Abstract

The currently used vaccine strategy to combat influenza A virus (IAV) aims to provide highly specific immunity to circulating seasonal IAV strains. However, the outbreak of 2009 influenza pandemic highlights the danger in this strategy. Here, we tested the hypothesis that universal vaccination that offers broader but weaker protection would result in cross protective T-cell responses after primary IAV infection, which would subsequently provide protective immunity against future pandemic strains. Specifically, we used tandem repeat M2e epitopes on virus-like particles (M2e5x VLP) that induced heterosubtypic immunity by eliciting antibodies to a conserved M2e epitope. M2e5x VLP was found to be superior to strain-specific current split vaccine in conferring heterosubtypic cross protection and in equipping the host with cross-protective lung-resident nucleoprotein-specific memory CD8+ T cell responses to a subsequent secondary infection with a new pandemic potential strain. Immune correlates for subsequent heterosubtypic immunity by M2e5x VLP vaccination were found to be virus-specific CD8+ T cells secreting IFN-γ and expressing lung-resident memory phenotypic markers CD69+ and CD103+ as well as M2e antibodies. Hence, vaccination with M2e5x VLP may be developable as a new strategy to combat future pandemic outbreaks.

Keywords: Influenza virus, M2e5x VLPs, heterosubtypic immunity, tissue-resident memory T cells

Introduction

Influenza A viruses (IAVs) are divided into subtypes based on hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins on the surface of the virus (1). At present, 18 different HA and 11 different NA molecules are known to exist. Wild birds are the primary natural reservoir for most subtypes of IAVs (2). The interspecies transmission often causes a devastating consequence. For example, three pandemics in the 20th century, in 1918 (H1N1), 1957 (H2N2), and 1968 (H3N2), resulted in many millions of deaths worldwide (3). Furthermore, the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic has claimed 18,500 laboratory-confirmed deaths in over 200 countries (4). The genomes of pandemic viruses originated either wholly or partly from nonhuman reservoirs, and the HA genes ultimately derived from avian influenza viruses (5). It can be a panic if novel subtypes such as H7N9 or highly pathogenic H5N1 IAV acquire effective transmissibility among humans.

Development of a universal influenza vaccine has been a challenge since the first vaccination a half century ago. Heterosubtypic immunity has mainly been demonstrated in animal models with virus infections (6-9), and there is also evidence for the presence of cross-protective immunity in humans (10-12). It is indicated that cell-mediated immunity in particular CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes contributes to heterosubtypic immunity (6, 13).

Current influenza vaccines are not effective in inducting virus-specific CD8+ T cells (14-16). Therefore, there is a concern that seasonal vaccination is not effective in preventing future pandemic strains. The extracellular domain of M2 (M2e) is well conserved across human influenza A subtypes (17-18). Therefore, M2e-based vaccines have been investigated as a promising candidate for a universal influenza vaccine with broad-spectrum protection (19-21).

Virus-like particles presenting highly conserved M2e tandem repeat epitopes (M2e5x VLP) were demonstrated to be effective in conferring cross protection against H1, H3, and H5 subtype influenza viruses by reducing lung viral loads and morbidity (22). Here, we hypothesized that M2e5x VLP immunization would induce cross protective M2e antibodies as well as prevent severe disease while enabling the induction of virus-specific memory T cells after primary infection. This study demonstrates that M2e5x VLPs could be more effective in inducing M2e antibodies and conferring heterosubtypic cross protection than current split vaccines. More significantly, after primary infection, mice that were immunized with M2e5x VLP but not split vaccines were found to acquire strong heterosubtypic immunity and CD8+ lung-resident memory T cells (TRM) specific for highly conserved influenza nucleoprotein, conferring long-lived cross protection.

Materials and methods

Viruses, vaccine, and M2e5x VLP

IAV A/California/04/2009 (H1N1; a gift from Dr. Richard Webby), reassortant A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (rgH5N1 containing H5N1-derived NA and HA with polybasic residues removed, and 6 internal genes from A/PR/8/1934), A/Philippines/2/1982 (H3N2; a gift from Dr. Huan Nguyen), and reassortant A/Mandarin Duck/Korea/PSC24-24/2010 (avian rgH5N1 containing HA with polybasic residues removed, NA and M genes from A/PSC24-24, and the remaining backbone genes from A/PR/8/1934 virus) were propagated in 10-day-old embryonated hen’s eggs as previously described (23). Purified viruses were produced by treating the virus with formalin at a final concentration of 1:4,000 (v/v) as described previously (24). Commercial influenza monovalent split vaccine (Green Flu-S; Green Cross, Korea) derived from A/California/7/2009 NYMC X-179A (H1N1) virus was used in this study. M2e5x VLP that contain tandem repeat of heterologous M2e derived from human (2×), swine (1×), and avian (2×) influenza viruses was prepared using the insect cell expression system as described previously (22).

Immunization and challenge

Female BALB/c mice (6-8 wk old) were intramuscularly immunized with 0.6 μg of human split vaccine (total protein) or 10 μg of M2e5x VLP or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at week 0 and 4. Immunized mice were then intranasally challenged with a sub-lethal dose (0.8 × LD50) of A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus at 4 weeks after boost immunization. At 4 months after primary infection, groups of mice were challenged with a 10 LD50 of rgH5N1 A/Vietnam/1203/2004. After challenge with IAVs, survival rate and weight loss were monitored daily for 14 days p.i.. All animal experiments presented in this study were approved by the Georgia State University IACUC review boards.

Determination of antibody responses, lung viral titers

The antibody levels specific to M2e or influenza virus (2 μg/ml) were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (25). Receptor destroying enzyme (RDE, Denka Seiken, Japan) treated serum samples were used for HI assay as previously described (26-27). Lung viral titers were determined as described in detail previously (28). Briefly, the 50% egg infectious dose (EID50) in 10-day-old embryonated hen’s eggs was determined with 10-fold serial dilutions of the supernatant, incubated for 48 h at 37 °C, and calculated by the Reed-Muench method (29).

Flow cytometric analysis

For cell phenotype analysis, the cells were stained with fluorophore-labeled surface markers. Anti-mouse CD16/32 was used as a Fc receptor blocker and then, an antibody cocktail which contained anti-mouse CD4-PE-Cy7, CD8α-V500, CD44-APC-Cy7, CD62L-PerCP, CD69-FITC, CD103-pacific blue, and APC-labelled tetramer (NIH tetramer core facility) specific for influenza NP147-155 H-2Kd (TYQRTRALV) (30) was used to treat the cells.

To evaluate intracellular cytokine production, lung cells were stimulated with NP147-155 peptide-pulsed bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) for 5 days as previously described (31-33), surface-stained for anti-CD11c-PE-Cy7, anti-CD4-APC and anti-CD8α-PE antibodies and then were permeable using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences). Intracellular cytokines were revealed by staining the cells with anti-IFN-γ-APC-Cy7 antibodies. All antibodies except tetramers were purchased from eBiosciences or BD Bioscience. Stained cells were analyzed using LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc.).

Preparation and in vitro stimulation of bone marrow derived dendritic cells (BMDCs)

BMDCs were prepared from bone marrow cells of C57BL/6 treated with 10 ng/ml of mouse granulocytes-macrophages colony stimulating factor for 6 days. BMDCs were stimulated with 5 μg/ml of H-2Kd-restricted NP147-155 peptide (TYQRTRALV) at 2 × 105 cells/ml in 6-well plate for 2 h. After wash, BMDCs were cocultured with allogeneic BALB/c lung cells with the ratio of 1:10 for BMDCs to lung cells. After 5 days, the cells were washed and the activation of the T cells was assessed by flow cytometry.

In vivo protection assay of immune sera

It was reported that M2e-specific antibodies contributed to cross protection although these M2e antibodies lack in vitro virus neutralizing activity (22, 34-36). To further determine whether M2e5x immune sera would contribute to cross-protection against different subtypes of influenza A viruses, we carried out an in vivo protection assay as previously described (22, 37). In brief, heat-inactivated immunized or naïve sera were mixed with a lethal dose (10 × LD50) of A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (rgH5N1), a lethal dose (6 × LD50) of A/Philippines/2/1982 (H3N2) or A/Mandarin Duck/Korea/PSC24-24/2010 (avian rgH5N1 with avian M2) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Naive BALB/c mice were infected with a mixture of virus and sera, and were monitored for their survival rates and weight loss for 14 days p.i..

In vivo depletion of immune cells

Lung-resident CD8+ T cells were depleted by intranasal injection of rat mAb clone 2.43 (10 μg/mouse, BioXCell, West Lebanon, NH) 4 days before challenge. The population of CD8+ T cells in the spleen, lungs, and mediastinal lymph nodes was confirmed by flow cytometry at day 4 after inoculation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism software. Data are presented as means ± error of the mean (SEM). Differences between groups were analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or 2-way ANOVA where appropriate. P-values less than 0.05 were regarded as significant.

Results

M2e5x VLP is superior to split vaccine in conferring cross protection

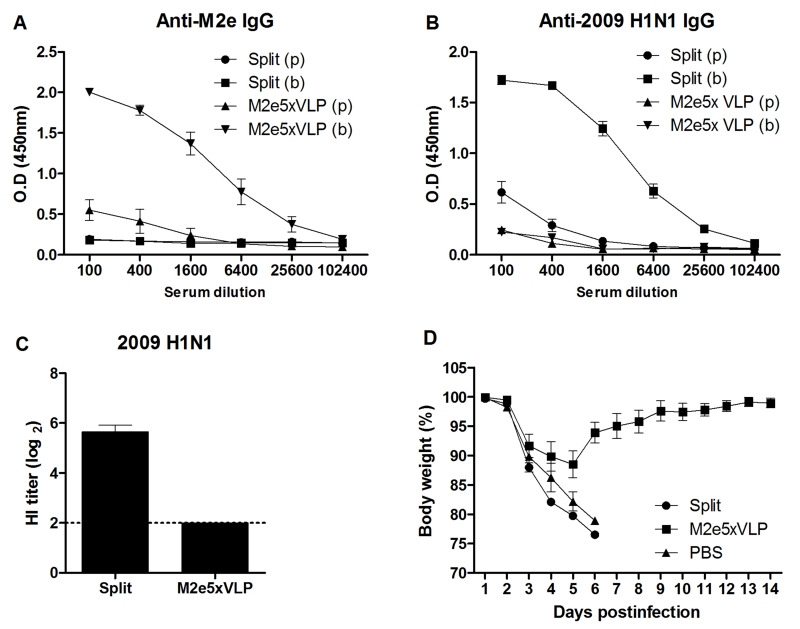

As seen in the 2009 pandemic and outbreaks of avian influenza viruses, current vaccination is not prepared for preventing a future new strain with different antigenicity. As a vaccination strategy toward a pandemic preparedness effort, we evaluated the immunogenicity of M2e5x VLP and split vaccines. At 21 days after boost vaccination of mice with M2e5x VLP or split vaccine, mice developed M2e-specific (Fig. 1A) or virus-specific (Fig. 1B) antibodies, respectively. As an indicator of virus neutralizing activity, the mice immunized with split vaccine showed homologous hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titers up to 5.6 ± 0.3 of log2 (Fig. 1C). However, sera from M2e5x VLP-immunized mice showed no HI activity against 2009 H1N1 virus.

Fig. 1. M2e5x VLP is superior to split vaccine in conferring heterosubtypic protection.

BALB/c mice (n = 10 per group) were intramuscularly immunized with M2e5x VLP or split vaccine. Blood samples were collected at 3 weeks after immunization, respectively. IgG antibodies specific for M2e peptide (A) or inactivated 2009 H1N1 virus (B) were measured in prime (p) and boost (b) immune sera. (C) Hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titers. HI titers were determined by standard methods using 4 HA units of inactivated A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus and 1% chicken erythrocyte suspension. (D) Superior cross protection by M2e5x VLP. Groups of mice (n = 4 per group) were challenged with a 10 LD50 of A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (rgH5N1) virus at 4 weeks after boost immunization. Body weight changes were monitored for 14 days. Data are representative of three independent experiments that are highly reproducible. Error bars indicates mean ± SEM.

To compare heterosubtypic cross protective efficacy, immune mice were challenged with a reassortant A/H5N1 virus (Fig. 1D). The 2009 H1N1 split vaccine group showed severe weight loss and did not survive lethal infection with A/H5N1 virus. In contrast, M2e5x VLP immune mice were 100% protected despite moderate weight loss. These results suggest that M2e5x VLP can confer superior protection compared to split vaccine when a new pandemic strain emerges.

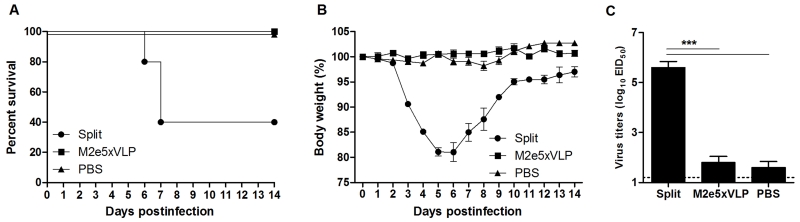

Split vaccine is effective in conferring homologous protection

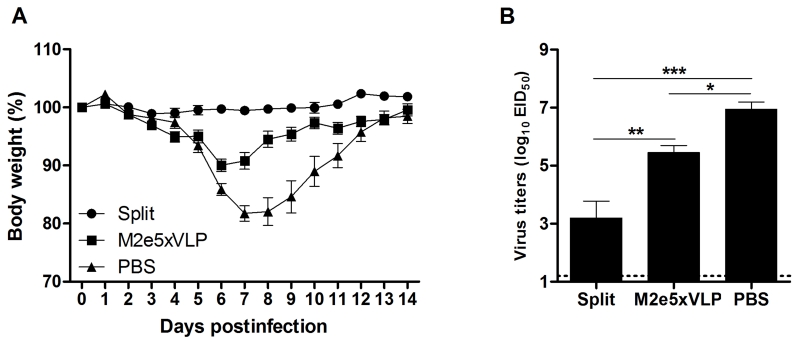

The efficacy of split vaccine immunization was tested by challenging immune mice with a sub-lethal dose of 2009 H1N1 homologous virus (Fig. 2). Mice immunized with homologous split vaccine did not develop any clinical signs following infection and did not display a loss in body weight (Fig. 2A). Mice vaccinated with M2e5x VLP showed a slight loss (approximately 10%) in body weight and then rapidly recovered to normal weight. In contrast, PBS mock control mice developed severe body weight loss from days 5 to 7 post-infection (p.i.). and showed a significant delay in recovery. To better assess the protective efficacy, lung viral titers were determined (Fig. 2B). The development of clinical signs correlated with virus titers in the lungs at day 4 p.i.. The lung viral titers of the split-vaccinated group (3.2 ± 0.6 Log10EID50/ml) were significantly lower than those in the PBS control group (6.9 ± 0.3 Log10EID50/ml, p < 0.001) and the M2e5x VLP-immunized group (5.4 ± 0.3 Log10EID50/ml, p < 0.01). Moreover, the lung viral titers of the M2e5x VLP-immunized group were approximately 31.6-fold lower than those in the PBS control group, which is statistically significant (p < 0.05). These results indicate that split vaccine is effective in inducing immunity to homologous IAV vaccine strain.

Fig. 2. Split vaccine is effective in conferring homologous protection.

Groups of mice (n = 10 per group) were challenged with a 0.8 LD50 of A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus at 4 weeks after boost vaccination. Body weight (A) was monitored for 14 days. Lung viral titers (B) were determined at 4 day p.i. by an egg infection assay (n = 4 per group). Data are representative of two independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM. Statistically significance was determined by 1-way ANOVA.

M2e5x VLP does not hamper the induction of virus-specific CD8 T cell responses in lungs after primary infection

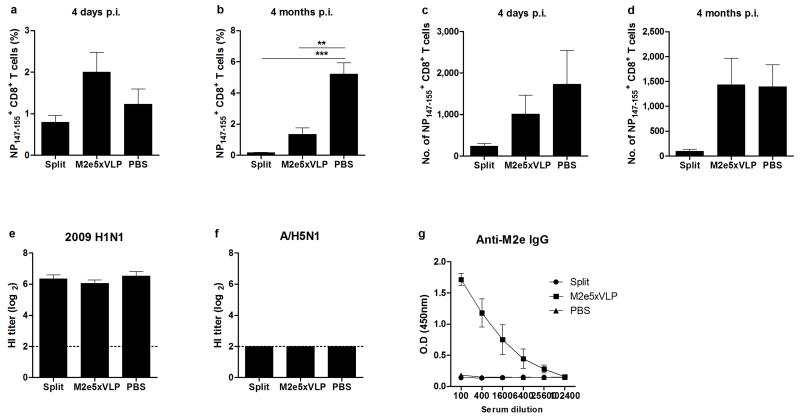

We hypothesized that M2e5x VLP immunization would be more effective in inducing T cell responses to conserved NP epitopes than split vaccination during homologous primary infection. At 4 days and 4 months after infection with 2009 H1N1 virus, the frequency of CD8+ T cells specific for the NP147-155 epitope was assessed by staining lung cells with a tetramer specific for this epitope, respectively. At 4 days p.i., the frequency of NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cells in the lungs of split, M2e5x VLP, and PBS-immunized mice were 0.80 ± 0.16, 2.00 ± 0.48, and 1.23 ± 0.36, respectively (Fig. 3A). At an early time post primary infection, M2e5x VLP immune mice showed approximately 2-fold higher levels of percentages in NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cell responses in lungs than split vaccine immune mice. The cellularity of NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cells in lungs was detected at high levels in the PBS group and M2e5x VLP-immunized group than the split vaccine immune group (Fig. 3C). At 4 months p.i., the frequency (Fig. 3B) and cellularity (Fig. 3D) of NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cells in the lungs of split-vaccinated mice were reduced to a background level. In contrast, the mean percentages of NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cells in the lungs from M2e5x VLP-vaccinated mice were higher than the split vaccine group and maintained for over 4 months (Figs. 3A and 3B) prior to the secondary infection (Fig. 5). The PBS control mice showed an increase in the percentages of NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cells at a later time point compared to that at day 4 p.i.. Importantly, the cellularity of NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cells in the M2e5x VLP group was maintained at high levels comparable to those of the PBS control group at early and late time points (Figs. 3C and 3D). Therefore, these results suggest that M2e immunity allowing limited replication without severe disease during primary infection is effective in inducing virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses.

Fig. 3. M2e5x VLP is effective in mediating the induction of NP-specific CD8+ T cells after primary infection.

(A-D) The percentages (A, B) or cellularity (C, D) of CD8+ T cells are presented after staining of lung cells with NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramer. The cell numbers are expressed as of per tissue. The lung cells are obtained at 4 days (A, C) and 4 months (B, D) after infection with A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) virus (n = 4 per group). (E-F) HI titers were determined in serum samples collected from the mice at 4 months after infection with 2009 H1N1 virus (n = 10 per group). HI titers were determined by standard methods using 4 HA units of inactivated 2009 H1N1 virus (E) or A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (rgH5N1) virus (F). (G) Anti-M2e IgG antibodies in sera at 4 months after infection with 2009 H1N1 virus. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM. Statistically significance was determined by 1-way ANOVA.

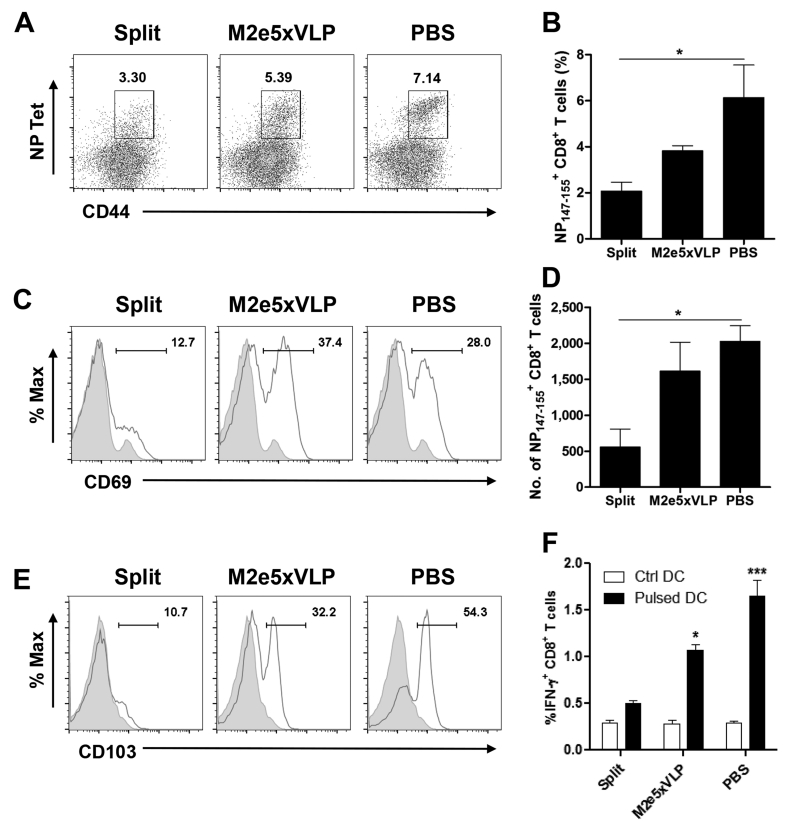

Fig. 5. Mice with M2e5x VLP vaccination further increase NP-specific lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells during secondary heterosubtypic IAV infection.

Groups of mice (n = 3 per group) were challenged with a 10 LD50 of A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (rgH5N1) virus at 4 months after first infection. Lung cells were isolated from mice at day 4 p.i.. (A) NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramer+-specific CD8+ T cells in lungs. Flow cytometric analysis showing lung CD8+ T cells that are stained with NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramers after gating total lung CD8+ T cells. (B) Percentages of NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramer+ CD8+ T cells in the total CD8+ T cells. (C) Representative histograms showing CD69 expression on gated NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramer+ CD8+ T cells in the lung. NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramer+ lung CD8+ T cells were gated first to determine CD69 expression. (D) The cellularity of NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramer+ CD8+ T cells in the total CD8+ T cells is expressed as the number per lung. (E) Representative histograms showing CD103 expression on gated NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramer+ CD8+ T cells in the lung. NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramer+ lung CD8+ T cells were gated first to determine CD103 expression. (F) Percentages of IFN-γ expression in total lung CD8+ T cells after in vitro stimulation with NP147-155 peptide-pulsed BMDCs. Lung cells were cocultured with peptide-pursed BMDCs with the ratio of 1:10 for BMDC to lung cells. After 5 days, the cells were washed and IFN-γ expressing T cells were assessed by flow cytometry. After gating CD8+ T cells, IFN-γ positive events were evaluated by flow cytometry of intracellularly stained cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM. Statistically significance was determined by 1-way ANOVA. Ctrl DC, control dendritic cells; Pulsed-DC, peptide-pulsed dendritic cells.

HI assay is the standard measurement for the presence of neutralizing antibodies. At 4 months after infection with 2009 H1N1, all vaccinated or PBS control mice showed high HI titers against 2009 H1N1 virus (Fig. 3E) but no HI activity against heterosubtypic A/H5N1 virus (Fig. 3F). The M2e5x VLP group showed high levels of M2e-specific antibodies at 5 months after boost vaccination but the PBS control or split vaccine group did not (Fig. 3E), even if they were infected with 2009 H1N1 virus, indicating that split vaccine immunization even after subsequent viral infection is not still effective in inducing M2e-specific antibodies.

M2e5x VLP does not prevent establishing secondary heterosubtypic immunity after primary infection

M2e5x VLP immune mice maintained M2e antibodies and NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cell responses even at 4 months after primary infection. We tested whether non-HA immunity would confer protection against an unexpected future virus. Groups of mice were challenged with a 10 LD50 of A/H5N1 virus as a second follow-up infection after 4 months. The split-vaccinated group showed ~22% body weight loss and 40% survival rate, and a significant delay in recovery of body weight in surviving mice (Figs. 4A and 4B). By contrast, all mice immunized with M2e5x VLP did not show weight loss, resulting in 100% protection.

Fig. 4. Mice with M2e5x VLP immunization are completely protected against secondary heterosubtypic influenza virus.

Groups of mice (n = 10 per group) were challenged with a 10 LD50 of A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (rgH5N1) virus at 4 months after first infection. Survival rate (A) and body weight changes (B) were monitored for 14 days. (C) Lung viral titers were determined at 4 day p.i. by an egg infection assay (n = 4 per group). Data are representative of two independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM. Statistically significance was determined by 1-way ANOVA.

The M2e5x VLP-immunized group lowered lung viral loads by 10,000-fold close to a detection limit (1.8 ± 0.2 Log10EID50/ml, p < 0.001, Fig, 4C) similar to the PBS mock control group that showed severe weight loss during primary infection. The split-vaccinated group could not control lung viral replication displaying high titers (5.6 ± 0.2 Log10EID50/ml). Thus, these results provide evidence that M2e5x VLP immunization followed by primary infection can be superior to split vaccine in equipping the host with heterosubtypic immunity against a novel influenza strain in future.

Lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells secreting IFN-γ have a correlation with subsequent heterosubtypic immunity

Equivalent protection between the M2e5x VLP and PBS mock control groups suggested a possible role of T cells in the heterosubtypic immunity. At 4 days after secondary infection of H1N1-exposed mice with A/H5N1, CD8+ T cells specific for the NP147-155 epitope in the lung were determined by tetramer and intracellular IFN-γ staining after stimulation with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. The mean percentages (Figs. 5A and 5B) and cellularity (Fig. 5D) of NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cells were observed at significantly higher levels in the lungs from the PBS control group than those from the split-vaccinated group. Moreover, the frequency of NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cells in lungs from M2e5x VLP-vaccinated mice were increased and higher than those from split-vaccinated mice, implicating the presence of pre-existing lung memory T cells after M2e5x VLP vaccination and primary infection. The early T-cell activation marker CD69 was upregulated exclusively in the NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cell subset in the lungs from M2e5xVLP immune or PBS control mice, whereas the NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cell subset observed at a low level from split-vaccine mice was predominantly CD69-negative (Fig. 5C). Moreover, the integrin CD103, which binds E-cadherin on epithelial cells, was also upregulated on NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cells in the lungs from M2e5x VLP immune or PBS control mice, but not from split-vaccinated mice (Fig. 5E). Interestingly, NP147-155-specific IFN-γ secretion was detected at a significantly higher level by CD8+ T cells in the lungs from M2e5x VLP immune mice (p < 0.05, Fig. 5E) or PBS control mice (p < 0.001) than that from split vaccine immune mice after in vitro stimulation with NP147-155 peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. These results suggest that generation of lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells secreting IFN-γ in the vaccination and infection regimen plays a significant role in conferring subsequent heterosubtypic immunity.

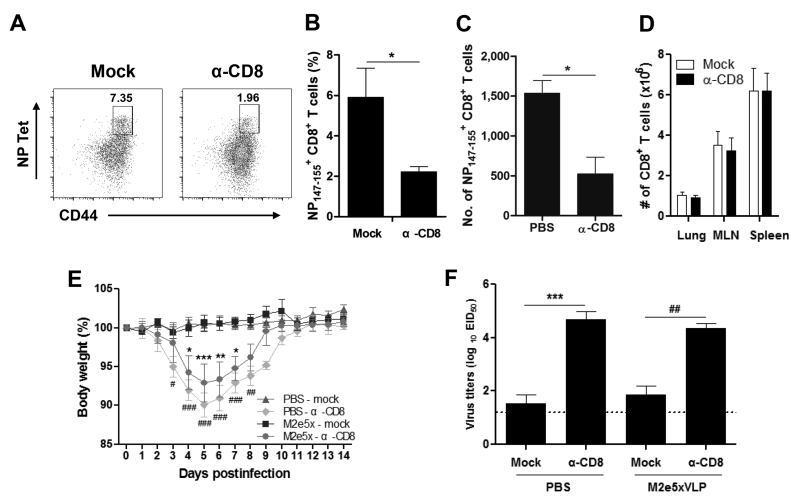

Virus-specific lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells play a critical role in heterosubtypic immunity

We determined whether influenza virus-specific CD8+ TRM cells in lungs primed during first infection were required for protection against subsequent heterosubtypic IAV infection. It was reported that resident and circulatory T cells in the lung following influenza infection could be differentiated using an intravenous antibody labeling approach (38). First, the condition of selectively depleting lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells but not systemic CD8+ T cells was optimized with CD8+ T cell depleting antibodies at a low dose via intranasal administration. Mice were challenged with a sub-lethal dose of 2009 H1N1 and then intranasally treated with a pre-determined low amount of anti-CD8 antibodies. Four days following anti-CD8 antibody treatment, total CD8+ T cells in the lungs, mediastinal lymph node and spleens were observed to be maintained at similar levels between the anti-CD8 antibody treated and untreated mock control mice (Fig. 6D). In contrast, the frequency and cellularity of NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cells were significantly reduced by 3-4 folds in the lungs of anti-CD8-treated mice compared with PBS-treated control mice (Figs. 6A, 6B and 6C). Therefore, intranasal administration of a low amount of anti-CD8 mAb could be used as a tool to deplete preferentially lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells without significantly affecting the circulating systemic CD8+ T cells.

Fig. 6. Lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells play a critical role in conferring heterosubtypic immunity.

Groups of mice were intranasally treated with PBS or anti-CD8 antibody at 4 months after primary infection. (A) Selective depletion of lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells after intranasal treatment with CD8 depleting antibodies at a low dose. A representative flow cytometry profile shows lung CD8+ TRM cells that are stained with NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramers. Lung CD8+ TRM cells were analyzed by flow cytometry at 4 days after mock (left) or anti-CD8 antibody (right) treatment (n = 3 per group). Results are shown for one of three independent and reproducible experiments. (B) Percentage of NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramer+ CD8+ T cells in the total lung cells. (C) The cellularity of NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramer+ CD8+ T cells in the total lung cells is expressed as the number per lung. (D) The cellularity of total CD8+ T cells in lungs, mediastinal lymph nodes, and spleens. The cell numbers are expressed as of per tissue. (E) Effects of lung-resident CD8+ T cell depletion on the efficacy of heterosubtypic immunity. Groups of mice (n = 4 per group) were challenged with a 10 LD50 of A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (rgH5N1) virus at 4 days after CD8 depleting antibody treatment intranasally and body weight changes were monitored for 14 days. (F) Mice with CD8 antibody intranasal treatment fail to clear lung viral loads. Lung viral titers were determined at 4 day p.i. by an egg infection assay (n = 3 per group). Data are representative of two independent and reproducible experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM. Statistically significance was determined by 1-way or 2-way ANOVA where appropriate. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001) compared with the results in the PBS control group. Pounds indicate significant differences (#p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001) compared with the results in the M2e5x group. MLN, mediastinal lymph node.

Next, M2e5x immune mice and PBS control mice both of which experienced primary infection with 2009 pandemic virus were challenged with a 10 LD50 of A/H5N1 virus after selective depletion of lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells. Mice that were depleted of CD8+ TRM cells in lungs suffered from significant body weight loss whereas mock-treated mice did not show body weight loss (Fig. 6E). M2e5x immune mice that were treated with CD8+ T-cell-depleting antibodies showed a moderate loss of body weight (~7%) and then fully recovered. Meanwhile, PBS control mice with CD8+ T cell-depleting antibodies showed a more substantial body weight loss over 10% as well as a delay in recovery of weight loss probably due to the lack of M2e antibodies. Moreover, the lung viral titers of the M2e5x immune (4.4 ± 0.3 Log10EID50/ml, p < 0.01) or PBS control (4.7 ± 0.5 Log10EID50/ml, p < 0.001) groups that were treated anti-CD8 antibodies were significantly higher than those in the mock-treated groups (Fig. 6F). These results provide strong evidence that virus-specific TRM cells in the lung play an essential role in conferring heterosubtypic immunity.

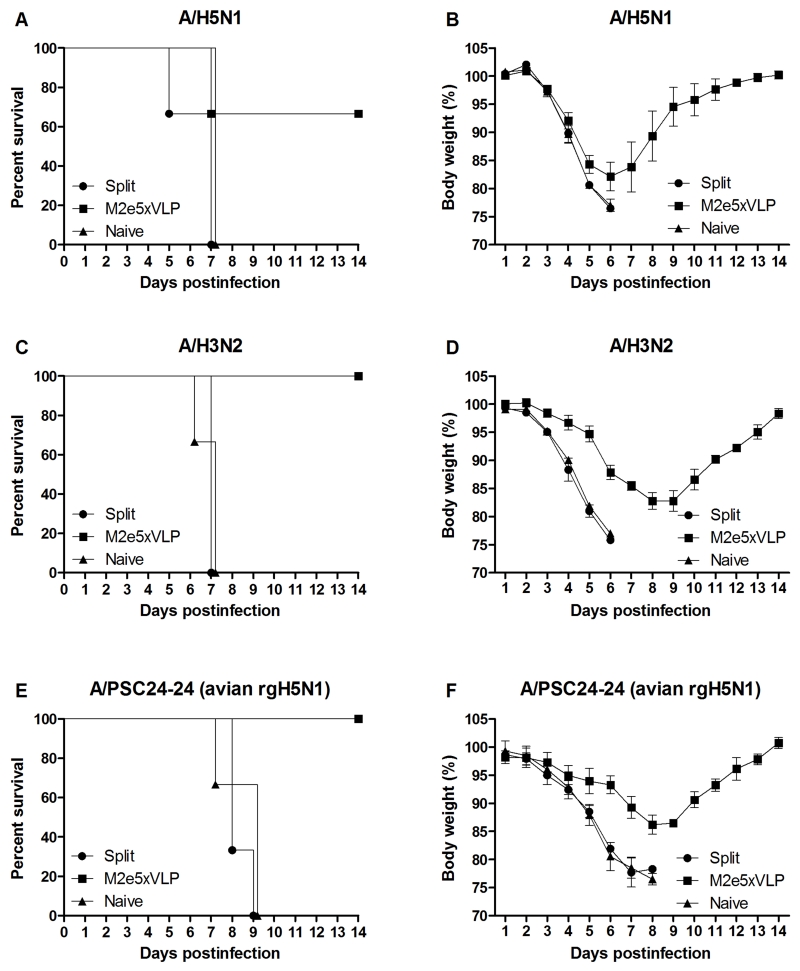

M2e-specific antibodies also contribute to heterosubtypic immunity

M2e5x VLP immune mice were found to be better protected against secondary heterosubtypic virus challenge in a condition with depletion of lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells than the PBS control group (Fig. 6). Thus, we further evaluated whether M2e5x immune sera would contribute to cross-protection against different subtypes of influenza A viruses. Naive mice were infected with a lethal dose of different strains of IAVs mixed with immune sera. Sera from naïve or 2009 H1N1-exposed split-vaccinated mice did not provide any protection to naïve mice (Fig. 7). In contrast, immune sera from mice vaccinated with M2e5x VLP conferred 67% protection to naïve mice that were infected with A/H5N1 (Fig. 7A). Moreover, M2e5x VLP-immune sera granted 100% protection to naïve mice that were infected with A/H3N2 (Fig. 7C) or A/PSC24-24 (avian rgH5N1) with an avian type M2e (Fig. 7E). Moderate levels of morbidity (14-17% weight loss) depending on the virus strain used for infection were observed in protected mice. These results support that M2e-specific antibodies generated following vaccination with M2e5x VLP but not immune sera from split vaccination contribute to cross protection during subsequent heterosubtypic lethal infection.

Fig. 7. Sera of M2e5x VLP immune mice contribute to conferring cross-protection.

Mice (n = 3 per group) were intranasally infected with a lethal dose of reassortant A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (A/H5N1) (A, B), A/Philippines/2/82 (A/H3N2) (C, D), and reassortant A/Mandarin Duck/Korea/PSC24-24/2010 (avian rgH5N1) (E, F) virus mixed with 2-fold diluted immune sera or naive sera. Immune sera collected from vaccinated mice at 4 months after challenge with 2009 H1N1 virus. Survival rates (A, C, E) and body weight changes (B, D, F) were monitored for 14 days. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments. Data represent mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Current strategy of seasonal influenza vaccination is based on immunity to HA, mainly aiming to induce vaccine strain-specific neutralizing antibodies. When the prediction of a circulating strain in the next season is well matched with a chosen vaccine strain, the efficacy is sufficiently high. However, this strategy has a major drawback of being unable to protect against a new and/or unanticipated strain. Wild birds serve as a natural reservoir that presumably contains numerous possible combinations of HA and NA subtypes, consistently providing a source of introducing new strains into poultry. In addition, pigs are known to play a role as mixing vessels in generating diverse new reassortants from avian and human influenza viruses (39). These unavoidable natural reservoirs make it extreme difficult to predict a matching vaccine strain and what strain might be a next pandemic. The emergence of swine-origin 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus provides a good example of this major vulnerability of the current vaccination strategy. Hence, this study has focused on exploring a new paradigm of vaccination and providing mechanistic insight into surmounting these problems by inducing humoral and cellular immunity to highly conserved antigenic targets.

We investigated two different outcomes of protection after first exposure to homologous or heterosubtypic virus in the context of split vaccine. In the scenario of homologous challenge infection, HA-based split vaccine was superior to M2e5x VLP probably due to its induction of virus neutralizing antibodies thus demonstrating that, indeed, the current strategy of influenza vaccination is highly effective if a circulating virus is matched with the vaccine strain. Also, this suggests that a strategy of inducing neutralizing antibodies is more effective than non-neutralizing immunity such as M2e5x VLP vaccination. These results are consistent with previous studies reporting that M2e conjugate protein vaccines with adjuvants were shown to confer survival protection but not effective in preventing weight loss (40-42). Encouragingly, M2e5x VLP vaccination in the absence of adjuvants was effective in preventing weight loss as well as broadening cross protection against H1, H3, and H5 subtype IAVs (22, 43). Thus, as shown herein, it is highly significant that a universal vaccination strategy can provide superior cross protection to current vaccines in the scenario of when a first infecting virus is antigenically different from a vaccine strain. Protective mechanisms by M2e immunity include anti-M2e specific IgG antibodies, Fc γ receptors, natural killer cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, alveolar macrophages, and dendritic cells (34, 37, 44-45).

A major drawback of seasonal vaccine strategy is that current vaccination regimes are not prepared for preventing a future pandemic outbreak. After primary protection against homologous virus as designed in the current vaccination strategy, split vaccination was not effective at all when a subsequent heterosubtypic virus was exposed 4 months later as evidenced by severe weight loss and low survival rates. Therefore, strain-specific immunity might make the host greatly vulnerable to severe infection with a new variant virus in future. As demonstrated in this study, a possible mechanism is that immunization with split vaccine is unable to induce cross-protective CD8+ TRM cells in lungs during primary protection against homologous strain. Therefore, split vaccine immune mice were not protected against a subsequent heterosubtypic H5N1 viral infection. To overcome these problems, our strategy was that vaccination with M2e5x VLP would protect from severe disease of heterosubtypic primary infection as well as equip the host with cross protective immunity to a subsequent pandemic potential strain. T cells can recognize conserved epitopes in the internal proteins of IAVs, which is considered to be a major mediator providing heterosubtypic immunity by viral infection (7, 46-47).

Phenotypes of T cells that are responsible for conferring heterosubtypic immunity are not well understood yet in particular after vaccination and infections. In this study, we observed that M2e5x VLP immune mice maintained a substantial level of NP147-155-specific CD8+ T cells for over 4 months after primary infection but not split vaccine immune mice, indicating that a certain level of viral replication is required. To obtain mechanistic insights into heterosubtypic immunity, phenotypes of NP147-155-specific CD8 T+ cells were further determined during secondary infection using CD103 (αE integrin) and CD69, molecules traditionally associated with adhesion within epithelial layers and recent activation (48-50). The expression of CD69 and CD103 as phenotypic markers of TRM cells in lungs was highly upregulated on NP-specific CD8+ T cells in the lung from M2e5x VLP-immune mice but not from split vaccinated mice. Intranasal treatment with CD8+ depleting antibodies at a low dose effectively depleted lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells but not the circulating systemic CD8+ T cells. Interestingly, we found that mice depleted of CD8+ TRM cells displayed more body weight loss and higher viral loads in lungs compared with mock-treated mice. Consistent with our results, it was reported that a circulating population of memory T cells was not sufficient for heterosubtypic immunity (51-52). Recently, Steinert et al. reported that the number of TRM cells is underestimated by standard immunologic assays due to the limitation in the complete isolation of resident memory T cells from non-lymphoid tissues and the fact that some TRM cells showed CD69− or CD103− phenotypes (53). Thus, findings in this study provide convincing evidence that pulmonary NP147-155-specific resident memory CD8+ TRM cells play a critical role in conferring heterosubtypic immunity, even though they might not fully represent total lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells. Interestingly, the PBS control group that was treated with CD8 depleting antibody showed more severe weight loss and higher viral loads during secondary heterosubtypic infection compared to the M2e5x VLP immune mice, supporting the roles of M2e antibodies. M2e5x VLP immune sera were found to grant higher protection to naïve mice against a lethal dose of different H3 and H5 subtypes of IAV. Surprisingly, we found that lung viral clearance in M2e5x VLP immune mice during secondary heterosubtypic infection was highly effective, completely preventing weight loss. Thus, the results in this study support that M2e-specific humoral immune responses by M2e5x VLP immunization are contributing to cross protection during primary infection as well as during secondary infection in addition to NP-specific CD8+ TRM cell responses.

M2e5x VLP was effective in preparing the host with establishing heterosubtypic immunity during primary infection without severe disease as well as in eliciting and maintaining lung-resident memory CD8+ T cell responses against a future pandemic virus. Despite broader cross protection by a non-neutralizing conserved targets-based vaccine strategy, weaker protection during primary infection diminishes clinical significance. Disease severity after this M2e-based vaccination strategy may not be attenuated or could be differentially attenuated in at-risk human populations. As an alternative option, supplementing M2e5x VLP to split vaccines was found to significantly improve the cross protective efficacy by preventing morbidity (weight loss) compared to either vaccine alone (45) M2e conserved epitope-supplemented HA split vaccination is expected to confer equivalent protection against seasonal influenza virus strains since vaccine strain-specific immunity was elicited by supplemented split vaccination in addition to the M2e immunity (45). However, long term secondary cross protection after supplemented vaccination and subsequent heterosubtypic infections remains to be determined. This approach of supplemented vaccination could be a clinically viable option, significantly relieving the public healthy burden of annually updating seasonal vaccines. Stockpiling cross protective vaccine such as M2e5x VLP for use during a sudden outbreak of a novel influenza virus can be another option until a strain-matched vaccine against the emerging virus was available. Therefore, universal epitope-based and/or supplemented vaccines conferring protection against circulating viruses as well as allowing heterosubtypic immunity could serve as a potential strategy to combat future pandemic.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the NIH Tetramer Core Facility (contract HHSN272201300006C) for provision of NP147-155 H-2Kd tetramers.

This work was supported by NIH/NIAID grants AI105170 (S.M.K.), AI119366 (S.M.K.), and AI093772 (S.M.K.).

References

- 1.Zambon M, Potter CW. Principles and practice of clinical virology. Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. Influenza. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webster RG, Laver WG. The origin of pandemic influenza. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;47:449–452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palese P. Influenza: old and new threats. Nat Med. 2004;10:S82–87. doi: 10.1038/nm1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC . 2009 H1N1 flu: international situation update. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garten RJ, Davis CT, Russell CA, Shu B, Lindstrom S, Balish A, Sessions WM, Xu X, Skepner E, Deyde V, Okomo-Adhiambo M, Gubareva L, Barnes J, Smith CB, Emery SL, Hillman MJ, Rivailler P, Smagala J, de Graaf M, Burke DF, Fouchier RA, Pappas C, Alpuche-Aranda CM, Lopez-Gatell H, Olivera H, Lopez I, Myers CA, Faix D, Blair PJ, Yu C, Keene KM, Dotson PD, Jr., Boxrud D, Sambol AR, Abid SH, St George K, Bannerman T, Moore AL, Stringer DJ, Blevins P, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Ginsberg M, Kriner P, Waterman S, Smole S, Guevara HF, Belongia EA, Clark PA, Beatrice ST, Donis R, Katz J, Finelli L, Bridges CB, Shaw M, Jernigan DB, Uyeki TM, Smith DJ, Klimov AI, Cox NJ. Antigenic and genetic characteristics of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses circulating in humans. Science. 2009;325:197–201. doi: 10.1126/science.1176225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grebe KM, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Heterosubtypic immunity to influenza A virus: where do we stand? Microbes Infect. 2008;10:1024–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreijtz JH, Bodewes R, van Amerongen G, Kuiken T, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Rimmelzwaan GF. Primary influenza A virus infection induces cross-protective immunity against a lethal infection with a heterosubtypic virus strain in mice. Vaccine. 2007;25:612–620. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurie KL, Carolan LA, Middleton D, Lowther S, Kelso A, Barr IG. Multiple infections with seasonal influenza A virus induce cross-protective immunity against A(H1N1) pandemic influenza virus in a ferret model. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1011–1020. doi: 10.1086/656188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yetter RA, Barber WH, Small PA., Jr. Heterotypic immunity to influenza in ferrets. Infect Immun. 1980;29:650–653. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.2.650-653.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowling BJ, Ng S, Ma ES, Cheng CK, Wai W, Fang VJ, Chan KH, Ip DK, Chiu SS, Peiris JS, Leung GM. Protective efficacy of seasonal influenza vaccination against seasonal and pandemic influenza virus infection during 2009 in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1370–1379. doi: 10.1086/657311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein SL. Prior H1N1 influenza infection and susceptibility of Cleveland Family Study participants during the H2N2 pandemic of 1957: an experiment of nature. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:49–53. doi: 10.1086/498980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCaw JM, McVernon J, McBryde ES, Mathews JD. Influenza: accounting for prior immunity. Science. 2009;325:1071. doi: 10.1126/science.325_1071a. author reply 1072-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rimmelzwaan GF, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD. Influenza virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes: a correlate of protection and a basis for vaccine development. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2007;18:529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodewes R, Kreijtz JH, Baas C, Geelhoed-Mieras MM, de Mutsert G, van Amerongen G, van den Brand JM, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Rimmelzwaan GF. Vaccination against human influenza A/H3N2 virus prevents the induction of heterosubtypic immunity against lethal infection with avian influenza A/H5N1 virus. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bodewes R, Kreijtz JH, Hillaire ML, Geelhoed-Mieras MM, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Rimmelzwaan GF. Vaccination with whole inactivated virus vaccine affects the induction of heterosubtypic immunity against influenza virus A/H5N1 and immunodominance of virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in mice. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:1743–1753. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.020784-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schotsaert M, Ysenbaert T, Neyt K, Ibanez LI, Bogaert P, Schepens B, Lambrecht BN, Fiers W, Saelens X. Natural and long-lasting cellular immune responses against influenza in the M2e-immune host. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:276–287. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito T, Gorman OT, Kawaoka Y, Bean WJ, Webster RG. Evolutionary analysis of the influenza A virus M gene with comparison of the M1 and M2 proteins. J Virol. 1991;65:5491–5498. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5491-5498.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zebedee SL, Lamb RA. Nucleotide sequences of influenza A virus RNA segment 7: a comparison of five isolates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:2870. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.7.2870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiers W, De Filette M, Birkett A, Neirynck S, Min Jou W. A "universal" human influenza A vaccine. Virus Res. 2004;103:173–176. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du L, Zhou Y, Jiang S. Research and development of universal influenza vaccines. Microbes Infect. 2010;12:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao G, Lin Y, Du L, Guan J, Sun S, Sui H, Kou Z, Chan CC, Guo Y, Jiang S, Zheng BJ, Zhou Y. An M2e-based multiple antigenic peptide vaccine protects mice from lethal challenge with divergent H5N1 influenza viruses. Virol J. 2010;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim MC, Song JM, O E, Kwon YM, Lee YJ, Compans RW, Kang SM. Virus-like particles containing multiple M2 extracellular domains confer improved cross-protection against various subtypes of influenza virus. Mol Ther. 2013;21:485–492. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song JM, Hossain J, Yoo DG, Lipatov AS, Davis CT, Quan FS, Chen LM, Hogan RJ, Donis RO, Compans RW, Kang SM. Protective immunity against H5N1 influenza virus by a single dose vaccination with virus-like particles. Virology. 2010;405:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quan FS, Compans RW, Nguyen HH, Kang SM. Induction of heterosubtypic immunity to influenza virus by intranasal immunization. Journal of virology. 2008;82:1350–1359. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01615-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song JM, Wang BZ, Park KM, Van Rooijen N, Quan FS, Kim MC, Jin HT, Pekosz A, Compans RW, Kang SM. Influenza virus-like particles containing M2 induce broadly cross protective immunity. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wakamiya N, Okuno Y, Sasao F, Ueda S, Yoshimatsu K, Naiki M, Kurimura T. Isolation and characterization of conglutinin as an influenza A virus inhibitor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;187:1270–1278. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90440-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dundon WG, De Benedictis P, Viale E, Capua I. Serologic evidence of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 infection in dogs, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:2019–2021. doi: 10.3201/eid1612.100514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee YN, Lee HJ, Lee DH, Kim JH, Park HM, Nahm SS, Lee JB, Park SY, Choi IS, Song CS. Severe canine influenza in dogs correlates with hyperchemokinemia and high viral load. Virology. 2011;417:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method for estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Epidemiol. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deliyannis G, Kedzierska K, Lau YF, Zeng W, Turner SJ, Jackson DC, Brown LE. Intranasal lipopeptide primes lung-resident memory CD8+ T cells for long-term pulmonary protection against influenza. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:770–778. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall HT, Petrovic J, Hoglund P. Reduced antigen concentration and costimulatory blockade increase IFN-gamma secretion in naive CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3091–3101. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massa C, Seliger B. Fast dendritic cells stimulated with alternative maturation mixtures induce polyfunctional and long-lasting activation of innate and adaptive effector cells with tumor-killing capabilities. J Immunol. 2013;190:3328–3337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mishra S, Losikoff PT, Self AA, Terry F, Ardito MT, Tassone R, Martin WD, De Groot AS, Gregory SH. Peptide-pulsed dendritic cells induce the hepatitis C viral epitope-specific responses of naive human T cells. Vaccine. 2014;32:3285–3292. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jegerlehner A, Schmitz N, Storni T, Bachmann MF. Influenza A vaccine based on the extracellular domain of M2: weak protection mediated via antibody-dependent NK cell activity. J Immunol. 2004;172:5598–5605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Treanor JJ, Tierney EL, Zebedee SL, Lamb RA, Murphy BR. Passively transferred monoclonal antibody to the M2 protein inhibits influenza A virus replication in mice. J Virol. 1990;64:1375–1377. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1375-1377.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mozdzanowska K, Maiese K, Furchner M, Gerhard W. Treatment of influenza virus-infected SCID mice with nonneutralizing antibodies specific for the transmembrane proteins matrix 2 and neuraminidase reduces the pulmonary virus titer but fails to clear the infection. Virology. 1999;254:138–146. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee YN, Lee YT, Kim MC, Hwang HS, Lee JS, Kim KH, Kang SM. Fc receptor is not required for inducing antibodies but plays a critical role in conferring protection after influenza M2 vaccination. Immunology. 2014;143:300–309. doi: 10.1111/imm.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turner DL, Bickham KL, Thome JJ, Kim CY, D’Ovidio F, Wherry EJ, Farber DL. Lung niches for the generation and maintenance of tissue-resident memory T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:501–510. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schultz U, Fitch WM, Ludwig S, Mandler J, Scholtissek C. Evolution of pig influenza viruses. Virology. 1991;183:61–73. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90118-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Filette M, Fiers W, Martens W, Birkett A, Ramne A, Lowenadler B, Lycke N, Jou WM, Saelens X. Improved design and intranasal delivery of an M2e-based human influenza A vaccine. Vaccine. 2006;24:6597–6601. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fan J, Liang X, Horton MS, Perry HC, Citron MP, Heidecker GJ, Fu TM, Joyce J, Przysiecki CT, Keller PM, Garsky VM, Ionescu R, Rippeon Y, Shi L, Chastain MA, Condra JH, Davies ME, Liao J, Emini EA, Shiver JW. Preclinical study of influenza virus A M2 peptide conjugate vaccines in mice, ferrets, and rhesus monkeys. Vaccine. 2004;22:2993–3003. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu TM, Grimm KM, Citron MP, Freed DC, Fan J, Keller PM, Shiver JW, Liang X, Joyce JG. Comparative immunogenicity evaluations of influenza A virus M2 peptide as recombinant virus like particle or conjugate vaccines in mice and monkeys. Vaccine. 2009;27:1440–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim MC, Lee JS, Kwon YM, O E, Lee YJ, Choi JG, Wang BZ, Compans RW, Kang SM. Multiple heterologous M2 extracellular domains presented on virus-like particles confer broader and stronger M2 immunity than live influenza A virus infection. Antiviral Res. 2013;99:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.El Bakkouri K, Descamps F, De Filette M, Smet A, Festjens E, Birkett A, Van Rooijen N, Verbeek S, Fiers W, Saelens X. Universal vaccine based on ectodomain of matrix protein 2 of influenza A: Fc receptors and alveolar macrophages mediate protection. J Immunol. 2011;186:1022–1031. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim MC, Lee YN, Ko EJ, Lee JS, Kwon YM, Hwang HS, Song JM, Song BM, Lee YJ, Choi JG, Kang HM, Quan FS, Compans RW, Kang SM. Supplementation of influenza split vaccines with conserved M2 ectodomains overcomes strain specificity and provides long-term cross protection. Mol Ther. 2014;22:1364–1374. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kees U, Krammer PH. Most influenza A virus-specific memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes react with antigenic epitopes associated with internal virus determinants. J Exp Med. 1984;159:365–377. doi: 10.1084/jem.159.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McMichael AJ, Gotch FM, Noble GR, Beare PA. Cytotoxic T-cell immunity to influenza. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:13–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198307073090103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ziegler SF, Ramsdell F, Alderson MR. The activation antigen CD69. Stem Cells. 1994;12:456–465. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530120502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schon MP, Arya A, Murphy EA, Adams CM, Strauch UG, Agace WW, Marsal J, Donohue JP, Her H, Beier DR, Olson S, Lefrancois L, Brenner MB, Grusby MJ, Parker CM. Mucosal T lymphocyte numbers are selectively reduced in integrin alpha E (CD103)-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1999;162:6641–6649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee YT, Suarez-Ramirez JE, Wu T, Redman JM, Bouchard K, Hadley GA, Cauley LS. Environmental and antigen receptor-derived signals support sustained surveillance of the lungs by pathogen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Virol. 2011;85:4085–4094. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02493-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slutter B, Pewe LL, Kaech SM, Harty JT. Lung airway-surveilling CXCR3(hi) memory CD8(+) T cells are critical for protection against influenza A virus. Immunity. 2013;39:939–948. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ely KH, Cookenham T, Roberts AD, Woodland DL. Memory T cell populations in the lung airways are maintained by continual recruitment. J Immunol. 2006;176:537–543. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steinert EM, Schenkel JM, Fraser KA, Beura LK, Manlove LS, Igyarto BZ, Southern PJ, Masopust D. Quantifying Memory CD8 T Cells Reveals Regionalization of Immunosurveillance. Cell. 2015;161:737–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]