Introduction

AF ablation remains disappointing – despite spectacular results in individual patients –for both persistent and paroxysmal AF using contemporary catheters1. The benefits of pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) likely extend beyond isolating triggers – since ablation may be more successful if wide areas are ablated by radiofrequency or cryoballoons2, and patients without AF may have reconnected PVs3. Hence it seems intuitive that additional lesion sets should improve outcomes.

However, several meta-analyses have suggested that commonly applied ablation sets beyond PVI provide inconsistent benefit4. This was illustrated vividly by the STAR-AF2 trial, in which the 59% success of PVI was not improved by adding lines or CFAE5. However, a major criticism of STAR-AF2 is that lines were not blocked in 26% of patients.

Into this area comes the BOCA (No Benefit OF Complex Fractionated Atrial Electrogram (CFAE) Ablation in Addition to Circumferential Pulmonary Vein Ablation and Linear Ablation) trial of ablation strategies for persistent and longstanding persistent AF in this issue of Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology6. BOCA addresses 2 unanswered questions – what is ablation success when lines are proven to be complete, and what is the value of supplementary widespread ablation (CFAE) if lines are blocked?

In BOCA, the investigators prospectively randomized 131 persistent AF patients in 1:1 fashion to PVI + Lines (roof and mitral, “control”) or PVI+ lines + CFAE (“CFAE”) in a single center. Conduction block was confirmed in 95% of mitral lines and 100% of roof lines and PVI. Notably, patients in the CFAE arm had no advantage over the control arm, with similar single (46.2% vs. 56.9%, p=0.20) and multi-procedure (78% vs. 80%, p=1.0) freedom from atrial arrhythmias at 12 months. Patients in the CFAE limb experienced more atrial flutters, and had longer procedural and ablation times.

The authors should be commended on designing and executing this important trial. Their success compares favorably with STAR-AF2, particularly given that many patients had LV systolic dysfunction, elevated BMI and long standing persistent AF. Limitations include the fact that follow-up using ambulatory ECGs only at 12 months could easily miss asymptomatic recurrences, that block across PVI and/or lines was not verified with adenosine and that contact force sensing was not used. However, these factors would influence both limbs similarly. Taken in context, results from the BOCA6 and STAR-AF25 trials suggest that PVI produces at least equivalent success with less ablation than PVI+lines, PVI+CFAE or PVI+lines+CFAE in persistent AF. The overwhelming message that `less is more' for AF ablation gives us pause to reflect upon which AF mechanisms are ablated by current lesion sets.

Possible Mechanisms By Which Lines/CFAE May Not Improve PVI

If AF is due to disordered wavelets that self-sustain, as hypothesized by Moe from computer models7, then lines and additional lesions should dramatically reduce the tissue available for these wavelets and should thus improve outcomes.

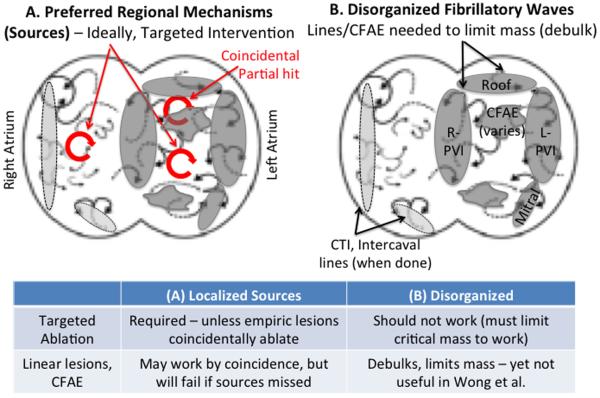

The figure shows a conceptual schematic of AF driven by 2 fundamental mechanisms: (a) Preferred regional mechanisms (sources) driving disorganized waves or (b) disorganized wavelets that self-sustain, i.e. without preferred regional sources, such as the multiple-wavelet7 or endo-epi dissociation8 hypotheses. Ablation lesions are shown in gray shading, and may operate by hitting sources (figure 1A) or by constraining disordered wavelets (figure 1B) as shown in the table.

Figure.

Organized and disorganized mechanisms of AF. The failure of extensive ablation to improve AF outcomes in BOCA and STAR-AF2 is better explained by (A) preferred regional sources that can be missed by ablation, than (B) meandering multiple wavelets that would be constrained by greater ablation.

It is in fact questioned whether self-sustaining disorder (figure 1B) is a key mechanism for AF. Reports of AF caused simply by “complexity”8 often ignore data that activation shows consistent patterns in AF9 or that localized ablation can terminate persistent AF10, and typically examined <10% of atrial area without mechanistic interventions8 Since successful therapy for self-sustaining disordered AF must compartmentalize the atrium, its strongest support has come from the need for extensive ablation11. One could thus argue that lines applied in BOCA and STAR-AF2 were insufficient to limit atrial mass, yet this does not explain the success of limited ablation10, or how in the Bordeaux stepwise approach11 the first steps were often successful yet patients with the longest ablation times often had the worst acute and long-term outcomes – all of which argue against this mechanism.

Conversely, mounting data supports the concept that disorganized activity in AF is maintained by spatially preferred mechanisms (sources) which, in the majority of optical mapping studies, take the form of localized rotors that produce disorder. In recent human optical mapping studies, AF was sustained by stable endocardial micro-reentrant sources anchored to muscle bundles that produced unstable breakthroughs and rotations on the epicardium abolished by endocardial ablation12. These optical data support results from wide-area contact basket mapping10, and may reconcile the instability of sources on ECG imaging of the epicardium13.

If AF Is Due To Localized Sources, Shouldn't Lines Hit Some Of Them?

In the CONFIRM trial10, stereotypical lines sometimes hit sources, but also often missed sources that lay in patient-specific locations with small areas of 1–2 cm2 on endocardial optical12 and basket maps10 (figure 1A). Since studies increasingly show that persistent AF is a bi-atrial disease, with a third of sources occur in the right atrium on endocardial or epicardial mapping10,13, ablation lines in CONFIRM intersected only 40–60% of sources, and such patients had substantially higher success than those in whom sources were missed14.

Shouldn't CFAE Ablation Hit Some Sources, and Are Widespread Lesions Pro-Arrhythmic?

CFAE are increasingly felt to be mechanistically non-specific, because electrograms in AF may poorly reflect local activation15 and because CFAE-algorithms vary16. CFAE ablation is often patchy and scattered, and while its impact on clinical rotors is unclear, in animal models such lesions destabilize rotors17 possibly by creating additional attractors. This adds to the concern that widespread ablation is pro-arrhythmic, also shown by the high incidence of atrial tachycardia after CFAE ablation in BOCA and STAR-AF2.

The Path Forwards: Patient-Specific Mapping of AF

Given ample evidence that “less is more” in AF ablation, is there a way to improve the current 50–60% success? A nihilistic view – that outcomes cannot be improved – is at odds with abundant anecdotes of success when ablating AF outside the PVs. To solidify these anecdotes into “personalized ablation”, a promising approach is to target ablation to mapped AF mechanisms in each patient. Wide area basket mapping shows that AF is often maintained by stable rotors and focal sources10, with similarities to recent human optical mapping studies12, whose ablation is promising in multicenter non-randomized studies18. While AF sources have been questioned, those studies had issues such as atrial cycle lengths of 250–500ms (dominant frequencies 2–4 Hz) in many patients ostensibly with AF and analysis of unipolar signals using indices designed for bipolar signals (Shannon's entropy)19, or mapped very small areas8. Recent data showing how localized ablation can terminate AF rotors, by interacting with non-uniformities in remodeled atria, explain and thus strengthen the results of AF source ablation20. At the other end of the spectrum, it has been proposed that debulking should be further extended – such as by posterior LA wall ablation. Limitations of this approach include the fact that recurrences still occur, that targeting right atrial sources will require essentially bi-atrial obliteration, and a risk of sequelae including but not limited to stiff left atrial syndrome.

Conclusions

The BOCA trial shows that non-targeted debulking of atrial tissue, based on early assumptions that AF is a random process, has repeatedly failed to advance patient outcomes. A promising emerging direction, based on mounting evidence that human AF is sustained by localized sources in both atria, is to personalize ablation based on map guided mechanisms. It is time to translate decades of basic and translational science to the bedside to improve AF ablation – our field requires it and our patients demand it.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Zaman was supported by the Fulbright Commission and British Heart Foundation (FS/14/46/30907). Dr. Narayan was supported in part by grants from the NIH (R01 HL 83359, K24 HL103800). Dr. Narayan reports being co-inventor on intellectual property owned by the University of California and licensed to Topera Medical, Inc., in which he has held equity. Dr. Narayan reports having received consulting fees from the American College of Cardiology, Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, UpToDate and Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Zaman reports no conflicts.

References

- 1.Calkins H. Demonstrating the Value of Contact Force Sensing: More Difficult Than Meets the Eye. Circulation. 2015;132:901–903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenigsberg DN, Martin N, Lim HW, Kowalski M, Ellenbogen KA. Quantification of the cryoablation zone demarcated by pre- and postprocedural electroanatomic mapping in patients with atrial fibrillation using the 28-mm second-generation cryoballoon. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang RH, Po SS, Tung R, Liu Q, Sheng X, Zhang ZW, Sun YX, Yu L, Zhang P, Fu GS, Jiang CY. Incidence of pulmonary vein conduction recovery in patients without clinical recurrence after ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: mechanistic implications. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:969–976. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wynn GJ, Das M, Bonnett LJ, Panikker S, Wong T, Gupta D. Efficacy of catheter ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of evidence from randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7:841–852. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verma A, Jiang CY, Betts TR, Chen J, Deisenhofer I, Mantovan R, Macle L, Morillo CA, Haverkamp W, Weerasooriya R, Albenque JP, Nardi S, Menardi E, Novak P, Sanders P, STAR AF II Investigators Approaches to catheter ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1812–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong KC, Paisey JR, Sopher M, Balasubramaniam R, Jones M, Qureshi N, Hayes CR, Ginks MR, Rajappan K, Bashir Y, Betts TR. No Benefit OF Complex Fractionated Atrial Electrogram (CFAE) Ablation in Addition to Circumferential Pulmonary Vein Ablation and Linear Ablation: BOCA Study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:XXX–XXX. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moe GK, Rheinboldt WC, Abildskov JA. A Computer Model of Atrial Fibrillation. Am Heart J. 1964;67:200–220. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(64)90371-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Groot NM, Houben RP, Smeets JL, Boersma E, Schotten U, Schalij MJ, Crijns H, Allessie MA. Electropathological substrate of longstanding persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with structural heart disease: epicardial breakthrough. Circulation. 2010;122:1674–1682. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.910901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walters TE, Lee G, Morris G, Spence S, Larobina M, Atkinson V, Antippa P, Goldblatt J, Royse A, O'Keefe M, Sanders P, Morton JB, Kistler PM, Kalman JM. Temporal Stability of Rotors and Atrial Activation Patterns in Persistent Human Atrial FibrillationA High-Density Epicardial Mapping Study of Prolonged Recordings. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;1:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narayan SM, Krummen DE, Shivkumar K, Clopton P, Rappel WJ, Miller JM. Treatment of atrial fibrillation by the ablation of localized sources: CONFIRM (Conventional Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation With or Without Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:628–636. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haïssaguerre M, Sanders P, Hocini M, Takahashi Y, Rotter M, Sacher F, Rostock T, Hsu LF, Bordachar P, Reuter S, Roudaut R, Clémenty J, Jaïs P. Catheter ablation of long-lasting persistent atrial fibrillation: critical structures for termination. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16:1125–1137. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen BJ, Zhao J, Csepe TA, Moore BT, Li N, Jayne LA, Kalyanasundaram A, Lim P, Bratasz A, Powell KA, Simonetti OP, Higgins RS, Kilic A, Mohler PJ, Janssen PM, Weiss R, Hummel JD, Fedorov VV. Atrial fibrillation driven by micro-anatomic intramural re-entry revealed by simultaneous sub-epicardial and sub-endocardial optical mapping in explanted human hearts. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2390–2401. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haissaguerre M, Hocini M, Denis A, Shah AJ, Komatsu Y, Yamashita S, Daly M, Amraoui S, Zellerhoff S, Picat M-Q, Quotb A, Jesel L, Lim H, Ploux S, Bordachar P, Attuel G, Meillet V, Ritter P, Derval N, Sacher F, Bernus O, Cochet H, Jais P, Dubois R. Driver domains in persistent atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2014;130:530–538. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narayan SM, Krummen DE, Clopton P, Shivkumar K, Miller JM. Direct or coincidental elimination of stable rotors or focal sources may explain successful atrial fibrillation ablation: on-treatment analysis of the CONFIRM trial (Conventional ablation for AF with or without focal impulse and rotor modulation) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narayan SM, Wright M, Derval N, Jadidi A, Forclaz A, Nault I, Miyazaki S, Sacher F, Bordachar P, Clémenty J, Jaïs P, Haïssaguerre M, Hocini M. Classifying fractionated electrograms in human atrial fibrillation using monophasic action potentials and activation mapping: evidence for localized drivers, rate acceleration, and nonlocal signal etiologies. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:244–253. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau DH, Maesen B, Zeemering S, Kuklik P, van Hunnik A, Lankveld TA, Bidar E, Verheule S, Nijs J, Maessen J, Crijns H, Sanders P, Schotten U. Indices of Bipolar Complex Fractionated Atrial Electrograms Correlate Poorly with Each Other and Atrial Fibrillation Substrate Complexity. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1415–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamazaki M, Avula UMR, Berenfeld O, Kalifa J. Mechanistic Comparison of “Nearly Missed” Versus “On-Target” Rotor Ablation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;1:256–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller JM, Kowal RC, Swarup V, Daubert JP, Daoud EG, Day JD, Ellenbogen KA, Hummel JD, Baykaner T, Krummen DE, Narayan SM, Reddy VY, Shivkumar K, Steinberg JS, Wheelan KR. Initial Independent Outcomes from Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation: Multicenter FIRM Registry. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2014;25:921–929. doi: 10.1111/jce.12474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benharash P, Buch E, Frank P, Share M, Tung R, Shivkumar K, Mandapati R. Quantitative Analysis of Localized Sources Identified by Focal Impulse and Rotor Modulation Mapping in Atrial Fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:554–561. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.002721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rappel WJ, Zaman JA, Narayan SM. Mechanisms For the Termination of Atrial Fibrillation by Localized Ablation: Computational and Clinical Studies. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015 Sep 10; doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.115.002956. pii: CIRCEP.115.002956. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]