Abstract

Helicobacter pylori infections are usually established in early childhood and continuously stimulate immunity, including T-helper 1 (Th1), Th17, and regulatory T-cell (Treg) responses, throughout life. Although known to be the major cause of peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer, disease occurs in a minority of those who are infected. Recently, there has been much interest in beneficial effects arising from infection with this pathogen. Published data robustly show that the infection is protective against asthma in mouse models. Epidemiological studies show that H. pylori is inversely associated with human allergy and asthma, but there is a paucity of mechanistic data to explain this. Since Th1 and Treg responses are reported to protect against allergic responses, we investigated if there were links between the human systemic Th1 and Treg response to H. pylori and allergen-specific IgE levels. The human cytokine and T-cell responses were examined using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 49 infected and 58 uninfected adult patients. Concentrations of total and allergen-specific plasma IgE were determined by ELISA and ImmunoCAP assays. These responses were analyzed according to major virulence factor genotypes of the patients’ colonizing H. pylori strains. An in vitro assay was employed, using PBMCs from infected and uninfected donors, to determine the role of Treg cytokines in the suppression of IgE. Significantly higher frequencies of IL-10-secreting CD4+CD25hi Tregs, but not H. pylori-specific Th1 cells, were present in the peripheral blood of infected patients. Total and allergen-specific IgE concentrations were lower when there was a strong Treg response, and blocking IL-10 in vitro dramatically restored IgE responses. IgE concentrations were also significantly lower when patients were infected with CagA+ strains or those expressing the more active i1 form of VacA. The systemic IL-10+ Treg response is therefore likely to play a role in H. pylori-mediated protection against allergy in humans.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, allergy, regulatory T cells, interleukin-10, IgE

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infection usually becomes established during early childhood (1), when the immune system is developing, and it persists life-long in the absence of effective treatment (2). Peptic ulceration and gastric malignancy may result; however, the infection is asymptomatic in the vast majority of cases. In recent years, there has been considerable interest in the possible beneficial effects of H. pylori infection (3–6). Protective associations between the infection and risk of atopy, asthma, and autoimmunity have been reported in epidemiological studies by us and several other groups (7–21). Not all studies have been able to demonstrate such trends, however (22–24). A meta-analysis of 700 cases and 785 controls could not prove a link between H. pylori infection and asthma risk (25), and some researchers remain skeptical (26). The most consistently observed protective associations with asthma and atopy, however, are in children (8, 16, 18, 20, 24, 27).

The incidence of atopic disease in developed countries has increased markedly over the past 50 years (28, 29). Although genetic predisposition is very important, genetic changes cannot explain this recent dramatic trend. The worldwide prevalence of H. pylori is declining, and fewer children are now infected (6, 30, 31). In developing countries, such as India and Mexico, the infection remains present in over 80% of the population, but in many developed countries, the prevalence of H. pylori is now less than 20% and it is expected to decline further (32, 33). A role for H. pylori in the “hygiene hypothesis” has been suggested, where childhood exposure to certain infections is needed for development of a healthy immune system (34, 35). Modernization has diminished exposure to many of the immunoregulatory stimuli that humans have co-evolved with, including intestinal parasites, ectoparasites, environmental bacteria, gut commensal organisms, and also H. pylori (10, 35–38). It is thought that during the past 60,000 years, human physiology has developed with the continual presence of the bacterium in the stomach (6, 39). There is growing evidence that adverse consequences may arise from a lack of exposure to H. pylori (5).

Allergies occur more commonly when certain immunological exposures are absent. Mechanisms include the stimulation of regulatory T cell (Treg) and T-helper 1 (Th1) responses to counterbalance and suppress Th2 activity in atopy (37, 38, 40–42). Although the epidemiological evidence for protective associations of H. pylori infection with atopy is compelling, it could be argued that the infection is simply a marker for other exposures with similar risk factors. The first indication of a causal relationship came from finding stronger links between childhood asthma and infection with more pathogenic CagA+ H. pylori strains (9). Direct proof of H. pylori-mediated protection in humans is still lacking, however. Arnold et al. were the first to demonstrate in a mouse model that H. pylori infection is protective against allergic asthma (43). In agreement with the human epidemiological data, these effects were stronger when the mice were infected as neonates. The mechanism was demonstrated to involve dendritic cell-mediated induction of immunosuppressive regulatory T-cells (Tregs), and the H. pylori factors important in driving this include vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), and urease (44–47).

There is a wealth of published data demonstrating that H. pylori infection induces high-level Treg, Th1, and Th17 responses in both humans and mouse models (48–53). Interferon-gamma (IFNγ)-secreting Th1 cells are associated with increased gastric inflammation and disease, whereas Tregs inhibiting inflammation are associated with reduced incidence of disease and probably contribute to the life-long persistence of H. pylori infections (32, 48). They are known to be important for suppressing autoimmunity, allergy, and inflammation (54, 55). There are several different types of Treg cells, commonly characterized as CD4+, FOXP3+, CD127low, and expressing high levels of CD25 (56). Tregs may act via a number of mechanisms, including contact-mediated suppression, or secretion of suppressive cytokines, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), IL-35, or transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) (57–59). IL-10 is known to be protective against allergy, acting via inhibition of antigen presentation, down-regulation of effector T-cell cytokine expression, and inhibition of mast cell degranulation (42, 60–62). TGFβ is also reported to play a role in protection against some animal models of allergy (63, 64). Because of the ontogeny of the immune system, H. pylori-infected children tend to have stronger Treg responses than adults (65–67). This aligns with stronger protection in the neonatally infected mouse allergy model (43) and also raises the hypothesis that the elevated frequencies of Tregs present in the circulation of H. pylori-infected humans (68) play an important role in protection against allergy.

While a great deal of convincing animal model data exist, it has frequently been difficult to prove protective effects of infections, including parasites, on clinical atopy and asthma (69). For this reason, we decided to look for more subtle effects, studying the IgE responses of non-atopic, non-asthmatic patients with carefully characterized H. pylori infection status. As reported previously (68), we found higher frequencies of IL-10-secreting Tregs in the peripheral blood of infected patients. Very low plasma IgE concentrations were present in those with the highest Treg responses, but there were no associations with the Th1 response. This indicated that higher levels of H. pylori-induced Tregs are associated with reduced markers of allergy. In vitro experiments also confirmed that blocking IL-10 (but not IFNγ or TGFβ) resulted in significantly increased IgE secretion by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from infected, but not uninfected, donors. These data indicate a role for H. pylori-induced IL-10-secreting Tregs in protection against human allergy.

Materials and Methods

All reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Ltd. (Poole, UK) unless otherwise stated.

Ethics Statement

Clinical samples were donated with informed written consent and approval from Nottingham Research Ethics Committee 2 (reference 08/H0408/195).

Volunteers and Clinical Materials

Samples were donated by 107 patients (aged 19–83 years) undergoing a routine upper gastro-intestinal endoscopy at the Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham, for a variety of indications (most commonly dyspepsia), but were otherwise healthy. Out of 107 patients, 49 donors were H. pylori-positive (14 duodenal ulcer, 9 gastric ulcer, and 26 no ulceration) and 58 were negative (none had peptic ulcers). Male-to-female ratios of these groups were 0.93 and 0.70, respectively; mean ages were 59.7 and 54.6 years, respectively. None of the patients were regularly taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or had taken antibiotics or proton pump inhibitor drugs in the preceding 2 weeks. None had clinically diagnosed asthma or allergies.

A series of biopsies were collected from the gastric antrum for determination of H. pylori infection status by urease detection, isolation and culture of the organism, and histopathology (48). DNA was purified from H. pylori isolates and PCR-genotyping carried out to ascertain cagA and vacA genotype status (70, 71). The 20-ml peripheral blood samples were collected into EDTA vacutainers. Samples of plasma were separated and stored at −80°C. PBMCs were purified by density gradient centrifugation using Histopaque1077.

Quantification of Treg and Th1-Associated Cytokine Responses of Human PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells at 1 × 106/ml in AIM V medium (Invitrogen) were placed 0.2 ml/well into 96-well plates in duplicate. A H. pylori lysate antigen prepared from six clinical isolates (48) was added at 25 μg/ml. Negative controls received no antigen, whereas positive controls received 5-μg/ml concanavalin A (conA) before incubation for 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Commercial ELISA kits (eBioscience, Hatfield, UK) were used to quantify IL-10 and TGFβ1 in culture supernatants, as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantification of Treg and Th1 cells in Human PBMCs

As described previously (48, 68, 72), 1 × 106 PBMCs were placed into culture tubes in RPMI1640 with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. H. pylori lysate antigen was added at 25 μg/ml, negative controls received no antigen, and positive controls received 20 ng/ml phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and 1 μmol/l ionomycin. Brefeldin A (BFA) was added to all tubes at 10 μg/ml before 16 h incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2.

Cells were stained with anti-CD4-phycoerythrin-Texas Red (ECD; Beckman Coulter UK Ltd., High Wycombe, UK) and anti-CD25-PE-cyanin 5 (PC5; Biolegend, Cambridge BioScience Ltd., Cambridge, UK), with either anti-CD127-phycoerythrin (PE; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-CTLA-4-PE (Beckman Coulter), or anti-GITR-PE (Biolegend) antibodies in individual tubes. Fixed and permeabilized cells were stained with anti-IL-10-PE (AbD Serotec, Oxford, UK) and anti-FOXP3-Alexa Fluor®488 antibody conjugate (Biolegend). The gating of CD25hi was set based on the positions of the FOXP3+ and CD127lo populations in CD4+ events. Alternatively, cells were stained with anti-CD4-ECD and fixed in 0.5% formaldehyde before permeabilization and staining with anti-CD69-PC5 and anti-IFNγ-FITC (Beckman Coulter).

Data on 200,000 events were acquired using a Beckman Coulter EPICS Altra flow cytometer and analyzed using Weasel version 3 (73), with reference to appropriate isotype controls.

FOXP3 and IL10 RT-qPCR

The 5 × 106 PBMCs were purified from fresh blood samples using Histopaque 1077, and total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy minikit (QIAGEN, Crawley, UK), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase with an oligo(dT) primer (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed on a Rotor-Gene 3000 (Corbett Research, Cambridge, UK) using primers described in Table 1, with a DyNAmo HS SYBR green qPCR kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, UK) as previously described (48). Amplification was over 45 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, 30 s at 62°C, and 30 s at 72°C. No template controls were included in each run, and a melting curve analysis was performed. First-stage RT-qPCR samples, produced without reverse transcriptase, were assayed in parallel. Results were analyzed using the Pfaffl method (74). FOXP3 and IL10 expression levels were normalized against GAPDH, comparing to a pooled reference sample from five Hp-negative donors to obtain a fold difference. A commercial pooled human cDNA standard (BD Biosciences) was included as a positive control in all assays.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for real-time PCR.

| Primer |

||

|---|---|---|

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

| GAPDH | CCACATCGCTCAGACACCAT | GGCAACAATATCCACTTTACCAGAGT |

| FOXP3 | CAGCACATTCCCAGAGTTCCT | GCGTGTGAACCAGTGGTAGAT |

| IL10 | GCTGGAGGACTTTAAGGGTTACCT | CTTGATGTCTGGGTCTTGGCT |

Sequences are shown in the 5′–3′ orientation.

Human IgE Assays

Plasma IgE concentrations were determined using a Human IgE ELISA Quantification Kit (Bethyl, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Optical densities were measured at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 595 nm. Concentrations of IgE were determined from a standard curve on each plate. Allergen-specific IgE assays [timothy grass pollen, birch tree pollen, and Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (house dust mite)] were carried out by the Department of Immunology, Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham, using the ImmunoCAP system (Phadia AB, Uppsala, Sweden).

In Vitro PBMC Culture and Manipulation of the Cytokine Response

A method to induce IgE synthesis in PBMC cultures was adapted from previously published studies (75–77). PBMCs from 5 H. pylori-positive and 10 H. pylori-negative healthy non-allergic donors were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 50 μg/ml transferrin, and 4 μg/ml insulin). The 200-μl aliquots containing 3 × 105 cells were added to the wells of a sterile 96-well polystyrene round-bottomed plate (Thermo Scientific). In order to induce Th2-skewed conditions, rIL-4 and sCD40L were added to the cells at final concentrations of 50 μg/ml and 100 ng/ml, respectively (Peprotech). The PBMCs were cultured for 12 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. Supernatants were then removed and stored at −80°C.

In order to observe the effects of IL-10 and TGFβ on IgE synthesis, on day 0 of the culture, 20-μl recombinant human IL-10 (rIL-10) (AbD Serotec) or rTGFβ (AbD Serotec) were added at various concentrations to appropriate wells in quadruplicate (76). The equivalent volume of medium was added to control wells. Cytokines were blocked by adding anti-IL-10 (rat IgG1 clone JES3-9D7, eBioscience) and anti-TGFβ (mouse IgG1 clone 1D11, Abcam) mAbs at varying concentrations. The respective isotype control antibodies were added at the equivalent concentrations. The 20-μg/ml JES3-9D7 has previously been shown to efficiently neutralize endogenously produced IL-10 in a similar culture system (77). The neutralization dose (ND50) of 1D11 antibody is typically 0.25–1.25 μg/ml in the presence of 1 ng/ml recombinant human TGFβ1 (78). The PBMCs were then cultured for 12 days at 37°C with 5% CO2 before collection and assay of the supernatants for IgE.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using Prism 6.00 (GraphPad Software, CA, USA). Since the data were not normally distributed, non-parametric analysis methods were used. Statistical tests of paired data were carried out using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. For unpaired data, the Mann–Whitney U-test was used. A significant difference was taken at p ≤ 0.05.

Box and whisker plots depict the medians and interquartile ranges in the boxes, with whiskers extending to the maximum and minimum points in the data.

Results

Peripheral Blood Th1 and Treg Responses in Infected and Uninfected Patients

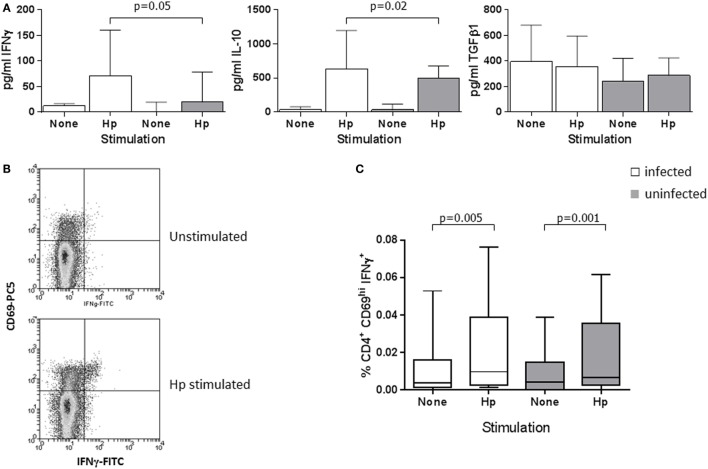

Previous work showed a high-level Treg and Th1 response in the H. pylori-infected human gastric mucosa and significantly increased numbers of CD4+CD25hi Tregs in peripheral blood (48, 68). We further investigated the circulating Treg population and determined if higher numbers of Th1 cells were also present. We began by quantifying the cytokines IFNγ, IL-10, and TGFβ1 in PBMC culture supernatants from infected and uninfected patients, and comparing the frequencies of Treg and Th1 cells by flow cytometry. PBMCs from all patients secreted IFNγ when stimulated with H. pylori lysate antigen (Hp) (Figure 1A) or the positive control mitogen conA; however, the concentrations were higher (median difference: 3.6-fold) among the Hp-stimulated supernatants from infected compared to uninfected individuals (p = 0.05). This is indicative of a systemic Th1 response to Hp infection. Similarly, there were slightly higher concentrations of IL-10 (median: 1.3-fold, p = 0.02), but there were no differences in TGFβ1 levels.

Figure 1.

Peripheral blood Th1 and Treg cytokine responses in H. pylori-infected and uninfected patients. (A) PBMCs from 13 infected patients (white bars) and 11 uninfected patients (gray bars) were cultured for 48 h in the presence of 25 μg/ml H. pylori (Hp) lysate, with medium alone as a negative control or with 20 μg/ml conA as a positive control stimulus. IFNγ, IL-10, and TGFβ1 concentrations were determined using commercial ELISA kits. Bars depict the median and error bars show the 95% confidence interval. Following conA stimulation, median concentrations from the PBMCs of infected and uninfected patients were, respectively, 1885 and 2035 pg/ml IFNγ, 375 and 393 pg/ml IL-10, and 352 and 306 pg/ml TGFβ1. Th1 cells were quantified in PBMCs from 34 infected and 24 uninfected patients using flow cytometry. (B) Example flow cytometry dot plots of gated CD4+ cells from an infected donor, stained for CD69 and IFNγ after culture of PBMCs in medium alone, or with Hp lysate antigen. Quadrant indicates the position of CD69hi IFNγ+ events, with the lower left quadrant containing both CD69-negative and -positive events. (C) The percentage of CD4+CD69hi IFNγ+ events among PBMC lymphocytes is shown following culture in medium alone (unstimulated) or with Hp lysate antigen. When stimulated with PMA and ionomycin as a positive control stimulus, the median percentages of CD4+CD69hiIFNγ+ events in PBMCs from infected and uninfected donors were 1.13 and 1.17%, respectively. The percentages of CD4+CD69hiIFNγ+ events were not significantly different between Hp-stimulated samples from infected and uninfected donors.

Using flow cytometry to quantify Hp-specific Th1 cells, we immunostained for the early activation marker CD69 (72) and analyzed cells that were activated by Hp lysate antigen (Figure 1B). Higher frequencies of CD69hiCD4+ events were obtained from the Hp-stimulated PBMCs of infected compared to uninfected donors (median: Hp+ 10.1%, Hp− 4.9%; p = 0.001), demonstrating a higher frequency of Hp-specific systemic T-cells during infection (data not shown). When cells from both infected and uninfected donors were stimulated with Hp, there was a significantly increased frequency of CD69hiCD4+IFNγ+ events compared to unstimulated PBMCs (paired analyses: infected p = 0.005; uninfected p = 0.001; Figure 1C), and similar statistically significant trends were found following PMA/ionomycin stimulation. No significant differences in the responses of cells from infected and uninfected donors were found; therefore, we could not confirm an increased frequency of Th1 cells in the peripheral blood of the infected patients. There were also no differences according to the cagA virulence genotype of the colonizing bacterial strains (not shown).

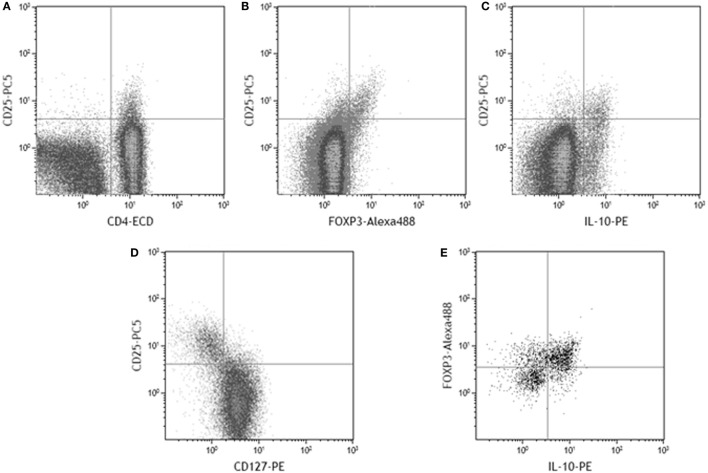

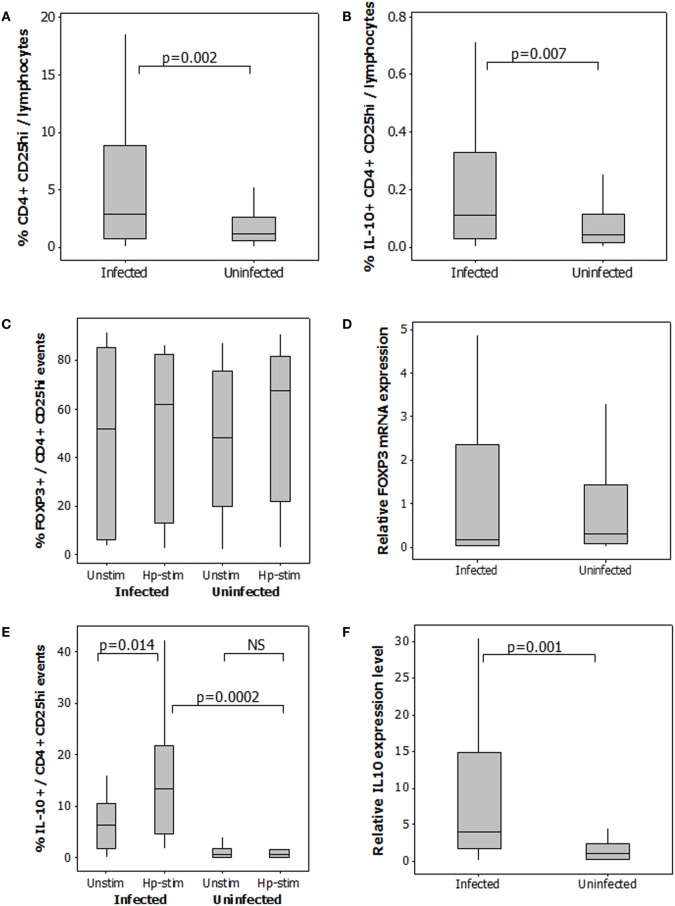

To quantify the Treg response, CD25hi staining was taken as a higher intensity of fluorescence compared to that observed for CD4 negative cells (Figure 2A), included the FOXP3+ and IL-10+ populations (Figures 2B,C), and corresponded with the CD25 staining intensity in the CD127lo population (Figure 2D). As expected, not all CD4+CD25hi events expressed FOXP3. 48–81% of gated CD4+CD25hiIL-10+ events were FOXP3+ (Figure 2E). A 2.5-fold higher median frequency of CD4+CD25hi cells (p = 0.002) was present in PBMCs from infected patients (Figure 3A). There was also a 2.5-fold increased level of IL-10+ CD4+CD25hicells (p = 0.007; Figure 3B). There was a modest 1.7-fold increase in the frequencies of CD4+CD25hiCTLA-4+ cells (p = 0.007, data not shown), but there was no difference in the frequencies of CD4+CD25hiGITR+ cells (not shown). The proportion of FOXP3+ events among CD4+CD25hi cells was not different between infected and uninfected donors, or with/without antigen stimulation (Figure 3C), and FOXP3 mRNA levels were no different when assaying PBMCs by RT-qPCR (Figure 3D). The variation in FOXP3+ cell frequencies was extremely wide within both the infected and the uninfected groups, which hampered our ability to detect statistically significant differences. The frequencies of IL-10+ and FOXP3+ CD4+CD25hi cells and the corresponding IL10 and FOXP3 transcript levels did not vary significantly according to the age or gender of the patient groups; however, those with gastric or duodenal ulcers had significantly lower frequencies of CD4+CD25hi cells than who only had gastritis (medians: 1.80 and 3.89%, respectively; p = 0.047). Similar findings were obtained when analyzing CD4+CD25hiIL-10+ data (medians: 0.10 and 0.17%, respectively; p = 0.041). In contrast, the proportion of FOXP3+ events among CD4+CD25hi cells was not significantly different with respect to peptic ulcer disease status among the infected group. Stimulating PBMCs from infected patients with Hp antigen resulted in a significant increase in the proportion of Tregs secreting IL-10 (p = 0.01), but there was no significant effect on cells from uninfected patients (Figure 3E). This indicates that H. pylori infection induces a specific IL-10-secreting peripheral blood Treg response. IL10 mRNA levels in freshly isolated PBMCs from infected patients were 3.8-fold higher than the uninfected group (p = 0.001; Figure 3F), and there was a 4.8-fold higher mRNA level in the samples from infected patients without peptic ulcer disease compared to those who had ulcers (p = 0.017). These data confirm the presence of increased numbers of IL-10+ cells in the circulation of H. pylori-infected patients, particularly when peptic ulceration is absent. Since there was an elevated systemic IL-10-secreting Treg response in infected patients, we hypothesized that as in the mouse, this could be an important mechanism behind the protective associations with allergy.

Figure 2.

Example flow cytometry dot plots to display the gating and designation of CD25hi cells among PBMC lymphocytes. CD25hi events were gated on the basis that expression is of higher intensity in CD4+ events (A). Among gated CD4+ events, the CD25hi population contains FOXP3+ events (B), IL-10+ events (C), and corresponds to the CD127lo population (D). Among gated CD4+CD25hi events, the majority of IL-10+ events were also FOXP3+ (E).

Figure 3.

Regulatory T-cells in the peripheral blood of 49 H. pylori-infected and 58 uninfected patients. The percentage of CD4+CD25hi events among gated lymphocytes (A). For determination of IL-10+CD4+CD25hi Tregs (B), PBMCs were cultured in the presence and absence of Hp lysate antigen. Median frequencies of IL-10+CD4+CD25hi events among unstimulated cells were 0.04% (uninfected donors) and 0.04% (infected donors). The proportion of CD4+CD25hi cells expressing FOXP3 (C) and IL-10 (E) was assessed in PBMCs cultured with and without Hp lysate antigen (Unstim and Hp-stim, respectively). RT-PCR was performed on freshly isolated PBMCs from 48 infected and 26 uninfected patients to quantify FOXP3 (D) and IL10 (F) mRNA expression levels. Data were normalized relative to GAPDH expression. NS = no significant difference.

Association between the Human Regulatory T-Cell and IgE Responses

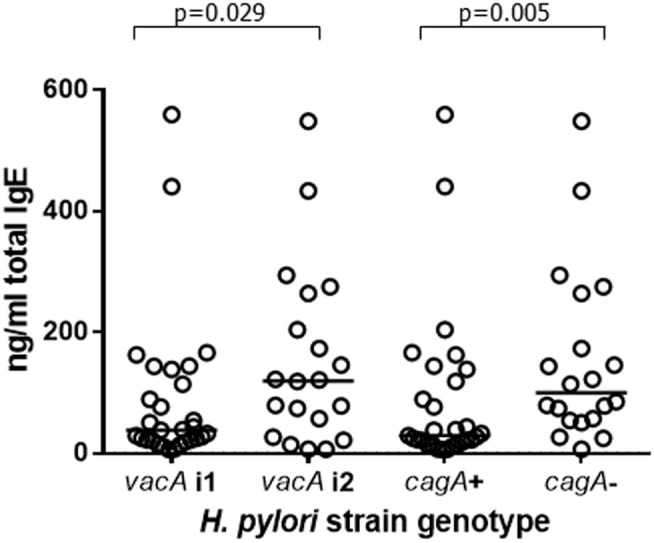

Total and allergen-specific IgE concentrations in the plasma of 49 infected and 46 uninfected patients were not significantly different (Table 2); however, among the infected group, there were differences in total IgE according to the virulence genotype of the colonizing H. pylori strains. This was important to evaluate, since presence of a strain expressing CagA has previously been reported to be associated with greater protection against asthma (9). VacA is known to be protective against allergy in mice (45). Since cagA+ strains usually also express the most active i1 form of vacA (71), we investigated how IgE levels related to these virulence factors. Apart from in five cases, the 29 cagA+ strains were also of the more active vacA i1 type. All but 5 of the 20 less pathogenic cagA− strains were typed as having the less active i2 form of vacA. We were therefore unable to pick apart the roles of these factors individually. The patients infected with the more virulent cagA+ or vacA i1 strains had threefold lower concentrations of IgE compared to those with cagA− or vacA i2 strains (Figure 4; p = 0.005 and p = 0.029, respectively). Surprisingly, however, there were no significant differences in Treg frequencies or IL-10 transcripts between those with cagA+ versus cagA– strains, and the same result was found for vacA genotypes (data not shown).

Table 2.

Total and allergen-specific IgE levels in the plasma of 49 infected and 46 uninfected patients.

| IgE measurement | Median concentration and interquartile range |

|

|---|---|---|

| H. pylori-positive | H. pylori-negative | |

| Total (ng/ml) | 58.7 (22.1–140.1) | 31.4 (9.61–133.3) |

| House dust specific (kUA/l) | 0.05 (0.03–0.13) | 0.04 (0.02–0.21) |

| Grass pollen specific (kUA/l) | 0.00 (0.00–0.03) | 0.00 (0.00–0.03) |

| Birch pollen specific (kUA/l) | 0.01 (0.00–0.02) | 0.00 (0.00–0.01) |

Figure 4.

Plasma IgE concentrations from 49 patients infected with H. pylori strains of differing virulence genotypes. Of the 29 cagA+ strains, 24 were of the i1 vacA genotype and 5 were vacA i2. Of the 20 cagA− strains, 15 were vacA i2 and 5 were of the vacA i1 genotype. Points represent the results from individuals and horizontal lines depict the median.

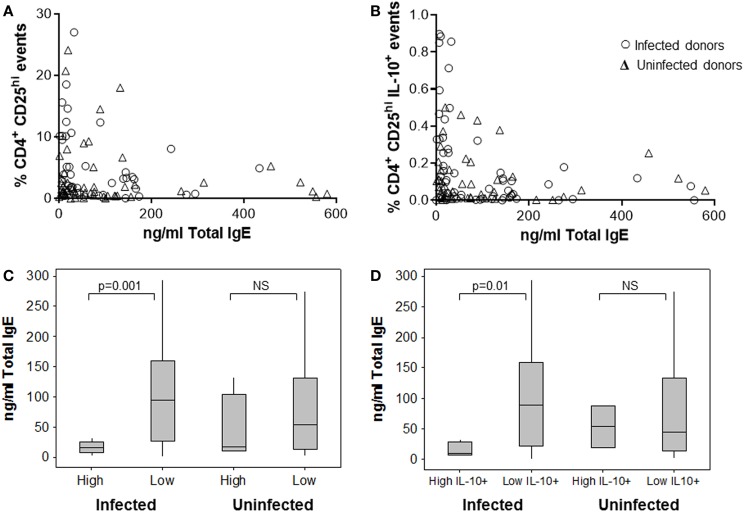

When comparing the magnitude of the Treg response with IgE levels, we observed some interesting trends. Patients with the highest frequencies of CD4+CD25hi PBMCs had the lowest total IgE concentrations. The effect was stronger among the samples from H. pylori-positive patients (Figures 5A,C), where having a high-level Treg response was more common. The data were stratified according to whether or not CD4+CD25hi cell frequencies were above or below 10%, which equated to the mean + 1 SD of all samples tested and was well above the normal range for frequencies of these cells in peripheral blood as previously reported in other studies (79, 80). Among the samples from infected patients with high CD4+CD25hi cell frequencies, there was a fivefold lower median IgE concentration, compared to those with frequencies below 10% (p = 0.001) (Figure 5C). Among the samples from infected patients with high IL-10+ CD4+CD25hi cell frequencies (>0.4%, mean + 1 SD), similarly there was a fivefold lower median IgE concentration, compared to those with low IL-10+ Treg frequencies (p = 0.01) (Figure 5B,D). There was no significant difference in the total plasma IgE concentrations of uninfected patients with high and low Treg frequencies (Figures 5C,D).

Figure 5.

Association between human peripheral blood regulatory T-cells and the IgE response. The frequency of CD4+CD25hi (A) and IL-10+ CD4+CD25hi Tregs (B) in PBMCs from 49 infected and 46 uninfected donors was assessed by flow cytometry after 15 h culture with Hp lysate antigen. This was compared to the total plasma IgE concentration for each patient. The data were divided according to whether there were high (>10%) or low frequencies of CD4+CD25hi lymphocytes (C) and high (>0.4%) or low frequencies of IL-10+CD4+CD25hi events (D) to further examine associations with total IgE concentrations. NS = no significant difference.

A significantly reduced grass (p = 0.004) and birch (p = 0.002) pollen-specific IgE concentration was present among infected patients with high frequencies of peripheral blood Treg cells (Table 3), but there were no significant differences among the uninfected group, or with regard to house dust mite-specific IgE. Similar trends were observed when comparing IgE concentrations with frequencies of IL-10+CD4+CD25hi PBMCs (data not shown). There were no significant trends when PBMC Th1 responses were compared with IgE levels (data not shown). Together, these data indicate that H. pylori infection is associated with unusually high circulating Treg levels, which could perhaps directly or indirectly suppress IgE production and influence the development of allergy.

Table 3.

Allergen-specific IgE levels in the plasma of 49 infected and 46 uninfected patients with high and lower peripheral blood CD4+CD25hi cell frequencies.

| Median concentration (kUA/l) and interquartile range |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| House dust | Grass pollen | Birch pollen | |

| H. pylori infected | NS | p = 0.004 | p = 0.002 |

| High Treg frequencies | 0.06 (0.03–0.14) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) |

| Lower Treg frequencies | 0.05 (0.04–0.13) | 0.02 (0.00–0.18) | 0.01 (0.00–0.02) |

| Uninfected | NS | NS | NS |

| High Treg frequencies | 0.03 (0.03–5.74) | 0.00 (0.00–0.04) | 0.00 (0.00–0.02) |

| Lower Treg frequencies | 0.04 (0.02–0.09) | 0.00 (0.00–0.03) | 0.00 (0.00–0.02) |

Allergen-specific IgE data were stratified according to whether the patient had a high Treg response (>10% CD4+CD25hi PBMCs) or if the frequency was below this level. A Mann–Whitney U-test analysis was performed to examine differences in the IgE responses of these groups. NS = no significant difference.

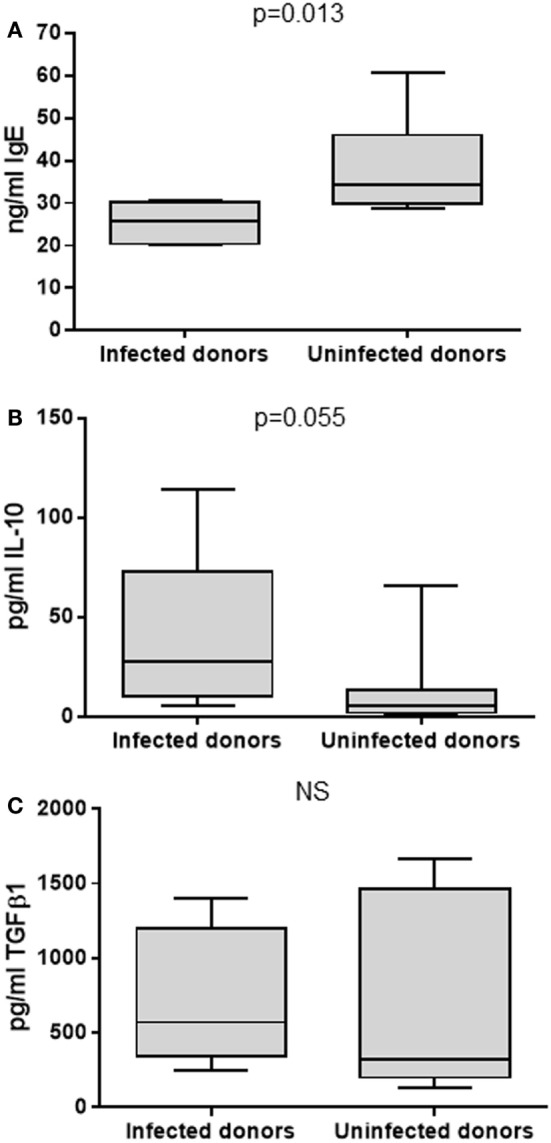

Mechanistic Experiments to Investigate the Role of Th1 and Treg Cytokines in the Suppression of IgE

To test the previously observed associations between H. pylori infection, serum IgE levels and abundance of peripheral blood Treg cells, an in vitro culture system was employed. PBMCs from 5 infected and 10 uninfected healthy donors (all without ulcers) were cultured under Th2-skewing conditions [with IL-4 and rCD40L (75)] for 12 days. Total IgE, IL-10, and TGFβ1 concentrations in the culture supernatants were then measured by ELISA. These culture conditions were used to investigate the hypothesis that PBMCs from H. pylori-positive donors would be inherently less able to respond to the Th2 stimulation compared to those from H. pylori-negative donors, possibly due to IL-10 or TGFβ inhibition of IgE production in vitro. The culture system provided an opportunity to investigate the consequence of adding or selectively blocking IL-10 and TGFβ. From the in vivo data, we hypothesized that blocking IL-10 would increase IgE production more markedly when the PBMCs were from H. pylori-positive donors. As anticipated, IgE concentrations were lower for the infected donors compared to those who were not infected (medians 25.8 and 34.2 pg/ml, respectively; p = 0.013; Figure 6A). The concentrations of IL-10 were fivefold higher in the supernatants of PBMCs from the infected donors (p = 0.055; Figure 6B), but there were no differences in the concentrations of TGFβ1 (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Culture of PBMCs under Th2-skewing conditions. PBMCs from 5 infected and 10 uninfected donors were cultured for 12 days before assaying the supernatants for total IgE (A), IL-10 (B), and TGFβ1 (C) by ELISA. NS = no significant difference.

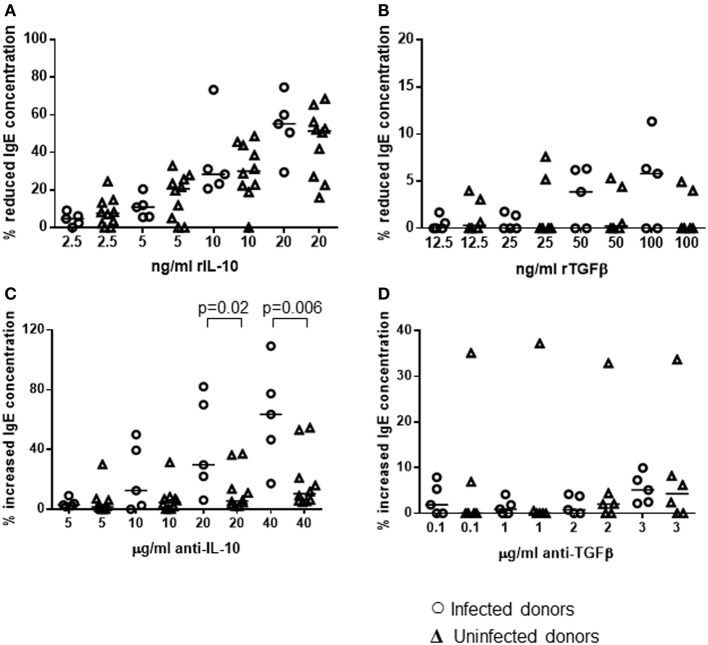

The cultures were also performed in the presence or absence of varying concentrations of recombinant IL-10, TGFβ1, or antibodies known to block the function of these cytokines. A range of concentrations was used so that we could investigate if there was a dose–response effect. Comparing each treatment to the non-treated control for each donor, the percentage decrease in total IgE resulting from the addition of recombinant cytokines was calculated. Adding the recombinant cytokines, at a range of concentrations reported previously to potently interfere with human T-helper cell activity (76, 81), caused a dose-dependent reduction in IgE secretion by PBMCs from both H. pylori-positive and -negative donors (Figures 7A,B). rIL-10 appeared to have a more potent effect than rTGFβ. Adding as little as 10 ng/ml rIL-10 resulted in a median 31% reduction in IgE concentration in the cultures compared to controls without rIL-10 (p = 0.020). Adding 20 ng/ml rIL-10 resulted in a median 52% reduction in IgE (p = 0.001). In contrast, a significantly reduced IgE concentration could only be achieved using the highest concentration of 100 ng/ml rTGFβ (5% reduction compared to no rTGFβ controls, p = 0.041). No differences in IgE response could be found between the PBMCs from H. pylori-positive and -negative donors in these assays however.

Figure 7.

Influence of recombinant IL-10 and TGFβ or their blocking antibodies on the in vitro IgE response of PBMCs from H. pylori-infected and -uninfected donors. PBMCs from 5 infected and 10 uninfected donors were cultured for 12 days under Th2-skewing conditions, with the addition of rIL-10 (A), rTGFβ (B), anti-IL-10 (C), or anti-TGFβ (D) blocking monoclonal antibodies. Equivalent volumes of medium were added to further wells as controls for recombinant cytokines; equivalent concentrations of isotype control antibodies were added as controls for the cytokine-blocking antibodies. Total IgE concentrations were assayed by ELISA and the percentage change was calculated for each individual with respect to the control cultures. Points represent the results from individuals and horizontal lines depict the median.

Adding IL-10 mAb, at a range of concentrations reported previously to block cytokine activity (77, 78), resulted in increased IgE production by PBMCs from both groups (H. pylori-positive and -negative donors), compared to cultures with the equivalent concentration of isotype control antibodies (Figure 7C). Adding anti-TGFβ had very little effect (Figure 7D). The difference in the size of the effect from IL-10 blockade between H. pylori-positive and -negative donors was statistically significant (20 μg/ml: 24%, p = 0.02; 40 μg/ml: 53%, p = 0.006). Therefore, we had confirmation that blocking IL-10, which was present at higher concentrations in the isotype control cultures of PBMCs from H. pylori-positive donors (Figure 6B), had a pronounced suppressive influence on IgE production in vitro.

Discussion

This study aimed to further investigate the inverse association between H. pylori infection and allergy in humans, and fill an important gap in current literature by exploring the potential mechanisms behind this. We were able to demonstrate a link between IL-10-secreting peripheral blood Treg cell numbers and the concentration of IgE in the plasma of infected patients, and we also showed that IL-10 produced by leukocytes from those with H. pylori played an important role in controlling IgE production in vitro.

Our previous work found an increased Treg and Th1 response in the H. pylori-infected human gastric mucosa (48) and higher frequencies of Tregs in the peripheral blood of infected patients (68). These cell types have previously been implicated in the suppression of Th2 responses and allergy. We hypothesized that increased levels of Treg cells and/or Th1 cells in the circulation influence immune responses at extra-gastric sites in the body and may play a role in preventing an elevated IgE response. Initially, we compared the IFNγ, IL-10, and TGFβ1 responses of PBMCs to stimulation with Hp lysate antigen. Enhanced concentrations of IFNγ [as shown previously (82)] and IL-10 were found in the PBMC supernatants from infected patients, indicating that peripheral blood Th1 and Treg responses were increased. Cells from both H. pylori-positive and -negative patients secreted IFNγ and IL-10 in response to Hp lysate antigens, indicating that the response was not antigen specific. Flow cytometry was therefore used to determine whether increased frequencies of Th1 and Treg cells were present in the blood of infected patients.

Our experiments employed detection of CD69 expression, an early activation marker (83), as a tool to identify IFNγ+CD4+ Th1 cells that were responsive to Hp stimulation. This could be a consequence of antigen-specific reactivation of memory cells or T-cell receptor-independent immune activation. In agreement with the work of Lundgren et al. (84), peripheral blood CD4+ cells secreted IFNγ when stimulated with Hp antigen; however, there were no differences between the samples from infected and uninfected donors. The response is therefore unlikely to be due to reactivation of H. pylori-specific memory cells, but could arise because of shared or cross-reactive antigens with other bacteria, or because ligands for pattern recognition receptors were present in the antigen preparation (85).

In agreement with our previous work, and that of others, we found higher levels of CD4+CD25hi lymphocytes among PBMCs from the infected donors (68, 84). It was necessary to determine if these populations could be classed as Tregs by using a selection of cellular markers, and a large proportion of the CD4+CD25hi events expressed FOXP3 and/or IL-10. Since enhanced FOXP3+ Treg levels are present in the infected human gastric mucosa (48, 49, 51), we were surprised to find no difference in the frequencies of FOXP3+CD4+CD25hi PBMCs, but this result was confirmed using RT-qPCR. FOXP3 is not a completely reliable marker for human Tregs, since its expression can be induced in activated cells that lack suppressive function, and not all Treg populations are FOXP3+ (56, 86). Interestingly, we were able to show increased levels of CD4+CD25hiIL-10+ lymphocytes in the PBMCs of infected patients. When stimulating PBMCs with Hp lysate antigen, a higher proportion of the Tregs from H. pylori-positive patients expressed IL-10. There was no effect on the CD4+CD25hi population from uninfected patients, indicating the presence of a H. pylori-specific circulating Treg response. We were also able to confirm this by RT-qPCR, where higher levels of IL10 mRNA were found in PBMCs from the infected patients. This agrees with several previous reports of H. pylori-specific IL-10-secreting CD4+ cells in the blood (87–89). We previously found increased levels of IL-10+FOXP3+ Tregs in the H. pylori-infected human gastric mucosa, cellular FOXP3 expression was of high level and could be confirmed by RT-qPCR (48). Our data suggest that slightly different Treg populations may be present in the blood, and these could include a higher proportion of FOXP3− subtypes, such as Tr1 cells (which are IL-10+) (90) and FOXA1+ cells (associated with IFNβ responses) (91), since H. pylori stimulates the production of IFNβ by gastric epithelial cells (92). Recently, we were able to show that significantly higher proportions of peripheral blood Tregs from infected patients expressed the chemokine receptor CCR6 and that high concentrations of its ligand, CCL20, were present in infected human gastric mucosal tissue. The CCL20–CCR6 axis was shown to play an important role in the migration of Tregs to the infected gastric mucosa (68). Some studies have suggested that CCL20/CCR6 interactions are important in the development of Th2 responses and allergy (93, 94). It may therefore be the case that CCR6+ Tregs in the circulation of those infected with H. pylori are more capable of migration to the site of allergic responses.

Increased concentrations of IL-10 (but not IFNγ) are present in the serum of H. pylori-infected patients (95), and we have found high levels of Hp-specific IL-10-secreting Tregs in the circulation. This makes it a likely possibility that such cells could cause bystander suppression of other unrelated extra-gastric immune responses via IL-10 secretion. Since the major function of Tregs is to prevent autoimmune disease caused by an overzealous immune response (58), we hypothesized that the H. pylori-induced Treg response is involved in protection against allergy. Increased IL-10 responses have been postulated as a mechanism behind H. pylori-mediated protection from allergy in humans (96); however, Cam et al. found that PBMC IL-10 production was not influenced by H. pylori status or presence of atopy in children (97). Because of these controversies, we examined the relationship between plasma IgE concentrations and the frequency of IL-10+ CD4+CD25hi Tregs among PBMCs in infected and uninfected individuals. No significant differences in IgE concentrations (total or antigen specific) were found between the groups of infected and uninfected donors. This may be due to collecting samples from patients with GI symptoms, where only a small proportion had concentrations of serum IgE above the normal range, and none had reported that they suffered from allergies or asthma. When associations between Treg frequency and plasma IgE concentration were examined, as anticipated from the literature (76, 98), higher Treg responses coincided with low IgE levels. This trend was exaggerated among the H. pylori-positive group, which contained more individuals with high Treg frequencies accompanied by lower concentrations of total, grass pollen-, and birch pollen-specific IgE. The trend was not statistically significant among the uninfected group, indicating that stronger Treg responses in H. pylori infection may suppress IgE levels. We acknowledge that as the samples were collected throughout the year, the data are likely to be confounded by seasonal variation in exposure to pollens. Regardless of this, we were able to detect significant differences in the relationship between IgE and circulating Tregs between the infected and uninfected groups.

Blaser et al. reported stronger protective associations between childhood asthma and more virulent CagA+ H. pylori infections (7, 9). Our data supported this finding, since those infected with cagA+ strains had threefold lower plasma IgE concentrations. A number of H. pylori virulence factors have been reported to influence the development of allergy in mouse models, including H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP) (a potent stimulator of Th1 responses) and VacA (known to interfere with antigen presentation and to inhibit T-cell activation; also proposed to stimulate Tregs) (45, 99, 100). Strains which express the active i1 form of VacA are usually also cagA+ and those expressing the i2 form of VacA are usually cagA− (101). This was indeed true in 39/49 of our clinical isolates and, since the vacA types also followed the same trend in the IgE data, we consider it likely that the reported stronger protection from CagA+ strains against childhood asthma could actually have been driven by VacA, with CagA acting as a marker for this. We previously found elevated IL-10 responses in the cagA+-infected gastric mucosa (48), but in the present study, we could not find a corresponding significant difference in the peripheral blood (data not shown). It has been suggested that cagA+ strains may elicit an increased gastric Treg response to modulate the heightened inflammation, but that there is also a pronounced effect on the migration of Tregs, which may have an impact on the populations found in peripheral blood (68, 102).

We performed experiments with an in vitro culture system to investigate the impact of IL-10 and TGFβ on IgE production in a well-controlled manner. The healthy donors who provided us with blood samples did not have different plasma IgE concentrations according to their H. pylori status (data not shown); therefore, these experiments allowed us to investigate the potential for their PBMCs to be influenced by a Th2-skewing treatment and produce IgE in vitro. The cells from the uninfected donors secreted significantly higher IgE concentrations, while producing markedly lower levels of IL-10. This implies that there were marked differences in the PBMC cell populations of infected and uninfected donors and is in agreement with the increased frequencies of IL-10-secreting Tregs among those with H. pylori. When rIL-10 was added to the cultures, in accordance with previous data, the PBMCs produced lower amounts of IgE (76). This occurred whether the cells were from infected or uninfected donors. When IL-10 blocking antibody was added, however, there was a significantly increased IgE response, which was especially marked when PBMCs were from infected donors. There were minimal effects from rTGFβ1 or TGFβ antibody blockade. These experiments demonstrate the important role of the H. pylori-induced IL-10 response in controlling IgE production.

We acknowledge that a weakness in this study comes from the fact that the blood samples did not come from allergic or atopic patients; however, we have gathered some interesting novel data that confirm and extend previous research on this topic. It is not possible to use an in vivo interventional approach in humans to study the role of IL-10 in the protective mechanism behind H. pylori-mediated protection from allergy. Our in vitro culture system provided some important clues, however, and enables us to move the project forward. Since we wish to understand the effects of H. pylori in protection against allergy, the best approach would be to perform an interventional study investigating the effects of antibiotic eradication therapy on allergic parameters and peripheral blood Treg frequencies. This would include looking for differences in IL-10-expressing populations in particular.

In summary, we demonstrated the presence of an increased frequency of regulatory T-cells in the peripheral blood of H. pylori-infected individuals. These cells tended to express IL-10, and high-level responses were associated with reduced plasma IgE concentrations. Using an in vitro culture system, we showed for the first time that PBMCs from H. pylori-infected donors had an enhanced ability to minimize IgE responses, acting in part via IL-10 since there was a 50% increase in IgE when IL-10 was blocked. Further in vitro work (not shown) found that CD4+CD25hi cells, purified from PBMCs of infected and uninfected donors using magnetic bead separation, were able to suppress proliferation and IFNγ production by CD4+CD25– effector T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/28 beads. This confirms that the cells have a regulatory function, and we are currently working to evaluate whether Tregs from infected individuals have any enhancement in suppressive activity. We also aim to carry out further experiments to elucidate the mechanisms, investigating the types of Tregs responsible (e.g., Tr1 and FOXA1+ cells), and are planning to investigate whether H. pylori exerts a long-lasting influence on the Treg and IL-10 response from early life, or if the immunological effects require continual life-long presence of the infection in the gastric mucosa. Understanding these concepts is going to be of paramount importance, considering the diminishing prevalence of H. pylori around the world, and newly reported hopes for an effective vaccine (103, 104).

Author Contributions

KH, DL, AG, RK, JA, and KR designed the experiments; KH, DL, AG, RK, JW, WT, JR, ES, and KR carried out the experimental work; KH, DL, AG, RK, ES, KK, and KR analyzed the data; and KH, DL, KK, and KR wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. S. Martin and Ms. T. Patel for arranging the human IgE tests, and Mrs. N. Lane for technical assistance.

Funding

Supported by funding from the Medical Research Council [project grant G0601170, Strategic Skills Award G1000401, a Ph.D. studentship for KH, and a Clinical Research Training Fellowship for ES (G0701377)], Nottingham University Hospitals Charities, and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), through the NIHR Biomedical Research Unit in Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and the University of Nottingham. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

BFA, brefeldin A; conA, concanavalin A; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4; ECD, phycoerythrin-Texas Red; GITR, glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PC5, phycoerythrin cyanin 5.1; PE, phycoerythrin; PMA, phorbol myristate acetate; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-beta; Treg, regulatory T-cell.

References

- 1.Dunn BE, Cohen H, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori. Clin Microbiol Rev (1997) 10(4):720–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zevering Y, Jacob L, Meyer TF. Naturally acquired human immune responses against Helicobacter pylori and implications for vaccine development. Gut (1999) 45(3):465–74. 10.1136/gut.45.3.465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Elios MM, de Bernard M. To treat or not to treat Helicobacter pylori to benefit asthma patients. Expert Rev Respir Med (2010) 4(2):147–50. 10.1586/ers.10.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold IC, Hitzler I, Muller A. The immunomodulatory properties of Helicobacter pylori confer protection against allergic and chronic inflammatory disorders. Front Cell Infect Microbiol (2012) 2:10. 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson K. Helicobacter pylori-mediated protection against extra-gastric immune and inflammatory disorders: the evidence and controversies. Diseases (2015) 3(2):34–55. 10.3390/diseases3020034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atherton JC, Blaser MJ. Coadaptation of Helicobacter pylori and humans: ancient history, modern implications. J Clin Invest (2009) 119(9):2475–87. 10.1172/JCI38605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reibman J, Marmor M, Filner J, Fernandez-Beros ME, Rogers L, Perez-Perez GI, et al. Asthma is inversely associated with Helicobacter pylori status in an urban population. PLoS One (2008) 3(12):e4060. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori colonization is inversely associated with childhood asthma. J Infect Dis (2008) 198(4):553–60. 10.1086/590158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Inverse associations of Helicobacter pylori with asthma and allergy. Arch Intern Med (2007) 167(8):821–7. 10.1001/archinte.167.8.821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matricardi PM, Rosmini F, Riondino S, Fortini M, Ferrigno L, Rapicetta M, et al. Exposure to foodborne and orofecal microbes versus airborne viruses in relation to atopy and allergic asthma: epidemiological study. BMJ (2000) 320(7232):412–7. 10.1136/bmj.320.7232.412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kosunen TU, Hook-Nikanne J, Salomaa A, Sarna S, Aromaa A, Haahtela T. Increase of allergen-specific immunoglobulin E antibodies from 1973 to 1994 in a Finnish population and a possible relationship to Helicobacter pylori infections. Clin Exp Allergy (2002) 32(3):373–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01330.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linneberg A, Ostergaard C, Tvede M, Andersen LP, Nielsen NH, Madsen F, et al. IgG antibodies against microorganisms and atopic disease in Danish adults: the Copenhagen Allergy Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2003) 111(4):847–53. 10.1067/mai.2003.1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pessi T, Virta M, Adjers K, Karjalainen J, Rautelin H, Kosunen TU, et al. Genetic and environmental factors in the immunopathogenesis of atopy: interaction of Helicobacter pylori infection and IL4 genetics. Int Arch Allergy Immunol (2005) 137(4):282–8. 10.1159/000086421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seiskari T, Kondrashova A, Viskari H, Kaila M, Haapala AM, Aittoniemi J, et al. Allergic sensitization and microbial load – a comparison between Finland and Russian Karelia. Clin Exp Immunol (2007) 148(1):47–52. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03333.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li W, Minohara M, Su JJ, Matsuoka T, Osoegawa M, Ishizu T, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection is a potential protective factor against conventional multiple sclerosis in the Japanese population. J Neuroimmunol (2007) 184(1–2):227–31. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amberbir A, Medhin G, Erku W, Alem A, Simms R, Robinson K, et al. Effects of Helicobacter pylori, geohelminth infection and selected commensal bacteria on the risk of allergic disease and sensitization in 3-year-old Ethiopian children. Clin Exp Allergy (2011) 41(10):1422–30. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03831.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook KW, Crooks J, Hussain K, O’Brien K, Braitch M, Kareen H, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection reduces disease severity in an experimental model of multiple sclerosis. Front Microbiol (2015) 8:52. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amberbir A, Medhin G, Abegaz WE, Hanlon C, Robinson K, Fogarty A, et al. Exposure to Helicobacter pylori infection in early childhood and the risk of allergic disease and atopic sensitization: a longitudinal birth cohort study. Clin Exp Allergy (2014) 44(4):563–71. 10.1111/cea.12289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imamura S, Sugimoto M, Kanemasa K, Sumida Y, Okanoue T, Yoshikawa T, et al. Inverse association between Helicobacter pylori infection and allergic rhinitis in young Japanese. J Gastroenterol Hepatol (2010) 25(7):1244–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06307.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khamechian T, Movahedian AH, Ebrahimi Eskandari G, Heidarzadeh Arani M, Mohammadi A. Evaluation of the correlation between childhood asthma and Helicobacter pylori in Kashan. Jundishapur J Microbiol (2015) 8(6):e17842. 10.5812/jjm.8(6)2015.17842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Constantinescu CA, Constantinescu EM. Is there a difference in the incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with some chronic diseases? Roum Arch Microbiol Immunol (2014) 73(3–4):65–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodner C, Anderson WJ, Reid TS, Godden DJ. Childhood exposure to infection and risk of adult onset wheeze and atopy. Thorax (2000) 55(5):383–7. 10.1136/thorax.55.5.383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fullerton D, Britton JR, Lewis SA, Pavord ID, McKeever TM, Fogarty AW. Helicobacter pylori and lung function, asthma, atopy and allergic disease – a population-based cross-sectional study in adults. Int J Epidemiol (2009) 38(2):419–26. 10.1093/ije/dyn348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holster IL, Vila AM, Caudri D, den Hoed CM, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ, et al. The impact of Helicobacter pylori on atopic disorders in childhood. Helicobacter (2012) 17(3):232–7. 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00934.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Bi Y, Zhang L, Wang C. Is Helicobacter pylori infection associated with asthma risk? A meta-analysis based on 770 cases and 785 controls. Int J Med Sci (2012) 9(7):603–10. 10.7150/ijms.4970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori update: gastric cancer, reliable therapy, and possible benefits. Gastroenterology (2015) 148(4):719.e–31.e. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zevit N, Balicer RD, Cohen HA, Karsh D, Niv Y, Shamir R. Inverse association between Helicobacter pylori and pediatric asthma in a high-prevalence population. Helicobacter (2011) 17(1):30–5. 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00895.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austin JB, Kaur B, Anderson HR, Burr M, Harkins LS, Strachan DP, et al. Hay fever, eczema, and wheeze: a nationwide UK study (ISAAC, international study of asthma and allergies in childhood). Arch Dis Child (1999) 81(3):225–30. 10.1136/adc.81.3.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bloomfield SF, Stanwell-Smith R, Crevel RW, Pickup J. Too clean, or not too clean: the hygiene hypothesis and home hygiene. Clin Exp Allergy (2006) 36(4):402–25. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02463.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malaty HM. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol (2007) 21(2):205–14. 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mentis A, Lehours P, Megraud F. Epidemiology and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter (2015) 20(Suppl 1):1–7. 10.1111/hel.12250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White JR, Winter JA, Robinson K. Differential inflammatory response to Helicobacter pylori infection: etiology and clinical outcomes. J Inflamm Res (2015) 8:137–47. 10.2147/JIR.S64888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grad YH, Lipsitch M, Aiello AE. Secular trends in Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence in adults in the United States: evidence for sustained race/ethnic disparities. Am J Epidemiol (2012) 175(1):54–9. 10.1093/aje/kwr288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheikh A, Strachan DP. The hygiene theory: fact or fiction? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (2004) 12(3):232–6. 10.1097/01.moo.0000122311.13359.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rook GA. Hygiene hypothesis and autoimmune diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol (2012) 42(1):5–15. 10.1007/s12016-011-8285-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rook GA. Regulation of the immune system by biodiversity from the natural environment: an ecosystem service essential to health. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2013) 110(46):18360–7. 10.1073/pnas.1313731110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trujillo C, Erb KJ. Inhibition of allergic disorders by infection with bacteria or the exposure to bacterial products. Int J Med Microbiol (2003) 293(2–3):123–31. 10.1078/1438-4221-00257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Araujo MI, Hoppe BS, Medeiros M, Jr, Carvalho EM. Schistosoma mansoni infection modulates the immune response against allergic and auto-immune diseases. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz (2004) 99(5 Suppl 1):27–32. 10.1590/S0074-02762004000900005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oertli M, Muller A. Helicobacter pylori targets dendritic cells to induce immune tolerance, promote persistence and confer protection against allergic asthma. Gut Microbes (2012) 3(6):566–71. 10.4161/gmic.21750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalliomaki M, Salminen S, Poussa T, Arvilommi H, Isolauri E. Probiotics and prevention of atopic disease: 4-year follow-up of a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (2003) 361(9372):1869–71. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13490-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mortimer K, Brown A, Feary J, Jagger C, Lewis S, Antoniak M, et al. Dose-ranging study for trials of therapeutic infection with Necator americanus in humans. Am J Trop Med Hyg (2006) 75(5):914–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faith A, Singh N, Farooque S, Dimeloe S, Richards DF, Lu H, et al. T cells producing the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 regulate allergen-specific Th2 responses in human airways. Allergy (2012) 67(8):1007–13. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02852.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arnold IC, Dehzad N, Reuter S, Martin H, Becher B, Taube C, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents allergic asthma in mouse models through the induction of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest (2011) 121(8):3088–93. 10.1172/JCI45041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oertli M, Sundquist M, Hitzler I, Engler DB, Arnold IC, Reuter S, et al. DC-derived IL-18 drives Treg differentiation, murine Helicobacter pylori-specific immune tolerance, and asthma protection. J Clin Invest (2012) 122(3):1082–96. 10.1172/JCI61029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oertli M, Noben M, Engler DB, Semper RP, Reuter S, Maxeiner J, et al. Helicobacter pylori gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and vacuolating cytotoxin promote gastric persistence and immune tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2013) 110(8):3047–52. 10.1073/pnas.1211248110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koch KN, Hartung ML, Urban S, Kyburz A, Bahlmann AS, Lind J, et al. Helicobacter urease-induced activation of the TLR2/NLRP3/IL-18 axis protects against asthma. J Clin Invest (2015) 125(8):3297–302. 10.1172/JCI79337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Engler DB, Reuter S, van Wijck Y, Urban S, Kyburz A, Maxeiner J, et al. Effective treatment of allergic airway inflammation with Helicobacter pylori immunomodulators requires BATF3-dependent dendritic cells and IL-10. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2014) 111(32):11810–5. 10.1073/pnas.1410579111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robinson K, Kenefeck R, Pidgeon EL, Shakib S, Patel S, Polson RJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori-induced peptic ulcer disease is associated with inadequate regulatory T cell responses. Gut (2008) 57(10):1375–85. 10.1136/gut.2007.137539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rad R, Brenner L, Bauer S, Schwendy S, Layland L, da Costa CP, et al. CD25+/Foxp3+ T cells regulate gastric inflammation and Helicobacter pylori colonization in vivo. Gastroenterology (2006) 131(2):525–37. 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raghavan S, Fredriksson M, Svennerholm AM, Holmgren J, Suri-Payer E. Absence of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells is associated with a loss of regulation leading to increased pathology in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice. Clin Exp Immunol (2003) 132(3):393–400. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02177.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lundgren A, Stromberg E, Sjoling A, Lindholm C, Enarsson K, Edebo A, et al. Mucosal FOXP3-expressing CD4+ CD25high regulatory T cells in Helicobacter pylori-infected patients. Infect Immun (2005) 73(1):523–31. 10.1128/IAI.73.1.523-531.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaparakis M, Laurie KL, Wijburg O, Pedersen J, Pearse M, van Driel IR, et al. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells modulate the T-cell and antibody responses in Helicobacter-infected BALB/c mice. Infect Immun (2006) 74(6):3519–29. 10.1128/IAI.01314-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bamford KB, Fan X, Crowe SE, Leary JF, Gourley WK, Luthra GK, et al. Lymphocytes in the human gastric mucosa during Helicobacter pylori have a T helper cell 1 phenotype. Gastroenterology (1998) 114(3):482–92. 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70531-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Belkaid Y, Rouse BT. Natural regulatory T cells in infectious disease. Nat Immunol (2005) 6(4):353–60. 10.1038/ni1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson C, Powrie F. Regulatory T cells. Curr Opin Pharmacol (2004) 4(4):408–14. 10.1016/j.coph.2004.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Santegoets SJ, Dijkgraaf EM, Battaglia A, Beckhove P, Britten CM, Gallimore A, et al. Monitoring regulatory T cells in clinical samples: consensus on an essential marker set and gating strategy for regulatory T cell analysis by flow cytometry. Cancer Immunol Immunother (2015) 64(10):1271–86. 10.1007/s00262-015-1729-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vignali D. How many mechanisms do regulatory T cells need? Eur J Immunol (2008) 38(4):908–11. 10.1002/eji.200738114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caton AJ, Weissler KA. Regulatory cells in health and disease. Immunol Rev (2014) 259(1):5–10. 10.1111/imr.12178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shevach EM, Thornton AM. tTregs, pTregs, and iTregs: similarities and differences. Immunol Rev (2014) 259(1):88–102. 10.1111/imr.12160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McGuirk P, Higgins SC, Mills KH. The role of regulatory T cells in respiratory infections and allergy and asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep (2010) 10(1):21–8. 10.1007/s11882-009-0078-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hawrylowicz CM, O’Garra A. Potential role of interleukin-10-secreting regulatory T cells in allergy and asthma. Nat Rev Immunol (2005) 5(4):271–83. 10.1038/nri1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakagome K, Imamura M, Kawahata K, Harada H, Okunishi K, Matsumoto T, et al. High expression of IL-22 suppresses antigen-induced immune responses and eosinophilic airway inflammation via an IL-10-associated mechanism. J Immunol (2011) 187(10):5077–89. 10.4049/jimmunol.1001560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michael H, Li Y, Wang Y, Xue D, Shan J, Mazer BD, et al. TGF-beta-mediated airway tolerance to allergens induced by peptide-based immunomodulatory mucosal vaccination. Mucosal Immunol (2015) 8(6):1248–61. 10.1038/mi.2015.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smaldini PL, Orsini Delgado ML, Fossati CA, Docena GH. Orally-induced intestinal CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ Treg controlled undesired responses towards oral antigens and effectively dampened food allergic reactions. PLoS One (2015) 10(10):e0141116. 10.1371/journal.pone.0141116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harris PR, Wright SW, Serrano C, Riera F, Duarte I, Torres J, et al. Helicobacter pylori gastritis in children is associated with a regulatory T-cell response. Gastroenterology (2008) 134(2):491–9. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sutton P, Robinson K. Do Helicobacter pylori therapeutic vaccines need to be tailored to the age of the recipient? Expert Rev Vaccines (2012) 11(4):415–7. 10.1586/erv.12.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Freire de Melo F, Rocha AM, Rocha GA, Pedroso SH, de Assis Batista S, Fonseca de Castro LP, et al. A regulatory instead of an IL-17 T response predominates in Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis in children. Microbes Infect (2012) 14(4):341–7. 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cook KW, Letley DP, Ingram RJ, Staples E, Skjoldmose H, Atherton JC, et al. CCL20/CCR6-mediated migration of regulatory T cells to the Helicobacter pylori-infected human gastric mucosa. Gut (2014) 63(10):1550–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robinson K, Bradley JE. The allergy epidemic: can helminths supply the antidote? Clin Exp Allergy (2010) 40(11):1586–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Y, Argent RH, Letley DP, Thomas RJ, Atherton JC. Tyrosine phosphorylation of CagA from Chinese Helicobacter pylori isolates in AGS gastric epithelial cells. J Clin Microbiol (2005) 43(2):786–90. 10.1128/JCM.43.2.786-790.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rhead JL, Letley DP, Mohammadi M, Hussein N, Mohagheghi MA, Eshagh Hosseini M, et al. A new Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin determinant, the intermediate region, is associated with gastric cancer. Gastroenterology (2007) 133(3):926–36. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Robinson K, Neal KR, Howard C, Stockton J, Atkinson K, Scarth E, et al. Characterization of humoral and cellular immune responses elicited by meningococcal carriage. Infect Immun (2002) 70(3):1301–9. 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1301-1309.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Battye F. (2015). Available from: http://www.frankbattye.com.au/Weasel/

- 74.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res (2001) 29(9):e45. 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wheeler DJ, Robins RA, Pritchard DI, Bundick RV, Shakib F. Peripheral blood based T cell-containing and T cell-depleted culture systems for human IgE synthesis: the role of T cells. Clin Exp Allergy (1996) 26(1):28–35. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1996.tb00053.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Meiler F, Klunker S, Zimmermann M, Akdis CA, Akdis M. Distinct regulation of IgE, IgG4 and IgA by T regulatory cells and toll-like receptors. Allergy (2008) 63(11):1455–63. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01774.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Akdis CA, Blesken T, Akdis M, Wuthrich B, Blaser K. Role of interleukin 10 in specific immunotherapy. J Clin Invest (1998) 102(1):98–106. 10.1172/JCI2250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tsang MLS, Weatherbee JA, Dietz M, Kitamura T, Lucas RC. TGF-beta specifically inhibits the IL-4 dependent proliferation of multifactor-dependent murine T-helper and human hematopoietic cell lines. Lymphokine Res (1990) 9:607–9. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baecher-Allan C, Brown JA, Freeman GJ, Hafler DA. CD4+CD25high regulatory cells in human peripheral blood. J Immunol (2001) 167(3):1245–53. 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Baecher-Allan C, Viglietta V, Hafler DA. Human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Semin Immunol (2004) 16(2):89–98. 10.1016/j.smim.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Heo YJ, Joo YB, Oh HJ, Park MK, Heo YM, Cho ML, et al. IL-10 suppresses Th17 cells and promotes regulatory T cells in the CD4+ T cell population of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Immunol Lett (2010) 127(2):150–6. 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ren Z, Pang G, Lee R, Batey R, Dunkley M, Borody T, et al. Circulating T-cell response to Helicobacter pylori infection in chronic gastritis. Helicobacter (2000) 5(3):135–41. 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Testi R, D’Ambrosio D, De Maria R, Santoni A. The CD69 receptor: a multipurpose cell-surface trigger for hematopoietic cells. Immunol Today (1994) 15(10):479–83. 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90193-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lundgren A, Suri-Payer E, Enarsson K, Svennerholm AM, Lundin BS. Helicobacter pylori-specific CD4+ CD25high regulatory T cells suppress memory T-cell responses to H. pylori in infected individuals. Infect Immun (2003) 71(4):1755–62. 10.1128/IAI.71.4.1755-1762.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Caron G, Duluc D, Fremaux I, Jeannin P, David C, Gascan H, et al. Direct stimulation of human T cells via TLR5 and TLR7/8: flagellin and R-848 up-regulate proliferation and IFN-gamma production by memory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol (2005) 175(3):1551–7. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Janson PC, Winerdal ME, Marits P, Thorn M, Ohlsson R, Winqvist O. FOXP3 promoter demethylation reveals the committed Treg population in humans. PLoS One (2008) 3(2):e1612. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lundin BS, Enarsson K, Kindlund B, Lundgren A, Johnsson E, Quiding-Jarbrink M, et al. The local and systemic T-cell response to Helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer patients is characterised by production of interleukin-10. Clin Immunol (2007) 125(2):205–13. 10.1016/j.clim.2007.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Windle HJ, Ang YS, Athie-Morales V, McManus R, Kelleher D. Human peripheral and gastric lymphocyte responses to Helicobacter pylori NapA and AphC differ in infected and uninfected individuals. Gut (2005) 54(1):25–32. 10.1136/gut.2003.025494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jakob B, Birkholz S, Schneider T, Duchmann R, Zeitz M, Stallmach A. Immune response to autologous and heterologous Helicobacter pylori antigens in humans. Microsc Res Tech (2001) 53(6):419–24. 10.1002/jemt.1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gagliani N, Magnani CF, Huber S, Gianolini ME, Pala M, Licona-Limon P, et al. Coexpression of CD49b and LAG-3 identifies human and mouse T regulatory type 1 cells. Nat Med (2013) 19(6):739–46. 10.1038/nm.3179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu Y, Carlsson R, Comabella M, Wang J, Kosicki M, Carrion B, et al. FoxA1 directs the lineage and immunosuppressive properties of a novel regulatory T cell population in EAE and MS. Nat Med (2014) 20(3):272–82. 10.1038/nm.3485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Watanabe T, Asano N, Fichtner-Feigl S, Gorelick PL, Tsuji Y, Matsumoto Y, et al. NOD1 contributes to mouse host defense against Helicobacter pylori via induction of type I IFN and activation of the ISGF3 signaling pathway. J Clin Invest (2010) 120(5):1645–62. 10.1172/JCI39481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Paradis TJ, Cole SH, Nelson RT, Gladue RP. Essential role of CCR6 in directing activated T cells to the skin during contact hypersensitivity. J Invest Dermatol (2008) 128(3):628–33. 10.1038/sj.jid.5701055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chung SH, Chang SY, Lee HJ, Choi SH. The C-C chemokine receptor 6 (CCR6) is crucial for Th2-driven allergic conjunctivitis. Clin Immunol (2015) 161(2):110–9. 10.1016/j.clim.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kayhan B, Arasli M, Eren H, Aydemir S, Aktas E, Tekin I. Analysis of peripheral blood lymphocyte phenotypes and Th1/Th2 cytokines profile in the systemic immune responses of Helicobacter pylori infected individuals. Microbiol Immunol (2008) 52(11):531–8. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2008.00066.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Oderda G, Vivenza D, Rapa A, Boldorini R, Bonsignori I, Bona G. Increased interleukin-10 in Helicobacter pylori infection could be involved in the mechanism protecting from allergy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr (2007) 45(3):301–5. 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3180ca8960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cam S, Ertem D, Bahceciler N, Akkoc T, Barlan I, Pehlivanoglu E. The interaction between Helicobacter pylori and atopy: does inverse association really exist? Helicobacter (2009) 14(1):1–8. 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00660.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee JH, Yu HH, Wang LC, Yang YH, Lin YT, Chiang BL. The levels of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in paediatric patients with allergic rhinitis and bronchial asthma. Clin Exp Immunol (2007) 148(1):53–63. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03329.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Codolo G, Mazzi P, Amedei A, Del Prete G, Berton G, D’Elios MM, et al. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori down-modulates Th2 inflammation in ovalbumin-induced allergic asthma. Cell Microbiol (2008) 10(11):2355–63. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01217.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.D’Elios MM, Codolo G, Amedei A, Mazzi P, Berton G, Zanotti G, et al. Helicobacter pylori, asthma and allergy. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol (2009) 56(1):1–8. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00537.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Memon AA, Hussein NR, Miendje Deyi VY, Burette A, Atherton JC. Vacuolating cytotoxin genotypes are strong markers of gastric cancer and duodenal ulcer-associated Helicobacter pylori strains: a matched case-control study. J Clin Microbiol (2014) 52(8):2984–9. 10.1128/JCM.00551-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kido M, Tanaka J, Aoki N, Iwamoto S, Nishiura H, Chiba T, et al. Helicobacter pylori promotes the production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin by gastric epithelial cells and induces dendritic cell-mediated inflammatory Th2 responses. Infect Immun (2010) 78(1):108–14. 10.1128/IAI.00762-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zeng M, Mao XH, Li JX, Tong WD, Wang B, Zhang YJ, et al. Efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of an oral recombinant Helicobacter pylori vaccine in children in China: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet (2015) 386(10002):1457–64. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60310-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sutton P. At last, vaccine-induced protection against Helicobacter pylori. Lancet (2015) 386(10002):1424–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60579-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]