Abstract

The objective of this study was to compare outcomes in patients with rotator cuff tears undergoing all-arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair. A systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes of all-arthroscopic repair versus mini-open repair in patients with rotator cuff repair was conducted. Studies meeting the inclusion criteria were screened and included from systematic literature search for electronic databases including Medline, Embase, Cochrane CENTRAL, and CINAHL library was conducted from 1969 and 2015. A total of 18 comparative studies including 4 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) were included. Pooled results indicate that there was no difference in the functional outcomes, range of motion, visual analog scale (VAS) score, and short-form 36 (SF-36) subscales. However, Constant-Murley functional score was found to be significantly better in patients with mini-open repair. However, the results of the review should be interpreted with caution due to small size and small number of studies contributing to analysis in some of the outcomes. All-arthroscopic and mini-open repair surgical techniques for the management of rotator cuff repair are associated with similar outcomes and can be used interchangeably based on the patient and rotator tear characteristics.

Rotator cuff tears are common amongst the elderly and athletes. Surgery is usually required to help regain the muscle strength, function and flexibility of the shoulder, and to relieve the pain. There are many ways of repairing the rotator cuff tears, including arthroscopy, open surgery, or a combination of both. Clinical guidelines recommend using open surgery, mini-open surgery or arthroscopy for a full-thickness tear accessible to direct repair by suture1. Surgery has been found to be associated with better results compared to non-surgery2. Although, mini-open rotator cuff repair and arthroscopic repair are commonly performed for the treatment of rotator cuff tears, with comparable results; however, there is uncertainty on the long term outcomes using the two techniques3.

Methods

Study design

A systematic review was conducted in adult patients with rotator cuff tears other than massive or irreparable tears to compare clinical outcomes of patients undergoing all-arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair. The review was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

Data sources

A systematic literature search of electronic databases for relevant studies between 1963 to May 2015 was conducted through Embase®, MEDLINE®, Cochrane CENTRAL, and CINAHL. Studies published in English language were identified using search terms like ‘rotator cuff’, ‘arthroscopy’, ‘mini-open’, and ‘supraspinatus’.

Study eligibility

Studies were screened based on the predefined inclusion criteria. Comparative studies reporting all-arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR) (no concurrent acromioplasty, superior labrum anterior to posterior [SLAP] or other procedures) versus mini-open RCR (no concurrent procedures) were included. Additionally, studies reporting sub-group data for patients of interest to the review were also included. Relevant outcomes of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR) or mini-open rotator cuff repair (MRCR) included functional scores (University of California Los Angeles [UCLA] shoulder score, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [ASES] shoulder outcome score, Constant-Murley scores), range of motion (abduction, forward flexion, external rotation); pain visual analog scale (VAS) score, and complications (retear, adhesive capsulitis). No restriction was employed to study design, with both retrospective and prospective cohort studies were included, except for case studies.

Data collection

Bibliographic details and abstracts of all citations were retrieved through database searches. A team of independent reviewers specialized in evidence-based medicine determined the eligibility of each publication. Citations were initially screened on the basis of title/abstract supplied with each citation by applying the defined set of eligibility criteria described above. Duplicates of citations (due to overlap in the coverage of the databases) were excluded at this stage. Full text copies were ordered for studies that potentially met the eligibility criteria. The eligibility criteria were then applied to the full-text publications, with each publication being reviewed by an independent two review process.

Data was extracted from the full-text articles of included studies using a specifically designed data extraction grid. Only one dataset per study was compiled from all publications related to that study in order to avoid duplication of data. Outcome data from eligible studies were extracted from the latest time point in all trials.

Study quality

Study quality was assessed using Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort studies and Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias for randomized controlled trials.

Statistical analysis

Results will be expressed as mean differences for continuous outcomes (standardized vs. weighted to be determined by available data); and the appropriate ratio/difference for dichotomous outcomes as determined by available data. For pooled analyses and forest plot generation, we used Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software. To test the robustness of our results, we will perform sensitivity analyses to be determined by the available data. Random effects models will be used, as will appropriate tests for heterogeneity.

Results

Identification of relevant studies

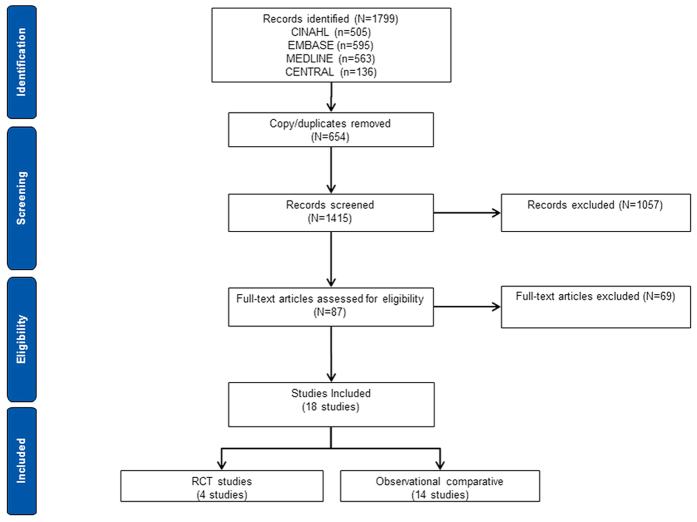

Literature search yielded 1799 studies, of which 87 potentially relevant full-text articles were identified for detailed evaluation. Following detailed screening, 18 studies evaluating arthroscopy and mini-open repair for rotator-cuff repair were included in the review (Fig. 1). The included evidence was based on comparative studies assessing clinical outcomes or providing sub-group data on outcomes of interest in patients with rotator-cuff tear.

Figure 1. Trial flow of included studies.

The list of studies included in the review along with study characteristics is presented in Table 1. Of the 18 included studies, 7 studies were conducted in the USA, three in South Korea, two in Germany, and one each in UK, Turkey, France, Italy, China, and the Netherlands. Of the included studies, four were RCT and 14 were observational studies over a data collection period from 2000 to 2014.

Table 1. Details of included studies.

| Study | Year | Study type | Group | Country | Sample size | F/M | Mean age | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cho et al. | 2012 | RCT | ASR | South Korea | 30 | 13/17 | 55.5y | 6m |

| MOR | 30 | 13/17 | 56.2y | 6m | ||||

| Chung et al. | 2013 | Prospective | ASR | South Korea | 225 | 160/128 | 59.5y | 22.8m |

| MOR | 41 | |||||||

| OP | 22 | |||||||

| Colegate-Stone et al. | 2009 | Retrospective | ASR | United Kingdom | 92 | 48/44 | 57y | 24m |

| MOR | 31 | 15/16 | 62y | 24m | ||||

| Kang et al. | 2007 | Retrospective | ASR | USA | 65 | NG | NG | 6m |

| MOP | 63 | 6m | ||||||

| Kasten et al. | 2011 | RCT | ASR | Germany | 17 | 8/9 | 60.1y | 6m |

| MOR | 17 | 5/12 | 60.1y | 6m | ||||

| Kim et al. | 2003 | Retrospective | ASR | South Korea | 42 | 15/27 | 55y | 39m(24–72) |

| MOR | 34 | 22/12 | 55y | 39m(24–72) | ||||

| Kose et al. | 2008 | Retrospective | ASR | Turkey | 25 | 18/7 | 55y | 31.20m |

| MOR | 25 | 21/4 | 62y | 21.56m | ||||

| Liem et al. | 2007 | Retrospective | ASR | Germany | 19 | 3/16 | 61.9y | 25.0m |

| MOR | 19 | 3/16 | 62.1y | 17.6m | ||||

| Nové-Josserand et al. | 2011 | Retrospective | ASR | France | 154 | 71/183 | 50.5y | NG |

| MOR | ||||||||

| Osti et al. | 2010 | Retrospective | ASR | Italy | 32 | 17/15 | 56.1y | 30.6m |

| MOR | 32 | 14/18 | 56y | 31m | ||||

| Pearsall et al. | 2007 | Prospective | ASR | USA | 25 | 14/11 | 58y | 50.6m |

| MOR | 27 | 17/10 | 55y | 50.6m | ||||

| Sauerbrey et al. | 2005 | Retrospective | ASR | USA | 26 | 10/16 | 56y | 19m |

| MOR | 28 | 12/16 | 57y | 33m | ||||

| Severud et al. | 2003 | Retrospective | ASR | USA | 35 | NG | NG | 44.6m |

| MOR | 29 | 44.6m | ||||||

| Verma et al. | 2006 | Retrospective | ASR | USA | 38 | 16/22 | 59.4y | 24m |

| MOR | 33 | 10/23 | 60.7y | 24m | ||||

| Warner et al. | 2005 | Retrospective | ASR | USA | 9 | 4/5 | 53y | 44m |

| MOR | 12 | 4/8 | 55y | 44m | ||||

| Youm et al. | 2005 | Retrospective | ASR | USA | 42 | NG | 60y | 37.6m |

| MOR | 42 | 59y | 37.6m | |||||

| Zhang et al. | 2014 | RCT | ASR | China | 55 | 27/28 | 53.9y | 29.4m |

| MOR | 53 | 26/27 | 54.2y | 29.4m | ||||

| Zwaal et al. | 2013 | RCT | ASR | The Netherlands | 47 | 18/29 | 57.2y | 56w |

| MOR | 48 | 20/28 | 57.8y | 56w |

RCT: Randomized controlled trial; ASR: Arthroscopic Repair; MOR: Mini-open repair; Y: Years; M: Months; W: Weeks.

Patient demographics

The summary of patient demographics for all included studies is presented in Table 1. Preoperative patient characteristics did not show any significant difference between these two groups with respect to the number of patients, gender and age.

Outcome Measurements

The results of standardized mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each comparison were shown in Table 2. Data at the study endpoint was pooled directly without stratifying for the study period due to considerable variability in the time period of follow-up in the included studies. Analyzable data was only reported in limited studies, which might contribute bias to our final results.

Table 2. Outcome measures in the meta-analysis of comparisons between all arthroscopic and mini-open cuff tear repair.

| Outcome | SMD (95% CI); p-value | Heterogeneity | I2% | Number of patients | Number of studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abduction | 1.174 (−1.019, 3.367); p = 0.294 | <0.0001 | 94.7 | 104 | 2studies (Kasten 2011, Verma 2006) |

| ASES score | 0.136 (−0.068, 0.340); p = 0.192 | 0.599 | 0.0 | 372 | 5studies (Kasten 2011, Kim 2003, Verma 2006, Youm 2005, Zhang 2014) |

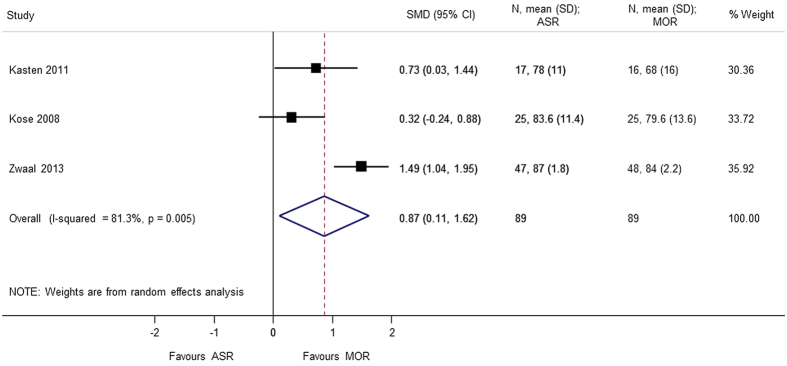

| Constant score | 0.865 (0.109, 1.621); p = 0.025 | 0.005 | 81.3 | 178 | 3studies (Kasten 2011, Kose 2008, Zwaal 2013) |

| Constant score (sensitivity analysis) | 0.477 (0.039, 0.915); p = 0.033 | 0.366 | 0.0 | 83 | 2 studies (Kasten 2011, Kose 2008) |

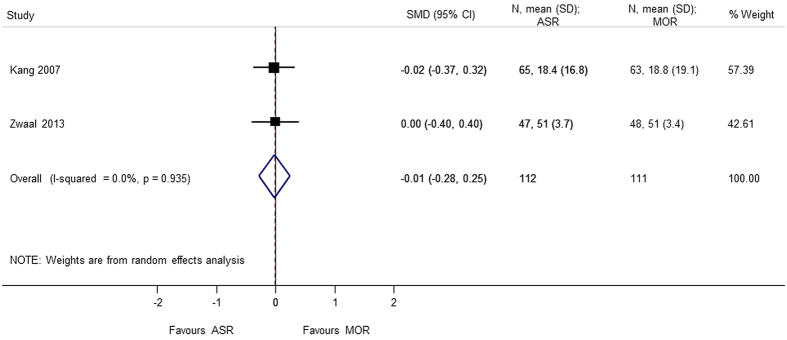

| DASH | −0.013 (−0.275, 0.250); p = 0.924 | 0.935 | 0.0 | 223 | 2studies (Kang 2007, Zwaal 2013) |

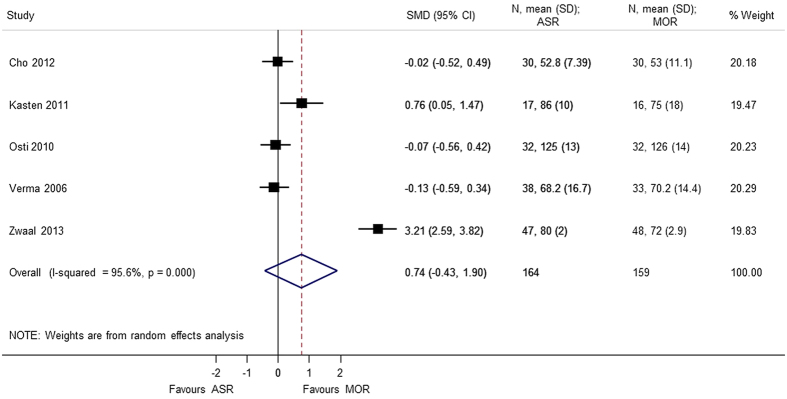

| External rotation | 0.740 (−0.426, 1.905); p = 0.213 | <0.0001 | 95.6 | 323 | 5studies (Cho 2012, Kasten 2011, Osti 2010, Verma 2006, Zwaal 2013) |

| External rotation (sensitivity analysis) | 0.065 (−0.268, 0.398); p = 0.703 | 0.192 | 36.7 | 228 | 4studies (Cho 2012, Kasten 2011, Osti 2010, Verma 2006) |

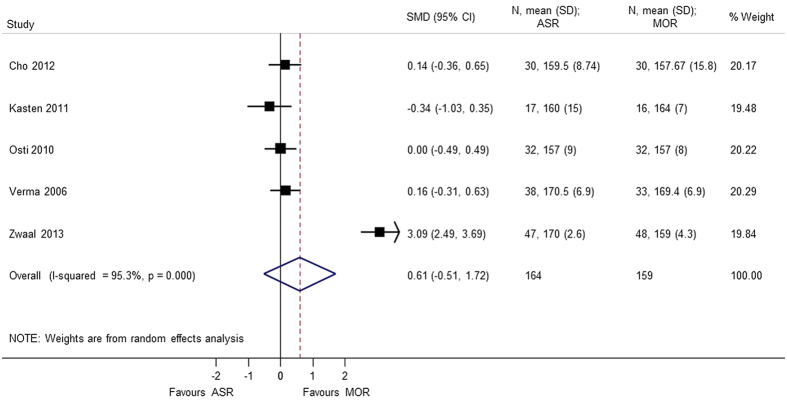

| Forward flextion | 0.608 (−0.506, 1.722); p = 0.285 | <0.0001 | 95.3 | 323 | 5 studies (Cho 2012, Kasten 2011, Osti 2010, Verma 2006, Zwaal 2013) |

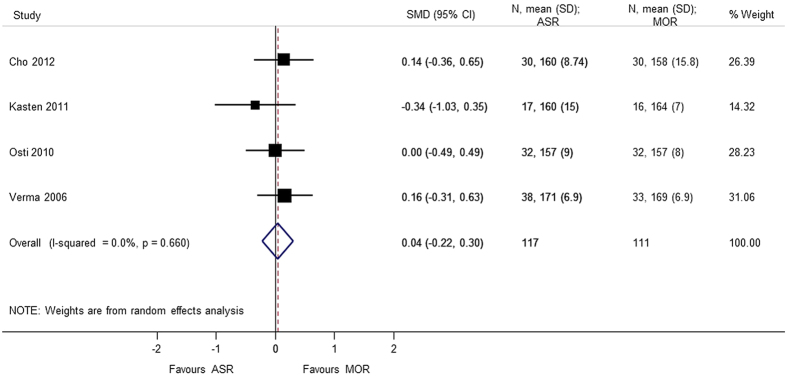

| Forward flextion (sensitivity analysis) | 0.039 (−0.221, 0.299); p = 0.770 | 0.660 | 0.0 | 228 | 4 studies (Cho 2012, Kasten 2011, Osti 2010, Verma 2006) |

| Internal rotation | 0.058 (−0.231, 0.347); p = 0.694 | 0.761 | 0.0 | 185 | 3 studies (Kose 2008, Osti 2010, Verma 2006) |

| SF-36 (bodily pain) | 0.044 (−0.239, 0.327); p = 0.759 | 0.608 | 0.0 | 192 | 2 studies (Kang 2007, Osti 2010) |

| SF-36 (role-physical) | −0.023 (−0.377, 0.331); p = 0.898 | 0.227 | 31.5 | 192 | 2 studies (Kang 2007, Osti 2010) |

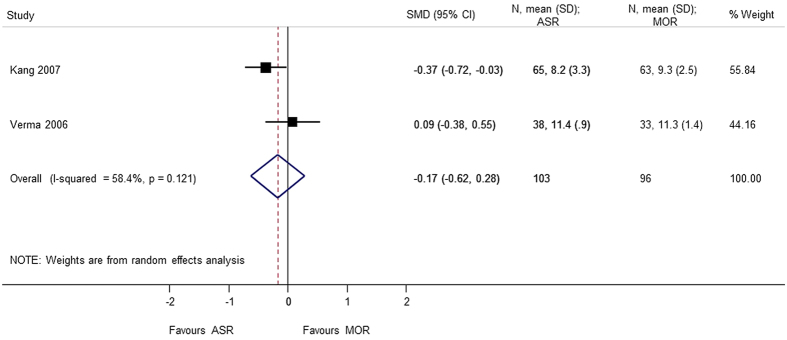

| SST | −0.171 (−0.620, 0.278); p = 0.455 | 0.121 | 58.4 | 199 | 2 studies (Kang 2007, Verma 2006) |

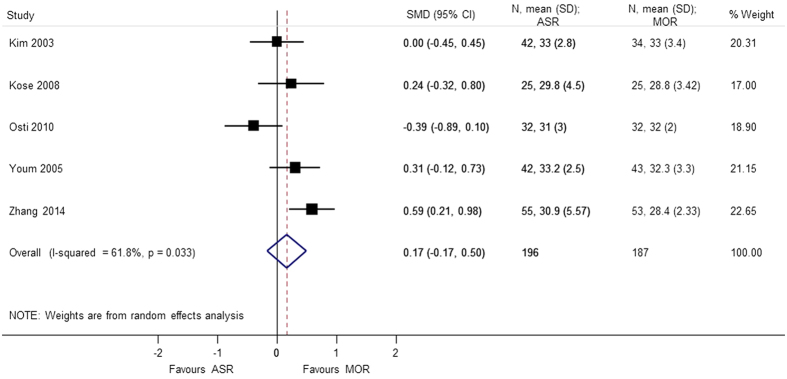

| UCLA score | 0.165 (−0.166, 0.497); p = 0.328 | 0.033 | 61.8 | 383 | 5 studies (Kim 2003, Kose 2008, Osti 2010, Youm 2005, Zhang 2014) |

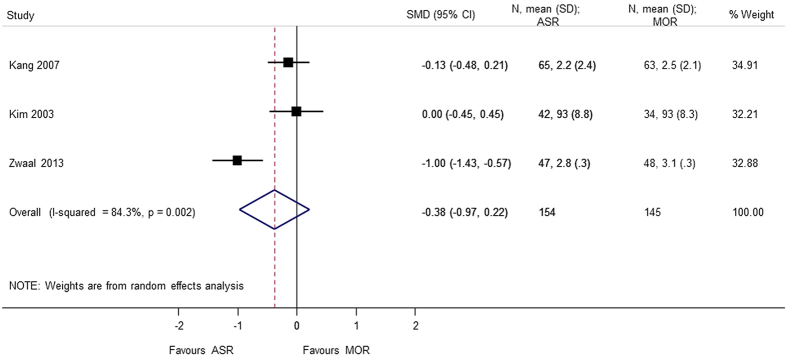

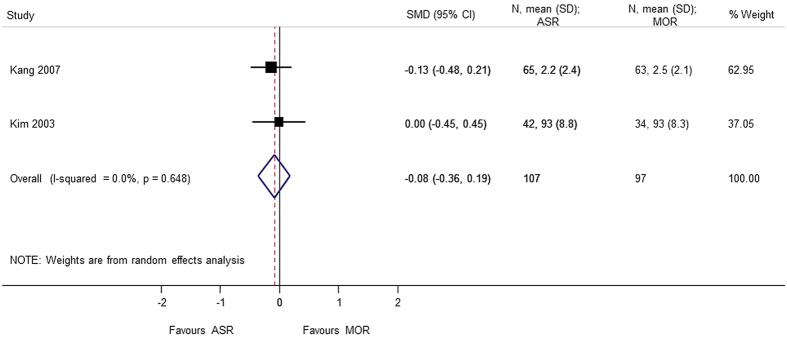

| VAS (function) | −0.375 (−0.968, 0.217); p = 0.214 | 0.002 | 84.3 | 299 | 3 studies (Kang 2007, Kim 2003, Zwaal 2013) |

| VAS (function) (sensitivity analysis) | −0.084 (−0.359, 0.192); p = 0.551 | 0.648 | 0.0 | 204 | 2 studies (Kang 2007, Kim 2003) |

| VAS (pain) | −0.206 (−0.775, 0.364); p = 0.479 | <0.0001 | 88.5 | 460 | 6 studies (Cho 2012, Kang 2007, Kasten 2011, Kim 2003, Verma 2006, Zwaal 2013) |

ASES: American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons’ Scoring Survey; SST: Simple Shoulder Test; UCLA: University of California, Los Angeles scoring scale.

Functional Results (UCLA Score, ASES Score, Constant Score, SST, DASH)

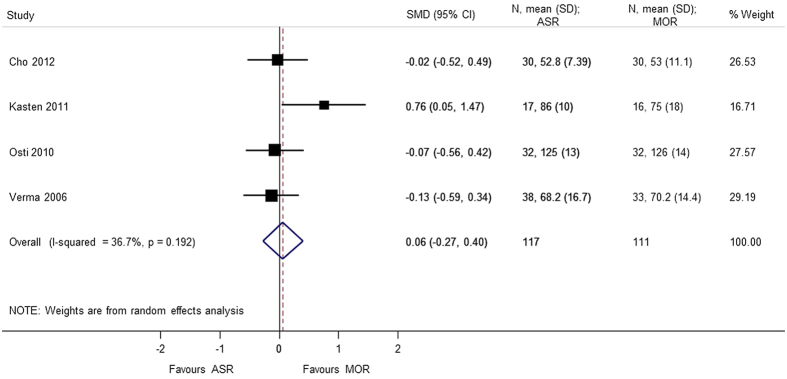

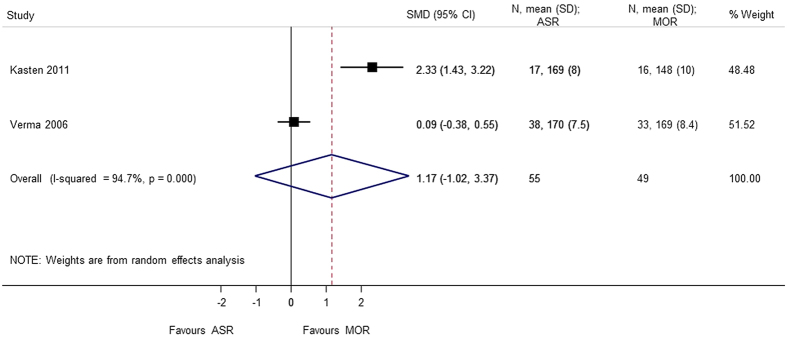

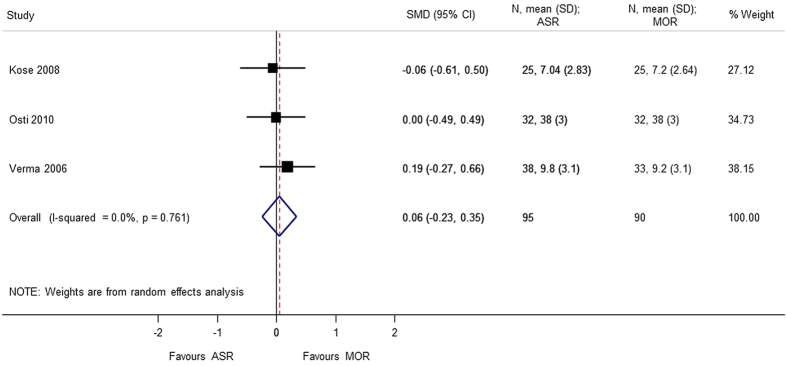

Nine studies4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 using different score systems were involved when comparing the function score between two groups. Constant score was significantly better in mini-open repair group (SMD = 0.865 95% CI 0.109, 1.621); p = 0.025. However, there was considerable heterogeneity in the results of Constant score and sensitivity analysis was conducted after removing Zwaal et al.9, and the results were still found to be significant (SMD = 0.477 95% CI 0.039, 0.915); p = 0.033. For the remaining functional scores; there was no difference between the arthroscopic group and mini-open repair group, at different periods of follow-up; UCLA (SMD = 0.165 95% CI −0.166, 0.497), ASES (SMD = 0.136 95% CI −0.068, 0.340), disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) (SMD = −0.013 95% CI −0.275, 0.250), and simple shoulder test (SST) (SMD = −0.171 95% −0.620, 0.278) (Figs 2, 3, 4, 5, 6). Several studies, in which only mean value was reported, were not included in the analysis. However, authors in these studies gave similar results as our outcome.

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI for UCLA (University of California Los Angeles) after surgery.

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI for ASES (American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons) after surgery.

Figure 4. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for constant score after surgery.

Figure 5. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for DASH (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand) score after surgery.

Figure 6. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for SST (Simple Shoulder Test) after surgery.

Range of Motion (Forward flexion, External Rotation, Internal rotation, Abduction)

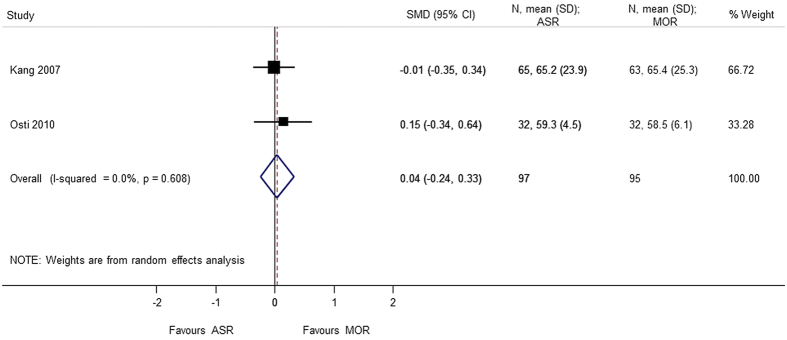

A total of 6 studies5,7,8,9,10,13 provided analyzable data for postoperative range of motion (Forward flexion, External rotation, Internal rotation, Abduction) with 373 patients. No statistical difference was observed in forward flexion (SMD = 0.608 95% CI −0.506, 1.722), external rotation (SMD = 0.740 95% CI −0.426, 1.905), internal rotation (SMD = 0.058 95% CI −0.231, 0.347), and abduction (SMD = 1.174 95% CI −1.019, 3.367). During analysis, heterogeneity (p < 0.0001) of the combined data was found for abduction, external rotation, and forward flexion. A sensitivity analysis was performed by removing the outliers. The heterogeneity decreased on removing the confounding study, Zwaal et al.9 and the results were consistent with the primary analysis with no statistical significant difference between arthroscopic repair and mini-open repair (Figs 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12). The heterogeneity could be explained by the fact that patients with simultaneous lesions of the shoulder were excluded in Zwaal et al.9.

Figure 7. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for forward flextion after surgery.

Figure 8. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for forward flextion after surgery (sensitivity analysis).

Figure 9. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for external rotation after surgery.

Figure 10. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for external rotation after surgery (sensitivity analysis).

Figure 11. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for abduction after surgery.

Figure 12. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for internal rotation after surgery.

Quality of life

Very few studies investigated the impact of arthroscopic and mini-open repair techniques on postoperative quality of life. SF-36, VAS, SF-12.

VAS Score (Pain, Function)

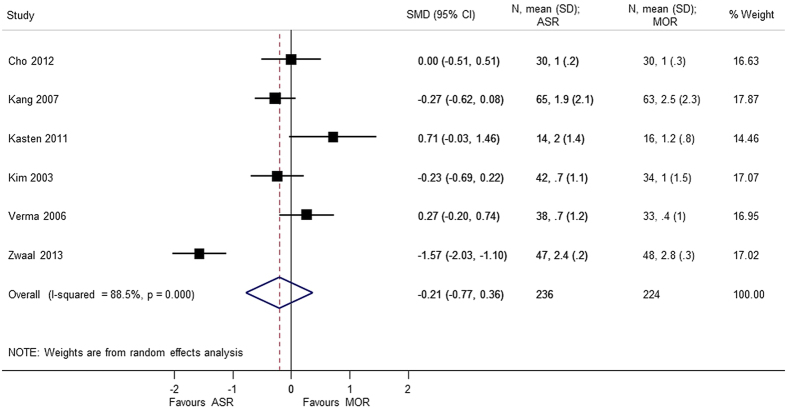

Six studies4,5,6,9,10,13 totaling to 460 patients were included for analysis of pain score and function using the visual analog scale (VAS). No significant difference were found between arthroscopic repair and mini-open repair on the VAS pain scale (SMD = −0.206 95% CI −0.775, 0.364) and VAS function scale (SMD = −0.084 95% CI −0.359, 0.192). A heterogeneity (p < 0.05) was found in the VAS analysis, and sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding the study by Zwaal et al.9. The reason might be attributed to arthroscopic development as discussed earlier (Figs 13, 14, 15).

Figure 13. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for VAS (Visual Analog Scale) (pain) after surgery.

Figure 14. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for VAS (Visual Analog Scale) (function) after surgery.

Figure 15. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for VAS (Visual Analog Scale) (function) after surgery (sensitivity analysis).

SF-36 (Bodily Pain, Role-Physical)

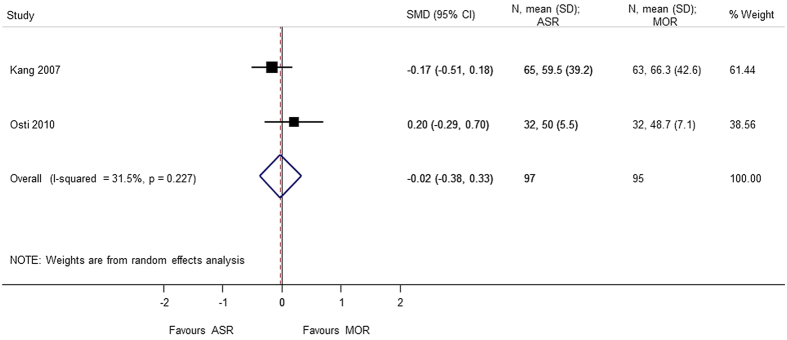

In addition to the VAS score, analysis on the SF-36 subscales of role-physical and bodily pain was also performed, to check whether the results were consistent across the two scales for the similar outcomes. Two studies4,8 with 192 patients contributing to the analysis of SF-36 subscales were included. There was no statically significant difference in the arthroscopic repair and mini-open repair on the bodily-pain (SMD = 0.044 95% CI −0.239, 0.327) and role-physical (SMD = −0.023 95% CI −0.377, 0.331) subscales of SF-36. The results are consistent with the VAS pain and VAS function scales (Figs 16 and 17).

Figure 16. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for SF-36 (Short-Form 36) (bodily pain) after surgery.

Figure 17. Forest plot showing the SMD (standardized mean difference) and 95% CI (Confidence Interval) for SF-36 (Short-Form 36) (role physical) after surgery.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is most up-to-date systematic review including 18 studies, including both randomized and observational studies comparing arthroscopic repair with mini-open rotator cuff repair. Earlier conducted systematic reviews focus on specific study designs, RCTs14 or observational study design15. While some other reviews include limited publications, 5 studies16 and 12 studies17.

The results of our review are consistent with the previously conducted systematic reviews14,15,16,17, concluding that the two techniques (mini-open rotator cuff repair and arthroscopic repair) have similar outcomes and can be considered as alternative treatment options. However, the result of our meta-analysis show that the Constant-Murley score (CMS) was significantly better in the mini-open repair group compared to all arthroscopic repair. CMS is a 100-points scale composed of four subscales: pain (15 points), activities of daily living (20 points), strength (25 points) and range of motion: forward elevation, external rotation, abduction and internal rotation of the shoulder (40 points). On a 100-points scale, higher score is related to higher quality of the function18.

Tear size is an important factor for achieving satisfactory results, with more patients with large or massive cuff tears obtaining unsatisfactory response outcomes19. Zhang et al. noted that patients treated with arthroscopic group displayed better shoulder strength but a significantly higher retearing rate as compared to mini-open group at 24-month follow-up12. For full-thickness tears, retearing rates were 74% for the arthroscopic group and 35% for the mini-open group (p < 0.05). For partial-thickness tears, no significant difference was detected12. Kim et al. conclude that surgical outcomes depend upon the size of the tear, rather than the method of repair6. The operative time for arthroscopic repair was also significantly longer than that for mini-open repair4.

In a study by Verma et al., there was no difference in the outcome measure for VAS (pain) and ASES score between the intact and failed repair group, indicating that excellent symptomatic relief can be achieved regardless of tendon healing. However, significant differences existed between intact and failed repairs in the restoration of forward flexion, showing an adequate repair remains vital, if strength is to be restored10.

Surgical technique had an impact on return to work, with an open procedure (66% patients) being advantageous compared to arthroscopic repair (45.3%) and mini-open repair (41.6%) (p = 0.004). However, there was no significant difference in the time away from work between the groups, even if it was slightly longer for open procedures20.

Warner et al. tested two hypotheses in a retrospective study evaluating 21 patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears21. First, that there was no difference in clinical outcome and patient satisfaction between single tendon tears repaired through mini-open repair (MOR) or arthroscopic repair (ASR) technique and second, that stiffness would be less and recovery would be faster with ASR. However, the results of the study support the first hypothesis but not the second hypothesis21. In a study by Chung et al. evaluating postoperative stiffness in 288 patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears, patients who underwent mini-open repair had more stiffness compared to all-arthroscopic group at the final follow-up (p = 0.02)22. However, there was no significant difference postoperative stiffness, pain scores, and range of motion in the two groups, in an RCT conducted by Cho et al.13.

Severud et al. noted that no patients in the arthroscopic group developed fibrous ankylosis, whereas 4 patients in the mini-open group developed the condition (14%), defined as failure to achieve greater than 120° forward flexion by 12 weeks postoperatively. The lower incidence of fibrous ankylosis favors the all-arthroscopic technique. A trend for better early motion was also noted in the all-arthroscopic group19.

Kose et al. reported preference of mini-open repair due to its low cost and high patient satisfaction, while also providing similar results to arthroscopic surgery7.

No statistically significant improvement was observed at six months in SF-36 general health, role-emotional, and mental health, in a retrospective study of 65 patients treated with arthroscopic rotator cuff repair and 63 treated with mini-open rotator cuff repair4. Similarly, in a case-control study design to report on 52 patients treated with either technique, the SF-36 was not significantly different postoperatively between the two groups23. However, in a retrospective study conducted by Osti et al., evaluating the two techniques in 64 patients with rotator cuff tears less than 3 cm, postoperative assessment showed a statistically significant improvement in the self-administered SF-36 scores from the preoperative values at 6 months8. The differences could be due to patient selection in individual studies, further, Osti et al. compared only rotator cuff tears with similar size and similar fixation (suture anchor)8.

Limitations

The review includes both RCTs and retrospective studies, with more number of studies having retrospective study design. However, this may be due to the lack of RCT studies conducted in this area, as an unbiased methodology was used for study selection and inclusion irrespective of the study design. There were also differences in time to follow up postoperatively, with studies ranging from 6 months4,5,13 to 50.6 months23. Further, we did not investigate the impact of tear size on the outcomes, with population consisting of patients with partial-thickness rotator cuff tears less than 3 cm and full-thickness rotator cuff tears larger than 3 cm. Both single-row and double-row fixation techniques have been widely used for rotator cuff tears. Differentiation based on the use of fixation techniques was not investigated in this review, due to limitation of evidence reporting the impact of the techniques. However, in a meta-analysis it has been found that double-row fixation technique is associated with increase in post-operative rotator cuff integrity and improved clinical outcomes, especially in patients with tears larger than 3 cm24,25,26. Also, arthroscopic procedures were performed during the transition from mini-open to all-arthroscopic techniques; consequently, this occurred early in the learning curve in majority of the studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, arthroscopy repair and mini-open repair are associated with similar clinical outcomes. The choice of the operating technique depends upon the tear size and surgeon’s preference. Future research should focus on tear patterns, size, degree of delamination, mobility, and outcomes from surgical repair.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Huang, R. et al. Systematic Review of All-Arthroscopic Versus Mini-Open Repair of Rotator Cuff Tears: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 22857; doi: 10.1038/srep22857 (2016).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 31300137 and 81401423). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.S., R.H. and S.W. were responsible for study design, data extraction, and reporting; R.H., Y.W. and X.Q. contributed to the study concept, design, and data interpretation. All authors contributed to the development of and review of the draft manuscript, and approved the final submitted version.

References

- Beaudreuil J., Dhénain M., Coudane H. & Mlika-Cabanne N. Clinical practice guidelines for the surgical management of rotator cuff tears in adults. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 96, 175–179 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huisstede B. M., Koes B. W., Gebremariam L., Keijsers E. & Verhaar J. A. Current evidence for effectiveness of interventions to treat rotator cuff tears. Manual therapy 16, 217–230 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey V. & Willems W. J. Rotator cuff tear: A detailed update. Asia-Pacific Journal of Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation and Technology 2, 1–14 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang L., Henn R. F., Tashjian R. Z. & Green A. Early outcome of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a matched comparison with mini-open rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 23, 573–582. e572 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasten P. et al. Prospective randomised comparison of arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair of the supraspinatus tendon. International orthopaedics 35, 1663–1670 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.-H. et al. Arthroscopic versus mini-open salvage repair of the rotator cuff tear: outcome analysis at 2 to 6 years’ follow-up. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 19, 746–754 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köse K. Ç. et al. Mini-open versus all-arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: comparison of the operative costs and the clinical outcomes. Advances in therapy 25, 249–259 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osti L., Papalia R., Paganelli M., Denaro E. & Maffulli N. Arthroscopic vs mini-open rotator cuff repair. A quality of life impairment study. International orthopaedics 34, 389–394 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zwaal P. et al. Clinical outcome in all-arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair in small to medium-sized tears: a randomized controlled trial in 100 patients with 1-year follow-up. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 29, 266–273 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma N. N. et al. All-arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a retrospective review with minimum 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 22, 587–594 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youm T., Murray D. H., Kubiak E. N., Rokito A. S. & Zuckerman J. D. Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a comparison of clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery 14, 455–459 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Gu B., Zhu W., Zhu L. & Li Q. Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a prospective, randomized study with 24-month follow-up. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology 24, 845–850 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung G.-H., Lee Y.-K. & Shin H.-K. Early postoperative outcomes between arthroscopic and mini-open repair for rotator cuff tears. Orthopedics (Online) 35, e1347 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X., Bi C., Wang F. & Wang Q. Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: an up-to-date meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 31, 118–124 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.-J., Song Y.-C., Fang R. & Hong H.-G. Comparison of therapeutic effect of arthroscope versus mini-open in treating rotator cuff impairment: A meta-analysis. Chinese Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine 10:10, 1222–1227 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Morse K. et al. Arthroscopic Versus Mini-open Rotator Cuff Repair A Comprehensive Review and Meta-analysis. The American journal of sports medicine 36, 1824–1828 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan L., Fu D., Chen K., Cai Z. & Li G. All-arthroscopic versus mini-open repair of small to large sized rotator cuff tears: a meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. PloS one 9, e94421 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy J.-S., MacDermid J. C. & Woodhouse L. J. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the Constant-Murley score. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 19, 157–164 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severud E. L., Ruotolo C., Abbott D. D. & Nottage W. M. All-arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a long-term retrospective outcome comparison. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 19, 234–238 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nove-Josserand L. et al. Occupational outcome after surgery in patients with a rotator cuff tear due to a work-related injury or occupational disease. A series of 262 cases. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 97, 361–366 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner J. J., Tétreault P., Lehtinen J. & Zurakowski D. Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: a cohort comparison study. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 21, 328–332 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S. W., Huong C. B., Kim S. H. & Oh J. H. Shoulder stiffness after rotator cuff repair: risk factors and influence on outcome. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 29, 290–300 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearsall A. W., Ibrahim K. A. & Madanagopal S. G. The results of arthroscopic versus mini-open repair for rotator cuff tears at mid-term follow-up. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research 2, 24 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. et al. Single-row or double-row fixation technique for full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a meta-analysis. PloS one 8, e68515 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Zhao J. & Li D. Meta-analysis comparing single-row and double-row repair techniques in the arthroscopic treatment of rotator cuff tears. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 23, 182–188 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett P. J., Warth R. J., Dornan G. J., Lee J. T. & Spiegl U. J. Clinical and structural outcomes after arthroscopic single-row versus double-row rotator cuff repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis of level I randomized clinical trials. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 23, 586–597 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]