SUMMARY

In response to the global effort to accelerate progress towards the Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5, a partnership was created between the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to establish the Global Network for Women's and Children's Health Research (Global Network) in 2000. The Global Network was developed with a goal of building local maternal and child health research capacity in resource-poor settings. The objective of the network was to conduct research focused on several high-need areas, such as preventing life-threatening obstetric complications, improving birth weight and infant growth, and improving childbirth practices in order to reduce mortality. Scientists from developing countries, together with peers in the USA, lead research teams that identify and address population needs through randomized clinical trials and other research studies. Global Network projects develop and test cost-effective, sustainable interventions for pregnant women and newborns and provide guidance for national policy and for the practice of evidence-based medicine. This article reviews the results of the Global Network's research, the impact on policy and practice, and highlights the capacity-building efforts and collaborations developed since its inception.

Keywords: Global health, Maternal and child health, Low–middle income countries

1. Introduction

Maternal and newborn mortality and stillbirth rates have remained high in low resource settings, with only slow progress in reaching goals to reduce these mortalities [1–3]. In response to this need, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) founded a research network in 2000. Initially, the Global Network for Women's and Children's Health Research (Global Network) included 10 sites and a Data Coordinating Center (DCC) and conducted individual site studies of interventions focused on problems in pregnancy and birth [4–12]. Today, the Global Network comprises seven research sites and focuses on community-based common protocols, conducted at three or more sites, which address major maternal and newborn health challenges with the goal of developing low cost, sustainable interventions to improve maternal and child health and simultaneously build local research capacity and infrastructure [13–24]. This unique position gives Global Network the ability to identify gaps between science and practice. Each study examines either a novel evidence-based treatment or an innovative use of a proven treatment to improve the health, well-being, and survival of pregnant women, fetuses, and infants. All studies conform to US and international ethical and safety guidelines. More than twenty trials have been conducted by investigators within the network since its inception (Table 1).

Table 1.

Global Network for Women's and Children's Health Research: studies.

| Principal investigator | Field sites | |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-site studies | ||

| First Breath: a community-based cluster randomized trial of Neonatal Resuscitation Training in Developing Countries | Waldemar Carlo | Guatemala, DRC, Zambia, India (Orissa, Belgaum), Pakistan |

| First Bites: complementary feeding a Global Network Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial | Michael Hambidge | Guatemala, DRC, Zambia, Pakistan |

| Verbal autopsy of perinatal deaths | Cyril Engmann | Guatemala, DRC, Zambia, Pakistan |

| BRAIN Home-based Intervention Trial | Waldemar Carlo | Belgaum, India, Pakistan, Zambia |

| EMONC (Emergency Obstetric Maternal and Neonatal Care): a combined community- and facility-based approach to improve pregnancy outcomes in low-resource settings | Robert Goldenberg, Omrana Pasha | Argentina, India (Belgaum, Nagpur), Kenya, Zambia, Pakistan, Guatemala |

| Maternal and neonatal health registry | Carl Bose, Waldemar Carlo | India (Belgaum, Nagpur), Kenya, Zambia, Pakistan, Guatemala, DRC |

| Antenatal Corticosteroid Trial | Pierre Buekens, Jose Belizan, Fernando Althabe | Argentina, India (Belgaum, Nagpur), Kenya, Zambia, Pakistan, Guatemala |

| The Intrapartum Indicator: pilot study | Robert Goldenberg | Guatemala, Pakistan, India (Belgaum and Nagpur), DRC |

| Survey of Tobacco Use among Pregnant Women | Robert Goldenberg, Michele Bloch | Argentina, Brazil, Guatemala, DRC, Zambia, India (Orissa, Belgaum), Pakistan |

| Survey of Community Birth Attendants: Knowledge, Care and Practices | Ana Garces | Argentina, Guatemala, DRC, Zambia, Belgaum, India, Pakistan |

| Women First: Preconception Nutritiona | Nancy Krebs, Michael Hambidge, Ana Garces | Guatemala, Pakistan, India (Belgaum), DRC |

| First Look: Ultrasound at Antenatal Carea | Robert Goldenberg, Elizabeth McClure | DRC, Guatemala, Kenya, Pakistan, Zambia |

| Aspirin to reduce preterm birthb | Richard Derman, Matthew Hoffman, Shiva Goudar | India (Belgaum and Nagpur), Kenya, Zambia, Pakistan, Guatemala, DRC |

| Single site research (completed) | ||

| Clustered Trial for Improving Perinatal Care in Uruguay/Argentina | Jose Belizan, Pierre Buekens | Argentina |

| Safe Pregnancy by Infectious Disease Control in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo: Pilot Study and Biologic Specimen | Antointte Tshefu, Robin Ryder | DRC |

| Neonatal Resuscitation in Zambia | Elwyn Chomba, Waldemar Carlo | Zambia |

| Systematic Pediatric Care for Oral Clefts in South America | Ed Castilla, Jeff Murray, | South America |

| Oral Cleft Prevention Trial in Brazil | Ed Castilla, Jeff Murray, | South America |

| Cluster Randomized Trial of Antioxidant Therapy to Prevent Preeclampsia in Brazil | Freire, Joe Spinnato | Brazil |

| Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial (RPCT) of Maize/Zinc in Guatemala | Manolo Mazariegas, Michael Hambidge | Guatemala |

| Prevention of Infection in Indian Neonates: Phase II Probiotics Study | S.N. Parida, Pinaki Panigrahi | Orissa, India |

| Randomized controlled trial of Misoprostol for Postpartum Hemorrhage in India | Bhala Kodkany, Richard Derman | Belgaum, India |

| Study of Perinatal Outcomes in Pakistan | Rozina Karmaliani, Omrana Pasha, Robert Goldenberg | Pakistan |

| Chlorhexidine Wash to Prevent Neonatal and Maternal Mortality in Pakistan | Sarah Saleem, Robert Goldenberg | Pakistan |

| Zhi Byed 11 (ZB11) versus Misoprostol in Tibet | Michael Varner | Tibet |

| Caterpillar as a complementary food | Carl Bose | DRC |

| Chicken liver as a complementary food | Omrana Pasha, Robert Goldenberg | Pakistan |

| Monkeypox surveillance | Anne Rimoin | DRC |

Trial underway.

Trial in development.

2. Our mission

The overall goal of the Global Network is to expand the scientific knowledge relevant to improving health outcomes for women and children in low income countries. This has been achieved through the development of sustainable research infrastructure and public health intervention capabilities in low–middle income countries and strengthened international collaborative research efforts that focus on the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in pregnancy and early childhood.

3. Successful collaborative research unit structure

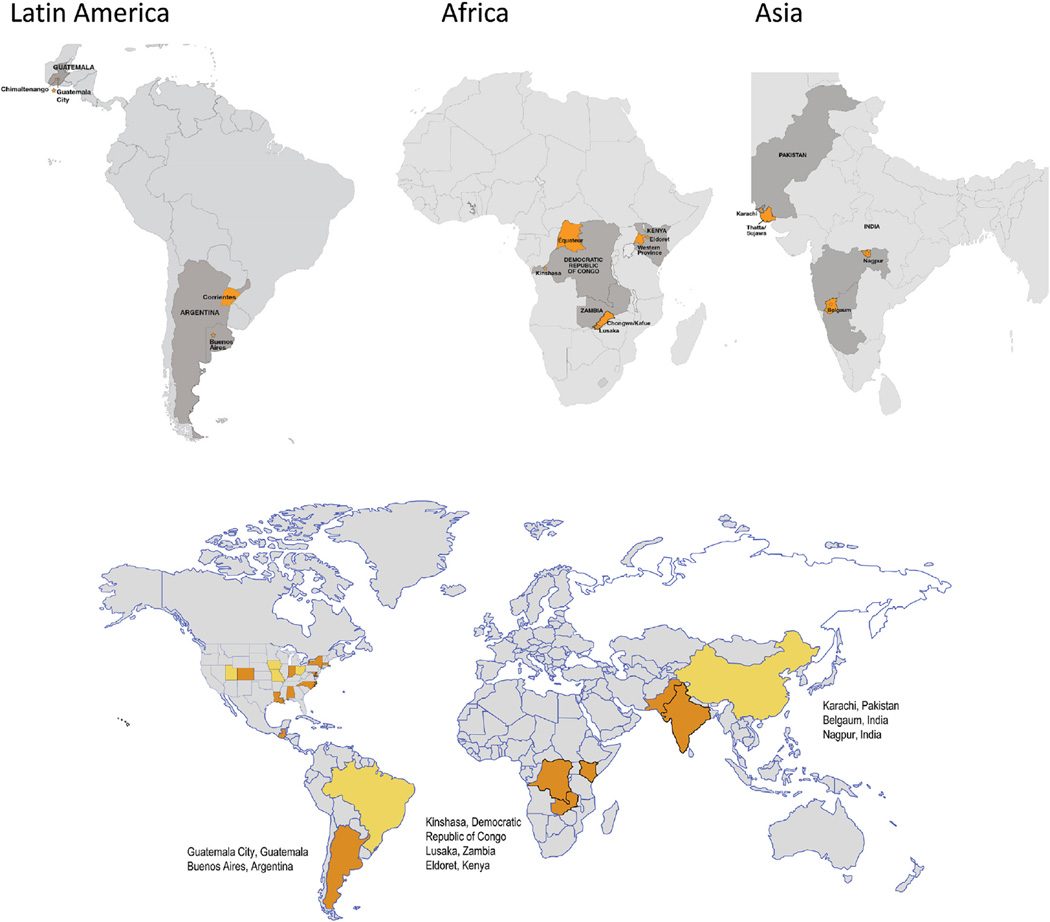

The Global Network currently comprises seven Research Units (RUs) composed of multidisciplinary teams of collaborating US scientists linked to investigators and their institutions in low income countries as full and equal partners; an independently funded single DCC) which provides research support services and methodological and statistical expertise; and the NIH (represented by the NICHD Project Scientist and Program Official) (Table 2). The current sites include India (Belgaum and Nagpur), Pakistan, Guatemala, Zambia, Kenya, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (Fig. 1). Former member sites were located in Argentina, Uruguay, Tibet, and Brazil. The administrative and funding instrument used for this program is the cooperative agreement (NIH U10), an “assistance” mechanism (rather than an “acquisition” mechanism), in which substantial NIH programmatic involvement with the awardees is anticipated during the performance of the activities. Under the cooperative agreement, the NIH purpose is to support and stimulate the recipients' activities by involvement in, and otherwise working jointly with, the award recipients in a partnership role; it is not to assume direction, prime responsibility, or a dominant role in the activities. Global Network grantees are selected based on NIH review of meritorious applications which are submitted in response to a request for applications. Applicants, who must represent sites from low income countries, are graded based on the scientific rigor of their application as well as the ability to demonstrate scientific productivity, access to the relevant populations of interest, in-country organizational capability, a history of collaboration, evidence of foreign institution support, appropriate multidisciplinary expertise, and sensitivity to the ethical and cultural issues related to global health research.

Table 2.

Study investigators, 2011–2015.

| Study Site | Senior foreign investigator | US principal investigator |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | Jose Belizan | Pierre Buekens |

| DRC | Antoinette Tshefu | Carl Bose |

| Zambia | Elwyn Chomba | Waldemar Carlo |

| Guatemala | Ana Garces | Nancy Krebs, Michael Hambidge |

| Belgaum, India | Bhala Kodkany | Richard Derman |

| Pakistan | Omrana Pasha | Robert Goldenberg |

| Nagpur, India | Archana Patel | Pat Hibberd |

| Kenya | Fabian Esamai | Edward Liechty |

| Data Coordinating Center | – | Elizabeth McClure |

Fig. 1.

Map of Global Network sites. DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo.

4. Leaders in global health research

With more than 102 research clusters in six countries around the world and seven highly experienced RUs with a cadre of academic, clinical, epidemiologic professionals working in collaboration with universities, health organizations and ministries of health, the Global Network is unique in its role in promoting the health and well-being of mothers and their children in the settings where it operates [25–32]. The collaborative nature of the program and the outcomes of the research have led to discovery of evidence-based scientific knowledge with implications for practice and policy. Our activities have resulted in substantial expansion of the skills of local health workers and physicians and have afforded opportunities to local scientists to develop protocols, abstracts, manuscripts, and presentations. Local capabilities in information technology and data collection and management have also been augmented; these activities are designed to facilitate independent continuation of local research activities that will ultimately lead to improved health care systems in the participating countries.

5. Landmark trials

The Global Network has conducted a number of individual site and multi-site trials that have outcomes which have been influential in developing both the global research agenda and policy. Several of these are described below and summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Global Network: randomized clinical trials.

| Clinical trial | Main findings |

|---|---|

| Misoprostol to reduce postpartum hemorrhage [4] | Oral misoprostol was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of acute postpartum hemorrhage and acute severe postpartum hemorrhage. One case of postpartum hemorrhage was prevented for every 18 women treated. Postpartum hemorrhage rates fell over time in both groups but remained significantly higher in the placebo group. |

| First Breath: community-based training and intervention in neonatal resuscitation [14] | With community-based training in neonatal resuscitation, there was no significant reduction in the neonatal death rate from all causes or perinatal death in the intervention clusters; however, there was a significant reduction in the rate of stillbirth resulting in an overall decrease in the perinatal mortality rates among intervention clusters. |

| First Bites: Global Network Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of complementary feeding to improve linear growth [46] | Linear growth rates did not differ between the treatment groups. The high rate of stunting at baseline and the lack of effect of either the meat or multiple micronutrient-fortified cereal intervention to reverse its progression argue for multifaceted interventions beginning in the pre- and early postnatal periods. |

| EMONC: a combined community- and facility-based approach to improve pregnancy outcomes in low-resource settings [15] | This community-based intervention did not significantly reduce perinatal mortality in community settings. |

| ACT: Antenatal Corticosteroids Trial to reduce neonatal mortality associated with preterm birth [18] | Despite increased use of antenatal corticosteroids in low-birthweight infants in the intervention groups, neonatal mortality did not decrease in this group, and increased in the population overall. For every 1000 women exposed to this strategy, an excess of 3.5 neonatal deaths occurred, and the risk of maternal infection seems to have been increased. |

| Maternal Newborn Health Registry (MNHR) [23] | The MNHR has enrolled >450,000 pregnant women with 97% follow-up to delivery and six weeks postpartum. |

5.1. Misoprostol

In a placebo-controlled trial undertaken between September, 2002, and December, 2005, 1620 women in rural India were randomized to receive oral misoprostol (n = 812) or placebo (n = 808) after delivery [4]. Auxiliary nurse midwives undertook the deliveries, administered the study drug, and measured blood loss. The primary outcome was the incidence of acute postpartum hemorrhage (defined as ≥500 mL bleeding) within 2 h of delivery. Analysis was by intention-to-treat. Oral misoprostol was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of acute postpartum hemorrhage {from 12.0% to 6.4%; P < 0.0001; relative risk: 0.53 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.39–0.74]} and acute severe postpartum hemorrhage [from 1.2% to 0.2%; P < 0.0001; 0.20 (0.04–0.91)]. One case of postpartum hemorrhage was prevented for every 18 women treated. Misoprostol was also associated with a decrease in mean postpartum blood loss (from 262.3 to 214.3 mL, P < 0.0001). Postpartum hemorrhage rates fell over time in both groups but remained significantly higher in the placebo group. Based on this preliminary work, oral misoprostol was added to the World Health Organization (WHO) essential drug list in June 2012 [32].

5.2. Newborn care training in developing countries (First Breath)

The First Breath Trial used a train-the-trainer model: local instructors trained birth attendants from rural communities in six countries (Argentina, Democratic Republic of Congo, Guatemala, India, Pakistan, and Zambia) in the WHO Essential Newborn Care course (ENC) which focuses on routine neonatal care, resuscitation, thermoregulation, breastfeeding, “kangaroo” [skin-to-skin] care, care of the small baby, and common illnesses and (except in Argentina) in a modified version of the American Academy of Pediatrics Neonatal Resuscitation Program (basic resuscitation skills). The ENC intervention was assessed among 57,643 infants with a pre–post design and then clusters were randomized to NRP training or standard care. The primary outcome was neonatal death in the first seven days after birth. Although there was no significant reduction in the neonatal death rate from all causes or perinatal death in the intervention clusters, there was a significant reduction in the rate of stillbirth (relative risk with training: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.54–0.88; P = 0.003) [14]. The Helping Babies Breathe (HBB) initiative originated as a development from the Global Network First Breath trial. HBB was field-tested and has been scaled up globally by the American Academy of Pediatrics, USAID and its partners, Saving Newborn Lives, Laerdal, Inc. in consultation with the Global Network [33]. Subsequently, the Global Network undertook a pre–post study to evaluate the impact of the HBB training program on all-cause mortality [19].

5.3. Maternal Newborn Health Registry

The Global Network's Maternal Newborn Health Registry (MNHR) is a prospective, population-based registry of pregnancies at the Global Network sites [23]. It began in May 2008, as an expansion of the population-based data collection tool established at Global Network sites for the First Breath Study. The primary purpose of the MNHR is to quantify and analyze trends in pregnancy outcomes over time in order to provide population-level statistics within defined geographic areas [24,27,34,35]. In addition, the MNHR provides data to plan future studies in the Global Network and continues to serve as a data collection tool for pregnancy outcomes in individual studies. To date, more than 450,000 pregnant women have been enrolled, of which delivery outcome data have been reported for 98.9% of women enrolled and 98% of 42 day follow-up visits, overall. No site has had >5% loss to follow-up at 42 days postpartum [36]. Each site develops a monitoring plan to ensure the quality of the data through assessment of various indicators of completeness of data collection, data quality, data accuracy and data entry. The data are collected by registry administrators who train on the completion of data forms, schedule of data collection and process for editing data forms. Birth attendants are trained to collect data and assess basic clinical variables and outcomes, including differentiation of stillbirths from early neonatal deaths, birth weight and assessment of gestational age. This is the only database of pregnancy and pregnancy-related birth outcomes of such magnitude in low-resource settings.

5.4. Antenatal corticosteroids trial (ACT)

From 2011 to 2014, the Global Network conducted a randomized controlled trial with a focus on reduction of neonatal mortality by improving the identification of women at high risk of preterm delivery [18]. The four components of the intervention included: (1) diffusing recommendations to health care providers for appropriate antenatal corticosteroid (ACS) use; (2) training healthcare providers to identify the signs of preterm labor and eligibility criteria for ACS use among pregnant women; (3) providing reminders to health care providers on the use of the kits; (4) using a color-coded tape to measure uterine height in order to estimate gestational age in women at risk for preterm delivery with unknown gestational age. Because gestational age dating was challenging in these settings, <5th percentile birth weight was used as a proxy for preterm birth. The primary findings showed that the intervention effectively increased ACS administration in <5th percentile infants (45% vs 10%) – there was overtreatment of ACS (12% of all women received ACS; 16% of them delivered <5th percentile). Neonatal mortality rates did not decrease in small infants or in preterm births. Among all births, the intervention resulted in a 3.5 per 1000 absolute increase in neonatal deaths and a 5.1 per 1000 increase in perinatal deaths. The negative impact on stillbirths was also significant. The negative effect was concentrated among infants >25th percentile birth weight. There was a 3.6% absolute increase in suspected infection among mothers of small babies and 0.8% among all women. Since the results were published in The Lancet they have generated extensive interest regarding the current practice and guidelines around the use of ACS in community settings [37,38].

6. Capacity building

In more than a decade of its existence the Global Network has developed a strong cadre of interdisciplinary health research teams both at the US institutions and in the foreign sites. For each clinical trial conducted, there has a combination of health workers in the field using train-the-trainer models (Table 4). Training in health interventions has included neonatal resuscitation, birth attendant training in active management of third stage of labor, accurate data collection and reporting by the pregnancy and birth registry administrators, assessment of gestational age in pregnancy using tools and materials developed and validated by investigators [39], use of Doptone for fetal heart detection, care and feeding of the low birth weight/preterm infant [40], use of ultrasound to detect pregnancy complications [41], verbal autopsy to verify cause of death [21], and sample collections for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics analyses [11]. By virtue of their participation in the Global Network, principal investigators, senior foreign investigators and team members alike have received numerous academic awards and recognition from their home institutions and the health systems of their countries. Specifically, 26 Global Network-affiliated investigators have completed Masters degrees, nine PhDs or other doctorate degrees, and during the Global Network tenure at least 20 promotions and 18 various awards spanning national and international organizations, universities and societies such as the American Pediatric Society, Asian Society of Pediatric Research, Early Career Award from the Thrasher Fund, the International Development Research Centre (Canada) and the American Academy of Pediatrics Apgar award have been obtained. Many of these are credited to the research activities performed with the Global Network. In addition, each team has contributed to the scientific community, through presentations at conferences and publications, with more than 100 publications generated from the Global Network, the majority of which have originated from the international scientists, and 32 different international investigators leading a publication.

Table 4.

Health and research training conducted within Global Network for multi-site research.

| Type of training | Trainees | Study |

|---|---|---|

| Essential newborn care (ENC) | Traditional birth attendants (TBAs), nurses, midwives, physicians | First Breath |

| Neonatal resuscitation | Traditional birth attendants (TBAs), nurses, midwives, physicians | First Breath |

| Cause of stillbirth and early neonatal death | Nurse, midwives, community health workers | Verbal autopsy |

| Early intervention program | Community health workers, nurses | BRAIN |

| Home-based life-savings skills | TBAs, community health workers, nurses | Emergency Obstetric Maternal and Neonatal Care (EMONC) trial |

| Community mobilization skills | Community health workers, traditional birth attendants | EMONC trial |

| Emergency obstetric and newborn care | Physicians, nurses | EMONC trial |

| Gestational age assessment | Physicians, nurses, community health workers | Antenatal Corticosteroid Trial |

| Preterm birth assessment | Physicians, nurses, community health workers | Antenatal Corticosteroid Trial |

| Newborn resuscitation | Physicians, nurses, midwives, community health workers | Helping babies breathe |

| Anthropometric measurements | Health visitors | Women First: Preconception Nutrition |

| Basic obstetric ultrasound | Nurses, midwives | First Look: Ultrasound at Antenatal Care |

7. Discussion

In a recent review of the impact of reducing preventable deaths [42] the authors predict that the maximum effect on neonatal deaths is through interventions delivered during labor and child birth, including for obstetric complications (41%), followed by care of small and ill newborn babies (30%). They further go on to report that meeting the unmet need for family planning with modern contraceptives would be synergistic, and would contribute to around a halving of births and therefore deaths. Their analysis also indicates that available interventions can reduce the three most common causes of neonatal mortality – preterm, intrapartum, and infection-related deaths – by 58%, 79%, and 84%, respectively. In 2009, Bhutta et al. conducted a meta-analysis of published research to derive the evidence for community and health systems approaches to improve uptake and quality of antenatal and intrapartum care, and synthesize program and policy recommendations for how best to deliver evidence-based interventions at community and facility levels, across the continuum of care, to reduce stillbirths [43]. Their recommendation was for the implementation of packages of interventions to be tailored to local conditions, including local levels and causes of stillbirth, accessibility of care and health system resources and provider skill. This approach, featuring a package of interventions, is precisely what the Global Network has embarked upon.

In the second funding cycle, the Global Network developed an informal five-year strategic plan which encompassed addressing the spectrum of health-related issues that had the highest morbidity and mortality among the study population. After the successful misoprostol trial that showed a significant reduction in postpartum hemorrhage with community-based use of misoprostol, the goal of subsequent trials was to reduce early neonatal mortality (FB), improve the accuracy of tracking and reporting pregnancy and pregnancy-related outcomes (MNHR), facilitate access to care and enhance referrals systems for pregnant women during labor and delivery (EmONC), improve survival of at-risk preterm infants (ACT) and enhance growth and survival by encouraging exclusive breastfeeding and improving complementary feeding up to age two years. Both the positive and negative outcomes of the trials have been instrumental in driving the international research agenda and health care practice in low resource settings.

Undeniable challenges to the research include issues related to data reporting such as misclassification of cause of death, for which the investigators are now validating a new cause of death tool to improve accuracy and consistency in assignment by the MNHR staff [44]. The lack of robust civil registration systems in the Global Network clusters poses a problem for comparability of ascertainment of all pregnancies and the outcomes. An internal monitoring process has been developed in order to track performance as a measure of quality. Given the diverse nature of the Global Network clusters, each site models its tracking system around the current health system structure taking into account cultural beliefs and practices surrounding pregnancy and child birth. Performance benchmarks were created and sites with low recruitment were successful in improving performance through creative means such as giving cell phones and scales to village elders (Kenya) and developing an eligible-woman-tracking system among newlyweds (Belgaum) [45,46]. Close relationships between the registry administrators and birth attendants in the communities has enhanced reporting of events such as pregnancy loss or stillbirths, which were previously under-reported. Building trust within the communities has helped facilitate the 98% rate of outcomes captured, on a consistent basis since 2010. Though not formally studied, contextual factors such as free health care provision, environmental disasters such as floods, and sudden changes in personnel are implicated in the data-reporting trends that are seen. Keen understanding and appreciation for these issues by investigators within the Global Network allow for corrective action and adjustments to reduce bias in the interpretation of the results.

8. Conclusion

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD's Global Network for Women's and Children's Health Research is one of more than 70 NICHD networks, consortia and centers that are funded to conduct a broad range of research with areas of interest that include AIDS and HIV, disability among children, obstetric–fetal pharmacology, reproductive medicine and rare diseases, to name a few. Though the Global Network has not directly funded training of fellows or other graduate degrees, such as the Fogarty International Center, all research staff participate in and receive accreditation in Good Clinical Practice as well as additional research training and clinical intervention training.

For every trial conducted, particularly for the common protocols, development of the study relies on the potential for capacity building as one of the major criteria that the Steering Committee uses to score the concept. When a trial is approved for implementation in the field, part of the preparation is identification of research staff who will need to be trained in the various areas of study implementation, enrollment and consent, data entry and management.

The assessment and retention of skills among the health workers has been evaluated for several studies. Some skill-sets are more reliably replicated than others; however, the capacity of the research teams clearly has grown overall. Ultimately, the continued involvement of a relatively stable number of clusters for such an extended time has been effective, as demonstrated by the ability to conduct large multi-site, multi-country randomized clinical trials with rigor.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

This study was funded by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U01 HD040477; U01 HD043464; U01 HD040657; U01 HD042372; U01 HD040607; U01 HD058322; U01 HD058326; U01 HD040636; U01 HD043475).

Appendix. Global Network Investigators

Argentina: José M. Belizán, Fernando Althabe (Institute for Clinical Effectiveness and Health Policy), Pierre M. Buekens (Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine); Democratic Republic of Congo: Antoinette Tshefu (Kinshasa School of Public Health), Carl L. Bose (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill); Guatemala: Ana Garces (Francisco Marroquin University), K. Michael Hambidge and Nancy F. Krebs (University of Colorado); India (Belgaum): Bhalchandra S. Kodkany, Shivaprasad S. Goudar (KLE University's Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College), Richard J. Derman (Christiana Healthcare, Delaware); India (Nagpur): Archana Patel (Indira Gandhi Government Medical College; Latta Medical Research Foundation), Patricia L. Hibberd (Massachusetts General Hospital); Kenya: Fabian Esamai (Moi University School of Medicine), Edward A. Liechty (Indiana University); Pakistan: Omrana Pasha (Aga Khan University), Sarah Saleem (Aga Khan University), Robert L. Goldenberg (Columbia University); Zambia: Elwyn Chomba (University of Zambia), Waldemar A. Carlo (University of Alabama at Birmingham); Data Coordinating Center: Elizabeth M. McClure, Dennis D. Wallace (RTI International); Global Network Chair: Alan H. Jobe (Cincinnati Children's Hospital); Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development: Marion Koso-Thomas, Menachem Miodovnik.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Oestergaard MZ, Inoue M, Yoshida S, Mahanani WR, Gore FM, Cousens S, et al. United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation and the Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group. Neonatal mortality levels for 193 countries in 2009 with trends since 1990: a systematic analysis of progress, projections, and priorities. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cousens S, Blencowe H, Stanton C, Chou D, Ahmed S, Steinhardt L, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2009 with trends since 1995: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1319–1330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhutta ZA, Black RE. Global maternal, newborn, and child health. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1073. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1316332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derman RJ, Kodkany BS, Goudar SS, Geller SE, Naik VA, Bellad MB, et al. Oral misoprostol in preventing postpartum haemorrhage in resource-poor communities: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1248–1253. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jehan I, Harris H, Salat S, Zeb A, Mobeen N, Pasha O, et al. Neonatal mortality, risk factors and causes: a prospective population-based cohort study in urban Pakistan. Bull WHO. 2009;87:130–138. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.050963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chomba E, McClure EM, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Chakraborty H, Harris H. Effect of WHO newborn care training on neonatal mortality by education. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8:300–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spinnato JA, 2nd, Freire S, Pinto e Silva JL, Rudge MV, Martins-Costa S, Koch MA, et al. Antioxidant therapy to prevent preeclampsia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1311–1318. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000289576.43441.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller S, Tudor C, Thorsten V, Nyima, Kalyang, Sonam, et al. Randomized double masked trial of Zhi Byed 11, a Tibetan traditional medicine, versus misoprostol to prevent postpartum hemorrhage in Lhasa, Tibet. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2009;54:133–141. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wehby GL, Goco N, Moretti-Ferreira D, Felix T, Richieri-Costa A, Padovani C, et al. Oral cleft prevention program (OCPP) BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:184. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Althabe F, Buekens P, Bergel E, Belizán JM, Campbell MK, Moss N, et al. Guidelines Trial Group. A behavioral intervention to improve obstetrical care. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1929–1940. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa071456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onyamboko MA, Meshnick SR, Fleckenstein L, Koch MA, Atibu J, Lokomba V, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of artesunate and dihydroartemisinin following oral treatment in pregnant women with asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum infections in Kinshasa DRC. Malar J. 2011;10:49. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazariegos M, Hambidge KM, Westcott JE, Solomons NW, Raboy V, Das A, et al. Neither a zinc supplement nor phytate-reduced maize nor their combination enhance growth of 6- to 12-month-old Guatemalan infants. J Nutr. 2010;140:1041–1048. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.115154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krebs NF, Hambidge KM, Mazariegos M, Westcott J, Goco N, Wright LL, et al. Complementary Feeding Study Group. Complementary feeding: a Global Network cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-11-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlo WA, Goudar SS, Jehan I, Chomba E, Tshefu A, Garces A, et al. First Breath Study Group. Newborn-care training and perinatal mortality in developing countries. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:614–623. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasha O, Goldenberg RL, McClure EM, Saleem S, Goudar SS, Althabe F, et al. Communities, birth attendants and health facilities: a continuum of emergency maternal and newborn care (the Global Network’s EmONC trial) BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClure EM, Pasha O, Goudar SS, Chomba E, Garces A, Tshefu A, et al. NICHD First Breath Study Group. The global network: a prospective study of stillbirths in developing countries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:247, e1–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Althabe F, Belizán JM, Mazzoni A, Berrueta M, Hemingway-Foday J, Koso-Thomas M, et al. Antenatal corticosteroids trial in preterm births to increase neonatal survival in developing countries: study protocol. Reprod Health. 2012;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Althabe F, Belizán JM, McClure EM, Hemingway-Foday J, Berrueta M, Mazzoni A, et al. A population-based, multifaceted strategy to implement antenatal corticosteroid treatment versus standard care for the reduction of neonatal mortality due to preterm birth in low-income and middle-income countries: the ACT cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9968):629–639. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61651-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bang A, Bellad R, Gisore P, Hibberd P, Patel A, Goudar S, et al. Implementation and evaluation of the Helping Babies Breathe curriculum in three resource limited settings: does Helping Babies Breathe save lives? A study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hambidge KM, Krebs NF, Westcott JE, Garces A, Goudar SS, Kodkany BS, et al. Preconception Trial Group. Preconception maternal nutrition: a multi-site randomized controlled trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engmann C, Garces A, Jehan I, Ditekemena J, Phiri M, Thorsten V, et al. Birth attendants as perinatal verbal autopsy respondents in low- and middle-income countries: a viable alternative? Bull WHO. 2012;90:200–208. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.092452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carlo WA, Goudar SS, Pasha O, Chomba E, Wallander JL, Biasini FJ, et al. Brain Research to Ameliorate Impaired Neurodevelopment-Home-based Intervention Trial Committee; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants requiring resuscitation in developing countries. J Pediatr. 2012;160:781–785. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goudar SS, Carlo WA, McClure EM, Pasha O, Patel A, Esamai F, et al. The Maternal and Newborn Health Registry Study of the Global Network for Women’s and Children’s Health Research. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;118:190–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saleem S, McClure EM, Goudar SS, Patel A, Esamai F, Garces A, et al. Global Network Maternal Newborn Health Registry Study Investigators. A prospective study of maternal, fetal and neonatal deaths in low- and middle-income countries. Bull WHO. 2014;92:605–612. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.127464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kodkany BS, Derman RJ. Evidence-based interventions to prevent postpartum hemorrhage: translating research into practice. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;94(Suppl 2):S114–S115. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biasini FJ, De Jong D, Ryan S, Thorsten V, Bann C, Bellad R, et al. Development of a 12 month screener based on items from the Bayley II Scales of Infant Development for use in Low Middle Income countries. Early Hum Dev. 2015;91:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belizán JM, McClure EM, Goudar SS, Pasha O, Esamai F, Patel A, et al. Neonatal death in low- to middle-income countries: a global network study. Am J Perinatol. 2012;29:649–656. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1314885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hambidge KM, Sheng X, Mazariegos M, Jiang T, Garces A, Li D, et al. Evaluation of meat as a first complementary food for breastfed infants: impact on iron intake. Nutr Rev. 2011;69(Suppl 1):S57–S63. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manasyan A, Saleem S, Koso-Thomas M, Althabe F, Pasha O, Chomba E, et al. EmONC Trial Group. Assessment of obstetric and neonatal health services in developing country health facilities. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:787–794. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1333409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldenberg RL, McClure EM, Saleem S. A review of studies with chlorhexidine applied directly to the umbilical cord. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:699–701. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1329695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garces A, McClure EM, Chomba E, Patel A, Pasha O, Tshefu A, et al. Home birth attendants in low income countries: who are they and what do they do? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. Available at: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/index.html.

- 33.Ersdal HL, Singhal N. Resuscitation in resource-limited settings. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;18:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marete I, Tenge C, Pasha O, Goudar S, Chomba E, Patel A, et al. Perinatal outcomes of multiple-gestation pregnancies in Kenya, Zambia, Pakistan, India, Guatemala, and Argentina: a global network study. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31:125–132. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1338173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McClure EM, Pasha O, Goudar SS, Chomba E, Garces A, Tshefu A, et al. Global Network Investigators. Epidemiology of stillbirth in low–middle income countries: a Global Network Study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:1379–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goudar SS, Stolka KB, Koso-Thomas M, McClure EM, Carlo WA, Goldenberg RL, et al. The Global Network’s Maternal Newborn Health Registry: data quality monitoring and performance metrics. Reprod Health. 2015;12(Suppl 2):S2. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hodgins S. Caution on corticosteroids for preterm delivery: learning from missteps. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2014;2:371–373. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Althabe F, Berrueta M, Hemingway-Foday J, Mazzoni A, Bonorino CA, Gowdak A, et al. Tape to assess fundal height: a Global Network study. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0117134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldenberg RL, McClure EM, Kodkany B, Wembodinga G, Pasha O, Esamai F, et al. A multi-country study of the “intrapartum stillbirth and early neonatal death indicator” in hospitals in low-resource settings. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122:230–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McClure EM, Nathan RO, Saleem S, Esamai F, Garces A, Chomba E, et al. First look: a cluster-randomized trial of ultrasound to improve pregnancy outcomes in low income country settings. BMC Pregn Childbirth. 2014;14:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R, Lawn JE, Salam RA, Paul VK, et al. Lancet Newborn Interventions Review Group; Lancet Every Newborn Study Group. Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet. 2014;384(9940):347–370. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60792-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Haws RA, Yakoob MY, Lawn JE. Delivering interventions to reduce the global burden of stillbirths: improving service supply and community demand. BMC Pregn Childbirth. 2009;9(Suppl 1):S7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-S1-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McClure EM, Bose CL, Garces A, Esamai F, Goudar SS, Patel A, et al. Global network for women’s and children’s health research: a system for low-resource areas to determine probable causes of stillbirth, neonatal, and maternal death. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2015;1:11. doi: 10.1186/s40748-015-0012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gisore P, Rono B, Marete I, Nekesa-Mangeni J, Tenge C, Shipala E, et al. Commonly cited incentives in the community implementation of the emergency maternal and newborn care study in western Kenya. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13:461–468. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v13i2.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kodkany B, Derman RJ, Honnungar N, Tyagi N, Goudar SS, Mastiholi S, et al. Establishment of a Maternal Newborn Health Registry in the Belgaum District of Karnataka, India. Reprod Health. 2015;12(Suppl 2):S3. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-12-S2-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krebs NF, Mazariegos M, Chomba E, Sami N, Pasha O, Tshefu A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of meat compared with multimicronutrient-fortified cereal in infants and toddlers with high stunting rates in diverse settings. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:840–847. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.041962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]