Abstract

Frailty has been previously studied in Western countries and the urban Korean population; however, the burden of frailty and geriatric conditions in the aging populations of rural Korean communities had not yet been determined. Thus, we established a population-based prospective study of adults aged ≥ 65 years residing in rural communities of Korea between October 2014 and December 2014. All participants underwent comprehensive geriatric assessment that encompassed the assessment of cognitive and physical function, depression, nutrition, and body composition using bioimpedance analysis. We determined the prevalence of frailty based on the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) and Korean version of FRAIL (K-FRAIL) criteria, as well as geriatric conditions. We recruited 382 adults (98% of eligible adults; mean age: 74 years; 56% women). Generally, sociodemographic characteristics were similar to those of the general rural Korean population. Common geriatric conditions included instrumental activity of daily living disability (39%), malnutrition risk (38%), cognitive dysfunction (33%), multimorbidity (32%), and sarcopenia (28%), while dismobility (8%), incontinence (8%), and polypharmacy (3%) were less common conditions. While more individuals were classified as frail according to the K-FRAIL criteria (27%) than the CHS criteria (17%), the CHS criteria were more strongly associated with prevalent geriatric conditions. Older Koreans living in rural communities have a significant burden of frailty and geriatric conditions that increase the risk of functional decline, poor quality of life, and mortality. The current study provides a basis to guide public health professionals and policy-makers in prioritizing certain areas of care and designing effective public health interventions to promote healthy aging of this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Frailty, Sarcopenia, Disability, Geriatrics, Population Health, Aged

INTRODUCTION

Korea is one of the most rapidly aging developed countries (1), due to its increasing life expectancy in tandem with extremely low birth rates. According to the Statistics Korea, 13% of the population is aged 65 years or older and the aging index (ratio of the population aged 65 or older divided by the population aged 14 or younger) is 89%. Furthermore, elderly households constitute 20% of all households (2). These figures suggest that, due to the sheer number of aging individuals in Korea, health issues in older adults could potentially impose a major socioeconomic burden to the Korean society. For this reason, a systematic evaluation and plan to address highly prevalent, aging-related conditions are essential to promote quality of life and maintenance of independence in older Koreans.

Frailty is a highly prevalent, yet under-recognized condition in older adults. It is characterized by increased vulnerability to possible stressors and strongly predicts mortality and disability (3,4). Age-related changes and accumulations of subclinical and clinical disease contribute to frailty (5). In Western countries, approximately 10% of community-dwelling older adults are frail and 40% are prefrail (6), while in Korea, 10%-16% are frail and 43%-59% are prefrail in an urban population (7). However, the burden of frailty and geriatric conditions in older Koreans living in rural communities has not been established. In order to capture dynamic changes in health status and disability in older adults (8), annual follow-up examination (9) may not be sufficient. Although Korea is highly urbanized with 82% of the population living in the cities (10), 36% of older adults live in rural communities (2) and they make up greater than 20% of the population in most rural communities (11). Disparities between urban and rural populations have been documented in health status, access to health care, and resources (12). Therefore, to set the priority of public health interventions, it is crucial to determine the burden of frailty and geriatric conditions in the rural population. Nevertheless, due to limited resources and workforce trained in geriatric care, the aging of older Koreans in rural communities remains poorly understood.

With the objective of studying the burden of longitudinal changes in frailty and geriatric conditions in older Koreans in rural communities, we established the Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area (ASPRA), a population-based, prospective cohort study of older adults living in Pyeongchang County of Korea. Previously, the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea established a health care system to deliver primary care, preventive care, and home visits to rural dwellers, carried out by 1,800 Community Health Posts (CHPs) across the country under the National Healthcare Service (NHS) (13). Using this system, we collaborated with public health professionals in the CHPs of Pyeongchang County to take advantage of the regional health care delivery system for recruitment, measurements, and follow-up. In this paper, we describe our study population, measurements, and baseline examination findings on frailty, disability, and geriatric conditions in older Koreans in rural communities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Screening and recruitment of study population

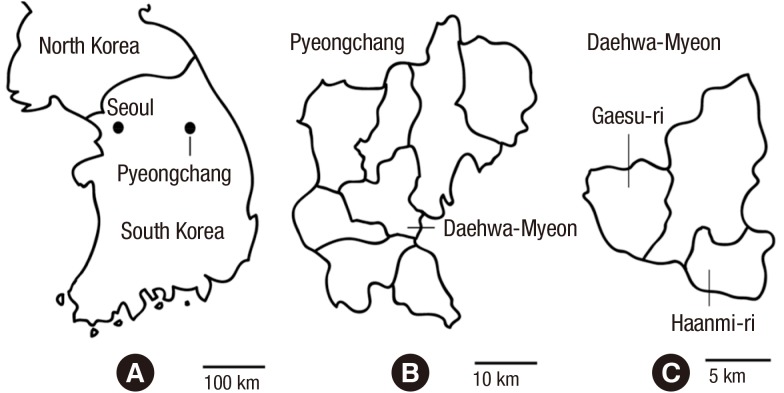

The ASPRA is a prospective cohort study of older adults who are registered in the NHS and reside in 2 rural towns (Haanmi-ri and Gaesu-ri) in Daehwa-myeon, Pyeongchang-gun, Gangwon-do, Korea. Pyeongchang-gun (County) is located 180 kilometers east of Seoul, with a total population size of 43,660 and older adults comprising 22% (Fig. 1). Due to the geographical distance to cities, the residents receive medical care almost exclusively from the regional CHPs.

Fig. 1.

Geographic location of Pyeongchang in Korea. (A) This figure shows the location of Pyeongchang-gun in relation to Seoul in Korea. (B, C) The Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area cohort was based on the 2 rural communities, Haanmi-ri and Gaesu-ri of Daehwa-Myeon in Pyeongchang-gun.

Between October and December 2014, screening and recruitment took place in Haanmi-ri and Gaesu-ri. From the NHS member roster, potentially eligible residents were identified. They received a letter or a phone call from nurses to visit the CHP for their upcoming annual health examination or vaccination. If they were not able to attend, nurses made a home visit. A resident was considered eligible if he/she was: 1) aged 65 years or older; 2) registered in the NHS; 3) ambulatory with or without an assistive device; 4) living at home at the time of the assessment; and 5) able to provide informed consent. Excluded were those who were: 1) living in a nursing home; 2) hospitalized; or 3) bed-ridden and receiving a nursing-home level care at home. Because the study presents no more than minimal risk to the participants, a verbal informed consent was obtained.

To assess whether the ASPRA cohort is representative of older Koreans in rural communities, we analyzed data from the 6th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) (14), conducted in 2013 and including 8,018 adults aged 65 years or older.

Measurements at study baseline

An experienced nurse conducted an interview, comprehensive geriatric assessment, and measurement of body composition at the regional CHP. Based on this information, we defined the key geriatric conditions as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Assessment of geriatric conditions in the Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area Cohort.

| Conditions | Definition | Follow-up schedule |

|---|---|---|

| Frailty | Frail if ≥ 3 components are present (prefrail if 1 or 2 are present; robust if none are present): | Every 3 months |

| Cardiovascular health study criteria | ||

| · Exhaustion: "moderate or most of the time during the last week" to either of the following: "I felt that everything I did was an effort" or "I could not get going." | ||

| · Low activity: physical activity level by K-PASE in the lowest quintile | ||

| · Slowness: usual gait speed < 0.8 m/sec | ||

| · Weakness: dominant handgrip strength < 26 kg for men and < 17 kg for women | ||

| · Weight loss: unintentional weight loss > 3 kg during the previous 6 months | ||

| Korean version of FRAIL criteria | Every month | |

| Fatigue: "some of the time" or "most of the time" to the following: "How much of the time during the past 4 weeks did you feel tired?" | ||

| · Resistance: positive response to the following: "By yourself and not using aids, do you have difficulty walking up 10 steps without resting?" | ||

| · Ambulation: positive response to the following: "By yourself and not using aids, do you have any difficulty walking 300 meters?" | ||

| · Illness: having > 5 diseases among the list under multimorbidity (see below) | ||

| · Loss of weight: weight loss > 5% in the past year | ||

| Multimorbidity | Having ≥ 2 chronic conditions among the following: angina, arthritis, asthma, cancer excluding minor skin cancer, chronic lung disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, heart attack, hypertension, kidney disease, stroke | Every 12 months |

| Sarcopenia | Decreased muscle mass: ASM / height2 < 7.0 kg/m2 for men and < 5.7 kg/m2 for women | Every 12 months |

| Plus, decreased physical performance: | ||

| · Decreased handgrip strength: < 26 kg for men and < 17 kg for women | ||

| · Slow gait speed: usual gait speed < 0.8 m/sec | ||

| ADL disability | Requiring assistance from another person in performing any of the following 7 activities: bathing, continence, dressing, eating, toileting, transferring, washing face and hands | Every 3 months |

| IADL disability | Requiring assistance from another person in performing any of the following 10 activities: food preparation, doing household chores, going out short distance, grooming, handling finances, laundry, managing own medications, shopping, transportation, telephone | Every 3 months |

| Cognitive dysfunction | Mini-Mental State Examination score < 24 points | Every 12 months |

| Depression | The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale score ≥ 21 points | Every 12 months |

| Dismobility | Usual gait speed < 0.6 m/sec | Every 12 months |

| Fall | History of fall in the past year | Every months |

| Malnutrition | Malnutrition if the Mini-Nutritional Assessment Short-Form score < 8 points | Every 3 months |

| At risk for malnutrition if the Mini-Nutritional Assessment Short-Form score 8-11 points | ||

| Normal nutrition if the Mini-Nutritional Assessment Short-Form score 12-14 points | ||

| Polypharmacy | Regularly taking ≥ 5 medications | Every 12 months |

| Incontinence | Positive response to the question "Can you urinate or defecate without dribbling or wetting your clothes?" | Every 12 months |

ADL, activity of daily living; ASM, appendicular skeletal muscle mass; IADL, instrumental activity of daily living; K-PASE, Korean version of Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly.

Interview

The nurse obtained information on demographic characteristics, age, sex, marital status (married, unmarried, widowed, divorced, or separated), living status (living alone, living with spouse or family, or living with others), occupation (agriculture, livestock farming, forestry, managing a store, working at a factory, or others), income (receiving Medical aid due to income < 500 USD per month), education level (no formal education, elementary school [≤ 6 years], middle or high school [7-12 years], and college or higher [> 12 years]), current drinking (yes/no), alcohol intake per week, current smoking (yes/no), cumulative lifetime smoking history (pack years), chronic conditions (angina, arthritis, asthma, cancer excluding minor skin cancer, chronic lung disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, heart attack, hypertension, kidney disease, and stroke), current use of prescription and over-the-counter medications, and history of fall in the past year.

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

The nurse measured functional status, physical activity, disability, mood, nutritional status, and frailty status using validated instruments as described follows: 1) We administered the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) (range: 0-30). Cognitive dysfunction was defined if K-MMSE score < 24 (15). 2) We used the Korean version of the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (K-PASE) (16). 3) As a physical function test, we measured handgrip strength (kg) using a dynamometer (T.K.K. 5401 Grip-D; Takei, Tokyo, Japan) and averaged two measurements from the dominant hand. Usual gait speed (m/second) was calculated from the time taken to walk four meters following one meter of unmeasured acceleration space. Slow gait was defined as < 0.8 m/second (17). Dismobility, a very slow gait, was defined as < 0.6 m/second (18). 4) To evaluate disability, using the validated scales for Koreans, we assessed dependence (i.e. requiring assistance from another person) in the following seven activities of daily living (ADL): bathing, continence, dressing, eating, toileting, transfer, and washing face and hands; and in the following ten instrumental activities of daily living (IADL): food preparation, household chores, going out short distance, grooming, handling finances, laundry, taking personal medication, shopping, using public transportation, and using the telephone (19). 5) We assessed depressive symptoms using the Korean version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies depression (CES-D) scale (range: 0-60) (20). Depression was defined if CES-D score ≥ 21 (21). 6) We defined malnutrition if the Mini-Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA-SF) score was < 8 points, and at risk for malnutrition if the MNA-SF score was 8 to 11 points (22). 7) We used two different validated frailty scales: Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) frailty criteria (exhaustion, low activity, slowness, weakness, and weight loss) (4) and the Korean version of the FRAIL scale (K-FRAIL, an acronym for fatigue, resistance, ambulation, illnesses, and loss of weight) (23,24). Each scale assigns scores from 0 to 5 and classifies participants as robust if a score of 0, prefrail if a score of 1-2, and frail if a score ≥ 3. Although both scales are validated and widely used in clinical practice and research, the K-FRAIL scale that relies on self-reported response is relatively easier to obtain compared to the CHS criteria which requires a lengthy physical activity questionnaire and a measurement of physical performance.

Measurement of body composition and sarcopenia

To assess body composition including total mass, lean mass, and fat mass, we used bioimpedance analysis (Inbody 620, InBody, Seoul, Korea) with measuring frequencies of 5, 50, and 500 kHz. The device measured the impedance of four limbs while participants were standing after overnight fasting to minimize the differences due to inter-individual fluid balance. Cut points for decreased muscle mass were a height adjusted appendicular skeletal muscle mass (ASM/height2) of < 7.0 kg/m2 for men and < 5.7 kg/m2 for women (17). This method has been previously validated in the Korean elderly population (25), with an R2 value of 0.890 compared to dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. Sarcopenia was defined according to the consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (17): ASM/height2 of < 7.0 kg/m2 for men and < 5.7 kg/m2 for women and decreased physical performance (by either handgrip strength < 26 kg for men or < 18 kg for women, or gait speed of < 0.8 m/second).

Measurements during follow-up period

At the time of writing this protocol, we plan to follow the ASPRA cohort for 5 years. During the follow-up period, we will conduct repeated interviews, geriatric assessments, and body composition measurements to determine the presence of selected geriatric conditions as listed in Table 1. We will also gather information on vital status, hospitalizations, and nursing home admission every three months by telephone interview that will be confirmed by contacting the hospital or facility.

Statistical analysis

We characterized our study population using the mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. To assess the generalizability of the ASPRA cohort, we compared demographic characteristics of the ASPRA participants with those of the nationally representative KNHANES cohort. We used stratified clustered weighting to build the standard population (4,441,345 people aged 65 years or older in urban area and 1,696,357 people aged 65 years or older in rural area) of Korea in 2013. In KNHANES, standard error (SE) was used to show variations of data; otherwise, standard deviation (SD) was used. To determine the burden of frailty and geriatric conditions in rural population, we assessed the prevalence of frailty and geriatric conditions between men and women in the ASPRA cohort, after adjusting for age using logistic regression. We compared the two frailty scales using the Kappa statistic and Spearman correlation coefficient as well as their associations with each geriatric condition. Using logistic regression, we computed the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of each geriatric condition associated with frailty versus no frailty according to each frailty scale, independently of age, sex, education level, and Medical aid status. A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea (IRB No. 2014-0988). Informed consent was waived by the board.

RESULTS

Recruitment of study population

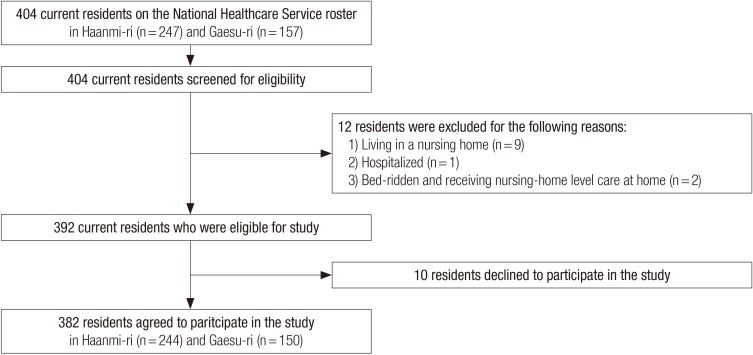

We screened 244 (98.8%) of 247 residents in Haanmi-ri and 150 (95.5%) of 157 in Gaesu-ri (Fig. 2). Of 404 residents who were screened, we excluded 12 who were institutionalized in a nursing home (n = 9), a hospital (n = 1), or bed ridden and receiving nursing care in their home (n = 2). Ten of 392 eligible residents declined to participate in the study, leaving a total of 382 (167 men and 215 women) participants.

Fig. 2.

Recruitment of the Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area Cohort. NHS, National Healthcare Service

Sociodemographic characteristics of ASPRA cohort

Sociodemographic characteristics of the ASPRA participants were compared with the nationally representative KNHANES cohort (Table 2). The mean age (74.4 years) and proportion of males (43.7%) in the ASPRA cohort were similar to those of the KNHANES population in rural as well as urban area. A unique characteristic of the ASPRA cohort was that more individuals were currently working (53.4% engaged in agriculture) and had no formal education (44.8%) compared to the older population in rural area in KNHANES (25.1% in agriculture and 22.6% with no formal education). However, the proportion of college graduates (8.4%) was similar to that in older population in urban area in KNHANES (8.4%). The proportion of individuals with income below the absolute poverty limit (monthly income < USD 500) who received Medical aid service (5.8%) was similar to the rural KNHANES population (6.2%), but lower than urban KNHANES population (10.3%). More participants were married (63.4%) in the ASPRA cohort than rural (57.6%) and urban (60.5%) KNHANES populations. The proportion of those living alone (22.8%) was smaller than that of the rural KNHANES population (26.4%).

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of the Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area Cohort and the 6th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

| Characteristics | ASPRA % or mean (SD) |

KNHANES* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rural % or mean (SE) |

Urban % or mean (SE) |

||

| Sample size | 382 | 1,696,357 | 4,441,345 |

| Age, yr | 74.4 (6.5) | 74.4 (0.4) | 73.0 (0.2) |

| Male | 43.7 | 40.9 | 41.7 |

| Currently working | 60.7 | 39.0 | 23.3 |

| Engaged in agriculture | 53.4 | 25.1 | 3.2 |

| Education level, yr | 7.8 (5.0) | NA | NA |

| No formal education | 44.8 | 22.6 | 13.9 |

| ≤ 6 yr (elementary school) | 24.6 | 45.8 | 38.5 |

| 7-12 yr (middle or high school) | 22.2 | 19.5 | 33.7 |

| > 12 yr (college or higher) | 8.4 | 2.0 | 8.4 |

| Other | 0.0 | 10.1 | 5.5 |

| Medical aid (monthly income < USD 500) | 5.8 | 6.2 | 10.3 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 63.4 | 57.6 | 60.5 |

| Widowed | 33.0 | 40.8 | 33.9 |

| Divorced or separated | 2.9 | 1.6 | 0.8 |

| Other | 0.7 | 0.0 | 4.5 |

| Living status | |||

| Living alone | 22.8 | 26.4 | 19.6 |

| Living with family | 73.0 | 63.2 | 66.4 |

| Living with others | 3.7 | 10.3 | 14.0 |

| Other | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

*Nationally representative estimates were derived by using sampling weights. NA, not available; ASPRA, Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area; KNHANES, Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; USD, United States dollar.

Prevalence of frailty and geriatric conditions

Complete data on CHS frailty criteria were available in 380 participants and K-FRAIL scale data were available in 382 participants. According to the CHS frailty criteria, 66 participants (17.4%) were frail and 200 (52.6%) were prefrail (Table 3). Of the 5 CHS frailty components, weakness (50.9%) and exhaustion (33.2%) were more common than other components (16.0%-19.9%). Among the 66 participants with frailty, 17 (25.8%) were frail without multimorbidity or disability. After adjusting for age, more women were frail or prefrail than men (22.4% vs. 10.8% for frailty; 57.0% vs. 47.0% for prefrail status, mainly due to high prevalence of exhaustion (38.6% vs. 26.3%) and weakness (66.7% vs. 30.7%) in women.

Table 3. Burden of frailty and geriatric conditions in the Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area Cohort.

| Characteristics | Men % or mean (SD) |

Women % or mean (SD) |

Total % or mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 167 | 215 | 382 |

| Age, yr | 73.7 (6.3) | 74.9 (6.6) | 74.4 (6.5) |

| Education level, yr | 7.8 (5.0) | 3.1 (4.7) | 5.1 (5.3) |

| Medical aid (monthly income < USD 500) | 5.4 | 6.0 | 5.8 |

| Living alone† | 12.6 | 30.7 | 22.8 |

| Frailty status by CHS criteria | |||

| Robust | 42.2 | 20.6 | 30.0 |

| Prefrail* | 47.0 | 57.0 | 52.6 |

| Frail* | 10.8 | 22.4 | 17.4 |

| Components of frailty by CHS criteria | |||

| Exhaustion* | 26.3 | 38.6 | 33.2 |

| Low activity | 19.8 | 20.0 | 19.9 |

| Slowness | 12.0 | 19.1 | 16.0 |

| Weakness* | 30.7 | 66.7 | 50.9 |

| Weight loss | 15.0 | 21.4 | 18.6 |

| Multimorbidity† | 23.4 | 38.6 | 31.9 |

| Sarcopenia† | 28.1 | 27.7 | 27.8 |

| ADL disability | 10.8 | 18.1 | 14.9 |

| IADL disability | 22.8 | 33.0 | 38.5 |

| Cognitive dysfunction† | 16.8 | 46.0 | 33.4 |

| Depression† | 8.0 | 18.7 | 14.1 |

| Dismobility | 5.4 | 10.7 | 8.4 |

| Fall in the past year† | 9.0 | 23.3 | 17.1 |

| At risk for malnutrition† | 30.5 | 43.7 | 37.9 |

| Polypharmacy | 3.6 | 1.9 | 2.6 |

| Incontinence | 5.4 | 10.7 | 8.4 |

*P<0.05 comparing men vs. women after adjusting for age; †P<0.01 comparing men vs. women after adjusting for age. ADL, activity of daily living; ASPRA, Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; IADL, instrumental activity of daily living; SD, standard deviation; USD, United States dollar.

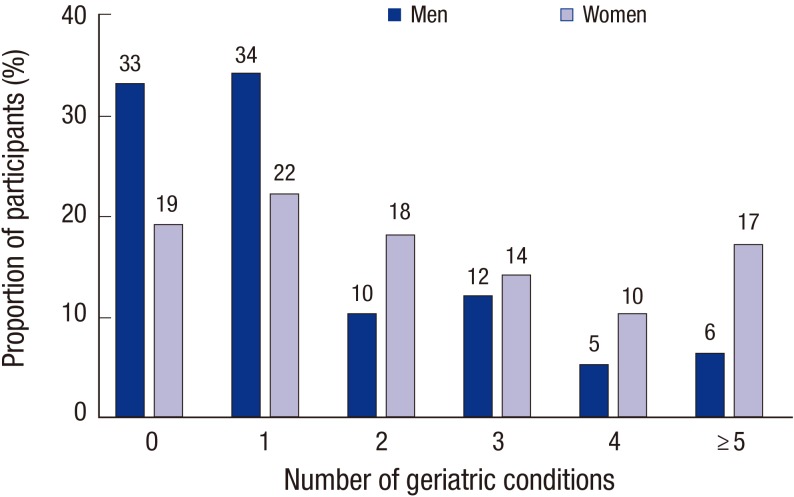

The overall burden of geriatric conditions other than frailty was high in the ASPRA cohort, particularly in women (Fig. 3); 33.5% of men and 58.6% of women had ≥ 2 geriatric conditions. The most prevalent geriatric condition was IADL disability (38.5%), followed by malnutrition risk (37.9%), cognitive dysfunction (33.4%), multimorbidity (31.9%), and sarcopenia (27.8%), whereas dismobility (8.4%), incontinence (8.4%), and polypharmacy (2.6%) were relatively uncommon (Table 3). After adjusting age, women were more likely than men to live alone and have multimorbidity, sarcopenia, cognitive dysfunction, depression, history of fall, and malnutrition risk.

Fig. 3.

Number of geriatric conditions in the Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area Cohort. The geriatric conditions considered were multimorbidity, sarcopenia, activity of daily living disability, instrumental activity of daily living disability, cognitive dysfunction, depression, dismobility, fall in the past year, at risk for malnutrition, polypharmacy, and incontinence. The definition of these conditions is given in Table 1.

Comparison of the CHS frailty criteria and K-FRAIL scale

Using the K-FRAIL scale, 105 participants (27.5%) were frail and 165 (43.2%) were prefrail. Of the five K-FRAIL components, resistance (55.0%), fatigue (46.9%), and ambulation (44.5%) were more common than loss of weight (18.6%) and illness (1.0%). The agreement between the two frailty scales was moderate (Kappa statistic: 0.41, P < 0.001; Spearman correlation coefficient: 0.64, P < 0.001).

Compared with the K-FRAIL scale, frailty according to the CHS criteria was more strongly associated with the presence of several geriatric conditions (Table 4): ADL disability (OR comparing the CHS criteria vs. K-FRAIL scale: 7.63 vs. 1.37), IADL disability (7.97 vs. 2.66), dismobility (15.8 vs. 2.04), at risk for malnutrition (4.24 vs. 2.30), polypharmacy (4.17 vs. 1.53), and incontinence (4.27 vs. 1.11). The associations with multimorbidity, sarcopenia, cognitive dysfunction, depression, and history of fall did not substantially differ between the two frailty criteria. Medical aid status (monthly income < USD 500) and living alone were associated with both definitions of frailty.

Table 4. Association between frailty and geriatric conditions in the Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area Cohort.

| Characteristics | CHS frailty criteria | K-FRAIL Scale | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-frail % |

Frail % |

OR (95% CI)* | Non-frail % |

Frail % |

OR (95% CI)* | |

| Sample size | 314 | 66 | - | 277 | 105 | - |

| Socioeconomic characteristics | ||||||

| Medical aid (monthly income < USD 500) | 4.5 | 12.1 | 2.96 (1.19-7.37) | 3.2 | 12.4 | 4.21 (1.74-10.17) |

| Living alone | 24.8 | 28.8 | 1.46 (0.81-2.66) | 20.2 | 29.5 | 1.65 (0.99-2.76) |

| Geriatric conditions | ||||||

| Multimorbidity | 30.6 | 37.9 | 1.10 (0.59-2.04) | 28.2 | 41.9 | 1.56 (0.93-2.60) |

| Sarcopenia | 21.8 | 603 | 1.91 (0.96-3.80) | 20.3 | 48.5 | 1.79 (1.01-3.20) |

| ADL disability | 8.0 | 45.5 | 7.63 (3.68-15.81) | 11.9 | 22.9 | 1.37 (0.73-2.60) |

| IADL disability | 18.5 | 74.2 | 7.97 (4.01-15.87) | 20.2 | 50.5 | 2.66 (1.55-4.56) |

| Cognitive dysfunction | 26.5 | 65.6 | 2.01 (0.99-4.09) | 25.3 | 55.4 | 1.87 (1.03-3.41) |

| Depression | 8.7 | 40.6 | 5.25 (2.55-10.83) | 5.5 | 37.3 | 7.87 (3.90-15.85) |

| Dismobility | 1.6 | 30.0 | 15.8 (5.07-49.43) | 3.7 | 12.9 | 2.04 (0.82-5.08) |

| Fall in the past year | 14.6 | 28.8 | 1.75 (0.87-3.52) | 12.7 | 28.6 | 2.09 (1.14-3.81) |

| At risk for malnutrition | 45.5 | 83.3 | 4.24 (2.03-8.83) | 44.8 | 72.4 | 2.30 (1.36-3.89) |

| Polypharmacy | 2.2 | 4.5 | 4.17 (0.67-26.02) | 2.5 | 2.9 | 1.53 (0.31-7.51) |

| Incontinence | 4.8 | 24.2 | 4.27 (1.75-10.45) | 6.9 | 12.4 | 1.11 (0.49-2.51) |

*Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of each geriatric condition comparing frail vs. non-frail status, adjusting for age, sex, education level, and Medical aid status. ADL, activity of daily living; CHS, Cardiovascular Health Study; CI, confidence interval; IADL, instrumental activity of daily living; K-FRAIL, Korean version of Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness, Loss of weight criteria; OR, odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

In the present paper, we report successful recruitment, measurements, and main findings on the burden of frailty, disability, and geriatric conditions in older Koreans living in rural communities in Korea. The objective of APSRA is to determine the longitudinal changes of health status and geriatric conditions in this underprivileged population. Ongoing follow-up assessments are expected to provide valuable data that will help us to accurately identify the most pressing aging-associated health issues and set appropriate priorities to implement effective public health interventions to promote healthy aging.

Our cohort has unique strengths that can maximize recruitment within a short period and long-term retention of participants. Geographically, the two towns in our study, Haanmi-ri and Gaesu-ri, are located in a mountainous region, distant from major cities in Korea. These conditions render the populations to be relatively stable, with less than 5% of older adults immigrating or emigrating from the area with the exception of mortality. Residents receive medical and preventive care almost exclusively from the regional CHPs under the NHS. In addition, we collaborated with public health professionals in the regional CHPs who already developed a long-term relationship with residents. A member of our investigator team met community leaders and local councilors at the town hall meetings to raise awareness and engage them in our study to uncover prevalent aging-related issues in the local community. As a result, we were able to recruit 95% of the entire population of older adults living in the study area within a 3-month period. This will help us maintain high participation rates to our frequent follow-up assessments and minimize loss to follow-up, expecting an 81.5% to 88.5% of 5 year participation rate according to the local population registry data. Because each CHP serves a central role in delivering public health interventions, our cohort can serve as a valuable testing ground for evaluating the efficacy of different interventions targeting frailty and geriatric conditions in the future.

Our analysis of baseline characteristics of the ASPRA participants offers important insights into aging-related health problems and challenges that the local community is facing. First, we identified highly prevalent geriatric conditions that affected more than a quarter of the population: IADL disability, malnutrition risk, cognitive dysfunction, multimorbidity, and sarcopenia. Second, several geriatric conditions were disproportionately more prevalent in women than men. Moreover, women were less likely than men to have received formal education and more likely to live alone. Polypharmacy was unexpectedly infrequent (2.6%), considering highly prevalent multimorbidity (27.8%) in this population. Although this might be partially attributable to incomplete recall of current medication lists by participants and their families, it raises the possibility of under-treatment of chronic conditions. Third, frailty was twice as common in women as in men, mainly caused by the higher prevalence of exhaustion and weakness in women.

We also compared two validated frailty scales in terms of their associations with each geriatric condition. The agreement and correlation between the K-FRAIL scale and CHS criteria were moderate. The K-FRAIL scale classified more participants as frail compared to the CHS criteria (27.5% vs. 17.4%), but the CHS criteria were more strongly associated with many geriatric conditions including ADL and IADL dependency, malnutrition, polypharmacy, and dismobility. This observation is in line with widespread notion and original intent by Morley that the FRAIL scale is suitable for screening possibly vulnerable older adults, rather than stratifying frailty status in already vulnerable people. On the other hand, this finding suggests that the CHS criteria may be more effective in identifying a target population who needs immediate medical intervention and support.

The prevalence of the prefrail state and frailty was similar to the estimates from a previous study on community-dwelling older adults in the urban area of Korea (7). Although direct comparison with a published report from urban population is not appropriate due to the differences in the population structure, physical activity level of the ASPRA participants was substantially higher than those living in urban areas (16), which is partially explained by the higher proportion of individuals engaged in agriculture in the ASPRA cohort. Further research to compare characteristics of frail individuals living in rural versus urban communities may allow us to investigate social and environmental determinants of aging and frailty.

Our observations provide public health professionals and policy makers with valuable information to set priorities for designing interventions and their target areas, such as support services, nutritional supplementation, exercise interventions, and health education. Social vulnerability, characterized by low socioeconomic status, lack of education, and limited access to medical services, may play an important role for geriatric conditions and frailty in our population, as previously suggested (26,27). In the past, a protein-energy nutritional supplementation improved physical function in socially vulnerable older adults with malnutrition (28). In this way, such simple, community-based interventions may be more attractive as a public health intervention in a resource-limited setting rather than hospital-based, multidisciplinary interventions.

Because our cohort is based on two rural communities in Korea, limited generalizability might be a concern. However, sociodemographic characteristics of ASPRA participants were similar to those of the representative rural Korean population, except for higher proportions of individuals engaged in agriculture and those individuals with no formal education. We also plan to expand our study base to neighboring rural communities. Currently, our study has no laboratory measurement, but we will collect selected metabolic parameters and inflammatory markers in follow-up assessments.

In conclusion, the data from the ASPRA cohort show an extensive burden of frailty and geriatric conditions in older Koreans living in rural communities. This information and future follow-up data will be of vast utility to public health professionals and policy makers to prioritize and design interventions to promote healthy aging of this vulnerable population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank our study participants and their family members in Haanmi-ri and Gaesu-ri, Pyeongchang-gun, Gangwon-do, Republic of Korea. We are also grateful to public health professionals at the Community Health Posts and County Hospital who provided administrative support.

Footnotes

Funding: The Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area was made possible by an internal fund that was personally donated by Dr. Young Soo Lee.

DISCLOSURE: Dr. Dae Hyun Kim is supported by a KL2 Medical Research Investigator Training award from Harvard Catalyst/The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH Award 1KL2 TR001100-01). Dr. Young Soo Lee, one of coauthors of this study, donated the expense for this field work but his donation made no influence on research and publication integrity. All of other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Study conception and design: Jung HW, Jang IY, Kim DH, Lee EJ, Lee YS. Field study and data collection: Jang IY, Lee CK, Cho EI, Kim WY, Chae JH. Data interpretation and statistical analysis: Jung HW, Jang IY, Kim DH, Lee EJ, Lee YS. Writing first draft: Jung HW. Revision of manuscript: Jang IY, Lee CK, Cho EI, Kim WY, Chae JH, Lee YS. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

References

- 1.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Economic Surveys: Korea 2012. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2012. p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistics Korea. Statistics Korea 2014. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2015. National statistical database. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung HW, Kim KI. Multimorbidity in older adults. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2014;18:65–71. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–56. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381:752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC. Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1487–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung HW, Kim SW, Ahn S, Lim JY, Han JW, Kim TH, Kim KW, Kim KI, Kim CH. Prevalence and outcomes of frailty in Korean elderly population: comparisons of a multidimensional frailty index with two phenotype models. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill TM. Disentangling the disabling process: insights from the precipitating events project. Gerontologist. 2014;54:533–549. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee EY, Kim HC, Rhee Y, Youm Y, Kim KM, Lee JM, Choi DP, Yun YM, Kim CO. The Korean urban rural elderly cohort study: study design and protocol. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World urbanization prospects: the 2014 revision. New York, NY: United Nations; 2014. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeon GS, Cho SH. Prevalence and social correlates of frailty among rural community-dwelling older adults. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2014;18:143–152. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chun JD, Ryu SY, Han MA, Park J. Comparisons of health status and health behaviors among the elderly between urban and rural areas. J Agric Med Community Health. 2013;38:182–194. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee CY, Cho YH. Evaluation of a community health practitioner self-care program for rural Korean patients with osteoarthritis. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2012;42:965–973. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2012.42.7.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim Y. The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES): current status and challenges. Epidemiol Health. 2014;36:e2014002. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2014002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang Y, Na DL, Hahn S. A validity study on the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in dementia patients. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 1997;15:300–308. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choe MA, Kim J, Jeon MY, Chae YR. Evaluation of the Korean version of Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (K-PASE) Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2010;16:47–59. doi: 10.4069/kjwhn.2010.16.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen LK, Liu LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Bahyah KS, Chou MY, Chen LY, Hsu PS, Krairit O, et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian working group for sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cummings SR, Studenski S, Ferrucci L. A diagnosis of dismobility--giving mobility clinical visibility: a Mobility Working Group recommendation. JAMA. 2014;311:2061–2062. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Won CW, Yang KY, Rho YG, Kim SY, Lee EJ, Yoon JL, Cho KH, Shin HC, Cho BR, Oh JR, et al. The development of Korean Activities of Daily Living (K-ADL) and Korean Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL) scale. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2002;6:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park JH, Kim KW. A review of the epidemiology of depression in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2011;54:362–369. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salvà A, Guigoz Y, Vellas B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF) J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M366–72. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.6.m366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012;16:601–608. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0084-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung HW, Yoo HJ, Park SY, Kim SW, Choi JY, Yoon SJ, Kim CH, Kim KI. The Korean version of the FRAIL scale: clinical feasibility and validity of assessing the frailty status of Korean elderly. Korean J Intern Med. 2015 doi: 10.3904/kjim.2014.331. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JH, Choi SH, Lim S, Kim KW, Lim JY, Cho NH, Park KS, Jang HC. Assessment of appendicular skeletal muscle mass by bioimpedance in older community-dwelling Korean adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;58:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curcio CL, Henao GM, Gomez F. Frailty among rural elderly adults. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woo J, Goggins W, Sham A, Ho SC. Social determinants of frailty. Gerontology. 2005;51:402–408. doi: 10.1159/000088705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim CO, Lee KR. Preventive effect of protein-energy supplementation on the functional decline of frail older adults with low socioeconomic status: a community-based randomized controlled study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:309–316. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]