Abstract

Objective

To explore the relationship between urinary paraben concentrations and IVF outcomes among women attending an academic fertility center.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Fertility clinic in a hospital setting.

Patient(s)

A total of 245 women contributing 356 IVF cycles.

Intervention(s)

None. Quantification of urinary concentrations of parabens by isotope-dilution tandem mass spectrometry, and assessment of clinical endpoints of IVF treatments abstracted from electronic medical records at the academic fertility center.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Total and mature oocyte counts, proportion of high quality embryos, fertilization rates, and rates of implantation, clinical pregnancy and live births.

Results

The geometric mean of the urinary concentrations of methyl (MP), propyl (PP) and butyl paraben (BP) in our study population were 133, 24 and 1.5 µg/L, respectively. In models adjusted for age, body mass index, race/ethnicity, smoking status and primary infertility diagnosis, urinary MP, PP and BP concentrations were not associated with IVF outcomes, specifically total and mature oocyte counts, proportion of high embryo quality and fertilization rates. Moreover, no significant associations were found between urinary paraben concentrations and rates of implantation, clinical pregnancy and live births.

Conclusion(s)

Urinary paraben concentrations were not associated with IVF outcomes among women undergoing infertility treatments.

Keywords: paraben, IVF outcomes, epidemiology, reproductive health

INTRODUCTION

Parabens are a group of alkyl esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid which are widely used as preservatives in cosmetics, personal care products, pharmaceuticals and food. Parabens are quickly eliminated from the body (1) after exposure through inhalation, dermal contact, and ingestion (2–5). The primary source of paraben exposure is from personal care products, including lotions, cosmetics and cologne/perfume (5). The detection in urine of methyl (MP) and propyl paraben (PP) (the two most commonly used parabens) (3) in over 90% of a representative sample of the US population in the 2011–2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), and of butyl paraben (BP) in over 50% of NHANES participants (6) suggests widespread general population exposure to these compounds. Parabens are considered endocrine disrupting chemicals that are estrogenic (3, 7, 8), and have been shown to bind to both estrogen receptor (ER)α and (ER)β (9, 10). The estrogenic activity of parabens increases with increasing length and branching of the alkyl chain (e.g. BP > PP > MP) (8, 11, 12).

Initially, parabens were considered to be relatively safe compounds with low toxicities. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2006 classified parabens as generally regarded as safe (GRAS) (13). A 2008 report prepared by the Cosmetic Ingredient Review panel concluded that parabens used in cosmetics do not pose a safety risk based on the available data (2). However, in March 2011, the European Scientific Committee on Consumers Safety (SCCS) determined that the human risk of parabens could not be evaluated for lack of data (14). In October 2011, SCCS adopted a clarification to this previous opinion in light of a Danish safety clause, but again in March 2012, contradictory opinions emerged and the opinion did not result in a modification of it in the European Union (EU).

Despite data showing widespread human exposure to parabens, there are a limited number of animal studies on the relationship between parabens and female reproductive health (12, 15–19). Paraben exposure had no effect on pregnancy endpoints on CF-1 mice (19) and rats (18), however rats exposed to parabens in the peripubertal period showed alterations in uterus morphology, ovarian histopathological abnormalities, delay in the age of vaginal opening, decrease in length of the estrous cycle and decreased serum estradiol (12). Other experimental studies showed effects depending on the pregnancy outcomes studied (15–17). Additional toxicological data as well as mechanistic studies are needed to better understand potential effects, if any, of parabens.

Human data are even more limited. Based on earlier data from women in the same cohort as the current analysis, we reported that PP was associated with diminished ovarian reserve (i.e., antral follicle count) (20). Nevertheless, male paraben concentrations were not associated with fertilization or live birth among their female partners undergoing IVF or IUI treatment (21). To our knowledge, there are no epidemiological data on the effects of female paraben exposure on IVF outcomes such as ovarian stimulation response (oocyte yield), endometrial thickness, embryo quality, and rates of fertilization, implantation, clinical pregnancy and live birth. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the association between urinary MP, PP and BP concentrations with these clinical outcomes among women undergoing IVF treatments.

METHODS

Study population

Study participants were women enrolled in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) Study, an ongoing prospective cohort established in 2004 to evaluate environmental and dietary determinants of fertility (22); a pilot study was conducted during 2004 through 2006 and thus there were few women enrolled during this time period. Women between 18 and 45 years old were eligible to participate and approximately 80% of those referred to the research nurses by the clinic physicians agreed to participate and were enrolled. Although this is an ongoing study and we have data on women who have completed at least one IVF cycle to date, urinary paraben concentrations were only measured in samples collected through April 2012. Therefore, the current analysis includes 245 women who completed at least one IVF cycle and provided at least one urine sample for the measurement of parabens for each IVF cycle between November 2004 and April 2012 (n=356 cycles) at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Fertility Center, We a priori excluded from this analysis IVF cycles for which women used an egg donor (n=18) and cryo-thaw cycles (n=34). The study was approved by the Human Studies Institutional Review Boards of the MGH, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Participants signed an informed consent after the study procedures were explained by a trained research study staff and all questions were answered.

Urine sample collection and paraben measurements

Women provided up to two spot urine samples per IVF cycle. The first specimen (not necessarily a fasting sample) collected between Day 3 and Day 9 of the gonadotrophin phase, and the second one, always a fasting sample, collected on the day of oocyte retrieval, prior to the procedure or administration. Although participants were recruited into this study beginning in 2004, the measurement of parabens in urine did not begin until August 2005, when these chemicals were added to the study protocol. Urine was collected in a sterile, clean polypropylene specimen cup at the MGH Fertility Center. Specific gravity (SG), which was used to correct paraben concentrations for urine dilution, was measured at room temperature and within an hour of the urine being produced using a handheld refractometer (National Instrument Company, Inc., Baltimore, MD, USA) calibrated with deionized water before each measurement. SG was measured within a several hours (typically within one hour) after the urine was collected. The urine was then divided into aliquots, frozen at −20°C, and stored long-term at −80 °C. Samples were shipped on dry ice overnight to the CDC where they were stored at or below −40 °C until analysis. The urinary concentrations of total (free + conjugated) MP, PP, and BP were measured using online solid-phase extraction (SPE) coupled with isotope dilution-high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) as described before (23). First, 100 µL of urine was treated with β-glucuronidase/sulfatase (Helix pomatia, H1; Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO, USA) to hydrolyze the paraben-conjugated species. Each paraben was then retained and concentrated on a C18 reversed-phase size-exclusion SPE column (Merck KGaA, Germany), separated from other urine matrix components using a pair of monolithic HPLC columns (Merck KGaA), and detected by negative ion-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-MS/MS. The limits of detection (LOD) were 1.0 µg/L (MP) and 0.2 µg/L (PP, BP). In addition to study samples, each analytical run included low-concentration and high-concentration quality control materials, prepared with spiked pooled human urine, and reagent blanks to assure the accuracy and reliability of the data (23). Paraben concentrations were adjusted for dilution using the following formula [42]: Pc = P [(1.015 − 1)/SG − 1], where Pc is the SG-corrected paraben concentration (µg/L), P is the measured paraben concentration (µg/L) of the urine sample, and 1.015 is the mean SG concentration in the study population. The geometric mean of the SG-adjusted paraben concentrations from two spot urine samples collected during each IVF cycle was used as a measure of cycle-specific urinary paraben concentration. For cycles with only one urine sample (~20%), the paraben concentration for that single urine sample was used as the cycle-specific urinary paraben concentration. paraben concentrations below the LOD were assigned a value equal to the LOD divided by the square root of 2 prior to SG adjustment as described previously (24).

Clinical management and assessment of outcomes

Clinical information was abstracted from the patient’s electronic medical record by research staff. Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and concentration of estradiol (E2) were measured in blood serum, collected on the third day of the menstrual cycle, using an automated electrochemiluminescence immunoassay at the MGH Core Laboratory as described elsewhere (25). Peak E2 concentration, defined as the highest level of E2 prior to oocyte retrieval, was obtained on the day of trigger with Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG). Subsequent to an infertility evaluation, each patient was assigned an infertility diagnosis by a physician at the MGH Fertility Center according to the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) definitions as described elsewhere (25). The participant’s date of birth was collected at entry, and weight and height were measured by trained study staff. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (in kilograms) per height (in meters) squared.

Women underwent one of three controlled ovarian stimulation IVF treatment protocols on day 3 of induced menses after completing a cycle of oral contraceptives: 1) luteal phase GnRH-agonist protocol, 2) follicular phase GnRH-agonist/Flare protocol, or 3) GnRH-antagonist protocol. Lupron dose was reduced at, or shortly after, the start of ovarian stimulation with FSH/hMG in the luteal phase GnRH-agonist protocol. FSH/hMG and GnRH-agonist or GnRH-antagonist was continued to the day of trigger with hCG. Throughout the monitoring phase of the subject’s IVF treatment cycle, estradiol levels were obtained (Elecsys Estradiol II reagent kit, Roche Diagnostics). Oocyte retrieval was completed when at least 3 follicle dimensions on transvaginal ultrasound reached 16–18 mm and the E2 level reached at least 500 pg/mL. Patients were monitored during gonadotropin stimulation for serum E2, follicle size measurements and counts, and endometrial thickness through 2 days before egg retrieval. hCG was administered approximately 36 hours before the scheduled egg retrieval procedure to induce oocyte maturity. Details of egg retrieval have been previously described (25).

Embryologists determined the total number of oocytes retrieved per cycle and classified them as germinal vesicle, metaphase I, metaphase II (MII) or degenerated. Oocytes underwent either conventional IVF or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) as clinically indicated. Embryologists determined fertilization rate 17–20 hours after insemination as the number of oocytes with two pronuclei divided by the number of MII oocytes inseminated. We classified embryo quality based on morphology and number of blastomeres, ranging from 1 (best) to 5 (worst) on day 2 and 3. For analysis we classified embryos as best quality if they had 4 cells on day 2, 8 cells on day 3, and a morphologic quality score of 1 or 2 on days 2 and 3 (26). An overall score of 1 or 2 was considered high quality, 3 was considered intermediate quality and 4 or 5 indicated poor quality embryos.

In women who underwent an embryo transfer, clinical outcomes were assessed. Implantation was defined as a serum β-hCG level > 6 mIU/mL, typically measured 17 days (range 15–20 days) after egg retrieval. An elevation in β-hCG with the confirmation of an intrauterine pregnancy on an ultrasound at 6 weeks was considered a clinical pregnancy. A live birth was defined as the birth of a neonate on or after 24 weeks gestation.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and baseline reproductive characteristics of the women were presented using median ± interquartile ranges (IQRs) or percentages. Women’s exposures to each paraben were categorized into quartiles of urinary paraben concentrations (based on the woman’s cycle-specific SG-adjusted geometric mean as described above) with the lowest quartile considered as the reference group. Associations between urinary paraben concentrations and demographics and baseline reproductive characteristics were evaluated using Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Multivariable generalized linear mixed models with random intercepts were used to evaluate the association between urinary paraben (MP, PP, and BP) concentrations and IVF outcomes. A Poisson distribution and log link function were specified for oocyte counts, and a binomial distribution and logit link function were specified for embryo quality, fertilization rates, and clinical outcomes (implantation, clinical pregnancy and live birth). To allow for better interpretation of the results, population marginal means (27) are presented adjusting for all the covariates in the model.

Confounding was assessed using prior knowledge on biological relevance through the use of directed acyclic graphs and descriptive statistics from our study population (28). The variables considered as potential confounders included factors previously related to IVF outcomes in this and other studies, and factors associated with paraben exposure and IVF outcomes in this study, regardless of whether they had been previously described as predictors of IVF outcomes (Table 1). Final models were adjusted for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), race (white vs nonwhite), smoking status (never vs ever), and infertility diagnosis (male factor, female factor, unexplained). All tests were two-tailed and the level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 245 women in the Environment and Reproductive Health Study (EARTH).

| Median (IQR) or N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |

| Age, years | 35.0 (32.0, 38.0) |

| Race/Ethnic group, n (%) | |

| White/Caucasian | 203 (82.8) |

| Black | 6 (2.5) |

| Asian | 20 (8.2) |

| Other | 16 (6.5) |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 23.1 (21.1, 25.9) |

| Ever smoker, n (%) | 68 (27.8) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| < College graduate | 19 (7.2) |

| College graduate | 75 (32.8) |

| Graduate degree | 135 (59.0) |

| Baseline Reproductive characteristics | |

| Previous IUI, n (%) | 116 (47.4) |

| Previous IVF, n (%) | 59 (24.1) |

| Initial infertility diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Male factor | 92 (37.6) |

| Female factor | 73 (29.7) |

| Diminished Ovarian Reserve | 16 (6.5) |

| Endometriosis | 18 (7.3) |

| Ovulation Disorders | 22 (9.0) |

| Tubal | 15 (6.1) |

| Uterine | 2 (0.8) |

| Unexplained | 80 (32.7) |

| Initial treatment protocol, n (%) | |

| Antagonist | 29 (11.8) |

| Flarea | 40 (16.3) |

| Luteal phase agonistb | 176 (72.8) |

| Initial ICSI cycles, n (%) | 127 (55.2) |

| E2 Trigger Levels, pmol/L | 2028 (1509, 2614) |

| Day 3 FSH Levels, IU/L | 6.9 (5.8, 8.3) |

| Embryo Transfer Day, n (%) | |

| No embryos transferred | 26 (10.6) |

| Day 2 | 9 (3.7) |

| Day 3 | 132 (53.9) |

| Day 5 | 78 (31.8) |

| Number of Embryos Transferred, n (%) | |

| No embryos transferred | 26 (10.6) |

| 1 embryo | 30 (12.2) |

| 2 embryos | 144 (58.8) |

| 3+ embryos | 45 (18.4) |

Follicular phase GnRH-agonist/Flare protocol.

Luteal phase GnRH-agonist protocol.

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; N, number; IUI, intrauterine insemination, IVF, in vitro fertilization, ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

RESULTS

The 245 women included in this analysis had a median age and BMI [Interquartile Range (IQR)] of 35.0 years (32.0, 38.0) and 23.1 kg/m2 (21.1, 25.9), respectively (Table 1). Women were predominantly Caucasian (83%) and 72% had never smoked. The primary SART diagnosis at enrollment was male factor (38%) followed by unexplained infertility (33%) and female factor infertility (30%). Luteal phase GnRH-agonist protocols were the most commonly used stimulation protocol in the first treatment cycle (73%). Women had a median day 3 FSH and E2 trigger of 6.9 IU/L and 2028 pmol/L, respectively (Table 1). SG-adjusted geometric mean PP and BP urinary concentrations were higher among thinner women and SG-adjusted geometric mean urinary concentrations of the three parabens were lower in smokers (data not shown). Also, the SG-adjusted geometric mean BP urinary concentrations were lower in white compared to non-white women (data not shown).

The SG-adjusted geometric mean MP, PP and BP urinary concentrations for the 667 samples provided by the 245 women (contributing to 356 IVF cycles) were 133, 24 and 1.5 µg/L, respectively (Table 2). These values were slightly higher than those for females of all ages in the general population (NHANES 2011–2012 (95, 16 and 1.1 µg/L, respectively)) (6), and slightly lower than those previously published in our early publication on a subset of the same cohort of women (20). Two urine samples were collected in 87% (311/356) of the IVF cycles. Detectable concentrations of MP, PP and BP were measured in 99.7% (665/667), 98.8% (659/667) and 72.6% (484/667), respectively, of samples (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of cycle-specific geometric mean of urinary parabens concentrations (µg/L) among 245 women in the Environment and Reproductive Health Study (EARTH) undergoing 356 IVF cycles (667 urine samples).

| Percentile | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Rate |

GM (SD) | Min | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th | Max | |

| Methyl-P | 99.7 | 135 (10.4) | <1.0 | 21.0 | 52.2 | 163 | 380 | 766 | 1104 | 3182 |

| SG-adj Methyl-P | 133 (9.73) | 1.29 | 20.6 | 59.1 | 166 | 353 | 637 | 953 | 2391 | |

| Propyl-P | 98.8 | 24.8 (2.36) | <0.2 | 1.94 | 8.21 | 31.4 | 90.2 | 210 | 348 | 1264 |

| SG-adj Propyl-P | 24.4 (2.27) | <0.2 | 1.89 | 8.20 | 33.3 | 91.6 | 194 | 283 | 818 | |

| Butyl-P | 72.6 | 1.50 (0.15) | <0.2 | <0.2 | 0.29 | 1.18 | 5.77 | 25.8 | 58.5 | 146 |

| SG-adj Butyl -P | 1.47 (0.15) | <0.2 | <0.2 | 0.31 | 1.23 | 5.31 | 25.9 | 43.7 | 137 | |

Abbreviations: Max, maximum; Min, minimum; SG-adj, specific-gravity adjusted. All values below LOD (<LOD) were assigned a value equal to the LOD divided by √2. Zero (0%), 1 (0.28%) and 52 (14.6%) cycle-specific methyl, propyl and butyl-paraben concentrations, respectively, were < LOD and are included in the percentiles. Two (0.3%), 8 (1.2%) and 183 (27.4%) individual urine samples had methyl, propyl and butylparaben concentrations < LOD, respectively. Limit of detection for methyl-paraben (1.0 µg/L), butyl and propyl-parabens (0.20 µg/L).

SG-adjusted urinary MP, PP and BP concentrations were not associated with IVF outcomes in our study population (Table 3). Specifically, no significant dose-response associations were observed between urinary paraben concentrations with total and mature oocyte yields, proportion of best embryo quality and fertilization rates, either overall (Table 3) or when IVF and ICSI cycles were examined separately (data not shown) in unadjusted models. Similar trends were found when models were adjusted for age, BMI, race/ethnicity, smoking status and primary infertility diagnosis.

Table 3.

Specific gravity adjusted cycle specific urinary parabens concentrations in relation to IVF outcomes among 245 women contributing to 356 fresh IVF cycles in the Environment and Reproductive Health Study (EARTH).

|

Total Oocyte Yield Estimated count (95% CI) |

MII Oocyte Yield Estimated count (95% CI) |

>1 Best embryo qualityb Estimated proportion (95% CI) |

Fertilization Estimated rate (95% CI) |

|||||

|

Urinary methyl-paraben concentrations (µg/L) |

Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda |

| Q1 [1.29–59.1] | 11.0 (9.9, 12.3) | 10.9 (9.9, 12.1) | 9.3 (8.3, 10.3) | 9.1 (8.2, 10.1) | 0.38 (0.28, 0.49) | 0.39 (0.28, 0.50) | 0.69 (0.64, 0.73) | 0.69 (0.64, 0.74) |

| Q2 [59.2–166] | 11.2 (10.1, 12.3) | 11.0 (9.9, 12.1) | 9.7 (8.8, 10.8) | 9.6 (8.7, 10.6) | 0.38 (0.28, 0.50) | 0.37 (0.27, 0.49) | 0.70 (0.66, 0.75) | 0.70 (0.65, 0.75) |

| Q3 [167–352] | 11.0 (9.9, 12.2) | 10.9 (9.8, 12.0) | 9.2 (8.3, 10.2) | 9.1 (8.2, 10.1) | 0.55 (0.44, 0.65) | 0.55 (0.44, 0.66) | 0.71 (0.67, 0.76)* | 0.72 (0.67, 0.76) |

| Q4 [354–2391] | 10.2 (9.2, 11.3) | 10.1 (9.1, 11.2) | 8.7 (7.9, 9.7) | 8.7 (7.8, 9.6) | 0.41 (0.31, 0.53) | 0.40 (0.30, 0.52) | 0.74 (0.69, 0.78) | 0.74 (0.69, 0.78) |

| p, trend | 0.22 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

|

Urinary propyl-paraben concentrations (µg/L) |

Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda |

| Q1 [<LOD –8.05] | 11.4 (10.3, 12.7) | 11.4 (10.3, 12.6) | 9.6 (8.7, 10.7) | 9.5 (8.6, 10.6) | 0.45 (0.34, 0.56) | 0.46 (0.35, 0.57) | 0.68 (0.63, 0.73) | 0.69 (0.63, 0.73) |

| Q2 [8.36–32.1] | 10.5 (9.5, 11.5) | 10.3 (9.4, 11.4) | 9.0 (8.2, 10.0) | 8.9 (8.1, 9.9) | 0.40 (0.29, 0.51) | 0.39 (0.28, 0.50) | 0.73 (0.69, 0.77) | 0.73 (0.69, 0.77) |

| Q3 [34.6–90.6] | 11.2 (10.1, 12.4) | 11.1 (10.1, 12.3) | 9.6 (8.6, 10.6) | 9.5 (8.6, 10.5) | 0.45 (0.34, 0.56) | 0.45 (0.34, 0.56) | 0.70 (0.66, 0.75) | 0.71 (0.66, 0.75) |

| Q4 [92.6–818] | 10.3 (9.3, 11.5) | 10.1 (9.1, 11.2) | 8.7 (7.9, 9.7) | 8.5 (7.7, 9.5) | 0.43 (0.33, 0.55) | 0.43 (0.32, 0.54) | 0.72 (0.67, 0.76) | 0.72 (0.67, 0.77) |

| p, trend | 0.30 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.28 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.49 | 0.44 |

|

Urinary butyl-paraben concentrations (µg/L) |

Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda |

| Q1 [<LOD–0.31] | 10.7 (9.6, 11.9) | 10.6 (9.5, 11.8) | 9.0 (8.1, 10.0) | 8.9 (8.0, 9.9) | 0.35 (0.26, 0.47) | 0.35 (0.25, 0.47) | 0.70 (0.65, 0.75) | 0.70 (0.65, 0.75) |

| Q2 [0.32–1.20] | 10.7 (9.7, 11.9) | 10.5 (9.5, 11.6) | 9.2 (8.3, 10.2) | 9.0 (8.1, 9.9) | 0.43 (0.33, 0.55) | 0.44 (0.33, 0.55) | 0.70 (0.65, 0.74) | 0.70 (0.65, 0.74) |

| Q3 [1.26–5.29] | 11.3 (10.2, 12.4) | 11.2 (10.1, 12.4) | 9.7 (8.7, 10.7) | 9.7 (8.7, 10.7) | 0.47 (0.36, 0.58) | 0.47 (0.36, 0.58) | 0.75 (0.70, 0.79) | 0.75 (0.70, 0.79) |

| Q4 [5.33–137] | 10.7 (9.6, 11.9) | 10.6 (9.5, 11.8) | 9.1 (8.1, 10.0) | 8.9 (7.9, 9.9) | 0.47 (0.36, 0.58) | 0.46 (0.35, 0.57) | 0.69 (0.64, 0.74) | 0.69 (0.64, 0.74) |

| p, trend | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.68 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.90 | 0.96 |

Adjusted for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking status (never and ever), race (white and others) and infertility diagnosis (male, female and unexplained).

We classified embryos as best quality if they had 4 cells on day 2, 8 cells on day 3, and a morphologic quality score of 1 or 2 on days 2 and 3.

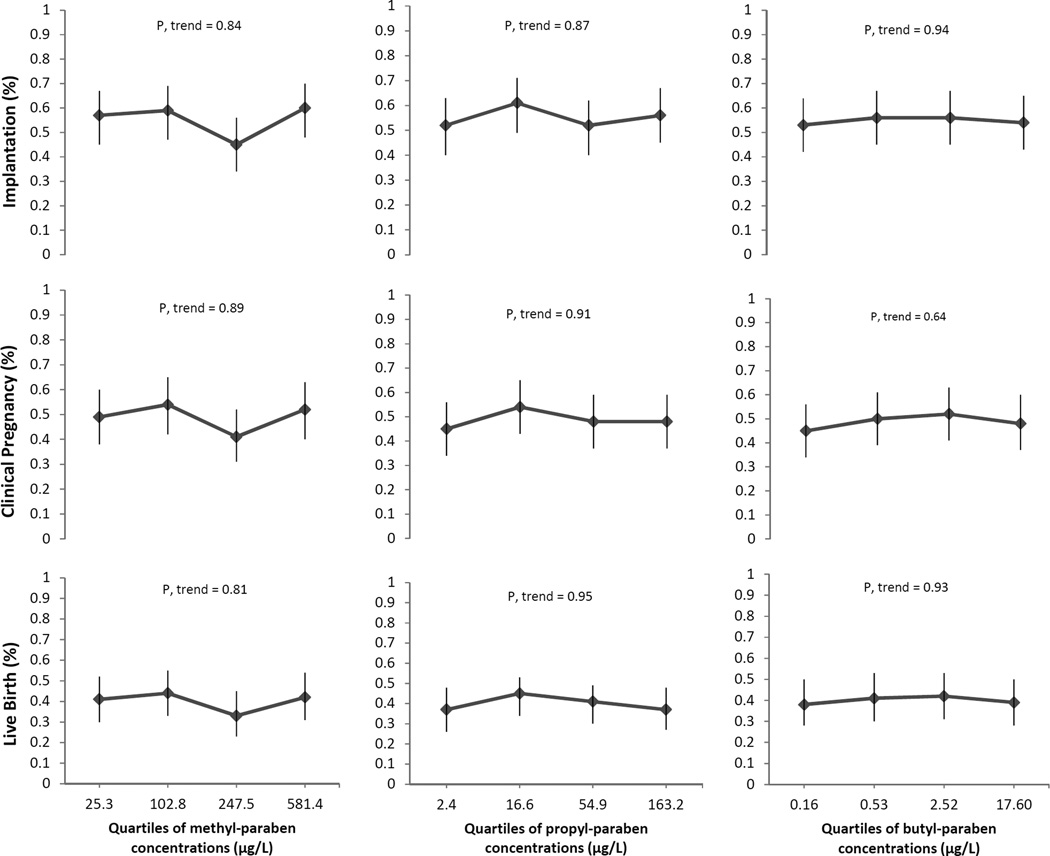

Associations between SG-adjusted urinary MP, PP and BP concentrations with implantation, clinical pregnancy and live birth rates per initiated cycle were examined (Figure 1). No significant associations were found between urinary paraben concentrations and these clinical outcomes in unadjusted and adjusted models. The adjusted estimate differences in proportions with implantation, clinical pregnancy and live birth for women in the highest quartile of urinary MP concentration compared with women in the lowest quartile were +0.03, +0.03 and +0.01, respectively. The adjusted estimate differences in implantation and live birth rates for women in the highest quartile of urinary PP concentration compared with women in the lowest quartile were +0.01, and −0.02, respectively, without any difference in clinical pregnancy. The adjusted estimate differences in proportions with implantation, clinical pregnancy and live birth for women in the highest quartile of urinary BP concentration were comparable to women in the lowest quartile were +0.01, +0.03 and +0.01, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Relathionships between quartiles of urinary parabens concentrations (µg/L) with implantation, clinical pregnancy and live birth (n=356 fresh cycles).

Clinical outcomes (95% CI) per initiated cycle across quartiles of urinary parabens concentrations (represented by the medians for each quartile) are presented. Models are adjusted for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), race (white and nonwhite), smoking status (never and ever) and infertility diagnosis (male, female and unexplained). Implantation was defined as a serum β-hCG level > 6 mIU/mL typically measured 17 days (range 15–20 days) after egg retrieval, clinical pregnancy as the presence of an intrauterine pregnancy confirmed by ultrasound and live birth as the birth of a neonate on or after 24 weeks gestation.

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the association of urinary concentrations of MP, PP and BP with IVF outcomes in this prospective cohort study among women attending a fertility clinic. Despite our previous publication reporting an association of higher urinary paraben concentrations with diminished ovarian reserve (i.e., AFC) in a subset of women from the same cohort as the current study (20), we found no associations of urinary paraben concentrations with measures of response to ovarian stimulation (oocyte yield), embryo quality, and fertilization rates. Moreover, urinary paraben concentrations were not associated with rates of implantation, clinical pregnancy and live birth.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the association of urinary paraben concentrations with clinical outcomes among women undergoing IVF treatments. Surprisingly, despite widespread human exposure to parabens, there are very limited data from experimental studies in animals on potential effects on female reproductive health (15,18,19). Shaw and deCatanzaro (2009) did not find an association between BP and PP with implantation sites and offspring survival following in utero exposure of CF-1 mice (19). Similarly, oral administration of BP did not alter maternal ovarian E2 level in a study conducted in rats (18). However, other experimental studies have shown effects of parabens for other outcomes (12, 15–17). For example, subcutaneous administration of BP to pregnant rats resulted in a decrease in the proportion of live born rats but did not affect the weight of the genital organs of the female offspring (15). Also, the number of implantations sites and number of live and dead fetuses were not affected by an utero exposure to BP on Sprague-Dawley rats, but there was a significant weight change in ovaries after exposure to parabens (17). Moreover, Vo and colleagues (2010) observed alterations in uterus morphology, ovarian histopathological abnormities, delay in the date of vaginal opening, decrease in length of the estrous cycle and decreased serum estradiol in peripubertal exposed rats to parabens (12).

We previously explored the association between urinary MP, PP and BP concentrations with ovarian aging in 192 women from the same cohort study (20). We found suggestive evidence of a negative relationship between urinary PP concentrations and antra follicle count (AFC), which is considered a marker of ovarian reserve. In addition, higher urinary PP concentrations were associated with a higher day-3 FSH, which is consistent with PP’s negative association with AFC, suggesting that exposure to PP may adversely affect ovarian reserve, and thus contribute to ovarian aging, among women attending a fertility clinic (20). Our urinary paraben concentrations were slightly lower than those reported previously in Smith’s paper (20), and also compared with other US population of women (6, 29). Moreover, the urinary paraben concentrations in this study were, however, a little lower than those measured in Spanish pregnant women (30) and higher compared with those measured among Japanese pregnant women (31). However, none of these studies assessed the effect of parabens on female reproductive endpoints.

The present study has some limitations. Due to its design, it may not be possible to extrapolate the study findings to the general population of couples conceiving without medical intervention. However, these findings may be applicable to other women seeking infertility treatment (32). Also, misclassification of paraben exposure based on concentrations from spot urine samples is possible because parabens are short-lived chemicals (1) and exposures are likely to be episodic in nature potentially leading to attenuated associations. Although one urine sample may reasonably represent several months of exposure to parabens as we previously published (33), we also collected multiple samples and this should further reduce exposure misclassification. Strengths of our study include its prospective design which minimizes the possibility of reverse causation, the comprehensive adjustment of possible confounding variables, and adequate power to detect clinically relevant differences in clinical outcomes between women in the highest and lowest quartiles of urinary paraben concentrations.

In conclusion, urinary methyl, propyl and butylparaben concentrations were not associated with clinical outcomes among women undergoing IVF treatments at a fertility clinic. The lack of associations suggests that paraben exposure at the levels experienced by this fertility clinic population do not affect IVF reproductive outcomes. Despite the null findings and due to widespread general population exposure, there remains the need for studies on other potential health effects of parabens, including effects on children’s health and male reproductive function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Xiaoyun Ye, Xiaoliu Zhou, Josh Kramer and Tao Jia of CDC for their technical assistance with paraben measurements. We also acknowledge all members of the EARTH study team, specifically the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health research nurse Myra G. Keller, research staff Ramace Dadd and Patricia Morey, physicians and staff at Massachusetts General Hospital fertility center and a special thanks to all the study participants.

STUDY FUNDING: NIH grants R01ES022955, R01ES009718, R01ES000002 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and grant T32DK00770316 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION TO MANUSCRIPT: R.H. was involved in study concept and design, and critical revision for important intellectual content of the manuscript. P.L.W contributed to method modification and provided statistical expertise. L.M.A analyzed data, drafted the manuscript and had a primary responsibility for final content; L.M.A, M.E.S, P.L.W. and R.H. interpreted the data; Y-H.C. reviewed the statistical analysis; T.L.T, J.B.F and A.M.C. were involved in acquisition of the data. All authors were involved in the critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to declare.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Janjua NR, Frederiksen H, Skakkebaek NE, Wulf HC, Andersson AM. Urinary excretion of phthalates and paraben after repeated whole-body topical application in humans. International journal of andrology. 2008;31:118–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen F. Final amended report on the safety assessment of methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, isopropylparaben, butylparaben, isobutylparaben, and benzylparaben as used in cosmetic products. Int J Toxicol. 2008;27(Suppl 4):182. doi: 10.1080/10915810802548359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soni MG, Carabin IG, Burdock GA. Safety assessment of esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid (parabens) Food Chem Toxicol. 2005;43:985–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodge LE, Kelley KE, Williams PL, Williams MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Missmer SA, et al. Medications as a source of paraben exposure. Reprod Toxicol. 2015;52:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun JM, Just AC, Williams PL, Smith KW, Calafat AM, Hauser R. Personal care product use and urinary phthalate metabolite and paraben concentrations during pregnancy among women from a fertility clinic. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2014;24:459–466. doi: 10.1038/jes.2013.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta: GA: US. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. Feb, Fourth Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, Updated Tables. http://wwwcdcgov/biomonitoring/pdf/FourthReport_UpdatedTables_Feb2015pdf 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golden R, Gandy J, Vollmer G. A review of the endocrine activity of parabens and implications for potential risks to human health. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2005;35:435–458. doi: 10.1080/10408440490920104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Routledge EJ, Parker J, Odum J, Ashby J, Sumpter JP. Some alkyl hydroxy benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;153:12–19. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okubo T, Yokoyama Y, Kano K, Kano I. ER-dependent estrogenic activity of parabens assessed by proliferation of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells and expression of ERalpha and PR. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001;39:1225–1232. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(01)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomez E, Pillon A, Fenet H, Rosain D, Duchesne MJ, Nicolas JC, et al. Estrogenic activity of cosmetic components in reporter cell lines: parabens, UV screens, and musks. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2005;68:239–251. doi: 10.1080/15287390590895054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Byford JR, Shaw LE, Drew MG, Pope GS, Sauer MJ, Darbre PD. Oestrogenic activity of parabens in MCF7 human breast cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;80:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vo TT, Yoo YM, Choi KC, Jeung EB. Potential estrogenic effect(s) of parabens at the prepubertal stage of a postnatal female rat model. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;29:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FDA. Food and Drug Administration. GRAS Substances (SCOGS) Database. [accessed 6 July 2015];2007 Available: http://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/productsingredients/ingredients/ucm128042.htm.

- 14.SCCS. Scientific Committee on consumer Safety. Opinion on parabens SCCS/1348/10. 2011 http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/consumer_safety/docs/sccs_o_041.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang KS, Che JH, Ryu DY, Kim TW, Li GX, Lee YS. Decreased sperm number and motile activity on the F1 offspring maternally exposed to butyl p-hydroxybenzoic acid (butyl paraben) J Vet Med Sci. 2002;64:227–235. doi: 10.1292/jvms.64.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taxvig C, Vinggaard AM, Hass U, Axelstad M, Boberg J, Hansen PR, et al. Do parabens have the ability to interfere with steroidogenesis? Toxicol Sci. 2008;106:206–213. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daston GP. Developmental toxicity evaluation of butylparaben in Sprague-Dawley rats. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2004;71:296–302. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boberg J, Metzdorff S, Wortziger R, Axelstad M, Brokken L, Vinggaard AM, et al. Impact of diisobutyl phthalate and other PPAR agonists on steroidogenesis and plasma insulin and leptin levels in fetal rats. Toxicology. 2008;250:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw J, deCatanzaro D. Estrogenicity of parabens revisited: impact of parabens on early pregnancy and an uterotrophic assay in mice. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;28:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith KW, Souter I, Dimitriadis I, Ehrlich S, Williams PL, Calafat AM, et al. Urinary Paraben Concentrations and Ovarian Aging among Women from a Fertility Center. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2013;121:1299–1305. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dodge LE, Williams PL, Williams MA, Missmer SA, Toth TL, Calafat AM, et al. Paternal Urinary Concentrations of Parabens and Other Phenols in Relation to Reproductive Outcomes among Couples from a Fertility Clinic. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:665–671. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hauser R, Meeker JD, Duty S, Silva MJ, Calafat AM. Altered semen quality in relation to urinary concentrations of phthalate monoester and oxidative metabolites. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2006;17:682–691. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000235996.89953.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye X, Kuklenyik Z, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Automated on-line column-switching HPLC-MS/MS method with peak focusing for the determination of nine environmental phenols in urine. Anal Chem. 2005;77:5407–5413. doi: 10.1021/ac050390d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meeker JD, Ehrlich S, Toth TL, Wright DL, Calafat AM, Trisini AT, et al. Semen quality and sperm DNA damage in relation to urinary bisphenol A among men from an infertility clinic. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;30:532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mok-Lin E, Ehrlich S, Williams PL, Petrozza J, Wright DL, Calafat AM, et al. Urinary bisphenol A concentrations and ovarian response among women undergoing IVF. International journal of andrology. 2010;33:385–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veeck L, Zaninovic N. An atlas of human blastocysts. New York: Parthenon Publishing Group; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Searle SR, Speed FM, Milliken GA. Population marginal means in the linear model: an alternative to least square means. Am Stat. 1980;34:216–221. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weng H-Y, Hsueh Y-H, Messam LLM, Hertz-Picciotto I. Methods of Covariate Selection: Directed Acyclic Graphs and the Change-in-Estimate Procedure. American journal of epidemiology. 2009;169:1182–1190. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koeppe ES, Ferguson KK, Colacino JA, Meeker JD. Relationship between urinary triclosan and paraben concentrations and serum thyroid measures in NHANES 2007–2008. Sci Total Environ. 2013:445–446. 299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casas L, Fernandez MF, Llop S, Guxens M, Ballester F, Olea N, et al. Urinary concentrations of phthalates and phenols in a population of Spanish pregnant women and children. Environ Int. 2011;37:858–866. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shirai S, Suzuki Y, Yoshinaga J, Shiraishi H, Mizumoto Y. Urinary excretion of parabens in pregnant Japanese women. Reprod Toxicol. 2013;35:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephen EH, Chandra A. Use of infertility services in the United States: 1995. Fam Plann Perspect. 2000;32:132–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith KW, Braun JM, Williams PL, Ehrlich S, Correia KF, Calafat AM, et al. Predictors and variability of urinary paraben concentrations in men and women, including before and during pregnancy. Environmental health perspectives. 2012;120:1538–1543. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]