Abstract

Many HIV-infected individuals do not enter health care until late in the infection course. Despite encouraging earlier testing, this situation has continued for several years. We investigated the prevalence of late presenters and factors associated with late presentation among HIV-infected patients in an Asian regional cohort. This cohort study included HIV-infected patients with their first positive HIV test during 2003–2012 and CD4 count and clinical status data within 3 months of that test. Factors associated with late presentation into care (CD4 count <200 cells/μl or an AIDS-defining event within ±3 months of first positive HIV test) were analyzed in a random effects logistic regression model. Among 3,744 patients, 2,681 (72%) were late presenters. In the multivariable model, older patients were more likely to be late presenters than younger (≤30 years) patients [31–40, 41–50, and ≥51 years: odds ratio (OR) = 1.57, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.31–1.88; OR = 2.01, 95% CI 1.58–2.56; and OR = 1.69, 95% CI 1.23–2.31, respectively; all p ≤ 0.001]. Injecting drug users (IDU) were more likely (OR = 2.15, 95% CI 1.42–3.27, p < 0.001) and those with homosexual HIV exposure were less likely (OR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.35–0.58, p < 0.001) to be late presenters compared to those with heterosexual HIV exposure. Females were less likely to be late presenters (OR = 0.44, 95% CI 0.36–0.53, p < 0.001). The year of first positive HIV test was not associated with late presentation. Efforts to reduce the patients who first seek HIV care at the late stage are needed. The identified risk factors associated with late presentation should be utilized in formulating targeted public health intervention to improve earlier entry into HIV care.

Introduction

In many countries, a substantial number of HIV-infected individuals still do not enter health care until late in their infection course. Despite attempts to encourage earlier HIV testing, this situation has persisted for several years, without evidence of improvement.1,2 A progressive loss of CD4 cells occurs during the natural course of HIV infection; the rate of this loss is variable, with an average of approximately 60–100 cells/μl per year.3–5 This loss of CD4 cells leads to a severely immunocompromised state in the infected host. Advanced HIV disease is characterized by a reduction in the CD4 cell count to <200 cells/μl, the presence of multiple comorbid opportunistic infections, and poor overall functional and mental health status.6,7 Late presenters into care have an increased risk of clinical progression and mortality, and exhibit slow or poor immune recovery after initiating combined antiretroviral-therapy (ART) and a higher frequency of antiretroviral-associated toxicity.8–10 Importantly, the numbers of patients unaware of their HIV status and remaining untreated have been shown to correlate with community viral load and therefore with the risk of HIV transmission.11 Late presentation for care is consequently harmful to both the infected person and the community's HIV response. Surveillance to identify the prevalence of and risk factors for late presentation into care is crucial, yet remains inadequate across Asia.12,13

The Therapeutics Research, Education, and AIDS Training in Asia (TREAT Asia) HIV Observational Database (TAHOD) is a multicenter, observational cohort study that was initiated in 2003 to assess regional HIV treatment outcomes in the Asia-Pacific region.14 In this study, we aimed to describe trends in late presentation into care and to determine associated factors in TAHOD.

Materials and Methods

Study population

We analyzed data from TAHOD, a prospective, observational cohort study of HIV-infected adults at 22 sites in the Asia-Pacific region that was established in 2003 (see Supplementary data: List of TAHOD Sites; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/aid).14 The database structure and standardized data collection and quality control mechanisms have been previously described.14 Briefly, each site recruits approximately 200–300 HIV-infected patients, both treated and untreated with ART. Recruitment was based on a consecutive series of patients who regularly attend a given site from a particular start-up time. Ethics approvals were obtained through institutional review boards for UNSW Australia (the University of New South Wales) the coordinating center at TREAT Asia, and each participating TAHOD site.

We enrolled only patients for whom CD4 cell counts and clinical status records within 3 months of the first positive HIV test date were available. Patients were included if their first positive HIV test was recorded in the database between 2003 and March 2012. To minimize selection bias, we excluded patients who were HIV-positive before TAHOD began actively enrolling patients in 2003.

Variables and definitions

The following data were included in the analyses: age at first positive HIV test, sex, year of first positive HIV test, CD4 cell count (cells/μl), HIV viral load (copies/ml), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stage at presentation, reported HIV infection route, and hepatitis serologies.

The exposure of interest was defined as the year of the first HIV-positive test. The primary endpoint was late presentation at the time of entering into care. Late presentation was defined as a CD4 cell count <200 cells/μl or an AIDS-defining event (CDC Category C) within 3 months of the first positive test.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the factors associated with late presentation, we performed logistic regression analyses with random effect on site, to adjust for potential clustering within each site. We performed a sensitivity analysis to determine the site-level effect on late presentation by including the World Bank income categories in the fixed-effect logistic model.15 Significant factors (p < 0.10) in the univariate model were included in the multivariate model. Using a backward stepwise selection process, factors significant at p < 0.05 were adjusted for in the final multivariate model. Descriptive statistics for the categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared or Fisher's exact test, and continuous variables were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA (version 12.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 5,415 patients in TAHOD were recorded as having their first positive HIV test between 2003 and 2012. To analyze late presentation into care, 3,744 patients were included in the study; patients with no AIDS diagnosis and no CD4 measurements available within ±3 months of their first positive HIV test were excluded.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of patients with early or late presentation at first positive HIV test. Of the 3,744 patients, 2,681 (72%) were late presenters. Approximately 72% were male, 38% were aged 31–40 years, and 64% were exposed to HIV via heterosexual contact.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at First Positive HIV Test

| Total | Early presentation | Late presentation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 3744 (100%) | n = 1063 (28%) | n = 2681 (72%) | p-valuea | |

| Year of first positive test, n (%) | ||||

| 2003–2006 | 1395 (37) | 489/1395 (35) | 906/1395 (65) | <0.001 |

| 2007–2009 | 1476 (39) | 348/1476 (24) | 1128/1476 (76) | |

| 2010–2012 | 873 (23) | 226/873 (26) | 647/873 (74) | |

| Age, median years (IQR) | 34 (28–41) | 32 (26–39) | 35 (29–42) | <0.001 |

| Age, years, n (%) | ||||

| ≤30 | 1320 (35) | 485/1320 (37) | 835/1320 (63) | <0.001 |

| 31–40 | 1436 (38) | 361/1436 (25) | 1075/1436 (75) | |

| 41–50 | 675 (18) | 141/675 (21) | 534/675 (79) | |

| ≥51 | 313 (8) | 76/313 (24) | 237/313 (76) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 2691 (72) | 707/2691 (26) | 1984/2691 (74) | <0.001 |

| Female | 1053 (28) | 356/1053 (34) | 697/1053 (66) | |

| HIV exposure category, n (%) | ||||

| Heterosexual contact | 2394 (64) | 612/2394 (26) | 1782/2394 (74) | <0.001 |

| Homosexual contact | 684 (18) | 306/684 (45) | 378/684 (55) | |

| Injecting drug use | 343 (9) | 32/343 (9) | 311/343 (91) | |

| Otherb | 323 (9) | 113/323 (35) | 210/323 (65) | |

| Hepatitis B coinfection, n (%) | ||||

| Negative | 2650 (71) | 708/2650 (27) | 1942/2650 (73) | 0.606 |

| Positive | 327 (9) | 83/327 (25) | 244/327 (75) | |

| Not tested | 767 (20) | 272/767 (35) | 495/767 (65) | |

| Hepatitis C coinfection, n (%) | ||||

| Negative | 2306 (62) | 642/2306 (28) | 1664/2306 (72) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 456 (12) | 68/456 (15) | 388/456 (85) | |

| Not tested | 982 (26) | 353/982 (36) | 629/982 (64) | |

Excluding not tested or missing values.

Includes those exposed to blood products and unknown exposures.

Late presentation was defined as a CD4 cell count <200 cells/μl or an AIDS-defining event (CDC Category C) within 3 months of the first positive test.

IQR, interquartile range

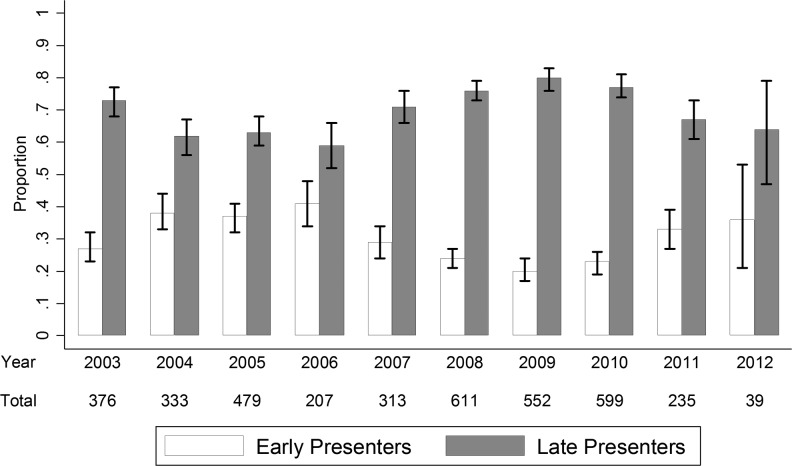

Table 2 lists the factors associated with late presentation after adjusting for site clustering. The year of the first positive test, as illustrated in Fig. 1, was not associated with late presentation. The following factors were independently associated with late presentation into care according to the multivariate regression analysis: older age [31–40 years: odds ratio (OR) = 1.57, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.31–1.88; 41–50 years: OR = 2.01, 95% CI 1.58–2.56; and ≥51 years: OR = 1.69, 95% CI 1.23–2.31 compared to the age less than 30 years old, all p ≤ 0.001] and the injecting drug user (IDU) HIV exposure category (OR = 2.15 versus heterosexual contact, 95% CI: 1.42–3.27; p < 0.001). In contrast, homosexual HIV exposure had an odds reduction of 55% for late presentation (OR = 0.45, 95% CI: 0.35–0.58; p < 0.001). Female sex was also found to be a protective factor (OR = 0.44 versus the male sex, 95% CI: 0.36–0.53; p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Late Presentation at First Positive HIV Test

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients No. | Late presenters (%) | OR | 95% CI | p-value | Global p-valuea | OR | 95% CI | p-value | Global p-valuea | |

| Year of first positive test | ||||||||||

| 2003–2006 | 1395 | 906 (65) | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 2007–2009 | 1476 | 1128 (76) | 1.00 | (0.82–1.24) | 0.969 | 1.10 | (0.89–1.37) | 0.381 | ||

| 2010–2012 | 873 | 647 (74) | 1.13 | (0.88–1.46) | 0.348 | 0.591 | 1.21 | (0.93–1.58) | 0.150 | 0.344 |

| Age, years | ||||||||||

| ≤30 | 1320 | 835 (63) | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| 31–40 | 1436 | 1075 (75) | 1.74 | (1.46–2.07) | <0.001 | 1.57 | (1.31–1.88) | <0.001 | ||

| 41–50 | 675 | 534 (79) | 2.28 | (1.80–2.89) | <0.001 | 2.01 | (1.58–2.56) | <0.001 | ||

| ≥51 | 313 | 237 (76) | 2.03 | (1.49–2.76) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.69 | (1.23–2.31) | 0.001 | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 2691 | 1984 (74) | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Female | 1053 | 697 (66) | 0.44 | (0.37–0.53) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.44 | (0.36–0.53) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| HIV exposure category | ||||||||||

| Heterosexual contact | 2394 | 1782 (74) | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Homosexual contact | 684 | 378 (55) | 0.54 | (0.42–0.68) | <0.001 | 0.45 | (0.35–0.58) | <0.001 | ||

| Injecting drug use | 343 | 311 (91) | 2.88 | (1.92–4.31) | <0.001 | 2.15 | (1.42–3.27) | <0.001 | ||

| Otherb | 323 | 210 (65) | 0.82 | (0.62–1.08) | 0.163 | <0.001 | 0.76 | (0.57–1.02) | 0.068 | <0.001 |

| Hepatitis B coinfection | ||||||||||

| Negative | 2650 | 1942 (73) | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Positive | 327 | 244 (75) | 1.02 | (0.77–1.35) | 0.887 | 0.94 | (0.71–1.26) | 0.700 | ||

| Not tested | 767 | 495 (65) | 0.83 | (0.67–1.03) | 0.092 | 0.887 | 0.84 | (0.67–1.05) | 0.116 | 0.700 |

| Hepatitis C coinfection | ||||||||||

| Negative | 2306 | 1664 (72) | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Positive | 456 | 388 (85) | 1.84 | (1.36–2.49) | <0.001 | 1.11 | (0.71–1.56) | 0.556 | ||

| Not tested | 982 | 629 (64) | 0.73 | (0.60–0.90) | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.72 | (0.59–0.89) | 0.002 | 0.556 |

Global p-values indicate tests for heterogeneity, excluding untested or missing values.

Includes those exposed to blood products and unknown exposures.

p-values in bold represent significant covariates in the final model. Nonsignificant factors are presented in the significant predictor adjusted multivariate model. Late presentation was defined as a CD4 cell count <200 cells/μl or an AIDS-defining event (CDC Category C) within 3 months of the first positive test.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

FIG. 1.

Proportion of late presenters at first positive test.

We included the country income level variable in the sensitivity analysis as a fixed covariate to determine whether there was a site-level association with late presentation. There was one site categorized as “low” income, seven sites as “lower-middle,” nine sites as “upper-middle,” and six sites as “high.” The categories were combined further into “low + lower-middle income” and “upper-middle + high income.” After adjusting for country income in the univariate model, we found no association between “upper middle + high income” countries compared with “low + lower-middle income” countries in the association with late presentation (OR = 1.07, 95% CI 0.93–1.23; p = 0.375).

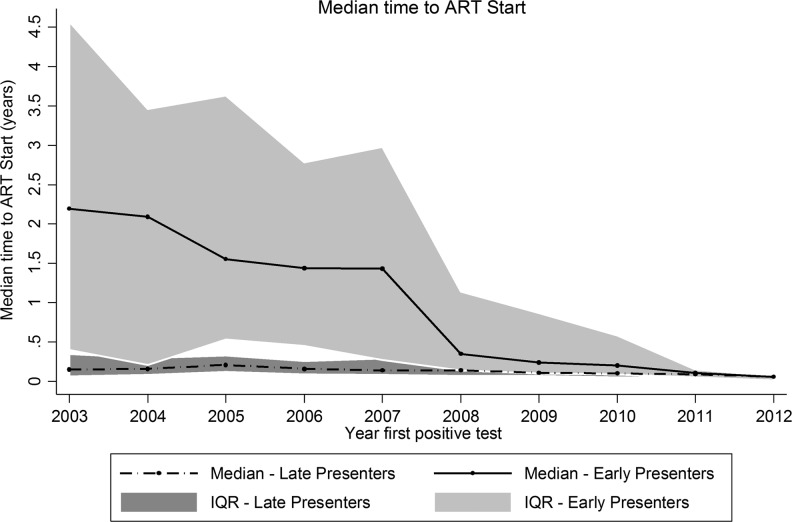

Figure 2 presents a graph of the median time to ART initiation according to the year in which the first positive HIV test was obtained. A total of 3,429 patients who had begun receiving ART were included. Patients who satisfied the definition of late presentation began receiving ART relatively soon after the first HIV-positive test. Previously, the median time to treatment initiation among early presenters was much longer, as those who presented early in 2003 had a median time to treatment of 2.19 years (interquartile range 0.40–4.57) vs. a median of 0.35 years (interquartile range 0.14–1.14, p < 0.001) for those who presented in 2008, the time period in which the sharpest decline was observed. When the early and late presenters were compared, the early presenters in 2003 had a significantly longer time to ART initiation (2.19 years vs. 0.15 years, p < 0.001); this difference remained significant in 2008 (0.35 years vs. 0.14 years, p < 0.001). Beginning in 2011, the time to ART initiation was similar in both groups (2011: 0.11 years vs. 0.09 years; p = 0.233, and 2012: 0.06 years vs. 0.06 years; p = 0.364). It is important to note that only 25 patients were included in 2012 because of our analysis cut-off date of March 2012.

FIG. 2.

The median time to antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation in HIV-infected patients. Late presenter was defined as an HIV-infected patient with CD4 cell count <200 cells/μl or an AIDS-defining event (CDC Category C) within 3 months of the first positive test.

Discussion

ART has significantly changed the natural history of HIV infection and has led to great reductions in morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected patients.16 However, more than one-third of patients with HIV infection in Europe receive late diagnoses17 and in the North America AIDS Cohort Collaboration (NA-ACCORD), the CD4 counts at first presentation have increased since 1997, although the proportion of patients who presented with CD4 counts <350 cells/μl remained 54% in 2007.18 In the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) global consortium, the baseline CD4 counts across four regions in sub-Saharan Africa ranged from 126 to 211 cells/μl among patients presenting for care.19 Therefore, the prevalence of late presentation to care did not decrease worldwide over time even after the introduction of ART.

To our knowledge, this is the first regional report from the Asia-Pacific to examine the prevalence and risk factors of late presentation to care. In this study, we found that 72% of the patients presented late. It is difficult to compare the prevalence rates in earlier studies because a standardized definition of late presentation was not yet applied. After allowing for different definitions, the present study reported a greater proportion of HIV patients with late presentation than most of the other studies. Even after the introduction of ART, 55% of newly diagnosed patients were symptomatic at baseline ranging from a low of 39% in the first half of 1994 to a high of 71% in the second half of 1998 at a clinic in the United States.20 In a province of Thailand, 55% of the patients who received initial HIV diagnoses from 2004 to 2005 presented with HIV-related symptoms at diagnosis.21 Several studies reported that the late presentation for care observed in developing regions such as sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America was due to limited health care access and health literacy.22,23

The median time to starting ART after a new HIV diagnosis has been reduced and, in more recent years, a trend toward early ART initiation after HIV diagnosis has been observed among both early and late presenters, notably after the changes in the CD4 thresholds for ART initiation in international guidelines.24 However, despite having a mix of low- to high-income countries, patients in this cohort continue to have a high rate of late presentation into care, which presents a barrier to early ART. Early HIV diagnosis and retention in HIV care represent an important opportunity for achieving earlier access to treatment and reducing the risk of transmission.25 Late presentation into care and consequent delays in ART initiation are associated with more HIV-related, opportunistic infections, increased morbidity and mortality, diminished responses to ART, and health care expenditures.9,26,27 Therefore, the reduction of late presentation into care should be a top HIV care priority in this region.

In the multivariate analysis, older age, male sex, and IDU were significant risk factors for late presentation into care. This finding suggests a lower risk perception in these populations and implies an insufficient level of HIV testing. Older age (≥30 years) was associated with increased risk of late presentation, and this result corresponds to the findings of previous studies.28,29 Late-diagnosed patients would be expected to be older than patients diagnosed for other reasons because HIV-related symptoms usually develop after a prolonged period of infection at which point the immune system has been weakened.30,31 In addition, a previous study reported that older patients were more likely to be diagnosed during hospitalization, and they suggested that these populations may have a lower perceived risk for HIV infection.32

Late presentation was more common among men and was associated with IDU and heterosexual HIV exposure. These findings are consistent with those of other studies. Previous studies have reported the proportion of late diagnosis to be lower among men who have sex with men.28,33 In addition, several previous reports identified IDU as a high-risk population for late diagnosis and care.34,35 Females seem less likely to present late and this could be due to HIV testing during pregnancy. Furthermore, females get tested soon after their spouse test HIV positive, thereby discovering the virus at a much earlier stage of infection that their partners.

There are several limitations to this study. TAHOD data were collected from urban referral centers, which are more likely to receive referrals of sicker patients with advanced immune deficiency. Therefore, TAHOD participants are not necessarily representative of all HIV-infected patients in Asian countries, and therefore our results might not be fully generalizable. We could not analyze the impact of socioeconomic factors on late presentation as those data were not available. In addition, retrospective patient information collection in resource-limited settings remains a challenge.

In the past decade, 72% of the HIV patients in TAHOD who entered care were late presenters. Patients who present late to HIV care are often ill, have a high early mortality risk, are less likely to respond to ART, and have an increased forward HIV transmission risk. In order to achieve earlier entry into care, HIV testing programs, including provision of medical support involving HIV testing services for elderly populations with poor access to health care or regular check-up in IDU, must ensure the inclusion of those at highest risk of having HIV and of those missed by traditional HIV outreach programs. Region-specific efforts to facilitate early diagnosis should be implemented.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The study team would like to acknowledge TAHOD-TASER study members, steering committee, and patients for their support.

TAHOD-TASER study members:

• A Kamarulzaman, SF Syed Omar, S Ponnampalavanar, I Azwa, N Huda, and LY Ong, University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia;

• BLH Sim, YM Gani, and R David, Hospital Sungai Buloh, Sungai Buloh, Malaysia;

• CV Mean, V Saphonn, and V Khol, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology and STDs, Phnom Penh, Cambodia;

• E Yunihastuti,† D Imran, and A Widhani, Working Group on AIDS Faculty of Medicine, University of Indonesia/Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia;

• FJ Zhang, HX Zhao, and N Han, Beijing Ditan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China;

• JY Choi, Na S, and JM Kim, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea;

• M Mustafa, and N Nordin, Hospital Raja Perempuan Zainab II, Kota Bharu, Malaysia;

• N Kumarasamy, S Saghayam, and C Ezhilarasi, YRGCARE Medical Centre, VHS, Chennai, India;

• OT Ng, PL Lim, LS Lee, and PS Ohnmar, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore;

• MP Lee, PCK Li, W Lam, and YT Chan, Queen Elizabeth Hospital and KH Wong, Integrated Treatment Centre, Hong Kong, China;

• P Kantipong and P Kambua, Chiangrai Prachanukroh Hospital, Chiang Rai, Thailand;

• P Phanuphak, K Ruxrungtham, A Avihingsanon, P Chusut, and S Sirivichayakul, HIV-NAT/Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre, Bangkok, Thailand;

• R Ditangco,† E Uy, and R Bantique, Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, Manila, Philippines;

• R Kantor, Brown University, Rhode Island, United States;

• S Oka, J Tanuma, and T Nishijima, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan;

• S Pujari, K Joshi, and A Makane, Institute of Infectious Diseases, Pune, India;

• S Kiertiburanakul, S Sungkanuparph, L Chumla, and N Sanmeema, Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand;

• TP Merati,‡ DN Wirawan, and F Yuliana, Faculty of Medicine, Udayana University and Sanglah Hospital, Bali, Indonesia;

• R Chaiwarith, T Sirisanthana, W Kotarathititum, and J Praparattanapan, Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand;

• TT Pham, DD Cuong, and HL Ha, Bach Mai Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam;

• VK Nguyen, VH Bui, and TT Cao, National Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Hanoi, Vietnam;

• W Ratanasuwan and R Sriondee, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand;

• WW Wong, WW Ku, and PC Wu, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan;

• YMA Chen and YT Lin, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung City, Taiwan;

• AH Sohn, N Durier, B Petersen, and T Singtoroj, TREAT Asia, amfAR—The Foundation for AIDS Research, Bangkok, Thailand;

• DA Cooper, MG Law, A Jiamsakul, and DC Boettiger, The Kirby Institute, UNSW Australia, Sydney, Australia.

The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database, TREAT Asia Studies to Evaluate Resistance, and the Australian HIV Observational Database are initiatives of TREAT Asia, a program of amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, with support from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs through a partnership with Stichting Aids Fonds, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and National Cancer Institute, as part of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA; U01AI069907). Queen Elizabeth Hospital and the Integrated Treatment Centre received additional support from the Hong Kong Council for AIDS Trust Fund. The Kirby Institute is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, UNSW Australia (The University of New South Wales). J.Y.C.'s involvement was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2013R1A1A2005412), a grant from Chronic Infectious Disease Cohort (4800-4859-304-260) from Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and BioNano Health-Guard Research Center funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (MSIP) of Korea as Global Frontier Project (H-GUARD_2013M3A6B2078953). The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the governments or institutions mentioned above.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Current Steering Committee Chairs;

co-Chairs.

References

- 1.Fisher M: Late diagnosis of HIV infection: Major consequences and missed opportunities. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2008;21(1):1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler A, Mounier Jack S, and Coker RJ: Late diagnosis of HIV in Europe: Definitional and public health challenges. AIDS Care 2009;21(3):284–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirschner D, Webb GF, and Cloyd M: Model of HIV-1 disease progression based on virus-induced lymph node homing and homing-induced apoptosis of CD4+ lymphocytes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2000;24(4):352–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang W, Perkins H, Anderson RE, et al. : Patterns of T lymphocyte changes with human immunodeficiency virus infection: From seroconversion to the development of AIDS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1989;2(1):63–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samet JH, Freedberg KA, Savetsky JB, et al. : Understanding delay to medical care for HIV infection: The long-term non-presenter. AIDS 2001;15(1):77–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manga NM, Diop SA, Ndour CT, et al. : [Late diagnosis of HIV infection in the Fann, Dakar clinic of infectious diseases: Testing circumstances, therapeutic course of patients, and determining factors]. Med Mal Infect 2009;39(2):95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Säll L, Salamon E, Allgulander C, and Owe Larsson B: Psychiatric symptoms and disorders in HIV infected mine workers in South Africa. A retrospective descriptive study of acute first admissions. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg) 2009;12(3):206–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelley CF, Kitchen CM, Hunt PW, et al. : Incomplete peripheral CD4+ cell count restoration in HIV-infected patients receiving long-term antiretroviral treatment. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48(6):787–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egger M, May M, Chêne G, et al. : Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: A collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet (London, England) 2002;360(9327):119–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin H, et al. : The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009;23(1):41–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks G, Crepaz N, and Janssen RS: Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS 2006;20(10):1447–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choe PG, Park WB, Song JS, et al. : Late presentation of HIV disease and its associated factors among newly diagnosed patients before and after abolition of a government policy of mass mandatory screening. J Infect 2011;63(1):60–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mojumdar K, Vajpayee M, Chauhan NK, and Mendiratta S: Late presenters to HIV care and treatment, identification of associated risk factors in HIV-1 infected Indian population. BMC Public Health 2010;10(1):416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J, Kumarasamy N, Ditangco R, et al. : The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database: Baseline and retrospective data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005;38(2):174–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The World Bank available at http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups, 2014

- 16.Berretta M, Cinelli R, Martellotta F, et al. : Therapeutic approaches to AIDS-related malignancies. Oncogene 2003;22(42):6646–6659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mocroft A, Lundgren JD, Sabin ML, et al. : Risk factors and outcomes for late presentation for HIV-positive persons in Europe: Results from the Collaboration of Observational HIV Epidemiological Research Europe Study (COHERE). PLoS Med 2013;10(9):e1001510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Althoff KN, Gange SJ, Klein MB, et al. : Late presentation for human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50(11):1512–1520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egger M, Ekouevi DK, Williams C, et al. : Cohort Profile: The international epidemiological databases to evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41(5):1256–1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sackoff JE. and Shin SS: Trends in immunologic and clinical status of newly diagnosed HIV-positive patients initiating care in the HAART era. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2001;28(3):270–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thanawuth N. and Chongsuvivatwong V: Late HIV diagnosis and delay in CD4 count measurement among HIV-infected patients in Southern Thailand. AIDS Care 2008;20(1):43–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sepkowitz KA: One disease, two epidemics—AIDS at 25. N Engl J Med 2006;354(23):2411–2414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuboi SH, Brinkhof MW, Egger M, et al. : Discordant responses to potent antiretroviral treatment in previously naive HIV-1-infected adults initiating treatment in resource-constrained countries: The antiretroviral therapy in low-income countries (ART-LINC) collaboration. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;45(1):52–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DHHS: Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1 Intected Adults and Adolescents available at https://aidsinfo.nih.gov, 2008

- 25.Phillips AN, Gazzard B, Gilson R, et al. : Rate of AIDS diseases or death in HIV-infected antiretroviral therapy-naive individuals with high CD4 cell count. AIDS 2007;21(13):1717–1721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen RY, Accortt NA, Westfall AO, et al. : Distribution of health care expenditures for HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42(7):1003–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiertiburanakul S, Boettiger D, Lee MP, et al. : Trends of CD4 cell count levels at the initiation of antiretroviral therapy over time and factors associated with late initiation of antiretroviral therapy among Asian HIV-positive patients. J Int AIDS Soc 2014;17(1):18804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Camoni L, Raimondo M, Regine V, et al. : Late presenters among persons with a new HIV diagnosis in Italy, 2010–2011. BMC Public Health 2013;13(1):281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith RD, Delpech VC, Brown AE, and Rice BD: HIV transmission and high rates of late diagnoses among adults aged 50 years and over. AIDS 2010;24(13):2109–2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borghi V, Girardi E, Bellelli S, et al. : Late presenters in an HIV surveillance system in Italy during the period 1992–2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;49(3):282–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilbart V, Dougan S, Sinka K, and Evans B: Late diagnosis of HIV infection among individuals with low, unrecognised or unacknowledged risks in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. AIDS Care 2006;18(2):133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mugavero MJ, Castellano C, Edelman D, and Hicks C: Late diagnosis of HIV infection: The role of age and sex. Am J Med 2007;120(4):370–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gott CM: Sexual activity and risk-taking in later life. Health Soc Care Community 2001;9(2):72–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Girardi E, Aloisi MS, Arici C, et al. : Delayed presentation and late testing for HIV: Demographic and behavioral risk factors in a multicenter study in Italy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;36(4):951–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Celentano DD, Galai N, Sethi AK, et al. : Time to initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected injection drug users. AIDS 2001;15(13):1707–1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.