Abstract

The ascomycete family Nectriaceae (Hypocreales) includes numerous important plant and human pathogens, as well as several species used extensively in industrial and commercial applications as biodegraders and biocontrol agents. Members of the family are unified by phenotypic characters such as uniloculate ascomata that are yellow, orange-red to purple, and with phialidic asexual morphs. The generic concepts in Nectriaceae are poorly defined, since DNA sequence data have not been available for many of these genera. To address this issue we performed a multi-gene phylogenetic analysis using partial sequences for the 28S large subunit (LSU) nrDNA, the internal transcribed spacer region and intervening 5.8S nrRNA gene (ITS), the large subunit of the ATP citrate lyase (acl1), the RNA polymerase II largest subunit (rpb1), RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (rpb2), α-actin (act), β-tubulin (tub2), calmodulin (cmdA), histone H3 (his3), and translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1) gene regions for available type and authentic strains representing known genera in Nectriaceae, including several genera for which no sequence data were previously available. Supported by morphological observations, the data resolved 47 genera in the Nectriaceae. We re-evaluated the status of several genera, which resulted in the introduction of six new genera to accommodate species that were initially classified based solely on morphological characters. Several generic names are proposed for synonymy based on the abolishment of dual nomenclature. Additionally, a new family is introduced for two genera that were previously accommodated in the Nectriaceae.

Key words: Generic concepts, Nectriaceae, Phylogeny, Taxonomy

Taxonomic novelties: New family: Tilachlidiaceae L. Lombard & Crous

New genera: Aquanectria L. Lombard & Crous; Bisifusarium L. Lombard, Crous & W. Gams; Coccinonectria L. Lombard & Crous; Paracremonium L. Lombard & Crous; Rectifusarium L. Lombard, Crous & W. Gams; Xenoacremonium L. Lombard & Crous

New species: Mariannaea humicola L. Lombard & Crous, Neocosmospora rubicola L. Lombard & Crous, Paracremonium inflatum L. Lombard & Crous, P. contagium L. Lombard & Crous, Pseudonectria foliicola L. Lombard & Crous, Rectifusarium robinianum L. Lombard & Crous, Xenoacremonium falcatus L. Lombard & Crous, Xenogliocladiopsis cypellocarpa L. Lombard & Crous

New combinations: Aquanectria penicillioides (Ingold) L. Lombard & Crous; A. submerse (H.J. Huds.) L. Lombard & Crous; Bisifusarium biseptatum (Schroers, Summerbell & O'Donnell) L. Lombard & Crous; B. delphinoides (Schroers, Summerbell, O'Donnell & Lampr.) L. Lombard & Crous; B. dimerum (Penz.) L. Lombard & Crous; B. domesticum (Fr.) L. Lombard & Crous; B. lunatum (Ellis & Everh.) L. Lombard & Crous; B. nectrioides (Wollenw.) L. Lombard & Crous; B. penzigii (Schroers, Summerbell & O'Donnell) L. Lombard & Crous; Calonectria candelabra (Viégas) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; C. cylindrospora (Ellis & Everh.) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; Clonostachys apocyni (Peck) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; C. aurantia (Penz. & Sacc.) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; C. blumenaviae (Rehm) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; C. gibberosa (Schroers) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; C. manihotis (Rick) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; C. parva (Schroers) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; C. tonduzii (Speg.) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; C. tornata (Höhn.) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; Coccinonectria pachysandricola (B.O. Dodge) L. Lombard & Crous; C. rusci (Lechat, Gardiennet & J. Fourn.) L. Lombard & Crous; Hydropisphaera fusigera (Berk. & Broome) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; Ilyonectria destructans (Zinssm.) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; I. macroconidialis (Brayford & Samuels) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous, Mariannaea catenulatae (Samuels) L. Lombard & Crous; Nectriopsis rexiana (Sacc.) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; Neocosmospora ambrosia (Gadd & Loos) L. Lombard & Crous; N. falciformis (Carrión) L. Lombard & Crous; N. illudens (Berk.) L. Lombard & Crous; N. ipomoeae (Halst.) L. Lombard & Crous; N. monilifera (Berk. & Broome) L. Lombard & Crous; N. phaseoli (Burkh.) L. Lombard & Crous; N. plagianthi (Dingley) L. Lombard & Crous; N. ramosa (Bat. & H. Maia) L. Lombard & Crous; N. solani (Mart.) L. Lombard & Crous; N. termitum (Höhn.) L. Lombard & Crous; N. tucumaniae (T. Aoki, O'Donnell, Yos. Homma & Lattanzi) L. Lombard & Crous; N. virguliformis (O'Donnell & T. Aoki) L. Lombard & Crous; Neonectria candida (Ehrenb.) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; Penicillifer diparietisporus (J.H. Miller, Giddens & A.A. Foster) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; Rectifusarium ventricosum (Appel & Wollenw.) L. Lombard & Crous; Sarcopodium flavolanatum (Berk. & Broome) L. Lombard & Crous; S. mammiforme (Chardón) L. Lombard & Crous; S. oblongisporum (Y. Nong & W.Y. Zhuang) L. Lombard & Crous; S. raripilum (Penz. & Sacc.) L. Lombard & Crous; Sphaerostilbella penicillioides (Corda) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; S. aurifila (W.R. Gerard) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous; Volutella asiana (J. Luo, X.M. Zhang & W.Y. Zhuang) L. Lombard & Crous; Xenoacremonium recifei (Leão & Lôbo) L. Lombard & Crous

New name: Mariannaea pinicola L. Lombard & Crous

Typification: Epitypification (basionyms): Rectifusarium ventricosum Appel & Wollenw., Xenogliocladiopsis eucalyptorum Crous & W.B. Kendr.

Introduction

The order Hypocreales (Hypocreomycetidae, Sordariomycetes, Pezizomycotina, Ascomycota) includes approximately 2 700 fungal species from 240 genera, which are divided over eight families (Kirk et al., 2008, Crous et al., 2014), with some genera still classified as incertae sedis (Lumbsch & Huhndorf 2007). Members of this order are globally found in various environments and are of great importance to agriculture and medicine. They have been extensively exploited in industrial and commercial applications (Rossman 1996). These fungi are generally characterised by the production of lightly to brightly coloured, ostiolate, perithecial ascomata, containing unitunicate asci with hyaline ascospores; asexual morphs, the form most frequently encountered in nature, are moniliaceous and phialidic (Rogerson, 1970, Samuels and Seifert, 1987, Rossman, 1996, Rossman, 2000, Rossman et al., 1999). The taxonomic importance of these asexual morphs has only been recognised relatively recently (Rossman, 2000, Seifert and Samuels, 2000). The morphology of asexual forms is often crucial for the morphological identification of these fungi.

The family Nectriaceae is characterised by uniloculate ascomata that are white, yellow, orange-red or purple. These ascomata change colour in KOH, and are not immersed in a well-developed stroma. They are associated with phialidic asexual morphs producing amerosporous to phragmosporous conidia (Rossman et al., 1999, Rossman, 2000). This family includes around 55 genera that were originally based on asexual or sexual morphs. The genera include approximately 900 species (www.mycobank.org; www.indexfungorum.org). The majority of these species are soil-borne saprobes or weak to virulent, facultative or obligate plant pathogens, while some are facultatively fungicolous or insecticolous (Rossman et al., 1999, Rossman, 2000, Chaverri et al., 2011, Gräfenhan et al., 2011, Schroers et al., 2011). Several species have also been reported as important opportunistic pathogens of humans (Chang et al., 2006, Hoog et al., 2011, Guarro, 2013) while others produce mycotoxins of medical concern (Rossman 1996).

Prior to the advent of DNA sequencing studies, most sexual morph genera recognised in the Nectriaceae were placed in Nectria sensu lato (Rehner and Samuels, 1995, Rossman et al., 1999). The genus Nectria s. str., however, is restricted to the type species N. cinnabarina with tubercularia-like asexual morphs (Rossman, 2000, Hirooka et al., 2012). Recently, several studies have treated taxonomic concepts within Nectriaceae based on multi-gene phylogenetic inference (Lombard et al., 2010a, Lombard et al., 2010b, Lombard et al., 2012, Lombard et al., 2014a, Lombard et al., 2014b, Lombard and Crous, 2012, Chaverri et al., 2011, Gräfenhan et al., 2011, Schroers et al., 2011, Hirooka et al., 2012). In these studies, well-known and important plant and human pathogenic genera have been segregated into several new genera, with some older generic names resurrected (Chaverri et al., 2011, Gräfenhan et al., 2011, Schroers et al., 2011, Hirooka et al., 2011, Hirooka et al., 2012). This has resulted in debates (Geiser et al., 2013, O'Donnell et al., 2013, Aoki et al., 2014) about the prospects for continued use of certain well-known generic names, such as Fusarium, for species of agricultural and medical importance. Several genera traditionally classified in the Nectriaceae have been excluded from these studies. In the present study, the phylogenetic relationships of most of the genera known from culture and traditionally classified as Nectriaceae are evaluated based on DNA sequences of 10 loci. The goal is to provide a phylogenetic backbone for the family Nectriaceae. Nomenclatural changes due to the implementation of the new International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants (ICN; McNiell et al. 2012), are also considered in this study. The taxonomy of some genera is re-evaluated.

Materials and methods

Isolates

Fungal strains were obtained from the culture collection of the CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre (CBS), Utrecht, The Netherlands and the working collection of Pedro W. Crous housed at the CBS (Table 1).

Table 1.

Details of strains included in the phylogenetic analyses. GenBank accessions numbers in italics were newly generated in this study.

T Ex-type and ex-epitype cultures.

AR: Collection of A.Y. Rossman; ATCC: American Type Culture Collection, U.S.A.; BBA: Biologische Bundesanstalt für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, Berlin-Dahlem, Germany; CBS: CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Utrecht, The Netherlands; CMW: Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa; CCT: Colecao de Culturas Tropical, Fundacao Tropical de Pesquisas e Technologia “André Tosello”, Campinas-SP, Brazil; CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA; CLL: C. Lechat collection; CPC: P.W. Crous collection; CTR: C.T. Rogerson collection; DAOM: Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada National Mycological Herbarium, Canada; DSM: Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany; FMR: Facultad de Medicina, Reus, Tarragona, Spain; GJS: Gary J. Samuels collection; HJS: Hans-Josef Schroers collection; HKUCC: University of Hong Kong Culture Collection, Department of Ecology and Biodiversity, Hong Kong, China; IFO: Institute for Fermentation, Osaka, Yodogawa-ku, Osaka, Japan; IHEM: Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology-Mycology Laboratory, Brussels, Belguim; IMI: International Mycological Institute, CABI-Bioscience, Egham, Bakeham Lane, U.K.; IMUR: Institute of Mycology, University of Recife, Recife, Brazil; INIFAT: INIFAT Fungus Collection, Ministerio de Agricultura Habana; KAS: K.A. Seifert collection; MRC: National Research Institute for Nutritional Diseases, Tygerberg, South Africa; MUCL: Mycothèque de l’Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium; NBRC: NITE Biological Resource Center, Japan; NRRL: Agricultural Research Service Culture Collection, USA; PD: Collection of the Dutch National Plant Protection Organization (NPPO-NL), Wageningen, The Netherlands; PPRI: Plant Protection Research Institute, Pretoria, South Africa; PREM: National collection of Fungi, Agriculture Department, Pretoria, South Africa; QM: Quatermaster Research and Development Center, US Army, Natick, MA, USA; TG: T. Gräfenhan collection; UAMH: University of Alberta Mold Herbarium and Culture collection, Edmonton, Canada; UFV: Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Brazil.

acl1: large subunit of the ATP citrate lyase; act: α-actin; cmdA: calmodulin; his3: histone H3; ITS: the internal transcribed spacer region and intervening 5.8S nrRNA; LSU: 28S large subunit; rpb1: RNA polymerase II largest subunit; rpb2: RNA polymerase II second largest subunit; tef1: translation elongation factor 1-alpha; tub2: β-tubulin.

DNA isolation, amplification and analyses

Total genomic DNA was extracted from 7-d-old single-conidial cultures growing on 2 % (w/v) malt extract agar (MEA) using the method of Damm et al. (2008). Partial gene sequences were determined for the 28S large subunit (LSU) nrDNA, the internal transcribed spacer region and intervening 5.8S nrRNA gene (ITS), the large subunit of the ATP citrate lyase (acl1), the RNA polymerase II largest subunit (rpb1), RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (rpb2), β-tubulin (tub2), histone H3 (his3), translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1), calmodulin (cmdA) and α-actin (act) using the primers and PCR protocols listed in Table 2. Integrity of the sequences was ensured by sequencing the amplicons in both directions using the same primer pairs as were used for amplification. A consensus sequence for each locus was assembled in MEGA v. 6 (Tamura et al. 2013) and additional sequences were obtained from GenBank (Table 1). Subsequent alignments for each locus were generated in MAFFT v. 7 (Katoh & Standley 2013) and manually corrected where necessary. Phylogenetic congruency of the 10 loci was tested using a 70 % reciprocal bootstrap criterion (Mason-Gamer & Kellogg 1996).

Table 2.

Information on loci used in the phylogenetic analyses.

| Locus1 | Primers | Nucleotide substitution models | Included sites (# excluded sites) | Phylogenetically informative sites (%) | Uninformative polymorphic sites | Invariable sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| acl1 | acl1-230up, acl1-1220low (Gräfenhan et al. 2011) | HKY+I+G | 1620 (1103) | 1281 (79 %) | 235 | 104 |

| act | ACT-512F (Carbone & Kohn 1999), ACT1Rd (Groenewald et al. 2013) | GTR+I+G | 985 (476) | 551 (56 %) | 114 | 320 |

| cmdA | CAL-228F (Carbone & Kohn 1999), CAL2Rd (Groenewald et al. 2013) | GTR+I+G | 1209 (846) | 919 (76 %) | 103 | 187 |

| his3 | CYLH3F, CYLH3R (Crous et al. 2004b) | GTR+I+G | 788 (431) | 530 (67 %) | 97 | 161 |

| ITS | ITS5, ITS4 (White et al. 1990) | GTR+I+G | 1008 (572) | 619 (61 %) | 184 | 205 |

| LSU | LR0R (Rehner & Samuels 1994), LR5 (Vilgalys & Hester 1990) | GTR+I+G | 874 (6) | 316 (36 %) | 101 | 457 |

| rpb1 | RPB1-Ac, RPB1-Cr (Matheny et al. 2002) | GTR+I+G | 1489 (879) | 1264 (85 %) | 202 | 23 |

| rpb2 | RPB2-5F2, RPB2-7cR (O'Donnell et al. 2007) | GTR+I+G | 1366 (557) | 919 (67 %) | 399 | 48 |

| tef1 | EF1-728F (Carbone & Kohn 1999), EF2 (O'Donnell et al. 1998) | GTR+I+G | 1049 (850) | 854 (81 %) | 101 | 94 |

| tub2 | T1 (O'Donnell & Cigelnik 1997), CYLTUB1R (Crous et al. 2004b) | GTR+I+G | 898 (561) | 650 (72 %) | 72 | 176 |

acl1: large subunit of the ATP citrate lyase; act: α-actin; cmdA: calmodulin; his3: histone H3; ITS: the internal transcribed spacer region and intervening 5.8S nrRNA; LSU: 28S large subunit; rpb1: RNA polymerase II largest subunit; rpb2: RNA polymerase II second largest subunit; tef1: translation elongation factor 1-alpha; tub2: β-tubulin.

Phylogenetic analyses were based on Bayesian inference (BI) and Maximum Likelihood (ML). For both analyses, the evolutionary model for each partition was determined using MrModeltest (Nylander 2004) and incorporated into the analyses. For the BI analysis, the software package BEAST v. 8.0 (Drummond et al. 2012) was used. The phylogenetic relationships were estimated by performing six independent repetitions of 100 M generations each, with sampling at every 1 000th generation. The Yule speciation algorithm with GTR substitution model and a lognormal uncorrelated relaxed clock were selected for the data. LogCombiner v. 8.0 (from the BEAST package) was used to combine the outputs of six independent runs. The resulting trees were summarised using Tree Annotator v. 1.8.0 (from the BEAST package) using the maximum clade credibility option. FigTree v. 1.4 was used to visualise the final tree.

The ML analysis was performed using RAxML v. 8.0.9 (randomised accelerated (sic) maximum likelihood for high performance computing; Stamatakis 2014) through the CIPRES website (http://www.phylo.org) to obtain a second measure of branch support. The robustness of the analysis was evaluated by bootstrap support (BS) with the number of bootstrap replicates automatically determined by the software. All novel sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank (Table 1) and the alignment(s) and tree(s) in TreeBASE.

Morphology

For morphological characterisation, single-conidial isolates were grown on synthetic nutrient-poor agar (SNA, Nirenberg 1981) with sterile toothpicks, filter paper or carnation leaves placed on the surface of the agar. Alternatively, isolates were also plated onto potato dextrose agar (2 % w/v, PDA), oatmeal agar (OA) and malt extract agar (2 % w/v, MEA) (recipes in Crous et al. 2009) to induce sporulation when this failed on SNA. Plates were incubated at room temperature (22–25 °C) under ambient light conditions. Some isolates were incubated at 12 h / 12 h fluorescent light and darkness at 25 °C. Gross morphological characters of the asexual morphs were examined after 7–10 d by mounting fungal structures in clear lactic acid and measurements were made at ×1 000 magnification using a Zeiss Axioscope 2 microscope with differential interference contrast (DIC) illumination. The 95 % confidence levels were determined for the conidial measurements with extremes given in parentheses while only extremes are provided for other structures. Colony morphology was assessed using 7-d-old cultures on MEA, OA and/or PDA and the colour charts of Rayner (1970). All descriptions, illustrations and nomenclatural data were deposited in MycoBank (Crous et al. 2004a).

Results

Phylogenetic relationships

The multi-gene alignment length was 11 286 bases including gaps, for the 10 gene regions. The phylogenetic analyses included 206 ingroup taxa, with Stachybotrys chartarum (CBS 129.13) as an outgroup taxon. The congruence analyses detected one conflict for the placement of Rodentomyces reticulatus (CBS 128675) and Sarocladium kiliense (CBS 400.52), which could not be resolved without excluding both from the analyses. However, as these conflicts only involved the placement of single species, this was ignored and all partitions were combined following the argument of Cunningham (1997) that combining incongruent partitions could increase phylogenetic accuracy. All ambiguously aligned regions were excluded from the analyses (Table 2). The number of polymorphic and parsimony informative sites, and evolutionary model selected for each gene region are indicated in Table 2.

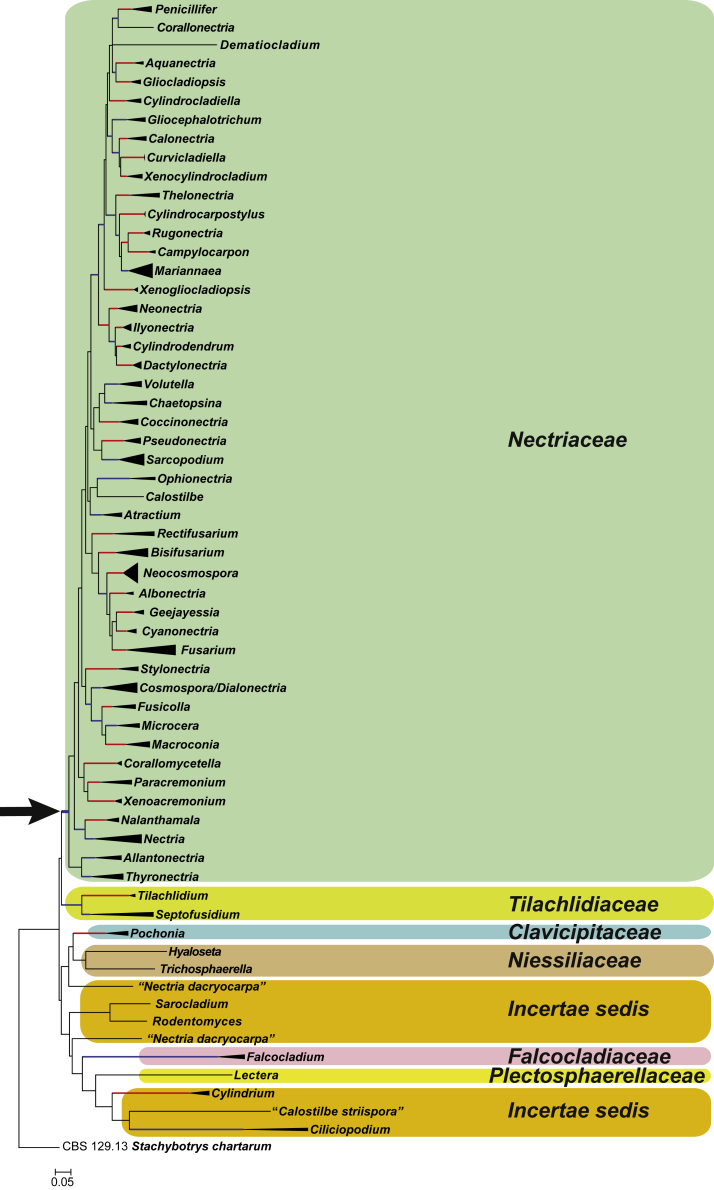

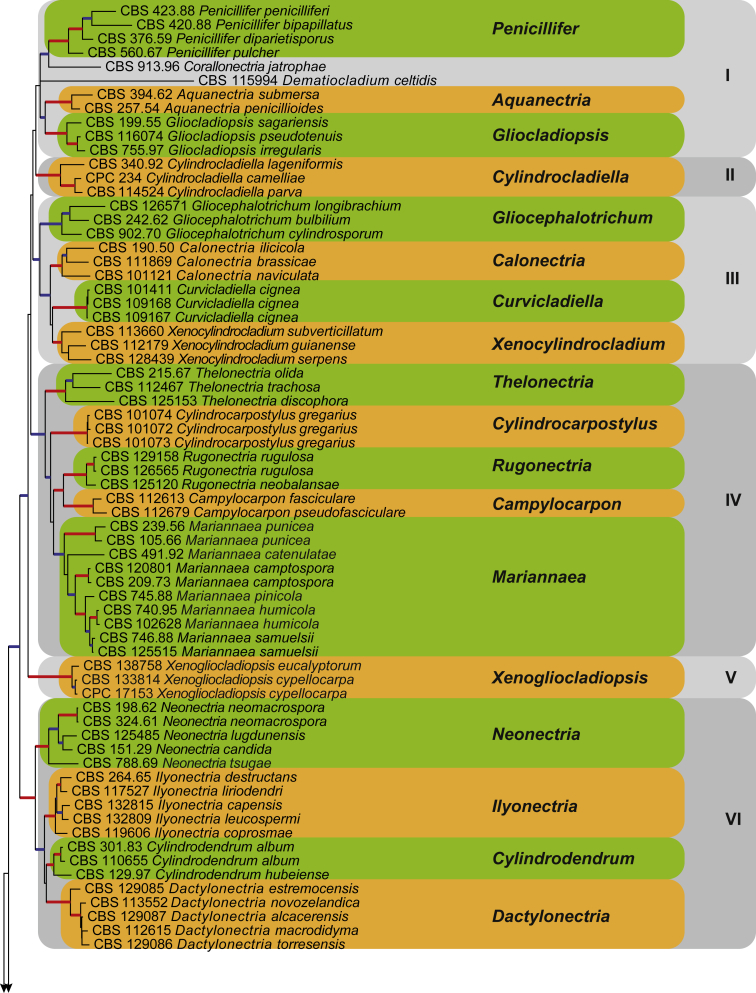

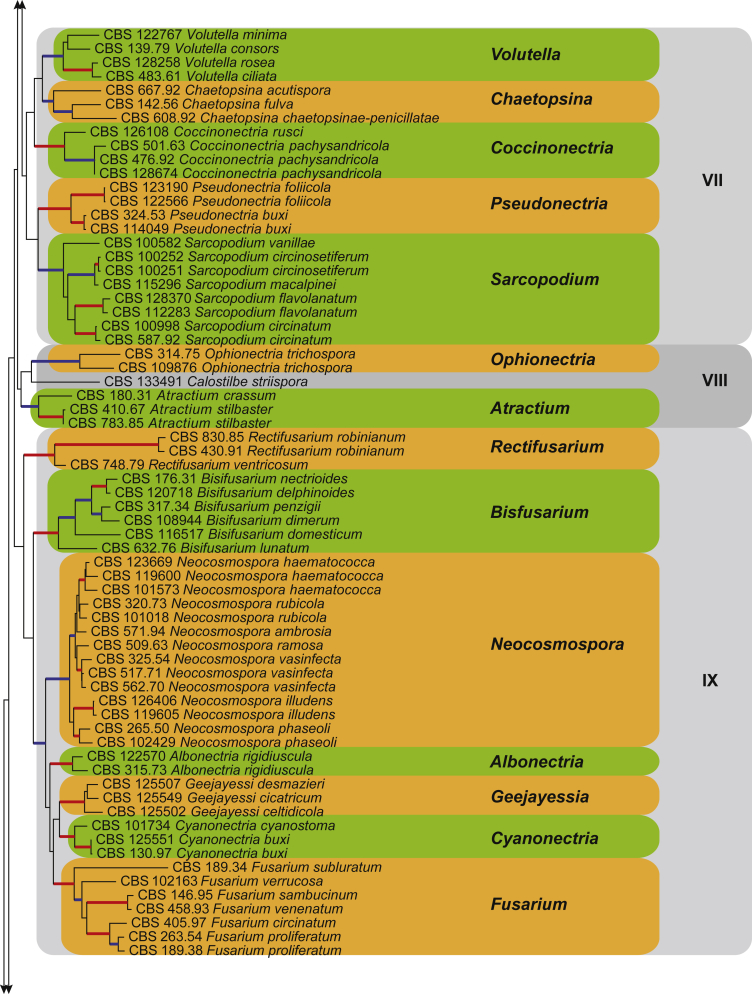

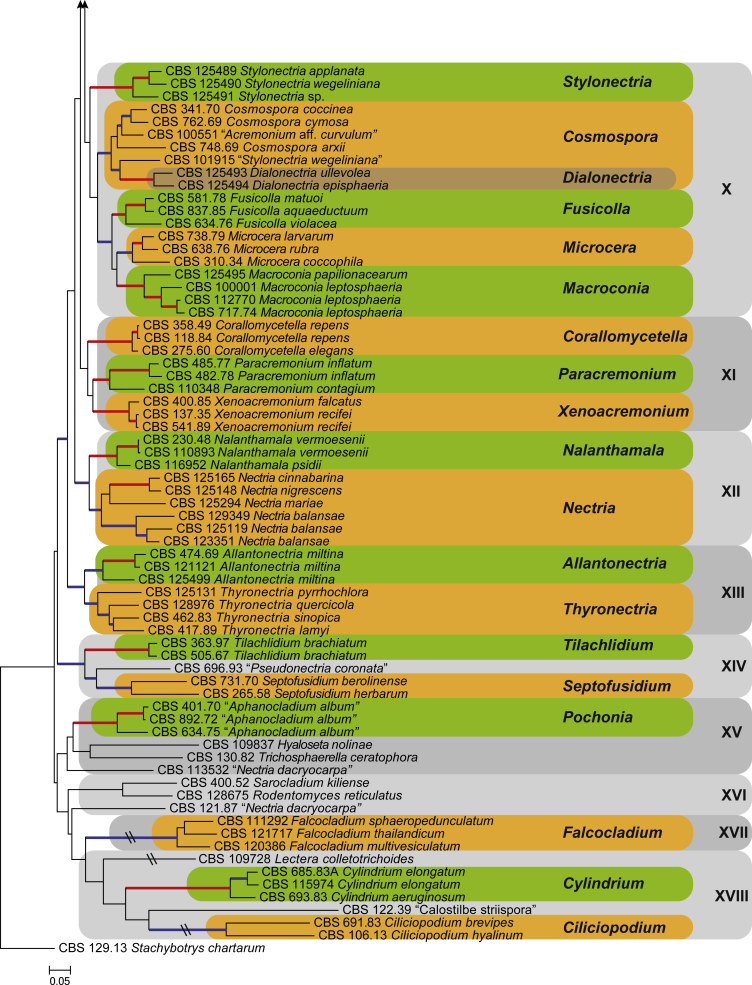

The Bayesian consensus tree confirmed the tree topology obtained from the ML analysis, and therefore only the ML consensus tree with bootstrap support values (BS) and posterior probability values (PP) are indicated for well-supported clades in Fig. 1, Fig. 2. Both Fig. 1, Fig. 2 represent the same underlying phylogenetic analyses, but are two different representations of the obtained phylogenetic tree with Fig. 1 providing a collapsed leaf overview of the genera and families, and Fig. 2 providing details at strain level. In Fig. 1, 44 well-supported clades (BS ≥ 75 %; PP ≥ 0.95) were resolved in the super-clade representing the Nectriaceae. Of these, 33 clades represent established genera with the remaining 11 clades representing possible new genera. Three separate single lineages were also resolved within the Nectriaceae super-clade, representing Corallonectria jatrophae (CBS 913.96), Calostilbe striispora (CBS 133491) and Dematiocladium celtidis (CBS 115994).

Fig. 1.

Maximum Likelihood (ML) consensus tree inferred from the combined 10 genes sequence data set providing a collapsed leaf overview of the genera and families. Thickened branches indicate branches present in both the ML and Bayesian consensus trees. Branches with BS = 100 % and PP = 1.0 are in red. Branches with BS ≥ 75 % and PP ≥ 0.95 are in blue. The tree is rooted to Stachybotrys chartarum (CBS 129.13). The arrow indicates the most basal node representing Nectriaceae.

Fig. 2.

The ML consensus tree inferred from the combined 10 genes sequence data set. Thickened branches indicate branches present in both the ML and Bayesian consensus trees. Branches with BS = 100 % and PP = 1.0 are in red. Branches with BS ≥ 75 % and PP ≥ 0.95 are in blue. The tree is rooted to Stachybotrys chartarum (CBS 129.13). Clade numbers are provided to the right of the tree and these are used for reference in the Treatment of Genera section. Coloured blocks represent the accepted genera.

Several clades, representing genera traditionally classified in the Nectriaceae, resolved in well-supported sister clades (BS ≥ 75 %; PP ≥ 0.95) of the Nectriaceae super-clade. Isolates representing the species in the genera Tilachlidium (CBS 363. 97 & CBS 505. 67) and Septofusidium (CBS 265.58 & CBS 731.70), along with an isolate listed as “Pseudonectria coronata” (CBS 696.93), formed a well-supported clade (BS ≥ 75 %; PP ≥ 0.95) basal to the Nectriaceae super-clade. Representatives of the genera Aphanocladium (CBS 401.70, CBS 634.75 & CBS 892.72; BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0), Ciliciopodium (CBS 106.13 & CBS 691.83; BS ≥ 75 %, PP ≥ 0.95), Cylindrium (CBS 685.83A, CBS 693.83 & CBS 115974; BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0) and Falcocladium (CBS 111292, CBS 121717 & CBS 120386; BS ≥ 75 %, PP ≥ 0.95), each formed separate clades outside the Nectriaceae super-clade.

Treatment of genera (Fig. 2)

Based on phylogenetic inference supported by morphological observations, several novel taxa were identified in this study. Recognised clades, as well as novel families, genera and species are described and discussed below. Only generic circumscriptions are provided for known taxa where the descriptions are available in MycoBank, or in recently published scientific papers.

Clade I

Aquanectria L. Lombard & Crous, gen. nov. MycoBank MB810949.

Etymology: Name refers to the aquatic niche of these fungi.

Ascomata perithecial, superficial, scattered or aggregated in groups, ovate to subglobose, collapsing laterally when old, brown-orange to orange-red, with papillate ostiolar region. Asci cylindrical to clavate, 8-spored. Ascospores ellipsoid to fusiform, hyaline, 1-septate, with a slight constriction at the septum. Conidiophores in aquatic environment erect, solitary, septate, hyaline, branched, with verticillate penicillus with 1–4 phialides. Phialides cylindrical, tip with periclinal thickening, collarette often tubular, not flared. Conidia filiform, curved to slightly sigmoid, aseptate to 1-septate, hyaline, smooth. Chlamydospores formed intercalary, pale to dark brown, containing a large oil guttule, aggregating to form sclerotia (adapted from Ingold 1942 and Ranzoni 1956).

Type species: Aquanectria penicillioides (Ingold) L. Lombard & Crous.

Notes: The aquatic genus Aquanectria is established here to accommodate two fungal species previously treated as members of the genera Flagellospora and Heliscus (Ingold, 1942, Ranzoni, 1956, Hudson, 1961). Recent studies (Baschien et al., 2013, Duarte et al., 2015) showed that species in the aquatic genus Flagellospora belongs to the Helotiales based on the type species, F. curvula. Furthermore, Lombard et al. (2014b) synonymised the genus Heliscus, based on the type species H. lugdunensis, under the genus Neonectria. In this study, CBS 257.54 (= F. penicillioides) clustered with the ex-type strain (CBS 394.62) of Heliscus submersus in a well-supported clade (BS = 100, PP = 1.0) sister to the clade representing the genus Gliocladiopsis. Therefore, new combinations are required to accommodate these fungi in the genus Aquanectria with A. penicillioides as type.

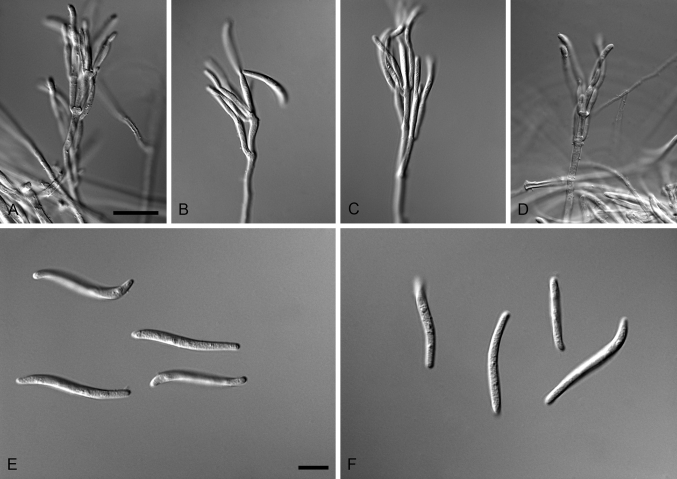

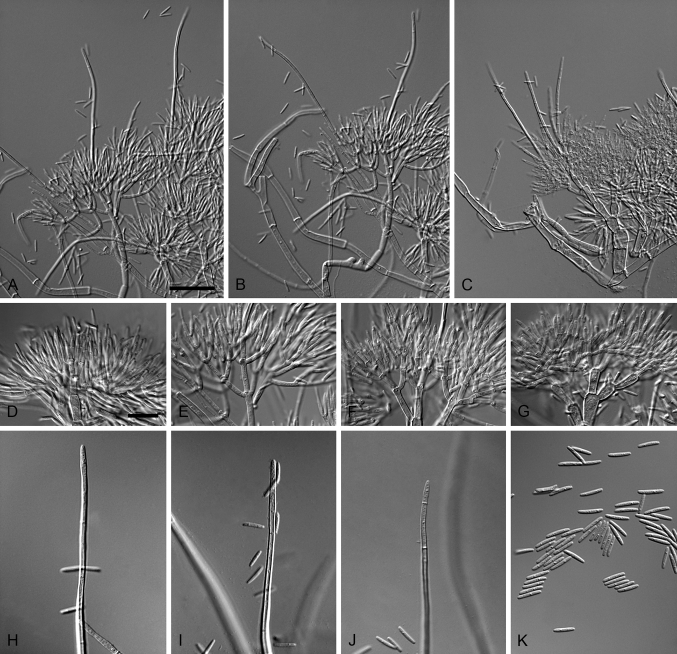

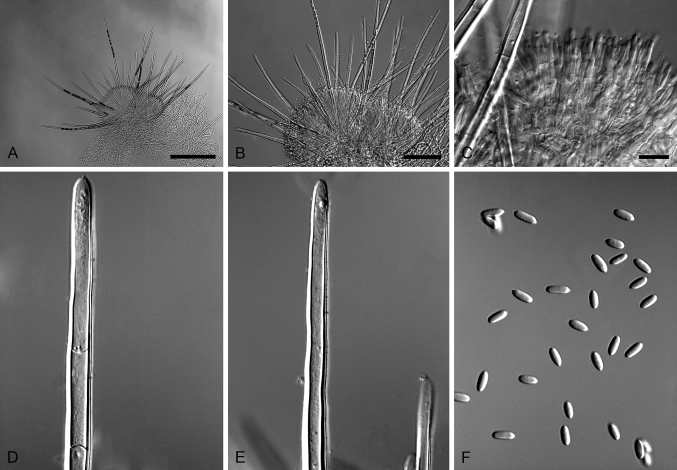

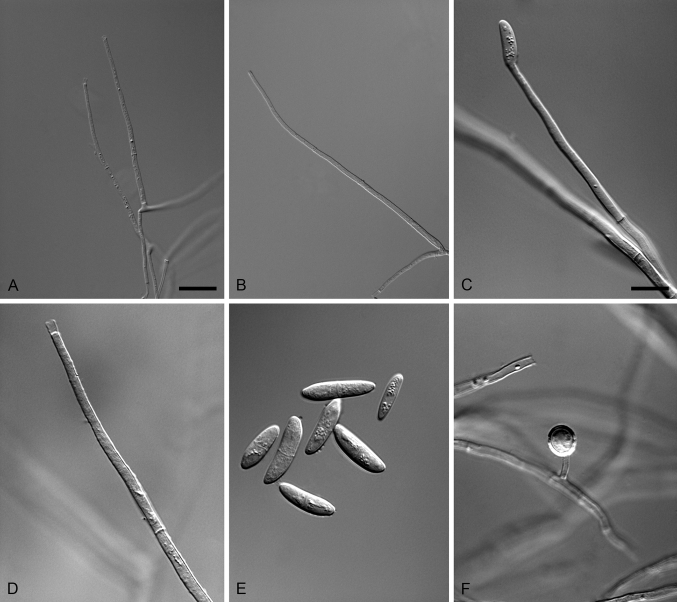

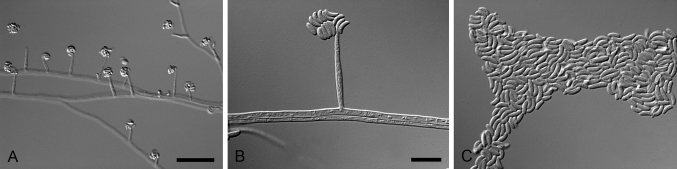

Aquanectria penicillioides (Ingold) L. Lombard & Crous, comb. nov. MycoBank MB810950. Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Aquanectria penicillioides (CBS 257.54). A–D. Conidiophores. E–F. Conidia. Scale bars: A = 20 μm (apply to B–D); E = 10 μm (apply to F).

Basionym: Flagellospora penicillioides Ingold, Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 27: 44. 1942.

= Nectria penicillioides Ranzoni, Amer. J. Bot. 43: 17. 1956.

Material examined: USA, California, Napa County, Green Valley Falls, on decaying leaves of Acer sp. submerged in a stream, Dec. 1954, F.V. Ranzoni, culture CBS 257.54.

Descriptions and illustrations: Ingold, 1942, Ranzoni, 1956.

Aquanectria submersa (H.J. Huds.) L. Lombard & Crous, comb. nov. MycoBank MB810162.

Basionym: Heliscus submersus H.J. Huds., Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 44: 91. 1961.

Material examined: Jamaica, St. Andrew, Hardwar Gap, on decaying leaves submerged in a stream, 1960, H.J. Hudson, (holotype IMI 76792 (not seen), culture ex-type CBS 394.62, sterile).

Description and illustration: Hudson (1961).

Notes: Based on the description provided by Hudson (1961), the fungus formerly known as Heliscus submersus belongs to the genus Aquanectria supported by phylogenetic inference in this study. Hudson (1961) placed this fungus in the aquatic fungal genus Heliscus, as the conidia formed two conical arms at the apex. Other members of the genus Heliscus, however, are known to produce three or more conical arms at the apex (Saccardo, 1880, Ingold, 1942, Webster, 1959). The two conical arms of A. submersa could either represent an atypical character for this species or the initiation of germination tubes at the apex of the conidia. The morphology of A. submersa could not be confirmed, as the ex-type strain could not be induced to sporulate by the addition of sterile water, carnation leaf pieces and/or toothpicks to the culture surface.

Corallonectria C. Herrera & P. Chaverri, Mycosystema 32: 539. 2013. MycoBank MB803108.

Ascomata perithecial, seated on short red stalks, in clusters of two or more, ovoid to obpyriform, not collapsing or collapsing when pinched laterally, orange-red to scarlet, with white to yellow furfuraceous coating below apex, apex acute, smooth, scarlet. Asci clavate, apex simple, 8-spored arranged biseriately. Ascospores smooth, fusiform-ellipsoid, sometimes reniform, 1-septate, often slightly constricted at septum, pale brown when discharged. Synnemata and rhizomorphs formed in culture. Synnemata cylindrical, slender to robust, straight to curved, rarely branching, appearing furfuraceous with loose, white hyphae, with a terminal cupulate capitulum, pale luteous. Rhizomorphs dichotomously branched, immersed in agar. Conidiophores unbranched or once simple monochasial or monoverticillate. Phialides cylindrical and hyaline. Conidial mass forming inside cupulate capitula, flame-shaped, luteous. Conidia fusarium-like, long-fusiform, slightly curved at the apical and basal ends, apical cell acute, basal cell pedicellate, hyaline, 3–4(–5)-septate (adapted from Herrera et al. 2013a).

Type species: Corallonectria jatrophae (A. Møller) C. Herrera & P. Chaverri, Mycosystema 32: 539. 2013. MycoBank MB803109.

≡ Corallomyces jatrophae A. Møller, Bot. Mitt. Trop. 9: 295. 1901, nom. illeg., Art. 53.

≡ Nectria jatrophae (A. Møller) Wollenw., Handb. Pflanzenkrank.: 560. 1931.

≡ Corallomycetella jatrophae (A. Møller) Rossman & Samuels, Stud. Mycol. 42: 114. 1999.

= Nectria madeirensis Henn., Hedwigia 43: 244. 1904.

= Macbridella amazonensis Bat., J.L. Bezerra & C.R. Almeida, Anais XIV Congr. Soc. Bot. Brasil: 118. 1964.

≡ Nectria amazonensis (Bat., J.L. Bezerra & C.R. Almeida) Samuels, Canad. J. Bot. 51: 1278. 1973.

Description and illustrations: Herrera et al. (2013b).

Notes: Corallonectria is a monotypic genus with C. jatrophae as type species. Our phylogeny placed the ex-type isolate (CBS 913.96) of C. jatrophae basal to the clade representing Penicillifer (= Viridispora).

Dematiocladium Allegr. et al., Mycol. Res. 109: 836. 2005. MycoBank MB28939.

Ascomatal state not known. Setae arising from pseudoparenchymatous cells in a basal stroma, adjacent to cells that give rise to conidiophore stipe, extending beyond the conidiophores; setae unbranched, straight to flexuous, brown, verruculose, thick-walled with basal cell initially smooth, becoming brown with age, tapering from a base which is either rounded and well-defined, or cylindrical and continuous with the cells in the pseudoparenchymatous stroma, to an acutely or subobtusely rounded apex, which is pale brown, thin-walled towards the apex; apical cell sometimes becoming fertile with age, forming an apical penicillate conidiophore. Conidiophores consist of a stipe, a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and rarely, an extension of the stipe, signifying continued growth and eventual branching of stipe and secondary penicillate conidiophores. Stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, brown at the base, arising from tightly arranged pale to medium brown pseudoparenchymous cells in a basal stroma, frequently terminating in a swollen, globose apical cell, giving rise to 1–6 primary branches. Conidiogenous apparatus branched (–4), hyaline, smooth, with terminal branches producing 1–6 phialides. Phialides elongate doliiform to reniform or subcylindrical, straight to slightly curved, aseptate; apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Conidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, hyaline, 1(–2)-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel clusters by colourless slime. Chlamydospores globose, thick-walled, brown, in intercalary chains (adapted from Crous et al. 2005).

Type species: Dematiocladium celtidis Allegr. et al., Mycol. Res. 109: 836. 2005. MycoBank MB344508.

Description and illustrations: Crous et al. (2005).

Notes: Dematiocladium celtidis (ex-type CBS 115994) formed a single lineage basal to the clade representing the genus Penicillifer and the single lineage representing Corallonectria jatrophae. Recently, Crous et al. (2014) introduced a second species in this genus, D. celtidicola from China, which was not available for this study at the time.

Gliocladiopsis S.B. Saksena, Mycologia 46: 662. 1954. MycoBank MB8341.

= Glionectria Crous & C. L. Schoch, Stud. Mycol. 45: 58. 2000.

Ascomata perithecial, superficial, densely gregarious, seated on a thin basal stroma, obovoid to broadly obpyriform, collapsing laterally when drying, warted, red-brown with a dark red stromatic base, changing to dark red in KOH. Asci unitunicate, 8-spored, cylindrical, sessile, with a flattened apex, and a refractive apical apparatus. Ascospores uniseriate, overlapping, hyaline, ellipsoidal, smooth, medianly 1-septate. Conidiomata sporodochial, consisting of numerous aggregated penicillate conidiophores, or reduced to separate penicillate or subverticillate conidiophores. Conidiophores monomorphic, penicillate, consisting of a stipe and a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, rarely dimorphic, penicillate and subverticillate. Stipe septate, hyaline, smooth. Conidiogenous apparatus with several series of aseptate or 1-septate branches, each terminal branch producing 2–6(–7) phialides. Phialides doliiform to cymbiform to cylindrical, hyaline, aseptate, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Conidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight to curved, (0–)1-septate, lacking visible abscission scars, but frequently with a flattened base, held in fascicles by colourless slime (adapted from Saksena 1954 and Lombard & Crous 2012).

Type species: Gliocladiopsis sagariensis S.B. Saksena, Mycologia 46: 663. 1954. MycoBank MB297822.

Descriptions and illustrations: Saksena, 1954, Crous, 2002, Lombard and Crous, 2012.

Notes: Representative strains of the genus Gliocladiopsis formed a monophyletic clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0) sister to the clade representing the aquatic genus Aquanectria. Interestingly, these two genera clustered together in a larger clade (BS ≥ 75 %, PP ≥ 0.95), even though they do not share the same ecological niche. Gliocladiopsis species are characteristically soil-borne (Lombard & Crous 2012). The genera do, however, share similar conidiophore morphology.

Penicillifer Emden, Acta Bot. Neerl. 17: 54. 1968. MycoBank MB9256.

= Viridispora Samuels & Rossman, Stud. Mycol. 42: 166. 1999.

Ascomata non-stromatic, superficial, solitary, globose to pyriform, red, orange-brown, tan, or brown, not reacting or changing to red in KOH, coarsely warted or glabrous. Asci clavate, apex simple. Ascospores green, 1-septate and smooth. Conidiophores erect, solitary, septate, hyaline, unbranched and monophialidic, or with a biverticillate penicillus. Phialides cylindrical, tip with periclinal thickening, collarette often tubular, not flared. Conidia cylindrical to slightly naviculate, 1-septate, hyaline, smooth, with blunt papilla at one or both ends (adapted from Samuels 1989 and Rossman et al. 1999).

Type species: Penicillifer pulcher Emden, Acta Bot. Neerl. 17: 54. 1968. MycoBank MB335703.

Descriptions and illustrations: Samuels, 1989, Polishook et al., 1991, Rossman et al., 1999.

Notes: The sexual genus Viridispora was established by Rossman et al. (1999) to accommodate species in the genera Nectria (Samuels, 1989, Watanabe, 1990) and Neocosmospora (Polishook et al. 1991) that had Penicillifer asexual morphs. Penicillifer was introduced by Emden (1968), typified by P. pulcher, for a fungus isolated from soil in the Netherlands. At present, the genus Viridispora accommodates four species, V. alata (= P. bipapillatus), V. diparietispora (= P. furcatus), V. fragariae (= P. fragariae) and V. penicilliferi (= P. macrosporus), each with its own Penicillifer asexual morphs (Samuels, 1989, Watanabe, 1990, Polishook et al., 1991, Rossman et al., 1999). So far, only P. japonicus (Matsushima 1985) has no associated sexual morph. Because the generic name Penicillifer (1968) is older than Viridispora (1999) for this monophyletic group of fungi (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0), we propose that the sexual morph, Viridispora, be suppressed in favour of the asexual morph, Penicillifer. A new combination is, however, required for P. furcatus, as the epithet Pseudonectria diparietispora (1957) pre-dates that of Penicillifer furcatus (1991) and is provided below.

Penicillifer diparietisporus (J.H. Miller, Giddens & A.A. Foster) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous, comb. nov. MycoBank MB810951.

Basionym: Pseudonectria diparietispora J.H. Miller, Giddens & A.A. Foster, Mycologia 49: 793. 1957 (1958, as ‘diparietospora’).

≡ Neocosmospora diparietispora (J.H. Miller, Giddens & A.A. Foster) Rossman, Samuels & Lowen, Mycologia 85: 699. 1993.

≡ Viridispora diparietispora (J.H. Miller, Giddens & A.A. Foster) Samuels & Rossman, Stud. Mycol. 42: 167. 1999.

= Neocosmospora arxii Udagawa, Horie & P. Cannon, Sydowia 41: 353. 1989.

= Neocosmospora endophytica Polishook, Bills & Rossman, Mycologia 83: 798. 1991.

= Penicillifer furcatus Polishook, Bills & Rossman, Mycologia 83: 798. 1991.

Clade II

Cylindrocladiella Boesew., Canad. J. Bot. 60: 2289. 1982. MycoBank MB7869.

= Nectricladiella Crous & C. L. Schoch, Stud. Mycol. 45: 54. 2000.

Ascomata perithecial, superficial, solitary, basal stroma absent, globose to obpyriform, collapsing laterally when dry, smooth, with several minute, brown setae arising from the perithecial wall surface, red, changing colour in KOH, ostiole consisting of clavate cells, lined with inconspicuous periphyses. Asci unitunicate, 8-spored, cylindrical, sessile, thin-walled, with a flattened apex, and a refractive apical apparatus. Ascospores uniseriate, overlapping, hyaline, ellipsoid to fusoid with obtuse ends, smooth, 1-septate. Conidiophores monomorphic, penicillate, or dimorphic (penicillate and subverticillate), mononematous, hyaline. Penicillate conidiophores consist of a stipe, a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, a stipe extension, and a terminal vesicle. Subverticillate conidiophores consist of a stipe, and one or two series of phialides. Stipe septate, hyaline, smooth. Stipe extensions aseptate, straight, thick-walled, with one basal septum, terminating in a thin-walled vesicle of characteristic shape. Conidiogenous apparatus with primary branches aseptate to 1-septate, secondary branches aseptate, terminating in 2–4 phialides. Phialides cylindrical, straight or doliiform to reniform to cymbiform, hyaline, aseptate, apex with minute periclinal thickening and collarette. Conidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (0–)1(–3)-septate, frequently slightly flattened at the base, held in asymmetrical clusters by colourless slime. Chlamydospores brown, thick-walled, more frequently arranged in chains than clusters (adapted from Boesewinkel 1982 and Lombard et al. 2012).

Type species: Cylindrocladiella parva (P.J. Anderson) Boesew., Canad. J. Bot. 60: 2289. 1982.

≡ Cylindrocladium parvum P.J. Anderson, Mass. Agric. Exp. Sta. Bull. 183: 37. 1919.

Descriptions and illustrations: Boesewinkel, 1982, Lombard et al., 2012.

Note: Representatives strains of the genus Cylindrocladiella formed a monophyletic clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0), sister to the members of Clade I.

Clade III

Calonectria De Not., Comment. Soc. Crittog. Ital. 2: 477. 1867. MycoBank MB746.

= Cylindrocladium Morgan, Bot. Gaz. 17: 191. 1892.

= Candelospora Rea & Hawley, Proc. Roy. Irish Acad., B. 13: 11. 1912.

Ascomata perithecial, solitary or in groups, globose to subglobose to ovoid, yellow to orange to red or red-brown to brown, turning darker red to red-brown in KOH, rough-walled; perithecial apex consisting of flattened, thick-walled hyphal elements with rounded tips forming a palisade, discontinuous with warty wall, gradually becoming thinner towards the ostiolar canal, and merging with outer periphyses; perithecial base consisting of dark brown-red, angular cells, merging with a erumpent stroma, cells of the outer wall layer continuing into the pseudoparenchymatous cells of the erumpent stroma. Asci 8-spored, clavate, tapering to a long thin stalk. Ascospores aggregated in the upper third of the ascus, hyaline, smooth, fusoid with rounded ends, straight to sinuous, unconstricted, or constricted at the septa. Megaconidiophores if present, borne on the agar surface or immersed in the agar; stipe extensions mostly absent; conidiophores unbranched, terminating in 1–3 phialides, or sometimes with a single subterminal phialide; phialides straight to curved, cylindrical, seemingly producing a single conidium; periclinal thickening and an inconspicuous, divergent collarette rarely visible. Megaconidia hyaline, smooth, frequently remaining attached to the phialide, multi-septate, widest in the middle, bent or curved, with a truncated base and rounded apical cell. Macroconidiophores consist of a stipe, a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, a stipe extension, and a terminal vesicle; stipe septate, hyaline or slightly pigmented at the base, smooth or finely verruculose; stipe extensions septate, straight to flexuous, mostly thin-walled, terminating in a thin-walled vesicle of characteristic shape. Conidiogenous apparatus with 0–1-septate primary branches; up to eight additional branches, mostly aseptate, each terminal branch producing 1–6 phialides; phialides cylindrical to allantoid, straight to curved, or doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous divergent collarette. Macroconidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight or curved, widest at the base, middle, or first basal septum, 1- to multi-septate, lacking visible abscission scars, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Microconidiophores consist of a stipe and a penicillate or subverticillate arrangement of fertile branches. Primary branches 0–1-septate, subcylindrical; secondary branches 0–1-septate, terminating in 1–4 phialides; phialides cylindrical, straight to slightly curved, apex with minute periclinal thickening and marginal frill. Microconidia cylindrical, straight to curved, rounded at apex, flattened at base, 1(–3)-septate, held in asymmetrical clusters by colourless slime (adapted from Crous 2002).

Type species: Calonectria pyrochroa (Desm.) Sacc., Michelia 1: 308. 1878.

≡ Nectria pyrochroa Desm., Bull. Soc. Bot. France 4: 998. 1857.

= Calonectria daldiniana De Not., Comment. Soc. Crittog. Ital. 2: 477. 1867.

= Ophionectria puiggarii Speg., Bol. Acad. Nac. Ci. 11: 532. 1889.

= Nectria abnormis Henn., Hedwigia 36: 219. 1897.

= Cylindrocladium ilicicola (Hawley) Boedijn & Reitsma, Reinwardtia 1: 57. 1950.

≡ Candelospora ilicicola Hawley, Proc. Roy. Irish Acad., B. 31: 11. 1912.

Descriptions and illustrations: Rossman et al., 1999, Crous, 2002, Lombard et al., 2010b.

Notes: Representative strains of the genus Calonectria formed a monophyletic clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0) closely related to the clades representing Curvicladiella and Xenocylindrocladium, respectively. Based on the ICN for algae, fungi and plants, new combinations are required for C. morganii and C. scoparia as there are older epithets available for both species.

Calonectria candelabra (Viégas) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous, comb. nov. MycoBank MB810952.

Basionym: Cylindrocladium candelabrum Viégas, Bragantia 6: 370. 1946.

= Calonectria scoparia Ribeiro & Matsuoka, In: Ribeiro, M.Sc. Thesis, Heterotalismo em C. scoparium Morgan: 28. 1978 (nom. inval., Art. 29).

≡ Calonectria scoparia Peerally, Mycotaxon 40: 341. 1991.

Calonectria cylindrospora (Ellis & Everh.) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous, comb. nov. MycoBank MB810953.

Basionym: Diplocladium cylindrosporum Ellis & Everh., Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 27: 58. 1900.

= Cylindrocladium scoparium Morgan, Bot. Gaz. 17: 191. 1892.

= Cylindrocladium pithecolobii Petch, Ann. Roy. Bot. Gard. (Peradeniya) 6: 244. 1917.

= Cylindrocladium ellipticum Alfieri, C.P. Seym. & Sobers, Phytopathology 60: 1213. 1970.

= Calonectria morganii Crous, Alfenas & M.J. Wingf. Mycol. Res. 97: 706. 1993.

Curvicladiella Decock & Crous, Stud. Mycol. 55: 225. 2006. MycoBank MB500866.

Ascomatal state unknown. Conidiomata sporodochial or synnematal, consisting of numerous penicillate conidiophores arising from a stroma of brown, thick-walled chlamydospores. Conidiophores consist of a thick-walled, smooth to finely verruculose, septate, pale brown to brown basal stipe, a conidiogenous apparatus and several sterile stipe extensions that have 1(–2) apical and one basal septum; stipe extensions avesiculate; apical cell thick-walled, verruculose, pale brown, prominently curved, tapering towards a bluntly rounded acute apex. Conidiogenous apparatus with several hyaline, smooth, subcylindrical, straight to slightly curved conidiophore branches; phialides hyaline, smooth, doliiform to reniform or subcylindrical, apex with minute periclinal thickening, and inconspicuous, flared collarette. Conidia cylindrical, septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in heads of colourless slime. Chlamydospores arranged intercalarily, often aggregating to form microsclerotia (adapted from Decock & Crous 1998 and Crous et al. 2006).

Type species: Curvicladiella cignea Decock & Crous, Stud. Mycol. 55: 225. 2006.

Descriptions and illustrations: Decock and Crous, 1998, Crous et al., 2006

Note: The monotypic genus Curvicladiella formed a well-supported clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0) closely related to the genera Calonectria and Xenocylindrocladium.

Gliocephalotrichum J.J. Ellis & Hesselt., Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 89: 21. 1962. MycoBank MB8340.

Ascomata perithecial, superficial, globose to subglobose, scarlet, turning purple in KOH, with a white to pale luteous amorphous coating and hyphal stromatic base. Asci unitunicate, narrowly clavate, 8-spored, with flattened apex and a minute refractive ring. Ascospores hyaline, ellipsoidal, smooth, aseptate. Conidiophores consisting of a septate, hyaline, pale luteous to pale brown stipe and a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches subtended by septate stipe extensions. Stipe extensions hyaline, septate, terminating in narrowly to broadly clavate vesicles. Conidiogenous apparatus with a series of aseptate, hyaline to pale brown branches, each terminating in 2–8 phialides. Phialides clavate to cylindrical, hyaline, aseptate, constricted at the apex, with minute periclinal thickening. Conidia cylindrical to ellipsoidal, straight to slightly curved, aseptate, accumulating in a white to luteous mucoid mass above the phialides (adapted from Rossman et al. 1993 and Lombard et al. 2014a).

Type species: Gliocephalotrichum bulbilium J.J. Ellis & Hesselt., Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 89: 21. 1962.

Descriptions and illustrations: Rossman et al., 1993, Lombard et al., 2014a.

Notes: Species of Gliocephalotrichum are soil-borne fungi generally associated with post-harvest fruit spoilage of several important tropical fruit crops (Lombard et al. 2014a). Representatives of Gliocephalotrichum clustered in a monophyletic clade (BS ≥ 75 %, PP ≥ 0.95), basal to the clades representing Calonectria, Curvicladiella and Xenocylindrocladium.

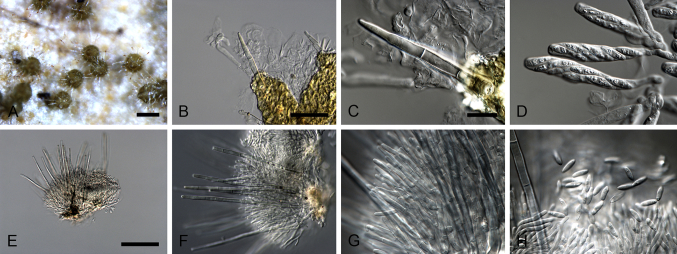

Xenocylindrocladium Decock et al., Mycol. Res. 101: 788. 1997. MycoBank MB27788. Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Xenocylindrocladium serpens (ex-type CBS 128439). A–C. Conidiophores. D–G. Conidiogenous apparatus with doliiform to reniform phialides. H–I. Avesiculate stipe extensions. J. Conidia. K. Chlamydospores. Scale bars: A = 50 μm (apply to B–C); D = 10 μm (apply to E–G); H = 10 μm (apply to I–K).

= Xenocalonectria Crous & C.L. Schoch, Stud. Mycol. 45: 50. 2000.

Ascomata perithecial, superficial, solitary or aggregated, globose to subglobose, warted, yellow to red and with a dark red stromatic base; ostiolar periphyses hyaline, tubular with rounded ends. Asci unitunicate, 8-spored, cylindrical, with long basal stalks, a flattened apex, and a refractive apical apparatus. Ascospores aggregate in the upper third of the ascus, hyaline, broadly to narrowly ellipsoidal, smooth, medianly 1-septate. Conidiophores consisting of a stipe, a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and an avesiculate stipe extension. Stipe septate, hyaline, smooth; stipe extensions septate, straight to flexuous or sinuous. Conidiogenous apparatus with aseptate or 1-septate primary branches; aseptate secondary, tertiary and quaternary branches, each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Conidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight or curved, septate, lacking visible abscission scars, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by slime (adapted from Decock et al. 1997).

Type species: Xenocylindrocladium serpens Decock et al., Mycol. Res. 101: 788. 1997.

Notes: The genus Xenocylindrocladium includes three species described from the tropics, isolated from plant debris (Decock et al., 1997, Crous et al., 2001). At the same time, Decock et al. (1997) introduced the sexual morph of X. serpens as Nectria serpens, which was later transferred to the genus Xenocalonectria by Schoch et al. (2000). Given the name changes required if the genus name Xenocalonectria was used, we propose that the generic name Xenocalonectria be suppressed in favour of Xenocylindrocladium, which also has priority by date and therefore no new combinations are required. Representatives of the genus Xenocylindrocladium formed a monophyletic clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0), closely related to the genera Curvicladiella and Calonectria.

Clade IV

Campylocarpon Halleen et al., Stud. Mycol. 50: 448. 2004. MycoBank MB28858.

Ascomatal state unknown. Asexual state cylindrocarpon-like. Conidiophores arise laterally from single or fasciculate aerial hyphae, carried singularly or aggregated, consisting of a stipe bearing several phialides or a penicillus of irregular branches with terminal branches bearing one or several phialides. Phialides cylindrical or narrowly flask-shaped. Macroconidia cylindrical, typically curved, (1–)3–4(–5)-septate, with minute tapering, obtuse ends, sometimes somewhat more strongly tapering at the base; base with or without an obscure hilum. Microconidia and chlamydospores not observed (adapted from Halleen et al. 2004).

Type species: Campylocarpon fasciculare Schroers et al., Stud. Mycol. 50: 448. 2004.

Description and illustrations: Halleen et al. (2004).

Notes: The monophyletic clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0) representing the asexual genus Campylocarpon is closely related but separate from the clade representing the genus Rugonectria. Both these genera share several morphological characters, such as having cylindrocarpon-like asexual states. Neither is known to produce chlamydospores in culture.

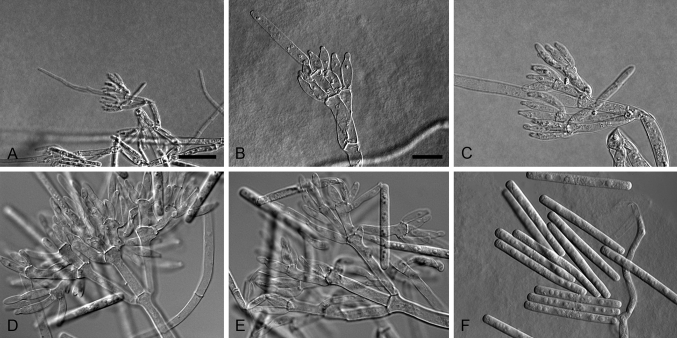

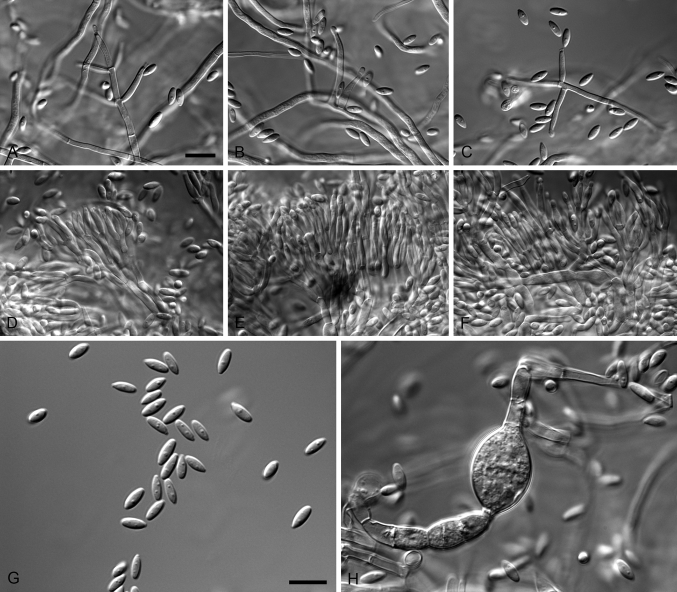

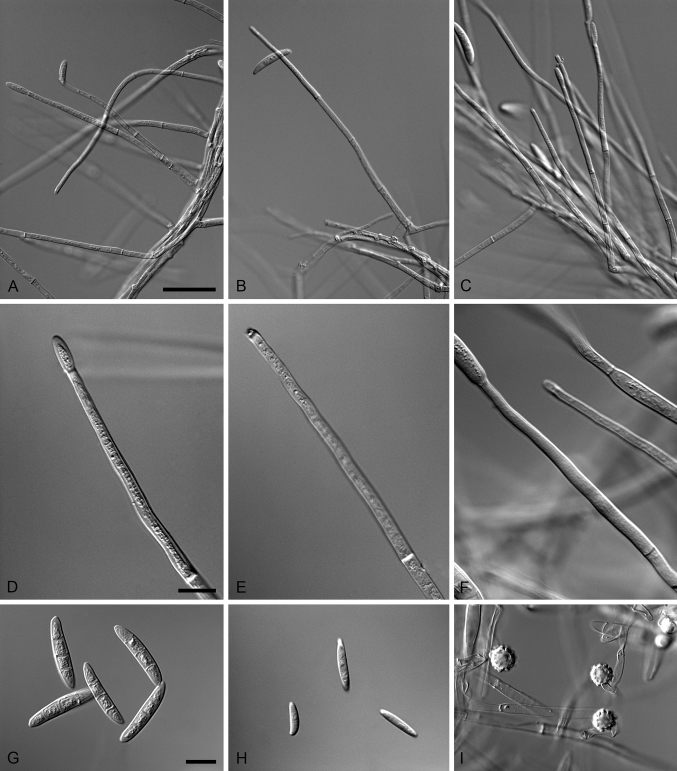

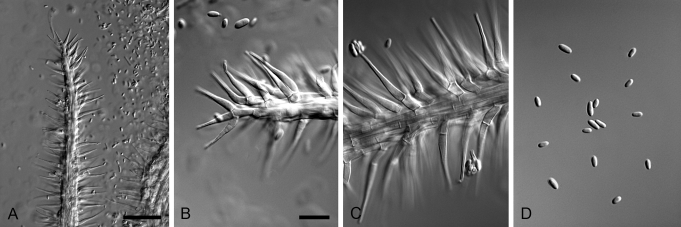

Cylindrocarpostylus R. Kirschner & Oberw., Mycol. Res. 103: 1155. 1999. MycoBank MB28330. Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Cylindrocarpostylus gregarius (ex-type CBS 101072). A–C. Conidiophores. D–E. Conidiogenous apparatus with cylindrical to allantoid phialides. F. Conidia. Scale bars: A = 50 μm; B = 10 μm (apply to C–F).

Ascomatal state unknown. Conidiophores arise from hyphae, consisting of a stipe and penicillate arrangement of fertile branches. Stipe septate, smooth, becoming verruculose with age, initially hyaline, turning yellow to brown. Conidiogenous apparatus with aseptate primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary branches, each terminal branch producing 2–4 phialides; phialides cylindrical to allantoid, hyaline, aseptate, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Conidia hyaline, smooth, cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight or slightly curved, 0–3-septate, lacking visible abscission scars (adapted from Kirschner & Oberwinkler 1999).

Type species: Cylindrocarpostylus gregarius (Bres.) R. Kirschner & Oberw., Mycol. Res. 103: 1155. 1999.

≡ Diplocladium gregarium Bres., Ann. Mycol. 1: 127. 1903.

≡ Cylindrocladium gregarium (Bres.) de Hoog, Persoonia 10: 75. 1978.

Description and illustrations: Kirschner & Oberwinkler (1999).

Note: Representatives of the monotypic genus Cylindrocarpostylus formed a monophyletic clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0), separate from all other members of Clade IV.

Mariannaea G. Arnaud ex Samson, Stud. Mycol. 6: 74. 1974. MycoBank MB8846.

Ascomata perithecial with inconspicuous or absent stroma, solitary, globose with a flat apex, not collapsing or collapsing laterally by pinching when dry, pale yellow, orange or brown, not reacting in KOH. Perithecial wall smooth or finely roughened. Asci cylindrical to narrowly clavate, sometimes with an inconspicuous apical ring, 8-spored. Ascospores 1-septate, hyaline, smooth to spinulose. Conidiophores verticillate to penicillate, hyaline, with phialides arising directly from the stipe or forming whorls of metulae on lower parts of the stipe. Stipe hyaline, becoming yellow-brown at the base. Phialides monophialidic, flask-shaped, hyaline, usually with obvious periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarettes. Conidia aseptate, hyaline, in chains that collapse to form slimy heads. Chlamydospores globose to ellipsoidal, hyaline, formed in intercalary chains (adapted from Samson 1974).

Type species: Mariannaea elegans (Corda) Samson, Stud. Mycol. 6: 75. 1974.

≡ Penicillium elegans Corda, Icones Fung. 2: 17. 1838.

≡ Hormodendron elegans (Corda) Bonorden, Handb. Allg. Mykol.: 76. 1851.

≡ Spicaria elegans (Corda) Harz., Bull. Soc. Imp/Nat. Moscou 44: 238. 1871.

≡ Paecilomyces elegans (Corda) Mason & Hughes apud Hughes, Mycol. Pap. 45: 27. 1951.

Descriptions and illustration: Samson, 1974, Gräfenhan et al., 2011.

Note: Unfortunately no culture or sequences of M. elegans were available to be included in this phylogenetic study.

Mariannaea catenulatae (Samuels) L. Lombard & Crous, comb. nov. MycoBank MB810163.

Basionym: Chaetopsina catenulata Samuels, Mycotaxon 22: 28. 1985.

≡ Nectria chaetopsinae-catenulatae Samuels, Mycotaxon 22: 28. 1985.

≡ Cosmospora chaetopsinae-catenulatae (Samuels) Rossman & Samuels, Stud. Mycol. 42: 119. 1999.

≡ Chaetopsinectria chaetopsinae-catenulatae (Samuels) J. Luo & W.Y. Zhuang, Mycologia 102: 979. 2010.

Description and illustration: Samuels (1985).

Notes: Based on phylogenetic inference in this study, the ex-type culture CBS 491.92, previously known as Chaetopsinectria chaetopsinae-catenulatae (Samuels, 1985, Luo and Zhuang, 2010), clustered in the monophyletic clade (BS ≥ 75 %, PP ≥ 0.95) representing the genus Mariannaea. Therefore, a new combination is provided in the genus Mariannaea. This is the first study to include this ex-type strain in a molecular phylogeny.

Mariannaea pinicola L. Lombard & Crous, nom. nov. MycoBank MB810164.

≡ Nectria mariannaea Samuels & Seifert, Mycotaxon 110: 101. 2009.

≡ Nectria mariannaea Samuels & Seifert, Sydowia 43: 257. 1991. (nom. Inval., Art 23.4).

Etymology: Name derived from the plant host Pinus sp., from which it was collected.

Descriptions and illustrations: Samuels & Seifert (1991).

Notes: Gräfenhan et al. (2011) refrained from transferring Nectria mariannaea to the genus Mariannaea based on insufficient taxonomic information available at that time. As the use of the same epithet would create a tautonym (Art. 23.4), we choose to provide this species with a new epithet.

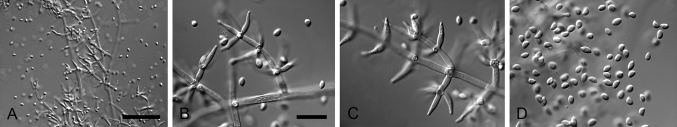

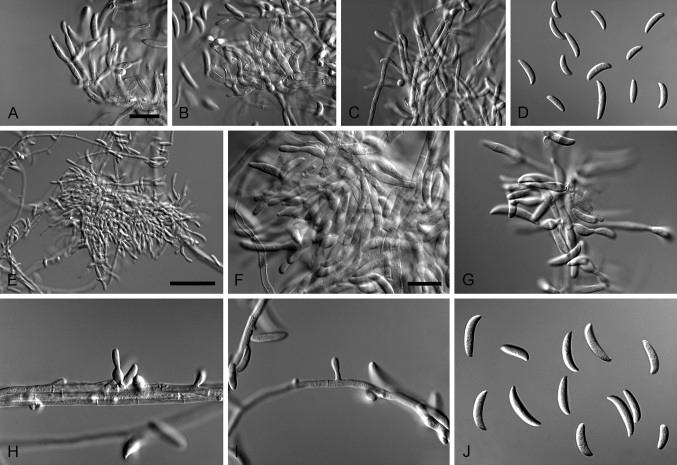

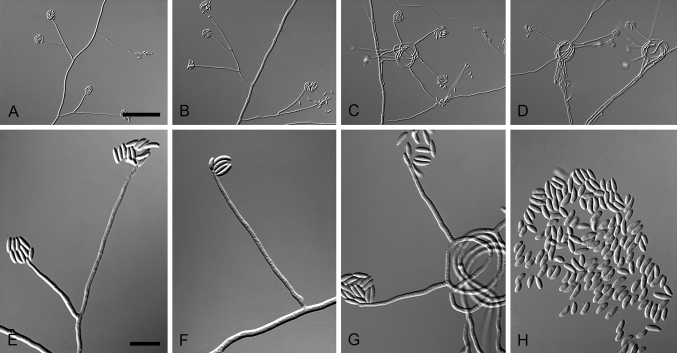

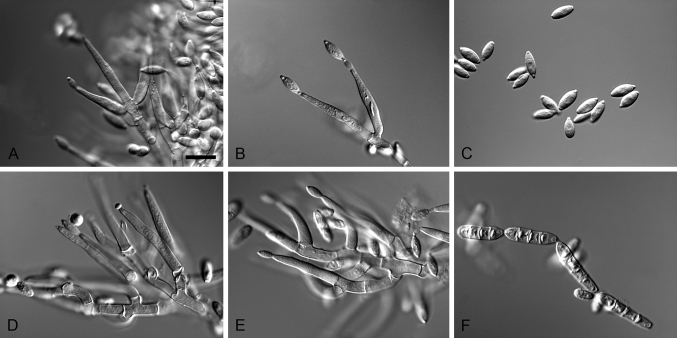

Mariannaea humicola L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB810165. Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Mariannaea humicola (ex-type CBS 740.95). A–C. Conidiophores with verticillate phialides. D. Conidia. Scale bars: A = 50 μm; B = 10 μm (apply to C–D).

Etymology: Name refers to the soil substrate from which this fungus was isolated.

Ascomatal state not observed. Conidiophores arising from the agar surface from aerial hyphae or fascicles, mostly 80–100 μm long, axis 3–7 μm wide, branching verticillately at 2–3 levels, with a terminal whorl of 1–5 phialides, and 1–2 lower nodes of 1–3 phialides, rarely with single phialides. Phialides subulate, sometimes with base slightly swollen, 10–20 μm, 2–4 μm at the broadest part, with periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Conidia fusiform to ellipsoidal to obovoid, hyaline, smooth, (3–)4–6 × 2–3 μm (av. 5 × 3 μm), with a distinct hilum at both or at one end. Chlamydospores not seen.

Culture characteristics: Colonies slow growing on MEA, 45–50 mm diam in 14 d at 24 °C. Surface dirty white in the centre becoming tan to sienna towards the margins with dirty white, irregularly distributed tuffs of fascicles; aerial mycelium abundant. Reverse chestnut becoming umber at the margins.

Materials examined: Brazil, Sao Paulo, from rhizosphere soil under Araucaria angustifolia, Apr. 1995, S. Baldini (holotype CBS H-21953, culture ex-type CBS 740.95 = CCT 4534). Spain, Canary Islands, La Gomera, on decaying wood of unknown tree, Oct. 1999, R.F. Castañeda, culture CBS 102628 = INIFAT C99/130-2.

Notes: Mariannaea humicola is introduced here for two isolates (CBS 740.95 & CBS 102628), which were listed as “Nectria mariannaea” (= M. pinicola) in the CBS collection. Both isolates clustered together in a clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0) separate from the ex-type culture (CBS 754.88) of M. pinicola. The conidia of M. humicola [(3–)4–6 × 2–3 μm (av. 5 × 3 μm)] are smaller than those of M. pinicola [5–9(–17) × (2–)2.5–4.5 μm; Samuels & Seifert 1991] and no chlamydospores were observed for M. humicola, which are readily formed by M. pinicola (Samuels & Seifert 1991).

Rugonectria P. Chaverri & Samuels, Stud. Mycol. 68: 73. 2011. MycoBank MB518563.

Ascomata perithecial, formed on or partially immersed within a stroma, globose to subglobose, warted, orange to red, turning dark red in KOH. Asci cylindrical to clavate, 8-spored. Ascospores 1-septate, ellipsoidal to oblong, hyaline or sometimes yellow. Asexual state cylindrocarpon-like. Microconidiophores monophialidic or sparsely branched, terminating in cylindrical phialides. Microconidia 0–1-septate, ovoid to cylindrical, with rounded ends, hyaline, lacking a prominent basal hilum. Macroconidiophores irregularly branched or in fascicles, terminating in cylindrical phialides. Macroconidia (3–)5–7(–9)-septate, fusiform, curved, tapering towards the ends with an inconspicuous basal hilum. Chlamydospores absent (adapted from Chaverri et al. 2011).

Type species: Rugonectria rugulosa (Pat. & Gaillard) Samuels et al., Stud. Mycol. 68: 73. 2011.

≡ Nectria rugulosa Pat. & Gaillard, Bull. Soc. Mycol. France 4: 115. 1888.

≡ Neonectria rugulosa (Pat. & Gaillard) Mantiri & Samuels, Canad. J. Bot. 79: 339. 2001.

= Cylindrocarpon rugulosum Brayford & Samuels, Sydowia 46: 146. 1994.

Description and illustration: Chaverri et al. (2011).

Note: Representatives of the genus Rugonectria formed a monophyletic clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0), closely related but separate from the clade representing Campylocarpon.

Thelonectria P. Chaverri & C. Salgado, Stud. Mycol. 68: 76. 2011. MycoBank MB518567.

Ascomata perithecial formed superficial or seated on an immersed inconspicuous stroma, globose, subglobose, or pyriform to elongated, smooth or warted, with a prominently darkened papilla or darkly pigmented apex. Asci cylindrical and 8-spored. Ascospores 1-septate, hyaline, ellipsoidal to oblong, becoming pigmented with age. Asexual morph cylindrocarpon-like; microconidiophores and microconidia rare. Macroconidiophores irregularly branched or in fascicules, terminating in cylindrical phialides; macroconidia (3–)5–7(–9)-septate, curved, often broadest at upper third, with rounded apical cell and flattened or rounded basal cells with inconspicuous hilum. Chlamydospores rare, abundant in one species (adapted from Chaverri et al. 2011).

Type species: Thelonectria discophora (Mont.) P. Chaverri & C. Salgado, Stud. Mycol. 68: 76. 2011.

≡ Sphaeria discophora Mont., Ann. Sci. Nat., Bot. II 3: 353. 1835.

≡ Neonectria discophora (Mont.) var. discophora Mantiri & Samuels, Canad. J. Bot. 79: 339. 2001.

= Nectria tasmanica Berk. in Hooker, Flora Tasmaniae 2: 279. 1860.

= Nectria mammoidea W. Phillips & Plowr., Grevillea 3: 126. 1875.

≡ Creonectria mammoidea (W. Phillips & Plowr.) Seaver, Mycologia 1: 188. 1909.

= Nectria nelumbicola Henn., Verh. Bot. Ver. Prov. Brandenb. 40: 151. 1898.

= Nectria umbilicata Henn., Hedwigia 41: 3. 1902.

= Nectria mammoidea var. rugulosa Weese, Sitzungsber. Kaiserl. Akad. Wiss., Math.-Naturwiss. Cl., Abt. 1, 125: 552. 1916.

= Cylindrocarpon ianthothele var. majus Wollenw., Z. Parasitenk. 1: 161. 1928.

= Nectria mammoidea var. minor Reinking, Zentbl. Bakt. Parasitenk., Abt. II, 94: 135. 1936.

= Cylindrocarpon ianthothele var. minus Reinking, Zentbl. Bakt. Parasitenk., Abt. II, 94: 135. 1936.

= Creonectria discostiolata Chardón, Bol. Soc. Venez. Ci. Nat. 5: 341. 1939.

= Cylindrocarpon ianthothele var. rugulosum C. Booth, Mycol. Pap. 104: 25. 1966.

= Cylindrocarpon pineum C. Booth, Mycol. Pap. 104: 26. 1966.

Description and illustration: Chaverri et al. (2011).

Note: Representatives of the genus Thelonectria formed a monophyletic clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0), distinct from the other member genera in Clade IV even though this genus shares some morphological characters with the genera Campylocarpon and Rugonectria.

Clade V

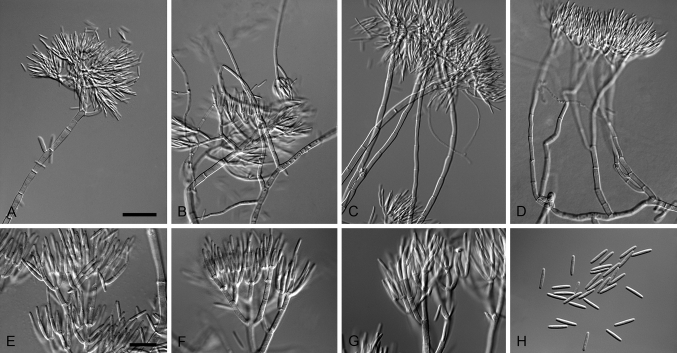

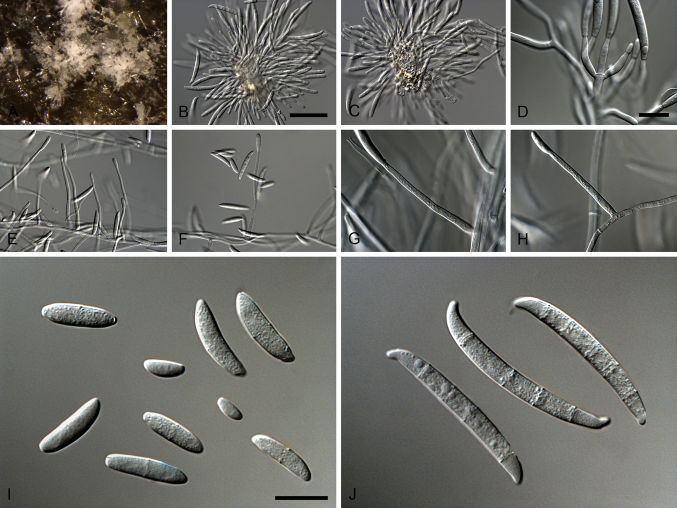

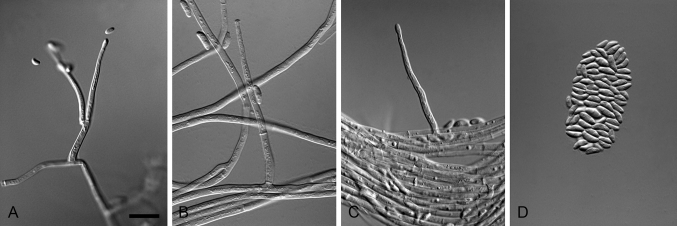

Xenogliocladiopsis Crous & W.B. Kendr., Canad. J. Bot. 72: 63. 1994. MycoBank MB27282.

Ascomatal state unknown. Conidiophores separate or aggregated in sporodochia, consisting of a stipe, a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and an avesiculate stipe extension; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth; stipe extensions septate, straight to flexuous. Conidiogenous apparatus with aseptate primary, secondary, tertiary and additional branches, each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides. Phialides cylindrical to cymbiform, hyaline, aseptate; collarette absent. Conidia hyaline, aseptate, cylindrical to fusiform with acutely rounded ends (adapted from Crous & Kendrick 1994).

Type species: Xenogliocladiopsis eucalyptorum Crous & W.B. Kendr., Canad. J. Bot. 72: 63. 1994. Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Xenogliocladiopsis eucalyptorum (ex-epitype CBS 138758). A–D. Conidiophores. E–G. Conidiogenous apparatus with cylindrical to cymbiform phialides. F. Conidia. Scale bars: A = 50 μm (apply to B–D); E = 10 μm (apply to F–H).

Materials examined: South Africa, Limpopo Province, Gold River Game Resort, Eucalyptus leaf litter, May 1991, P.W. Crous, holotype PREM 51299; Northern Cape Province, Kleinzee, on leaves of Eucalyptus sp., 27 Feb. 2009, leg. Z.A. Pretorius, isol. P.W. Crous (epitype designated here CBS H-21952, MBT198395, culture ex-epitype CBS 138758 = CPC 16271).

Notes: When Crous & Kendrick (1994) introduced the asexual genus Xenogliocladiopsis based on X. eucalyptorum, they incorrectly linked it to the Dothidiomycete sexual morph Arnaudiella eucalyptorum. Phylogenetic inference in the current study clearly shows that the genus Xenogliocladiopsis belongs to the Nectriaceae, forming a well-supported clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0) basal to Clades I–IV.

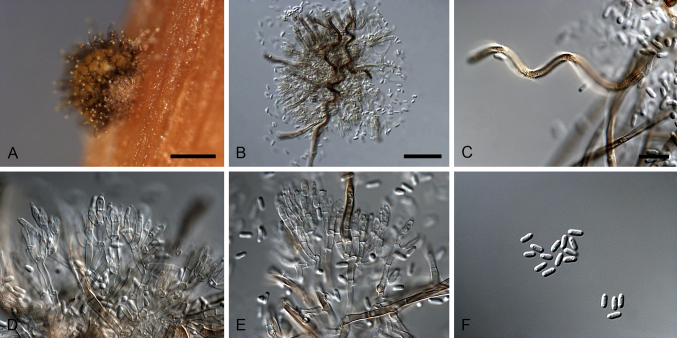

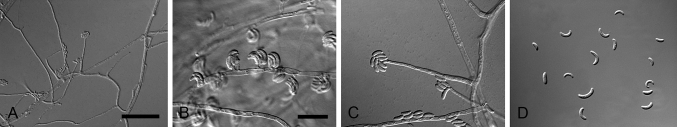

Xenogliocladiopsis cypellocarpa L. Lombard & Crous, sp. nov. MycoBank MB810166. Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Xenogliocladiopsis cypellocarpa (ex-type CBS 133814). A–C. Conidiophores. D–G. Conidiogenous apparatus with cylindrical to cymbiform phialides. H–J. Avesiculate stipe extensions. K. Conidia. Scale bars: A = 50 μm (apply to B–C); D = 10 μm (apply to E–K).

Etymology: Name derived from the plant host Eucalyptus cypellocarpa, from which it was isolated.

Ascomatal state not observed. Conidiophores hyaline, separate or aggregated in sporodochia, consisting of a stipe bearing a penicillate arrangement of fertile branches, and an avesiculate stipe extension; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 19–105 × 4–11 μm; stipe extension septate, straight to flexuous, 70–190 μm long, 2–4 μm wide at the apical septum. Conidiogenous apparatus 70–115 μm wide, and 65–105 μm long; primary branches aseptate, 15–30 × 3–7 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 10–20 × 2–6 μm; tertiary branches aseptate, 7–22 × 2–5 μm; quaternary branches and additional branches (–8) aseptate, 6–15 × 1–4 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides cylindrical to cymbiform, hyaline, aseptate, 8–11 × 1–3 μm, collarette absent. Conidia cylindrical to fusiform, rounded at both ends, straight, 8–10 × 1–2 μm (av. 9 × 1 μm).

Culture characteristics: Colonies moderately fast growing on MEA, 60–80 mm diam after 10 d at 24 °C. Surface white to pale luteous with pale luteous to yellow tuffs of sporodochia forming at the margins; aerial mycelium abundant in the centre becoming immersed towards the margins, with conidiophores forming on the aerial mycelium and on the surface at the margins. Reverse similar in colour.

Material examined: Australia, Northern territories, Darwin, Kurralong Height, on leaves of Eucalyptus cypellocarpa, 25 Apr. 2011, P.W. Crous (holotype CBS H-21951, culture ex-type CBS 133814 = CPC 19417); Queensland, Slaughter Falls, on leaves of Eucalyptus sp., 16 Jul. 2009, P.W. Crous, culture CPC 17153.

Notes: Xenogliocladiopsis cypellocarpa is introduced here as a new species in the genus Xenogliocladiopsis. This species forms shorter stipe extensions (up to 190 μm) than X. eucalyptorum (up to 220 μm), and the conidia of X. cypellocarpa are also slightly smaller than those of X. eucalyptorum (7.5–11 × 1–1.5 μm; Crous & Kendrick 1994).

Clade VI

Cylindrodendrum Bonord., Handb. allg. Mykol.: 98. 1851. MycoBank MB7873.

Ascomatal state unknown. Conidiophores initially as lateral phialides on somatic hyphae, sometimes verticillate, hyaline. Phialides monophialidic, elongate doliiform to reniform to obpyriform, with the terminal part frequently having a swollen tip, apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Conidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, 0–1-septate, with visible abscission scars (adapted from Lombard et al. 2014b).

Type species: Cylindrodendrum album Bonord., Handb. Allg. Mykol.: 48. 1851.

Description and illustrations: Lombard et al. (2014b).

Notes: Chaverri et al. (2011) suggested that the asexual morph-typified genus Cylindrodendrum could be considered as a synonym of “Cylindrocarpon”. Morphologically however, members of Cylindrodendrum more closely resemble the asexual morphs of fungal species in the genera Atractium, Cosmospora, Dialonectria, Fusicolla, Macroconia and Stylonectria, with the exception of conidium morphology (Gräfenhan et al. 2011). Based on phylogenetic inference, Cylindrodendrum isolates included in this study formed a monophyletic clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0), sister to the monophyletic clade representing Dactylonectria.

Dactylonectria L. Lombard & Crous, Phytopathol. Medit. 53: 348. 2014. MycoBank MB810142.

Ascomata perithecial, superficial, solitary or aggregated in groups, ovoid to obpyriform, dark red, becoming purple-red in KOH, smooth to finely warted, with papillate apex; without recognisable stroma. Asci clavate to narrowly clavate, 8-spored; apex rounded, with a minutely visible ring. Ascospores ellipsoidal to oblong-ellipsoidal, somewhat tapering towards the ends, medianly septate, smooth to finely warted. Conidiophores simple or aggregated to form sporodochia; simple conidiophores arising laterally or terminally from aerial mycelium, solitary to loosely aggregated, unbranched or sparsely branched, septate, bearing up to three phialides. Phialides monophialidic, more or less cylindrical, tapering slightly in the upper part towards the apex. Macroconidia cylindrical, hyaline, straight to slightly curved, 1–4-septate, apex or apical cell typically slightly bent to one side and minutely beaked, base with visible, centrally located or laterally displaced hilum. Microconidia ellipsoid to ovoid, hyaline, straight, aseptate to 1-septate, with a minutely or clearly laterally displaced hilum. Chlamydospores rarely formed, globose to subglobose, smooth but often appear rough due to deposits, thick-walled, mostly occurring in chains.

Type species: Dactylonectria macrodidyma (Halleen, et al.) L. Lombard & Crous, Phytopathol. Medit. 53: 352. 2014.

≡ Neonectria macrodidyma Halleen et al., Stud. Mycol. 50: 445. 2004.

≡ Ilyonectria macrodidyma (Halleen et al.) P. Chaverri & C. Salgado, Stud. Mycol. 68: 71. 2011.

= Cylindrocarpon macrodidymum Halleen et al., Stud. Mycol. 50: 446. 2004.

Notes: Species in the genus Dactylonectria were initially regarded as members of the genus Ilyonectria. However, phylogenetic studies (Cabral et al., 2012a, Lombard et al., 2014b), showed that the genus Ilyonectria, as originally conceived, was paraphyletic. This led to the introduction of the genus Dactylonectria to accommodate Ilyonectria species isolated from grapevines (Cabral et al., 2012a, Lombard et al., 2014b). The clade representing the genus Dactylonectria (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0) is monophyletic, and is sister to the clade representing Cylindrodendrum. Both clades are distinct from Ilyonectria.

Ilyonectria P. Chaverri & C. Salgado, Stud. Mycol. 68: 69. 2011. MycoBank MB518558.

Ascomata perithecial, superficial, solitarily or in groups, loosely attached to substrate, red, turning purple-red in KOH, globose to subglobose, or ovoid to obpyriform with a broadly conical papilla or flattened apex, scaly to slightly warted. Asci narrowly clavate or cylindrical, 8-spored; apex subtruncate, with a minutely visible ring. Ascospores ellipsoidal, 1-septate, smooth hyaline. Asexual morph cylindrocarpon-like. Conidiophores simple or complex or sporodochial. Simple conidiophores arising laterally or terminally from aerial mycelium, solitary or loosely aggregated, unbranched or sparsely branched, bearing up to three phialides. Complex conidiophores solitary or aggregated in small sporodochia, repeatedly and irregularly branched. Phialides cylindrical, tapering towards the apex. Microconidia 0–1-septate, oval to ovoid to fusiform to ellipsoid, with a minutely or clearly laterally displaced hilum, formed in heads on solitary conidiophores or as masses on sporodochia. Macroconidia straight, cylindrical, 1–3(–4)-septate, with both ends obtusely rounded, base sometimes with a visible, centrally located to laterally displaced hilum, forming flat domes of slimy masses. Chlamydospores globose to subglobose, thick-walled, intercalary or solitary, initially hyaline, becoming brown with age (adapted from Chaverri et al. 2011).

Type species: Ilyonectria destructans (Zinssm.) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous.

Description and illustration: Chaverri et al. (2011).

Notes: Representatives of the genus Ilyonectria clustered together in a well-supported clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0), distinct from the clades representing Cylindrodendrum and Dactylonectria. Chaverri et al. (2011) applied the epithet ‘radicicola’ (1963) to the type of this genus, whereas the older epithet ‘destructans’ (1918) is available. Therefore, a new combination is provided below for the type species of Ilyonectria. Furthermore, a new combination is provided for Neonectria macroconidialis, which Cabral et al. (2012a) showed to belong to this genus.

Ilyonectria destructans (Zinssm.) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous, comb. nov. MycoBank MB810954.

Basionym: Ramularia destructans Zinssm., Phytopathology 8: 570. 1918.

≡ Cylindrocarpon destructans (Zinssm.) Scholten, Netherl. J. Plant Path. 70 suppl. (2): 9. 1964.

= Cylindrocarpon radicicola Wollenw., Fus. Autogr. Del. 2: 651. 1924.

= Nectria radicicola Gerlach & L. Nilsson, Phytopathol. Z. 48: 225. 1963.

≡ Neonectria radicicola (Gerlach & L. Nilsson) Mantiri & Samuels, Canad. J. Bot. 79: 339. 2001.

≡ Ilyonectria radicicola (Gerlach & L. Nilsson) P. Chaverri & C. Salgado, Stud. Mycol. 68: 71. 2011.

Ilyonectria macroconidialis (Brayford & Samuels) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous, comb. nov. MycoBank MB810955.

Basionym: Cylindrocarpon macroconidialis Brayford & Samuels, Mycol. Res. 94: 440. 1990.

≡ Nectria radicicola var. macroconidialis Samuels & Brayford, Mycol. Res. 94: 440. 1990.

≡ Neonectria macroconidialis (Samuels & Brayford) Seifert, Phytopathology 93: 1541. 2003.

Neonectria Wollenw., Ann. Mycol. 15: 52. 1917. MycoBank MB3469.

= Chitinonectria Morelet, Bull. Soc. Sci. Nat. Archéol. Toulon & Var 178: 6. 1969.

= Heliscus Sacc., Michelia 2: 35. 1880.

Ascomata perithecial, solitary or in groups, seated on an erumpent stroma, red, turning dark red in KOH, smooth to scruffy, subglobose to broadly obpyriform, with a blunt or acute apex. Asci narrowly clavate to cylindrical, 8-spored. Ascospores ellipsoidal, smooth or finely verruculose, 1-septate, hyaline becoming pale brown with age. Paraphyses septate when present, slightly constricted at each septum. Conidiophores simple or complex forming sporodochia. Simple conidiophores solitary or loosely aggregated, unbranched or sparsely branched. Complex conidiophores irregularly branched, solitary or aggregated to form sporodochia. Phialides cylindrical, tapering towards the apex. Microconidia formed by simple conidiophores, hyaline, smooth, ellipsoidal to oblong, 0–1-septate. Macroconidia mostly formed by complex conidiophores, hyaline, smooth, straight or slightly curved towards the ends, 3–7(–9)-septate, lacking a scar or basal hilum. Chlamydospores globose to subglobose, hyaline (adapted from Chaverri et al. 2011).

Type species: Neonectria candida (Ehrenb.) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous.

Description and illustration: Chaverri et al. (2011).

Notes: The genus Neonectria is monophyletic, forming a well-supported clade (BS = 100 %, PP = 1.0), distinct from the genera included in Clade VI. A new combination is required for N. ramulariae (1917) as there is an older epithet Fusarium candidum (1818), available for this species.

Neonectria candida (Ehrenb.) Rossman, L. Lombard & Crous, comb. nov. MycoBank MB810956.

Basionym: Fusarium candidum Ehrenb., Syl. Mycol. Berol: 24. 1818.

≡ Ramularia candida (Ehrenb.) Wollenw., Phytopatology 1: 220. 1913.

≡ Cylindrocarpon ehrenbergii Wollenw., Fus. Autogr. Del.: 461. 1916.

= Fusarium obtusiusculum Sacc., Michelia 2: 297. 1881.

≡ Fusarium oxysporum var. obtusiusculum (Sacc.) Cif., Ann. Bot., Roma 16: 221. 1924.

≡ Cylindrocarpon obtusiusculum (Sacc.) U. Braun, Cryptog. Bot. 4: 113. 1993.

= Fusarium eichleri Bres., Ann. Mycol. 1: 130. 1903.

= Neonectria ramulariae Wollenw., Ann. Mycol. 15: 52. 1917.

≡ Nectria ramulariae (Wollenw.) E. Müll., Beitr. Kryptogamenfl. Schweiz 11: 634. 1962.

= Cylindrocarpon magnusianum Wollenw., Z. Parasitenk. 1: 172. 1928.

Clade VII

Chaetopsina Rambelli, Atti Accad. Sci. Ist. Bologna, Cl. Sci. Fis., Rendiconti: 5. 1956. MycoBank MB7584.

= Chaetopsinectria J. Luo & W.Y. Zhuang, Mycologia 102: 979. 2010.

Ascomata perithecial, solitary, non-stromatic, superficial, obpyriform, with an acute apex, red, becoming dark red in KOH, smooth. Asci unitunicate, clavate, 8-spored, with a simple apex or an apical ring. Ascospores ellipsoid to fusiform, 1-septate, hyaline, smooth to striate. Conidiophores erect, setiform, tapering towards acutely rounded apex, mostly flexuous, yellow-brown, turning red-brown in KOH, fertile in mid region, unbranched, verruculose, thick-walled, base bulbous. Fertile region consisting of irregularly branched dense aggregated conidiogenous cells. Conidiogenous cells ampulliform to lageniform, hyaline, smooth, mono- to polyphialidic. Conidia hyaline, smooth, guttulate, subcylindrical, aseptate, apex and base bluntly rounded, base rarely with flattened hilum (adapted from Rambelli 1956 and Luo & Zhuang 2010).

Type species: Chaetopsina fulva Rambelli, Atti Accad. Sci. Ist. Bologna, Cl. Sci. Fis. Rendiconti: 5. 1956.

= Nectria chaetopsinae Samuels, Mycotaxon 22: 18. 1985.

≡ Cosmospora chaetopsinae (Samuels) Rossman & Samuels, Stud. Mycol. 42: 119. 1999.

≡ Chaetopsinectria chaetopsinae (Samuels) J. Luo & W.Y. Zhuang, Mycologia 102: 979. 2010.

Descriptions and illustrations: Rambelli, 1956, Samuels, 1985, Luo and Zhuang, 2010.

Notes: Chaetopsinectria, a sexual genus based on Cosmospora chaetopsinae (Samuels 1985), was established by Luo & Zhuang (2010) for a group of fungi having Chaetopsina asexual morphs. We propose that the sexual genus Chaetopsinectria (2010) be suppressed in favour of asexual genus Chaetopsina (1956), which has priority by date and would require no new combinations. The clade representing Chaetopsina (BS ≥ 75 %, PP ≥ 0.95), which includes the type species, C. fulva (ex-type CBS 142.56), is closely related to but separate from the clade representing the genus Volutella. In addition, these two genera do not share any morphological characters.

Coccinonectria L. Lombard & Crous, gen. nov. MycoBank MB810176.

Etymology: Name refers to the scarlet ascomata produced by these fungi.

Ascomata perithecial, superficial, solitary or aggregated in groups, developing on old sporodochia of volutella-like asexual morphs, subovoid to subglobose, orange to orange-red to carmine red, becoming pink to purple in KOH, initially rough surface due to short, thick-walled setae, with a short papillate ostiole; perithecial wall consists of two regions; inner region composed of thin-walled, flattened, hyaline cells; outer region composed of thick-walled ellipsoid to elongated cells. Setae scattered on surface of the perithecia except at the ostiolar region, hyaline, thick-walled, straight to curved, aseptate, narrowing toward the apex. Asci unitunicate, clavate, 8-spored, apex simple, truncate with hyaline, thin-walled moniliform paraphyses between the asci. Ascospores narrowly ellipsoid to fusiform, aseptate or medianly septate, slightly constricted at the septum, hyaline, becoming dark yellow with age, finely verrucose. Conidiophores sporodochial, ochraceous to amber or light russet, with hyaline to lightly coloured aseptate setae. Conidia aseptate, hyaline, guttulate, ellipsoidal to fusiform.

Type species: Coccinonectria pachysandricola (B.O. Dodge) L. Lombard & Crous.

Notes: The sexual genus Coccinonectria is established here to accommodate fungal species previously incorrectly treated as members of the genus Pseudonectria (Rossman et al., 1999, Gräfenhan et al., 2011). Coccinonectria is distinguished from Pseudonectria by its orange to scarlet ascomata with short, thick-walled setae extending from the ascomatal surface (Dodge, 1944, Rossman et al., 1999). The latter genus is characterised by yellow to greyish yellow-green ascomata with longer setae on the ascomatal surface (Rossman et al. 1999). Phylogenetic inference also shows that the genus Coccinonectria is closely related to the genera Chaetopsina and Volutella, but clearly distinct from the genus Pseudonectria.

Coccinonectria pachysandricola (B.O. Dodge) L. Lombard & Crous, comb. nov. MycoBank MB810177.

Basionym: Pseudonectria pachysandricola B.O. Dodge, Mycologia 36: 536. 1944.

≡ Volutella pachysandricola B.O. Dodge, Mycologia 36: 536. 1944.

Description and illustrations: Dodge (1944).

Coccinonectria rusci (Lechat, Gardiennet & J. Fourn.) L. Lombard & Crous, comb. nov. MycoBank MB810179.

Basionym: Pseudonectria rusci Lechat et al., Persoonia 32: 297. 2014.

Description and illustrations: Crous et al. (2014).

Note: Coccinonectria rusci (ex-type CBS 126108) clustered in a monophyletic clade representing the genus Coccinonectria, and therefore a new combination is proposed for this species.

Pseudonectria Seaver, Mycologia 1: 48. 1909. MycoBank MB4460. emend. L. Lombard & Crous.

≡ Nectriella Sacc., Michelia 1: 51. 1877.

≡ Nectriella subgen. Notarisiella Sacc., Syll. Fung. 2: 452. 1883.

≡ Notarisiella (Sacc.) Clements & Shear, The genera of Fungi: 280. 1931.