Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine delay discounting in girls and boys with ADHD-Combined type (ADHD-C) relative to typically developing (TD) children on two tasks that differ in the extent to which the rewards and delays were experienced by participants. Children ages 8–12 years with ADHD-C (n = 65; 19 girls) and TD controls (n = 55; 15 girls) completed two delay discounting tasks involving a series of choices between smaller, immediate and larger, delayed rewards. The classic delay discounting task involved choices about money at delays of 1–90 days and only some of the outcomes were actually experienced by the participants. The novel real-time discounting task involved choices about an immediately consumable reward (playing a preferred game) at delays of 25–100 s, all of which were actually experienced by participants. Participants also provided subjective ratings of how much they liked playing the game and waiting to play. Girls with ADHD-C displayed greater delay discounting compared to boys with ADHD-C and TD girls and boys on the real-time discounting task. Diagnostic group differences were not evident on the classic discounting task. In addition, children with ADHD-C reported wanting to play the game more and liking waiting to play the game less than TD children. This novel demonstration of greater delay discounting among girls with ADHD-C on a discounting task in which the rewards are immediately consumable and the delays are experienced in real-time informs our understanding of sex differences and motivational processes in children with ADHD.

Keywords: ADHD, Delay discounting, Temporal discounting, Reward, Motivation, Sex differences, Delay aversion

INTRODUCTION

Impulsive decision-making, reflected in a tendency to prefer smaller, immediate rewards over larger, delayed rewards (Reynolds, 2006; Winstanley, Eagle, & Robbins, 2006) has been emphasized in theories of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) postulating altered sensitivity to reinforcement (see review by Luman, Tripp, & Scheres, 2010). However, the empirical literature is fairly mixed. This may be due, in part, to variability in the paradigms used to assess immediate reward preference in terms of whether the rewards and delays were actually experienced by participants, among other important task parameters. Improving our understanding of impulsive decision-making in ADHD is important for elucidating the etiology of this highly prevalent disorder and for informing the development of effective treatments.

The earliest studies of delay-related impulsive choice in relation to ADHD were conducted by Sonuga-Barke and colleagues using the Choice Delay Task (CDT; Sonuga-Barke, Taylor, Sembi, & Smith, 1992), involving 20 choices between a smaller reward (1 point) after a shorter delay (2 s) or a larger reward (2 points) after a longer delay (30 s). Several investigators have used a version of the CDT to study immediate reward preference among individuals with ADHD compared to typically developing (TD) controls. Many found a stronger preference for immediate reward in ADHD (Antrop et al., 2006; Bitsakou, Psychogiou, Thompson, & Sonuga-Barke, 2009; Coghill, Seth, & Matthews, 2013; Dalen, Sonuga-Barke, Hall, & Remington, 2004; Gupta & Kar, 2009; Marco et al., 2009; Solanto et al., 2001; Wahlstedt, Thorell, & Bohlin, 2009), although some reported no diagnostic group differences (Bidwell, Willcutt, Defries, & Pennington, 2007; Solanto et al., 2007). Interpretation of these findings is confounded, however, by two issues. First, a majority of these studies did not impose a post-reward delay (i.e., a delay after receiving the reward to keep the rate of reinforcement constant), such that choosing the smaller, immediate reward would also end the task more quickly (c.f., Marco et al., 2009; Sonuga-Barke et al., 1992). Second, participants were often told that the goal of the task is to maximize the number of points they earn, although these points are infrequently associated with an actual reward (c.f., Solanto et al., 2001, 2007). These procedural aspects may impact impulsive decision-making if, for example, the participant is more motivated to end the task rather than earn more points or if they are not making valid choices because they do not actually receive the reward.

Temporal or delay discounting tasks have also been used to study impulsive decision-making in ADHD and other disorders associated with poor impulse control (see review by Reynolds, 2006). Delay discounting tasks involve choices between smaller, immediate rewards and larger delayed rewards, similar to the CDT, although the magnitude of the rewards and delays is varied rather than presenting the same choice repeatedly as is done in the CDT. There is also variation among delay discounting tasks regarding whether the delays and rewards are experienced by the individual in “real-time” or hypothetical in nature (see review by Reynolds, 2006; e.g., Shiels et al., 2009). Although research conducted with adults has suggested that real and hypothetical rewards are not discounted differently (e.g., Lagorio & Madden, 2005; Madden, Begotka, Raiff, & Kastern, 2003), whether children discount real and hypothetical rewards to the same degree has not yet been tested in a systematic way.

In the ADHD literature, the majority of studies have used hypothetical rewards with inconsistent results. Several studies have reported greater discounting of hypothetical rewards among individuals with ADHD (Costa Dias et al., 2013; Dai, Harrow, Song, Rucklidge, & Grace, 2013; Demurie, Roeyers, Baeyens, & Sonuga-Barke, 2012, 2013; Hurst, Kepley, McCalla, & Livermore, 2011; Paloyelis, Asherson, Mehta, Faraone, & Kuntsi, 2010; Wilson, Mitchell, Musser, Schmitt, & Nigg, 2011) and a stronger preference for immediate reward, regardless of delay (Barkley, Edwards, Laneri, Fletcher, & Metevia, 2001) whereas other studies have found similar discounting rates among ADHD and control samples (Chantiluke et al., 2014; Crunelle, Veltman, van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen, Booij, & van den Brink, 2013; Rubia, Halari, Christakou, & Taylor, 2009; Wilbertz et al., 2013, 2012). Studies involving real rewards, typically money, delivered in real-time, have shown greater discounting in ADHD (Scheres, Tontsch, Thoeny, & Kaczkurkin, 2010; Schweitzer & Sulzer-Azaroff, 1995) and no significant diagnostic group differences (Scheres et al., 2006). Thus, despite the theoretical emphasis on a strong preference for immediate reward among individuals with ADHD (Luman et al., 2010), the empirical evidence is inconsistent.

Delay discounting tasks in which the delays and rewards are experienced in real-time are thought to be better suited for children, who may have greater difficulty with abstract decision-making than adults. However, the majority of the real-time discounting tasks involve choices about money, which is a secondary reinforcer in that it is not an immediately consumable reward, such as food or drugs, and has limited utility in the moment that it is received. While there have been some studies using immediately consumable rewards such as video game playing (e.g., Millar & Navarick, 1984) and food (e.g., Logue, Forzano, & Ackerman, 1996), which have been shown to elicit more impulsive responding than do monetary-based reinforcers (Forzano & Logue, 1994), these studies were not conducted with clinical populations. Therefore, the question remains as to whether children with ADHD would display greater delay discounting during a task that involves immediately consumable rewards experienced in real-time compared to TD children. The current study builds on the existing literature by examining delay discounting on two tasks that differ in the extent to which the rewards and delays are experienced in real-time. Specifically, participants completed a real-reward classic discounting task in which they were told that some of the choices were real and two rewards were actually delivered at the chosen delays. They also completed a novel, real-time discounting task which involved immediately consumable rewards delivered in real-time before making the next choice.

Beyond task characteristics, there may also be sample characteristics that contribute to delay discounting, such as age, sex, intelligence, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and ADHD symptoms. In the ADHD delay discounting literature, studies have shown that intelligence (IQ) accounts for diagnostic group differences in delay discounting (e.g., Wilson et al., 2011), that younger kids show a stronger preference for immediate reward (Gupta & Kar, 2009), and that greater discounting is associated with greater hyperactive/impulsive symptoms (Scheres & Hamaker, 2010; Scheres, Lee, & Sumiya, 2008) and greater inattention symptoms (Wilson et al., 2011). Sex differences have been examined in the broader delay discounting literature (not specific to ADHD) with inconsistent results. Studies have reported greater self-control among girls during a delay of gratification task (Mischel & Underwood, 1974), greater delay discounting (i.e., poorer self-control) among adult women during a delay discounting task (Reynolds, Ortengren, Richards, & de Wit, 2006), and an absence of sex differences in preference for delayed larger versus immediate smaller rewards (e.g., Mischel & Metzner, 1962; Wilson et al., 2011). The majority of the ADHD delay aversion/ discounting literature has contained samples of primarily, if not exclusively, boys (e.g., Bitsakou et al., 2009; Coghill et al., 2013; Gupta & Kar, 2009; Marco et al., 2009; Solanto et al., 2001) and none of the existing studies have reported sex differences.

Despite the lack of attention paid to ADHD-related sex differences in delay discounting, important sex differences have emerged in terms of prevalence rates, symptom presentation, comorbidities, and functional outcomes (Biederman et al., 2006; Derks, Hudziak, & Boomsma, 2007; Gaub & Carlson, 1997; Hinshaw, Owens, Sami, & Fargeon, 2006; Keltner & Taylor, 2002; Mikami, Hinshaw, Lee, & Mullin, 2008; Rucklidge, 2010). Studies have also reported sex differences in neuropsychological functioning in children with ADHD (Hasson & Fine, 2012; O’Brien, Dowell, Mostofsky, Denckla, & Mahone, 2010; Seymour, Mostofsky, & Rosch, 2015; Wodka et al., 2008), with girls generally showing more deficits in planning and strategy mediated by prefrontal circuits, and boys showing greater impairments in more basic aspects of response control mediated by motor/ premotor circuits. Two recent studies revealed a sexually dimorphic effect of working memory demands (Seymour et al., 2015) and reinforcement (Rosch, Dirlikov, & Mostofsky, 2015) on response control. Specifically, girls with ADHD only displayed impaired response control under conditions of greater working memory demands, whereas response control was impaired among boys with ADHD regardless of working memory demands (Seymour et al., 2015). In addition, reinforcement did not improve response control among girls with ADHD, whereas it did among boys with ADHD (Rosch et al., 2015). Thus, it appears that response to reward and cognitive control may differ among girls and boys with ADHD and this may relate to differences in delay discounting. Given these findings and the lack of ADHD studies examining sex differences in delay discounting as well as the inconsistent findings in the broader delay discounting literature, we intentionally oversampled for girls to determine whether delay discounting differed among girls and boys with ADHD relative to typically developing same-sex peers. In addition, only participants with the combined subtype of ADHD were included in the study to permit examination of sex differences without the possible confound of subtype differences.

Another factor that may influence delay discounting is how unpleasant the subjective experience of waiting is for an individual, as shown in a recent study (Scheres, Tontsch, & Thoeny, 2013) in which individuals who reported having greater difficulty waiting for a particular delay tended to choose the smaller reward, particularly among children with ADHD. Thus, it may be important to consider the subjective experience of waiting when interpreting diagnostic group differences. The current study builds on the existing literature by obtaining subjective ratings of reward desirability and difficulty waiting, building on the previous study by Scheres et al. (2013), and examining associations among subjective ratings and delay discounting.

The specific hypotheses include: (1) children with ADHD-C will show increased delay discounting relative to TD children, particularly on the real-time discounting task; (2) for the subjective ratings, children with ADHD-C will report wanting to play the preferred game more than TD children and liking waiting to play the game less than TD children; and (3) girls and boys with ADHD-C will differ in the extent to which they show delay discounting relative to same-sex TD children. Exploratory analyses were also conducted to examine whether subjective ratings of reward desirability and difficulty waiting and ADHD symptoms were associated with delay discounting.

METHODS

Participants

A total of one hundred twenty 8- to 12-year-old children participated in this study: 65 children with ADHD-C (19 girls) and 55 TD children (15 girls). Participants were primarily recruited through local schools, with additional resources including community-wide advertisement, volunteer organizations, medical institutions, and word of mouth. This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board, and all data were obtained in compliance with their regulations. After complete description of the study to the participants, written informed consent was obtained from a parent/guardian and assent was obtained from the child.

An initial screening was conducted through a telephone interview with a parent. Children with a history of intellectual disability, seizures, traumatic brain injury or other neurological illnesses were excluded from participation. Intellectual ability was assessed using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition (WISC-IV; Wechsler, 2003) and participants with Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ) scores below 80 were excluded. Children were also administered the Word Reading subtest from the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Second Edition (WIAT-II; Wechsler, 2002) to screen for a reading disorder and were excluded for a significant discrepancy between FSIQ and WIAT-II.

Diagnostic status was established through administration of the Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents, Fourth Edition (DICA-IV; Reich, Welner, & Herjanic, 1997). Children meeting criteria for diagnosis of conduct, mood, generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, or obsessive– compulsive disorders on DICA-IV interview were excluded. A comorbid diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) was permitted. Parents and teachers (when available) also completed the Conners’ Parent and Teacher Rating Scales-Revised Long Version or the Conners-3 (CPRS and CTRS; Conners, 2002, 2008) and the ADHD Rating Scale-IV, home and school versions (ADHD-RS; DuPaul, Power, Anastopoulos, & Reid, 1998).

An ADHD diagnosis was established based on the following criteria: (1) t-score of 60 or higher on the ADHD Inattentive or Hyperactive/Impulsive scales on the CPRS or CTRS, when available, or a score of 2 or 3 on at least 6/9 items on the Inattentive or Hyperactivity/Impulsivity scales of the ADHD-RS and (2) an ADHD diagnosis on the DICA-IV. This information was then reviewed and the diagnosis was confirmed by a child neurologist (S.H.M.). Children taking psychotropic medications other than stimulants were excluded from participation and all children taking stimulants were asked to withhold medication the day before and day of testing.

Inclusion in the TD group required scores below clinical cutoffs on the parent and teacher (when available) rating scales (CPRS, CTRS, and ADHD-RS). Control participants could not meet diagnostic criteria for any psychiatric disorder based on DICA-IV nor could they have history of neurological disorder, be taking psychotropic medication or meet criteria for diagnosis of learning disability based on WIAT-II word reading scores being significantly discrepant from FSIQ, and were required to have an FSIQ above 80. Children included in the TD group also could not have an immediate family member diagnosed with ADHD.

Procedures

Classic “Real-Reward” Discounting Task

Participants completed a computer-based delay discounting task involving 91 choices between a varying amount of money now ($0–$10.50 in $0.50 increments) or $10.00 after a varying delay (1, 7, 30, or 90 days) (Wilson et al., 2011). Participants were instructed to indicate whether they preferred the immediate or delayed option using a computer mouse. They were also told that some of the choices were real and they would actually receive the amount of money at the specified delay that they chose for some of the items in the form of gift cards or prizes (two choices semi-randomly selected). This task took 10–15 min to complete.

Novel “Real-Time” Discounting Task

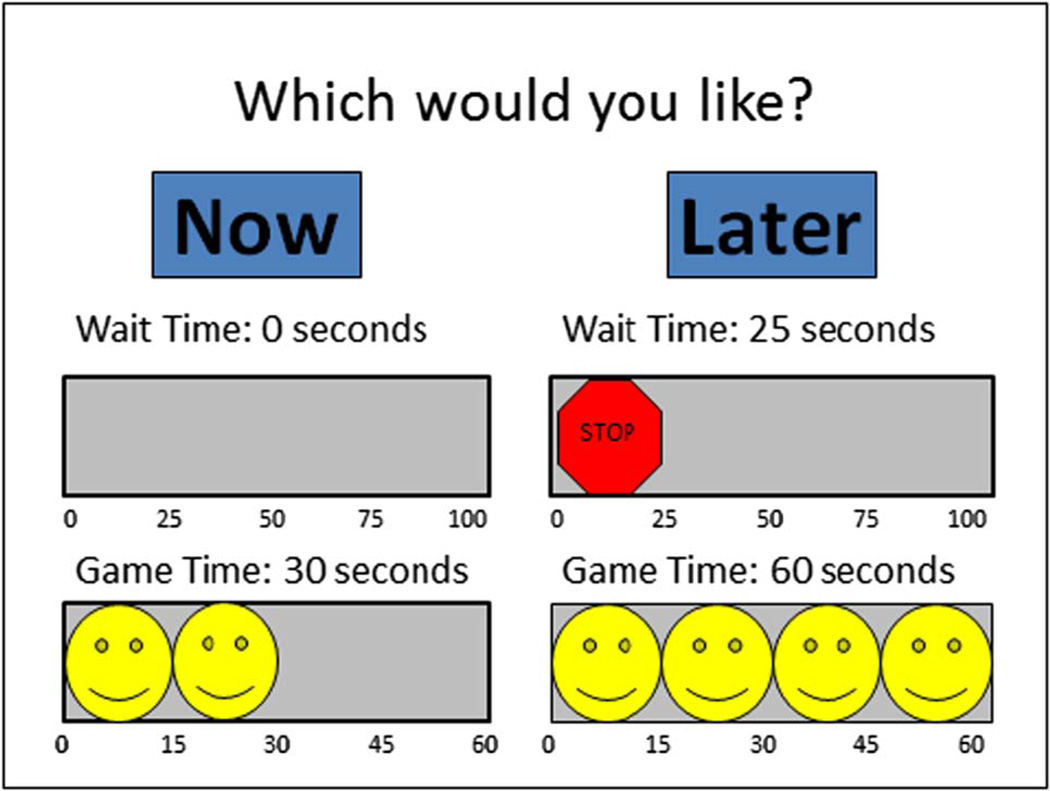

We developed a novel real-time delay discounting task involving immediately consumable rewards and variable reward and delay amounts, an advancement from most previous designs which have primarily used monetary rewards (c.f., Forzano & Logue, 1994; Logue et al., 1996; Millar & Navarick, 1984). During this task, participants make nine choices between getting to play a preferred game for a shorter amount of time (either 15, 30, or 45 s) immediately or for a fixed longer amount of time (60 s) after waiting (either 25, 50, or 100 s; see Figure 1). Once the participant makes a choice, they experienced the delays and rewards associated with that choice in real-time before making their next choice.

Fig. 1.

Novel Real-Time Discounting Task choice presentation screen. This trial represents a choice between playing a preferred game for 30 s immediately (left option) or playing a game for 60 s after a delay of 25 s (right option).

For example, the participant would have to wait 25 s to play a game for 60 s if they chose the “Later” option in Figure 2. The trial duration was held constant at 160 s (i.e., the length of the longest possible trial when the child chooses to wait 100 s to play for 60 s) regardless of the child’s choice by imposing an adjusting post-reward delay. Participants could bring their own game and were offered several game options (handheld video game, coloring, Legos, etc.) to maximize the rewarding value for each individual. Their preferred game was placed in a clear box in front of them when they made their choices and while waiting to play. This task involved two practice choices, during which participants experienced both the immediate and delayed options, followed by nine test choices and took 40 min to complete. The immediate reward values were presented in ascending order within each delay and the order of the delays was fully counterbalanced across subjects.

Fig. 2.

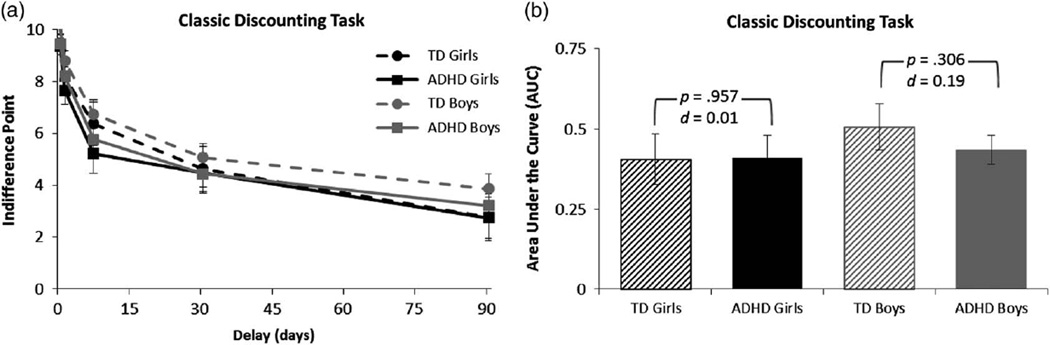

Choice preferences on the Classic Discounting Task. a: The mean indifference point (adjusted for the model covariate, GAI) for each delay and b: the area under the curve (AUC) (adjusted for the model covariate, GAI) are plotted separately for girls and boys with ADHD and typically developing (TD) girls and boys. Error bars represent standard error of the mean; d = Cohen’s d effect size estimate. There were no significant main effects of diagnosis or sex nor was there a Diagnosis × Sex interaction for delay discounting (AUC) on this task.

Subjective Ratings

A brief subjective measure of the participant’s experience of waiting and reward delivery during the real-time task was also obtained on a subset of the sample (TD: 32 boys, 11 girls; ADHD: 38 boys, 11 girls). After selecting a game to play, participants were asked (1) “How much do you want to play the game?” Ratings were provided on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (I don’t want to play it at all) to 10 (I really want to play it!). After completing the task, participants were asked (2) “How much did you like playing the game?” and (3) “How much did you like waiting to play the game?” Ratings were provided on a likert scale ranging from 1 (I didn’t like it at all) to 10 (I really liked it a lot!).

Data Reduction

The primary dependent variable derived from each discounting task was the area under the curve (AUC) calculated based on the indifference point for each delay. For the classic discounting task, the indifference point was defined as midway between the smallest value of the immediate alternative consistently accepted and the largest value consistently rejected for each delay (Wilson et al., 2011). For the real-time discounting task, the indifference point was defined as the lowest immediate value selected for each delay. These indifference points were used to determine the AUC (Myerson, Green, & Warusawitharana, 2001), a common approach to analyzing discounting data (e.g., Reynolds, Penfold, & Patak, 2008; Scheres, Tontsch, Thoeny, & Sumiya, 2014; Shiels et al., 2009) that eliminates some of the problems associated with measures assuming a hyperbolic function. Smaller AUC values indicate greater delay discounting and greater impulsivity. The AUC was calculated in excel (Reed, Kaplan, & Brewer, 2012).

Data Analysis

The AUC was analyzed for each task, providing a single value to quantify delay discounting. As an initial screen for nonsystematic data, we applied Johnson and Bickel’s (2008) model-free method based on the assumption that indifference points should get smaller as delay increases. Specifically, data are considered to be nonsystematic if any indifference point is larger than the indifference point associated with the adjacent shorter delay by more than 20% of the delayed reward. Based on these criteria, data from 28 children (23%) were deemed invalid on one or both of the delay discounting tasks. Analyses were conducted with and without participants with nonsystematic data and the results were qualitatively similar. Therefore, all participants were retained in the analyses reported below.

Separate univariate analyses of covariance (ANCOVA models) were used for each task with the between-subjects factors of diagnosis (ADHD vs. TD) and sex (girls vs. boys). The WISC-IV general ability index (GAI), a measure of intellectual reasoning ability, was included as a covariate for all analyses examining diagnostic group differences given the evidence for associations among intelligence and delay discounting (Shamosh & Gray, 2008). We chose to use GAI as a covariate in the analyses rather than FSIQ because FSIQ is influenced by difficulties in working memory and processing speed, which are often present in children with ADHD. In contrast, GAI is based on verbal and perceptual reasoning abilities and may, therefore, be a more appropriate measure of broad intellectual ability in children with ADHD. However, all analyses were also conducted without covarying for GAI, with FSIQ instead of GAI as a covariate, and without children with comorbid ODD, and the results did not change. Therefore, only results with GAI as a covariate for the full sample of children with ADHD (including those with comorbid ODD) are reported below.

Subjective ratings were examined with a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with the ratings provided for each of the three questions as the dependent variables and diagnosis and sex as the between-subjects factors. Cohen’s d is reported as a measure of effect size for diagnostic group differences (Cohen, 1988). Bivariate correlations were also conducted in the overall sample examining associations among (1) delay discounting on each task (AUC) and ADHD symptom domains (ADHD-RS raw score for ADHD Inattentive and Hyperactive/Impulsive Scales) and (2) delay discounting on the real-time task and subjective ratings.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Demographic information for the sample is provided in Table 1, along with inferential statistics regarding diagnostic group differences and sex differences within the ADHD sample. The sample was drawn from largely middle class socioeconomic status and was 65% white, 17% African American, 15% biracial, and 3% Asian. Diagnostic groups did not differ in several important demographics including age, sex, ethnicity, and SES. The ADHD group had lower FSIQ, as is often seen in the childhood ADHD literature (Frazier, Demaree, & Youngstrom, 2004). Girls and boys with ADHD also did not differ in age, sex, ethnicity, and SES, nor did they differ in current use of stimulant medication, comorbid ODD, or parent ratings of ADHD symptoms (ADHD-RS Inattention and Hyperactive/Impulsive raw scores).

Table 1.

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics.

| TD |

ADHD |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys (n = 40) | Girls (n = 15) | All (n = 55) | Boys (n = 46) | Girls (n = 19) | All (n = 65) | TD vs. ADHD | ADHD boys vs. girls |

Boys TD vs. ADHD |

Girls TD vs. ADHD |

|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-value | p-value | p-value | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 10.1 (1.2) | 10.2 (1.0) | 10.1 (1.2) | 9.7(1.3) | 9.8(1.1) | 9.8(1.2) | .105 | .835 | .218 | .262 |

| Sex (% girls) | n/a | n/a | 27% | n/a | n/a | 29% | .813 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian) | 63% | 80% | 67% | 67% | 53% | 63% | .631 | .262 | .635 | .097 |

| SESa | 52.0 (8.6) | 52.6 (10.0) | 52.2 (8.9) | 53.2 (10.0) | 50.5(11.5) | 52.5 (10.4) | .860 | .366 | .552 | .587 |

| WISC-IV FSIQ | 117.1 (12.0) | 113.1 (10.1) | 116.0(11.6) | 107.4(11.9) | 108.5 (12.5) | 107.7 (12.0) | <.001 | .748 | <.001 | .257 |

| WISC-IV GAI | 120.6 (12.4) | 112.3(11.1) | 118.3(12.5) | 111.6(13.0) | 111.2(11.6) | 111.5(12.6) | .004 | .906 | .002 | .780 |

| WISC-IV VCI | 121.9(11.6) | 113.8(11.1) | 119.7(11.9) | 113.0(13.6) | 110.4(10.6) | 112.2(12.8) | .001 | .451 | .002 | .366 |

| WISC-IV PRI | 113.0(12.4) | 106.6 (12.9) | 111.2(12.8) | 108.4(11.5) | 108.2(11.9) | 108.4(11.5) | .198 | .944 | .082 | .708 |

| WISC-IV WMI | 112.7(14.4) | 110.7(13.0) | 112.2(14.0) | 103.2 (12.0) | 101.5(15.1) | 102.7 (12.9) | <.001 | .619 | .001 | .068 |

| WISC-IV PSI | 100.5 (14.3) | 107.5 (11.8) | 102.4 (13.9) | 92.4 (10.9) | 101.8 (14.8) | 95.2 (12.8) | .004 | .006 | .004 | .232 |

| Stimulant Medication (%) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 61% | 47% | 57% | n/a | .317 | n/a | n/a |

| Comorbid ODD (%) | 0% | 0% | 0% | 39% | 53% | 43% | n/a | .317 | n/a | n/a |

| ADHD-RS IA | 3.4 (3.0) | 2.7 (2.8) | 3.2 (2.9) | 19.1 (4.7) | 20.1 (4.6) | 19.3 (4.6) | <.001 | .447 | <.001 | <.001 |

| ADHD-RS HI | 2.7 (2.5) | 1.6 (1.7) | 2.4 (2.4) | 15.9 (6.3) | 15.6 (7.0) | 15.8 (6.5) | <.001 | .859 | <.001 | <.001 |

SES was missing for 1 TD and 2 ADHD participants.

SES = Socio-economic status from Hollingshead total score; WISC-IV = Wechsler Scale for Children, Fourth Edition; FSIQ = Full Scale Intelligence Quotient; GAI = General Ability Index; VCI = Verbal Comprehension Index; PRI = Perceptual Reasoning Index; WMI = Working Memory Index; PSI = Processing Speed Index; ADHD-RS IA = ADHD Rating Scale Home Version Inattention raw score; ADHD-RS HI = ADHD Rating Scale Home Version Hyperactive/Impulsive raw score.

Classic “Real-Reward” Discounting Task

On the classic discounting task, there were no differences in delay discounting (AUC) between the diagnostic groups, F(1,115) = 0.3, p = .606, d = .10. There was also no evidence of overall sex differences in delay discounting, F(1,115) = 1.0, p = .324, nor was there a Diagnosis × Sex interaction, F(1,115) = 0.4, p = .542, d = .11 (see Figure 2).1

Novel “Real-Time” Discounting Task

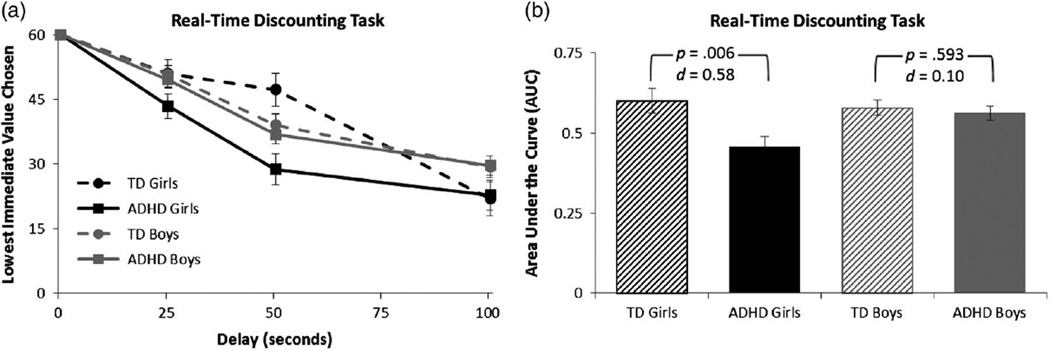

On the novel real-time discounting task, during which participants experienced the delays and rewards associated with their choices in real-time, children with ADHD displayed greater delay discounting (AUC) as evidenced by a main effect of diagnosis, F(1,115) = 6.8, p = .010, d = .48. However, this main effect was qualified by a Diagnosis × Sex interaction, F(1,115) = 4.2, p = .044, d = .38, such that girls with ADHD showed greater delay discounting compared to TD girls (p = .006; d = 0.58), whereas delay discounting did not differ among boys with ADHD compared to TD boys (p = .593; d = 0.10) (see Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Choice preferences on the Novel Real-Time Discounting Task. a: The mean indifference point (adjusted for the model covariate, GAI) for each delay b: and the area under the curve (AUC) (adjusted for the model covariate, GAI) are plotted separately for girls and boys with ADHD and typically developing (TD) girls and boys. Error bars represent standard error of the mean; d = Cohen’s d effect size estimate. There was a significant main effect of diagnosis that was qualified by a Diagnosis × Sex interaction for delay discounting (AUC) on this task.

Subjective Ratings

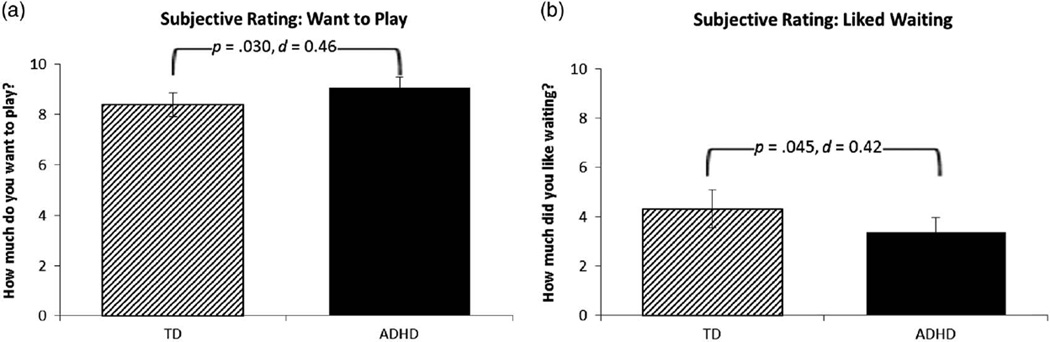

Results of the MANOVA for the three subjective ratings provided by participants indicated an overall effect of diagnosis, F(3,89) = 3.3, p = .024, d = .38, but no main effect of sex, F(3,89) = 0.4, p = .638, nor was there a Diagnosis × Sex interaction, F(3,89) = 0.6, p = .638, d = .16. Examination of the between-subjects effects for each question suggested that children with ADHD reported wanting to play their chosen game more than TD children before making their choices (i.e., reward desirability, p = .030; see Figure 4a) and liking waiting less than TD children after making their choices (i.e., difficulty waiting, p = .045; see Figure 4b), whereas there was no difference between diagnostic groups in their rating of how much they liked playing their chosen game (p = .538).

Fig. 4.

Subjective ratings obtained for the novel real-time discounting task. (a) Mean rating on a 1–10 likert scale in response to the question “How much do you want to play the game?” asked after selecting a preferred game and before making choices. (b) Mean rating on a 1–10 likert scale in response to the question “How much did you like waiting to play the game?” asked after completing all choices. Higher values indicate wanting to play more and liking waiting more. Error bars represent standard error of the mean; d = Cohen’s d effect size estimate. Children with ADHD reported wanting to play their chosen game more than TD children (a) and liking waiting less than TD children (b).

Correlations among Delay Discounting, ADHD Symptoms, and Subjective Ratings

Examination of bivariate correlations indicated that greater inattentive symptoms were significantly correlated with greater discounting (i.e., smaller AUC) on the classic discounting task (r = −.199; p = .030), but not on the real-time task (r = −.158; p = .086). Hyperactive/impulsive symptoms were not significantly correlated with delay discounting on either the classic discounting task (r = −.153; p = .099) or the real-time discounting task (r = −.130; p = .159). Subjective ratings of reward desirability, experience of reward, and difficulty rating were not significantly correlated with delay discounting on the real-time task (rs<.12; ps>.26).

DISCUSSION

The current study examined delay discounting among 8- to 12-year-old girls and boys with ADHD-C relative to TD controls on two tasks that differed in the extent to which the delays and rewards were experienced by participants. Consistent with theoretical models of ADHD emphasizing altered reinforcement sensitivity (Luman et al., 2010), children with ADHD displayed greater delay discounting. However, this finding was specific to girls with ADHD and to the task in which the rewards were immediately consumable (i.e., playing a game) and the delays were experienced in real-time. Furthermore, children with ADHD reported wanting to play their preferred game more than TD controls and liking waiting to play less than TD controls, although they did not significantly differ in their rating of how much they liked playing their chosen game. ADHD inattentive symptoms were significantly correlated with greater discounting on the classic discounting task.

This is the first study to show ADHD-related sex differences in delay discounting, such that only girls with ADHD showed greater discounting of playing a preferred game during a real-time discounting task. Interpretation of this finding is guided by consideration of the lack of diagnostic group differences among girls and boys in delay discounting on the classic discounting task, similar to tasks commonly used in the ADHD literature. The finding of similar discounting rates among ADHD and TD children, regardless of sex, on the classic discounting task is consistent with some previous studies (Chantiluke et al., 2014; Crunelle et al., 2013; Rubia et al., 2009; Wilbertz et al., 2013, 2012), although other studies have reported greater discounting among individuals with ADHD on similar tasks (Costa Dias et al., 2013; Dai et al., 2013; Demurie et al., 2012, 2013; Hurst et al., 2011; Paloyelis et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2011). The discrepant findings from those of Wilson and colleagues (2011) may be particularly informative given our use of a nearly identical task, except for participants being told that some of the choices were real. Consideration of characteristics of the sample or task that differed across these studies may inform our understanding of the inconsistent findings in the broader ADHD delay discounting literature.

First, it is important to consider the role of intellectual ability, both in terms of the greater difference in FSIQ between the ADHD and TD samples in the Wilson et al. (2011) study (13-point difference: ADHD = 105; TD = 118) compared to our study (8-point difference: ADHD =108; TD =116) and the relatively higher IQ of our ADHD sample than is typically reported in the ADHD literature (e.g., Parke, Thaler, Etcoff, & Allen, 2015 report an average FSIQ of 102). Differences in IQ between ADHD and control samples are often reported, but it has been suggested that covarying for IQ may be inappropriate as this would control for a component of the disorder (Dennis et al., 2009). This issue is particularly relevant for delay discounting studies given that higher intelligence is associated with lower delay discounting (see meta-analysis by Shamosh & Gray, 2008), although the contribution of IQ is not consistently addressed in ADHD delay discounting studies. Wilson et al. (2011) reported that the significant diagnostic group difference in discounting was eliminated after controlling for IQ, whereas the results did not change in our study regardless of whether FSIQ or GAI was included as a covariate. The relatively high IQ of our ADHD sample may reduce the potential confound of IQ differences in delay discounting studies of individuals with ADHD, but it may also limit the generalizability of our findings. Interestingly, GAI was correlated with discounting on the classic discounting task in the current study (r = .235; p = .020), but not with the real-time task (r = .100; p = .276). This might suggest that intelligence is more strongly related to decision-making on tasks involving primarily abstract and long-term decisions whereas choices in which the delays and rewards are experienced in real-time are less influenced by intellectual ability. Further research is warranted to better understand the relationship between intelligence and delay discounting.

The role of inattention may have also contributed to the discrepant findings. Specifically, Wilson et al. (2011) included younger children (7–9 year olds vs. 8–12 year olds in our study) and participants with the predominantly inattentive subtype of ADHD (41% vs. all combined subtype in our study). These sample characteristics, along with the use of hypothetical rewards, may have resulted in greater inattention to the task and likely influenced the discounting slopes. The diagnostic group differences were no longer significant after controlling for attention to task (based on how they answered attention check questions), suggesting that Wilson et al.’s finding of greater delay discounting among children with ADHD may have been due to greater inattention rather than a heightened preference for immediate reward. The use of real rather than hypothetical rewards in our study may have improved participants’ attention to each choice, resulting in more accurate measurement of delay discounting. It is unclear how this procedural difference impacts delay discounting among children, although studies with adults have shown that real and hypothetical rewards are discounted to the same degree (e.g., Lagorio & Madden, 2005; Madden et al., 2003).

Although theories of ADHD postulate stronger associations among delay discounting and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms than inattentive symptoms (Sagvolden, Johansen, Aase, & Russell, 2005), studies examining the association among ADHD symptom domains and delay discounting suggest that correlations with symptoms may be task dependent such that hyperactive/impulsive symptoms are associated with discounting on real-time tasks (Scheres & Hamaker, 2010; Scheres et al., 2008), while inattention symptoms are associated with discounting on classic discounting tasks involving all or mostly hypothetical rewards as shown in the current study and in the study by Wilson et al. (2011). The latter task typically involves many more choices, which may place greater demands on attention. However, our sample only included girls and boys with ADHD-C who did not differ in parent ratings of inattention or hyperactive/ impulsive symptoms, suggesting that our findings may reflect a true sex difference rather than an artifact of symptom presentation.

Our finding of greater discounting in children with ADHD on a real-time task is consistent with two previous studies using real-time paradigms (Scheres et al., 2010; Schweitzer & Sulzer-Azaroff, 1995), although these studies involved choices about money, which has limited utility in the moment compared to an immediately consumable reward. Sex differences were not addressed in either of these studies due to insufficient power (only 6 girls with ADHD in Scheres et al., 2010) or an exclusively male sample (Schweitzer & Sulzer-Azaroff, 1995). However, it is interesting that these studies found evidence of greater delay discounting on a real-time task among boys with ADHD, whereas we did not. This might suggest that the use of immediately consumable rewards may be an important procedural difference from previous studies reporting greater preference for immediate reward in primarily male ADHD samples. Perhaps boys with ADHD were better able to exert self-control and wait for the larger, delayed reward when it was a primary rather than a secondary reinforcer delivered in real-time, as in previous studies. In contrast, girls with ADHD may show a diminished response to reward as shown in a previous study (Rosch et al., 2015) and perhaps a greater aversion to delay, which they actually experienced during this task, which may have led to a stronger preference for immediate reward.

Alternatively, girls with ADHD may have been differentially sensitive to the delay amount or the type of reward. Studies have shown commodity or domain-dependence of discounting rates (Chapman & Elstein, 1995), such that healthy adults discount hypothetical monetary rewards more steeply than hypothetical consumable rewards, such as cigarettes, food, alcohol, and entertainment (e.g., Friedel, DeHart, Madden, & Odum, 2014), and less steeply than hypothetical health outcomes (Chapman & Elstein, 1995). In contrast, children and adolescents (ages 8–16 years) have been shown to discount hypothetical edible rewards, social rewards, and activities more steeply than money (Demurie et al., 2013). However, the rewards used in most previous studies were not actually consumed in real-time, as was done in the current study, which may limit the comparisons that can be made. Further research is necessary to improve our understanding of how the type of reward, particularly with regard to whether it is an immediately consumable primary reinforcer (e.g., food, drugs, entertainment) that is experienced in real-time or a secondary reinforcer (e.g., money), impacts impulsive decision-making in ADHD. The classic and real-time discounting tasks in this study also differed with regard to the length of the delays, which may impact delay discounting. Thus, it may be that girls with ADHD were differentially sensitive to the length of the delays across the two tasks whereas other children did not display this sensitivity. In future research, it will be important to examine whether these apparent sex differences are a function of the potential for reward consumption, delay amount, or different commodities.

Comparison of diagnostic groups on subjective ratings of reward desirability, experience of reward, and difficulty waiting during the real-time task expand upon the results of Scheres et al. (2013), in which subjective ratings of difficulty waiting were associated with delay discounting. In the current study, children with ADHD reported wanting to play their preferred game more than TD controls (before completing the task) and liking waiting to play less than TD controls (after completing the task), although they did not significantly differ in their rating of how much they liked playing their chosen game. Thus, it may be that a stronger preference for immediate reward among children with ADHD is related to a combination of greater reward desirability and more difficulty waiting, although differences in discounting were only observed among girls in the current sample. Interestingly, subjective ratings were not significantly correlated with delay discounting on the real-time task. Our approach differed from that of Scheres et al. (2013) in that we obtained objective ratings for the overall task rather than for each choice trial, which may provide a more sensitive measure of how subjective feelings related to decision making.

It is important to consider these findings within context of the study’s limitations. First, although our sample of girls with ADHD (n = 19) is larger than in previous studies of delay discounting, this sample is relatively small and replication with larger samples of girls is important. In addition, the lack of comorbidities other than ODD in our sample of children with ADHD and the relatively high IQ of our ADHD sample may limit comparisons with other studies involving clinical samples of children with ADHD. It will be important for future studies attempting to replicate these findings to include larger samples of girls with ADHD and children with comorbid disorders beyond ODD to determine whether these findings generalize to samples representative of the broader population of children with ADHD. Another limitation of this study is that we did not examine other neurocognitive measures that may be related to delay discounting and may differ between girls and boys with ADHD, such as working memory, inhibitory control, and time perception.

In sum, these findings provide novel information about sex differences in delay discounting among children with ADHD and the importance of considering task characteristics as well as ratings of the subjective experience of reward desirability and waiting. These findings encourage future work investigating sex differences in relation to impulsive decision-making in ADHD and emphasize the importance of multi-method assessment of delay discounting. Further research examining the contribution of intelligence to delay discounting is also warranted, particularly given the differential associations with the tasks used in the current study. Finally, research exploring the neural correlates of delay discounting in children with ADHD will be important for elucidating the relative contribution of cognitive control and reward systems to impulsive decision-making in ADHD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (RO1 MH078160, RO1 MH085328, K23 MH101322) and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institute for Clinical and Translational Research National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources Clinical and Translational Science Award program UL1 TR 000424-06. The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

For the classic discounting task, the natural log of the k-value was also examined to allow for comparisons with the existing literature. The findings were similar to those reported here for AUC (covarying for GAI) in that there were no significant effects of diagnosis, F(1, 113) = 0.7, p = .419, or interactions with sex, Diagnosis×Sex, F(1, 113) =0.004, p = .952. A similar pattern was observed when GAI was not included as a covariate.

REFERENCES

- Antrop I, Stock P, Verte S, Wiersema JR, Baeyens D, Roeyers H. ADHD and delay aversion: The influence of non-temporal stimulation on choice for delayed rewards. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(11):1152–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Edwards G, Laneri M, Fletcher K, Metevia L. Executive functioning, temporal discounting, and sense of time in adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29(6):541–556. doi: 10.1023/a:1012233310098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidwell LC, Willcutt EG, Defries JC, Pennington BF. Testing for neuropsychological endophenotypes in siblings discordant for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62(9):991–998. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Mick E, Spencer T, Wilens TE, Silva JM, Faraone SV. Young adult outcome of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A controlled 10-year follow-up study. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(2):167–179. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsakou P, Psychogiou L, Thompson M, Sonuga-Barke EJ. Delay Aversion in Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: An empirical investigation of the broader phenotype. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47(2):446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantiluke K, Christakou A, Murphy CM, Giampietro V, Daly EM, Ecker C, Rubia K. Disorder-specific functional abnormalities during temporal discounting in youth with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autism and comorbid ADHD and Autism. Psychiatry Research. 2014;223(2):113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman GB, Elstein AS. Valuing the future: Temporal discounting of health and money. Medical Decision Making. 1995;15(4):373–386. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghill DR, Seth S, Matthews K. A comprehensive assessment of memory, delay aversion, timing, inhibition, decision making and variability in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Advancing beyond the three-pathway models. Psychological Medicine. 2013:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Conners’ Rating Scales- Revised. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Conners 3. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Costa Dias TG, Wilson VB, Bathula DR, Iyer SP, Mills KL, Thurlow BL, Fair DA. Reward circuit connectivity relates to delay discounting in children with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;23(1):33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crunelle CL, Veltman DJ, van Emmerik-van Oortmerssen K, Booij J, van den Brink W. Impulsivity in adult ADHD patients with and without cocaine dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;129(1–2):18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z, Harrow SE, Song X, Rucklidge J, Grace R. Gambling, delay, and probability discounting in adults with and without ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1087054713496461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalen L, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Hall M, Remington B. Inhibitory deficits, delay aversion and preschool AD/HD: Implications for the dual pathway model. Neural Plasticity. 2004;11(1–2):1–11. doi: 10.1155/NP.2004.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demurie E, Roeyers H, Baeyens D, Sonuga-Barke E. Temporal discounting of monetary rewards in children and adolescents with ADHD and autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Science. 2012;15(6):791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demurie E, Roeyers H, Baeyens D, Sonuga-Barke E. Domain-general and domain-specific aspects of temporal discounting in children with ADHD and autism spectrum disorders (ASD): A proof of concept study. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2013;34(6):1870–1880. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Francis DJ, Cirino PT, Schachar R, Barnes MA, Fletcher JM. Why IQ is not a covariate in cognitive studies of neurodevelopmental disorders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2009;15:331–343. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709090481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derks EM, Hudziak JJ, Boomsma DI. Why more boys than girls with ADHD receive treatment: A study of Dutch twins. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10(5):765–770. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.5.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R. ADHD Rating Scale—IV. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Forzano LB, Logue AW. Self-control in adult humans: Comparison of qualitatively different reinforcers. Learning and Motivation. 1994;25(1):65–82. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/lmot.1994.1004. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier TW, Demaree HA, Youngstrom EA. Meta-analysis of intellectual and neuropsychological test performance in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychology. 2004;18(3):543–555. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.18.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedel JE, DeHart WB, Madden GJ, Odum AL. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: Discounting of monetary and consumable outcomes in current and non-smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2014;231(23):4517–4526. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3597-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaub M, Carlson CL. Gender differences in ADHD: A meta-analysis and critical review. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(8):1036–1045. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199708000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Kar BR. Development of attentional processes in ADHD and normal children. Progress in Brain Research. 2009;176:259–276. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17614-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson R, Fine JG. Gender differences among children with ADHD on continuous performance tests: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2012;16(3):190–198. doi: 10.1177/1087054711427398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Owens EB, Sami N, Fargeon S. Prospective follow-up of girls with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adolescence: Evidence for continuing cross-domain impairment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(3):489–499. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst RM, Kepley HO, McCalla MK, Livermore MK. Internal consistency and discriminant validity of a delay-discounting task with an adult self-reported ADHD sample. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2011;15(5):412–422. doi: 10.1177/1087054710365993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. An algorithm for identifying nonsystematic delay-discounting data. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;16(3):264–274. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keltner NL, Taylor EW. Messy purse girls: Adult females and ADHD. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2002;38(2):69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagorio CH, Madden GJ. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards III: Steady-state assessments, forced-choice trials, and all real rewards. Behavioural Processes. 2005;69(2):173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logue AW, Forzano LB, Ackerman KT. Self-control in children: Age, preference for reinforcer amount and delay, and language ability. Learning and Motivation. 1996;27(3):260–277. [Google Scholar]

- Luman M, Tripp G, Scheres A. Identifying the neurobiology of altered reinforcement sensitivity in ADHD: A review and research agenda. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2010;34(5):744–754. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Begotka AM, Raiff BR, Kastern LL. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11(2):139–145. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco R, Miranda A, Schlotz W, Melia A, Mulligan A, Muller U, Sonuga-Barke EJ. Delay and reward choice in ADHD: An experimental test of the role of delay aversion. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(3):367–380. doi: 10.1037/a0014914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY, Hinshaw SP, Lee SS, Mullin BC. Relationships between social information processing and aggression among adolescent girls with and without ADHD. Journal of Youth and Adolescents. 2008;37(7):761–771. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar A, Navarick DJ. Self-control and choice in humans: Effects of video game playing as a positive reinforcer. Learning and Motivation. 1984;15(2):203–218. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0023-9690(84)90030-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Metzner R. Preference for delayed reward as a function of age, intelligence, and length of delay interval. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1962;64:425–431. doi: 10.1037/h0045046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mischel W, Underwood B. Instrumental ideation in delay of gratification. Child Development. 1974;45(4):1083–1088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L, Warusawitharana M. Area under the curve as a measure of discounting. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2001;76(2):235–243. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2001.76-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien JW, Dowell LR, Mostofsky SH, Denckla MB, Mahone EM. Neuropsychological profile of executive function in girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2010;25(7):656–670. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acq050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paloyelis Y, Asherson P, Mehta MA, Faraone SV, Kuntsi J. DAT1 and COMT effects on delay discounting and trait impulsivity in male adolescents with attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder and healthy controls. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(12):2414–2426. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke EM, Thaler NS, Etcoff LM, Allen DN. Intellectual profiles in children with ADHD and comorbid learning and motor disorders. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1087054715576343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed DD, Kaplan BA, Brewer AT. A tutorial on the use of Excel 2010 and Excel for Mac 2011 for conducting delay-discounting analyses. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45(2):375–386. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2012.45-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich W, Welner Z, Herjanic B. The Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents-IV. North Tonawanda: Multi-Health Systems; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B. A review of delay-discounting research with humans: Relations to drug use and gambling. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2006;17(8):651–667. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280115f99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Ortengren A, Richards JB, de Wit H. Dimensions of impulsive behavior: Personality and behavioral measures. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40(2):305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Penfold RB, Patak M. Dimensions of impulsive behavior in adolescents: Laboratory behavioral assessments. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;16(2):124–131. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosch KS, Dirlikov B, Mostofsky SH. Reduced intrasubject variability with reinforcement in boys, but not girls, with ADHD: Associations with prefrontal anatomy. Biological Psychology. 2015;110:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Halari R, Christakou A, Taylor E. Impulsiveness as a timing disturbance: Neurocognitive abnormalities in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder during temporal processes and normalization with methylphenidate. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 2009;364(1525):1919–1931. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucklidge JJ. Gender differences in attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2010;33(2):357–373. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagvolden T, Johansen EB, Aase H, Russell VA. A dynamic developmental theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) predominantly hyperactive/impulsive and combined subtypes. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2005;28(3):397–419. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000075. discussion 419-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres A, Dijkstra M, Ainslie E, Balkan J, Reynolds B, Sonuga-Barke E, Castellanos FX. Temporal and probabilistic discounting of rewards in children and adolescents: Effects of age and ADHD symptoms. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44(11):2092–2103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres A, Hamaker EL. What we can and cannot conclude about the relationship between steep temporal reward discounting and hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(4):e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres A, Lee A, Sumiya M. Temporal reward discounting and ADHD: Task and symptom specific effects. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2008;115(2):221–226. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0813-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres A, Tontsch C, Thoeny AL. Steep temporal reward discounting in ADHD-Combined type: Acting upon feelings. Psychiatry Research. 2013;209(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres A, Tontsch C, Thoeny AL, Kaczkurkin A. Temporal reward discounting in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: The contribution of symptom domains, reward magnitude, and session length. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67(7):641–648. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres A, Tontsch C, Thoeny AL, Sumiya M. Temporal reward discounting in children, adolescents, and emerging adults during an experiential task. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5:711. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer JB, Sulzer-Azaroff B. Self-control in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Effects of added stimulation and time. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36(4):671–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb02321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour KE, Mostofsky SH, Rosch KS. Cognitive load differentially impacts response control in girls and boys with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-9976-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamosh NA, Gray JR. Delay discounting and intelligence: A meta-analysis. Intelligence. 2008;36(4):289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Shiels K, Hawk LW, Reynolds B, Mazzullo RJ, Rhodes JD, Pelham WE, Gangloff BP. Effects of methylphenidate on discounting of delayed rewards in attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Experimental and Clinical Psycho-pharmacology. 2009;17(5):291–301. doi: 10.1037/a0017259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanto MV, Abikoff H, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Schachar R, Logan GD, Wigal T, Turkel E. The ecological validity of delay aversion and response inhibition as measures of impulsivity in AD/HD: A supplement to the NIMH multimodal treatment study of AD/HD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29(3):215–232. doi: 10.1023/a:1010329714819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solanto MV, Gilbert SN, Raj A, Zhu J, Pope-Boyd S, Stepak B, Newcorn JH. Neurocognitive functioning in AD/HD, predominantly inattentive and combined subtypes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35(5):729–744. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9123-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJ, Taylor E, Sembi S, Smith J. Hyperactivity and delay aversion-I. The effect of delay on choice. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1992;33(2):387–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1992.tb00874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlstedt C, Thorell LB, Bohlin G. Heterogeneity in ADHD: Neuropsychological pathways, comorbidity and symptom domains. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37(4):551–564. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler DL. Wechsler Individual Achievement Test -Second Edition (WIAT-II) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler DL. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children -Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wilbertz G, Trueg A, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Blechert J, Philipsen A, Tebartz van Elst L. Neural and psychophysiological markers of delay aversion in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122(2):566–572. doi: 10.1037/a0031924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbertz G, van Elst LT, Delgado MR, Maier S, Feige B, Philipsen A, Blechert J. Orbitofrontal reward sensitivity and impulsivity in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuroimage. 2012;60(1):353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson VB, Mitchell SH, Musser ED, Schmitt CF, Nigg JT. Delay discounting of reward in ADHD: Application in young children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52(3):256–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley CA, Eagle DM, Robbins TW. Behavioral models of impulsivity in relation to ADHD: Translation between clinical and preclinical studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(4):379–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodka EL, Loftis C, Mostofsky SH, Prahme C, Larson JC, Denckla MB, Mahone EM. Prediction of ADHD in boys and girls using the D-KEFS. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2008;23(3):283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]