Abstract

Patient: Female, 70

Final Diagnosis: Malignant mesothelioma

Symptoms: —

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Radiation/Chemotherapy

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Rare co-existance of disease or pathology

Background:

The histopathological diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma is based mainly on the immunohistological profile of the neoplasia, using different immunohistochemical markers to distinguish between a malignant mesothelioma and a carcinoma.

Case Report:

A female patient presented with a right paravertebral rapidly growing tumor and severe pain. Based on the immunohistochemical findings, we present the first case of a malignant mesothelioma with immunohistochemical expression of thyroid transcription factor-1.

Conclusions:

The detection of a positive reaction for thyroid transcription factor-1 in the tumor cells may not exclude a malignant mesothelioma.

MeSH Keywords: Diagnosis, Differential; Mesothelioma; Pathology, Surgical; Pleural Diseases

Background

Malignant mesothelioma is a rare malignant disease, but its incidence is increasing worldwide, strongly associated with amphibole asbestos exposure [1–3]. It is thought that the parietal pleura are the basis for malignant mesothelioma; however, there are rare cases of primary peritoneal mesothelioma [4–6]. The localized malignant mesothelioma is a very rare tumor that grossly appears as a distinctly localized nodular lesion without gross or microscopic evidence of diffuse pleural spread. There are many immunohistochemical markers known to distinguish between a malignant mesothelioma and a carcinoma, including pancytokeratin, cytokeratin 5/6, calretinin, WT-1, D2-40, BG8, MOC-31, EpCAM (BerEP4), Claudin, and TTF-1 [7–10]. The expression of thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) is positive in about 85% of lung adenocarcinoma and in thyroid carcinoma cases. Other tumors rarely show TTF-1 expression; for example, 10% of colorectal cancers show this expression, but so far none have been described in malignant mesothelioma [10].

Case Report

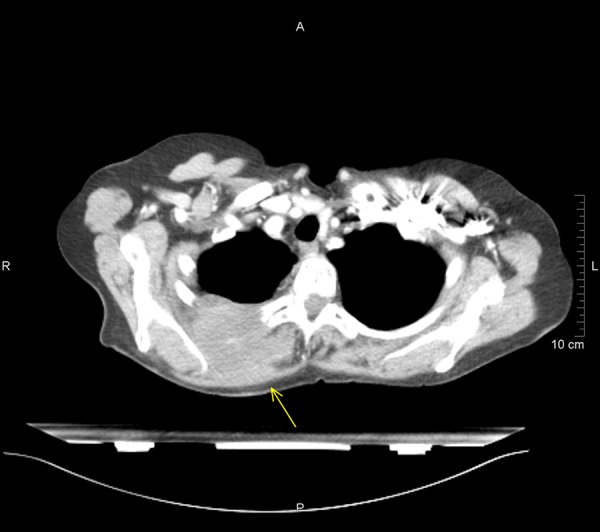

A 70-year-old white female presented with a right paravertebral rapidly (within 4 weeks) growing tumor and severe pain, for which morphine was administered. Since 2003, the patient had been under observation because of stable B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL), Rai staging 0, and slowly advancing Alzheimer disease. A cerebral metastasis had been excluded by computerized tomography (CT). The patient was employed as a commercial clerk without particular work-related exposure to noxa, such as asbestos or radiation. In the clinical examination, an approximately 4-cm lesion expansion, painful when pressed, was found in the area of the upper third paravertebral right of the thoracic spine. Further tumor manifestations were excluded clinically and by CT. The CT showed a 6×5 cm large lesion expansion with the beginning of shallow erosion of the 4th rib dorsal right. The lesion expansion extended continuously from the pleura (there was a pleura swelling approximately 1.5 cm large and 4.0 cm long) through the thorax wall in between the ribs to the margo lateralis scapulae (Figure 1). A vicinal triangular subpleural atelectasis and smaller pleural effusion were secondary findings.

Figure 1.

Axial CT scan showing an expansive lesion with the beginning of shallow erosion of the 4. rib dorsal right.

Using a rechargeable pistol from Barth with insertable Trucut needles (14G), tissue cylinders from the lesion expansion were obtained for histological assessment. The sonography-guided puncture under sterile conditions is preferable, because with a one-person one-hand puncture necessary corrections can be performed quickly.

The specimens were routinely fixated in 4% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 3–4 µm thick sections. Then they were routinely stained with hematoxylin and eosin. They were also immunohistochemically stained with primary antibodies cytokeratin 5/6 (Cell Marque, Cell Marque Corporation, Rocklin, California, USA), cytokeratin 7 (Roche Diagnostics International AG, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), cytokeratin 20 (Roche Diagnostics International AG, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), calretinin (Roche Diagnostics International AG, Rotkreuz, Switzerland), and TTF-1 (Roche Diagnostics International AG, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) using the ultra-view™ universal alkaline phosphatase red detection kit (Roche Diagnostics International AG, Rotkreuz, Switzerland) on a Benchmark XT device (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc). In addition, on-slide positive controls were used.

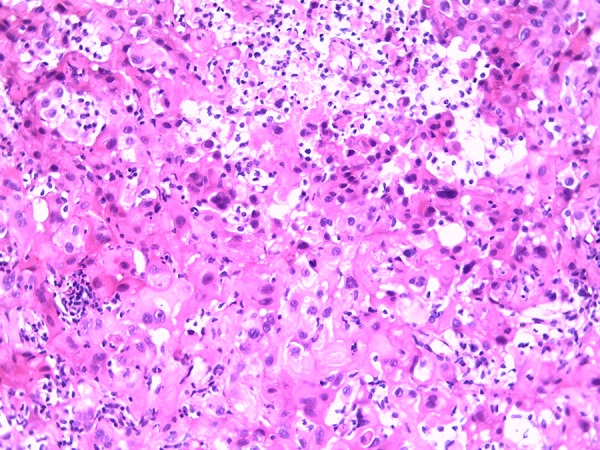

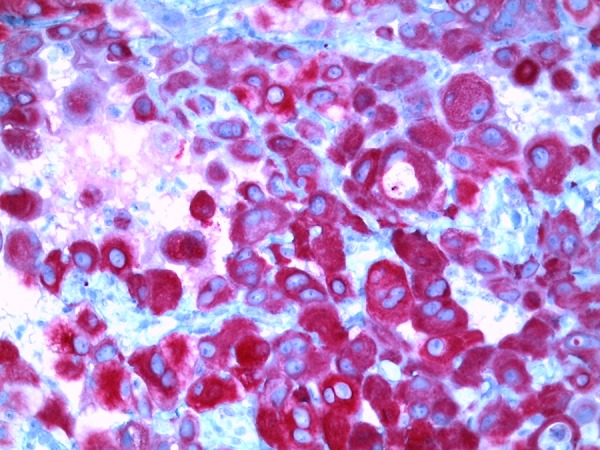

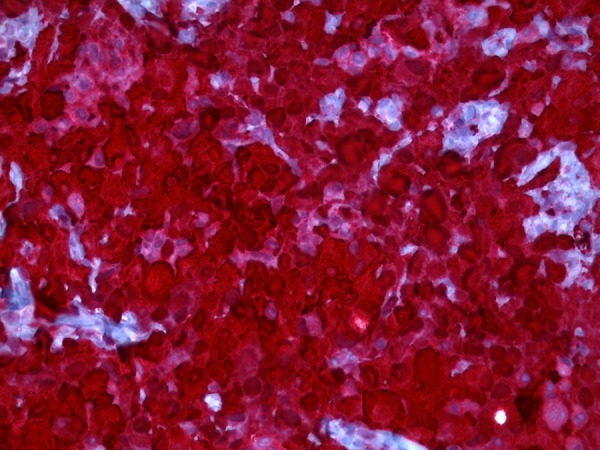

Microscopical examination showed monotonous growth with uniform flat or cuboidal medium-size cells with round nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm [11]. Moreover, mitotic activity and giant cells could be detected. A lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate was verifiable (Figure 2). There was a verifiable negative immunohistochemical reaction in the tumor cells for cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20. A positive reaction was detected in the tumor cells for cytokeratin 5/6 (Figure 3), calretinin (Figure 4), and TTF-1 (Figure 5). In addition, the tumor cells showed an immunohistochemical positive reaction for D2-40 and WT-1 (not shown).

Figure 2.

Micrograph hematoxylin and eosin staining (original magnification ×200).

Figure 3.

Micrograph immunohistochemical positive reaction for cytokeratin 5/6 (original magnification ×400).

Figure 4.

Micrograph immunohistochemical positive reaction for calretinin (original magnification ×400).

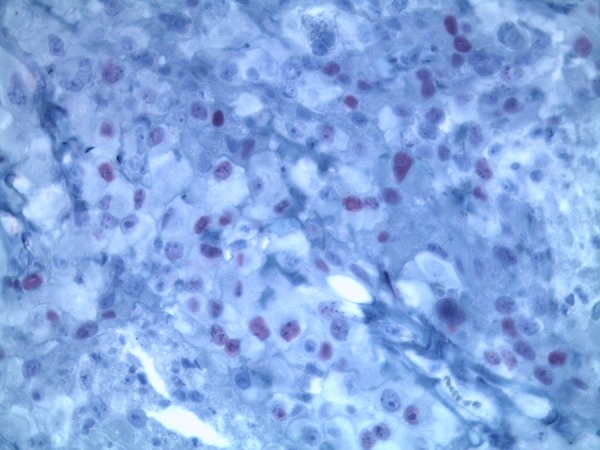

Figure 5.

Micrograph immunohistochemical positive reaction for TTF-1 (original magnification ×400).

The treatment consisted of a combination of radiation/chemotherapy: Cisplatin weekly 20 mg/m2, cumulative dose 240 mg. In addition, the patient was treated in a palliative setting [12,13] with a 6 MV photon beam [14,15] from a linear accelerator. The single dose was 2.5 Gray (Gy), 5 times a week, and the total dose 50.0 Gy. Target volume was the dorsolateral thoracic wall. At the end of this therapy, a sonographically measured 50% tumor reduction was achieved. Four months later, no growth gain was detected. The patient required no analgesic.

Discussion

We present the first report of a malignant mesothelioma with immunohistochemical positive expression of TTF-1. There are many immunohistochemical markers known to distinguish between a malignant mesothelioma and a carcinoma, including pancytokeratin, cytokeratin 5/6, calretinin, WT-1, D2-40, BerEP4, MOC-31, BG8, Claudin, and TTF-1. The expression of TTF-1 is positive in about 85% of lung adenocarcinoma cases and in thyroid carcinoma. Some other tumors rarely show an expression of TTF-1; for example, 10% of colorectal cancers show this expression, but so far none have been described in malignant mesothelioma. TTF-1 is a transcription factor essential for the morphogenesis and differentiation of several organs, including the lungs, ventral forebrain, and thyroid [16]. TTF-1 is necessary for the expression of some genes in the thyroid, lungs, and central nervous system. Human TTF-1 is located on chromosome 14 [17]. In the lungs, TTF-1 controls the expression of surfactant proteins that are essential for lung stability and, until now, TTF-1 was deemed to be negative in mesothelioma [18–20]. We detected a localized malignant mesothelioma with a positive reaction for TTF-1 (Figure 5) in the tumor cells. This was confirmed by the internationally renowned Professor A. Tannapfel, director of the German mesothelioma register of Ruhr University Bochum, who provided scientific consultations. This finding is important for prospective pathological diagnosis of mesothelioma because a positive reaction for TTF-1 may not exclude a malignant mesothelioma.

Conclusions

We present the first report of a malignant mesothelioma with immunohistochemical positive expression of TTF-1. Until now, the detection of TTF-1 seems to have ruled out the diagnosis of a malignant mesothelioma, but now a positive reaction for TTF-1 may no longer exclude a malignant mesothelioma.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient described in this study and the patient’s daughter for her consent for this article. The authors thank Professor Andrea Tannapfel of Ruhr University Bochum, Germany for her support. Also, the authors thank Mrs. Claudia Noble-Pyott for her relentless and excellent work on this case report.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publishing of this paper.

References:

- 1.Wagner JC, Sleggs CA, Marchand P. Diffuse pleural mesothelioma. Br J Ind Med. 1960;17:260–71. doi: 10.1136/oem.17.4.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumann V, Löseke S, Nowak D, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma – incidence, etiology, diagnosis, treatment and occupational health. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:319–26. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sezer A, Sümbül AT, Abalı H, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: A single-center experience in Turkey. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:825–3. doi: 10.12659/MSM.890020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frontario SC, Loveitt A, Goldenberg-Sandau A, et al. Primary peritonael mesothelioma resulting in small bowel obstruction: A case report and review of literature. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:496–500. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.894180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tentes AA, Zorbas G, Pallas N, Fiska A. Multicystic peritonael mesothelioma. Am J Case Rep. 2012;13:262–64. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.883523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellapparadja P, Madhavan P, Slater S. Malignant pleural mesothelioma with spinal fracture – a case report. Am J Case Rep. 2008;9:408–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Husain AN, Colby TV, Ordnez NG, et al. Guidelines for pathologic diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1317–31. doi: 10.5858/133.8.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tischoff I, Tannapfel A. Pathologic and anatomic evidence of peritonael metastases. Chirurg. 2007;78:1085–86. 1088–90. doi: 10.1007/s00104-007-1427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penman D, Downie I, Roberts F. Positive immunostaining for Thyroid-transcription factor-1 in primary and metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma: a note of caution. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:663–64. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.030064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dongfeng T, Zander DS. Immunohistochemistry for assessment of pulmonary and pleural neoplasms: A review and update. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2008;1:19–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Churg A. Fiber counting and analysis in the diagnosis of asbestos related diseases. Hum Pathol. 1982;13:381–92. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(82)80227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rawluk J, Henß H, Waller CF. Mesotheliome. In: Berger DP, Engelhardt R, Mertelsmann R, editors. Das Rote Buch: Hämatologie und Internistische Onkologie. 5th ed. Heidelberg: ecomed MEDIZIN; 2014. pp. 796–801. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore AJ, Parker RJ, Wiggins J. Malignant mesothelioma. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:34. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-3-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Opitz I. Management of malignant pleural mesothelioma – The European experience. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(Suppl.2):S238–52. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.05.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhalluin X, Scherpereel A. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy for mesothelioma. Rec Res Cancer Res. 2011;189:127–47. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-10862-4_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Felice M, Di Lauro R. Thyroid development and its disorders: Genetics and molecular mechanisms. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:722–46. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kishimoto T, Ozaki S, Kato K, et al. Malignant pleural mesothelioma in parts of Japan in relationship to asbestos exposure. Ind Health. 2004;42:435–39. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.42.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ordonez NG. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of epithelial mesothelioma: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1407–14. doi: 10.5858/2005-129-1407-IDOEMA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ordonez NG. The diagnostic utility of immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy in distinguishing between peritoneal mesothelioma and serous carcinoma: a comparative study. Pathology. 2006;19:34–48. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King JE, Thatcher N, Pickering CA, Hasleton PS. Sensitivity and specificity of immunohistochemical markers used in the diagnosis of epitheloid mesothelioma: A detailed systematic analysis using published data. Histopathol. 2006;48:223–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]