Abstract

Objectives

To assess pregnancies that could have been averted through improved access to contraceptive methods in the 2 years after delivery.

Methods

In this cohort study, we interviewed 403 postpartum women in a hospital in Austin, Texas who wanted to delay childbearing for at least 2 years. Follow-up interviews were completed at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months after delivery; retention at 24 months was 83%. At each interview, participants reported their pregnancy status and contraceptive method. At the 3- and 6-month interviews participants were also asked about their preferred contraceptive method 3 months in the future. We identified types of barriers among women unable to access their preferred method, and used Cox models to analyze the risk of pregnancy from 6 to 24 months after delivery.

Results

Among women interviewed 6 months postpartum (n=377), two thirds experienced a barrier to accessing their preferred method of contraception. By 24 months postpartum, 89 women had reported a pregnancy; 71 were unintended. Between 6 months postpartum and 24 months after delivery, 77 of 377 became pregnant (20.4%) with 56 (14.9%) lost to follow-up. Women who encountered a barrier obtaining their preferred method were more likely to become pregnant <24 months after delivery. They had a cumulative risk of pregnancy of 34% (95% CI: 0.25, 0.43) as compared to 12% (95% CI: 0.05, 0.18) for women with no barrier. All but three of the women reporting an unintended pregnancy had earlier expressed interest in using LARC or a permanent method.

Conclusion

In this study, most unintended pregnancies <24 months after delivery could have been prevented or postponed had women been able to access their desired long-acting and permanent methods.

Introduction

The postpartum period has long been recognized as a critical time for women to initiate contraception; their motivation to avoid pregnancy is high and they have access to health care at delivery and often in the initial months postpartum. Although most public and private insurance policies now cover contraception, specific obstacles to immediate postpartum access to highly effective methods remain (1–6). These barriers include insurance rules that prohibit inclusion of the fee for an IUD or implant placed immediately after delivery in the global delivery reimbursement, the 30-day waiting period between consent and procedure for Medicaid sterilization, and limited or no postpartum contraceptive coverage for women whose prenatal care or deliveries are paid by some forms of Medicaid. Given the risks associated with rapid repeat pregnancies, many have called for the removal of these barriers (7–11).

However, the argument for removing barriers and increasing access would be strengthened if more was known about the demand for long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) and female and male sterilization at the time of delivery and afterwards. Although information about actual use of sterilization and LARC after delivery is available (12, 13), little is known about women’s preferences for highly effective methods and when they would like to access them (14). Additionally, retrospective information from national- and state-level data sets can be used to measure the incidence of unintended pregnancies in the 2 years after delivery (13), but it is hard to know how many of these pregnancies might have been postponed or averted had the demand for highly effective contraception been met.

In this study of postpartum women’s contraceptive preferences and use in the postpartum period in Texas, we addressed these questions by collecting information on the contraceptive methods that women wanted to be using, the level of demand for long-acting or permanent methods, and the barriers women encountered in accessing their preferred method. These data enable us to estimate the proportion of pregnancies occurring within 2 years of delivery that could have been averted through improved access to highly effective contraception in this setting.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a 24-month cohort study with 403 postpartum women in one hospital in Austin, Texas. Women were approached on the postpartum unit; interested women were administered a screening questionnaire to determine if they met the eligibility requirements: between the ages 18 and 44 years, spoke English or Spanish, had delivered a healthy singleton infant that would go home with her at discharge, lived within 50 miles of the hospital, and wanted to wait at least 2 years before having another child or have completed childbearing. The cohort included 75% patients whose deliveries were paid with Medicaid and 25% that were paid with private insurance. The proportion of Medicaid births at the hospital was 55%, nearly identical to the statewide proportion. We oversampled women with Medicaid-paid deliveries because previous research indicates these women may have difficulty accessing contraception after delivery (15). In Texas, Pregnancy Medicaid provides coverage for contraception out to 6 weeks postpartum but Emergency Medicaid does not. The sample size was determined so as to detect a difference in the risk of pregnancy of 0.2 per year between two equal sized groups, a power of 0.9 and an alpha of 0.05.

Between April and July 2012, we conducted in-person baseline interviews in the hospital immediately after delivery and contacted women by phone at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months after delivery. Women received $30 for participating in the in-person baseline interview and $15 for each of the follow-up interviews. To increase follow-up at the 18-month and 24-month follow-up interviews, all participants were notified that those who completed the last two interviews would be entered into a drawing for one of three $100 gift cards. Follow-up rates were 94% at 3 months, 95% at 6 months, 93% at 9 months, 91% at 12 months, 86% at 18 months, and 83% at 24 months. Only 56 participants were lost to follow-up between 6 and 24 months. The institutional review board at the University of Texas at Austin approved this study.

We assessed women’s contraceptive preferences with two types of questions. In the baseline and 3-month interviews we asked about the method of contraception the participant would like to be using at 6 months after delivery. At the 6-month interview, we also elicited latent demand for LARC and permanent methods with additional questions based on our previous findings that a large percentage of women using oral contraception would have preferred to use one of these more effective methods(16). Non-sterilized women who wanted no more children were asked whether they wished they had been sterilized before leaving the hospital after delivery, and if they would like their husbands to get a vasectomy. Women who had not previously expressed a preference for LARC were asked whether they would be interested in using an IUD or implant if it were offered for free or low cost (see (14) for a complete description of the measurement of contraceptive preferences). We also asked women at 6 months about the method she would like to be using at 9 months postpartum, and probed for any method the respondent might have omitted because she believed it was not covered by her insurance, or was not available from her provider.

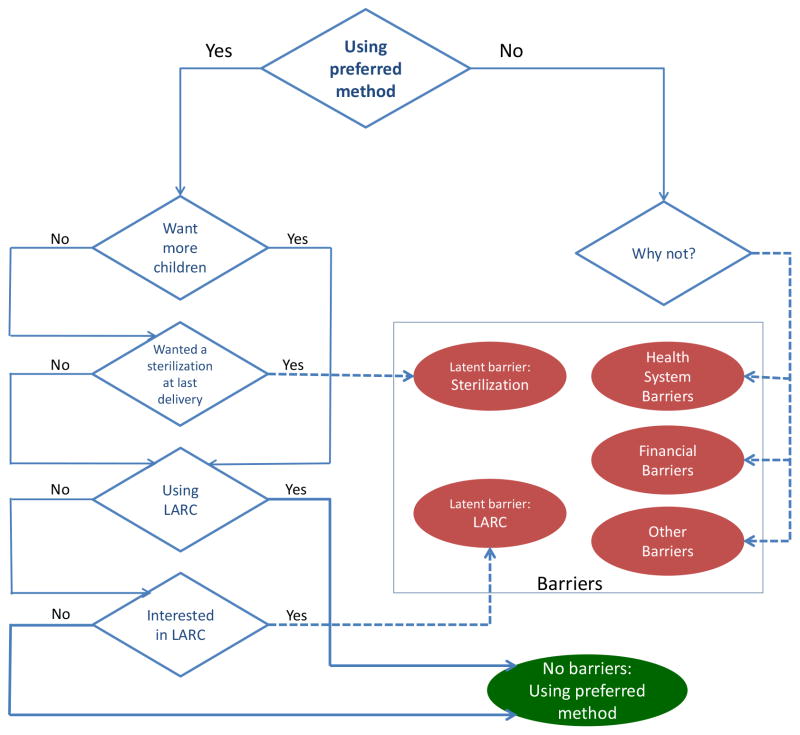

Based on women’s self-reports of method use at the 6-month interview, we determined whether women or their partners were using the method of contraception they had said that they wanted to be using at this time in the baseline and three-months postpartum interviews. If a woman was not using her preferred method, we asked open-ended questions about why she was not using this method. We then categorized these responses according to the type of barriers that had prevented women from using their preferred method: insurance coverage or other financial obstacles; health care systems barriers, such as the clinic not having the method in stock or the hospital not having a signed Medicaid consent form for sterilization; and a category of obstacles that included being told she was contraindicated for the method, having been advised against using it for another reason, and partner opposition. Women who were using the method they had said they would like to be using at 6 months postpartum, but who also stated they would like to have been sterilized at the time of their last delivery or who would like their partner to get a vasectomy, were classified as having a latent barrier for sterilization. Similarly, women who were not using an IUD or implant but who said they would consider using one of these methods were it available for free or at a nominal cost (and did not indicate they wanted a permanent method) were classified as having a latent barrier for LARC. Figure 1 details how women’s responses were used to create these categories. We excluded four women who reported a pregnancy at the 6-month interview, and were not asked these questions.

Figure 1.

Identification of barriers encountered accessing contraceptive preferences. Dashed lines highlight paths to different barrier categories. LARC, long-acting reversible contraception.

At each of the follow-up interviews, women were asked whether they had become pregnant and their current pregnancy status. If women were not still pregnant, they were asked about the outcome of the pregnancy. We also asked what contraceptive method they were using at the time of conception, and if none, why they were not using a method. Pregnancies were classified as intended if, at the time of conception, no contraception was being used because the woman was trying to become pregnant.

In this analysis, we assessed the frequency with which women encountered a barrier accessing their preferred method of contraception by the 6-month interview. We chose to focus on 6 months after delivery since at this point women have finished postpartum care, many have finished breastfeeding, and the mix of contraceptive methods used is stable (13, 14). We also examined the frequency of barriers by social and demographic characteristics, and the types of contraception being used at 6 months postpartum by women experiencing different types of barriers. We classified methods into four categories according to typical-use effectiveness (17): “less effective methods” are condoms, withdrawal, spermicides, sponges, fertility-based awareness methods, and abstinence; “hormonal methods” includes combined and progestin-only contraceptive pills, injectables, the vaginal ring, and patch; long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) are the implant, Copper-T IUD, and the levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system, while “permanent methods” are female sterilization and vasectomy.

We then estimated two Cox regression models predicting the risk of conception between the 6-month and the final interview (two years after delivery of the index birth). In the first model, the predictor was the type of method used at 6 months, while in the second the predictor was the type of barrier encountered. Cumulative risks of pregnancy by 9, 12, 18, and 24 months were estimated for each method/barrier group, and confidence intervals for those risks were estimated using survci (18). Since the aim was to assess pregnancy rates in the respective groups, we did not adjust for other socio-demographic covariates.

Finally, we classified unintended pregnancies according to the type of contraception used at the time of conception, and then examined whether women who were not using a highly effective method had expressed demand for a permanent method, and whether they had an interest in using LARC.

Results

The sample for this analysis included 377 participants who completed the 6-month interview and did not report being pregnant at that time. The cohort is largely Hispanic, with 37% born in Mexico (Table 1). More than half reported not wanting additional children at the baseline interview. Overall, 67% of women encountered a barrier accessing their preferred method, and women who experienced barriers were more likely to be younger, single, have two children, want no more children and be born in the US than women who did not report a barrier.

Table 1.

Distribution of Women at Six Months Interview, by Demographic Characteristics and Experience of a Barrier Accessing Preferred Method of Contraception*

| Demographic characteristics | All n (%) | No Barrier* n (%) | Barrier* n (%) | χ2 p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 377 (100) | 126(33) | 251 (67) | |

| Age at baseline | ||||

| 18–24 | 119 (32) | 26(22) | 93 (78) | 0.000 |

| 25–29 | 108 (29) | 31(29) | 77 (71) | |

| 30–34 | 92 (24) | 38(41) | 54 (59) | |

| 35+ | 58 (15) | 31(53) | 27 (47) | |

| Parity at baseline | ||||

| One | 112 (30) | 36(32) | 76 (68) | 0.006 |

| Two | 112 (30) | 26(23) | 86 (77) | |

| Three or more | 153 (40) | 64(42) | 89 (58) | |

| Relationship status at baseline | ||||

| Married | 196 (49) | 74(38) | 122 (62) | 0.031 |

| Cohabiting | 115 (29) | 39(34) | 76 (66) | |

| Neither married nor cohabiting | 65 (17) | 13(20) | 52 (80) | |

| Insurance status at baseline | ||||

| Private | 96 (25) | 33(34) | 63 (66) | 0.819 |

| Public | 281 (75) | 93(33) | 188 (67) | |

| Want more children at baseline | ||||

| No | 193 (51) | 45(23) | 148 (77) | 0.000 |

| Yes (in 2 years or more) | 184 (49) | 81(44) | 103 (56) | |

| Annual Family Income ($) | ||||

| <10,000 | 85 (23) | 25(29) | 60 (71) | 0.199 |

| 10,000–19,999 | 96 (25) | 31(32) | 65 (68) | |

| 20,000–34,999 | 72 (19) | 30(42) | 42 (58) | |

| 35,000–74,999 | 54 (14) | 13(24) | 41 (76) | |

| 75,000 or more | 58 (15) | 23(40) | 35 (60) | |

| Education | ||||

| < High School | 135 (36) | 47(35) | 88 (65) | 0.922 |

| High School | 104 (28) | 34(33) | 70 (67) | |

| > High School | 137 (36) | 45(33) | 92 (67) | |

| Birthplace | ||||

| United States | 209 (55) | 57(27) | 152 (73) | 0.018 |

| Mexico | 142 (38) | 58(41) | 84 (59) | |

| Other | 26 (7) | 11(42) | 15 (58) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 237 (63) | 83(35) | 154 (65) | 0.138 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 36 (10) | 7(19) | 29 (81) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 88 (23) | 28(32) | 60 (68) | |

| Other | 16 (4) | 8(50) | 8(50) | |

Excludes 4 women who reported being pregnant at the 6-month interview

At 6 months after delivery, two thirds of women in the cohort had either expressed a latent demand for LARC or sterilization or were not using the method they had said they would like to be using at this time (Table 2). Taken together, explicit financial and health-system barriers were encountered by 29% of the cohort. Latent barriers for either LARC or a permanent method were found in 23%.

Table 2.

Current Method at 6 Months Postpartum by Type of Barrier*

| Type of Barrier | Sterilization n (%) | LARC n (%) | Hormonal n (%) | Less effective methods n (%) | No method n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No barriers | 66 (52) | 28 (22) | 16 (13) | 16 (13) | 0 (0) | 126 (100) |

| Health-system barriers | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 7 (23) | 23 (74) | 0 (0) | 31 (100) |

| Financial barriers | 1 (1) | 4 (5) | 23 (29) | 48 (62) | 2 (3) | 78 (100) |

| Latent barrier: Sterilization | 0 (0) | 14 (31) | 12 (27) | 19 (42) | 0 (0) | 45 (100) |

| Latent barrier: LARC | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 15 (35) | 27 (63) | 1 (2) | 43 (100) |

| Other barriers | 0 (0) | 6 (11) | 14 (26) | 32 (59) | 2 (4) | 54 (100) |

|

| ||||||

| Total | 67 (18) | 53 (14) | 87 (23) | 165 (44) | 5 (1) | 377 (100) |

Excludes 4 women who reported being pregnant at the 6-month interview

Among women with no barrier, three quarters relied on permanent methods or LARC. In contrast, 42–74% of women in the rest of the cohort who encountered barriers to using their preferred method were relying on less-effective methods, with 23–35% using hormonal methods.

A total of 89 women reported a pregnancy during the 24 months after delivery and 12 of these pregnancies were conceived before the 6-month follow-up interview. Of the 77 reported pregnancies conceived after the 6-month interview, 63 were reported by women who also encountered a barrier. In the first Cox regression model, significant differences in the risk of pregnancy were found according to the type of contraceptive method used at the 6-month interview (Table 3). By 24 months after delivery, the estimated cumulative risk of pregnancy was 43% for women who were using less effective methods at 6 months postpartum, and 27% for those using hormonal methods. In the second Cox model, we also found significant differences in the risk of pregnancy according to the type of barrier women encountered in accessing their preferred method of contraception prior to the 6-month interview (Table 3). Women with no barrier at 6 months after delivery had a cumulative risk of pregnancy at 24 months of 12%, whereas women who encountered a health-system or financial barrier at 6 months had estimated cumulative risks of pregnancy of 47% and 38%, respectively. The estimated risks of pregnancy for the women who had a latent demand for LARC or who had encountered financial or health systems barriers at 6 months were at least three times greater than the risk for women who did not encounter a barrier. The only exception was women who did not want more children and wished they had been sterilized at the time of their last delivery. Aggregating across all of the barrier categories, the cumulative risk of pregnancy for women with a barrier was was 34% (95% CI: 0.25, 043).

Table 3.

Cumulative Risk of Pregnancy at 24 Months After Delivery

| Predictor | Cumulative Risk of Pregnancy 24 months | [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|

| Method used at 6 months after delivery | ||

| LARC or permanent method | 0.07 | [0.02, 0.13] |

| Hormonal method | 0.27 | [0.15, 0.39] |

| Less effective method* | 0.43 | [0.31, 0.55] |

| Type of Barrier Encountered | ||

| None (using preferred method) | 0.12 | [0.05, 0.18] |

| Health system barrier | 0.47 | [0.16, 0.77] |

| Financial barrier | 0.38 | [0.22, 0.54] |

| Sterilization, elicited barrier | 0.13 | [0.02, 0.25] |

| LARC, elicited barrier | 0.44 | [0.21, 0.67] |

| Other barrier | 0.33 | [0.15, 0.51] |

| Any barrier | 0.34 | [0.25, 0.43] |

CI: Confidence Interval. Cumulative risk of pregnancy estimated from Cox proportional models.

Includes 5 women using no method

Of the 89 women who reported a pregnancy during the two-year period of follow-up, only 18 (20%) reported stopping contraceptive use to become pregnant, indicating that the pregnancy was planned. Among the remaining 71 women reporting unintended pregnancies, 46% would have preferred to use a permanent method, and 87% said they wanted to use LARC, or would be interested in using an implant or an IUD were it available for free or at minimal cost. About half of the women who were using a less effective or no method said they would like to be using a permanent method, and over 85% had expressed a preference for or interest in LARC (Table 4). Of all 71 women reporting an unintended pregnancy, only three had no interest in either LARC or sterilization. However, five women who reported pregnancies also reported using a long-acting method or having been sterilized at the time of conception.

Table 4.

Interest in LARC and desire for Sterilization among Women Reporting Unintended Pregnancies

| Method used at conception | n | Wanted sterilization n (%) | Interested in LARC n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hormonal | 15 | 6 (40) | 14 (93) |

| Less-effective methods | 43 | 22 (51) | 37 (86) |

| None | 8 | 4 (50) | 7 (88) |

Discussion

Several recent studies have demonstrated that many women experience an unintended pregnancy within two years of delivery, and the majority of these closely spaced pregnancies occur among women using less-effective contraceptive methods (5, 13, 19). The results from our 2-year prospective study support and expand upon these previous findings and suggest that many of these pregnancies may be due to barriers that postpartum women encounter accessing their preferred method of contraception.

Although the majority of women in our study wanted to use a long-acting or permanent method, two thirds stated they had been unable to access one of these methods by 6 months after delivery and were relying on less-effective forms of contraception. The reasons women gave for not using their preferred method point to the importance of assessing women’s contraceptive preferences and putting measures in place that would increase access to these methods immediately after delivery. One such measure is improving insurance coverage for postpartum contraception, as indicated both by the 21% of women reporting a financial barrier as their reason for not using their preferred method, as well as by the 11% of women who said they would be interested in using a LARC method if it were available for free or at a minimal cost. Similarly, the role that authorizing reimbursement for postpartum LARC and eliminating the 30-day waiting period for sterilization for Medicaid patients could play is evident from the 8% reporting health-system barriers as a reason for not using their preferred method as well as the additional 12% who reported wishing they had been sterilized at the time of their last delivery.

We also found that the method women were using at 6 months postpartum was closely associated with the risk of pregnancy in the following 18 months. This highlights the need to ensure that women are able to access the full range of contraceptive methods postpartum, while they are still having regular or scheduled appointments with obstetric providers. These encounters can assist women with planning how they will obtain their desired method of contraception within the confines of a health care system that may be changing rapidly due to rule changes, insurance mandates, and funding levels.

Increasing access to postpartum contraception would likely reduce the number of unintended rapid repeat pregnancies, since many women in our sample who encountered a barrier to their preferred method had a higher risk of pregnancy compared to those who were able to access their method of choice by 6 months postpartum. In fact, a novel finding from this study is that the large majority (95%) of unintended pregnancies were conceived by women who would have preferred to have been using a more-effective method of contraception at 6 months after delivery.

There are two anomalous findings. We are unsure whether the low risk of pregnancy among women who wanted to be sterilized at delivery may have resulted from the more effective use of hormonal and barrier methods by women with high motivation to avoid pregnancy, or from a greater incidence of unreported induced abortion in this group. At first glance, the finding that women who would like to have been sterilized at the time of delivery had lower rates of pregnancy than other women contradicts the results from another study conducted in Texas (20), but that study referred only to live births and was based on hospital records. Second, we were surprised that four women using a Copper-T IUD, and one woman who said she had been sterilized reported pregnancies. However, without access to their medical records, we were not able to corroborate the clinical details of these cases, including whether they experienced a failed sterilization or had a partial or complete expulsion of the IUD. Based on interviewer notes, at least one of the IUD failures appeared to be related to expulsion.

In this study, we infer contraceptive preferences indirectly for some women based on their responses to questions about interest in using an IUD or an implant, or their desire for a permanent method. An important issue is whether these probes led respondents to declare a preference for highly effective methods in order to please the interviewer. We are confident of the reliability of the probe regarding desire for sterilization at the time of the last delivery based on a prior study in El Paso. There, we re-interviewed women about 18 months after initially asking this question and found that the large majority still wanted to be sterilized and expressed coherent reasons for this desire(16). We do not yet have such confirmation for the probe regarding interest in LARC, but restricting the criteria for interest in LARC to women who had stated such a preference before the prompt would not alter the results substantially.

An important limitation of this study is that it is based on a fairly small sample of largely Latina women who may have higher preference for IUDs than other women (21, 22) and was conducted in Texas, which drastically reduced public funding for subsidized family planning services in 2011 (23, 24). Therefore, women in this sample may have a higher unmet demand for highly effective contraception. However, the use of LARC and permanent methods among postpartum women is highly variable across states(12), indicating that women in other settings may also experience barriers to accessing these methods. A second limitation is that pregnancies ending in abortion were likely under-reported in the telephone follow-up interviews, as they are in most surveys (25).

In spite of these limitations, this analysis highlights the role that removing the barriers to immediate postpartum insertion of IUDs and implants, and increasing access to postpartum female sterilization could have in reducing unintended pregnancies in the 2 years after delivery. By asking about contraceptive preferences, our study also suggests a new way of identifying pregnancies that could have been averted if women had access to all methods of contraception. Births averted by publicly subsidized family planning programs are typically estimated by comparing current contraceptive use with what women would be using in the absence of a subsidy (26–29). However, this approach usually involves strong assumptions, and does not assess the impact of any potential expansion or improvement in care. The prospective analysis used in this study provides a basis for making such estimates. Finally, there is a need to examine contraceptive preferences among different groups of women in other contexts to identify the range and variation of barriers and their effects.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Susan T. Buffett Foundation and the Society of Family Planning (SFPRF7-4). Infrastructural support was provided by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R24 042849) to the Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin, and (R24HD047879) to the Office of Population Research, Princeton University. Kari White also received support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K01 HD079563).

The authors thank Chloe Dillaway and Natasha Mevs-Korff for superb research assistance.

Footnotes

Presented at the North American Forum on Family Planning, Miami, Florida, October 10–14, 2014, and at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, San Diego, California, April 30–May 2, 2015.

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Teal SB. Postpartum Contraception: Optimizing Interpregnancy Intervals. Contraception. 2014;89(6):487–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zapata LB, Murtaza S, Whiteman MK, Jamieson DJ, Robbins CL, Marchbanks PA, et al. Contraceptive counseling and postpartum contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):171e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.07.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whiteman MK, Cox S, Tepper NK, Curtis KM, Jamieson DJ, Penman-Aguilar A, et al. Postpartum intrauterine device insertion and postpartum tubal sterilization in the United States. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012 Feb;206(2):127 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiel de Bocanegra H, Chang R, Howell M, Darney P. Interpregnancy intervals: impact of postpartum contraceptive effectiveness and coverage. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2014 Apr;210(4):311 e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiel de Bocanegra H, Chang R, Menz M, Howell M, Darney P. Postpartum contraception in publicly-funded programs and interpregnancy intervals. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):296–303. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182991db6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogburn JA, Espey E, Stonehocker J. Barriers to intrauterine device insertion in postpartum women. Contraception. 2005 Dec;72(6):426–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aiken AR, Creinin M, Kaunitz AM, Nelson AL, Trussell J. Global fee prohibits postpartum provision of the most effective reversible methods. Contraception. 2014;90(5):466–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borrero S, Zite N, Potter JE, Trussell J. Medicaid policy on sterilization--anachronistic or still relevant? New England Journal of Medicine. 2014 Jan 9;370(2):102–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1313325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006 Apr 19;295(15):1809–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.15.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez MI, Evans M, Espey E. Advocating for immediate postpartum LARC: increasing access, improving outcomes, and decreasing cost. Contraception. 2014 Nov;90(5):468–71. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tocce KM, Sheeder JL, Teal SB. Rapid repeat pregnancy in adolescents: do immediate postpartum contraceptive implants make a difference? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012 Jun;206(6):481 e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.White K, Potter JE, Hopkins K, Grossman D. Variation in postpartum contraceptive method use: Results from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Contraception. 2014;89(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White K, Teal SB, Potter JE. Contraception After Delivery and Short Interpregnancy Intervals Among Women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(6):1471–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potter JE, Hopkins K, Aiken AR, Hubert C, Stevenson A, White K, et al. Unmet demand for highly effective postpartum contraception in Texas. Contraception. 2014;90(5):488–95. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weston MRS, Martins SL, Neustadt AB, Gilliam ML. Factors influencing uptake of intrauterine devices among postpartum adolescents: a qualitative study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012 Jan;206(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.06.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potter JE, White K, Hopkins K, McKinnon S, Shedlin MG, Amastae J, et al. Frustrated Demand for Sterilization Among Low-Income Latinas in El Paso, Texas. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2012;44(4):228–35. doi: 10.1363/4422812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trussell J, Guthrie KA. Choosing a contraceptive: efficacy, safety, and personal considerations. In: Hatcher RA, et al., editors. Contraceptive Technology. 20th revised. New York: Ardent Media; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cefalu M. Pointwise confidence intervals for the covariate-adjusted survivor function in the Cox model. Stata J. 2011;11(1):64–81. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gemmill A, Lindberg LD. Short interpregnancy intervals in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(1):64–71. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182955e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thurman AR, Janecek T. One-year follow-up of women with unfulfilled postpartum sterlization requests. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1071–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f73eaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werth SR, Secura GM, Broughton HO, Jones ME, Dickey V, Peipert JF. Contraceptive continuation in Hispanic women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):312 e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh RH, Rogers RG, Leeman L, Borders N, Highfill J, Espey E. Postpartum contraceptive choices among ethnically diverse women in New Mexico. Contraception. 2014 Jun;89(6):512–5. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White K, Grossman D, Hopkins K, Potter JE. Cutting family planning in Texas. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(13):1179–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1207920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White K, Hopkins K, Aiken ARA, Stevenson A, Hubert Lopez C, Grossman D, et al. The impact of reproductive health legislation on family planning clinic services in Texas. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):851–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Shifts in intended and unintended pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. Am J Public Health. 2014 Feb;104(Suppl 1):S43–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foster DG, Rostovtseva DP, Brindis CD, Biggs MA, Hulett D, Darney PD. Cost savings from the provision of specific methods of contraception in a publicly funded program. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):446–51. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster DG, Klaisle CM, Blum M, Bradsberry ME, Brindis CD, Stewart FH. Expanded state-funded family planning services: estimating pregnancies averted by the Family PACT Program in California, 1997–1998. Am J Public Health. 2004 Aug;94(8):1341–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frost JJ, Sonfield A, Zolna MR, Finer LB. Return on investment: a fuller assessment of the benefits and cost savings of the US publicly funded family planning program. Milbank Q. 2014 Dec;92(4):696–749. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trussell J. The cost of unintended pregnancy in the United States. Contraception. 2007 Mar;75(3):168–70. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]