Abstract

Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) represent exciting therapeutic targets for the treatment of multiple CNS disorders. The high degree of conservation of amino acids comprising the orthosteric acetylcholine (ACh) binding site between individual mAChR subtypes has hindered the development of subtype-selective compounds that bind to this site. As a result, many academic and industry researchers are now focusing on developing allosteric activators of mAChRs including both positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) and allosteric agonists. In the past 10 years major advances have been achieved in the discovery of allosteric ligands that possess much greater selectivity for individual mAChR subtypes when compared to previously developed orthosteric agents. These novel allosteric modulators of mAChRs may provide therapeutic potential for treatment of a number of CNS disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia.

Introduction

Cholinergic projection neurons in the basal forebrain extend from the medial septum through the nucleus basalis of Meynert (nbM) and provide the primary source of ACh to brain regions including the neocortex and hippocampus.1–4 These neurons influence several aspects of CNS function including information processing, learning and memory, cognition, motor control and attention.5,6 Several lines of evidence implicate impaired cholinergic neurotransmission in these brain regions as contributing to the symptoms of a wide variety of CNS disorders. Pharmacological blockade or physical lesions in basal forebrain neurons in animal models7–15 and humans16,17 mimic symptoms commonly observed in patients suffering from Alzheimer’s disease (AD); furthermore, degeneration of cholinergic inputs to the forebrain is one of the earliest pathological changes observed in AD patients.4,18 Decreased mAChR abundance and impaired mACh receptor coupling have also been observed in post mortem forebrain tissues from individuals with schizophrenia.19–22 These findings support the hypothesis that dysfunction of the cholinergic system, at least in part, underlies behavioral impairments associated with multiple CNS disorders. Because of this, many efforts have been made to develop clinically useful compounds that enhance cholinergic signaling in the brain.

One class of cholinergic drugs commonly used to ameliorate symptoms of AD is acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors. These compounds inhibit the activity of the enzyme AChE which degrades synaptic ACh not only in the brain but at nerve terminals in the periphery. In doing so, they cause increased ACh-mediated signaling and have been shown to enhance memory formation and decrease the occurrence of dementia-related behavioral disturbances. For these reasons, they remain the primary treatment for patients suffering from CNS disorders such as AD. Indeed, dose-related improvements in cognitive performance and quality of life are routinely observed in AD patients using AChE inhibitors;23 however, activation of cholinergic receptors in the heart, GI tract, and secretory glands induces unwanted, poorly tolerated side effects such as vomiting and nausea that limit the therapeutic index of these drugs.24 Consequently, there is a need for agents that increase cholinergic signaling in a more selective manner than AChE inhibitors.

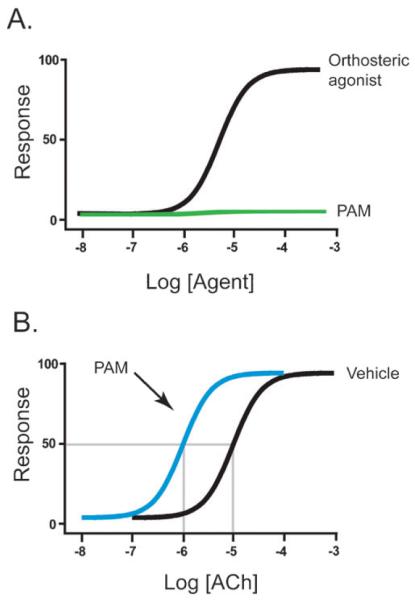

Two families of receptors mediate the action of ACh in target tissues: nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs), which function as ligand-gated cation channels, and mucsarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs), which are members of the G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) superfamily. Historically, most CNS drug development efforts have focused on mAChR subtypes because these receptors have more established roles in attention mechanisms and learning and memory.4,18 Molecular cloning studies have identified five mAChR subtypes denoted M1–M5.25–29. Each subtype is a single seven-transmembrane protein, which when stimulated by ACh, activates GTP-binding proteins (G proteins) that couple to various downstream effectors. M1, M3, and M5 receptors have been shown to activate phospholipase C via pertussis toxin (PTX)-insensitive G proteins whereas M2/M4 receptors inhibit adenylyl cyclase via PTX-sensitive G proteins29 (Fig. 1). All subtypes can activate extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), a signaling protein involved in cell growth, differentiation, cell survival, and multiple CNS functions.30

Fig. 1.

Muscarinic receptor structure and G protein coupling. M1, M3, and M5 AChRs couple to Gαq family G proteins which modulate effectors including PLC whereas M2 and M4 mAChRs couple to Gαi/o family G proteins which modulate effectors such as adenylyl cyclase. It is also important to note that several other effectors can be modulated by active mAChRs (e.g. ion channels and other protein kinases). The amino acids that contribute to the orthosteric binding site of mACh receptors are located in the transmembrane (TM) domain. In contrast, “ectopically” located amino acids contribute to the putative allosteric binding sites on mAChRs.

Studies using highly specific antibodies to each of the individual mAChR subtypes have revealed differential but partially overlapping localization of these subtypes in areas of the brain known to be affected in multiple disorders of the CNS. For example, in neocortex and hippocampus, M1 ACh receptors are the most abundantly expressed muscarinic subtype ranging from 35–60% of all mAChR binding sites.31–33 M1 receptors are also expressed postsynaptically on the somatodendritic regions of pyramidal neurons in the striatum.31,34 Their postsynaptic localization on asymmetric synapses is consistent with M1 having a general role in cholinergic modulation of glutamatergic neurotransmission.31,35 M4 receptors, on the other hand, are modestly expressed in the hippocampus and cortex, but highly enriched in the striatum.31,32,34 M2 receptors are expressed throughout the brain including hippocampus and neocortex, but are also abundant on noncholinergic neurons that project to these areas.31,34 M3 receptors are expressed in the hippocampus whereas M5 receptors are expressed at relatively low levels in the brain.31–33 These localization patterns suggest that each mAChR likely has differential roles in cholinergic modulation of brain circuits. Furthermore, as M1 and M4 expression patterns are abundant in brain regions known to be affected in CNS disorders such as AD and schizophrenia, M1 and M4 have generally been viewed as promising drug targets. Consequently, considerable efforts have been made to develop selective ligands for these subtypes. However, to date, there are no truly selective ligands for M1 or M4 in clinical trials. In the following review, we will explore the advances in development of subtype-selective ligands for M1 and M4 receptors, with a special emphasis on development of allosteric agents which show unprecedented subtype selectivity for these two mAChR subtypes.

The role of M1 receptors in AD highlights the need for subtype-selective muscarinic activators

AD, the most common form of dementia in the elderly, affected 25 million individuals in 2006.36 It is characterized by several distinct neuropathological features including extraneuronal amyloid plaques, intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, and neocortical atrophy as well as an enlargement of ventricles.37 Several findings indicate that failed neurotransmission at cholinergic synapses is responsible, at least in part, for the clinical manifestations associated with AD. For example, decreased levels of choline acetyl transferase (ChAT), the enzyme that synthesizes acetylcholine from acetyl CoA, are routinely observed in post mortem brain tissue from AD patients.38,39 Furthermore, up to 90% degeneration of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain has been observed in these same tissues.40 Localized infusion of the muscarinic antagonist scopolamine into parahippocampal structures of primates has also revealed a role of cholinergic receptors in visual memory as tested by recognition of sample stimuli.41 Additionally, the phenotypes of rodents in which muscarinic receptors have been genetically deleted suggest that mAChRs contribute to the cognition-enhancing effects of ACh.42 These experiments, as well as others, have established that muscarinic cholinergic receptors are the most likely receptors for mediating the cholinergic involvement in learning and memory.7

As discussed above, M1 receptors are the most abundantly expressed mAChR in the neocortex and hippocampus, two regions where cholinergic innervation is lost in AD. For this reason, M1 receptors have been viewed as the most attractive muscarinic therapeutic target for treatment of AD. Recent studies suggest that activation of M1 receptors not only enhances cognition but also decreases multiple pathological features commonly seen in AD patients.43–46 For example, stimulation of M1 has been shown to increase formation of secreted amyloid precursor protein (sAPP) by modulating α-secretase,47 thereby inhibiting the formation of β-secretase products, the precursors of amyloid plaques.48–52 Furthermore, M1 activation reduces neurofibrillary tangles by decreasing tau phosphorylation via GSK-3β inhibition.53 Signaling through the M1 receptor also increases activation of ERK and potentiates NMDA receptor currents, two cellular events considered important for memory formation.54–56 Together, these studies suggest that M1 receptors modulate multiple aspects of AD including learning and memory and cellular neuropathology. Based on this, selective activators of M1 may not only enhance memory but also have disease modifying potential by decreasing the progression of cellular pathologies that develop with AD.

Although M1 receptors are the most abundant mAChR subtype expressed in the hippocampus, their role as being the primary muscarinic subtype essential for learning and memory is less clear. For example, studies employing mice in which the M1 receptor was genetically deleted showed normal or enhanced memory using tasks that involved matching-to-sample problems, but were impaired on non-matching-to-sample tasks.57 Based on this, the authors of this study suggested that M1 mutant mice have impaired hippocampal–cortical interactions causing memory dysfunction specific to working memory and remote reference memory.57 M1 knockout mice also displayed profound hyperactivity making it unclear if some of the cognitive impairments were actually due to the hyperactivity.58,59

Despite this uncertainty, numerous attempts have been made to generate compounds which are selective for the M1 receptor subtype. However, many of these efforts have failed, in part, because these first generation muscarinic agents bind to the highly conserved orthosteric ACh binding site. For example, compounds such as AF102B, AF267B, SB202026, and WAY-132983 were designed to orthosterically bind M1. These agents initially provided important proof of concept evidence that agonism at M1 receptors is a viable approach for treatment of AD and were used in clinical trials. However, they were all subsequently discontinued because of cholinergic side effects.44,60–62 In many cases, these agents were initially thought to be selective for M1 as they displayed selectivity for this mAChR subtype in cell based assays. However, upon further characterization in more native tissues, these agents were subsequently found to be without absolute M1 selectivity. To this end, there is still no truly selective M1 orthosteric agonist available for treatment of AD.

Activation of muscarinic receptors as a novel treatment strategy for schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is characterized by a broad spectrum of symptoms including positive (hallucinations), negative (flattened affect), and cognitive dysfunction (attention and working memory deficits).63 Dysregulation of glutamate and dopamine systems in the brain have been implicated as the main causes for this complex disease. However, it is increasingly evident that the pathology of schizophrenia also involves other neurotransmitter systems. Many sets of data from studies using neuroimaging and animal models suggest a role for the cholinergic system.63–65 Furthermore, decreased levels of mAChR expression, as well as functional impairments in mAChR coupling, have been observed in post-mortem brain tissue from schizophrenic patients.19–22

In the clinic, a recent study using the M1/M4 preferring agonist xanomeline (Xan) (Structure A; Fig. S1‡) has confirmed that targeting the muscarinic cholinergic system is a viable treatment for schizophrenia.66,67 Originally developed as a drug for treatment for AD, Xan induced modest improvements in cognitive function; however, its most robust therapeutic effects were on psychotic symptoms. In a double blind placebo-controlled study, Shekhar et al. showed that Xan induced a highly significant improvement in positive symptoms in schizophrenic patients including vocal outbursts, suspiciousness, agitation, and hallucinations.68 In addition, Xan subjects showed mild improvements in cognitive measures of verbal learning and short-term memory formation suggesting Xan is somewhat efficacious for cognitive dysfunction. Interestingly, the response to Xan was superior to the effects observed with traditional antipsychotics, and therapeutic effects were seen in less than one week, as opposed to the multi week delay for traditional antipsychotics.68 Unfortunately, Xan was not a truly selective M1/M4 agonist and had off-target activity at M2, M3, and M5 receptor subtypes.69–71 Further, Xan had poor brain penetration and required high plasma concentrations to achieve sufficient activation of M1. For these reasons, Xan suffers from the same (mainly GI) side effects as those seen with the use of AChE inhibitors and is not a viable drug candidate for long-term clinical use. Despite this, Xan’s positive effects provide strong clinical validation that targeting of M1/M4 mAChRs is a valid therapeutic strategy for treatment of psychosis and behavioral disturbances in patients suffering from a broad range of disorders including schizophrenia.

Allosteric activators of mAChR show promise in achieving subtype selectivity

As discussed above, previous attempts to achieve selective activation of mAChRs with orthosteric ligands have failed. While there have been reports of achieving this in patent and primary literature, subsequent studies across multiple systems revealed that previously developed orthosteric agents are not truly selective. This phenomenon is sometimes attributed to an overestimation of mAChR selectivity resulting from artificial receptor-G protein coupling in recombinant cell lines.70 Furthermore, several compounds are chosen as selective agonists based on functional selectivity or selectivity based on efficacy rather than selective (bona fide) activation of individual mAChR subtypes. Because of this, a weak partial agonist at multiple mAChR subtypes may seem to be selective in cells lines where there is little or no receptor reserve but might have robust agonist activity at these same mAChR subtypes in vivo where high receptor reserves are common. As a result, these agents often activate multiple mAChR subtypes in animal models and humans.24,72 This apparent loss in subtype-selectivity upon evaluation in multiple systems was recently reported for the purported M1 agonist AF267B. AF267B was suggested to have selective agonist activity at M1 during its initial screening.44 However, when evaluated across multiple systems, AF267 was found to have off-target binding and activity at M3 and M5 receptor subtypes.47,72

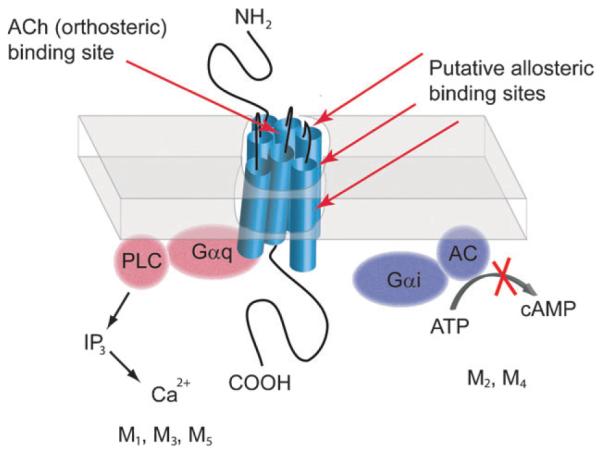

Previously developed orthosteric ligands have been designed to bind to mAChRs at amino acids that are highly conserved between M1–M5 mAChR subtypes. As a result, these ligands are unable to select for an individual mAChR subtype. Using an alternative approach, many academic and industrial laboratories are now screening for and developing compounds that bind these receptors at less conserved allosteric or ectopic binding sites that are topographically distinct from the orthosteric binding site (Fig. 1). These ligands, termed allosteric activators or modulators, provide excellent subtype-selectivity for individual subtypes of several GPCR families including metabotropic glutamate receptors, adenosine and serotonin receptors (for review see ref. 73 and 74). For muscarinic receptors, several allosteric compounds including both positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) and allosteric agonists of M1 and M4 receptors have been identified. PAMs are unable to activate receptors directly, but their binding is thought to modify receptor conformation which changes the binding and/or functional properties of orthosteric ligands for the targeted muscarinic receptor subtype. Because of these unique properties, these compounds may have theoretical advantages for treatment of various CNS disorders when compared to orthosteric agents in that they are inactive in the absence of neurotransmitter at a given synapse and only exert their effects in the presence of endogenous neurotransmitter. Thus, they maintain activity dependence in both temporal and spatial aspects of endogenous physiological signaling. The functional properties of a positive allosteric modulator can be seen in Fig. 2 where it elicits no response when added alone (A) but causes enhancement of the response to ACh resulting in a leftward shift in the concentration-response-curve of ACh (B). Allosteric agonists, on the other hand, do not require the presence of an endogenous ligand but activate mAChRs directly. This type of activation may prove advantageous for CNS disorders because these agonists could selectively drive activation of muscarinic receptors in neurons where presynaptic ACh release is attenuated due to degeneration of cholinergic inputs.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of concentration-response curves (CRC) of allosteric potentiators when added alone (A) or in the presence of an orthosteric agonist ACh (B). In (A), increasing concentrations of positive allosteric modulator (PAM) or orthosteric agonist are added and a functional response is measured. When added alone, the PAM has no effect whereas increasing concentrations of the orthosteric agonist induce a dose-dependent response. In (B), a single concentration of PAM or vehicle is added in the presence of increasing amounts of the orthosteric agonist ACh. A PAM shifts the agonist CRC to the left, resulting in an increase in ACh potency as depicted by the intersection of the descending lines to the x-axis.

For several years, agents with negative effects on affinity modulation for orthosteric compounds were the only types of allosteric agents for muscarinic receptors, a classic example being the inhibitory effect of gallamine.75–77 However, through subsequent studies by many laboratories, several compounds with positive effects on affinity of orthosteric ligands for receptors (PAMs), as well as direct allosteric agonists for muscarinic receptors, were identified. The first of these reported was brucine, an alkaloid isolated from Strychnos nux-vomica.78 Brucine is an allosteric potentiator at M1 receptors with a binding profile that is consistent with a ternary allosteric complex model in which both orthosteric and allosteric ligands bind receptors simultaneously and modify the affinities of each other. However, brucine induced a modest 2-fold increase in ACh affinity and required relatively high concentrations (micromolar) to elicit these effects. For these reasons, brucine is an unlikely candidate as an allosteric potentiator suitable for use in vivo.79 Regardless, brucine’s selectivity for M1 provides an important proof of concept that it is possible to develop agents with absolute selectivity for muscarinic subtypes.

After brucine, several subsequent studies led to the discovery of other allosteric modulators of mAChR subtypes. For example, thiochrome (2,7-dimethyl-5H-thiachromine-8-ethanol), an oxidation product and metabolite of thiamine, was reported as an M4 PAM, and SCH-202676 was shown to be a PAM at multiple GPCR subtypes including M1.80,81 In equilibrium binding assays, thiochrome had little or no effect on radiolabeled [3H]NMS binding at any mAChR. However, it inhibited [3H]NMS dissociation from M1 and M4 and increased the affinity of ACh three- to five-fold for inhibiting [3H]NMS binding at M4 while having little to no effect on ACh affinity at the other four mAChR subtypes.81 From these data, the authors concluded that the selective nature of thiochrome is due to selective cooperativity rather than selective binding.81

In addition to the discovery of early M1 and M4 PAMs, a major breakthrough in mAChR pharmacology came when Spalding et al. identified AC-42 (Structure B: Fig. S1‡) as the first in a novel class of compounds that bind to an allosteric site on the M1 receptor. Using a series of chimeric receptors, AC-42 was demonstrated to activate M1 receptors at an region of the receptor that is clearly distinct from the orthosteric ACh site and involves transmembrane domains one and seven82 (but not 3, 5, and 6 which contribute to the orthosteric site83–85). This region of the receptor is not conserved among mAChR subtypes likely explaining its unprecedented selectivity. Subsequent studies monitoring intracellular calcium release and inositolphosphate accumulation confirmed that AC-42 was active in cell lines; however, the in vivo use of AC-42 has remained in question.70 In addition to AC-42, the biologically active metabolite of the atypical antipsychotic clozapine, N-desmethylclozapine (NDMC) was also shown have antagonistic properties at M1 mAChRs.86 NDMC is highly selective for M1 relative to other mAChR subtypes and activates M1 receptors containing a mutation in the orthosteric binding site. Furthermore, NDMC potentiates NMDA receptor activity, crosses the blood–brain barrier, and induces c-fos expression in rat forebrain suggesting that it may contribute to the unique therapeutic profile of clozapine via selective activation of M1.86–88

These discoveries have broad implications for our understanding of muscarinic receptor structure and function as they suggest that allosteric agents activate M1 and M4 mAChRs with a high degree of subtype selectivity. However, previously developed mAChR allosteric agonists and PAMs such as brucine do not have the pharmacological profiles and physicochemical properties required to be useful tools to assess the effects of allosteric activation in more complex native systems. For example, many of the earlier agents have substantial off-target activities and have poor solubility in physiological buffer systems, preventing their use in vivo. Furthermore, compounds such as AC-42 failed to activate M1 receptors in native tissue systems such as brain slices.70 For these reasons, many industrial and academic laboratories are now developing newer allosteric molecules that have the required properties such as true subtype selectivity, favorable pharmacokinetic profiles, and CNS penetration.

Advances in the development of novel selective activators of M1

Over the past few years, several novel selective M1 agonists and allosteric potentiators have been identified. These compounds are providing important new tools to evaluate the potential utility of selective activators of M1 for treatment of AD and other CNS disorders. For instance, TBPB,72 77-LH-28-1,70,89 and AC-26058490–92 (Structure E, C, and D; see Fig. S1‡) have been reported as agonists of M1. These compounds provide an exciting new approach for developing therapeutic agents to selectively activate M1. In addition, they provide new tools that can be used to determine the physiological roles of M1 in the central nervous system and test the hypotheses that activation of M1 has effects that would predict antipsychotic efficacy or cognitive enhancements in humans. All compounds are systemically active and are proving to be useful for in vivo studies of M1 activation.

TBPB selectively activates M1 in cell lines and has no agonist activity at any other mAChR subtypes. Mutations that reduce the activity of orthosteric agonists have no effect on the response to TBPB, and Schild analysis of the blockade of TBPB effects with the orthosteric antagonist atropine revealed that TBPB does not interact with the orthosteric site in a competitive manner. These data are consistent with the predictions of an allosteric ternary complex model for the actions of two molecules that interact with distinct sites73,93 and are consistent with the hypothesis that TBPB acts as an allosteric M1 agonist. Interestingly, TBPB induces M1-dependent potentiation of NMDA currents in hippocampal pyramidal cells, an action that is thought to be important for the cognition-enhancing effects of mAChR activation. By contrast, TBPB does not reduce inhibitory or excitatory synaptic transmission at the Schaffer Collateral-CA1 synapse, effects thought to be mediated by M2 and M4 mAChRs, respectively.72 Of particular relevance to AD pathology, early studies in cell lines indicated that TBPB induces a shift in processing of APP towards the non-amyloidogenic pathway and decreases Aβ production in vitro.72 This is consistent with previously discussed studies indicating that mAChR activation has favorable effects on APP processing in animal models and in humans94–96 and provides further support for the hypothesis that selective activation of M1 might have disease-modifying potential in the treatment of AD. TBPB is also systemically active and crosses the blood–brain barrier, making this a useful tool for studies of the possible cognition-enhancing effects of M1-selective agonists. These encouraging results provide strong support for the utility of M1 allosteric agonists in activating this crucial mAChR subtype in the CNS without inducing the adverse effects associated with less selective mAChR agonists.

A second systemically active M1 agonist, 77-LH-28-1, was discovered as a structural analog of AC-42.70,89 77-LH-28-1 is selective for M1 relative to M2, M4, and M5 subtypes but also has weak agonist activity at M3 at higher concentrations. Interestingly, in contrast to the effects of atropine on the response to TBPB, the orthosteric antagonist scopolamine induces parallel rightward shifts in the 77-LH-28-1 concentration response curve (CRC) suggesting that 77-LH-28-1 may bind the orthosteric site of M1.70 However, extensive mutagenesis studies combined with functional studies and analysis of the effects of 77-LH-28-1 on binding of an orthosteric antagonist are consistent with an allosteric mode of agonist action of this compound. Together, these studies raise the possibility that 77-LH-28-1 might be what has been referred to as a ‘bi-topic’ ligand that binds to a site that overlaps with the orthosteric site but also includes an allosteric site that modulates orthosteric site affinity.97 Electrophysiological studies indicate that 77-LH-28-1 increases activity of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells in vitro and in vivo and induces synchronous network activity in the hippocampus.70 Interestingly, unlike the orthosteric agonist oxotremorine, which activates Gαs, Gαi, and Gαq G proteins, 77-LH-28-1 selectively activates the coupling of M1 to Gαq and Gαs signaling without activating coupling to Gαi;89 this indicates that 77-LH-28-1 differentially activates distinct M1-mediated responses. Such differential effects of allosteric agonists on various responses to M1 activation could prove to be crucially important in determining the in vivo and ultimately therapeutic potential of allosteric M1 agonists.

An additional structural analog of AC-42, AC-260584 was also recently reported as an orally bioavailable M1 allosteric agonist with antipsychotic and cognitive enhancing effects.90,98 Acute systemic administration of AC-260584 significantly reversed amphetamine and MK-801-induced hyperlocomotion and apomorphine-induced climbing, two animal models predictive of antipsychotic efficacy. Additionally, AC-260584 did not affect spontaneous locomotor activity or step down latency and produced no stereotypic behaviors, sedation, or ataxia in the dose ranges tested in mice and rats. Furthermore, administration of AC-260584 did not induce catalepsy in rats suggesting it has a lesser liability for causing extrapyramidal motor side-effects when compared to typical antipsychotics, as catatonic induction in rats has been shown to predict these effects in humans.98,99 Interestingly, AC-260584 also improved the performance of mice in the Morris water maze, a measure of hippocampal-dependent spatial memory. Together, these initial data suggest that M1 activation may attenuate dopaminergic hyperfunction and dopamine mediated behavioral disturbances and that the M1 receptor likely plays a role in hippocampal-mediated memory. More recent studies revealed that subcutaneous administration of AC-260584 induced ERK1/2 activation in the CA1 area of mouse hippocampus, an effect that was absent in M1 knockout mice.90 Furthermore, AC-260584 administration improved visual recognition memory in mice in the novel object recognition paradigm further supporting pro-cognitive effects of M1 activation. While these data provide advancements in the development of bioavailable muscarinic agonists, the lack of true mAChR subtype selectivity90 of AC-260584 and related compounds may limit their use as antipsychotic/pro-cognitive agents.

An exciting development in the field of muscarinic pharmacology has been the recent discovery of M1 allosteric agonists VU0184670 and VU0357017100 (Structure F and G; Fig. S1‡). These compounds are chemically optimized analogs of M1 allosteric agonists identified in a primary high-throughput screen in the Vanderbilt Screening Center for GPCRs, Ion Channels and Transporters, initiated and supported by the NIH Molecular Libraries Roadmap. A diversity-oriented synthesis/iterative screening approach was used to rapidly explore structure–activity relationships (SAR) of novel compounds with the goal being to improve potency while maintaining subtype selectivity. Neither VU0184670 nor VU0357017 displayed any agonist or antagonist activity at M2–M5, and these allosteric agonists also possessed an exceptionally clean ancillary pharmacology profile when assessed in a screen of sixty-eight GPCRs, ion channels, and transporter targets.100 Thus, these newer generation M1 allosteric agonists represent a major breakthrough and are much more highly selective; they also have improved physicochemical properties compared to previous allosteric or orthosteric M1 agonists. Mutagenesis studies revealed that residues located in the extracellular loop three (o3) and the first helical turn of transmembrane seven (TM7) of the M1 receptor were critical for activity of VU0184670. This same region of M4 was also implicated in the actions of M4 PAM LY2033298.101 Both M1 allosteric agonists lead compounds were found to possess a high degree of solubility in aqueous solutions and were centrally penetrant after systemic administration with VU0184670 possessing a superior pharmacokinetic profile. Similar to what was found with TBPB, VU0184670 also potentiates NMDAR currents evoked by NMDA application in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Excitingly, acute i.p. administration of VU0357017 reversed cognitive deficits induced by the orthosteric mAChR antagonist scopolamine in a contextual fear conditioning paradigm, a measure of hippocampal dependent learning.100

In addition to the discovery of novel M1-selective allosteric agonists, much progress has been made in the discovery of novel M1 PAMs that act as allosteric potentiators of this receptor. For instance, multiple M1 allosteric potentiators have recently been identified in a high-throughput functional-screening campaign.102 These molecules belong to several structurally distinct chemical scaffolds and include compounds that are selective for M1 relative to other mAChR subtypes. None of the compounds identified had agonist activity; each behaved as a pure PAM and induced parallel leftward shifts in the ACh CRC. Furthermore, none of the newer M1 PAMs compete for binding at the orthosteric ACh-binding site. The two most selective compounds, VU0029767 and VU0090157 (Structure A and B; Fig. S2‡), were studied in detail and induced dose-dependent shifts in ACh affinity at M1 that are consistent with their effects in functional assays; this indicates that they mechanistically enhance M1 activity by increasing ACh affinity. However, these compounds were strikingly different in their ability to potentiate responses at a mutant M1 receptor that exhibits decreased affinity for ACh and in their ability to affect responses to the allosteric M1 agonist TBPB. Furthermore, VU0090157 induced similar potentiation of M1 activation of PLC and PLD activity, whereas VU0029767 potentiated activation of PLC but not PLD signaling. These data provide additional examples of an allosteric compounds inducing differential coupling of M1 to distinct signaling pathways.

In a recent publication, researchers reported the discovery of benzyl quinolone carboxylic acid (BQCA) (Structure C; Fig. S2‡) as a highly selective and efficacious allosteric potentiator of M1.103 Like the previously described M1 PAMs VU0090157 and VU0029767, BQCA had no direct agonist activity but induced a robust leftward shift in ACh’s concentration-response curve. BQCA had no activity at M2, M3, M4, or M5. Using in situ hybridization, the authors also showed that BQCA substantially increased two markers of neuronal activation, c-fos and arc, in multiple brain regions including cortex of wild type, but not M1 knockout mice. Furthermore, BQCA did not compete for orthosteric [3H]-NMS binding but increased affinity of M1 for ACh. Residues Y179 and W400 which lie in the second (o2) and third (o3) extracellular loop of the receptor were shown to be required for the potentiation of M1 by BQCA as mutations of these residues completely eliminated potentiation. Interestingly, BQCA was shown to be systemically active and fully reversed the cognitive impairment induced by scopolamine in a contextual fear-conditioning model of episodic-like memory.103 In addition, BQCA induced changes in electroencephalography oscillations in a manner that is consistent with a potential cognition-enhancing effect. These findings provide exciting new data in support of the hypothesis that it will be possible to develop highly selective M1 PAMs that have cognition-enhancing effects in vivo.

Shirey et al.,104 also extensively characterized the M1 PAM BQCA and confirmed that this compound is highly selective for M1 relative to other mAChR subtypes as well as to a panel of other GPCRs.104 Since previous studies in M1 knockout mice supported a role for this receptor in cognitive behaviors requiring normal functioning of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Anagnostaras et al.57), we sought to examine the effect of selective M1 activation in mPFC pyramidal cells. In these cells, carbachol (CCh) induced robust inward currents, an effect that was potentiated by BQCA.104 BQCA also potentiated CCh-induced increases in excitatory drive to these cells as seen by an increase in spontaneous EPSCs. Furthermore, systemic administration of BQCA drastically increased the firing rate of mPFC pyramidal cells in vivo in multichannel single unit recordings and reversed impairments in PFC-dependent learning in a mouse model of AD.104 Together, these studies support a pivotal role for the M1 receptor in modulating PFC-dependent learning and suggest that this mAChR subtype represents an exciting potential therapeutic target for the treatment of CNS disorders characterized by memory and cognitive impairment.

BQCA was also recently optimized to yield a M1-selective allosteric potentiator with improved potency and increased free fraction. Using an analog library synthesis approach, Yang et al.105 showed that modifications to BQCA’s quinolone core and N1-benzyl substituent yielded multiple compounds with potencies that were less than 100 nM while retaining greater than 5% free fraction. Later studies showed that the incorporation of pyridines and diazines into the biphenyl region of BQCA led to lower plasma protein binding.106 Also, the addition of a C-ring pyrazole increased CNS exposure and improved performance in a mouse contextual fear conditioning assay.107 Together, these studies suggest an optimized version of BQCA with possible improvements in its cognition-enhancing effects via increased CNS exposure.

In addition to M1-selective allosteric agonists and PAMs, another major breakthrough in mAChR pharmacology came with the discovery of the novel highly selective allosteric potentiator of M4, LY2033298101 (Structure D; Fig. S2‡). Like the previously described M1 PAMs, LY2033298 does not activate mAChRs directly but induces robust potentiation of ACh responses. It also showed exquisite selectivity at M4 receptors with no discernable activity at the other mAChR subtypes. Site-directed mutagenesis studies revealed that residue D432 in the third extracellular loop (o3) of the receptor is involved in the potentiating effects of LY2033298. When co-administered with a low dose (0.1–0.3 mg kg−1) of oxotremorine, LY2033298 attenuated conditioned avoidance responding (CAR) and reversed apomorphine-induced disruption of the prepulse inhibition (PPI) of the acoustic startle response. Potentiation of M4 also augmented oxotremorine-stimulated dopamine (DA) release in dialysate from prefrontal cortex but not nucleus accumbens supporting a role for M4 in modulating mesocortical but not mesolimbic DA levels. However, when compared to experiments performed using human M4 AChRs (hM4) membranes, the potency of LY2033298 for [3H]-oxotremorine-M potentiation in rat M4 AChRs (rM4) membranes was diminished 5- to 6-fold. This species difference was postulated to be responsible for LY2033298’s inability to induce responses in rats when administered alone in CAR, PPI, and DA release assays.101 The efficacy of LY2033298 in rodent models and on DA release provided evidence that allosteric potentiation of M4 is a viable approach for the development of muscarinic-based antipsychotic agents.

Our laboratory employed a chemoinformatic and medicinal chemistry-based approach to identify a new series of ligands that interacts with an allosteric site on M4. Like LY2033298, compounds identified in these studies selectively potentiated M4 responses to ACh.108 Their binding profile supported an allosteric mode of action, as none of these ligands displaced [3H]-NMS in equilibrium binding assays. The lead compound in this series, VU100010 (Structure E; Fig. S2‡), possessed an EC50 for potentiation of 400 nM and shifted the functional ACh response curve 47-fold to the left. As described in Shirey et al.,108 binding studies indicated that VU100010 exerted its allosteric potentiation of M4 by increasing the affinity of the receptor for ACh and by increasing downstream coupling of M4 to G proteins. Electrophysiological studies revealed that VU100010 modulated hippocampal synaptic transmission at excitatory but not inhibitory CA1 synapses in acute slices.108

Despite this notable advance in mAChR pharmacology, VU100010 suffered from poor physicochemical properties (log P ~ 4.5) and in vivo studies proved infeasible because VU100010 could not be formulated into a homogeneous solution in any acceptable vehicle. For these reasons, subsequent efforts focused on the development of novel CNS-penetrant analogs of VU100010.109 Of these, VU0152099 and VU0152100 (Structure F and G; Fig. S2‡) were identified as M4 PAMS with EC50 values for potentiation of ACh responses of approximately 400 nM. These novel modulators maintained a high degree of mAChR subtype selectivity when compared to VU100010 and also showed functional selectivity in a screen of 15 other GPCRs that are highly expressed in the CNS. Similar to the binding profile of VU100010, VU0152099 and VU0152100 did not compete for orthosteric [3H]-NMS binding but increased M4 receptor affinity for ACh. The most exciting finding in this series of studies was that VU0152099 and VU0152100 exhibited improved physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties as compared to VU100010; in contrast to the high log P of VU100010 (4.5), both VU0152099 and VU0152100 possessed log P values of 3.65 and 3.6, respectively, a full order of magnitude less lipophilic than VU100010. As a consequence, both VU0152099 and VU0152100 afforded homogeneous dosing solutions in multiple vehicles acceptable for in vivo studies. Furthermore, both compounds exhibited substantial systemic absorption and brain penetration after systemic dosing. Subsequent studies in an animal model used to predict antipsychotic efficacy showed that both novel M4 PAMS reversed amphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion.109 It will be of critical importance to further evaluate these compounds and their efficacy in other animal models of psychosis and cognition to yield a deeper understanding of the role of this receptor subtype in human diseases like schizophrenia and AD.

Lastly, it is important to note that, at present, the mechanisms underlying the selective nature of allosteric agents for M1 and M4 mAChRs are not fully established. As previously discussed, the initial rationale driving this approach was that allosteric ligands bind to evolutionarily less-conserved allosteric sites on the M1 or M4 receptors, as opposed to the highly conserved orthosteric (ACh) binding site and might, therefore, bind selectively to allosteric sites on individual mAChR subtypes. This hypothesis has been clearly established for metabotropic glutamate receptors where selective binding of allosteric ligands to individual subtypes has been established as the basis for the selectivity of some ligands.73 However, this does not rule out the possibility that these compounds bind to allosteric sites on multiple mAChR subtypes with similar affinities but that selectivity is conferred by selective cooperativity with orthosteric-site agonists,73,93 as has been suggested for selective PAM activity of thiochrome at M4.81 If this is the case, it is possible that selectivity of these compounds will vary depending on the system in which their effects are measured. Thus, it will be crucial to develop a clear understanding of the molecular basis for the observed selectivity in future studies. Optimally, this should be addressed with radioligands that act at the allosteric but not the orthosteric sites. However, studies involving detailed analysis of effects of allosteric compounds on binding of orthosteric-site ligands in addition to mutagenesis studies will also shed light on this important issue. Finally, it will be critical to understand whether selectivity of PAMs holds constant in the presence of multiple different classes of orthosteric agonists; examples of probe dependence of allosteric modulators are now surfacing.110 Preliminary findings by our group and others with the M4 PAM LY2033298 and related analogs suggest that selectivity of these compounds across mAChR subtypes exists in the presence of ACh but not another orthosteric agonist, oxotremorine. Considering that co-administration of low doses of systemically active muscarinic agonists may be required to see efficacy of PAMs in different behavioral models, it will be critical to explore selectivity profiles of allosteric modulators not only in careful radioligand binding experiments but also in multiple functional assays in vitro with different classes of orthosteric agonists.

Conclusions

Exciting new data from pre-clinical and clinical studies suggest that selective M1 or M4 mAChR activation might provide a novel approach to the treatment of multiple CNS disorders. This includes compelling evidence that selective increases in the activity of M1 and M4 could provide a novel approach to the treatment of AD and schizophrenia and perhaps have efficacy in treating psychosis and cognitive impairment in other neurodegenerative diseases. Major advances have been made in developing selective allosteric agonists and PAMs of both M1 and M4 as an alternative approach for the development of selective receptor activators. These molecules have now been optimized for use in animal models, and early studies indicate that they have effects in animal models that predict efficacy in the treatment of these disorders. In addition to potential clinical utility of selective mAChR activators, abundant clinical and animal studies indicate that highly selective antagonists of specific mAChR subtypes might have utility in the treatment of other CNS disorders including dystonia, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy and others.24,42,47,111–115 In each case, subtype selectivity will be a key to achieving clinical efficacy in the absence of adverse effects. For other GPCRs, it has been possible to discover allosteric modulators that serve as potentiators or inhibitors (i.e. NAMs) of receptor function.116–118 Thus, it might be possible to discover selective allosteric antagonists of mAChR subtypes. Indeed, a recent high-throughput screening campaign that focused on M1 PAMs was successful in identifying NAMs of mAChR subtypes that are still under development.102 These exciting advances are providing a fundamental advance in our approach to modulating mAChRs as drug targets and may provide a novel approach to treatment of AD and schizophrenia in addition to other CNS disorders.

Supplementary Material

Biography

Gregory J. Digby completed his PhD in 2008 in the Department of Pharmacology, Medical College of Georgia, supervised by Dr Nevin Lambert. He is currently a postdoctoral research fellow at Vanderbilt University in Dr Jeff Conn’s laboratory.

Jana K. Shirey completed her PhD in 2009 in the Department of Pharmacology, Vanderbilt University, supervised by Dr Jeff Conn. She is currently a postdoctoral research fellow at Vanderbilt University in Dr Maureen Hahn’s laboratory.

Dr Jeff Conn is the Lee E. Limbird Professor of Pharmacology at Vanderbilt University. He is also the director of the Vanderbilt Program in Drug Discovery. Dr Conn’s research involves developing a detailed understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in regulating chemical and electrical signaling in the central nervous system. He is especially interested in understanding how signaling is regulated in indentified neuronal circuits that are important for human neurological and psychiatric disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia. His work employs a broad range of techniques including electrophysiology, biochemistry, behavior, high throughput screening (HTS), and medicinal chemistry of novel small molecule therapeutics to aid in validating novel therapeutic approaches and in understanding the biology of signaling in the central nervous system.

Footnotes

This article is part of a Molecular BioSystems themed issue on Chemical Genomics.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Supplementary figures of structures (Fig. S1 and S2). See DOI: 10.1039/c002938f

Notes and references

- 1.Jones EG, Burton H, Saper CB, Swanson LW. J. Comp. Neurol. 1976;167:385–419. doi: 10.1002/cne.901670402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kievit J, Kuypers HG. Science. 1975;187:660–662. doi: 10.1126/science.1114317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segal M, Landis S. Brain Res. 1974;78:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitehouse PJ, Price DL, Struble RG, Clark AW, Coyle JT, Delon MR. Science. 1982;215:1237–1239. doi: 10.1126/science.7058341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baxter MG, Chiba AA. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1999;9:178–183. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)80024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mesulam MM, Mufson EJ, Wainer BH, Levey AI. Neuroscience. 1983;10:1185–1201. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fibiger HC, Damsma G, Day JC. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1991;295:399–414. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-0145-6_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston MV, McKinney M, Coyle JT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1979;76:5392–5396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coyle JT, Price DL, DeLong MR. Science. 1983;219:1184–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.6338589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dekker AJ, Connor DJ, Thal LJ. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1991;15:299–317. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunnett SB. Psychopharmacology. 1985;87:357–363. doi: 10.1007/BF00432721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehmann J, Nagy JI, Atmadia S, Fibiger HC. Neuroscience. 1980;5:1161–1174. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(80)90195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voytko M, Olton D, Richardson R, Gorman L, Tobin J, Price D. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:167–186. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00167.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGaughy J, Kaiser T, Sarter M. Behav. Neurosci. 1996;110:247–265. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasselmo ME. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2006;16:710–715. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damasio AR, Graff-Radford NR, Eslinger PJ, Damasio H, Kassell N. Arch. Neurol. 1985;42:263–271. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060030081013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drachman DA, Leavitt J. Arch. Neurol. 1974;30:113–121. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1974.00490320001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartus RT, Dean RL, 3rd, Beer B, Lippa AS. Science. 1982;217:408–414. doi: 10.1126/science.7046051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salah-Uddin H, Scarr E, Pavey G, Harris K, Hagan JJ, Dean B, Challiss RA, Watson JM. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2156–2166. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crook JM, Tomaskovic-Crook E, Copolov DL, Dean B. Biol. Psychiatry. 2000;48:381–388. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00918-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crook JM, Tomaskovic-Crook E, Copolov DL, Dean B. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:918–925. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dean B, McLeod M, Keriakous D, McKenzie J, Scarr E. Mol. Psychiatry. 2002;7:1083–1091. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barten DM, Albright CF. Mol. Neurobiol. 2008;37:171–186. doi: 10.1007/s12035-008-8031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conn PJ, Jones CK, Lindsley CW. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009;30:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonner TI, Buckley NJ, Young AC, Brann MR. Science. 1987;237:527–532. doi: 10.1126/science.3037705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonner TI, Young AC, Brann MR, Buckley NJ. Neuron. 1988;1:403–410. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caufield PW, Cutter GR, Dasanayake AP. J. Dent. Res. 1993;72:37–45. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peralta EG, Ashkenazi A, Winslow JW, Smith DH, Ramachandran J, Capon DJ. EMBO J. 1987;6:3923–3929. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caulfield MP. Pharmacol. Ther. 1993;58:319–379. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90027-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hulme EC, Lu ZL, Bee MS. Recept. Channels. 2003;9:215–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levey AI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:13541–13546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levey AI, Edmunds SM, Koliatsos V, Wiley RG, Heilman CJ. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:4077–4092. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-04077.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levey AI, Kitt CA, Simonds WF, Price DL, Brann MR. J. Neurosci. 1991;11:3218–3226. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03218.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hersch SM, Gutekunst CA, Rees HD, Heilman CJ, Levey AI. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:3351–3363. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03351.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mrzljak L, Levey AI, Goldman-Rakic PS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:5194–5198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Alzheimer’s Dementia. 2007;3:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muir JL. Pharmacol., Biochem. Behav. 1997;56:687–696. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00431-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies P, Maloney AJ. Lancet. 1976;308:1403. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91936-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perry EK, Perry RH, Blessed G, Tomlinson BE. Lancet. 1977;309:189. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91780-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitehouse PJ, Price DL, Clark AW, Coyle JT, DeLong MR. Ann. Neurol. 1981;10:122–126. doi: 10.1002/ana.410100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang Y, Mishkin M, Aigner TG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:12667–12669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wess J, Eglen RM, Gautam D. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2007;6:721–733. doi: 10.1038/nrd2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Auld DS, Kornecook TJ, Bastianetto S, Quirion R. Prog. Neurobiol. 2002;68:209–245. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caccamo A, Oddo S, Billings LM, Green KN, Martinez-Coria H, Fisher A, LaFerla FM. Neuron. 2006;49:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fisher A, Pittel Z, Haring R, Bar-Ner N, Kliger-Spatz M, Natan N, Egozi I, Sonego H, Marcovitch I, Brandeis R. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2003;20:349–356. doi: 10.1385/JMN:20:3:349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Messer WS., Jr. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002;2:353–358. doi: 10.2174/1568026024607553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langmead CJ, Watson J, Reavill C. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;117:232–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buxbaum JD, Oishi M, Chen HI, Pinkas-Kramarski R, Jaffe EA, Gandy SE, Greengard P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:10075–10078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eckols K, Bymaster FP, Mitch CH, Shannon HE, Ward JS, DeLapp NW. Life Sci. 1995;57:1183–1190. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)02064-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haring R, Gurwitz D, Barg J, Pinkas-Kramarski R, Heldman E, Pittel Z, Wengier A, Meshulam H, Marciano D, Karton Y, Fisher A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;203:652–658. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muller DM, Mendla K, Farber SA, Nitsch RM. Life Sci. 1997;60:985–991. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nitsch RM, Slack BE, Wurtman RJ, Growdon JH. Science. 1992;258:304–307. doi: 10.1126/science.1411529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Forlenza OV, Spink JM, Dayanandan R, Anderton BH, Olesen OF, Lovestone S. J. Neural Transm. 2000;107:1201–1212. doi: 10.1007/s007020070034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berkeley JL, Gomeza J, Wess J, Hamilton SE, Nathanson NM, Levey AI. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2001;18:512–524. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hamilton SE, Nathanson NM. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:15850–15853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011563200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marino MJ, Rouse ST, Levey AI, Potter LT, Conn PJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:11465–11470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anagnostaras SG, Murphy GG, Hamilton SE, Mitchell SL, Rahnama NP, Nathanson NM, Silva AJ. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:51–58. doi: 10.1038/nn992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miyakawa T, Yamada M, Duttaroy A, Wess J. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5239–5250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05239.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gerber DJ, Sotnikova TD, Gainetdinov RR, Huang SY, Caron MG, Tonegawa S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:15312–15317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261583798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bartolomeo AC, Morris H, Buccafusco JJ, Kille N, Rosenzweig-Lipson S, Husbands MG, Sabb AL, Abou-Gharbia M, Moyer JA, Boast CA. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;292:584–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fisher A, Heldman E, Gurwitz D, Haring R, Karton Y, Meshulam H, Pittel Z, Marciano D, Brandeis R, Sadot E, Barg Y, Pinkas-Kramarski R, Vogel Z, Ginzburg I, Treves TA, Verchovsky R, Klimowsky S, Korczyn AD. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1996;777:189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb34418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Loudon JM, Bromidge SM, Brown F, Clark MS, Hatcher JP, Hawkins J, Riley GJ, Noy G, Orlek BS. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;283:1059–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raedler TJ, Bymaster FP, Tandon R, Copolov D, Dean B. Mol. Psychiatry. 2007;12:232–246. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raedler TJ, Knable MB, Jones DW, Urbina RA, Gorey JG, Lee KS, Egan MF, Coppola R, Weinberger DR. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2003;160:118–127. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thomsen M, Wess J, Fulton BS, Fink-Jensen A, Caine SB. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208:401–416. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1740-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bodick NC, Offen WW, Levey AI, Cutler NR, Gauthier SG, Satlin A, Shannon HE, Tollefson GD, Rasmussen K, Bymaster FP, Hurley DJ, Potter WZ, Paul SM. Arch. Neurol. 1997;54:465–473. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550160091022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bodick NC, Offen WW, Shannon HE, Satterwhite J, Lucas R, van Lier R, Paul SM. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 1997;11(Suppl 4):S16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shekhar A, Potter WZ, Lightfoot J, Lienemann J, Dube S, Mallinckrodt C, Bymaster FP, McKinzie DL, Felder CC. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165:1033–1039. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.06091591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jakubik J, El-Fakahany EE, Dolezal V. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;70:656–666. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Langmead CJ, Austin NE, Branch CL, Brown JT, Buchanan KA, Davies CH, Forbes IT, Fry VA, Hagan JJ, Herdon HJ, Jones GA, Jeggo R, Kew JN, Mazzali A, Melarange R, Patel N, Pardoe J, Randall AD, Roberts C, Roopun A, Starr KR, Teriakidis A, Wood MD, Whittington M, Wu Z, Watson J. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008;154:1104–1115. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Noetzel MJ, Grant MK, El-Fakahany EE. Pharmacology. 2009;83:301–317. doi: 10.1159/000214843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jones CK, Brady AE, Davis AA, Xiang Z, Bubser M, Tantawy MN, Kane AS, Bridges TM, Kennedy JP, Bradley SR, Peterson TE, Ansari MS, Baldwin RM, Kessler RM, Deutch AY, Lah JJ, Levey AI, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:10422–10433. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1850-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Conn PJ, Christopoulos A, Lindsley CW. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2009;8:41–54. doi: 10.1038/nrd2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.May LT, Christopoulos A. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2003;3:551–556. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(03)00107-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clark AL, Mitchelson F. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1976;58:323–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1976.tb07708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nedoma J, Dorofeeva NA, Tucek S, Shelkovnikov SA, Danilov AF. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1985;329:176–181. doi: 10.1007/BF00501209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stockton JM, Birdsall NJ, Burgen AS, Hulme EC. Mol. Pharmacol. 1983;23:551–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lazareno S, Gharagozloo P, Kuonen D, Popham A, Birdsall NJ. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998;53:573–589. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jakubik J, Bacakova L, El-Fakahany EE, Tucek S. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:172–179. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.1.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fawzi AB, Macdonald D, Benbow LL, Smith-Torhan A, Zhang H, Weig BC, Ho G, Tulshian D, Linder ME, Graziano MP. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;59:30–37. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lazareno S, Dolezal V, Popham A, Birdsall NJ. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;65:257–266. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Spalding TA, Trotter C, Skjaerbaek N, Messier TL, Currier EA, Burstein ES, Li D, Hacksell U, Brann MR. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;61:1297–1302. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.6.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Allman K, Page KM, Curtis CA, Hulme EC. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;58:175–184. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Spalding TA, Birdsall NJ, Curtis CA, Hulme EC. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:4092–4097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ward SD, Curtis CA, Hulme EC. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:1031–1041. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.5.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sur C, Mallorga PJ, Wittmann M, Jacobson MA, Pascarella D, Williams JB, Brandish PE, Pettibone DJ, Scolnick EM, Conn PJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:13674–13679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1835612100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Baldessarini RJ, Centorrino F, Flood JG, Volpicelli SA, Huston-Lyons D, Cohen BM. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;9:117–124. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Young CD, Meltzer HY, Deutch AY. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1998;19:99–103. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(97)00203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Thomas RL, Mistry R, Langmead CJ, Wood MD, Challiss RA. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;327:365–374. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.141788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bradley SR, Lameh J, Ohrmund L, Son T, Bajpai A, Nguyen D, Friberg M, Burstein ES, Spalding TA, Ott TR, Schiffer HH, Tabatabaei A, McFarland K, Davis RE, Bonhaus DW. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li Z, Bonhaus DW, Huang M, Prus AJ, Dai J, Meltzer HY. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007;572:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Spalding TA, Ma JN, Ott TR, Friberg M, Bajpai A, Bradley SR, Davis RE, Brann MR, Burstein ES. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;70:1974–1983. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.024901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.May LT, Leach K, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007;47:1–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Caccamo A, Fisher A, LaFerla FM. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2009;6:112–117. doi: 10.2174/156720509787602915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fisher A. Neurodegener. Dis. 2008;5:237–240. doi: 10.1159/000113712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nitsch RM, Deng M, Tennis M, Schoenfeld D, Growdon JH. Ann. Neurol. 2000;48:913–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lebon G, Langmead CJ, Tehan BG, Hulme EC. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009;75:331–341. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vanover KE, Veinbergs I, Davis RE. Behav. Neurosci. 2008;122:570–575. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hoffman DC, Donovan H. Psychopharmacology. 1995;120:128–133. doi: 10.1007/BF02246184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lebois EP, Bridges TM, Lewis LM, Dawson ES, Kane AS, Xiang Z, Jadhav S, Yin H, Kennedy JP, Meiler J, Niswender CM, Jones CK, Conn PJ, Weaver CD, Lindsley CW. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2010;1:104–121. doi: 10.1021/cn900003h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chan WY, McKinzie DL, Bose S, Mitchell SN, Witkin JM, Thompson RC, Christopoulos A, Lazareno S, Birdsall NJ, Bymaster FP, Felder CC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:10978–10983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800567105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Marlo JE, Niswender CM, Days EL, Bridges TM, Xiang Y, Rodriguez AL, Shirey JK, Brady AE, Nalywajko T, Luo Q, Austin CA, Williams MB, Kim K, Williams R, Orton D, Brown HA, Lindsley CW, Weaver CD, Conn PJ. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009;75:577–588. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.052886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ma L, Seager M, Wittmann M, Jacobson M, Bickel D, Burno M, Jones K, Graufelds VK, Xu G, Pearson M, McCampbell A, Gaspar R, Shughrue P, Danziger A, Regan C, Flick R, Pascarella D, Garson S, Doran S, Kreatsoulas C, Veng L, Lindsley CW, Shipe W, Kuduk S, Sur C, Kinney G, Seabrook GR, Ray WJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:15950–15955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900903106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shirey JK, Brady AE, Jones PJ, Davis AA, Bridges TM, Kennedy JP, Jadhav SB, Menon UN, Xiang Z, Watson ML, Christian EP, Doherty JJ, Quirk MC, Snyder DH, Lah JJ, Levey AI, Nicolle MM, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:14271–14286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3930-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yang FV, Shipe WD, Bunda JL, Nolt MB, Wisnoski DD, Zhao Z, Barrow JC, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittmann M, Seager MA, Koeplinger KA, Hartman GD, Lindsley CW. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:531–536. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.11.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kuduk SD, Di Marco CN, Cofre V, Pitts DR, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittmann M, Seager M, Koeplinger K, Thompson CD, Hartman GD, Bilodeau MT. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:657–661. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kuduk SD, Di Marco CN, Cofre V, Pitts DR, Ray WJ, Ma L, Wittmann M, Veng L, Seager M, Koeplinger K, Thompson CD, Hartman GD, Bilodeau MT. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:1334–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shirey JK, Xiang Z, Orton D, Brady AE, Johnson KA, Williams R, Ayala JE, Rodriguez AL, Wess J, Weaver D, Niswender CM, Conn PJ. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:42–50. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Brady AE, Jones CK, Bridges TM, Kennedy JP, Thompson AD, Heiman JU, Breininger ML, Gentry PR, Yin H, Jadhav SB, Shirey JK, Conn PJ, Lindsley CW. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;327:941–953. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.140350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kenakin T. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screening. 2008;11:337–343. doi: 10.2174/138620708784534824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fisher A. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bymaster FP, Carter PA, Yamada M, Gomeza J, Wess J, Hamilton SE, Nathanson NM, McKinzie DL, Felder CC. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;17:1403–1410. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bymaster FP, Felder C, Ahmed S, McKinzie D. Curr. Drug Targets: CNS Neurol. Disord. 2002;1:163–181. doi: 10.2174/1568007024606249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bymaster FP, Felder CC, Tzavara E, Nomikos GG, Calligaro DO, McKinzie DL. Progress NeuroPsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;27:1125–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Katzenschlager R, Sampaio C, Costa J, Lees A. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2003 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003735. CD003735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gasparini F, Lingenhohl K, Stoehr N, Flor PJ, Heinrich M, Vranesic I, Biollaz M, Allgeier H, Heckendorn R, Urwyler S, Varney MA, Johnson EC, Hess SD, Rao SP, Sacaan AI, Santori EM, Velicelebi G, Kuhn R. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1493–1503. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Campbell UC, Lalwani K, Hernandez L, Kinney GG, Conn PJ, Bristow LJ. Psychopharmacology. 2004;175:310–318. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mannaioni G, Marino MJ, Valenti O, Traynelis SF, Conn PJ. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5925–5934. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05925.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.