Abstract

Public acceptance of evolution in Northeastern U.S. is the highest nationwide, only 59%. Here, we compare perspectives about evolution, creationism, intelligent design (ID), and religiosity between highly educated New England faculty (n=244; 90% Ph.D. holders in 40 disciplines at 35 colleges/universities) and college students from public secular (n=161), private secular (n=298), and religious (n=185) institutions: 94/3% of the faculty vs. 64/14% of the students admitted to accepting evolution openly and/or privately, and 82/18% of the faculty vs. 58/42% of the students thought that evolution is definitely true or probably true, respectively. Only 3% of the faculty vs. 23% of the students thought that evolution and creationism are in harmony. Although 92% of faculty and students thought that evolution relies on common ancestry, one in every four faculty and one in every three students did not know that humans are apes; 15% of the faculty vs. 34% of the students believed, incorrectly, that the origin of the human mind cannot be explained by evolution, and 30% of the faculty vs. 72% of the students was Lamarckian (believed in inheritance of acquired traits). Notably, 91% of the faculty was very concerned (64%) or somehow concerned (27%) about the controversy evolution vs creationism vs ID and its implications for science education: 96% of the faculty vs. 72% of the students supported the exclusive teaching of evolution while 4% of the faculty vs. 28% of the students favored equal time to evolution, creationism and ID; 92% of the faculty vs. 52% of the students perceived ID as not scientific and proposed to counter evolution or as doctrine consistent with creationism. Although ≈30% of both faculty and students considered religion to be very important in their lives, and ≈20% admitted to praying daily, the faculty was less religious (Religiosity Index faculty=0.5 and students=0.75) and, as expected, more knowledgeable about science (Science Index faculty=2.27 and students=1.60) and evolution (Evolution Index faculty=2.48 and students=1.65) than the students. Because attitudes toward evolution correlate (1) positively with understanding of science/evolution and (2) negatively with religiosity/political ideology, we conclude that science education combined with vigorous public debate should suffice to increase acceptance of naturalistic rationalism and decrease the negative impact of creationism and ID on society’s evolution literacy.

Keywords: Assessment, College education, Controversy science versus popular belief

Introduction

Forty percent of Americans accept the concept of evolution (Miller et al. 2006; The Gallup Poll 2009). In the intellectually progressive Northeastern U.S., favorable views toward evolution only reach 59%, the highest score nationwide (The Pew Research Center for the People & the Press 2005). Creationism and intelligent design split the public’s support to evolution in the U.S. and nourish the controversy between scientific knowledge and popular belief (Padian 2009; Padian and Matzke 2009; Forrest 2010; Matzke 2010). The U.S. ranks 33rd in a list of 34 other countries where acceptance of evolution has been polled, in contrast to Iceland, Denmark, Sweden, France, Japan, and the UK, top in the list where ≈75–85% of adults accept evolution (Miller et al. 2006).

The concept of evolution provides naturalistic explanations about the origin of life, its diversification and biogeography, and the synergistic phenomena resulting from the interaction between life and the environment (Paz-y-Miño C. and Espinosa 2009a, b); mutations, gene flow, genetic drift, and natural selection shape life’s biological processes in Earth’s ecosystems (Mayr 2001). Since the publication of The Origin of Species by Charles Darwin, in 1859, Darwinian evolution has been scrutinized experimentally; today the theory of evolution is widely accepted by the scientific community (Coyne 2009; Dawkins 2009). In contrast, creationism, theistic evolution, creation science, or young-earth creationism (Petto and Godfrey 2007; Matzke 2010; Phy-Olsen 2010) rely on supernatural causation to explain the origin of the universe and life. These views are not recognized by scientists as evidence-based explanations of cosmic processes (Padian 2009; Scott 2009; Paz-y-Miño C. and Espinosa 2009a, b).

The doctrine of intelligent design (ID), born in the 1980s proposes that a Designer is responsible, ultimately, for the assemblage of complexity in biological systems; according to ID, evolution cannot explain holistically the origin of the natural world, nor the emergence of intricate molecular pathways essential to life, nor the huge phylogenetic differentiation of life, and instead ID proposes an intelligent agent as the ultimate cause of nature (Forrest and Gross 2007a, b; Young and Edis 2004; Miller 2007, 2008; Phy-Olsen 2010). In 2005, ID was exposed in court (Dover, Pennsylvania, Kitzmiller et al. versus Dover School District et al. 2005; Padian and Matzke 2009; Wexler 2010) for violating the rules of science by “invoking and permitting supernatural causation” in matters of evolution, and for “failing to gain acceptance in the scientific community.” Today, “design creationism” (as we also refer to it due to its designer/creator-based foundations) although defeated by science and in the courts, grows influential in the U.S., Europe, Australia, and South America (Cornish-Bowden and Cárdenas 2007; Padian 2009; Forrest 2010; Matzke 2010; Wexler 2010).

Acceptance of evolution among the general public, high schools students and teachers, college students, and scientists has been documented (Bishop and Anderson 1990; Downie and Barron 2000; Moore and Kraemer 2005; Miller et al. 2006; Donnelly and Boone 2007; Moore 2007; Berkman et al. 2008; Hokayem and BouJaoude 2008; Coalition of Scientific Societies 2008; The Gallup Poll 2008, 2009; Paz-y-Miño C. and Espinosa 2009a, b), little is known, however, about tendencies of acceptance of evolution by highly educated audiences, like university professors. A cultural assumption is that such audiences are consistently supportive of science and remain distant from belief-based perspectives about the natural world (but see Ecklund and Scheitle 2007; Gross and Simmons 2009). Here, we examine the views of New England faculty (n = 244) from 35 colleges and universities, who were polled in three areas: (1) the controversy over evolution versus creationism versus ID, (2) their understanding of how the evolutionary process works, and (3) their personal convictions concerning the evolution and/or creation of humans in the context of their own religiosity. We compared and contrasted the faculty’s perspectives with those of students from three representative New England institutions: public secular (n=161), private secular (n= 298), and religious (n=185). Assessing faculty’s versus students’ perception of evolution in one of the historically most progressive regions of the U.S. is crucial for determining the magnitude of the impact of creationism and ID on attitudes toward science, reason, and education in science. The New England states have among the highest evolution education standards in the U.S. (letter grade for coverage of evolution in state science standards: Connecticut D, Maine C, Massachusetts B, New Hampshire A, Rhode Island B, Vermont B; Mead and Mates 2009); however, only two out of three New Englanders accept evolution (above). By understanding opinions about evolution among “highly educated” versus “in-the-process-of-acquiring-education” audiences, we aim at improving the approach with which evolution and science are communicated to the public, contributing to curricular/pedagogical reform for their effective teaching in college, and minimizing the negative effects of creationism and ID on the U.S. educational system (Paz-y-Miño C. and Espinosa 2009a, b).

Methods

We sampled 35 academic institutions (17 colleges and 18 universities) widely distributed geographically in all New England states (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont; Table 1). In each state, we selected two public secular, two private secular, and two religious colleges and/or universities, except for Maine where only one religious institution was identified (Table 1). We contacted via email (addresses obtained from institutional websites) 992 faculty according to two criteria: first, members of the biology departments, or close equivalents (e.g., ecology and evolutionary biology, molecular and cell biology, and natural sciences), of each institution (regardless of sex), who are usually highly educated in evolution; and second, a similar number of nonbiology faculty, across some 40 different disciplines, who were selected randomly (sex ratio 1:1; Table 1). To compare New England faculty views with those of college students, we surveyed students from three representative New England institutions (email requests to all enrolled students): public secular University of Massachusetts Dartmouth (UMassD Pub, 7,982 students contacted), private secular Roger Williams University (RWU Priv, 3,806 students contacted), and religious Providence College (PC Rel, 3,910 students contacted) (Table 2). Both faculty and student profiles of those who responded to the survey were comparable in respect to residency and workplace location (New England states), but differed, as we expected, in respect to place of birth (faculty usually belong to diverse cultural backgrounds: New England 42.6%, East Coast 17.6%, other states 27.5%, foreign countries 12.3%; students mean Pub+Priv+Rel: New England 78%, East Coast 14%, other states 5%, foreign countries 3%; Table 2) and level of education (faculty: Ph.D. holders 90.2%, doctoral degree or equivalent 2.9%, masters degree 6.9%; students mean Pub+Priv+Rel: freshman 19.4%, sophomore 17.4%, junior 16.7%, senior 19.0%; Table 2).

Table 1.

New England institutions sampled in the study

| State/Institution (type)a | Faculty contacted | Faculty responders | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.b | Biologists | Nonbiologistsc | No. | % per subtotal state)d |

% of total responderse |

F (%)e | M (%)e | |||

| F (%) | M (%) | F (%) | M (%) | |||||||

| Connecticut (CT) | ||||||||||

| University of Connecticut (Pub) | 67 | 11 | 22 | 17 | 17 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| University of Hartford (Pub) | 14 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Yale University (Priv) | 18 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Quinnipiac University (Priv) | 30 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Fairfield University (Rel Catholic) | 24 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Albertus Magnus College (Rel Catholic) | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Subtotal CT | 159 | 34 (21.4)d | 45 (28.3)d | 39 (24.5)d | 41 (25.8)d | 38 | 23.9d | 15.6e | NA | NA |

| Maine (ME) | ||||||||||

| University of Southern Maine (Pub) | 34 | 5 | 12 | 8 | 9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| University of Maine Orono (Pub) | 60 | 14 | 16 | 15 | 15 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| University of New England (Priv) | 24 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Husson University (Priv) | 16 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| St. Joseph’s College of Maine (Rel Catholic) | 8 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Subtotal ME | 142 | 30 (21.1)d | 41 (28.9)d | 35 (24.6)d | 36 (25.4)d | 38 | 26.8d | 15.6e | NA | NA |

| Massachusetts (MA) | ||||||||||

| University of Massachusetts Boston (Pub) | 50 | 5 | 20 | 12 | 13 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Fitchburg State College (Pub) | 26 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Springfield College (Priv) | 18 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Wheaton College (Priv) | 18 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Merrimack College (Rel Catholic) | 14 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Stonehill College (Rel Catholic | 18 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Subtotal MA | 144 | 26 (18.1)d | 46 (31.9)d | 36 (25.0)d | 36 (25.0)d | 34 | 23.6d | 14.0e | NA | NA |

| New Hampshire (NH) | ||||||||||

| University of New Hampshire Durham (Pub) | 78 | 11 | 28 | 19 | 20 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Plymouth State University (Pub) | 28 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Dartmouth College (Priv) | 59 | 7 | 22 | 15 | 15 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Colby-Sawyer College (Priv) | 20 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Rivier College (Rel Catholic) | 8 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| St. Anselm College (Rel Catholic) | 22 | 1 | 10 | 6 | 5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Subtotal NH | 215 | 35 (16.3)d | 72 (33.5)d | 54 (25.1)d | 54 (25.1)d | 50 | 23.3d | 20.4e | NA | NA |

| Rhode Island (RI) | ||||||||||

| University of Rhode Island (Pub) | 32 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Rhode Island College (Pub) | 32 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Brown University (Priv) | 46 | 7 | 16 | 12 | 11 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Roger Williams University (Priv) | 30 | 4 | 11 | 8 | 7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Salve Regina University (Rel Catholic) | 10 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Providence College (Rel Catholic) | 28 | 3 | 11 | 6 | 8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Subtotal RI | 178 | 32 (18.0)d | 57 (32.0)d | 45 (25.3)d | 44 (24.7)d | 41 | 23.0d | 16.8e | NA | NA |

| Vermont (VT) | ||||||||||

| University of Vermont-Burlington (Pub) | 50 | 10 | 15 | 12 | 13 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Castleton State College (Pub) | 20 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Middlebury College (Priv) | 28 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Norwich University (Priv) | 26 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Saint Michael’s College (Rel Catholic) | 20 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Green Mountain College (Rel Methodist) | 10 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Subtotal VT | 154 | 36 (23.4)d | 41 (26.6)d | 38 (24.7)d | 39 (25.3)d | 43 | 27.9d | 17.6e | NA | NA |

| Grand total | 992 | 193 (19.5)f | 302 (30.4)f | 247 (24.9)f | 250 (25.2)f | 244 (24.6)f | 90 (36.9)e | 154 (63.1)e | ||

Type of institution refers to public secular (Pub), private secular (Priv) and religious (Rel)

Faculty were contacted according to two criteria: first, members of the biology departments, or equivalent, of each institution (regardless of sex), who are usually highly educated in evolution; and second, a similar number of nonbiology faculty, across all disciplines, who were selected randomly (sex ratio, 1:1)

Nonbiologists correspond to random selection of faculty from ca. 40 different disciplines, as follows: CT University of Connecticut (n = 9): Anthropology, Communication Sciences, English, History, Human Development and Family Studies, Linguistics, Philosophy, Political Science, Psychology; University of Hartford (n = 6): Art History, Communications, Computer Science, Legal Studies, Politics and Government, Sociology; Yale University (n = 3): Astronomy, Forestry and Environmental Studies, History; Quinnipiac University (n = 4): Business, Computer Science and Interactive Digital Design, Journalism, Public Relations; Fairfield University (n = 4): Education, Philosophy, Political Science, Religious Studies; Albertus Magnus College (n = 2): Mathematics, Psychology. ME University of Southern Maine (n = 6): Chemistry, Environmental Science, Engineering, History, Mathematics and Statistics, Philosophy; University of Maine-Orono (n = 7): Anthropology, Art, Engineering, International Affairs, Mathematics and Statistics, Nursing, Political Science; University of New England (n = 5): Business and Communications, English and Language Studies, Global Humanities, Psychology, Women’s and Gender Studies; Husson University (n = 3): Business, Education, Legal Studies; Saint Joseph’s College of Maine (n = 4): Elementary Education, Criminal Justice, Exercise Science, Theology. MA University of Massachusetts Boston (n = 7): Applied Linguistics, English, History, Mathematics, Political Science, Nursing and Health Sciences, Sociology; Fitchburg State College (n = 4): Economics, History, Industrial Technology, Mathematics; Springfield College (n = 4): Education, Mathematics/Physics and Computer Science, Social Work, Visual and Performing Arts; Wheaton College (n = 3): Economics, English, Music; Merrimack College (n = 3): Electrical Engineering, Sociology, Religious and Theological Studies; Stonehill College (n = 4): Business Administration, Economics, Mathematics, Religious Studies. NH University of New Hampshire-Durham (n = 7): Anthropology, Art and Art History, Education, English, Health Management and Policy, History, Mathematics and Statistics; Plymouth State University (n = 6): Business, Criminal Justice, Economics, Education, Mathematics, Philosophy; Dartmouth College (n = 9): Anthropology, Computer Science, Economics, Engineering Science, English, Geography, Mathematics, Physics and Astronomy, Women’s and Gender Studies; Colby-Sawyer College (n = 4): Business Administration, Education, Psychology, Social Science; Rivier College (n = 3): Business Administration, Nursing, Psychology; St. Anselm College (n = 3): English, History, Humanities. RI University of Rhode Island (n = 4): Chemistry, English, Nursing, Journalism; Rhode Island College (n = 6): Art, Communications, English, History, Philosophy, Physical Sciences; Brown University (n = 8): Anthropology, Education, History, Philosophy, Political Sciences, Psychology, Sociology, Visual Arts; Roger Williams University (n = 11): Architecture, Chemistry, Communications, Computer Sciences, Creative Writing, Dance, English, History, Political Sciences, Psychology, Theater; Salve Regina University (n = 3): Anthropology, Business Studies, Religious and Theological Studies; Providence College (n = 8): Art History, English, History, Philosophy, Political Science, Psychology, Secondary Education, Sociology. VT University of Vermont-Burlington (n = 9): Anthropology, Biochemistry, Education, Engineering, English, Geology, Mathematics and Statistics, Molecular Physiology and Biophysics, Physics; Castleton State College (n = 4): Business Administration, Sociology/Social Work and Criminal Justice, Music, Natural Sciences; Middlebury College (n = 4): Economics, Education Studies, Geography, Religion; Norwich University (n = 6): Chemistry and Biochemistry, Geology and Environmental Science, Mathematics, Nursing, Physics, Sports Medicine; Saint Michael’s College (n = 5): Computer Science, Economics, History, Political Science, Sociology and Anthropology; Green Mountain College (n = 3): Environmental Studies, Communications and Journalism, History

Percentage estimated in respect to subtotal number of faculty contacted per state

Percentage estimated in respect to total number of faculty responding to the survey (N = 244)

Percentage estimated in respect to grand total number of faculty contacted to participate in the survey (N = 992)

Table 2.

Profile of faculty and students from public secular, private secular, and religious institutions who participated in the study

| Faculty | Students | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public secular | Private secular | Religious | Grand total | |||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | %a | |

| Total | 244 | 27.5a | 161 | 18.1a | 298 | 33.6a | 185 | 20.8a | 888 | 100a |

| Females | 90 | 36.9b | 96 | 59.6b | 185 | 62.1b | 111 | 60.0b | 482 | 54.3a |

| Males | 154 | 63.1b | 65 | 40.4b | 113 | 37.9b | 74 | 40.0b | 406 | 45.7a |

| PhD degree | 220 | 90.2b | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 220 | 24.8a |

| Doctorate degree | 7 | 2.9b | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 0.8a |

| Masters degree | 17 | 6.9b | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 17 | 1.9a |

| Freshman | NA | NA | 49 | 30.4b | 79 | 26.5b | 44 | 23.8b | 172 | 19.4a |

| Sophomore | NA | NA | 46 | 28.6b | 67 | 22.5b | 42 | 22.7b | 155 | 17.4a |

| Junior | NA | NA | 28 | 17.4b | 70 | 23.5b | 50 | 27.0b | 148 | 16.7a |

| Senior | NA | NA | 38 | 23.6b | 82 | 27.5b | 49 | 26.5b | 169 | 19.0a |

| New England | 104 | 42.6b, c | 146 | 90.7b, g | 223 | 74.8b, k | 124 | 67.0b, o | 597 | 67.2a |

| East Coast | 43 | 17.6b, d | 6 | 3.7b, h | 57 | 19.1b, l | 38 | 20.5b, p | 144 | 16.2a |

| Other states | 67 | 27.5b, e | 4 | 2.5b, i | 10 | 3.4b, m | 16 | 8.7b, q | 97 | 10.9a |

| Foreign countries | 30 | 12.3b, f | 5 | 3.1b, j | 8 | 2.7b, n | 7 | 3.8b, r | 50 | 5.7a |

Percentages in respect to grand total number of participants or “responders” to the survey (n = 888), which is a fraction of the number of faculty (n = 992) plus students (public = 7,982; private = 3,806; and religious = 3,910) contacted via email and asked to take part in the study

Percentages in respect to total number of participants per group of faculty or college students from public secular, private secular or religious institutions

New England faculty natives correspond to MA, 13.7%; CT, 6.8%; VT, 6.8%; ME, 5.9%; NH, 4.9%; and RI, 4.5%

East Coast faculty natives correspond to NY, 9.6%; PA, 4.4%; NJ, 2.4%; and MD and VA, ≈1.2%

Other states faculty natives correspond to CA, 7.3%; MI, 3.6%; CO and TX, 2.5%; IL, 2.0%; OH, 1.6%; and 17 other states plus Puerto Rico, 10.5%

Foreign countries faculty correspond to 15 nationalities (Europe and UK, 7.6%; Canada, 2.4%; and Australia, China, Libya, and Brazil, 2.3%)

New England students at public secular institution were natives from MA, 86.9%; RI, 2.8%; and CT, <1%

East Coast students at public secular institution were natives from NY, 2.7%; NJ and VA, <1%

Other states students at public secular institution were natives from four states AZ, FL, MI, and TX, 2.5%

Foreign countries students at public secular institution correspond to four nationalities (Cape Verde, Cameroon, Philippines, and Brazil, 3.1%)

New England students at private secular institution were natives from MA, 29.1%; CT, 19.4%; RI, 15.5%; NH, 6.6%; VT, 2.8; ME, 1.4%

East Coast students at private secular institution were natives from NY, 9.7%; NJ, 5.1%; PA, 2.2%; MD, 1.1%; VA, <1%

Other states students at private secular institution were natives from nine states CA, CO, GA, IL, IN, KT, MI, TN, and WA, 3.4%

Foreign countries students at private secular institution correspond to eight nationalities (France, Ghana, India, Korea, Lebanon, Peru, Romania, and UK, 2.7%)

New England students at religious institution were natives from MA, 37.2%; CT, 11.2%; RI, 14.1%; NH, 2.0%; ME, 1.5%; VT, <1%

East Coast students at religious institution were natives from NY, 10.2%; NJ, 6.8%; PA, 2.5%; DE and VA, 1.0%

Other states students at religious institution were natives from 11 states CA, FL, IL, IN, MN, MO, OH, OR, SC, TN, and TX, 8.7%

Foreign countries students at religious institution correspond to seven nationalities (Bosnia, Canada, Ghana, Korea, Latvia, Portugal, and Zimbabwe, 3.8%)

Eight hundred and eighty-eight faculty (n=244, 27.5%) and students (n=644, 72.5%) responded to an 11-question anonymous and voluntary online survey to assess their views about evolution, creationism, and intelligent design (questions 1–7, below), as well as about their understanding of how the evolutionary process works (Questions 8–9, below), and their personal convictions concerning both the evolution and/or creation of humans and degree of religiosity (Questions 10–11, below). All participants were free to withdraw from the survey at any time; no risks or discomfort were involved in the study. The Institutional Review Board of UMassD approved the New England faculty (surveyed during the first week of April and third week of May 2010) and UMassD students’ study (second week of September 2009), and the Human Subjects/Institutional Review Boards of RWU (third week of October 2009) and PC (third week of April 2009) approved the surveying of their own students. All participants answered questions 1–11 (but see exceptions below) in order and were instructed to not skip or go back to previous questions to fix and/or compare answers. Questions 1–7 and 10 had five (A, B, C, D, or E) or three (A, B, or C) choices per question, respectively; Questions 8–9 and 11 were true/false and had five (A, B, C, D, or E) or three (A, B, or C) subcomponents (each true/false), respectively. All choices per question, including the true/false options, were presented randomly and only one choice was possible per question, except for question 11 that allowed responders to select as many as three choices. For the purpose of reporting the data in this article and matching the description of each question with the figure legends (results, below), here we state the questions as follows:

Questions Addressing Views About Evolution, Creationism, and ID

-

Question 1

Evolution, creationism, and intelligent design in the science class. Which of the following explanations about the origin and development of life on Earth should be taught in science classes? A=evolution, B=equal time to evolution, creationism, intelligent design, C=creationism, D=intelligent design, and E=do not know enough to say.

-

Question 2

ID. Which of the following statements is consistent with ID? A=ID is not scientific but has been proposed to counter evolution based on false claims, B=ID is religious doctrine consistent with creationism, C=no opinion, D=ID is a scientific alternative to evolution and of equal scientific validity among scientists, and E=ID is a scientific theory about the origin and evolution of life on Earth.

-

Question 3

Evolution and your reaction to it. Which of the following statements fits best your position concerning evolution? A=hearing about evolution makes me appreciate the factual explanation about the origin of life on Earth and its place in the universe, B=hearing about evolution makes no difference to me because evolution and creationism are in harmony, C=hearing about evolution makes me uncomfortable because it is in conflict with my faith, D=hearing about evolution makes me realize how wrong scientists are concerning explanations about the origin of life on Earth and the universe, and E=do not know enough to say.

-

Question 4

Your position about the teaching of human evolution. With which of the following statements do you agree? A=I prefer science courses where evolution is discussed comprehensively and humans are part of it, B=I prefer science courses where plant and animal evolution is discussed but not human evolution, C=I prefer science courses where the topic evolution is never addressed, D=I avoid science courses with evolutionary content, and E=do not know enough to say.

-

Question 5

Evolution in science exams. Which of the following statements fits best your position concerning science exams? A=faculty: instructors should have no problem giving exams with questions concerning evolution, or students: I have no problem answering questions concerning evolution, B=science exams should always include some questions concerning evolution, C=faculty: students should prefer to not answer questions concerning evolution, or students: I prefer to not answer questions concerning evolution, D=faculty: students should never answer questions concerning evolution, or students: I never answer questions concerning evolution, and E=do not know enough to say.

-

Question 6

Your willingness to discuss evolution. Select the statement that describes you best: A=I accept evolution and express it openly regardless of other’s opinions, B=no opinion, C=I accept evolution but do not discuss it openly to avoid conflicts with friends and family, D=I believe in creationism and express it openly regardless of others’ opinions, and E=I believe in creationism but do not discuss it openly to avoid conflicts with friends and family.

-

Question 7

Your overall opinion about evolution (question adapted from Miller et al. 2006). Select the statement with which you agree most about “evolution is”: A=definitely true, B=probably true, C=definitely false, D=probably false, and E=do not know enough to say.

Questions Addressing Views About the Evolutionary Process

-

Question 8

An acceptable definition of evolution. Indicate if each of the following definitions of evolution is either true or false: A=gradual process by which the universe changes, it includes the origin of life, its diversification and the synergistic phenomena resulting from the interaction between life and the environment, B=directional process by which unicellular organisms, like bacteria, turn into multicellular organisms, like sponges, which later turn into fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals, and ultimately humans, the pinnacle of evolution, C=gradual process by which monkeys, such as chimpanzees, turn into humans, D=random process by which life originates, changes, and ends accidentally in complex organisms such as humans, and E=gradual process by which organisms acquire traits during their lifetimes, such as longer necks, larger brains, resistance to parasites, and then pass on these traits to their descendants.

-

Question 9

Evidence about the evolutionary process. Indicate if each of the following statements about evolution is either true or false: A=all current living organisms are descendants of common ancestors, which have evolved for thousands, millions, or billions of years, B=humans are apes, relatives of chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans, C=the hominid (human lineage) fossil record is so poor that scientists cannot tell with confidence that modern humans evolved from ancestral forms, D=the origin of the human mind and consciousness cannot be explained by evolution, and E=the universe, our solar system, and planet Earth are finely tuned to embrace human life.

Questions Addressing Views About Evolution and/or Creation Of Humans and Responders’ Religiosity

-

Question 10

Human evolution with or without creation (question adapted from Berkman et al. 2008). Indicate if each of the following statements about evolution with or without God’s intervention is either true or false: A=humans have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years but God had no part in this process, B=humans have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years but God guided this process, and C=God created humans in their present form within the last 10,000 years.

-

Question 11

Your religiosity. Indicate if each of the following statements about religiosity is either true or false, select all that apply (question adapted from Pew Global Attitudes Project 2007): A=faith in God is necessary for morality, B=religion is very important in my life, and C=I pray at least once a day.

Religiosity, Understanding-of-Science, and Evolution Indexes

The Pew Global Attitudes Project (2007) has used the three choices of Question 11 (above) to generate a Religiosity Index (RI), a powerful predictor of religious views worldwide (47 countries), which we applied to our New England faculty and students samples. RI ranges from 0 to 3 (least to most religious position): +1 if responders believe that faith in God is necessary for morality, +1 if religion is very important in their lives, and +1 if they pray daily.

To account for the levels of understanding of science and the evolutionary process, we generated two descriptive indexes (Science Index (SI), Evolution Index (EI)), analogous to RI (above). Thus, we could compare degree of religiosity (RI) with levels of understanding of science (SI) and evolution (EI). Note that scholars in the field of attitudes toward evolution (Bishop and Anderson 1990; Downie and Barron 2000; Trani 2004; Paz-y-Miño C. and Espinosa 2009a, b) have postulated that these three factors might determine an individual’s acceptance of evolution. Our SI and EI range from zero to three (lower to higher levels of understanding of science and evolution) and rely on three questions each, which were selected from a pool of five questions about science and ten about evolution (all part of the online surveys); the suitable questions for each index showed variability between the responses by faculty versus students and were, therefore, informative to discriminate between both groups: SI +1 if responders rejected the idea that scientific theories are based on opinions by scientists, +1 if they disagreed with the notion that scientific arguments are as valid and respectable as their nonscientific counterparts, and +1 if they rejected the statement that crime-scene and accident-scene investigators use a different type of scientific method to investigate a crime or an accident; EI +1 if responders rejected the idea that organisms acquire beneficial traits during their lifetimes and then pass on these traits to their descendants, +1 if they disagreed with the notion that during evolution monkeys such as chimpanzees can turn into humans, and +1 if they rejected the statement that the origin of the human mind and consciousness cannot be explained by evolution.

Statistical Analyses

For the five choice questions (1–7), we compared New England faculty (Fac) versus college students from three types of academic institutions (Pub, Priv, or Rel) and analyzed separately the data generated in each of the questions (i.e., Questions 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, or 7; choices A, B, C, D, or E). Data from each question were organized in 4×5 contingency tables, for example, Fac, Pub, Priv, Rel×A, B, C, D, or E (Chi-square tests, null hypotheses rejected at P≤0.05). Because Questions 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, or 7 had none or very few responders (<5%; note that Chi-square analyses are inaccurate when over 20% of the expected values are less than five; Sieger and Castellan 1988) in one, two, or three of the choices (E or DE or CDE), we eliminated such choices and created 4×2, 4×2, 4×2, 4×2, 4×3, and 4×2 contingency tables for the remaining groups in each question, respectively (Chi-square tests, null hypotheses rejected at P≤0.05). In Question 10, we analyzed the choices (A, B, or C) as function of the students’ institutional affiliation (Pub, Priv, and Rel). Because choice C had very few responders, we eliminated it (rationale above) and created a 2×3 contingency table A, B×Pub, Priv, or Rel (Chi-square tests, null hypotheses rejected at P≤0.05). For the true/false questions (Questions 8–9 and 11), we organized the data corresponding to each subcomponent of the question (Questions 8–9: subcomponents A, B, C, D, and E; Question 11: subcomponents A, B, and C) in separate 2×4 or 2×3 contingency tables per each of the five or three subcomponents per question, respectively. For example, Questions 8, subcomponent A: True, False×Fac, Pub, Priv, or Rel, Question 9, subcomponent A: True, False×Fac, Pub, or Priv, and Question 11, subcomponent A: True, False × Fac, Pub, or Priv, (Chi-square tests, null hypotheses rejected at P≤0.05). Note that for Questions 9 and 11 we could not sample students from the religious institution, thus we only compared faculty versus students from the public and private institutions; for Question 10, we sampled only the students (Pub, Priv, or Rel) and compared their perspectives to data from the literature, particularly surveys of high school teachers (Berkman et al. 2008), and extrapolated such comparisons to our analysis (see “Discussion”) of patterns of acceptance of evolution by faculty. Pair-wise comparisons between relevant groups in all questions were analyzed with sign test two-tail, null hypotheses rejected at P≤0.05. Although we instructed participants to not skip questions, they could do it freely (Human Subjects/Institutional Review Boards’ policies, above); therefore, the total number of faculty or student responders per question varied, as reported in the figure captions (below): Fac mean=230, r=216–244; students Pub mean=124, r=113–161, Priv mean=260, r=180–298, and Rel mean=174, r=165–185. The RI, SI, and EI (above) are descriptive values which range from zero to three each; we generated them as such and discussed them in the context of factors that might determine an individual’s acceptance of evolution.

Results

Survey Response Rates

Faculty

Two hundred and forty-four (24.6%) of the 992 faculty contacted to participate in the study (biologists, 495: F=19.5%, M=30.4%, nonbiologists in ca. 40 disciplines 497: F=24.9%, M=25.2%) completed the survey (Table 1), a response rate comparable to analogous email/online studies (24%, The Pew Research Center for the People & the Press 2009). The average number of faculty contacted per state was 165 (r=142–215) and the average percent of responders per state was 25 (r=23.0–27.9). Of all responders (n=244), 36.9% were females and 63.1% were males (Table 1).

Students

Response rate by students varied among institutions: Pub, 161 (2.0% of 7,982 contacted); Priv, 298 (7.8% of 3,806 contacted); and Rel, 185 (4.7% of 3,910 contacted) (Table 2); these values were consistent with previous online sampling of these institutions where the demographic profile of participants in the surveys resembled closely the institutional profiles (Paz-y-Miño C. and Espinosa 2009a, b). Of all responders (n=644), ≈60% were females and ≈40% were males (means Pub+Priv+Rel; Table 2).

Views About Evolution, Creationism, and ID

Evolution, Creationism and Intelligent Design in the Science Class

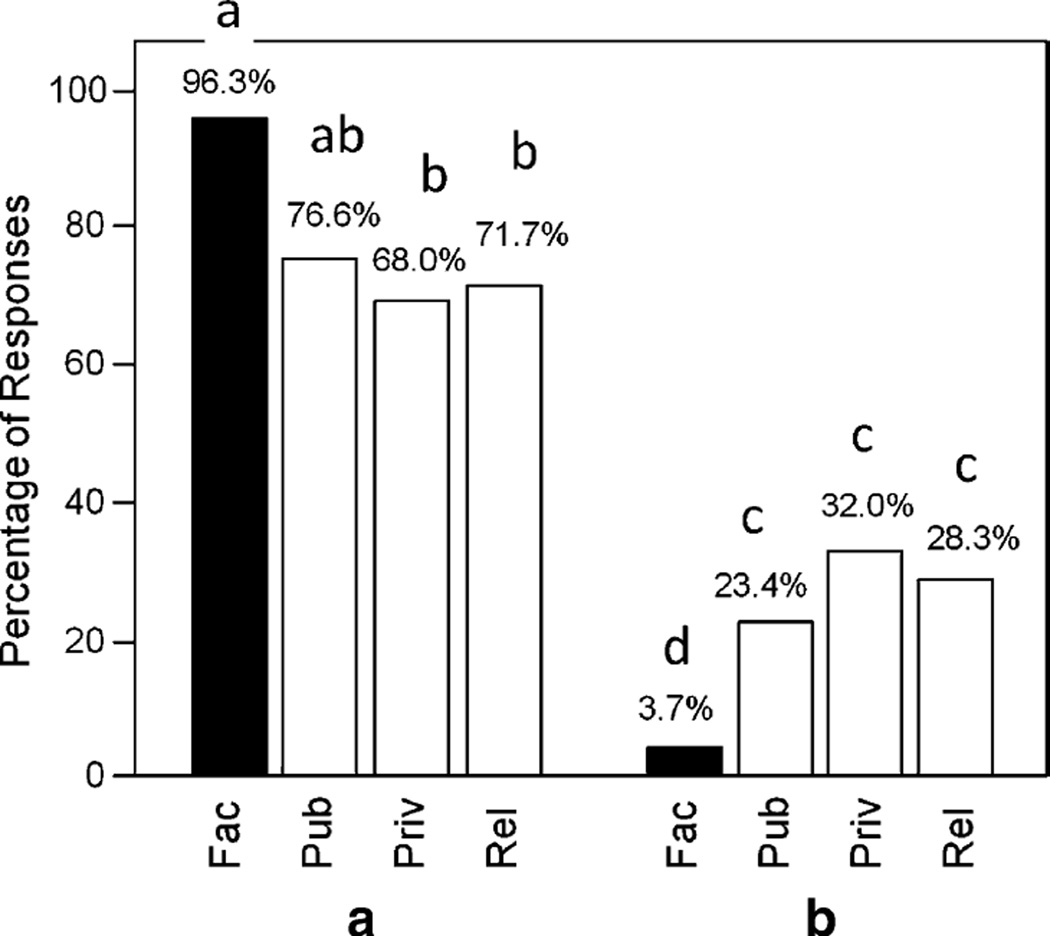

Faculty and students differed in their views about the teaching of evolution (Fig. 1; Chi-square=27.072; df=3; P≤0.001): 96.3% of the faculty versus 72% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) considered that evolution should be taught in science classes as an explanation about the origin and development of life on Earth; in contrast, 3.7% of the faculty versus 28% of the students (mean Pub+ Priv+Rel) favored equal time to evolution, creationism and intelligent design. Support for the exclusive teaching of evolution by faculty versus students from the private (68.0%) and religious (71.7%) institutions was significantly different (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparison, P≤0.05), however, the level of support to evolution by the students from the public secular institution (76.6%) was statistically similar to that of the faculty (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparison, P=0.17). Although faculty’s support for the “equal time” option was negligible (3.7%), at least one in five (Pub) to one in three students (Priv and Rel) favored it (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of New England faculty (Fac, black bars) versus college students (white bars) from public secular (Pub), private secular (Priv), and religious (Rel) institutions who consider one of the following explanations about the origin and development of life on Earth should be taught in science classes: A evolution and B equal time to evolution, creationism, and intelligent design. Comparisons among groups: Chi-square=27.072; df=3; P≤0.001; lowercase letters indicate sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05. Fac, n=241; Pub, n=120; Priv, n=266; and Rel, n=173

Intelligent Design

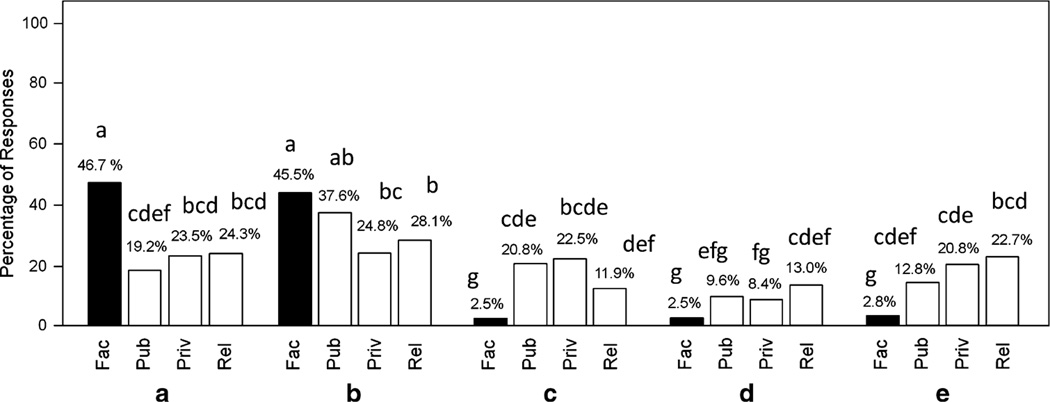

Faculty had clearly defined opinions about ID, but the students’ perception of ID varied (Fig. 2; Chi-square=63.899; df=12; P≤0.001): 46.7/45.5% of the faculty versus 22/30% of the students (means Pub+Priv+ Rel) perceived ID as either not scientific and proposed to counter evolution based on false claims or as religious doctrine consistent with creationism, respectively. Only the students from the public institution (Pub=37.6%) were statistically similar to the faculty in considering ID a religious doctrine (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparison, P=0.43). A negligible percent of faculty in comparison to a significant percent of students (means Pub+Priv+Rel) had either no opinion about ID (2.5% faculty versus 18% students), considered ID a scientific alternative to evolution and of equal scientific validity among scientists (2.5% faculty versus ten percent students), or thought of ID as a scientific theory about the origin of life on Earth (2.8% faculty versus 19% students, sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Percentage of New England faculty (Fac, black bars) versus college students (white bars) from public secular (Pub), private secular (Priv), and religious (Rel) institutions who consider one of the following statements to be consistent with intelligent design (ID): A ID is not scientific but has been proposed to counter evolution based on false claims; B ID is religious doctrine consistent with creationism; C no opinion; D ID is a scientific alternative to evolution and of equal scientific validity among scientists; E ID is a scientific theory about the origin and evolution of life on Earth. Comparisons among groups: Chi-square=63.899; df=12; P≤0.001; lowercase letters indicate sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05. Fac, n=244; Pub, n=125 l; Priv, n=298; and Rel, n=185

Evolution and Responders’ Reaction to it

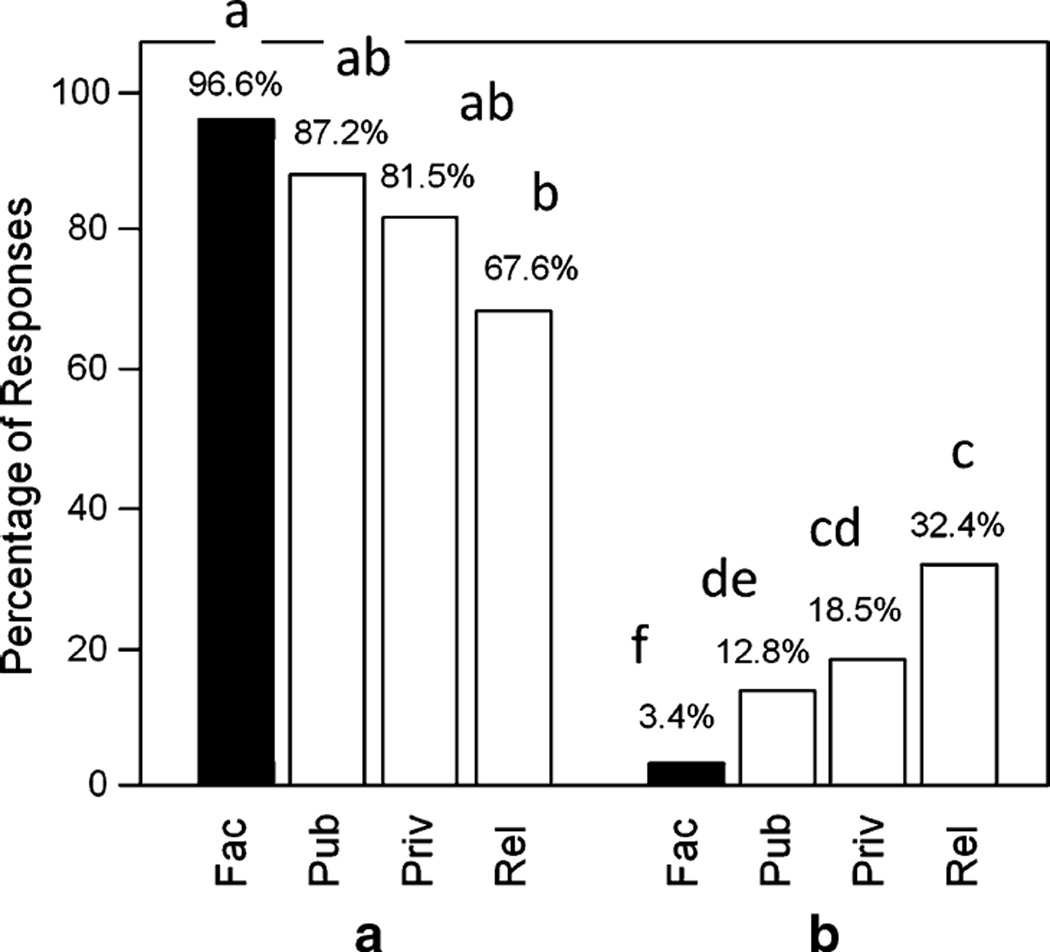

Faculty and students differed in their position about evolution (Fig. 3; Chi-square=31.615; df=3; P≤0.001): 96.6% of the faculty versus 79% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) thought that hearing about evolution makes them appreciate the factual explanation about the origin of life on Earth and its place in the universe; in contrast, 3.4% of the faculty versus 23% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) considered that hearing about evolution makes no difference because evolution and creationism are in harmony. Both the students from the public (Pub=87.2%) and private (Priv=81.5%) institutions were statistically similar to the faculty in preferring solely evolutionary explanations in science classes about the origin of life (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≥0.05; Fig. 3). Note that the students from the public, private and religious institutions are about four, six and ten times more likely than the faculty to think that evolution and creationism are in harmony, respectively (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Percentage of New England faculty (Fac, black bars) versus college students (white bars) from public secular (Pub), private secular (Priv), and religious (Rel) institutions who think one of the following statements fits best their position concerning evolution: A hearing about evolution makes me appreciate the factual explanation about the origin of life on Earth and its place in the universe; B hearing about evolution makes no difference to me because evolution and creationism are in harmony. Comparisons among groups: Chi-square=31.615, df=3, P≤0.001; lowercase letters indicate sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05. Fac, n=236; Pub, n=117; Priv, n=259; and Rel, n=176

Position About the Teaching of Human Evolution

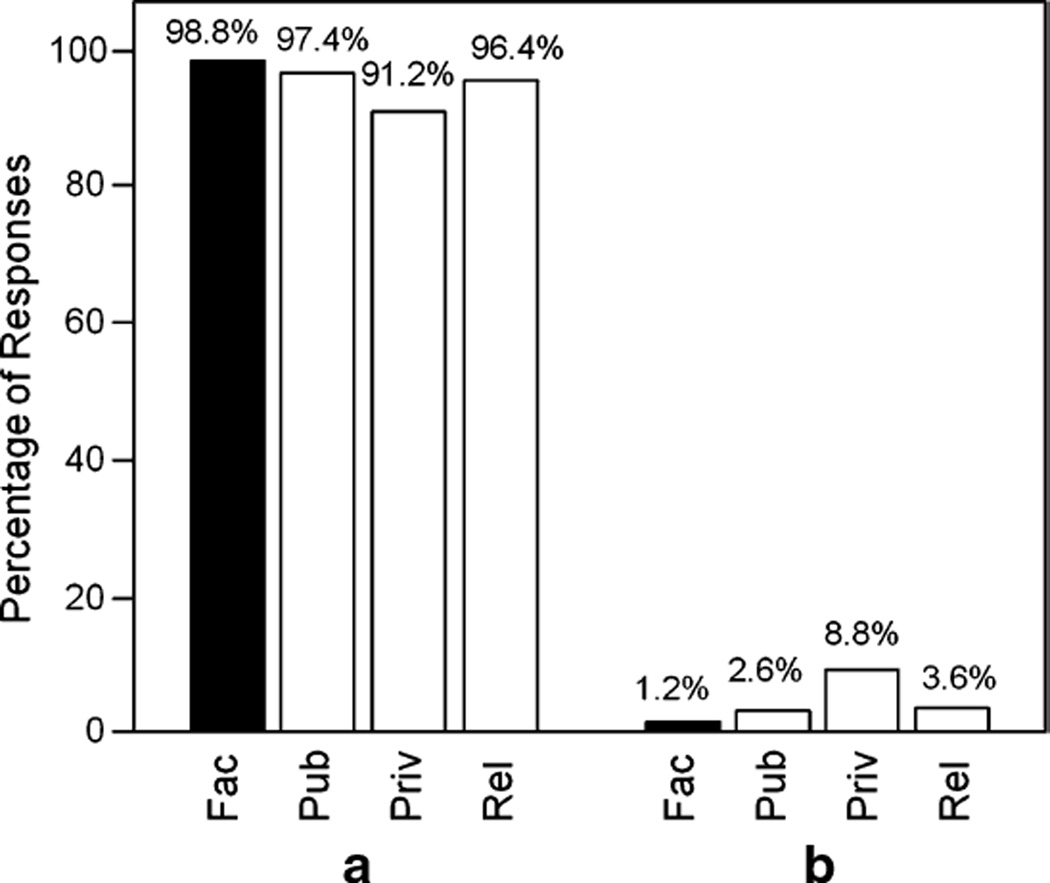

Faculty and students agreed on their views about the teaching of human evolution (Fig. 4; Chi-square=6.802; df=3; P= 0.078): 98.8% of the faculty versus 95% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) preferred science courses where evolution is discussed comprehensively and humans are part of it, and only 1.2% of the faculty versus five percent of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) preferred evolution discussions about plants and animals but not humans. In each case (i.e., science courses including or excluding human evolution) faculty versus student responses were statistically similar (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≥0.05; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Percentage of New England faculty (Fac, black bars) versus college students (white bars) from public secular (Pub), private secular (Priv), and religious (Rel) institutions who agree with one of the following statements concerning their own education: A I prefer science courses where evolution is discussed comprehensively and humans are part of it; B I prefer science courses where plant and animal evolution is discussed but not human evolution. Comparisons among groups: Chi-square=6.802; df=3; P=0.078. Fac, n=242; Pub, n=117; Priv, n=261; and Rel, n=169

Evolution in Science Exams

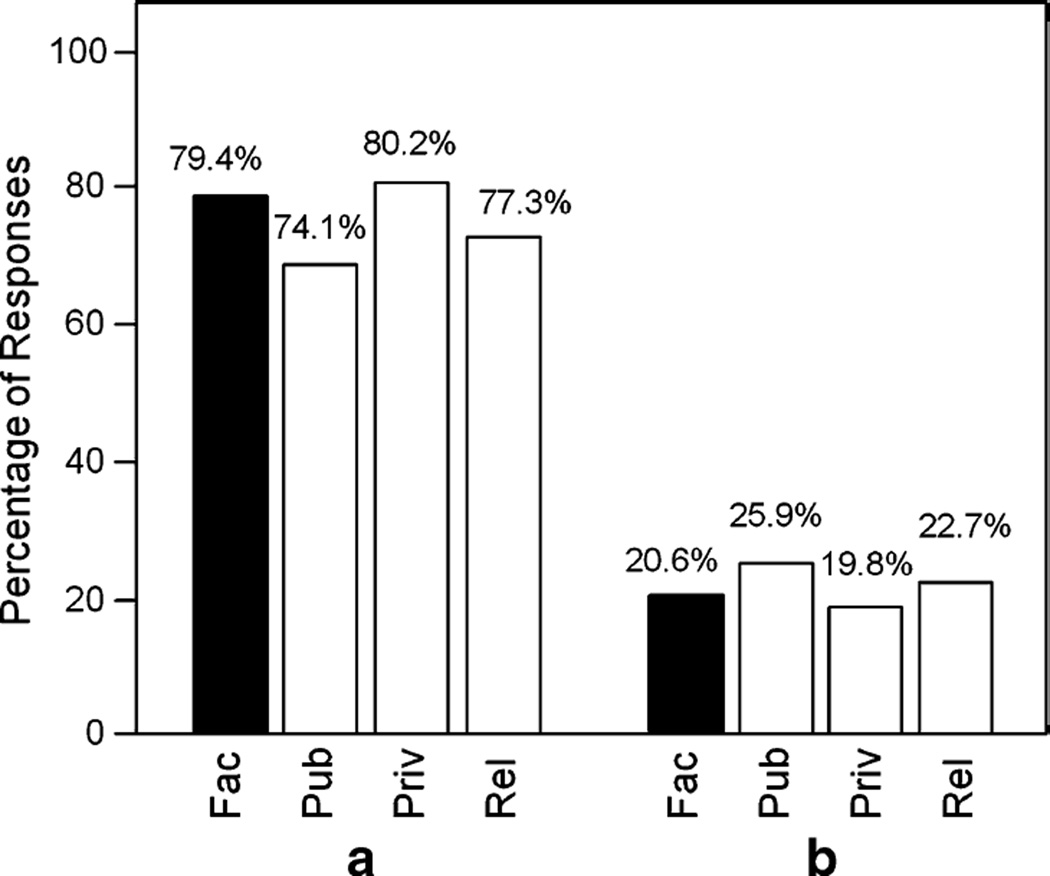

Faculty and students shared opinions about the inclusion of evolution in science exams (Fig. 5; Chi-square=1.204; df=3; P=0.752): about 78% of the combined faculty plus student responders (mean Fac+Pub+Priv+Rel) had no problem with either instructors including questions concerning evolution in exams or answering questions concerning evolution in exams, respectively, and 22% (mean Fac+Pub+Priv+Rel) considered that exams should always include some questions concerning evolution. In each case (i.e., optional or required inclusion of questions about evolution in exams) faculty versus student responses were statistically similar (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≥0.05; Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Percentage of New England faculty (Fac, black bars) versus college students (white bars) from public secular (Pub), private secular (Priv), and religious (Rel) institutions who agree with one of the following statements concerning evolution in science exams: A Fac: instructors should have no problem giving exams with questions concerning evolution, or students: I have no problem answering questions concerning evolution; B science exams should always include some questions concerning evolution. Comparisons among groups: Chi-square=1.204; df=3; P=0.752. Fac, n=238; Pub, n=116; Priv, n=258; and Rel, n=172

Willingness to Discuss Evolution

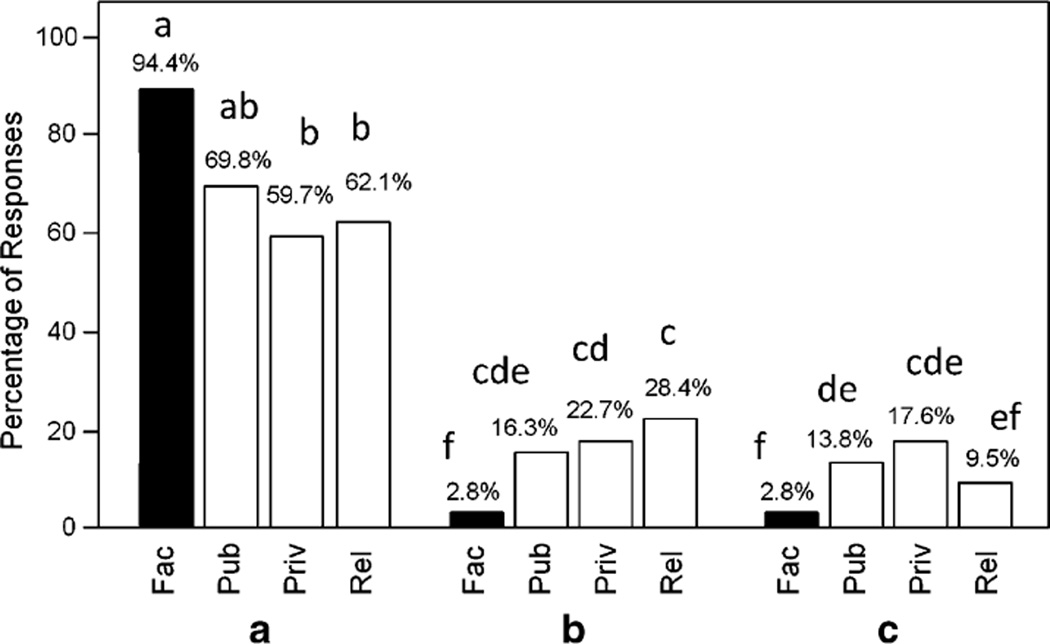

Faculty and students differed in their willingness to offer opinions about evolution (Fig. 6; Chi-square=41.326; df=6; P≤0.001): 94.4% of the faculty versus 64% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) indicated they accept evolution and express it openly regardless of others’ opinions, 2.8% of the faculty versus 22% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) preferred not to comment on this issue, and 2.8% of the faculty versus 14% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) admitted they accept evolution but do not discuss it openly to avoid conflicts with friends and family. Only the students from the public institution (Pub=69.8%) were statistically similar to the faculty in accepting evolution openly (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparison P=0.072).

Fig. 6.

Percentage of New England faculty (Fac, black bars) versus college students (white bars) from public secular (Pub), private secular (Priv), and religious (Rel) institutions who believe one of the following statements describes them best: A I accept evolution and express it openly regardless of others’ opinions; B no opinion; and C I accept evolution but do not discuss it openly to avoid conflicts with friends and family. Comparisons among groups: Chi-square=41.326; df=6; P≤0.001; lowercase letters indicate sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05. Fac, n=216; Pub, n=116; Priv, n=273; and Rel, n=169

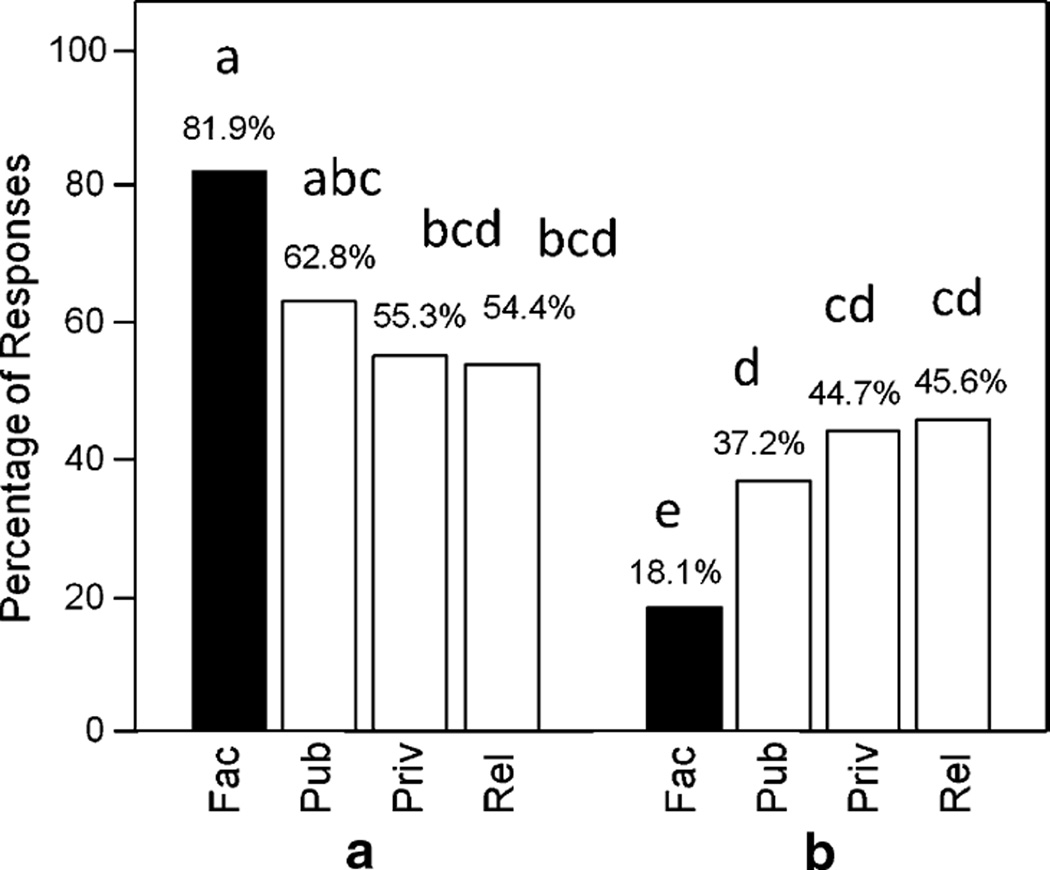

Overall Opinion About Evolution

Faculty and students differed in their overall opinion about evolution (Fig. 7; Chi-square=21.788; df=3; P≤0.001): 81.9% of the faculty versus 58% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) thought that evolution is definitely true, and 18.1% of the faculty versus 42% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) thought that evolution is probably true. Only the students from the public institution (Pub=62.8%) were statistically similar to the faculty in thinking that evolution is definitely true (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparison, P=0.134).

Fig. 7.

Percentage of New England faculty (Fac, black bars) versus college students (white bars) from public secular (Pub), private secular (Priv), and religious (Rel) institutions who think evolution is: A definitely true and B probably true. Comparisons among groups: Chi-square=21.788; df=3; P≤0.001; lowercase letters indicate sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05. Fac, n=216; Pub, n=113; Priv, n=253; and Rel, n=171

Views About the Evolutionary Process

An Acceptable Definition of Evolution

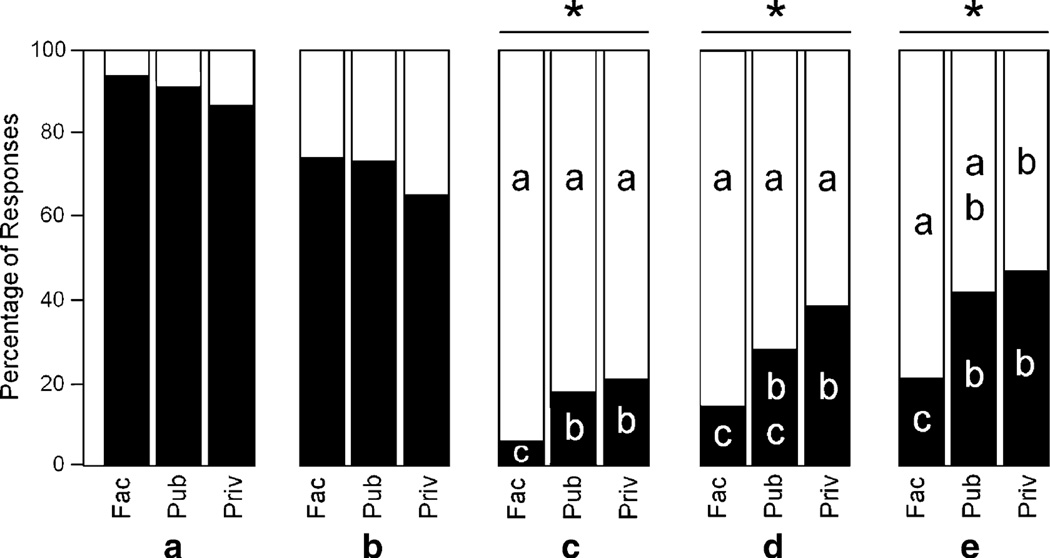

There was noticeable variation in the views of faculty versus students about alternative definitions of evolution (Fig. 8): 80% of the faculty and 84% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) considered definition A of evolution as true: gradual process by which the universe changes, it includes the origin of life, its diversification and the synergistic phenomena resulting from the interaction between life and the environment; faculty and student responses were statistically similar (within group comparisons, Chi-square=3.827; df=3; P= 0.281); note that definition A was the most comprehensive included in the survey. Eleven percent of the faculty versus 50% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) considered definition B of evolution as true: directional process by which unicellular organisms, like bacteria, turn into multicellular organisms, like sponges, which later turn into fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals and ultimately humans, the pinnacle of evolution (within group comparisons, Chi-square=48.511; df=3; P≤0.001); the faculty correctly rejected this definition (89% considered it false, sign test two-tail pair-wise comparison P≤0.05; Fig. 8), while the students’ true/false responses (Pub, Priv, and Rel) were similar to each other and to chance (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≥0.05; Fig. 8); note that definition B implies purpose in evolution and goal toward “humanity.” Six percent of the faculty versus 26% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) considered definition C of evolution as true: gradual process by which monkeys, such as chimpanzees, turn into humans (within group comparisons, Chi-square= 23.455; df=3; P≤0.001); the faculty correctly rejected this definition (94% considered it false, sign test two-tail pairwise comparison P≤0.05; Fig. 8) while the students’ true/false responses (Pub, Priv, and Rel) were similar to each other and to chance (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≥0.05; Fig. 8); note that definition C asserts that chimpanzees are “monkeys” and that humans evolved from them. Thirty percent of the faculty and 29% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) considered definition D of evolution as true: random process by which life originates, changes, and ends accidentally in complex organisms such as humans; both faculty and students correctly rejected this definition (70% and 71%, respectively) and their responses were statistically similar (within group comparisons, Chi-square= 0.291; df=3; P=0.962); note that definition D implies that evolution is random and accidental. Thirty-one percent of the faculty versus 72% of the students (mean Pub +Priv+Rel) considered definition E of evolution as true: gradual process by which organisms acquire traits during their lifetimes, such as longer necks, larger brains, resistance to parasites, and then pass on these traits to their descendants (within group comparisons, Chi-square= 50.003; df=3; P≤0.001); 69% of the faculty versus 28% of the students (mean Pub+Priv+Rel) correctly rejected this Lamarckian definition, note that faculty and students true/false responses were both contrasting (Fac 31/69% versus students 72/28% means Pub+Priv+Rel) and statistically different (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05; Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Percentage of New England faculty (Fac) versus college students from public secular (Pub), private secular (Priv), and religious (Rel) institutions who consider the following definitions of evolution to be either true (black bars) or false (white bars): A gradual process by which the universe changes, it includes the origin of life, its diversification and the synergistic phenomena resulting from the interaction between life and the environment; B directional process by which unicellular organisms, like bacteria, turn into multicellular organisms, like sponges, which later turn into fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals, and ultimately humans, the pinnacle of evolution; C gradual process by which monkeys such as chimpanzees, turn into humans; D random process by which life originates, changes, and ends accidentally in complex organisms such as humans; and E gradual process by which organisms acquire traits during their lifetimes, such as longer necks, larger brains, resistance to parasites, and then pass on these traits to their descendants. Comparisons within groups (asterisks indicate significance): A, Chi-square=3.827; df=3; P=0.281. B, Chi-square=48.511; df=3; P≤0.001. C, Chi-square=23.455; df=3; P≤0.001. D, Chi-square=0.291; df=3; P=0.962; E, Chi-square=50.003; df=3; P≤0.001. Lowercase letters indicate sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons within groups, P≤0.05. Fac, n=221; Pub, n=161; Priv, n=223; Rel, n=185

Evidence About the Evolutionary Process

Faculty and students varied in their understanding of how evolution works (Fig. 9); because we could not assess this topic among students from the religious institution (rationale above), here we compare faculty only with students from the public and private institutions: 94% of the faculty and 89% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) correctly considered statement A as true: all current living organisms are descendants of common ancestors, which have evolved for thousands, millions, or billions of years; faculty and student responses were statistically similar (within group comparisons, Chi-square=4.097; df=2; P=0.129). Seventy-four percent of the faculty versus 70% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) correctly considered statement B as true: humans are apes, relatives of chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans; faculty and student responses were statistically similar (within group comparisons, Chi-square= 2.623; df=2; P=0.269). Four percent of the faculty versus 20% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) considered statement C as true: the hominid (human lineage) fossil record is so poor that scientists cannot tell with confidence that modern humans evolved from ancestral forms (within group comparison Chi-square=13.411; df=2; P=0.001); significantly less faculty than students thought that this statement was true (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05; Fig. 9); note that both 96% of the faculty and 80% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) correctly rejected this statement, and these responses were statistically similar (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≥0.05; Fig. 9). Fifteen percent of the faculty versus 34% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) considered statement D as true: the origin of the human mind and consciousness cannot be explained by evolution (within group comparison Chi-square=14.533; df=2; P≤0.001); faculty responses were statistically similar to those by the students from the public institution (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≥0.05; Fig. 9) but differed from those by the students from the private institution (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05; Fig. 9); note that both 85% of the faculty and 66% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) correctly rejected this statement and that these responses were statistically similar (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≥0.05; Fig. 9). Twenty-one percent of the faculty versus 44% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) considered statement E as true: the universe, our solar system and planet Earth are finely tuned to embrace human life (within group comparisons, Chi-square=15.191; df=2; P≤0.001); significantly less faculty than students thought that this statement was true (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05; Fig. 9); both 79% of the faculty and 56% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) correctly rejected this statement; note that faculty responses were statistically similar to those by the students from the public institution (sign test two-tail pairwise comparisons, P≥0.05; Fig. 9) but differed from those by the students from the private institution (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05; Fig. 9)

Fig. 9.

Percentage of New England faculty (Fac) versus college students from public secular (Pub), and private secular (Priv) institutions who consider the following statements about evolution to be either true (black bars) or false (white bars): A all current living organisms are descendants of common ancestors, which have evolved for thousands, millions, or billions of years; B humans are apes, relatives of chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans; C the hominid (human lineage) fossil record is so poor that scientists cannot tell with confidence that modern humans evolved from ancestral forms; D the origin of the human mind and consciousness cannot be explained by evolution; and E the universe, our solar system, and planet Earth are finely tuned to embrace human life. Comparisons within groups (asterisks indicate significance): A, Chi-square=4.097; df=2; P=0.129. B, Chi-square=2.623; df=2; P=0.269. C, Chi-square=13.411; df=2; P=0.001. D, Chi-square=14.533; df=2; P≤0.001. E, Chi-square=15.191; df=2; P≤0.001. Lowercase letters indicate sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons within groups, P≤0.05. Fac, n=221; Pub, n=124; and Priv, n=295

Views About Evolution and/or Creation of Humans and Responders’ Religiosity

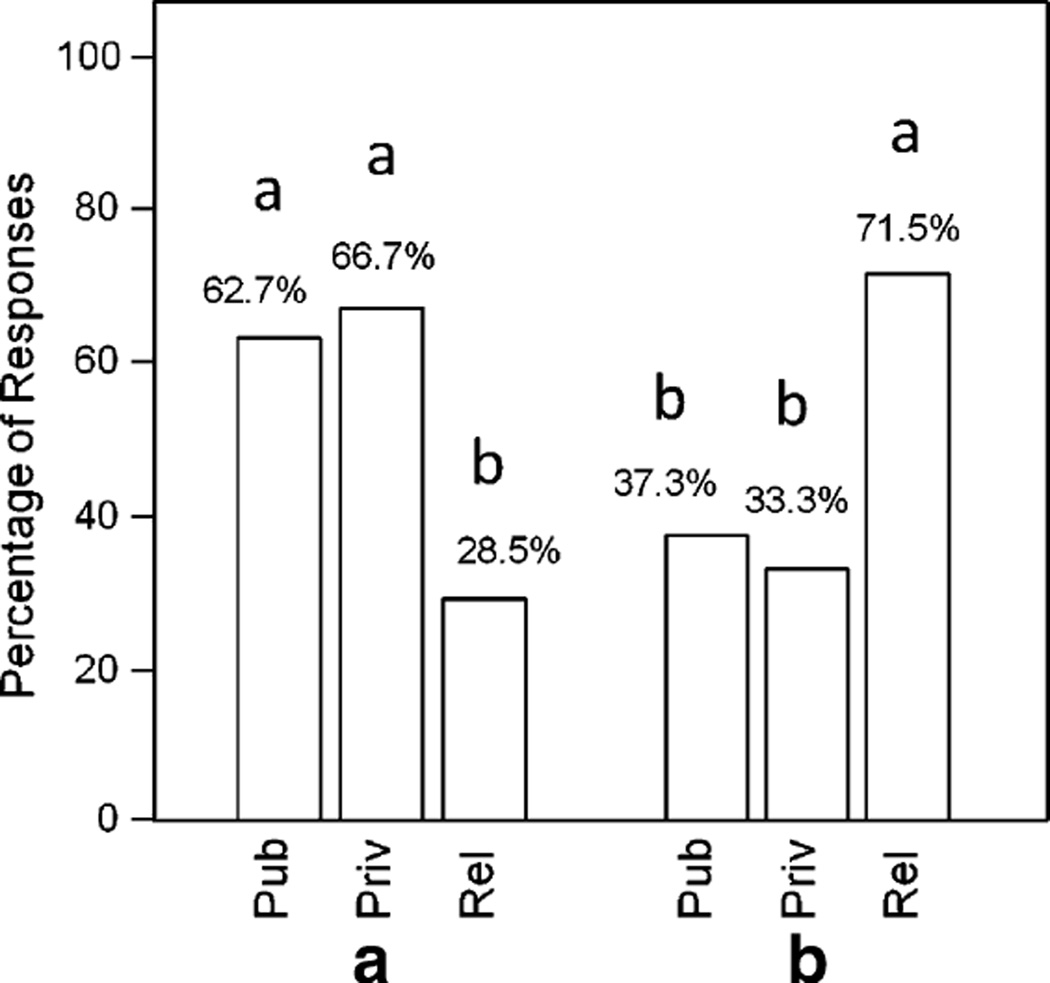

Human Evolution With or Without Creation

Because we could not assess this topic among the faculty (the surveys were not identical in this topic), we show here only the students’ perspectives, which we discuss (see discussion below) in the context of comparisons with relevant literature. Students from public, private, and religious institutions varied in their views about the evolution or creation of humans (Fig. 10; Chi-square=35.006; df=2; P≤0.001): 65% of the students from public and private institutions (mean Pub+ Priv) versus 28.5% of the students from the religious institution thought that humans have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years but God had no part in this process; and 35% of the students from public and private institutions (mean Pub+Priv) versus 71.5% of the students from the religious institution believed that humans have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years but God guided this process. Opinions by the students from the secular public and private institutions were statistically similar (sign test two-tail pairwise comparisons, P≥0.05) but differed from the views by the students from the religious institution (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05).

Fig. 10.

Percentage of New England college students from public secular (Pub), private secular (Priv), and private religious (Rel) institutions who agree with the following statements: A humans have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years but God had no part in this process and B humans have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years but God guided this process. Comparisons between groups: Chi-square=35.006; df=2; P≤0.001; lowercase letters indicate sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05. Pub, n=126; Priv, n=180; Rel, n=165

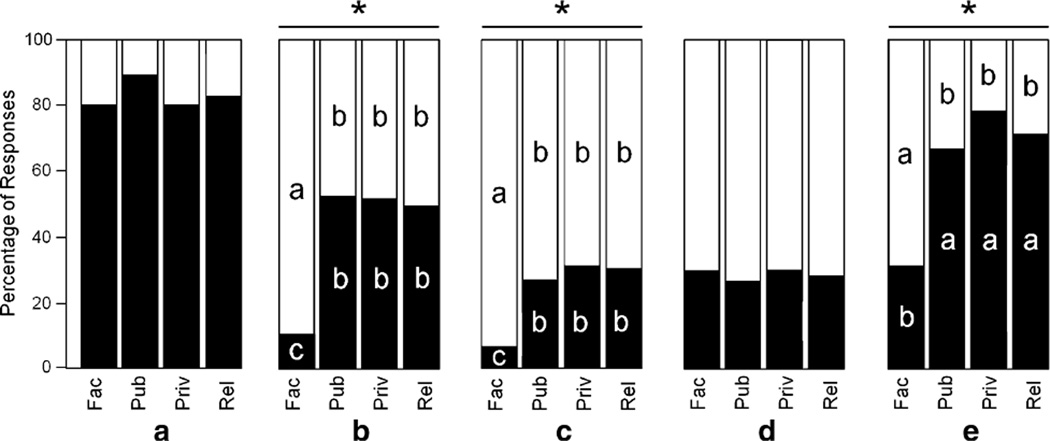

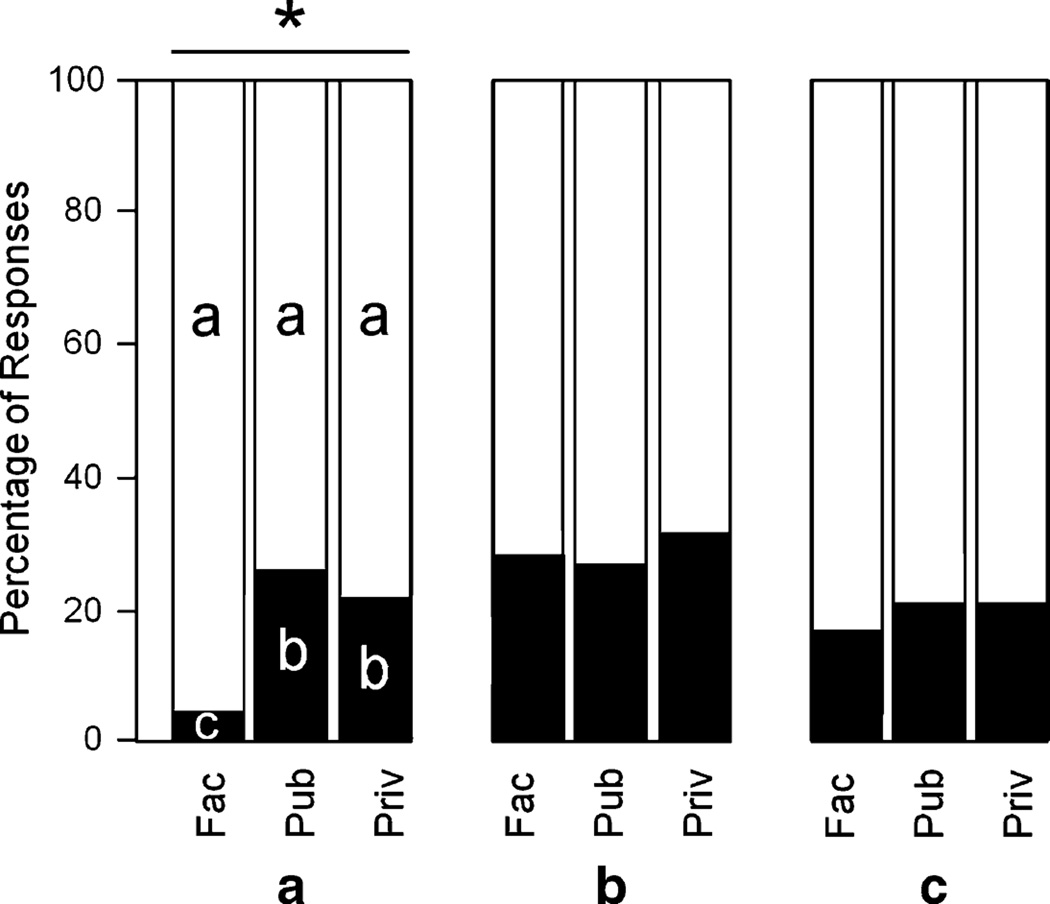

Your Religiosity

Faculty and students varied in their religiosity (Fig. 11); because we could not assess this topic among students from the religious institution (rationale above), here we compare faculty only with students from the public and private institutions: 5% of the faculty and 24% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) considered statement A as true: faith in God is necessary for morality (within group comparisons, Chi-square=17.096; df=2; P≤0.001); significantly less faculty than students thought that this statement was true (sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons, P≤0.05; Fig. 11); 95% of the faculty and 76% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) considered this statement as false, and these responses were statistically similar (sign test two-tail pairwise comparisons, P≥0.05; Fig. 11). Twenty-nine percent of the faculty and 30% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) considered statement B as true: religion is very important in my life; faculty and student responses were statistically similar (within group comparisons, Chi-square=0.611; df=2; P=0.737; Fig. 11); note that 71% of the faculty and 70% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) thought that this statement was false. Seventeen percent of the faculty and 21% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) considered statement C as true: I pray at least once a day; faculty and student responses were statistically similar (within group comparisons, Chi-square= 0.675; df=2; P=0.713; Fig. 11); note that 83% of the faculty and 79% of the students (mean Pub+Priv) thought that this statement was false.

Fig. 11.

Percentage of New England faculty (Fac) versus college students from public secular (Pub), and private secular (Priv) institutions who consider the following statements about religiosity to be either true (black bars) or false (white bars): A faith in God is necessary for morality, B religion is very important in my life, and C I pray at least once a day. Comparisons within groups (asterisks indicate significance): A, Chi-square=17.096; df=2; P≤0.001. B, Chi-square=0.611; df=2; P=0.737. C, Chi-square=0.675; df=2; P=0.713. Lowercase letters indicate sign test two-tail pair-wise comparisons within groups, P≤0.05. Fac, n=221; Pub, n=125; and Priv, n=298

Religiosity, Understanding-of-Science, and Evolution Indexes

The levels of RI, SI, and EI were clearly distinctive for faculty and students:

Religiosity Index

Fac RI=0.50 (n=221), Pub RI=0.74 (n= 123), and Priv RI=0.76 (n=288); note that the disparity between faculty and students relied mainly on choice A of Question 11 (faith in God is necessary for morality) since the partial scores of RI for choices B or C (Fig. 11) were similar: Fac partial scores RI choice A=0.05, choice B= 0.28, choice C=0.17 versus Pub partial scores RI choice A=0.26, choice B=0.28, choice C=0.20 versus Priv partial scores RI choice A=0.22, choice B=0.32, choice C=0.22.

Understanding-of-Science Index

Fac SI=2.27 (n=221), Pub SI=1.62 (n=123), and Priv SI=1.58 (n=288); the disparity between faculty and students was evident in each of the partial scores of SI as follows: for statement scientific theories are based on opinions by scientists the partial scores were Fac SI=0.89, Pub SI = 0.62, and Priv SI = 0.63; for statement scientific arguments are as valid and respectable as their nonscientific counterparts the partial scores were Fac SI=0.57, Pub SI=0.33, and Priv SI=0.33; and for statement crime-scene and accident-scene investigators use a different type of scientific method to investigate a crime or an accident the partial scores were Fac SI=0.81, Pub SI=0.67, and Priv SI=0.62.

Understanding-of-Evolution Index

Fac EI=2.48 (n=221), Pub EI=1.77 (n=123), and Priv EI=1.54 (n=288); the disparity between faculty and students was evident in each of the partial scores of EI as follows: for statement organisms acquire beneficial traits during their lifetimes and then pass on these traits to their descendants the partial scores were Fac EI=0.68, Pub EI=0.33, and Priv EI=0.22; for statement during evolution monkeys such as chimpanzees can turn into humans the partial scores were Fac EI= 0.95, Pub EI=0.72, and Priv EI=0.70; and for statement the origin of the human mind and consciousness cannot be explained by evolution the partial scores were Fac EI=0.85, Pub EI=0.72, and Priv EI=0.62.

Discussion

Below, we round up the values when discussing them in the context of generalizations and remarking on the most relevant patterns:

Views About Evolution, Creationism, and ID

The New England faculty versus students views about evolution, creationism and ID differed distinctly: 96% of the faculty versus 72% of the students supported the exclusive teaching of evolution in science classes, and only 4% of the faculty versus 28% of the students favored equal time to evolution, creationism and intelligent design (Fig. 1); 92% of the faculty versus 52% of the students perceived ID as either not scientific and proposed to counter evolution based on false claims or as religious doctrine consistent with creationism (combined values choices A+B, Fig. 2). Only 8% of the faculty versus 48% of the students had either no opinion about ID, considered it a scientific alternative to evolution and of equal scientific validity among scientists, or thought of ID as a scientific theory about the origin of life on Earth (combined values choices C+D+E; Fig. 2). Although the faculty had clear understanding of ID, the students varied widely in their level of knowledge of ID; only the students from the public institution seemed to be more aware of the nature of ID than their counterparts at the private and religious institutions. We suspect that the particularly strong teaching program in biology and evolution at the public institution (UMassD) might account for this pattern.

Most faculty (97%) and students from the public (87%) and private (82%) institutions preferred factual explanations about the origin of life on Earth and its place in the universe (choice A, Fig. 3), but students from the religious institution were less supportive of this view (68%). Note that students from the public, private and religious institutions were about four, six, and ten times more likely than the faculty (only 3%) to think that evolution and creationism are in harmony, respectively (choice B, Fig. 3). Interestingly, 96% of faculty and students preferred science courses where evolution is discussed comprehensively and humans are part of it (mean combined values choice A, Fig. 4), and 78% of all responders had no problem with either instructors including questions concerning evolution in exams or answering questions concerning evolution (mean combined values choice A, Fig. 5); in fact, one in every five responders considered that science exams should always include some questions concerning evolution (choice B, Fig. 5).

Most faculty (94%) indicated they accept evolution and express it openly regardless of others’ opinions and only 3% admitted to accepting it privately (choices A and C, Fig. 6); in contrast, 64% of the students accepted evolution openly, 22% preferred not to comment on this issue, and 14% admitted to accepting evolution only privately to avoid conflicts with friends and family (mean combined values choices A–C, Fig. 6). Note that 82% of the faculty and 58% of the students thought that evolution is definitely true (mean combined values choice A, Fig. 7).

Although in Questions 1, choice A; 2, choices A+B; 3, choice A; 6, choice A; and 7, choice A (above), the faculty versus student highest rate of responses differed by about 30% (mean of summation highest scores faculty versus students, Figs. 1, 2, 3, 6, and 7), the student responses from the public institution were statistically similar to the faculty in all of these choices (only choice B in Question 2), suggesting more proximity between the views of these two groups than between the faculty and the students from the private and religious institutions. Again, the strong teaching program in biology and evolution at the public institution might account for this pattern (above).

Views About the Evolutionary Process

As we expected, New England faculty showed a better understanding of the evolutionary process than the students; however, both coincided and differed from each other in important ways. For example, 82% (mean value) of faculty and students agreed with a comprehensive definition of evolution as a gradual process by which the universe changes, [which] includes the origin of life, its diversification and the synergistic phenomena resulting from the interaction between life and the environment, and 70% (mean value) correctly rejected the definition that evolution is a random process by which life originates, changes, and ends accidentally in complex organisms such as humans (choices A and D, Fig. 8). Faculty correctly rejected (89%) the notion of “purpose” and “goal toward humanity” in evolution (choice B, Fig. 8), and also the misconception that humans have evolved from chimpanzees (rejection 94%, choice C, Fig. 8) or the possibility of Lamarckian inheritance of acquired traits (rejection only 69%, choice E, Fig. 8). In contrast, the students were not sure if evolution has a purpose or goal, 26% believed that humans come from “monkeys such as chimpanzees,” and 72% were Lamarckian (choices B, C, and E, respectively, Fig. 8). Surprisingly, 30% of the faculty were Lamarckian themselves (choice E, Fig. 8).

The level of understanding of how evolution works varied clearly between faculty and students. Both agreed that evolution relies on common ancestry (92%, mean choice A, Fig. 9) and that humans are apes (72%, mean choice B, Fig. 9); however, one in every four faculty and one in every three students did not know, or accept, that humans are close relatives to chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans (choice B, Fig. 9). Most faculty (96%) but only 80% of the students knew that the hominid fossil record is rich enough for scientists to conclude that humans have evolved from ancestral forms, and 15% of the faculty versus 34% of the students (mean) still believed, incorrectly, that the origin of the human mind cannot be explained by evolution (choices C and D, Fig. 9); indeed, one in every five faculty and almost half of the students (mean) thought, erroneously, that the universe, our solar system and planet Earth are finely tuned to embrace human life (choice E, Fig. 9). The latter is a powerful illusion because the diversity of successful adaptations in nature may give the impression that the environment perfectly matches them; in reality, it is life that “matches” the always changing environments.

Views About Evolution and/or Creation of Humans, and Responders’ Religiosity

Two out of three students from the secular institutions (mean) thought that humans have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years without God’s intervention, but almost three out of four students from the religious institution believed that God guided this process (choices A and B, Fig. 10). We did not assess this topic among the faculty (above) but suspect that professors might show response rates comparable to or even higher than the students from the secular institutions. We base this speculation on the fact that faculty response rate to questions about both acceptance of evolution (Questions 1–7 above) and understanding of the evolutionary process (Questions 8–9 above) were consistently more robust than the students’; moreover, polls report that 87% of members (n=2,533) of the American Association for the Advancement of Science think that humans have evolved without God’s intervention (The Pew Research Center for the People & the Press 2009).

Surprisingly, the rate of agreement with the idea that humans have evolved without God’s intervention was 50% higher among the students from the public and private institutions (mean 65%, choice A, Fig. 10) than among the U.S. high school biology teachers (28%, Berkman et al. 2008), whose views coincide with those of our sample of students from the religious institution (29%). Note that 32/36% of the U.S. general public (n=2,001/1,484; Miller et al. 2006; The Pew Research Center for the People & the Press 2009), 47% of the U.S. high school biology teachers (Berkman et al. 2008), and 72% of our sample of students from the religious institution (choice B, Fig. 10) believe that God guided the process of human evolution.

Interestingly, faculty and students showed a comparable level of religiosity for two of the three questions we asked (choices B, C, Question 11); about 30% considered religion to be very important in their lives and around 20% admitted to praying daily (mean combined values choices B, C, Fig. 11). In contrast, only 5% of the faculty versus 24% of the students believed that faith in God is necessary for morality (choice A, Fig. 11). Note that we did not assess Question 11 among the students from the religious institution, but suspect that their rate of agreement with the choices of this question could have been higher than the faculty’s and the students’ from the secular institutions. We base this speculation on responses to Questions 3 (evolution and creationism are in harmony, choice B, Fig. 3) and 10 (humans have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years but God guided this process, choice B, Fig. 10) where students from the religious institution showed higher response rates than the other groups.

The 30% of New England faculty and students who thought that religion is important in their lives (above) might be comparable to the 33% of American scientists (n= 2,533) who admit to believe in God (The Pew Research Center for the People & the Press 2009), but differs from the 12% of “professional evolutionary scientists” (n=149 members of North American, European, UK, and other countries’ National Academies of Sciences; Graffin and Provine 2007) and 7% of members of the U.S. National Academy of Science (n=260) who believe in a personal God (Larson and Witham 1998). Two recent studies (n=1,646 Ecklund and Scheitle 2007; n=1,417 Gross and Simmons 2009) have also documented that ≈30% of the American professoriat (about 630,000 faculty teaching fulltime at colleges and universities) is religious across institutions and fields, highlighting that researchers in the natural sciences (physics, biology) are less religious than their social sciences counterparts (sociology, economics, history, but except psychology).

Religiosity, Understanding-of-Science and Evolution Indexes

Three factors seem to determine an individual’s acceptance of evolution (Bishop and Anderson 1990; Downie and Barron 2000; Trani 2004; Paz-y-Miño C. and Espinosa 2009a, b, but see Miller et al. 2006; Nadelson and Sinatra 2009): personal religious convictions, understanding the essence of science (method to explore reality) and familiarity with the processes and forces of change in organisms (evolution). Our samples of New England faculty versus students differed clearly in their RI (Fac=0.50, Pub=0.74, Priv=0.76), SI (Fac=2.27, Pub=1.62, Priv=1.58), and EI (Fac=2.48, Pub=1.77, Priv=1.54). In essence, faculty were less religious and more knowledgeable about science and evolution than the students, which might be associated with the higher acceptance of evolution by faculty than by the students (97% versus 78% mean summation choices A and C, Fig. 6, respectively). Numerous studies have found religiosity and belief to be inversely correlated with acceptance of evolution (Miller et al. 2006; The Gallup Poll 2008, 2009; Nadelson and Sinatra 2009) and positively correlated with scientific literacy, particularly genetics (Miller et al. 2006); however, there is discrepancy about the association between general educational attainment and attitudes toward evolution (Miller et al. 2006; Pigliucci 2007; Nehm and Schonfeld 2007). It is important to emphasize that the religiosity indexes of our samples of faculty and students were three and two times below the U.S. national score RI=1.40, n=2,026 (The Pew Global Attitudes Project 2007), respectively, and that the highly educated New England professors had a level of religiosity comparable to that of the general public in Western Europe, the lowest worldwide (The Pew Global Attitudes Project 2007).

Variables Positively and Negatively Associated with Acceptance of Evolution in the U.S

The correlation between education level and attitudes toward evolution has been documented in significant studies: public acceptance of evolution in the U.S. increases from the high school (20/21%), some college (32/41%), college graduate (52/53%) to the post-graduate (65/74%) levels (n=NA/1,018; Brumfiel 2005; The Gallup Poll 2009), reaching the highest score among university professors (97%, this study; choices A+C, Fig. 6). The average acceptance of evolution by the U.S. general public is 35–40% (Brumfiel 2005; Miller et al. 2006), which coincides with the population attaining only some college education (above). Note that only the post-graduate public and highly educated professors of the U.S. have levels of acceptance of evolution comparable to or higher than the general public in other highly industrialized and prosperous nations like Iceland, Denmark, Sweden, France, Japan, and the UK (≈75–85%; Miller et al. 2006).

Negative attitudes toward evolution in the U.S. reside in specific variables: religious beliefs, pro-life beliefs and political ideology account for most of the variance against evolutionary views (total: nine independent variables), which differ distinctly between the U.S. (R2=0.46 total effects) and Europe (R2=0.18 total effects)(Miller et al. 2006; see The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life 2008 for detailed statistics on the relationship between religious affiliations and pro-life beliefs, political ideology and evolution); among U.S. educational professionals, decrease in both evolution acceptance and knowledge correlates with increase in religious commitment (n=337; Nadelson and Sinatra 2009); conservative Republicans in the U.S. accept evolution less than progressive liberals and independents (30% versus 60%, respectively, n=1,007; The Gallup Poll 2007); and frequency of religious practices correlates negatively with acceptance of evolution: 24% among weekly churchgoers versus 71% for seldom or never (n= 1,007; The Gallup Poll 2007).

If attitudes toward evolution by both the general public and highly educated professors correlate, ultimately, with understanding of science/evolution and religiosity/political ideology (positive and negative association of variables, respectively; data above), it follows that robust science education combined with vigorous public debate—where scientific knowledge versus popular belief are constantly discussed—shall increase acceptance of naturalistic rationalism and decrease the negative impact of creationism and ID on “society’s evolution literacy.” But societal interactions between science and ideology are complex, multifactorial, variable in a spatio-temporal context, and subject to public policy, law, and socio-economic change (Lerner 2000; Moore 2002, 2004; Gross et al. 2005; Apple 2008; Berkman and Plutzer 2009; Padian and Matzke 2009; Matzke 2010; Wexler 2010).