-expressing NK-92 cells were mixed 1:1 with K562 cells for 30 minutes at 37°C to activate the cytolytic pathway. Cells were cytospun onto glass slides and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. Fixed cells were stained with polyclonal rabbit anti-FLAG (Munc13-4) antibodies and a mouse anti-HA (Rab27A) mAb for 1 hour prior to 2 washes. Cells were then incubated for 1 hour with anti-rabbit-PLA and anti-mouse-PLA containing complimentary proprietary PCR primers. Cells were washed twice and ligation solution was added for 30 minutes. Cells were washed again prior to addition of amplification solution for 100 minutes. Slides were sealed and images were taken with an Olympus BX41 camera. Single protein interactions were visualized using fluorescence and bright-field images, and the numbers of PLA particles per cell were counted and averaged for 100 cells per condition (blinded to the counter, M.Z.).

Co-immunoprecipitaton assays

WT Munc13-4-FLAG expressing NK-92 cells were sorted by GFP co-expression and superinfected with lentiviruses expressing empty vector control, WT Rab27A-HA, or mutant Rab27A p.A87P-HA. The transduced NK-92 cells were stimulated with K562 cells at a ratio of 1:1 for 0, 2, and 6 hours prior to cell lysis for immunoprecipitation. FLAG immunoprecipitation kits purchased from Sigma-Aldrich were used as per the manufacturer’s guidelines. For Western blots, cell lysates and immunoprecipitated proteins were electrophoresed on mini Protean-TGX gels from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) under denatured or native conditions. In the blotting process, rabbit-anti-HA and chick-anti-FLAG were used to detect HA- and FLAG-conjugated proteins, respectively, followed by anti-rabbit-IgG antibody conjugated with Alexa Flour 680 and donkey-anti-chicken-IgG conjugated with IRDye800CW. Use of an Odyssey Infrared Imager (LI-COR Biosciences) was kindly provided by Dr. John Mountz (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL) and used to scan the blotted signals on the PVDF (polyvinylidene fluoride) membranes. ImageJ2 software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was used to measure band intensity.

Confocal imaging assays

For immune synapse imaging assays, the lentiviral-transduced NK-92 cells were mixed with CFSE- (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) labeled K562 target cells and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were then spun down to a glass slide using a cytospin instrument and fixed using a 1% paraformaldehyde solution. Immune fluorescent staining of granzyme B and F-actin distributions within cells was accomplished with fluorochrome labeled anti-granzyme B mAb and phallotoxins (34), respectively. To enhance the imaging, Alexa Flour 488- (Life Technologies) labeled anti-GFP mAb was included for intracellular staining. For granzyme B polarization assays, NK-92 effector cells and K562 target cells were mixed at a 1:1 ratio and incubated for different time periods (0–8 hours) before fluorescent staining of granzyme B and cell nuclei (DAPI). Confocal imaging was performed and recorded using a laser scanning microscope with a digital camera (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Confocal imaging data were analyzed using the Bioquant system (Nashville, TN). Percent polarized cells (>75% granzyme B at the immunologic synapse) was calculated by counting 200 cells per time point, per condition in a blinded (time point and condition masked) fashion to the viewer (M.Z.).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 6 (La Jolla, CA) software. Two-way ANOVA analysis was used to calculate P values (α=.05) for the NK-92 cell cytotoxicity assay, the granzyme B polarization analyses, and the interaction between Munc13-4 and Rab27A as detected by the PLA.

Study approval

The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù, respectively. Written, informed consent for all study aspects, including publication of potentially identifiable material, was obtained from the patients and their respective parents.

RESULTS

Clinical histories

A previously healthy 18-year-old Caucasian American female was admitted to the hospital on the gastroenterology service for 2 weeks of fever and abdominal pain. On examination her liver and spleen were notably enlarged, she was hypertensive, and her mental status was decreased. Her laboratory findings were notable for pancytopenia (WBC - 1,720 cells/μL, hemoglobin −10.9 mg/dL, platelets - 44,000/μL), liver failure [albumin - 2.7 mg/dL (≥3.7), AST - 3,487 IU/L (≤30), ALT - 2,523 IU/L (≤35), aldolase - 61.8 U/L (<8.1), triglycerides - 201 mg/dL (≤140)], coagulopathy [PT - 20.7 seconds (≤15.2), PTT - 59.2 (≤36.0), D-dimers - 7,639 ng/mL (≤240), fibrinogen - 139 mg/dL (164–458)], and inflammation [C-reactive protein (CRP) - 5.96 mg/dL (<1.00), ferritin - 8,446 ng/ml (≤115), sCD25 - 4,171 units/mL (<1,105), sCD163 - 1,718 units/mL (<1,378)]. Her NK cell numbers were normal but NK cell function was virtually absent (2% lysis at the 50:1 E:T ratio). An extensive infectious work-up was unrevealing with notably negative or normal evaluations for hepatitis A/B/C, HIV-1, EBV, CMV, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, and enterovirus. Her ANA test was negative, but her serum complement levels were low [C3 - 20 mg/dL (51–95), C4 - 3 mg/dL (8–44)], a feature of MAS (35). The bone marrow biopsy specimen was essentially normal except that CD163 staining revealed increased numbers of activated macrophages. A brain MRI was normal. She satisfied criteria for HLH with 7 of 8 features (5 required) present (fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia, hypofibrinoginemia, decreased NK cell function, hyperferritinemia, elevated sCD25) (5).

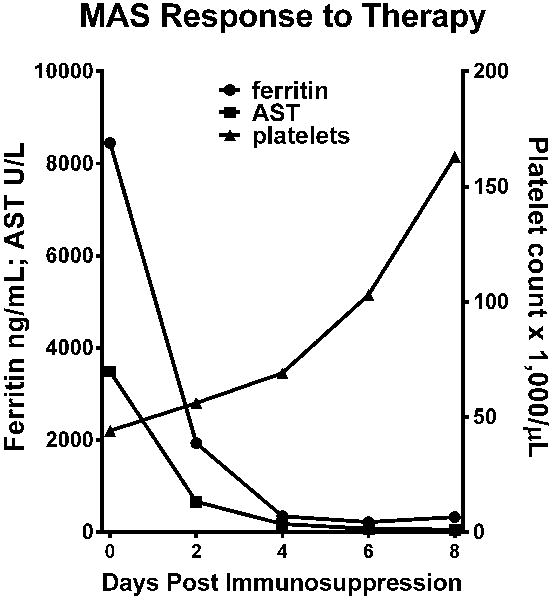

One week into the hospital admission, and just prior to transfer to intensive care for clinical decompensation, she was started on high dose intravenous methylprednisolone (500 mg twice daily for 5 days), CsA (3.5 mg/kg/day divided twice daily, intravenously), and subcutaneous anakinra (rIL-1Ra) at 100 mg (1.6 mg/kg) daily. Within 24 hours of immunosuppressive therapy, her clinical condition dramatically improved, and her laboratory features of sHLH showed marked improvement (Figure 1). She was discharged to home on prednisone 60 mg twice daily, CsA 200 mg twice daily, and anakinra 100 mg daily within 6 days of starting therapy. Within 2 weeks of leaving the hospital she developed a bilateral symptomatic chronic anterior uveitis that required periocular CS injections for control of inflammation. Three months after leaving the hospital she developed unilateral herpes simplex keratitis that responded to acyclovir therapy. Her daily oral CS had been tapered to off, and by 6 months she was also off of CsA, as both sHLH and uveitis were in remission. Anakinra was tapered to off within a year but she later developed HLA-B27-negative spondyloarthritis. She has had no further episodes of sHLH/MAS in the five years since her diagnosis.

Figure 1. Rapid clinical response of sHLH to immunosuppression with high dose CS, CsA, and anakinra.

Serum ferritin (circles) and AST (squares) levels, and circulating platelet counts (triangles) are graphed pre- (day 0) and post-immunosuppression (methylprednisolone, CsA, and anakinra/rIL-1Ra) for the American sHLH patient with the heterozygous Rab27A p.A87P missense mutation.

Her HLH gene testing was negative for coding mutations in UNC13D, PRF1, STX11, and STXBP2, but she was found to have a single copy missense mutation in RAB27A (c.259G>C) leading to an amino acid change (p.A87P). This particular mutation (dbSNP: 104894497) has been previously reported and is a known cause of Griscelli type 2, an established cause of fHLH when present as a compound heterozygous mutation (36). Since the DNA sample was obtained from peripheral blood, a buccal swab was analyzed for this mutation in the patient and both of her parents. The Rab27A p.A87P mutation was found to be germline in the patient and her father who has not had a known episode of sHLH.

Across the Atlantic Ocean, a previously healthy 15-year-old native Italian male (unrelated to the prior patient) was admitted to the hospital with a 4-week history of persistent fever (up to 39°C) unresponsive to antipyretics or broad-spectrum antibiotics, diarrhea, vomiting, skin rash, and arthritis. On physical examination he was noted to have a rash, hepatosplenomegaly, and swelling and tenderness of his elbows. Blood tests showed an increase in leukocyte count (16,210 cells/μL) with a normal platelet count (261,000 platelets/μL) and no evidence of anemia (12.7 g/dL), but signs of liver inflammation (AST - 224 IU/L, ALT - 635 IU/L, LDH - 676 IU/L) and systemic inflammation (D-dimers - 2.26 μg/mL, CRP - 33.23 mg/dL, ferritin - 5,896 ng/mL) with an elevated fibrinogen concentration (818 mg/dL). Lumbar puncture was negative, and viral and bacterial cultures were negative. Broad spectrum intravenous antibiotic treatment (ceftriaxone 100 mg/kg per day) was started with no effect on fever or clinical symptoms. Bone marrow biopsy showed increased numbers of activated macrophages, mostly expressing CD163, and pronounced hemophagocytosis. A diagnosis of sHLH was suspected (4 fHLH criteria met; sCD25 was not evaluated), and oral CsA (5 mg/kg/day) and intravenous pulse-dose methylprednisolone (1 gm/day for 3 days) were administered, followed by oral prednisone (2 mg/kg/day). However, his symptoms did not improve significantly. Laboratory tests showed a rapid rise in ferritin levels (25,770 ng/mL), hepatic enzyme activity (AST - 816 IU/L; ALT - 932 IU/L; γ-glutamyl transferase/GGT - 568 IU/L, LDH - 1,629 IU/L), with high fibrinogen (841 - mg/dL), and normal triglycerides (141 - mg/dL). He did not develop cytopenia, possibly because of the high doses of glucocorticoids. Weekly intravenous cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2 of BSA) and dexamethasone (10 mg/m2) were started. His fever disappeared within 48 hours after the first infusion and blood tests normalized after the third weekly infusion of cyclophosphamide. Intravenous cyclophosphamide was subsequently administered weekly for the first 5 weeks and afterwards monthly for 3 months. Dexamethasone was gradually tapered and discontinued after 4 months of treatment while CsA was discontinued after 2 years.

Three years after this first episode, and one year after discontinuation of CsA, the patient relapsed with fever, skin rash, arthralgia, and myalgia. Blood examinations revealed normal white blood cell and platelet counts, no evidence of anemia, mild liver impairment (AST - 33 IU/L, ALT - 78 IU/L, LDH - 451 IU/L), and inflammation (CRP - 13.26 mg/dL, ferritin - 5,481 ng/mL, fibrinogen - 707 mg/dL, D-dimer - 0.3 μg/mL). Bone marrow aspirate showed numerous activated macrophages and hemophagocytosis. Based on his clinical history, a relapse of sHLH was hypothesized, and high doses of oral dexamethasone (10 mg/m2) and oral CsA (4 mg/kg) were started with gradual clinical and laboratory improvement. Dexamethasone was gradually tapered and stopped after 8 months of treatment while continuing CsA. He has been free of disease for 3 years now. Genetic analysis was negative for mutations in PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, and STXBP2, but a single copy missense mutation in RAB27A (c.259G>C) was identified leading to the same amino acid change (p.A87P) found in the American patient. The Italian patient’s father carries the same mutation in Rab27A (p.A87P). Although the father is asymptomatic, he has a baseline moderately high serum ferritin level (800 ng/mL). These 2 unrelated teenage patients with sHLH prompted our investigation of the functional consequences of a single copy Rab27A missense mutation (p.A87P) on NK cell cytolytic function.

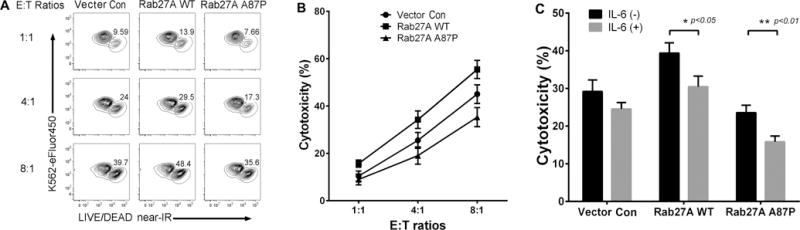

Rab27A p.A87P decreases NK cell cytolytic capacity

Since the American patient’s own NK cells had a defect in cytolysis, the contribution of her Rab27A p.A87P mutation to decreased cytolytic activity was explored. Using a lentiviral approach (see Methods), Rab27A WT or mutant Rab27A p.A87P was over-expressed in the human NK cell line, NK-92. Lentivirus-transduced NK-92 cells were sorted based on co-expression of GFP and mixed with fluorochrome-labeled K562 target cells at 3 different E:T cell ratios. Cell death was assessed by FCM using a proprietary dye that enters dead or dying cells. As seen in Figure 2A, cell death increased with increasing E:T ratios in all 3 conditions (empty vector control, Rab27A WT, and Rab27A p.A87P), but NK-92 cytolysis of K562 cells increased with over-expression of Rab27A WT, and decreased with over-expression of the patient mutation, Rab27A p.A87P. This effect was seen in repeated experiments (Figure 2B) and suggested that over-expression of Rab27A p.A87P was able to diminish NK cell cytolytic capacity. Since it has recently been shown that the inflammatory environment may also contribute to decreased NK cell function (31), the experiment was repeated in the presence or absence of exogenous rIL-6 (37). As seen in Figure 2C, addition of IL-6 further decreased NK cell cytotoxicity when either WT or mutant Rab27A p.A87P was over-expressed. These studies indicate that a single copy Rab27A p.A87P mutation may diminish NK cell function, and that in a pro-inflammatory environment this effect will be enhanced.

Figure 2. Rab27A p.A87P mutation decreases NK cell cytolytic function.

(A) eFluor450-labeled K562 target cells were mixed at increasing E:T ratios with NK-92 cells transduced with lentiviruses expressing empty vector control (left column), Rab27A WT (middle), or Rab27A p.A87P (right) and were incubated for 4 hours prior to FCM analysis of K562 cell death. FCM plots were gated on eFluor450+ cells with eFluor450 depicted on the Y-axis, and near-IR staining (dead cells) along the X-axis. One representative experiment is shown with percentages of lysed K562 cells enumerated. (B) A graph showing percent cytotoxicity at 3 different E:T ratios for lentivirus-transduced NK-92 cells [empty vector control (circles), Rab27A WT (squares), and Rab27A p.A87P mutation (triangle)]. Results are plotted as means ± SEM for 5 independent experiments. Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed statistically significant differences (p<0.05) among empty vector, the Rab27A WT-, and Rab27A p.A87P mutant-transduced NK-92 cells at all 3 E:T cell ratios. (C) K562 cytotoxicity (means ± SEM) from empty vector, WT, or Rab27A p.A87P mutant lentiviral transduced NK-92 cells in the presence or absence of exogenous IL-6 are shown for a 4:1 E:T ratio. IL-6 significantly decreased cytotoxicity of Rab27A WT (* p=0.0175) and p.A87P mutant (** p=0.0058) transduced cells (n=3).

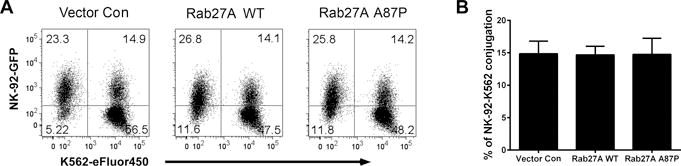

FCM was next used to explore whether decreased NK cell function was a result of a diminished ability of Rab27A p.A87P expressing NK cells to form conjugates with the K562 target cells. Lentivirus-transduced NK-92 cells were detected by GFP expression, and K562 target cells were labeled with the eFluor450 fluorochrome. As seen in Figure 3A, the percentage of conjugates (those cell pairs expressing both GFP and eFluor450, located in the upper right hand FCM quadrant) were virtually identical when the NK-92 cells were over-expressing Rab27A WT, Rab27A p.A87P, or the empty vector control at 30 minutes post incubation. This was seen repeatedly (p>0.5) (Figure 3B). Thus, the Rab27A p.A87P patient mutation had no obvious effect on NK cell to target cell conjugate formation at 30 minutes as assessed by FCM.

Figure 3. Rab27A p.A87P mutation does not alter NK cell conjugate formation with target cells.

NK-92 cells transduced with lentiviruses co-expressing GFP and empty vector control (left), Rab27A WT (middle), or Rab27A p.A87P (right) were mixed with eFluor450-labeled K562 cells and assayed for cell-to-cell conjugation at 30 minutes as assessed by FCM. (A) GFP expression (NK-92 cells) is shown along the Y-axis and eFluor450 fluoresence (K562 cells) along the X-axis. NK-92-K562 cell conjugates are noted in the upper right quadrants, and percentages of cells in each quadrant are noted. (B) The results shown are representative of 3 similar experiments, and the means ± SEM for percent conjugates are shown in the bar graph to the right.

Rab27A p.A87P partially disrupts interaction with WT Munc13-4

It had previously been reported that the Rab27A p.A87P mutation completely disrupted the ability of Rab27A to bind Munc13-4 in vitro as evaluated in a mammalian 2-hybrid assay (36). We next analyzed in silico the predicted crystal structure of Rab27A p.A87P interactions with Munc13-4 homologs, melanophilin and Slp2-a. The Rab27A p.A87P mutation is located within the switch 2 region of Rab27A (WT sequence is identical to Rab27B here) (Figure 4). Structural studies on related Rab27B/melanophilin (33) and Rab27A/Slp2-a (32) complexes confirm this switch 2 region of Rab27A as a binding site with Munc13-4. This is confirmed by biochemical analyses which demonstrate disruption of binding to WT Munc13-4 by mutants Rab27A p.A87P (switch 2 mutation) (36) and Rab27A p.I44T (located adjacent to switch 2 on switch 1) (38). Modeling of both the Rab27A p.I44T mutant (gray) and the patients’ p.A87P mutation (purple) predict disruption of binding to the Munc13-4 homologs, melanophilin (yellow) and Slp2-a (orange) (Figure 4).

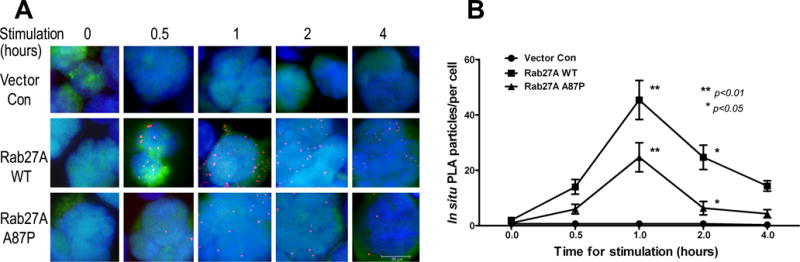

In order to test the ability of Rab27A p.A87P to quantitatively bind WT Munc13-4 in situ, we explored this interaction on a per cell basis using the PLA as detailed in the Methods. In brief, NK-92 cells were transduced with a lentivirus expressing a FLAG-tagged version of Munc13-4 WT and co-expressing GFP. GFP sorted NK-92 cells were super-infected with a lentivirus-expressing HA-tagged Rab27A WT, Rab27A p.A87P, or empty vector control. Expression levels were stable over several weeks in culture and roughly equivalent in all conditions (Supplemental Figure 1). The dually-transduced NK-92 cells were incubated with K562 target cells to activate the cytolytic pathway, and the cells were spun down onto glass slides and paraformaldehyde fixed. The fixed cells were incubated with a rabbit anti-FLAG antisera and a mouse anti-HA mAb. After washes, the cells were incubated with anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies, each conjugated with complimentary proprietary PCR primers. In situ, NK-92 cells were treated with ligation solution followed by PCR amplification solution containing fluorochrome-tagged DNA complimentary to the ligated primers as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Intracellular single protein-protein (Rab27A to Munc13-4) interactions were visualized as fluorescent particles and counted using fluorescence microscopy (Figure 5A). As no HA-tag was present in the empty vector control, there were no particles detected as to be expected. Interestingly, over the 4 hour time course the NK-92 cells transduced with HA-tagged Rab27A p.A87P demonstrated approximately half as many protein-protein interactions with FLAG-tagged Munc13-4 WT as did the NK-92 cells transduced with HA-tagged Rab27A WT (Figure 5B). This suggests the Rab27A p.A87P mutation partially disrupts the ability to interact in close proximity with Munc13-4 WT. This was supported by Western blot studies which revealed decreased co-immunoprecipitation of Rab27A p.A87P (compared to WT Rab27A) with WT Munc13-4 using lysates from transduced NK-92 cells (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 5. Rab27A p.A87P mutation results in decreased interaction with Munc13-4 WT protein.

(A) NK-92 cells were transduced with a lentivirus expressing FLAG-tagged Munc13-4 WT followed by superinfection with lentiviruses expressing nothing (top row), or HA-tagged Rab27A WT (middle) or Rab27A p.A87P mutant (bottom). The transduced NK-92 cells were stimulated with K562 cells for the indicated time periods prior to in situ PLA as described in the Methods. Particles representing protein-protein interactions specifically between transduced Munc13-4 and Rab27A are noted in orange. (B) Results from 3 independent experiments are summarized and plotted as in situ PLA particles per cell (means ± SEM) along the Y-axis and time of stimulation along the X-axis. Two-way ANOVA analysis showed statistically significant differences (p<0.05) between the means at the 1 and 2 hour time points for the Rab27A WT- and Rab27A p.A87P-transduced cells.

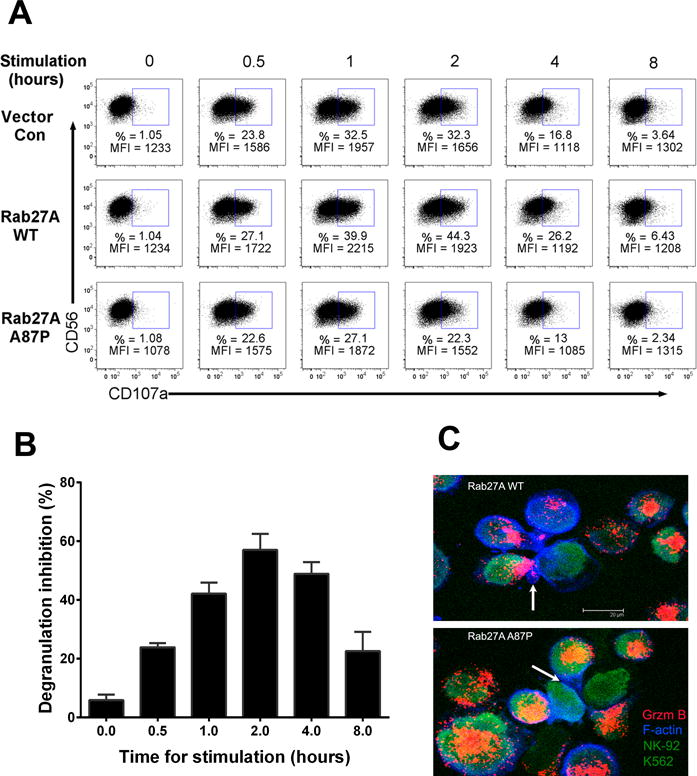

Rab27A p.A87P delays granzyme B polarization to the immunologic synapse

As Rab27A and Munc13-4 normally function to help transport granzyme B containing granules to the NK cell immunologic synapse, the degranulation ability of NK-92 cells transduced with Rab27A p.A87P was explored by examining CD107a cell surface expression. FCM measurement of cell surface CD107a on NK cells is a simple, quick, and reliable method to measure NK cell degranulation (30). NK-92 cells were transduced with a lentivirus expressing Rab27A WT, Rab27A p.A87P, or empty vector control. The cells were next incubated with K562 cells to stimulate cytotoxic granule degranulation as assessed over time by FCM using fluorochrome-conjugated anti-CD107a mAb. As predicted, at the zero hour time point, there is virtually no detectable CD107a expression (1%) on the cell surface of NK-92 cells separately transduced with the 3 different lentiviruses (Figure 6A). However, by 2 hours post-incubation with K562 cells, CD107a cell surface expression peaked (32%). Over-expression of Rab27A WT augmented degranulation compared to administered empty vector control at all the time points analyzed (44% at 2 hours), whereas Rab27A p.A87P inhibited CD107a expression in comparison to empty vector for the entire 8 hour time course (22% at 2 hours) (Figure 6A, B). This implies Rab27A p.A87P inhibits NK cell cytolytic function by disrupting cytolytic granule polarization to the immunologic synapse with the target cell.

Figure 6. Rab27A p.A87P mutation decreases NK cell degranulation and alters cytolytic granule polarization to the immunologic synapse.

(A) NK-92 cells transduced with lentiviruses expressing empty vector control (top row), Rab27A WT (middle), or Rab27A p.A87P (bottom) were mixed with K562 cells for the indicated times, and cell surface CD107a expression was detected by FCM. One representative set of results from 3 independent experiments is shown and gated on CD56+ NK-92 cells with CD56 expression depicted along the Y-axis and CD107a along the X-axis. Percentages (%) of CD107a+ cells and CD107a mean fluorescent intensities (MFI) are noted. (B) Percent decreased degranulation was calculated by the formula: 100% × (CD107a positive% × MFI from Rab27A WT transduced NK-92 minus CD107a positive% × MFI from Rab27A p.A87P transduced NK-92)/CD107a positive% × MFI from Rab27A WT transduced NK-92. The bar graph shows the means ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. (C) NK-92 cells transduced with lentiviruses expressing Rab27A WT (top panel) or Rab27A p.A87P (bottom panel) were incubated with CFSE-labeled K562 target cells. Confocal microscopy portrays granzyme B (present only in NK-92 cells) as pink to orange in color, F-actin as blue, and both NK-92 and K562 cells as green. The arrow in the top panel denotes NK-92 cell granzyme B polarization to the immunologic synapse formed with the K562 target cell, whereas the arrow in the lower panel points out a NK-92 cell bound to a K562 cell but lacking granzyme B polarization to the immunologic synapse.

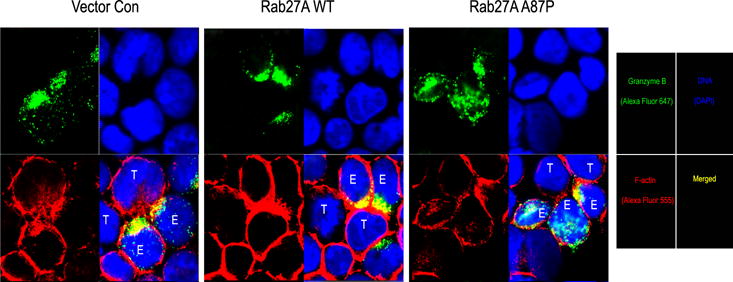

Granzyme B is an effector molecule in CD8 T cell and NK cell cytolytic granules that contributes to target cell apoptosis when delivered via a perforin (also contained in cytolytic granules) pore formed at the immunologic synapse between the lytic cell and the target cell (15, 39). The effect of Rab27A p.A87P on granzyme B polarization to the NK cell immunologic synapse was therefore explored using confocal fluorescence microscopy. GFP and Rab27A dual-expressing lentivirus-transduced NK-92 cells were incubated 1:1 with CFSE-labeled K562 target cells at 37°C for 30 minutes prior to being spun down onto glass slides and fixed and permeabilized with paraformaldehyde. Cells were then visualized with confocal microscopy (Figure 6C). In addition to the green GFP (NK-92 cells) and the green nuclear CFSE (K562 cells) stains, both cell types were identified by the addition of phallotoxins (blue) to highlight cytoplasmic actin. Granzyme B (orange to pink) was detected by the addition of fluorochrome-conjugated anti-granzyme B mAb. NK-92 cells transduced with the Rab27A WT lentivirus demonstrated granzyme B polarization to the immunologic synapse with the K562 target cell (Figure 6C, top panel, arrow), whereas Rab27A p.A87P mutant-expressing NK-92 cells did not appear to polarize granzyme B to the synapse formed with the K562 cell (Figure 6C, bottom panel, arrow). We further refined the immunologic synapse by defining the plasma membranes of the transduced NK-92 effector (E) cells and the K562 target (T) cells using directly conjugated and fluorochome-tagged phalloidin to detect F-actin (Figure 7). The control (Con) transduced NK-92 cells (E) clearly demonstrated granzyme B polarization to the immunologic synapses with adjoining K562 targets (T), and this appeared augmented when WT Rab27A was over-expressed, and notably diminished when mutant Rab27A p.A87P was transduced (Figure 7). As this was a single snapshot in time, granzyme B polarization to the immunologic synapse with K562 target cells was further explored by a time course analysis.

Figure 7. Polarization of granzyme B occurs at the plasma membrane of the immunologic synapse between NK-92 effector cells and K562 target cells but is decreased in those expressing mutant Rab27A p.A87P.

NK-92 cells effector cells (E) transduced with lentiviruses expressing empty vector control (left), Rab27A WT (middle), or mutant Rab27A p.A87P (right) were mixed with K562 cells target cells (T) and assayed for granzyme B polarization to the plasma membrane at the immunological synapse by confocal microscopy. granzyme B is noted in green (top left panels), DNA (DAPI nuclear stain) in blue (upper right panels), and F-actin cytoskeleton (defining cell membranes) in red (lower left panels). Merged images of granzyme B, DNA, and F-actin are presented in the bottom right panels with yellow representing granzyme B and F-actin overlap, and light blue depicting granzyme B not polarized to the cell membrane immunological synapse.

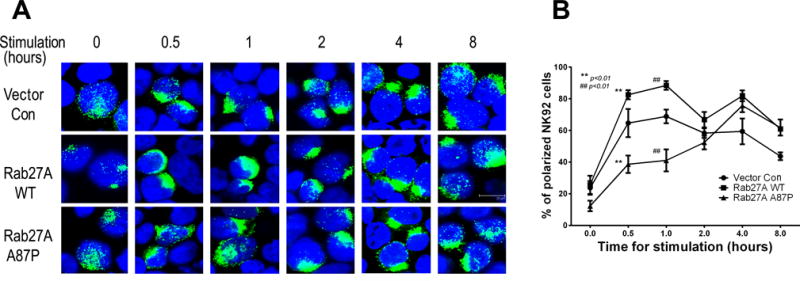

Rab27A-expressing lentivirus-transduced NK-92 cells were incubated 2:1 with K562 target cells for variable time periods, spun down to slides, and fixed as in Figure 6. Nuclei from both cell types were identified by DAPI (blue) staining, and granzyme B, present only in the NK-92 cells, was detected with fluorochrome (green)-tagged anti-granzyme B mAb (Figure 8A). Two-hundred cells per condition, per time point were counted (assessor blinded to time point and condition), and percentages of polarized cells (see Methods) were calculated over several experiments and graphed over a time course (Figure 8B). Cells overexpressing Rab27A WT polarized granzyme B at a higher rate over the first hour compared to empty vector control-transduced NK-92 cells. In contrast, NK-92 cells transduced with a lentivirus expressing Rab27A p.A87P displayed delayed kinetics of polarization, not reaching control values for 2–4 hours. To our knowledge, this is the first such demonstration of a heterozygous HLH gene mutation significantly delaying cytolytic vesicle polarization to the immunologic synapse. Thus, the patients’ mutant Rab27A protein acted in a partial dominant-negative fashion to delay granzyme B delivery to the immunologic synapse leading to decreased NK cell lytic function. It is likely that this delay in cytotoxic granule polarization results in decreased target cell lysis, prolonged engagement between the lytic and target cells, and increased pro-inflammatory cross talk between the lymphocyte (CD8 T cell or NK cell) and the antigen presenting cell in vivo (25). Supportive of this, evaluation of intracellular cytokine levels revealed statistically significant increased IFNγ expression in the mutant Rab27A p.A87P- versus WT Rab27A-transduced NK-92 cells incubated with K562 target cells for 4–8 hours (Figure 9).

Figure 8. Rab27A p.A87P mutation delays granzyme B polarization to the immunologic synapse.

(A) Vector control (top row), Rab27A WT (middle), and Rab27A p.A87P mutant (bottom) transduced NK-92 cells were stimulated with K562 cells for the indicated time periods prior to intracellular analysis of granzyme B polarization as assessed by confocal microscopy. One representative experiment is shown, where green represents granzyme B staining and blue denotes cell nuclei (DAPI stain). (B) Three independent experiments are summarized and plotted as percentages (Y-axis) of granzyme B polarized NK-92 cells (means ± SEM) versus time (X-axis) for vector control (circles), Rab27A WT (squares), and Rab27A p.A87P (triangles) expressing lentivirus-transduced cells. Statistically significant differences (p<0.0001) in the means of granzyme B-polarized cells between the Rab27A WT- and Rab27A A87-expressing NK-92 cells was noted by two-way ANOVA analysis for the 0.5 and 1.0 hour time points.

Figure 9. Increased IFNγ expression by mutant Rab27A p.A87P, compared to WT Rab27A, expressing NK-92 cells following incubation K562 target cells.

(A) Empty vector (CTL), mutant Rab27A p.A87P, or WT Rab27A lentiviral transduced NK-92 cells were incubated with K562 cells for 4 hours, and intracellular IFNγ levels of GFP+ NK-92 cells are plotted (X-axis) versus side scatter (Y-axis) for one representative experiment. (B) Average IFNγ levels (means ± SEM) are plotted for 3 similar experiments.

Rab27A p.A87P inhibits cytolytic function of unmanipulated patient derived NK cells

In order to explore the effect of the Rab27A p.A87P mutation on the sHLH patients’ own naturally occurring NK cells during a state of health, PBMC were isolated from the Italian patient’s peripheral blood, along with blood from his father (Rab27A p.A87P heterozygote), mother (Rab27A WT), sister (Rab27A WT), and 3 unrelated healthy adult controls. PBMC were incubated with K562 target cells, and NK cells (CD56+, CD3−) were analyzed for degranulation (CD107a expression) at varying E:T ratios. With increasing stimulus from K562 target cells (decreasing E:T ratios), there was a trend for increased degranulation of NK cells (Figure 10A). Notably, the percentage of NK cells from both the Italian patient and his father (both heterozygous for Rab27A p.A87P) capable of degranulation was significantly decreased compared to NK cells from the patient’s mother and sister (both WT Rab27A). Thus, NK cell function was decreased in unmanipulated heterozygous Rab27A p.A87P NK cells from peripheral blood, even during a state of good health.

Figure 10. Heterozygous Rab27A p.A87P patient NK cells have decreased degranulation and cytotoxicity.

(A) PBMC were obtained from the heterozygous Rab27A p.A87P sHLH Italian patient (black bar), his Rab27 p.A87P heterozygous father (checkered bar), his Rab27A WT mother (gray bar), and his Rab27A WT sister (white bar). PBMC were mixed with K562 cells at various E:T ratios as in the Methods. Percentages of NK cells undergoing degranulation (CD107+, CD56+, CD3−) were determined by FCM. (B) PBMC were obtained from the heterozygous Rab27A p.A87P sHLH Italian patient (at 2 time points over a 24-month period of disease inactivity; black bar), his Rab27A p.A87P heterozygous father (single time point; checkered bar), and from 3 normal healthy unrelated control individuals (white bar). Cell lysis of NK-sensitive K562 cells was analyzed at various E:T ratios as detailed in the Methods. Error bars represent means ± SEM for the patient (2 time points) and the average of the 3 controls.

Similarly, heterozygous Rab27A p.A87P NK cells from both the Italian sHLH patient and his father demonstrated significantly reduced NK cell lytic activity versus K562 target cells in comparison to NK cells from healthy adult controls (Figure 10B). NK cell lytic activity was approximately 50% reduced for Rab27A p.A87P expressing NK cells at all E:T ratios studied. Again, the sHLH patient’s NK cells were analyzed at time of good health (2 separate time points averaged) demonstrating decreased NK cell lytic activity at baseline. In general, there was no substantial difference in intracellular perforin levels in NK cells from the patient and his father in comparison to a healthy control and the patient’s mother and sister (Supplemental Figure 3). However, addition of IL-6 notably lowered perforin levels in those with and without the Rab27A p.A87P mutation, consistent with decreased cytolytic activity of the NK-92 cells incubated with IL-6 (Figure 2C), as well as a recent publication (31). Thus, it is likely that the Rab27A p.A87P contributes to decreased NK cell function and subsequent sHLH clinical expression. However, the mutation alone is not sufficient to cause sHLH as the patient’s father expresses the same mutation resulting in decreased NK cell function but no clinically overt sHLH, which may require an inflammatory milieu. Similarly, the Italian Rab27A p.A87P sHLH patient is not chronically ill with sHLH despite baseline decreased NK cell function.

Discussion

fHLH and sHLH or MAS likely represent the same disorder along a spectrum of hyperinflammation and genetics (17, 40). Historically, those patients presenting early in life with homozygous and compound heterozygous mutations of HLH-causing genes have been classified as having fHLH, even if the inflammatory cascade initiation was secondary to a known infectious cause. Those lacking family history or known genetic mutations were previously classified as having acquired, reactive, or sHLH (41). However, recent reports have detailed many later-onset sHLH and MAS patients found to have heterozygous mutations of the same fHLH causing genes (17–20, 22–24, 42–44), although without any supporting functional or mechanistic analyses of the effects of these heterozygous mutants, except for a few studies (17, 24, 42).

Mutations in HLH genes among sHLH and MAS patients are not likely coincidental, in part based on their relatively high frequency among these cohorts compared to the background population (17, 23, 45), but also because of their ability to act in a hypomorphic or partially dominant-negative fashion on NK cell cytolytic capacity (Figure 2A, B) (17). Moreover, decreased lytic activity in the presence of IL-6 (Figure 2C) may synergize with heterozygous partial dominant-negative, or hypomorphic, fHLH gene mutations to lead to clinical sHLH. Consistent with these findings, excess IL-6 (in vivo and in vitro) has been observed to decrease NK cell activity with decreased granzyme B and perforin expression in murine and human NK cells (31). This may be particularly relevant to MAS in the setting of sJIA where IL-6 is often elevated, and heterozygous fHLH gene mutations are frequently present in those with MAS (15). Nevertheless, one cannot formally rule-out the possibility of not identifying other contributory genes leading to decreased NK cell function, or not identifying causative mutations or deletions in non-coding portions of HLH genes among sHLH and MAS patients (46). However, the fact that isolated over-expression of the Rab27A p.A87P mutation in a NK-92 cell possessing the Rab27A WT gene is able to delay granzyme B polarization to the immunologic synapse (Figure 8) and decrease NK cell lytic function (Figure 2) argues these genes may directly contribute to HLH pathophysiology as single copy mutations. Analogous decreased NK cell function has recently been reported for over-expression of a novel Munc18-2 mutation associated with a fatal case of sHLH in a teenager (17). Thus, single copy mutations in fHLH genes (identified in sHLH patients) introduced into NK cells can act in a partially dominant-negative fashion to disrupt NK cell function and likely directly contribute to sHLH or MAS pathology under certain inflammatory states (e.g., particular viral infections, lymphoma, autoimmune or autoinflammatory disease flares) (47).

Herein, we explore the mechanism for the heterozygous Rab27A p.A87P mutation contributing to sHLH in 2 unrelated individuals. The decreased lytic activity of NK cells expressing Rab27A p.A87P likely results from the mutation disrupting interaction with its binding partner, Munc13-4 (Figures 4 and 5, and Supplemental Figure 2). The Rab27A p.A87P mutation resides along the highly conserved Rab protein switch 2 region, critical for interaction with Munc13-4 and its homologs in other tissues (Figure 4). The decreased interaction of Rab27A p.A87P with WT Munc13-4 (Figure 5 and Supplemental Figure 2) likely occurs via a partial dominant-negative effect leading to inhibition of cytolytic granule exocytosis, since the Rab27A p.A87P mutant probably effectively competes with WT Rab27A for other binding partners in the exocytosis pathway. Similarly, a Rab27A p.G78L mutation, which also resides along the switch 2 region, was shown to inhibit lymphocyte cytotoxic granules exocytosis via a dominant-negative effect (48). The decreased interaction of Rab27 p.A87P with Munc13-4 results in a delay of NK cell cytolytic granule polarization to the immunologic synapse (Figure 8). The delay in polarization occurs as early as 30 minutes post-interaction with the K562 target cells (Figure 7B) but without disrupting the interaction of the NK cells with the target cells (Figure 3), including several hours post-incubation (Supplemental Figure 4).

Recently, it has been shown that NK cells or cytotoxic CD8 T cells homozygous deficient in either granzyme B or perforin delay separation from their target cells with an approximately 5-fold longer interaction at the immunologic synapse (25). Interestingly, the absence of cell lysis prevents the disengagement of the cells as this occurs via a caspase dependent mechanism from the dying target cell (25). This prolonged interaction of the lytic cell and the target cell results in hypersecretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF, IFNγ) and thus provides a link between failed perforin-mediated cytolytic activity and the cytokine storm responsible for clinical HLH (25). Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that a mutation (Rab27A p.A87P) that delays cytolytic granule polarization to the plasma membrane of the immunologic synapse (Figures 7 and 8) and decreases target cell death (Figures 2 and 10) likely leads to prolonged interaction of cytolytic lymphocytes with antigen presenting cells resulting in a pro-inflammatory cytokine storm (Figure 9) responsible for clinical manifestations of sHLH.

The distinction between sHLH/MAS and fHLH currently determines treatment decisions. Patients diagnosed with fHLH have typically been treated with cytotoxic agents, namely etoposide, and hematopoetic stem cell transplant (5), with a 5-year survival for both fHLH and sHLH/MAS patients of only 55%. By contrast, some patients with MAS and its variants have been treated by targeting the hyperinflammatory state acutely with high dose CS, CsA, and IL-1 blockade (Figure 1) (14), including effective IL-1 blockade in sepsis patients with features of MAS (49). This treatment approach has yet to be evaluated in a large prospective MAS cohort, but uncontrolled studies report short term survival exceeds 85%; long-term survival data are not yet currently available (14, 17). The patients reported herein have been clinically stable for three and five years, respectively, after their initial MAS presentations and have received minimal to no immunosuppression for the last 3 years. Nonetheless, the place of hematopoetic stem cell transplantation in this group of patients with heterozygous mutations in HLH-associated genes remains unclear. These patients are theoretically at risk of developing recurrent MAS under certain hyperinflammatory states (e.g., certain viral infections). However, a relatively rapid and apparently sustained response to a limited course of immunosuppression without the use of cytotoxic agents suggests transplantation may be unnecessary in many sHLH and MAS patients, even in the face of heterozygosity of known disease-causing mutations. Further follow-up of patients with sHLH and MAS who respond to immunosuppressive therapy alone is needed to determine the rate of recurrence of sHLH and MAS and the subsequent response to therapy.

In conclusion, we identified a heterozygous RAB27A known Griscelli-2 missense mutation (c.259G>C) in two previously healthy unrelated teenagers who each presented with sHLH. Over-expression of this single copy HLH gene mutation in a human NK cell line resulted in decreased degranulation, diminished interaction with its Munc13-4 binding partner, delayed polarization of granzyme B to the immunologic synapse, increased IFNγ expression, and reduced cytolytic function. Decreased NK cell lytic activity was noted in naturally occurring (patient derived) heterozygous Rab27A p.A87P NK cells at baseline arguing for the requirement of an additional trigger(s) to result in clinically evident sHLH. When sHLH was clinically severe, both Rab27A p.A87P heterozygous patients responded to immunosuppression and have not required traditional etoposide-based treatment or bone marrow transplantation up to 5 years after initial presentation. Thus, the identification of partially dominant-negative single copy gene mutations in late-onset sHLH blurs the genetic distinction between fHLH and sHLH, underscores the increased prevalence of sHLH and MAS compared to fHLH, and poses an additional consideration in the choosing of the safest effective therapy for sHLH and MAS patients with or without heterozygous HLH gene mutations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their parents and sibling for participation in this research.

Footnotes

This research was supported by grants from the Kaul Pediatric Research Institute (to R.Q.C.) and the NIH (R01 AR059049 to A.A.G.; R01 AI097629 and R01 AI049342 to M.R.W.), and use of the UAB Immunology FCM core facility (P30 AR048311).

References

- 1.Janka GE. Familial and acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:233–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-041610-134208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman HR, Ramanan AV. Review of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:688–693. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.176610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behrens EM. Macrophage activation syndrome in rheumatic disease: what is the role of the antigen presenting cell? Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7:305–308. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisman DN. Hemophagocytic syndromes and infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:601–608. doi: 10.3201/eid0606.000608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski J, Janka G. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124–131. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henter JI, Samuelsson-Horne A, Arico M, Egeler RM, Elinder G, Filipovich AH, Gadner H, Imashuku S, Komp D, Ladisch S, Webb D, Janka G. Treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with HLH-94 immunochemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002;100:2367–2373. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deane S, Selmi C, Teuber SS, Gershwin ME. Macrophage activation syndrome in autoimmune disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;153:109–120. doi: 10.1159/000312628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cron RQ, Davi S, Minoia F, Ravelli A. Clinical features and correct diagnosis of macrophage activation syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015;11:1043–1053. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2015.1058159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, Marzac C, Aumont C, Chahwan D, Coppo P, Hejblum G. Development and validation of a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome (HScore) Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2613–2620. doi: 10.1002/art.38690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ringold S, Weiss PF, Beukelman T, DeWitt EM, Ilowite NT, Kimura Y, Laxer RM, Lovell DJ, Nigrovic PA, Robinson AB, Vehe RK. 2013 update of the 2011 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: recommendations for the medical therapy of children with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and tuberculosis screening among children receiving biologic medications. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2499–2512. doi: 10.1002/art.38092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruck N, Suttorp M, Kabus M, Heubner G, Gahr M, Pessler F. Rapid and sustained remission of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated macrophage activation syndrome through treatment with anakinra and corticosteroids. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:23–27. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318205092d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahn PJ, Cron RQ. Higher-dose Anakinra is effective in a case of medically refractory macrophage activation syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:743–744. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly A, Ramanan AV. A case of macrophage activation syndrome successfully treated with anakinra. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:615–620. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miettunen PM, Narendran A, Jayanthan A, Behrens EM, Cron RQ. Successful treatment of severe paediatric rheumatic disease-associated macrophage activation syndrome with interleukin-1 inhibition following conventional immunosuppressive therapy: case series with 12 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:417–419. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravelli A, Grom AA, Behrens EM, Cron RQ. Macrophage activation syndrome as part of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: diagnosis, genetics, pathophysiology and treatment. Genes Immun. 2012;13:289–298. doi: 10.1038/gene.2012.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Record JL, Beukelman T, Cron RQ. Combination therapy of abatacept and anakinra in children with refractory systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a retrospective case series. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:180–181. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang M, Behrens EM, Atkinson TP, Shakoory B, Grom AA, Cron RQ. Genetic defects in cytolysis in macrophage activation syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16:439–446. doi: 10.1007/s11926-014-0439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang K, Biroschak J, Glass DN, Thompson SD, Finkel T, Passo MH, Binstadt BA, Filipovich A, Grom AA. Macrophage activation syndrome in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis is associated with MUNC13-4 polymorphisms. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2892–2896. doi: 10.1002/art.23734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazen MM, Woodward AL, Hofmann I, Degar BA, Grom A, Filipovich AH, Binstadt BA. Mutations of the hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-associated gene UNC13D in a patient with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:567–570. doi: 10.1002/art.23199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vastert SJ, van Wijk R, D’Urbano LE, de Vooght KM, de Jager W, Ravelli A, Magni-Manzoni S, Insalaco A, Cortis E, van Solinge WW, Prakken BJ, Wulffraat NM, de Benedetti F, Kuis W. Mutations in the perforin gene can be linked to macrophage activation syndrome in patients with systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:441–449. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhizhuo H, Junmei X, Yuelin S, Qiang Q, Chunyan L, Zhengde X, Kunling S. Screening the PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, SH2D1A, XIAP, and ITK gene mutations in Chinese children with Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;58:410–414. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sieni E, Cetica V, Piccin A, Gherlinzoni F, Sasso FC, Rabusin M, Attard L, Bosi A, Pende D, Moretta L, Arico M. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis may present during adulthood: clinical and genetic features of a small series. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang K, Jordan MB, Marsh RA, Johnson JA, Kissell D, Meller J, Villanueva J, Risma KA, Wei Q, Klein PS, Filipovich AH. Hypomorphic mutations in PRF1, MUNC13-4, and STXBP2 are associated with adult-onset familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2011;118:5794–5798. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-370148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spessott WA, Sanmillan ML, McCormick ME, Patel N, Villanueva J, Zhang K, Nichols KE, Giraudo CG. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis caused by dominant-negative mutations in STXBP2 that inhibit SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Blood. 2015;125:1566–1577. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-610816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkins MR, Rudd-Schmidt JA, Lopez JA, Ramsbottom KM, Mannering SI, Andrews DM, Voskoboinik I, Trapani JA. Failed CTL/NK cell killing and cytokine hypersecretion are directly linked through prolonged synapse time. J Exp Med. 2015;212:307–317. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gong JH, Maki G, Klingemann HG. Characterization of a human cell line (NK-92) with phenotypical and functional characteristics of activated natural killer cells. Leukemia. 1994;8:652–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selliah N, Zhang M, White S, Zoltick P, Sawaya BE, Finkel TH, Cron RQ. FOXP3 inhibits HIV-1 infection of CD4 T-cells via inhibition of LTR transcriptional activity. Virology. 2008;381:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Endo M, Zoltick PW, Peranteau WH, Radu A, Muvarak N, Ito M, Yang Z, Cotsarelis G, Flake AW. Efficient in vivo targeting of epidermal stem cells by early gestational intraamniotic injection of lentiviral vector driven by the keratin 5 promoter. Mol Ther. 2008;16:131–137. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein E, Ben-Bassat H, Neumann H, Ralph P, Zeuthen J, Polliack A, Vanky F. Properties of the K562 cell line, derived from a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia. Int J Cancer. 1976;18:421–431. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910180405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryceson YT, Pende D, Maul-Pavicic A, Gilmour KC, Ufheil H, Vraetz T, Chiang SC, Marcenaro S, Meazza R, Bondzio I, Walshe D, Janka G, Lehmberg K, Beutel K, zur Stadt U, Binder N, Arico M, Moretta L, Henter JI, Ehl S. A prospective evaluation of degranulation assays in the rapid diagnosis of familial hemophagocytic syndromes. Blood. 2012;119:2754–2763. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-374199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cifaldi L, Prencipe G, Caiello I, Bracaglia C, Locatelli F, De Benedetti F, Strippoli R. Inhibition of Natural Killer Cell Cytotoxicity by Interleukin-6: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Macrophage Activation Syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:3037–3046. doi: 10.1002/art.39295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chavas LM, Ihara K, Kawasaki M, Torii S, Uejima T, Kato R, Izumi T, Wakatsuki S. Elucidation of Rab27 recruitment by its effectors: structure of Rab27a bound to Exophilin4/Slp2-a. Structure. 2008;16:1468–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kukimoto-Niino M, Sakamoto A, Kanno E, Hanawa-Suetsugu K, Terada T, Shirouzu M, Fukuda M, Yokoyama S. Structural basis for the exclusive specificity of Slac2-a/melanophilin for the Rab27 GTPases. Structure. 2008;16:1478–1490. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wulf E, Deboben A, Bautz FA, Faulstich H, Wieland T. Fluorescent phallotoxin, a tool for the visualization of cellular actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:4498–4502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gorelik M, Torok KS, Kietz DA, Hirsch R. Hypocomplementemia associated with macrophage activation syndrome in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and adult onset still’s disease: 3 cases. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:396–397. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zur Stadt U, Beutel K, Kolberg S, Schneppenheim R, Kabisch H, Janka G, Hennies HC. Mutation spectrum in children with primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: molecular and functional analyses of PRF1, UNC13D, STX11, and RAB27A. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:62–68. doi: 10.1002/humu.20274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caiello I, Minnone G, Holzinger D, Vogl T, Prencipe G, Manzo A, De Benedetti F, Strippoli R. IL-6 amplifies TLR mediated cytokine and chemokine production: implications for the pathogenesis of rheumatic inflammatory diseases. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohbayashi N, Mamishi S, Ishibashi K, Maruta Y, Pourakbari B, Tamizifar B, Mohammadpour M, Fukuda M, Parvaneh N. Functional characterization of two RAB27A missense mutations found in Griscelli syndrome type 2. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:365–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orange JS. Formation and function of the lytic NK-cell immunological synapse. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:713–725. doi: 10.1038/nri2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramanan AV, Schneider R. Macrophage activation syndrome–what’s in a name! J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2513–2516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Athreya BH. Is macrophage activation syndrome a new entity? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2002;20:121–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Risma KA, Frayer RW, Filipovich AH, Sumegi J. Aberrant maturation of mutant perforin underlies the clinical diversity of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:182–192. doi: 10.1172/JCI26217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Unal S, Balta G, Okur H, Aytac S, Cetin M, Gumruk F, Ozen S, Gurgey A. Recurrent macrophage activation syndrome associated with heterozygous perforin W374X gene mutation in a child with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35:e205–208. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31827b4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y, Wang Z, Zhang J, Wei Q, Tang R, Qi J, Li L, Ye L, Wang J. Genetic features of late onset primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adolescence or adulthood. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Molleran Lee S, Villanueva J, Sumegi J, Zhang K, Kogawa K, Davis J, Filipovich AH. Characterisation of diverse PRF1 mutations leading to decreased natural killer cell activity in North American families with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Med Genet. 2004;41:137–144. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.011528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cichocki F, Schlums H, Li H, Stache V, Holmes T, Lenvik TR, Chiang SC, Miller JS, Meeths M, Anderson SK, Bryceson YT. Transcriptional regulation of Munc13-4 expression in cytotoxic lymphocytes is disrupted by an intronic mutation associated with a primary immunodeficiency. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1079–1091. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schulert GS, Zhang M, Fall N, Husami A, Kissell D, Hanosh A, Zhang K, Davis K, Jentzen JM, Napolitano L, Siddiqui J, Smith LB, Harms PW, Grom AA, Cron RQ. Whole exome sequencing reveals mutations in hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and macrophage activation syndrome linked genes in fatal cases of H1N1 influenza. J Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv550. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Menasche G, Feldmann J, Houdusse A, Desaymard C, Fischer A, Goud B, de Saint Basile G. Biochemical and functional characterization of Rab27a mutations occurring in Griscelli syndrome patients. Blood. 2003;101:2736–2742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shakoory B, Carcillo JA, Chatham WW, Amdur RL, Zhao H, Dinarello CA, Cron RQ, Opal SM. Interleukin-1 Receptor Blockade Is Associated With Reduced Mortality in Sepsis Patients With Features of Macrophage Activation Syndrome: Reanalysis of a Prior Phase III Trial. Crit Care Med. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001402. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.